On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries

M. S. Goelema

1,2

, M. M. Willems

1

, R. Haakma

2

and P. Markopoulos

1

1

Department of Indutrial Design, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

2

Philips Group Innovation Research, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Keywords: Self-monitoring, Sleep Monitoring, Reactivity, Sleep Diary.

Abstract: The declining costs of wearable sensors have made self-monitoring of sleep related behavior easier for

personal use but also for sleep studies. Several monitor devices come with apps that make use of diary

entries to provide people with an overview of their sleeping habits and give remotely advice. However, it

could be that filling in a sleep diary impacts people’s perception of their sleep or the very behavior that is

being measured. A small-scale field study about the effects of sleep monitoring (keeping a sleep diary) on a

cognitive and a behavioral level is discussed. The method was designed to be as open as possible in order to

focus on the effects of sleep monitoring where participants are not given a goal, motivation or feedback.

Some behavioral modifications were observed, for example, differences in total sleep time and bedtimes

were found (compared to a non-monitoring week and a monitoring week). Nevertheless, what the causes are

of these changes remains unclear, as it turned out that the two actigraph devices used in this study differed

greatly. In addition, some participants became more aware of their sleeping routine, but changing a sleeping

habit was found challenging because of other priorities. It is important to know what the effects may be of

sleep monitoring as the outcomes may already have an effect on the participant behavior which could cause

researchers to work with data that do not represent a real life situation. In addition, the self-monitoring may

serve as an intervention for facilitating healthier sleeping habits.

1 INTRODUCTION

Self-monitoring your sleep is becoming increasingly

accessible to the general public. An already large

number of smartphone applications and dedicated

devices are available on the consumer market that

help track sleep related behavior, (e.g., sleep

duration, waking up during the night, etc.) reflecting

the current trend towards the ‘Quantified Self’ which

seeks to empower individuals to collect information

about themselves, to help them approach health

professionals already informed by an initial analysis,

and to support health interventions with monitoring

their behavior and overall well-being (Swan, 2012).

Actigraphy devices and traditional sleep diaries

are widely used in sleep related research as they are

low cost and allow monitoring sleep behavior in real

life (Carney et al., 2012; Sadeh, 2011). Researchers

have often been concerned with studying

correlations between the two as they provide

subjective and objective measures of sleep quality,

e.g., see (Lockley et al., 1999). However, such

works do not consider the potential effect of self-

monitoring of sleep on a behavioral or cognitive

level. Will people adjust their habits and more

importantly will self-monitoring lead to healthier

habits? Or perhaps it is just knowing that one is

being monitored that makes one feel to adjust his or

her sleeping habits?

Self-monitoring has been researched thoroughly

in the past, especially when it is used as an

intervention, for instance on: weight loss (Butryn et

al., 2007), alcohol consumption (Helzer et al., 2002)

and glucose monitoring (Martin et al., 2006; O’Kane

et al., 2008). However, some of these studies found

an effect of self-monitoring and others did not.

These variations are probably due to methodological

differences or to various levels of subjects’

motivation and predetermined study goals. Still,

self-monitoring on itself could induce adjustments in

behavior. The effect self-monitoring may have on a

cognitive and behavioral level pertains to the

reactivity of self-monitoring. Reactivity is a

phenomenon that emerges when persons alter their

performance or behavior due to the awareness of

being observed (Korotitsch and Nelson-Gray, 1999).

Kazdin (1974) investigated different aspects of self-

240

Goelema, M., Willems, M., Haakma, R. and Markopoulos, P.

On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries.

DOI: 10.5220/0005662602400247

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 240-247

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

monitoring, such as response desirability, goal

setting and feedback upon people’s performance on

a sentence-construction task. It turned out, amongst

others, that:

1) administering a performance goal or

feedback amplified the reactive effects of self-

monitoring,

2) monitoring one’s own behavior or being

monitored by someone else was equally

reactive,

3) the process of self-recording provoked

behavior change independently of observing

the results.

These findings indicate that the very act of self-

monitoring as such may result in reactive behavior.

(As earlier described in Goelema et al. (2014).)

That reactivity is related with self-monitoring has

been shown in the study of Motl et al. (2012). The

purpose of the study was to test a behavioral

intervention for persons with multiple sclerosis

(MS). However, the average steps per day was

higher during the baseline period compared to the

first week of the behavioral intervention. One

possible explanation for this result may be that

during the baseline period the participants wanted to

make as many steps as possible to make a good

impression. This study is a perfect example of the

need to interpret carefully results pertaining to the

potential reactivity of self-monitoring.

