Can a Wii Bowling Tournament Improve Older Adults’ Attitudes

towards Digital Games?

Fan Zhang, Simone Hausknecht, Robyn Schell and David Kaufman

Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, Canada

Keywords: Wii Bowling, Digital Games, Game Attitudes, Older Adults, Social Fun and Competition.

Abstract: This study examined the effectiveness of a Wii Bowling tournament for improving older adults’ attitudes

towards digital games. A total of 142 older adults were recruited from 14 senior centers; 81 were placed in

the experimental group and 61 in the control group. Participants in the experimental group played in teams

of four members formed within each participating site. The 81 participants in the experimental group

formed a total of 21 teams, which played against one another in an 8-week tournament. The findings

indicate that the Wii Bowling tournament was an effective way to improve older adults’ attitudes towards

digital games (t = 2.53, p = .01). Consistent with the findings in previous studies, this research found that

co-located social gaming creates a natural context for fun, immersion, and competition.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Age-related Health Problems

The percentage of older adults in our population has

increased in the past decades and continues to do so.

By 2050, one in five people in the world will be

aged 60 or older (Akitunde, 2012). People are living

longer as a result of better health and living

conditions. However, with advanced age, older

adults experience declines in social contacts,

physical abilities, and cognitive function. Impaired

balance and falls can lead to injury, increased

morbidity, fear of falling, loss of independence,

death, and direct medical costs (Lai et al., 2012).

Cognitive decline is associated with decreased

ability to perform everyday tasks required for

functional independence, such as car driving and

financial management (Boot et al., 2013). What’s

more, many older adults face key social and

psychological challenges such as loneliness,

depression, and lack of social support due to

decreased social contact. Since these changes

negatively affect older adults’ quality of life (Aison

et al., 2002), there are growing needs to understand

and find ways to prevent or reshape age-related

physical and cognitive decline and to increase older

adults’ social interaction. One of the possible ways

that has been gaining researchers’ attention is digital

gameplay.

1.2 Older Adults and Digital Games

Digital games (e.g., action, strategy, role-play,

sports, and casual games) can be complex, offering

flexible activities that use multiple cognitive

abilities. Games that require progressively more

accurate and more challenging judgments at higher

speed, and the suppression of irrelevant information,

can drive positive neurological changes in the brain

systems that support these behaviors. Today, playing

digital games has become a social activity (Ekman et

al., 2011). Online games such as Massively

Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games

(MMORPGs, e.g., World of Warcraft) allow

thousands of players from around the world to

interact with each other in the same virtual

environment. With advances in virtual-reality

interaction technology, somatosensory digital games

that combine traditional digital games and physical

activities provide older adults with alternative

leisure opportunities (Chiang et al., 2012); for

example, the Nintendo Wii Fit includes more than

40 activities such as yoga postures, strength training,

and balance designed to engage the player in

physical exercise.

These games can be played with family and

friends in real-world situations. Face-to-face

contacts and frequent, meaningful social interactions

Zhang, F., Hausknecht, S., Schell, R. and Kaufman, D.

Can a Wii Bowling Tournament Improve Older Adults’ Attitudes towards Digital Games?.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 211-218

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

211

can happen through “interacting with other people,

spending time with friends, watching others play,

chatting and talking about the game, seeing other

people’s reactions and expressions, gloating when

beating a friend, or feeling pride when they win”

(Sweetser andWyeth, p.11). Engagement in social

activities not only meets older adults’ psychological

needs for social interaction, but also keeps them

physically and mentally active – the “use it or lose

it” metaphor.

In addition, games are designed to be fun to play.

They appeal to older adults’ desires and needs for

entertainment

, mental fitness enhancement,

competition and success, a satisfying use of time,

and, in social games, a sense of belonging (Hoppes

et al., 2001, cited in Whitlock et al., 2012). Digital

gameplay is inherently enjoyable and motivating, a

state which can be described in terms of

Csikszentmihalyi’s (2000) flow experience. Flow

describes a mental state of complete absorption,

accompanied by positive feelings. Gamberini et al.

