Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding

Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step

in Primary Healthcare

Wendy Oude Nijeweme – d’Hollosy

1

, Lex van Velsen

1,2

, Remko Soer

3,4

and Hermie Hermens

1,2

1

University of Twente, MIRA, EWI/BSS Telemedicine, Enschede, The Netherlands

2

Roessingh Research and Development, Telemedicine cluster, Enschede, The Netherlands

3

University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen Spine Center, Groningen, The Netherlands

4

Saxion University of Applied Science, Enschede, The Netherlands

Keywords: Classification of Patients, Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS), Decision Tree, Low Back Pain (LBP),

Ontology, Primary Care, Self-referral, Triage.

Abstract: Low back pain (LBP) is the most common cause for activity limitation and has a tremendous socioeconomic

impact in Western society. In primary care, LBP is commonly treated by general practitioners (GPs) and

physiotherapists. In the Netherlands, patients can opt to see a physiotherapist without referral from their GP

(so called ‘self-referral’). Although self-referral has improved the choice of care for patients, it also requires

that a patient knows exactly how to select the best next step in care for his or her situation, which is not always

evident. This paper describes the design of a web-based clinical decision support system (CDSS) that guides

patients with LBP in making suitable choices on self-referral. We studied literature and guidelines on LBP

and conducted semi-structured interviews with 3 general practitioners and 5 physiotherapists on the

classification of LBP with respect to the best next step in care: visit a GP, visit a physiotherapist or perform

self-care. The interview results were validated by means of an online survey, which resulted in a select group

of key classification factors. Based on the results, we developed an ontology and a decision tree that models

the decision making process of the CDSS.

1 INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common cause for

activity limitation in people, and has a tremendous

socioeconomic impact (Hill, 2011; Ung, 2012). More

than 80% of all persons experience low back pain in

their lifetime (Balagué, 1999). A distinction is made

between specific low back pain and non-specific low

back pain. Most cases of low back pain are non-

specific (Ehrlich, 2003). Non-specific low back pain

is defined as “pain symptoms anywhere in the lower

back between the twelfth rib and the top of the legs,

with no recognizable, specific pathology such as

infection, tumour, osteoporosis, fracture, radicular

syndrome, or cauda equina syndrome that is

attributable to the pain sensations” (Rolli Salathé,

2013).

Most people who suffer from non-specific low

back pain recover within six weeks, but about 10-15%

develop chronic symptoms (Balagué, 1999). It is not

always clear why some people with non-specific low

back pain develop chronic low back pain. In

literature, multiple risk factors have been identified,

including abnormal course of the low back pain,

patients’ belief and expectations about recovery,

anxiety, distress and depression (Weiner, 2010).

Patients with increased risk to develop chronic low

back pain should be identified and supported by the

most relevant healthcare professional at the earliest

possible stage of non-specific low back pain, thereby

reducing the development of a chronic condition

(Childs, 2015), while patients who do not have

increased risk profiles, may do well with self-

management.

In the Netherlands, patients with musculoskeletal

disorders can make use of so-called ‘self-referral’.

Patients’ self-referral, or direct access, means that

patients can be examined, evaluated and/or treated by

a physiotherapist without the requirement of a

physician referral (APTA, 2012; Swinkels, 2014).

Although self-referral has improved the freedom of

Nijeweme-d’Hollosy, W., Velsen, L., Soer, R. and Hermens, H.

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary Healthcare.

DOI: 10.5220/0005662102290239

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 229-239

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

229

choice of care for patients with musculoskeletal

problems, it also requires that a patient knows exactly

what is the best care for his or her situation. This,

however, is not always evident, especially for those

patients that are new to musculoskeletal complaints.

Swinkels et al (2014) showed that people who

directly access the physiotherapist receive less

treatment than patients who are referred by their GP.

Next to this, Bornhöft, Larsson and Thorn (2014)

concluded that patients referred to physiotherapists

required fewer GP visits or received fewer

musculoskeletal disorders-related referrals to

specialists/external examinations, sick-leave

recommendations or prescriptions during the

following year, compared to patients that were

referred to GPs.