As for the traditional way of sleep monitoring,

keeping a diary, there is little known about the

reactivity effects. Bolger et al. (2003) concluded

that there is insufficient evidence that reactivity

forms a threat to diary validity. Litt et al. (1998)

reported that although their participants became

more aware of the monitored behavior, the self-

monitoring was not reactive. Still, this study only

monitored the urge to drink and not assessed a full

diary. Specifically for sleep monitoring, the effects

of keeping a diary have not yet been investigated.

Only a recent study of Todd and Mullan (2014),

reported that keeping a sleep diary (combined with a

response inhibition intervention) made people avoid

anxiety and stress-provoking activities before going

to bed. However, since the study of Todd and

Mullan includes an intervention, any effects on

behavior may not be attributed to the self-monitoring

per se. Nevertheless, cognitive behavioral therapy is

often supported by keeping a diary and thereby

shaping awareness (Okajima et al., 2011).

We performed a first study (briefly reported in

Goelema et al. (2014)), expecting that tracking

behavior with actigraphy would impact sleep related

behavior. This was not confirmed, and as it turned

out it was the act of keeping a diary that seemed to

impact on the cognitive level though less on a

behavioral level. This finding prompted the current

study where we investigated the effects of keeping a

sleep diary. The set-up of study 1 was reverted for

this study. During the whole three weeks

participants wore an actigraphy device and filled out

only in the second week a sleep diary. We

hypothesized that between the first week of non-

filling out a diary and the week of keeping a diary

the sleep efficiency (SE) and total sleep time (TST)

increases and wake time after sleep onset (WASO)

and bedtime (BT) decreases in the second week.

Secondly, we hypothesized that when comparing

week 2 with week 3 the results would be the reverse,

namely a decrease of SE and TST and increase of

WASO and BT.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

To safeguard the reliability of our results, we

decided to recruit participants aged between 40 and

60 years old. The reason for choosing this age range

was that Monk et al. (2003) found a significant

association between lifestyle regularity and good

sleep. Moreover, previous research has shown

irregular sleep quality and rhythm amongst school-

aged children, youngsters, and adolescents (Dahl

and Lewin, 2002; Monk et al., 1994; Sadeh et al.,

2000). To assess whether completing a sleep diary

affects people’s lives, a population is needed that

normally would show regular sleeping times.

Considering this, the target group was set to age 40-

60, assuming that people around this age have the

most stable daily routine and sleep rhythm.

Because of practical constraints relating to the

availability of devices, two groups of 10 subjects

were made, originally resulting in 20 participants for

this study. Participants wore a different device in

each group (see heading measures) and one group

started two weeks later. The process of recruitment

was the same for each group. The intended fifteen

nights of data per participant (total of 300 data

records as opposed to the eventual 203 records) was

reduced greatly because of several circumstances.

These circumstances included failure of data

recording from the devices, failure of setting ‘In and

Out Bed Times’ (software related issues), failure of

following instructions by participants and the

irregularities in the sleep pattern of participants

(emergencies, illness, parties, deadlines, that have

On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries

241

led to exceptional bed times). The loss of data ruled

out five participants, eventually resulting in a total of

15 participants for this study.

2.2 Measures

Participants were asked to fill in the Pittsburg Sleep

Quality Index (Buysse et al., 1989) to determine

their normal sleeping behavior. The PSQI contains

19 self-rated questions, which are combined to form

seven ‘component’ scores, each ranging from 0-3

points (‘0’ indicating no difficulty and ‘3’ indicating

severe difficulty). The seven component scores

together form a ‘global’ score, ranging from 0-21

points, ‘0’ indicating no difficulty and ‘21’

indicating severe difficulties in all areas.

The ‘Consensus Sleep Diary’ (CSD) was used

only in the second week, which contains questions

about initiating and maintaining sleep as well as a

global appreciation of sleep (Table 1) (Carney et al.,

2012) Sleep diaries are effective tools to get an

insight in participants’ sleeping behaviour and

discover changes in sleeping patterns.

Table 1: Consensus Sleep Diary – Core.

Consensus Sleep Diary – Core

1. What time did you get into bed?

2. What time did you try to go to sleep?

3. How long did it take you to fall asleep?

4. How many times did you wake up, not

counting your final awakening?