(2008) pointed out that digital games can provide

older adults with new opportunities for leisure and

entertainment, combined with training that avoids

both intimidating task complexity and boredom.

There is now substantial evidence showing that

playing digital games can improve older adults’

physical, cognitive, and psychological health.

Jorgensen et al. (2012) examined postural balance

and muscle strength in healthy community-dwelling

older adults using biofeedback-based Nintendo Wii

training for a period of 10 weeks. Results showed

that the Wii training resulted in significant

improvements in maximal leg muscle strength and

overall functional performance in participants.

Pompeu et al. (2012), investigating the effect of

Nintendo Wii-based motor cognitive training on

activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson’s

disease, found that participants showed improved

performance in activities of daily living after 14

sessions of balance training. Basak, Boot, Voss, and

Kramer (2008) reported on the use of a real-time

strategy video game for the enhancement of

executive control processes of older adults. They

found that after a period of 23.5 hours gameplay, the

experimental group improved significantly more

than the control group in executive control functions

such as task switching, working memory, and visual

short-term memory. Jung, Li, Janissa, Gladys, and

Lee (2009) examined the impact of playing

Nintendo Wii on the psychological and physical

well-being of seniors in a long-term care facility.

Results showed that playing Wii yielded a positive

impact on loneliness, self-esteem, and well-being

among older adults, compared to a control group that

played traditional board games. Previous studies

have also suggested that regular and occasional

gamers exhibit significantly higher levels of well-

being and lower levels of loneliness compared to

non-gamers (Allaire et al., 2013; Jung et al., 2009).

These findings demonstrate the potential of digital

games to improve older adults’ quality of life.

1.3 Older Adults and New Technology

Older adults are stereotypically viewed as having

negative views towards technology. However,

although physical and cognitive declines may

hamper their ability to use technology as effectively

or proficiently as younger people, older adults have

been found to be willing to use technology when

they are aware of the benefits such technology can

offer them (Eisma et al., 2004; Heinz et al., 2013).

Reviewing studies that compare older and younger

adults’ attitudes towards and abilities with

computers, Broady, Chan and Caputi (2010) found

that lack of knowledge of the capabilities of modern

technologies and how to use them is a major

influence on older adults’ avoidance of technology.

Other barriers include confusion regarding usage

procedures, fear of the unknown, lack of confidence,

and lack of understanding of the value of products

and services. Understanding technology as being

personally relevant and useful, as well as

overcoming the initial fears and external factors (e.g.

how one is viewed and treated by others) are crucial

to overcoming those barriers. Overall, Broady et al.

(2010) concluded that older people appear eager to

accept technological advancements and exhibit

attitudes that are as positive as young peoples’

towards the use of computers. In addition, first-hand

experience can trigger older adults' interest and

provide opportunities for improving attitudes

towards a new technology (Bandura, 2001;

Melenhorst, 2002; cited in Gajadhar, Nap, de Kort,

and IJsselsteijn, 2010).

1.4 Research Purpose

Despite potential physical, cognitive, and social

benefits, older adults are far less likely than younger

people to play digital games (McKay and Maki,

2010). Older gamers are playing more and more

games, but only 29% of gamers are over the age of

50 (Galarneau, 2014). In the U.S., some 61% of

gamers are younger than 36-years old

(Entertainment Software Association, 2014). It is

understandable that older adults play fewer digital

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

212

games, as many did not grow up with computer and

information technologies. However, encouraging

their engagement with these new technologies could

help to realize the potential of digital games to

address a variety of health, social-psychological, and

functional needs for older adults.