Although it may seem that a patient with a

musculoskeletal complaint is served best with referral

to a physiotherapist, there are also situations in which

a patient should go to the GP. Alternatively, it might

also be sufficient to perform self-care. For example,

in case of the presence of so-called ‘Red Flags’,

indicating a serious condition, the patient should

contact his or her GP (Staal, 2013). Therefore, a

correct referral for patients with low back pain is

essential for effective treatment of patients, leading to

fewer instances of chronic low back pain. Moreover,

efficient treatment alleviates the burden on

healthcare. In this paper, we describe a study that

identifies key classification factors to be used as the

basis for the development of a web-based clinical

decision support system (CDSS) that guides patients

with low back pain to the best next step in healthcare

by advising the patient to 1) see a GP, 2) see a

physiotherapist, or 3) perform self-care.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Classification of Patients with Low

Back Pain

In order to enable an appropriate decision for the next

step in the care of low back pain complaints, the

nature of the pain should first be classified correctly

(Hill, 2011) (Koes, 2010). Classifying patients is,

however, a difficult task, due to the high degree of

diversity of patients and risk factors.

Literature on the classification of low back pain is

extensive. This has, for example, resulted in

guidelines for GPs as well as physiotherapists for the

classification and treatment of patients with low back

pain (Chavannes, 2009) (Staal, 2013). In all

guidelines patients are classified and stratified into

groups for further treatment. A recent study showed

that stratified care for back pain implemented in

family practice leads to significant improvements in

patient disability outcomes and a halving in time off

work, without increasing health care costs (Hill,

2011; Foster, 2014).

Basically, literature shows that the classification

of patients with low back pain is mainly based on

looking for the presence of so-called “Red Flags” and

“Yellow Flags”. “Red Flags” are considered to be

serious conditions, such as trauma, cancer, and

herniated discs. “Yellow Flags” are psychosocial

factors complicating the condition as anxiety, distress

and depression. Some papers categorize “Yellow

Flags” into further detail, calling these “Blue Flags”

(factors about work that may lead to prolonged

disability) (Weiner, 2010), “Orange Flags”

(psychiatric factors), and “Black Flags” (contextual

factors as a compensation system under which

workplace injuries are managed) (Nicholas, 2011).

Flags can be used as decisive factors in the

decision process for further referral, also called

‘triage’, to determine whether the patient has to go to

the GP or to the physiotherapist, or can perform self-

care. Furthermore, flags can also be used as decisive

factors at a later stage in the healthcare process, for

example after anamnesis and physical examination of

the patient with low back pain to determine the

treatment path.

2.2 Clinical Decision Support Systems

for Healthcare Professionals as

Well as Patients

Over almost half a century, clinical decision support

system (CDSSs) have been developed to support

healthcare professionals during the clinical decision

process. The term CDSS is defined as “any computer

program designed to help healthcare professionals to

make clinical decisions” (Musen, 2014). One of the

key decision support functions is to provide patient-

specific recommendations that cover assistance in

making a diagnosis, providing advice on therapy, or

both diagnostic assistance and therapy advice

(Perreault, 1999).

CDSSs on the management of low back pain have

also been developed. These CDSSs were mainly

developed to improve uptake of guideline

recommendations on low back pain by healthcare

professionals (Peiris, 2014). Next to this, CDSSs

were developed to assist healthcare professionals in

making a diagnosis on low back pain, like detecting

chronic low back pain by the evaluation of MRI

images of the brain (Ung, 2012), classifying low back

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

230

pain when dealing with uncertainty (Lin, 2006), and

stratifying patients in risk groups on the development

of a chronic condition based on questionnaires

(StarTBack and Örebro) (Hill, 2008)(Linton, 2003).

Besides for supporting healthcare professionals,

systems have also been developed to aid patients in

decision support. These computerized patient

decision aids range from general home healthcare

reference information to symptom management and

diagnostic decision support (Jimison, 2007). For low

back pain, computerized patients decision aids have

been developed for patients facing a surgical

treatment decision (Deyo, 2000)(Knops, 2013). No

systems have been identified in literature that support

patients in the classification of their own low back

pain prior to contacting a primary healthcare

professional. However, such a system will be very

helpful to support patients in the determination of a

correct self-referral, an essential prerequisite for an

effective treatment of patients with low back pain.

3 METHODS

The first steps in the development of a web-based

clinical decision support system that guides low back

pain patients to the most relevant healthcare

professional is finding those factors that can classify

these patients for further referral. To find these

factors, the following steps were taken:

1. Studying physiotherapist and general

practitioner guidelines on the classification and

treatment of patients with low back pain;

2. Performing in-depth, semi-structured interviews

with a group of 3 general practitioners and 5

physiotherapists;

3. Performing a thematic analyses on the interview

transcriptions;

4. Validation of the results gathered thus far by

means of an online survey among the

interviewees.

3.1 Studying Guidelines on Low Back

Pain

During this step, the Dutch physiotherapist guideline

on low back pain (Staal, 2013) and the Dutch GP

guideline on low back pain (Chavannes, 2009) have

been studied. The main goal of this step was to gain a

good understanding of the low back pain domain, the

terminology used in this domain by GPs as well as by

treatment.