5. In total, how long did these awakenings

last?

6. What time was your final awakening?

7. What time did you get out of bed for the

day?

8. How would you rate the quality of your

sleep? (Very poor, poor, fair, good,

very good)

At the end of the study, a short interview was held

with each participant. Amongst others they were

asked if and how the CSD influenced their

behaviour. Did they go to bed and get up earlier or

later because of the diary? Did they change any

rituals and were they more aware of the hours of

sleep they should be getting? Furthermore they were

asked about their sleep experience during the whole

period of the study, and more specifically whether

they slept better or worse comparing the different

phases of the study. In addition, questions regarding

the effect of wearing an actigraphy device during

sleep were also assessed. The closing interview also

took care of certain irregularities that might have

occurred in the data (e.g., occasions that might have

disturbed a good night’s sleep, or events that

required the participant to go to bed much later or

get up much earlier than regularly). Lastly, during

the closing interview we revealed to them the actual

goal of the study (investigating the reactivity effects

of a sleep diary).

Participants in Group 1 (participants 101-107)

were given the Philips Actiwatch Spectrum (Philips

Respironics, Inc, Murrysville, USA), while

participants in Group 2 (participants 108-115) were

given the ActiGraph device (ActiGraph GT3X,

LLC, Pensacola, FL). Both devices make use of a

accelerometer to detect and log wrist movement,

also known as actigraphy. The Actiwatch Spectrum

contains a piezoelectric accelerometer with a

sensitivity of 0.025g. The hardware of the Actigraph

consists of a triaxial accelerometer with a sensitivity

of 0.05 g. They were set to a standard data sampling

rate of 120 per hr (every 30 seconds), providing

ample data per night. In addition, both devices have

an ambient light sensor but these outcomes were not

used in this study.

2.3 Procedure

The participants were instructed to wear an

actigraphy device on their non-dominant hand from

Sunday-Monday night to Thursday-Friday night for

3 weeks straight, excluding the weekends and

including the wake-up-times on working days.

Participants were asked to fill out the CSD each

morning, only during the second week.

Many actigraphy sleep–wake scoring algorithms

rely on sleep diary information to set scoring periods

for sleep onset and offset. In this study, participants

were instructed to start wearing their device when

they were trying to fall asleep. In case of going to

bed earlier to read a book, watch television, etc. they

were told not to wear the actigraphy device until

they actually wanted to go to sleep and then to put it

on the wrist. Furthermore they were instructed to

take off the actigraphy device right after their final

awakening. For the Actiwatch the same procedure

was applied, only the function of the marker button

to indicate that someone wanted to fall asleep was

explained extra, but eventually barely used by the

participants.

2.4 Data Analysis

‘In Bed’ and ‘Out of Bed’ times were determined by

analyzing the beginning and endings of the activity

graphs. One participant reported to have forgotten to

take the ActiGraph off. This omission and other

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

242

mistakes were corrected by using the ‘In Bed’ and

‘Out of Bed’ times indicated in the diaries. In case of

unreliable indications, data was removed from the

calculations. The sleep efficiency was calculated as

ratio of the total minutes of sleep time (TST) divided

by the total minutes of time in bed (TTB).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

IBM 20. New variables were computed to extract the

mean of the SE, WASO, TST and BT of each week

to take care of missing values. Repeated measure

analysis was conducted, with time (the phases of the

experimental study) as the within subject factor. The

contrast repeated was used, to compare week 1 with

week 2 and week 2 with week 3. The assumption of

sphericity was met, meaning that the level of

dependence between experimental conditions was

roughly equal. However, the assumption of

normality was not met and therefore the outcome of

the Greenhouse-Geisser test was used. The repeated

measures analyses were done for each parameter

(SE, TST, WASO and BT), and for the complete

group. First, we looked at whether there was a main

effect for time and if so, then pairwise comparisons

were examined. For each group separately paired-

sample t-test or Wilcoxon signed ranked test was

conducted. Statistical significance was set at p

<0.05.

3 RESULTS

The characteristics of the sample are listed in Table

2. The average age of the sample was just under 52

years and 10 out of 15 were women. For group 1, the

average amount of sleep time was 5.89 hours (SD

=0.9 hours) and for group 2 it was 6.55 hours (SD =

0.82 hours). The average PSQI score was a little

above the cut-off score of 5, this would indicate that

the participants experienced slight sleeping

problems.