Social interaction has an important effect on

older adults’ successful aging (Lewi, 2014) and is a

strong motivator among older people for playing

digital games (Rice et al., 2012). Competition is

another important factor that affects their in-game

enjoyment (De Schutter, 2011). Previous research

has shown that playing together in the same place, as

opposed to remotely, significantly contributes to fun,

challenge, and perceived competence in the game as

older adults prefer co-located co-play to playing

with other people online (Gajadhar, de Kort, &

IJsselsteijn, 2008; Gajadhar et al., 2010). Therefore,

the purpose of this study was to examine whether a

co-located Wii Bowling digital game tournament

could improve older adults’ attitudes towards digital

games.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Intervention Tool

In a qualitative focus group study, Diaz-Orueta,

Facal, Nap, and Ranga (2012) identified digital

game features of most interest to older adults: the

social aspect of the experience, the challenge it

presents, the combination of cognitive and physical

activity, and the ability to gain specific skills. Wii

Bowling is a game that offers these features.

Wii Bowling offers a convenient platform for

multiple players. The Wii console allows users to

interact with the game via remote, using natural

body movements that are recognized by motion

sensors. The game action is displayed on a large

screen. Wii Bowling was selected for this study

because: 1) most older adults are familiar with

bowling; 2) bowling and the WII are fun to play; 3)

the game is relatively simple to learn and to play;

and 4) bowling is a social activity that allows a

group to play together.

2.2 Outcome Measure

Participants’ attitudes toward the game were

assessed by 8-items selected from the Computer

Game Attitude Scale (Chappell and Taylor, 1997),

which measures the level of positive attitude toward

digital games. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert-

scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5

(Strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher

level of positive attitude towards the social aspects

of digital game. Its reliability is .79.

2.3 Participants and Procedure

Participants were older adults aged 60 and over. A

total of 142 older adults were recruited from 14

centers, 81 were placed in the experimental group

and 61 were in the control group. The participants in

the experimental group played in teams of four

members formed within each participating site.

Since older adults might have appointments,

commitments, or illnesses that prevented them from

attending a session, only the top three scores of each

game were recorded each week, even if four players

attended that session. This approach allowed some

flexibility when one team member was absent.

A total of 21 teams played against one another in

the tournament. To avoid potential issues (e.g.,

social anxiety, time conflicts) that might have

affected outcomes, team members, team names,

availability and avatar names in the Wii Bowling

game were all decided by participants. Follow-up

interviews found that the teams were formed based

on availability. Before the tournament, participants

had one practice session, where observations and

interviews showed that most participants felt tired

after playing two games in succession. To sustain

participants’ interest to the game but not make them

feel overwhelmed, the experimental group played

two games in one week.

A research assistant (RA) was assigned to each

team. During the eight-week tournament, the RA

visited the site every week, set up the game for the

team, and recorded each member’s score and the

team’s weekly score. A weekly observation protocol

was designed that informed how RAs were to take

field notes, collect feedback, and identify any

problems. The RA also posted each team’s weekly

score on a tournament website and provided the

scores in hard copy to the team

The control group didn’t play digital games

during the tournament, but they were welcome to

watch the gameplay of the experimental group. After

the tournament, both the experimental and control

groups completed the post-test.

Can a Wii Bowling Tournament Improve Older Adults’ Attitudes towards Digital Games?