3.2 Setting up and Analysis of the

Interviews

Knowledge gained from the previous step was used

to set-up the interviews. These were semi-structured

interviews, based on the following themes:

• Demographics of the interviewee (e.g., age,

specialisation);

• Expertise of the interviewee on classifying and

treating low back pain (e.g., how often the

healthcare professional sees a patient with low

back pain, how knowledge on low back pain is

kept up-to-date);

• Steps in the clinical evaluation and

classification, and management of low back

pain by questioning the healthcare professional

about specific patient cases on self-referral (see

Appendix);

• Definitions on low back pain concepts (e.g., the

differences between specific and nonspecific

low back pain);

• Future expectations of a CDSS that supports

healthcare professionals and patients in the

classification, treatment and management of low

back pain.

The interviews were held among 3 GPs and 5

physiotherapists. Afterwards, the interviews were

transcribed verbatim and analysed by means of

thematic analysis (Braun, 2006).

3.3 Validation of the Identified

Decision Factors for Classifying

Low Back Pain by Means of an

Online Survey

The previous steps resulted into a large number of

decision factors for classifying low back pain related

to further referral in care (GP, physiotherapist, or self-

care). These factors were resubmitted to the

interviewees to be validated by means of an online

survey, and by assessing:

1. The importance of being questioned during

initial triage;

2. The importance to be included into the decision

for further treatment interventions.

4 RESULTS

Studying literature and guidelines resulted in a clear

global overview of possible classes of patients with

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary

Healthcare

231

Figure 1: The knowledge model (ontology) on the classification of patients with low back pain, as deduced from guidelines

on low back pain (Chavannes, 2009) (Staal, 2013).

low back pain, and the possible prognosis and

potential risks these patients face according to these

classes. The focus of the guidelines was mainly

placed on nonspecific low back pain, but factors

related to specific low back pain were also found. We

made a visual overview of the knowledge, gained

during this step. This overview is shown as an

ontology in Figure 1. In Figure 1, the light blocks

refer to knowledge classes that are general to

knowledge concepts in the health care domain, the

dark grey blocks refer to knowledge classes that are

needed to describe the knowledge classes needed to

classify patients with low back pain. This figure also

shows three patient profiles to stratify patients with

non-specific low back pain. Profile 1 is a patient with

non-specific low back pain (no “Red Flags”) with a

normal course. Profile 2 is a patient with non-specific

low back pain with an abnormal course, but no

psychosocial factors (“Yellow Flags”). Profile 3 is a

patient with non-specific low back pain with an

abnormal course and psychosocial factors.

Figure 1 shows that the main determining factors

in classifying patients are the course of the low back

pain (normal, abnormal), the presence or absence of

serious factors (“Red Flags”) as specific underlying

serious conditions, and the presence or absence of

psychosocial factors (“Yellow Flags”). These

observations were also supported by the results of the

interviews. The analysis of the interviews resulted in

43 identified factors for classifying low back pain.

These factors are shown in Table 1.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

232

Table 1: Classification factors for patients with low back

pain, based on literature, guidelines and the interviews.

Divided in the groups ‘general’, ‘psychosomatic’, and

‘serious’.

General factors

Patients’ preference for help

Well-being as experienced by patient

Course of the LBP

Sick leave

Earlier hospitalisation on LBP

Working environment

Family history of LBP

Working ergonomics

Psychosomatic factors (“Yellow Flags”)

Depression

Extremely nervous

Extremely worried

Stress (e.g., caused by family or relational problems)

Relationship with colleagues

Irrational thoughts about LBP

Problems with employers occupational insurance

Dysfunctional cognition

Anxiety disorder

Patients’ coping strategy

An ongoing investigation on personal injury

Kinesiophobia

Personality disorder

Borderline disorder

Serious factors (“Red Flags”)

Start LBP before age of 20

Start LBP after age of 50

Response on analgesics

Prolonged use of corticosteroids

Serious diseases, such as cancer, in patient history

Neurogenic signals

Specific pathologies

Problems with moving, shortly after waking up

Continuous pain, regardless of posture and movement

Decreased mobility

Radiation in the leg below the knee

Nocturnal pain

Rapid weight loss, more than 5 kg per month

Loss of muscle strength

No biomechanical pattern

Trauma

Underlying diseases

Failure symptoms during increased pressure (e.g.,

coughing, straining, lifting gives extra pain)

Possible to walk on the toes and heels?