Table 2: Demographic data and sleep characteristics of the

samples.

Group 1

(N = 7)

Group 2

(N = 8)

A

g

e 51.14 (5.8) 50.9 (3.9)

Gender ♂ 5 5

Bedtime 24:05:49 (41:13) 23:25:29 (36:51)

TST 353.23 (54.3) 393 (48.9)

WASO 58.11 (23.2) 36.9 (20.6)

SE % 81.5 (6.4) 91.3 (4.7)

PSQI 6 (2.5) 5.7 (2.4)

Note. Values are mean (standard deviations) or percentage of cases.

Bedtime = (hh:mm:ss)/ (mm:ss)TST = total sleep time (min), WASO =

Wake time after sleep onset (min), SE = Sleep efficiency and PSQI =

Pittsburgh sleep quality index.

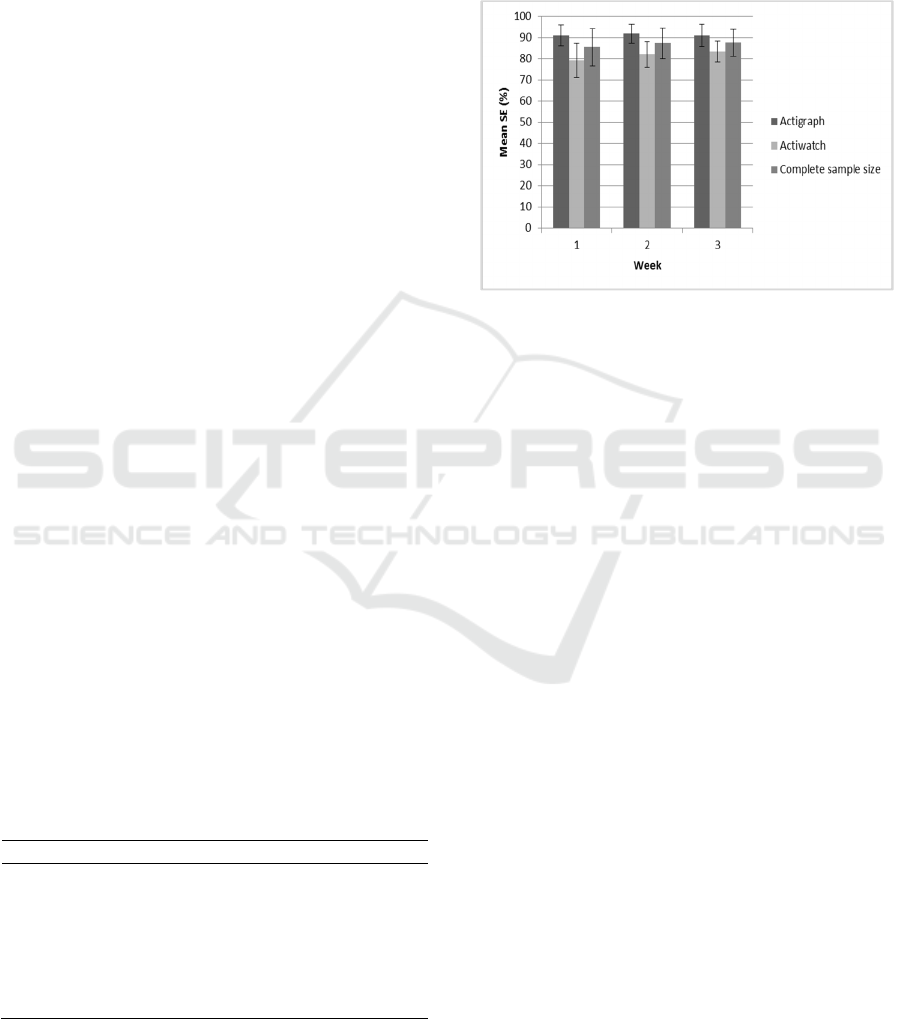

First all data from both groups were analysed

using the mean value for each week per participant.

For the complete group no significant results were

found, between baseline and week 2 or week 2 and

week 3 (for example: SE, mean week 1 = 85%,

mean week 2 = 87%; df = 2, F = 2.54, p = .097,

Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mean sleep efficiency (SE) for each week,

displayed for each group separately and for the whole

sample, including error bars (1 +- SD).