213

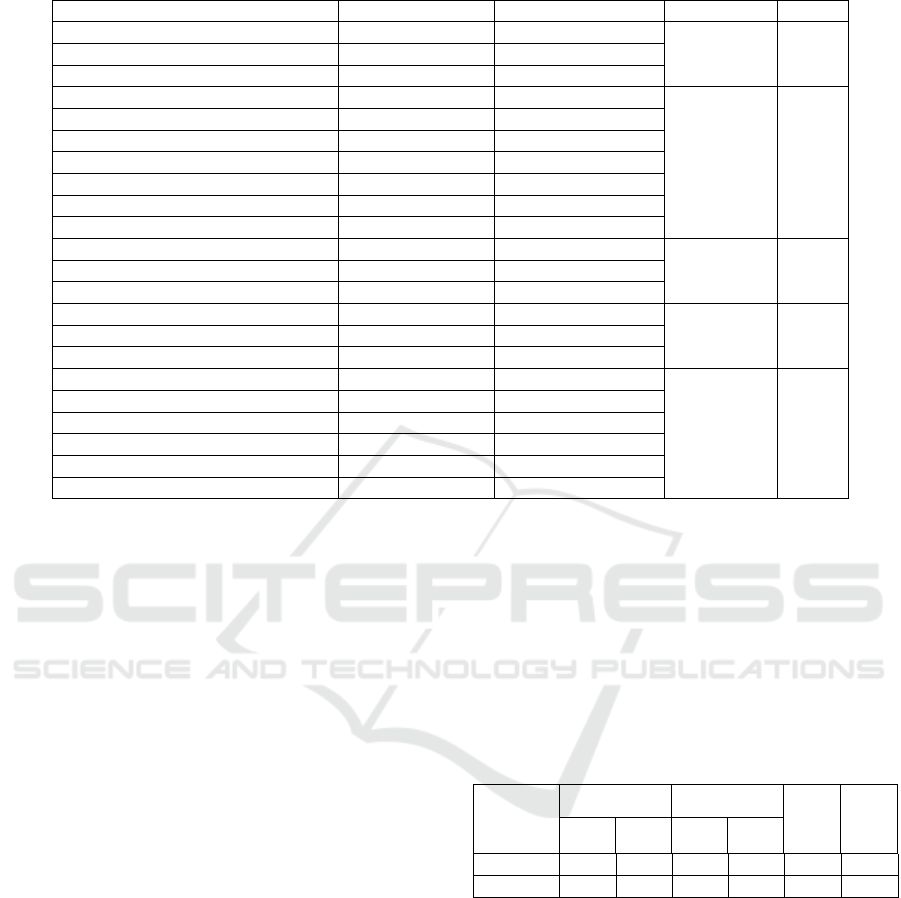

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Participants and Outcome Measure in Each Group.

Variables Contro Group Experiment Group Chi-square p

Gender(frequency, percent)

1.35 .25 Male 13(21.3%) 24(30.0%)

Female 48(78.7%) 56(70.0%)

Age (frequency, percent)

8.33 .14

60-69 5(8.2%) 16(20.0%)

70-74 4(6.6%) 8(10.0%)

75-79 8(13.1%) 16(20.0%)

80-84 19(31.1%) 14(17.5%)

85-89 15(24.6%) 14(17.5%)

>=90 10(16.4%) 12(15.0%)

Current relationship status

3.61 .06

Married/Common law 6(10.9%) 18(24.0%)

Single/Windowed 49(89.1%) 57(76.0%)

Living arrangement

2.58 .11

Alone 44(83.0%) 53(70.7%)

With someone 9(17.0%) 22(29.3%)

Education level(frequency, percent)

.86 .93

Less than high school 4(6.6%) 4(5.1%)

High school or equivalent 24(39.3%) 34(43.0%)

Some college/CEGEP 14(23.0%) 18(22.8%)

Two-year degree 7(11.5%) 6(7.6%)

University degree 12(19.7%) 17(21.5%)

2.4 Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS

Statistics V22. Demographic characteristics of the

participants in each group were compared using chi-

squared analysis to examine whether the two groups

were equivalent at baseline. Then, independent t-test

analyses were conducted to compare the difference

between the two groups both before and after the

intervention. For qualitative analysis the field notes

were imported into MaxQDA for coding. Codes

were collected under major themes

3 RESULTS

Demographic information for both groups is

provided in Table 1. Participants in the two groups

did not differ in terms of gender, age, current

relationship status, living arrangements, or education

level. However, the majority of participants in each

group were single or widowed and lived alone.

Because of this, it is possible that they had smaller

social networks than those in other circumstances.

3.1 Quantitative Results

For game attitudes, there was no statistically

significant difference between the two groups in the

pre-test (t = 1.51, p = .13). As shown in Table 2, the

levels of game attitudes increased from 3.72 (SD =

.58) to 3.89 (SD = .70) in the experimental group ,

but only from 3.54 (SD = .66) to 3.55 (SD = .73) in

the control group. The experimental group generally

had higher levels of positive attitudes towards digital

games than control group. More importantly, the

post-test showed a significant difference between the

two groups (t = 2.53, p = .01).