Incoordination

Stooped posture

The interviewees indicated that in case of the

presence of a serious factor (“Red Flag”), patients

should be sent to a GP. Next, the interviewees

indicated that in case of the presence of a

psychosocial factor (“Yellow Flag”), the patient has a

risk on the development of an abnormal course on low

back pain, possibly resulting in chronic low back

pain. In order to avoid the development of a chronic

condition, these patients should see the right

healthcare professional as early as possible, who can

then guide the patient during his or her rehabilitation

process. In most cases, this will be a physiotherapist,

sometimes working in a multi-disciplinary setting

with other healthcare professionals as, for example, a

psychologist, with the physiotherapist as head

therapist.

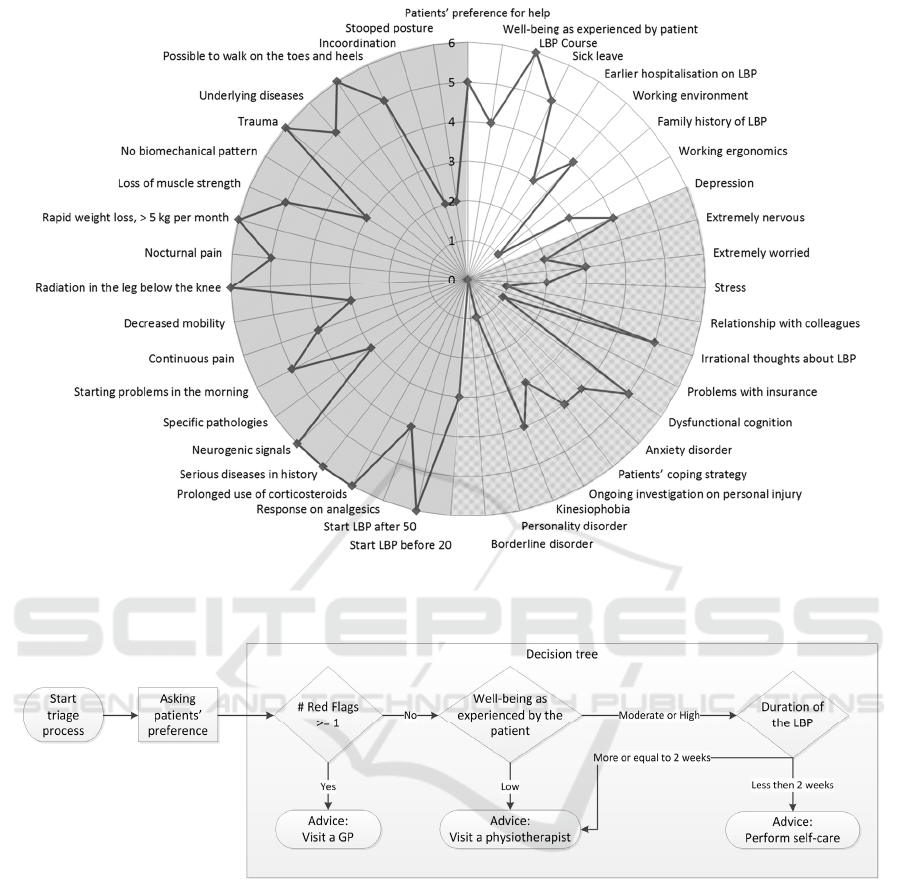

For the CDSS, we want to use the lowest number

of classification factors for providing the best self-

referral advice. This in order to minimize the

workload for the patient in answering questions,

posed by the CDSS. Therefore, we resubmitted the 43

identified classification factors (Table 1) to the

interviewees so that these factors could be validated

on two aspects: 1) their importance during initial

triage to determine a self-referral advice for the

patient, and 2) their importance for the decision

process to determine further treatment interventions,

also after the first anamnesis and physical

examination of the patient with low back pain by the

healthcare professional. Six of the 8 interviewees (3

physiotherapists and 3 GPs) responded on the Internet

survey. This resulted in an overview of the most

important classification factors to determine the

advice for self-referral (Figure 2) and the most

important classification factors for determining a

treatment plan (Figure 3).

Both figures show the results in radar charts. The

identified factors are labelled around the circle. The

number of times an interviewee marked the factor as

important for triage, and for determining a treatment

plan (Figure 2 and Figure 3 respectively), is plotted

for each factor as a point along a separate axis that

starts in the centre of the chart (no interviewee

marked the factor as important) and ends on the outer

ring (all 6 interviewees marked the factor as

important). Connecting these different points results

in a quick overview of the most important factors for

triage and treatment assessment. For better visibility,

we also divided the circle into three pie slices: white

represents the “general factors”, grey checked

represents the “psychosocial factors (Yellow Flags)”,

and dark grey represents the “serious factors (Red

Flags)”.