When testing the hypotheses for only the

participants who wore the Actiwatch no significant

results were found for SE and WASO. There was a

significant difference between baseline and week 2

for TST (Z = -2.197, p = .028; mean TST: week 1 =

328, week 2 = 361, Figure 2). This means that

during the week of filling out the sleep diary the

total sleep time was longer than during baseline.

Moreover, a difference in mean bedtimes was

observed between week 2 and week 3 (Z = -2.366, p

= .018; mean BT: week 2 = 24:09:14 week 3 =

23:47:27, Figure 3). This indicates that in the last

week of the study participants went to bed earlier

than during week 2.

For the ActiGraph group no significant results

were observed between baseline and week 2 or week

2 and week (For example: WASO, Z = -,98, p =

.327; mean week 2 = 35,74, mean week 3 = 36,91,

Figure 4).

3.1 Closing Interview

The closing interview revealed that it was difficult

for the participants to notice any difference in sleep

quality on a weekly basis. The participants did not

change their sleep routine based on filling the

diaries. They did not go to bed earlier or changed

their alarm clock settings. However, a handful of

participants indicated that filling in the diary made

them more aware of their sleeping habits.

On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries

243

Figure 2: Mean total sleep time for each week, displayed

for each group separately and for the whole sample,

including error bars (1 +- SD).

Figure 3: Mean bedtimes for each week, displayed for

each group separately and for the whole sample, including

error bars (1 +- SD).

Figure 4: Mean wake time after sleep onset (WASO) for

each week, displayed for each group separately and for the

whole sample, including error bars (1 +- SD).

Five participants reported that they did have to

get used to the actigraphy devices during the first

few days of the experiment. They indicated that this

might have had a minor influence when falling a

sleep the first few days. Except for one participant

who reported very bad sleep during phase 2,

according to that subject of wearing the actigraphy

device. What did become apparent was that as the

study evolved wearing the actigraphy devices

became an automated process of which the

participants were less aware than in the beginning.

4 DISCUSSION

A significant effect was found when comparing TST

of week 1 with week 2 and between bedtimes of

week 2 and week 3 of the Actiwatch group. The

increase of the TST was expected while the decrease

of bedtimes in week 3 was not anticipated, as we had

expected the opposite effect. It could be that the

decrease in bedtimes in week 3 is caused by keeping

the diary which may have had longer lasting effects

(the week after). No significant results were found

with the overall group or the Actigraph device.

Because of trends seen in the graphs, we also

compared the baseline with week 3, and found

significant effects between total sleep time and

bedtimes in the Actiwatch group, however, what the

cause of these effects could be remains unclear.

Participants indicated during the closing interview,

that they experienced worse sleep only in the first

one or two nights of the study, because they had to

get used to the actigraphy device and the general

idea of participating in a sleep related study.

Moreover, no differences were found in the

outcomes between good and bad sleepers based on

PSQI scores (≤ 5 is considered as good).

In this study important differences were found

between the results of the Actigraph and the

Actiwatch devices. The reliability and validation of

actigraphy is a much discussed topic and it may have

played a role in this outcome. Related reports

support the validity of data recording with the

Philips Actiwatch (Gironda et al., 2007; Hyde et al.,

2007; Weiss et al., 2010), whereas the Actigraph

seems to be less reliable (Hjorth et al., 2012). The

golden standard for sleep studies is considered to be

polysomnography (PSG). Although actigraphy and

PSG tend to correspond reasonably well (Ancoli-

Israel et al., 2003; Tryon, 2004), research reports

measurements errors in actigraphy (Blackwell et al.,

2008). The accuracy of the Actiwatch and Actigraph

is respectively 86.3% (measured in young and older

adults, healthy or chronic primary insomniac and 23

night-workers) and 82.8% (based on naps in healthy

young adults) (Cellini et al., 2013; Marino et al.,

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

244

2013). This discrepancy in accuracy and especially

taking into account the study samples may be a

reason why we found these differences between the

devices. (We found significant differences between

the Actiwatch group and the Actigraph group, for

instance, mean TST week 1, Z = -2.32 p < .021.) In

addition, the differences in accuracy could be due to

different sensor sensitivity, a different way to

calculate activity counts and each have their own

algorithm for sleep/wake detection. As a result,

conclusions based on the objective measures

(actigraphy) of this data set could not be made.

However, due to different populations in the groups,

the differences we found could also have been a

result of between subject variation.