Table 2: Results of Independent T-Test on Game

Attitudes.

Control Experiment

t p

M SD M SD

Pre-test 3.54 .66 3.72 .58 1.51 .13

Post-test 3.55 .73 3.89 .70 2.53 .01

3.2 Qualitative Results

Data from weekly interviews indicated that the

majority of participants enjoyed playing Wii

Bowling. By analyzing the weekly field notes, five

elements were identified that contributed to

maintaining participants’ interest in Wii Bowling

and to changing their attitudes towards digital

games:

(1) In-Situation Teaching

Team members worked together to accomplish each

team’s objectives. Direct teaching from team

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

214

members was quite frequent, happening whenever a

player wanted to get a strike or had a high possibility

of losing. For example, on one occasion, D wanted

to get a strike (all pins hit down in one throw)

because all of the other three team members had

already gotten one, leading to the following

conversation:

A: Move the line over.

B: Make sure your hand is straight.

A: Get your hand straight.

C: You can do it, D.

(2) Encouragement from Team Members

Encouragement was a key aspect of team members’

social interactions. One player was left-handed, and

her ball always ran slowly. When she didn’t do very

well in one throw, her teammates said, “At least,

that’s a fast bowl” and “It’s good. At least, it’s

straight.” On another occasion, she got many curves

and couldn’t make the ball run straight. When her

bowl ran slowly and gradually changed direction,

her teammates murmured, “Come on, come

on”;”Yes, yes…” Finally, the ball hit the last pin.

Everyone in the room applauded and cheered for her

with “Good for you”; “You have some suspenders.”

At another site, a participant’s vision was so poor

that she needed help to locate the button in the

controller and the pins in the screen, but she did very

well every week. Her teammates said: “You are

remarkable. You always inspire us.” On one

occasion, she had technical problems and needed

several tries to let the bowl go. She was

disappointed, saying “I’m sorry. At least, I let it go,”

but her team members were kind and supportive,

saying “It’s fine”; “That’s OK. You can’t hit them

all the time”; “You participated. It’s fine.”

(3) Audience Support

Audiences played important roles in supporting

players and sustaining their interest and passion

during the tournament. Support from the audiences

made the players believe what they were doing was

interesting. They felt proud of themselves because

they were doing something that they never thought

they could do. As shown in Table 1, approximately

half of the players were aged 80 and over. People at

this age are likely to suffer from some age-related

functional limitations (Bouma, 2000). For example,

at one session an audience member who sat next to a

player and coached that player every week was late

arriving for the game The players were quite

reserved, and didn’t interact with each other as much

as they had in previous weeks. However, once the

audience member walked in, the four players

became alive and said: “We need you, coach.”

(4) Humor

Humor was another key aspect of social interactions

among team members, contributing significantly to

players’ enjoyment of the game. Team members

liked to joke and laugh together during gameplay, as

in the following conversation about a pin that didn’t

fall down:

A: Stupid pins.

B: Silly pins.

C: Not smart pins.

D: The nice pin is going to fall down.

(5) The Game

Wii Bowling enables enactive interactions, or motor

acts used in real life such as swinging arms to play

bowling (Vanden Abeele & De Schutter, 2010).

One advantage of enactive interaction was that

players could focus on hitting the pins rather than

having to learn complex mappings between in-game

actions and specific button presses (Vanden Abeele

& De Schutter, 2010). So, the game was easy to

learn and understand, although difficult to master.

For example, skill was needed to achieve a split

(knocking all pins down in two throws of the ball).

Some participants mentioned minor medical effects

from playing the game; one said that she was

surprised that she didn’t feel arm pain when

swinging her arm.

4 DISCUSSION

The findings of this study support the conclusion

that the Wii Bowling tournament was effective for

improving older adults’ attitudes towards digital

games. In addition, the qualitative data demonstrate

that participants enjoyed the experience of engaging

in the Wii Bowling tournament. Although many

participants had no prior experience with digital

games before the intervention, the majority of them

indicated that they would be interested in playing

digital games in the future.