Figure 2 shows that only general and serious factors

(“Red Flags”) are pointed at the 5th and 6th rings,

fifteen factors in total. Subsequently, we used these

fifteen factors to model the inference process of the

CDSS, presented as a decision tree in Figure 4. This

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary

Healthcare

233

decision tree models the process to determine the

referral advice (see a GP, see a physiotherapist, or

perform self-care). Figure 2 shows twelve serious

factors on the 5th and 6th rings: Start of low back pain

after age of 50, prolonged use of corticosteroids,

serious diseases (e.g., cancer) in patient’s history,

neurogenic signals, continuous pain, regardless of

posture and movement, radiation in the leg below the

knee, nocturnal pain, rapid weight loss (more than 5

kg per month), loss of muscle strength, trauma, and

failure symptoms during increased pressure (e.g.,

coughing, straining, lifting gives extra pain). In

Figure 4, these serious factors are taken together in

one block to keep it as simple as possible: “# Red

flags >= 1” means the presence of one or more serious

factors.

Next, we decided that the factor “Asking patients’

preference” cannot be used in the decision process

itself, because it is no indication of patients’

condition. Therefore, the block “Asking patients’

preference” is not a part of the decision tree.

However, the healthcare professional certainly wants

to know the patient’s preference for help. Therefore

“Asking patients’ preference” is at least part of the

triage process, and will be sent to the healthcare

professional to be used during the first anamnesis,

when the patient is referred to a healthcare

professional.

5 DISCUSSION

By means of studying literature, and interviews and

an online survey among 3 GPs and 5 physiotherapists,

we identified 43 decision factors to classify low back

pain for determining the best next step in primary

healthcare. Fifteen of these identified factors have

been used to model the triage process as the basis in

the design of a web-based clinical decision support

system (CDSS) that supports patients with low back

pain in making a decision on self-referral. That is

advising the patient 1) to see a GP, 2) to see a

physiotherapist, or 3) to perform self-care. A correct

self-referral is an essential prerequisite for an

effective treatment of patients with low back pain.

The identified classification factors correspond to

classifications factors also found in literature

Figure 2: An overview of the identified factors to classify patients with low back pain, and their importance related to initial

triage of patients with low back pain.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

234

Figure 3: An overview of the identified factors to classify patients with low back pain, and their importance to determine

further treatment plans.

Figure 4: The triage process for providing advice on further referral of patients with low back pain.

(Ehrlich, 2003; Koes, 2010; Weiner, 2010; Hill,

2011). In our study, one new identified factor

emerged compared to factors found in literature,

namely the general factor “Patients’ preference for

help” (Table 1). Almost all study participants

indicated the importance of this factor in triage,

because healthcare professionals want to know the

preferences of the patient with respect to the

management of his or her low back pain complaints.

Therefore, although the factor “Patients’ preference

for help” is not an indication of patients’ condition

needed for determining the advice for further referral,

we included this factor into model of the triage

process (Figure 4).

The identified classification factors appear to be

evidence-based, which is supported by the great

overlap between our study results and the factors

found in literature. This means that the identified

factors can be used in the decision process to

determine a self-referral advice for patients suffering

from low back pain. As no other systems have been

found in literature to support patients in the

classification of their own low back pain before

contacting a primary healthcare professional, we

cannot compare our found identified factors to other

similar studies.

Looking at the classification process itself, there

are CDSSs that stratify patients in risk groups on the

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary

Healthcare

235

development of a chronic condition based on

questionnaires as the StarTBack screening tool (Hill,

2008) and the Örebro tool (Linton, 2003). These

CDSSs, however, are intended for use by healthcare

professionals and are not used to triage a patient for

further referral, but for further treatment.

This difference in usage compared to our CDSS

probably also explains the difference in classification

factors used. For example, the StarTBack screening

uses 8 prognostic factors for low back pain: two items

for functioning, and items on radiating leg pain, pain

elsewhere, depression, anxiety, fear avoidance,

catastrophizing, and bothersomeness (Foster, 2014).

These are mainly psychosocial factors, so called

“Yellow Flags”, while the identified factors in our

study for usage during initial triage are only general

and serious factors (“Red Flags”). However, the

results in our study also show the importance of

psychosocial factors (“Yellow Flags”) in the

classification process of patients with low back pain

for assessing further treatment, thus after initial triage

(Figure 3). Here, our study identifies the psychosocial

factors “Irrational thoughts about LBP” and

“Dysfunctional cognition” as most important.