Based on the closing interview, participants

mentioned they did not change any sleeping habits,

but some of them were more aware of their sleeping

routines because of filling in the sleep diary. This

confirms the findings by Goelema et al. (2014)),

where some participants did change or tried to

change their pre-bedtime rituals, probably caused by

filling in the sleep diary. These studies suggest that

presumably motivation or a significant alteration in

the daily routine of a person is a necessary

prerequisite for influencing sleeping behaviour

through self-monitoring.

A remarkable side-note on the failure of

following instructions by participants, is that during

the diary week, hardly any missing data was

recorded while in week 1 and week 3 there was

considerably more missing data. This confirms

earlier investigations on wrist actigraphy adherence

research by Carney et al. (2004), who suggests that

combining actigraphy monitoring with diaries can

increase the likelihood of adherence to sleep

instructions.

The behavior of sleep is deeply rooted in one's

daily routine and modifying this behavior will have

a large impact on the rest of the daily rhythm. Vice

versa, ‘other factors’ influence sleeping behavior

greatly. This means that probably one needs to be

motivated to actually adjust a sleep behavior. When

participants are motivated for adjusting a behavior,

in the majority of studies, significant results have

been found, at least for the short-term (Bouffard-

Bouchard et al., 1991; Zimmerman and Kitsantas,

1999). Although these studies were all conducted on

different topics, such as improving learning skills

than on changing sleeping habits, there is a high

likelihood that the same will be true for adjusting a

sleeping behavior or thought. This would mean for

sleep monitoring, that when individuals are

motivated they are more eager to adjust their

sleeping behavior and this could lead to alterations

in the daily routine of that person. Moreover, it will

increase the level of self-control and could

contribute to a healthier lifestyle, as it becomes more

known that sleeping well is essential for health,

psychological well-being and daytime functioning

(Totterdell et al., 1994).

The importance of motivation for self-monitoring

can be integrated into a theory of self-regulation,

however several versions of the self-regulation

theory are proposed (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein, 1979).

Schunk and Zimmerman (2008) argue that

motivation is an essential dimension of self-

regulation learning, while other theories put more

emphasis on the self-efficacy beliefs and

discrepancy in costs and benefit it may have on the

short or long term.

In addition, this motivation may be affected by

the feedback a monitoring device gives. When the

insight into a certain behavior increases, this will

make a person more aware of their behavior and

therefore the feedback could turn into an agreeable

argument to get motivated to adjust that behavior. If

feedback could have been given immediately then

the outcome might have been different, as has been

found in several other studies (Gajar et al., 1984;

Kazdin, 1974). Most consumer-level devices

available in the market supply feedback to their

users, giving users a great insight in their monitored

behavior. Moreover, persons are encouraged to set

personal goals, to acquire a healthier lifestyle. For

persons with already a high desire of self-control

this would serve as a handle to gain control of one’s

life.

This study is the first study that makes an

attempt to explore the reactivity of sleep measures in

a quantitative way. The effect size found of the

significant result between TST 1 and TST 2 for the

Actiwatch group was medium: .587. However,

whether this effect size is significant for clinical

purposes remains unknown. On average a person

sleeps between 7 and 8 hours, but what the

acceptable deviation from 7 a 8 hours is, is not

known. There is no clear clinically relevant effect

size within the sleep field operationalized.

Moreover, an individual situation is probably more

important for disparity in total sleep time, as sleep is

very interlinked with the daily routine it can have a

significant effect for one individual and not for

another individual.

As mentioned in the method section, there was a

difference in the expected 300 data records and the

eventual 203 data records, because of unforeseen

circumstances. The loss of data should be accounted

On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries

245

for and possibly be prevented. Future research, could

attempt to replicate these results during a longer

study. To adjust behavior, and especially (sleep)

behavior that is incorporated in the daily routine, it

probably takes more time to adjust. In addition, a

cross-over design or adding a control group that is

not subjected to a diary is another way to control and

justify temporal effects. Moreover, a distinction

between persons who already want to improve their

sleep and those who are just curious about their

sleep should be made. This will give an insight into

the motivation level of a participant before starting

with the study, which is an important factor on their

thoughts and behavior. Lastly, the influence of

feedback should also be accounted for by the study

method, to find out what the effects are of feedback

on sleep monitoring.