The possibility of using Wii Bowling to improve

older adults’ attitudes towards digital games is

appealing for many reasons. First, participants were

fully immersed in the game. They were excited and

even danced whenever they got a strike or several

strikes in a row, especially when there was an

audience cheering for them. Second, many

participants mentioned that they enjoyed the

competition and cared about their team’s position

among all the teams. One participant said: “It’s great

to beat another team because we have two teams

here (in an assisted living center).” Third, emotional

Can a Wii Bowling Tournament Improve Older Adults’ Attitudes towards Digital Games?

215

support from team members was a key factor that

contributed a significant part to participants’

enjoyment. Encouragement from team members,

jokes, and applause created a natural social context

in which participants felt free to express themselves.

Fourth, the positive experience of gameplay

improved participants’ confidence with the new

technology. Many participants indicated that they

were proud of themselves; they hadn’t played the

game before the intervention, but they were able to

master the game by the end of the eight-week

tournament. During each session, participants were

provided with directions for each game and

individual assistance from a research assistant. This

on-demand support helped them to acclimate to the

game controls, alleviating potential confusion and

frustration. Last but not least, Wii Bowling was easy

for older adults to interact with since it allowed

participants to interact naturally with the game. The

game also provided clear and positive feedback to

promote players’ self-confidence. Marston (2013)

pointed out that older adults will only invest their

time in such entertainment if they can understand

and see the purpose of their actions.

Nap, de Kort and IJsselsteijin (2009) found that

the majority of older adults have negative

perceptions about multiplayer gaming. Gajadhar et

al. (2010) pointed that older adults’ negative

perceptions about playing against other human

players could be caused by the fear of failure. In this

study, many participants highlighted their positive

experiences of competing with other teams.

Therefore, we suggest that in the context of co-

located gameplay, older adults enjoy team

competition or social competition. The findings of

this study support Gajadhar et al.’s (2010) conclusion

that co-located social gaming is a “mix of social fun

and involvement and social competition” (p.80).

There are two limitations to this study. One

limitation is that the participants were recruited

based on their availability and interest in this study.

Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to other

populations, such as older adults who are not

interested in Wii Bowling. Another limitation is that

health condition was not one of the sample inclusion

criteria. Some participants had to sit to play due to

Parkinson’s disease or physical impairments. We are

unsure whether participants’ physical health affected

attitudes towards playing Wii Bowling.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We are confident that the Wii Bowling

tournament provided positive gaming experiences to

the older adults in this study and was an effective

way to improve their attitudes towards digital

games. Older adults are willing to use digital games

if they are motivated and understand the purpose of

their actions. These findings could encourage other

researchers to investigate in more depth how to help

older adults benefit from digital games. In addition,

the social use of Wii Bowling may enable older

adults to take-up this activity within many senior

centers, thus enriching their daily activities and

enhancing their physical and cognitive function and

social interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

for supporting this project financially through a four-

year Insight grant.

REFERENCES

Akitunde, A. (2012). Aging Population: 10 Things You

May Not Know About Older People. Retrieved from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/10/02/aging-

population_n_1929464.html.

Aison, C., Davis, G., Milner, J., & Targum, E. (2002).

Appeal and Interest of Video Game Use Among the

Elderly. Retrieved from http://www.booizzy.com/jrmil

ner/portfolio/harvard/gameselderly.pdf.

Allaire, J. C., McLaughlin, A. C., Trujillo, A., Whitlock,

L. a., LaPorte, L., & Gandy, M. (2013). Successful

aging through digital games: Socioemotional

differences between older adult gamers and Non-

gamers. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1302–

1306. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.014.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass

communications. In J.Bryant & D.Zillman (Eds),

Media effects: Advances in theory and research (2nd

ed.) (pp.121-153). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Basak, C., Boot, W.R., Voss, M.W, & Kramer,

A.F.(2008). Can Training in a Real-Time Strategy

Digital Game Attenuate Cognitive Decline in Older

Adults? Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 765-777.