5.1 Study Limitations

In our study, we used the Dutch physiotherapist

guideline on low back pain (Staal, 2013) and the

Dutch GP guideline on low back pain (Chavannes,

2009). This may be considered a limitation of our

study, especially because of the unique situation of

self-referral in the Netherlands. However, Koes et al.

(2010) compared international clinical guidelines for

the management of low back pain. This study showed

that there are some differences between international

guidelines, which may be due to a lack of strong

evidence regarding these topics or due to differences

in local health care systems. But, in general,

diagnostic as well as therapeutic recommendations

are similar among these guidelines. This indicates

that using only Dutch guidelines will not substantially

affect the results as presented in this paper.

Next to this, the interviews and the online survey

were held among a small group of GPs and

physiotherapists. Each interview was transcribed

verbatim and analysed by means of thematic analysis.

After a couple of interviews, no new themes had to be

added meaning data saturation was achieved. A low

variance in the answers on the interview questions

could be expected, because the participants all work

according to the same guidelines. Next to this, all

interviewees were experienced healthcare

professionals on low back pain. That is four of the

five interviewed physiotherapists had also a

background as manual therapist, and all GPs had

more than 10 year experience in primary care.

Because of the achieved data saturation after a few

interviews, but also because interviews are labour-

intensive, the number of interviews was kept low.

5.2 Future Work

In future research we aim to evaluate the process

model, as shown in Figure 4, in more detail. By means

of a vignette survey, also called factorial survey

(Taylor, 2006), we will present cases (vignettes) to a

group of more than 500 GPs and physiotherapists.

This vignette survey will evaluate the importance of

the presence or absence of the 15 classification

factors as identified most relevant for initial triage as

described in this paper. The outcome of the vignette

survey should lead to a smaller set of classification

factors that is an optimum between the factors

necessary to determine a correct referral advice, while

minimizing the workload for patients in answering

questions.

We will relate the remaining factors to questions

to be posed to the patients by the CDSS. For most of

the identified classification factors in our study,

validated questionnaires exist that also can be used in

the CDSS. Commonly used questionnaires in low

back pain research are, for example, the Visual

Analog Scale (VAS) for Pain (Crichton, 2001), and

the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability

Questionnaire (Intensity, 1980).

Based on the results of the vignette survey, and

the usage of validated questionnaires that determine

the presence or absence of a factor, the CDSS will be

developed. Subsequently the CDSS will be evaluated

with patients in primary healthcare.

Figure 5 shows an overview of the intended future

utilization of the CDSS in the further referral of a

patient. The patient answers triage questions posed by

the CDSS. The entered information is used by the

CDSS to advice the patient on the best next step in

healthcare 1. visit a GP, 2. visit a physiotherapist, or

3. perform self-care. The idea is that in all cases the

primary healthcare centre will be notified about the

CDSS advice provided to a patient. When desired by

the primary healthcare centre, an extra check on the

self-care advice is possible, for example, by the

medical assistant. Next to this, the CDSS will check

the self-care process outcome after two weeks. This

is different from the current healthcare process in

which a patient can notify the primary healthcare

centre on his or her self-care progress, but which is

not usually the case when the patient becomes free

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

236

of low back pain.

The CDSS retrieves healthcare information from

the patient. This information can also already be

available within the electronic health record (EHR) of

the patient. Therefore, interoperability between the

CDSS and the healthcare information system is

desired. Advantages of interoperable systems are that

already known information does not need to be

requested from the patient by the CDSS. Next to this,

information retrieved by the CDSS can be stored in

the EHR so that it becomes available to the healthcare

professional, to be used during a consultation with the

patient.

The ontology we developed in our study is the

first step in the realization of interoperable systems,

and this ontology will be further developed during our

CDSS project based on further research findings

during the design process of the CDSS. Knowing the

used knowledge concepts by the CDSS, these can be

related to a terminology system, as SNOMED CT

(SNOMED CT, 2015), that can on its turn serve as an

intermediate terminology system to exchange

information among different healthcare IT systems.

Next to this, we now focussed on low back pain,

because the musculoskeletal disorder domain is a

large domain (Oude Nijeweme - d’Hollosy, 2015). By

using general approaches to design the CDSS, as

building an ontology and a decision tree we expect

these same approaches are also applicable to extend

the CDSS for self-referral advice on other

musculoskeletal disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been conducted within the context of

the eLabEL project. eLabEL is a project of the Centre

for Care Technology Research. eLabEL aims to

contribute to the sustainability of primary care by

developing, implementing and evaluating innovative,

integrated Telemedicine technology by means of a

Living Lab approach.