To conclude, objective behavioral changes were

observed in the Actiwach group whether this is due

to the device that was used or a real behavior change

remains inconclusive. Nevertheless, higher

awareness due to filling in the diary was observed in

both of our studies. It is important to know what the

effects can be when self-monitoring your sleep, as

the prospect is that monitoring physiological

features will become more and more normal and

more advanced devices will be available. This can

lead to more awareness of the behavior that is being

monitored. Moreover, the effects of sleep

monitoring need to be taken into consideration when

someone is coached remotely, as data that is

presented may not represent real life information.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., 1991. The theory of planned behavior.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, Theories of Cognitive Self-Regulation 50,

179–211.

Ancoli-Israel, S., Cole, R., Alessi, C., Chambers, M.,

Moorcroft, W., Pollak, C., 2003. The role of

actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms.

Sleep 26, 342–392.

Blackwell, T., Redline, S., Ancoli-Israel, S., Schneider,

J.L., Surovec, S., Johnson, N.L., Cauley, J.A., Stone,

K.L., 2008. Comparison of Sleep Parameters from

Actigraphy and Polysomnography in Older Women:

The SOF Study. Sleep 31, 283–291.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., Rafaeli, E., 2003. Diary Methods:

Capturing Life as it is Lived. Annual Review of

Psychology 54, 579–616.

Bouffard-Bouchard, T., Parent, S., Larivee, S., 1991.

Influence of Self-Efficacy on Self-Regulation and

Performance among Junior and Senior High-School

Age Students. International Journal of Behavioral

Development 14, 153–164.

Butryn, M.L., Phelan, S., Hill, J.O., Wing, R.R., 2007.

Consistent Self-monitoring of Weight: A Key

Component of Successful Weight Loss Maintenance.

Obesity 15, 3091–3096.

Buysse, D.J., Reynolds III, C.F., Monk, T.H., Berman,

S.R., Kupfer, D.J., 1989. The Pittsburgh sleep quality

index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and

research. Psychiatry Research 28, 193–213.

Carney, C.E., Buysse, D.J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger,

J.D., Krystal, A.D., Lichstein, K.L., Morin, C.M.,

2012. The Consensus Sleep Diary: Standardizing

Prospective Sleep Self-Monitoring. Sleep 35, 287–

302.

Carney, C.E., Lajos, L.E., Waters, W.F., 2004. Wrist

Actigraph Versus Self-Report in Normal Sleepers:

Sleep Schedule Adherence and Self-Report Validity.

Behavioral Sleep Medicine 2, 134–143.

Cellini, N., Buman, M.P., McDevitt, E.A., Ricker, A.A.,

Mednick, S.C., 2013. Direct comparison of two

actigraphy devices with polysomnographically

recorded naps in healthy young adults. Chronobiology

International 30, 691–698.

Dahl, R.E., Lewin, D.S., 2002. Pathways to adolescent

health sleep regulation and behavior. Journal of

Adolescent Health 31, 175–184.

Fishbein, M., 1979. A theory of reasoned action: Some

applications and implications. Nebraska Symposium

on Motivation 27, 65–116.

Gajar, A., Schloss, P.J., Schloss, C.N., Thompson, C.K.,

1984. Effects of Feedback and Self-Monitoring on

Head Trauma Youths’ Conversation Skills. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis 17, 353–358.

Gironda, R.J., Lloyd, J., Clark, M.E., Walker, R.L., 2007.

Preliminary evaluation of reliability and criterion

validity of Actiwatch-Score. Journal of Rehabilitation

Research and Development 44, 223.

Goelema, M.S., Haakma, R., Markopoulos, P., 2014. Does

being monitored during sleep affect people on a

cognitive and behavioral level? Presented at the 7th

International Conference on Health Informatics (ICHI

’14), Angers, 27–33.

Helzer, J.E., Badger, G.J., Rose, G.L., Mongeon, J.A.,

Searles, J.S., 2002. Decline in Alcohol Consumption

during Two Years of Daily Reporting. Journal of

Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 63, 551-558.

Hjorth, M.F., Chaput, J.-P., Damsgaard, C.T., Dalskov, S.-

M., Michaelsen, K.F., Tetens, I., Sjödin, A., 2012.

Measure of sleep and physical activity by a single

accelerometer: Can a waist-worn Actigraph adequately

measure sleep in children? Sleep and Biological

Rhythms 10, 328–335.