Boot, W.R., Champion, M., Blakely, D.P., Wright, T.,

Souders, D.J., & Chamess, N. (2013). Video games as

a means to reduce age-related cognitive decline:

attitudes, compliances, and effectiveness. Frontiers in

Psychology, 4, 1-9.

Bouma, H. (2000). Document and interface design for

older citizens. In P. Westendorp, C. Jansen, & R.

Punselie (Eds.), Interface design & document design

(pp.67-80). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

216

Broady, T., Chan, A., & Caputi, P. (2010). Comparison of

older and younger adults’ attitudes towards and

abilities with computers: Implications for training and

learning. British Journal of Educational Technology,

41(3), 473-485.

Chappell, K.K., & Taylor, C.S. (1997). Evidence for the

reliability and factorial validity of the computer game

attitude scale. Journal of Educational Computing

Research, 17(1), 67-77.

Chiang, I.T., Tsai, J.C., & Chen, S.T. (2012). Using Xbox

360 Kinect games on enhancing visual performance

skills on institutionalized older adults with

wheelchairs. In Proceedings of Fourth IEEE

International Conference on Digital Game and

Intelligent Toy Enhanced Learning - DIGITEL

2012(pp. 263-267). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE

Computer Society. doi:10.1109/DIGITEL.2012.69.

Csıkszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Beyond Boredom and

Anxiety. Experiencing Flow in Work and Play. 25th

Anniversary Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Deary, I.J., Corley, J., Gow, A.J., Harris, S.E., Houlihan,

L.M., Marioni, R.E…Starr, J.M. (2009). Age-

associated cognitive decline. British Medical Bulletin,

92, 135-152.

De Schutter, B. (2011). Never Too Old to Play: The

Appeal of Digital Games to an Older Audience.

Games and Culture, 6(2), 155-170.

Diaz-Orueta, U., Facal, D., Nap, H.H., & Ranga, M.M.

(2012). What Is the Key for Older People to Show

Interest in Playing Digital Learning Games? Initial

Qualitative Findings from the LEAGE Project on a

Multicultural European Sample. Games for Health

Journal. 1(2), 115-123. doi:10.1089/g4h.2011.0024.

Eisma, R., Dickinson, A., Goodman, J., Syme, A., Tiwari,

L. & Newell, A.F. (2004). Early user involvement in

the development of information technology-related

products for older people. Universal Access in the

Information Society, 3, 131-140.

Ekman I, Chanel G, Järvelä S, Kivikangas JM, Salminen

M, Niklas Ravaja N (2012) Social interaction in games

measuring physiological linkage and social presence.

Simulation & Gaming 43(3): 321-338.

doi:10.1177/1046878111422121.

Entertainment Software Association (2014) Essential facts

about the computer and video game industry.

Washington, DC: Entertainment Software Association.

Retrieved from http://www.theesa.com/wp-

content/uploads/2014/10/ESA_EF_2014.pdf.

Gajadhar, B.J., de Kort, Y., & IJsselsteijn, W. (2008).

Shared fun is doubled fun: player enjoyment as a

function of social setting. In P.Markopoulos, B. de

Ruyter, W.IJsselsteijn & D.Rowland (Eds.) Fun and

Games (pp.106-117). New York: Springer.

Gajadhar, B.J., Nap, H.H., de Kort, Y.A.W., &

IJsselsteijn, W.A. (2010). Out of Sight, out of Mind:

Co-Player Effects on Seniors’ Player Experience.

Proceedings of Fun and Games, Leuven, Belgium.

Galarneau, Lisa. (2014). 2014 Global Gaming Stats:

Who’s Playing What, and Why? Retrieved from

http://www.bigfishgames.com/blog/2014-global-

gaming-stats-whos-playing-what-and-why/

Gamberini, L., Alcaniz, M., Fabregat, M., Gonzales, A.L.,

Grant, J., Jensen, R.B…Zemmerman, A. (2008).

Eldergames: Videogames for empowering, training

and monitoring elderly cognitive capabilities.