More information can be found at:

http://www.caretechnologyresearch.nl/elabel.

This work is partly funded by a grant from the

Netherlands Organization for Health Research and

Development (ZonMw); grant number: 10-10400-98-

009.

Figure 5: Overview of the future utilization of the CDSS in the further referral of a patient.

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary

Healthcare

237

We thank the participating healthcare professionals

for their cooperation in our research.

REFERENCES

American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), 2015, A

summary of direct access language in state physical

therapy practice acts, http://www.apta.org/uploadedFi

les/APTAorg/Advocacy/State/Issues/Direct_Access/D

irectAccessbyState.pdf, Sep 9, 2015.

Balagué, F., Troussier, B. and Salminen, J. J., 1999. Non-

specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk

factors. European spine journal, 8(6), 429-438.

Bornhöft, L., Larsson, M. E., and Thorn, J., 2014.

Physiotherapy in Primary Care Triage-the effects on

utilization of medical services at primary health care

clinics by patients and sub-groups of patients with

musculoskeletal disorders: a case-control study.

Physiotherapy theory and practice, 31(1), 45-52.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2),

77-101.

Chavannes, A. W., Mens, J. M. A., Koes, B. W., Lubbers,

W. J., Ostelo, R. W. J. G., Spinnewijn, W. E. M., and

Kolnaar, B. G. M., 2009. NHG-standaard aspecifieke

lagerugpijn. NHG-Standaarden 2009, Bohn Stafleu van

Loghum, 1128-1144.

Childs, J. D., Fritz, J. M., Wu, S. S., Flynn, T. W., Wainner,

R. S., Robertson, E. K., Kim, F. S. and George, S. Z.,

2015. Implications of early and guideline adherent

physical therapy for low back pain on utilization and

costs. BMC health services research, 15(1), 150.

Crichton, N., 2001. Visual analogue scale (VAS). Journal

of Clinical Nursing, 10(5), 706.

Deyo, R. A., Cherkin, D. C., Weinstein, J., Howe, J., Ciol,

M., and Mulley, A. G., 2000. Involving patients in

clinical decisions: impact of an interactive video

program on use of back surgery. Medical care, 38(9),

959-969.

Ehrlich, G. E., 2003. Low back pain. Bulletin of the World

Health Organization, 81(9), 671.

Foster, N. E., Mullis, R., Hill, J. C., Lewis, M., Whitehurst,

D. G. T., Doyle, C., Konstantinou, K., Main, C.,

Somerville, E., Sowden, G., Wathall, S., Young, J., and

Hay, E. M., 2014. Effect of stratified care for low back

pain in family practice (IMPaCT Back): a prospective

population-based sequential comparison. The Annals of

Family Medicine, 12(2), 102-111.

Hill, J. C., Whitehurst, D. G. T., Lewis, M., Bryan, S.,

Dunn, K. M., Foster, N. E., Konstantinou, K., Main, C.

J., Mason, E., Somerville, S., Sowden, G., Vohora, K.

and Hay, E. M., 2011. Comparison of stratified primary

care management for low back pain with current best

practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial.

The Lancet, 378(9802), 1560-1571.

Intensity, P., 1980. Modified Oswestry Low Back Pain

Disability Questionnaire. Physiotherapy, 66, 271-273.

Jimison, H. B., Sher, P. P., and Jimison, J. J., 2007.

Decision Support for Patients, in Berner, E. S. (ed.)

Clinical Decision Support Systems: Theory and

Practice, Springer Science & Business Media, 249-261.

Knops, A. M., Legemate, D. A., Goossens, A., Bossuyt, P.

M. and Ubbink, D. T., 2013. Decision aids for patients

facing a surgical treatment decision: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery, 257(5),

860-866.

Koes, B. W., van Tulder, M., Lin, C. W. C., Macedo, L. G.,

McAuley, J., and Maher, C., 2010. An updated

overview of clinical guidelines for the management of

non-specific low back pain in primary care. European

Spine Journal, 19(12), 2075-2094.

Lin, L., Hu, P. J. H., and Sheng, O. R. L., 2006. A decision

support system for lower back pain diagnosis:

uncertainty management and clinical evaluations.

Decision Support Systems, 42(2), 1152-1169.

Linton, S. J. and Boersma, K., 2003. Early identification of

patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem:

the predictive validity of the Örebro Musculoskeletal

Pain Questionnaire. The Clinical journal of pain, 19(2),

80-86.

Musen, M. A., Middleton, B., and Greenes, R. A. , 2014.