Hyde, M., O’driscoll, D.M., Binette, S., Galang, C., Tan,

S.K., Verginis, N., Davey, M.J., Horne, R.S.C., 2007.

Validation of actigraphy for determining sleep and

wake in children with sleep disordered breathing.

Journal of Sleep Research 16, 213–216.

Kazdin, A.E., 1974. Reactive self-monitoring: The effects

of response desirability, goal setting, and feedback.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

246

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42,

704–716.

Korotitsch, W.J., Nelson-Gray, R.O., 1999. An overview

of self-monitoring research in assessment and

treatment. Psychological Assessment 11, 415–425.

Litt, M.D., Cooney, N.L., Morse, P., 1998. Ecological

momentary assessment (EMA) with treated alcoholics:

Methodological problems and potential solutions.

Health Psychology 17, 48–52.

Lockley, S.W., Skene, D.J., Arendt, J., 1999. Comparison

between subjective and actigraphic measurement of

sleep and sleep rhythms. Journal of Sleep Research 8,

175–183.

Marino, M., Li, Y., Rueschman, M.N., Winkelman, J.W.,

Ellenbogen, J.M., Solet, J.M., Dulin, H., Berkman,

L.F., Buxton, O.M., 2013. Measuring Sleep:

Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Specificity of Wrist

Actigraphy Compared to Polysomnography. Sleep 36,

1747–1755.

Martin, S., Schneider, B., Heinemann, L., Lodwig, V.,

Kurth, H.-J., Kolb, H., Scherbaum, W.A., 2006. Self-

monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes and

long-term outcome: an epidemiological cohort study.

Diabetologia 49, 271–278.

Monk, T.H., Petrie, S.R., Hayes, A.J., Kupfer, D.J., 1994.

Regularity of daily life in relation to personality, age,

gender, sleep quality and circadian rhythms. Journal

of Sleep Research 3, 196–205.

Monk, T.H., Reynolds, C.F., Buysse, D.J. DeGrazia, J.M.,

Kupfer, D.J., 2003. The Relationship Between

Lifestyle Regularity and Subjective Sleep Quality.

Chronobiology International 20, 97–107

Motl, R.W., McAuley, E., Dlugonski, D., 2012. Reactivity

in baseline accelerometer data from a physical activity

behavioral intervention. Health Psychology 31, 172–

175.

Okajima, I., Komada, Y., Inoue, Y., 2011. A meta-analysis

on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral

therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep and Biological

Rhythms 9, 24–34.

O’Kane, M.J., Bunting, B., Copeland, M., Coates, V.E.,

Gulliford, 2008. Efficacy of Self Monitoring of Blood

Glucose in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Type 2

Diabetes (ESMON Study): Randomised Controlled

Trial. British Medical Journal 336, 1174–1177.

Sadeh, A., 2011. The role and validity of actigraphy in

sleep medicine: An update. Sleep Medicine Reviews

15, 259–267.

Sadeh, A., Raviv, A., Gruber, R., 2000. Sleep patterns and

sleep disruptions in school-age children.

Developmental Psychology 36, 291–301.

Schunk, D.H., Zimmerman, B.J., 2008. Motivation and

Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and

Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New

York, NY.

Swan, M., 2012. Sensor Mania! The Internet of Things,

Wearable Computing, Objective Metrics, and the

Quantified Self 2.0. Journal of Sensor and Actuator

Networks 1, 217–253.

Todd, J., Mullan, B., 2014. The Role of Self-Monitoring

and Response Inhibition in Improving Sleep

Behaviours. Int.J. Behav. Med. 21, 470–477.

Totterdell, P., Reynolds, S., Parkinson, B., Briner, R.B.,

1994. Associations of sleep with everyday mood,

minor symptoms and social interaction experience.

Journal of Sleep Research & Sleep Medicine 17, 466–

475.

Tryon, W.W., 2004. Issues of validity in actigraphic sleep

assessment. SLEEP 27, 158–165.

Weiss, A.R., Johnson, N.L., Berger, N.A., Redline, S.,

2010. Validity of Activity-Based Devices to Estimate

Sleep. J Clin Sleep Med 6, 336–342.

Zimmerman, B.J., Kitsantas, A., 1999. Acquiring writing

revision skill: Shifting from process to outcome self-

regulatory goals. Journal of Educational Psychology

91, 241–250.

On the Reactivity of Sleep Monitoring with Diaries

247