Gerontechnology, 7(2), 111.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.40

17/gt.2008.07.02.048.00.

Ghosh, R., Ratan, S., Lindeman, D., & Steinmetz, V.

(2013). The new era of connected aging: A framework

for understanding technologies that support older

adults in aging in place. Oakland, CA: Center for

Technology and Aging.

Heinz, M., Martin, P., Margrett, J.A., Yearns, M., Franke,

W., Yang H.I….Chang, C.K. (2013).Perceptions of

Technology among Older Adults. Journal of

Gerontological Nursing, 39(1), 42-51.

Hoppes, S., Wilcox, T., & Graham, G. (2001). Meanings

of play for older adults. Physical Occupational

Therapy in Geriatrics, 18(3), 57-68.

Jorgensen, M.G., Laessoe, U., Hendriksen, C., Nielsen,

O.B.F., & Aagaard, P. (2012). Efficacy of Nintendo

Wii Training on Mechnical Leg Muscle Function and

Postural Balance in Community-Dwelling Older

Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journals of

Gerontology: MEDICAL SCIENCES, 1-8.

Jung, y., Li, K.J., Janissa, N.S., Gladys, W.L.C., & Lee,

K.M. (2009). Games for a Better Life: Effects of

Playing Wii Games on the Well-Being of Seniors in a

Long-Term Care Facility, Proceedings of the Sixth

Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment.

NY: USA.

Lewis, J. (2014). The Role of the Social Engagement in

the Definition of Successful Ageing among Alaska

Native Elders in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Psychology &

Developing Societies, 26(2), 263–290.

Lai, C.H., Peng, C.W., Chen, Y.L., Huang, C.P., Hsiao,

Y.L., & Chen, S.C. (2012). Effects of interactive

digital-game based system exercise on the balance of

the elderly. Gait Posture, 1-5.

Marston, H.R. (2013). Digital Gaming Perspectives of

Older Adults: Content vs. Interaction. Educational

Gerontology, 39(3), 194-208.

McKay, S.M., & Maki, B.E. (2010). Attitudes of older

adults toward shooter video games: An initial study to

select an acceptable game for training visual

processing. Gerontechnology, 9(1), 5-17.

Melenhorst, A.S. (2002). Adopting communication

technology in later life: The decisive role of benefits.

Doctoral dissertation. The Netherlands: Eindhoven

University of Technology.

Nap, H.H., de Kort, Y.A.W., & IJsselsteijn, W.A. (2009).

Senior Gamers: Preferences, Motivations and Needs.

Gerontechnology, 8, 247-262.

Pompeu, J.E., Mendes, F.A., Silva, K.G., Lobo, A.M.,

Oliveira, T.P., Zomigani, A.P., & Piemonte, M.E.

(2012). Effect of Nintendo Wii-based motor and

cognitive training on activities of daily living in

patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized

clinical trial. Physiotherapy, 98, 196-204.

Can a Wii Bowling Tournament Improve Older Adults’ Attitudes towards Digital Games?

217

Rice, M., Cheong, Y. L., Ng, J., Chua, P. H., & Theng,

Y.L. (2012). Co-creating games through

intergenerational design workshops. In Proceedings of

the Designing Interactive Systems Conference on -

DIS ’12 (pp. 368–377). Newcastle, UK.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.2318012.

Sweetser, P., & Wyeth, P. (2005). GameFlow: A Model

for Evaluating Player Enjoyment in Games. ACM

Computers in Entertainment, 3(3), 1-24.

Vanden Abeele, V., & De Schutter, B. (2010). Designing

intergenerational play via enactive interaction,

competition and acceleration. Personal and

Ubiquitous Computing, 14(5), 425–433.

Whitlock, L. A., McLaughlin, A. C., &Allaire, J. C.

(2012). Individual differences in response to cognitive

training: Using a multi-modal, attentionally

demanding game-based intervention for older adults.

Computers in Human Behavior, 28(4), 1091-1096.

doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.01.012.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

218