Clinical decision-support systems. In Biomedical

informatics, Springer London, Chapter 20, 643-674.

Nicholas, M. K., Linton, S. J., Watson, P. J. and Main, C.

J., 2011. Early identification and management of

psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients

with low back pain: a reappraisal. Physical therapy,

91(5).

Oude Nijeweme – d’Hollosy, W., van Velsen, L., Swinkels,

I. C. S., and Hermens H., 2015. Clinical Decision

Support Systems for Primary Care: The Identification

of Promising Application areas and an Initial Design of

a CDSS for lower back pain. In Proceedings 17th

International Symposium on Health Information

Management Research (ISHIMR 2015), York, England,

49-59.

Peiris, D., Williams, C., Holbrook, R., Lindner, R., Reeve,

J., Das, A. and Maher, C., 2014. A Web-Based Clinical

Decision Support Tool for Primary Health Care

Management of Back Pain: Development and Mixed

Methods Evaluation, In JMIR research protocols, 3(2).

Perreault, L. E., and Metzger, J. B., 1999. A pragmatic

framework for understanding clinical decision support.

Journal of Healthcare Information Management, 13, 5-

22.

Rolli Salathé, C., and Elfering, A., 2013. A health-and

resource-oriented perspective on NSLBP. ISRN Pain,

vol. 2013, Article ID 640690, 19 pages,

doi:10.1155/2013/640690.

SNOMED CT, The Global Language of Healthcare,

IHTSDO, http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct, Nov 8

2015.

Staal, J. B., Hendriks, E. J. M. , Heijmans, M., Kiers, H.,

Lutgers-Boomsma, A. M. , Rutten, G., van Tulder, M.

W., Den Boer, J., Ostelo, R. and Custers, J. W. H., 2013.

KNGF-richtlijn lage rugpijn, Koninklijk Nederlands

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

238

Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie, De Gans. Amersfoort,

The Netherlands (Dutch).

Swinkels, I. C. S., Kooijman, M. K., Spreeuwenberg, P. M.,

Bossen, D., Leemrijse, C. J., van Dijk, C. E., Verheij,

R., de Bakker, D. H., and Veenhof, C., 2014. An

overview of 5 years of patient self-referral for physical

therapy in the Netherlands. Physical Therapy, 94(12),

1985-1995.

Taylor, B. J., 2006. Factorial surveys: Using vignettes to

study professional judgement. British Journal of Social

Work, 36(7), 1187-1207.

Ung, H., Brown, J. E., Johnson, K. A., Younger, J., Hush,

J. and Mackey, S., 2012. Multivariate classification of

structural MRI data detects chronic low back pain,

Cerebral cortex, bhs378.

Weiner, S. S., and Nordin, M., 2010. Prevention and

management of chronic back pain. Best Practice &

Research Clinical Rheumatology, 24(2), 267-279.

APPENDIX

During the semi-structured interviews, the following

patient cases were presented to the interviewees. For

each case, the interviewee was asked about the

clinical evaluation and classification, management of

low back pain, and the ultimate advice on self-

referral: see a GP, see a physiotherapist, or perform

self-care.

Case 1

• Male, 53 years, bus driver, married;

• Tennis: 2 times a week;

• Since three weeks, he has a burden of the

spine with radiation just above right knee;

• Also low back pain problems in the past;

• Six years ago, some X-rays were made not

showing any causes to explain symptoms;

• On sick leave at the moment;

• Worried that something has been broken in his

back;

• He avoids pain;

• No pain during lying and sitting down.

Case 2

• Female, 69 years old, divorced;

• Low body weight;

• Sleeps poorly;

• Worrying a lot and feeling nervous;

• Has low back pain complaints since several

weeks;

• Continuous pain, independent of posture and

movement;

• Walks crooked.

Case 3

• Male, 39 years, bricklayer;

• Wants to visit primary healthcare for the 2

nd

time in 3 months, because of no improvement

in low back pain complaints despite

medication and advice;

• Otherwise a healthy person;

• No symptoms below the knee;

• Moves slowly, because of pain presence;

• Only walks short distances;

• Believes that low back pain will never end;

• 100% sick leave.

Case 4

• Female, 15 years old, follows 4th grade high

school education;

• Suffers from low back pain since 6 months;

• Unclear start and cause of the low back pain;

• Plays handball;

• Otherwise a healthy person;

• Little pain when lying and sitting;

• Stiffness in the morning.

Design of a Web-based Clinical Decision Support System for Guiding Patients with Low Back Pain to the Best Next Step in Primary

Healthcare

239