A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries

Feno Heriniaina R.

College of Computer Science, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

Keywords: Censorship, Human Computer Interaction, Privacy, Virtual Private Networks.

Abstract: Online surveillance has been increasingly used by different governments to control the spread of information

on the Internet. The magnitude of this activity differs widely and is based primarily on the areas that are

deemed, by the state, to be critical. Aside from the use of keywords and the complete domain name filtering

technologies, Internet censorship can sometimes even use the total blocking of IP addresses to censor content.

Despite the advances, in terms of technology used for Internet censorship, there are also different types of

circumvention tools that are available to the general public. In this paper, we report the results of our

investigation on how migrants who previously had access to the open Internet behave toward Internet

censorship when subjected to it. Four hundred and thirty-two (432) international students took part in the

study that lasted two years. We identified the most common circumvention tools that are utilized by the

foreign students in China. We investigated the usability of these tools and monitored the way in which they

are used. We identified a behaviour-based privacy threat that puts the users of circumvention tools at risk

while they live in an Internet-censoring country. We also recommend the use of a user-oriented filtering

method, which should be considered as part of the censoring system, as it enhances the performance of the

screening process and recognizes the real needs of its users.

1 INTRODUCTION

Throughout the world, the Internet is being used in

different contexts to drive ideas, views and opinions

in virtual communities and networks. In January

2011, during the protest against the government in

Egypt, the means used for spreading ideologies such

as Twitter and Facebook were blocked, and a five-day

Internet disruption was reported. Libya also reported

instances of Internet disruption after the protests

against their government started in February 2011

(Dainotti et al., 2011). Starting in early 2014, Turkey

has blocked the IP addresses to Twitter and YouTube

after what was judged to be sensitive information by

the government had been leaked on these social

media platforms. The world has gone virtual, causing

the dependence on the Internet to grow rapidly and to

an unprecedented level. The pace of adoption of the

Internet has only been made faster by people not only

being able to read information, but also being able to

create and distribute content easily. China, being the

most populated country in the world with 1.4 billion

people as of 2015, is also first in online presence, with

more than 500 million Internet users. To preserve

state security along with social and public interest,

Internet security is pressing. The government has

used different measures including the Internet

censorships in the effort to control the access and

publication of any online content judged

inappropriate. Many local and international websites

that use those social utilities to connect with people

(i.e., social networking websites) and web tools that

provide access to the world information (i.e., search

engines, news, etc.) have been greatly affected by this

measure. A complete ban is sometimes used on

specific IP ranges when the servers are out of the

reach of local authorities’ jurisdiction.

Facebook.com has been blocked in Mainland

China since July 2008. It had over one billion active

users as of October 2012 (Rodriguez, 2013), and this

number has not stopped growing. Facebook CEO

Mark Zuckerberg, although wishing to connect the

whole world, finds China extremely complex, and he

is taking his time defining the right strategy for

dealing with it (Kincaid, 2013). Despite all that,

Facebook is still the top most used social website by

foreign students in China for catching up with their

families and friends living abroad.

After the long effort to awaken China, a once-

dormant economic giant (Zuliu and S., 1997), the

country is now among the top five world destinations

372

R., F.

A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries.

DOI: 10.5220/0005739203720379

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2016), pages 372-379

ISBN: 978-989-758-167-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

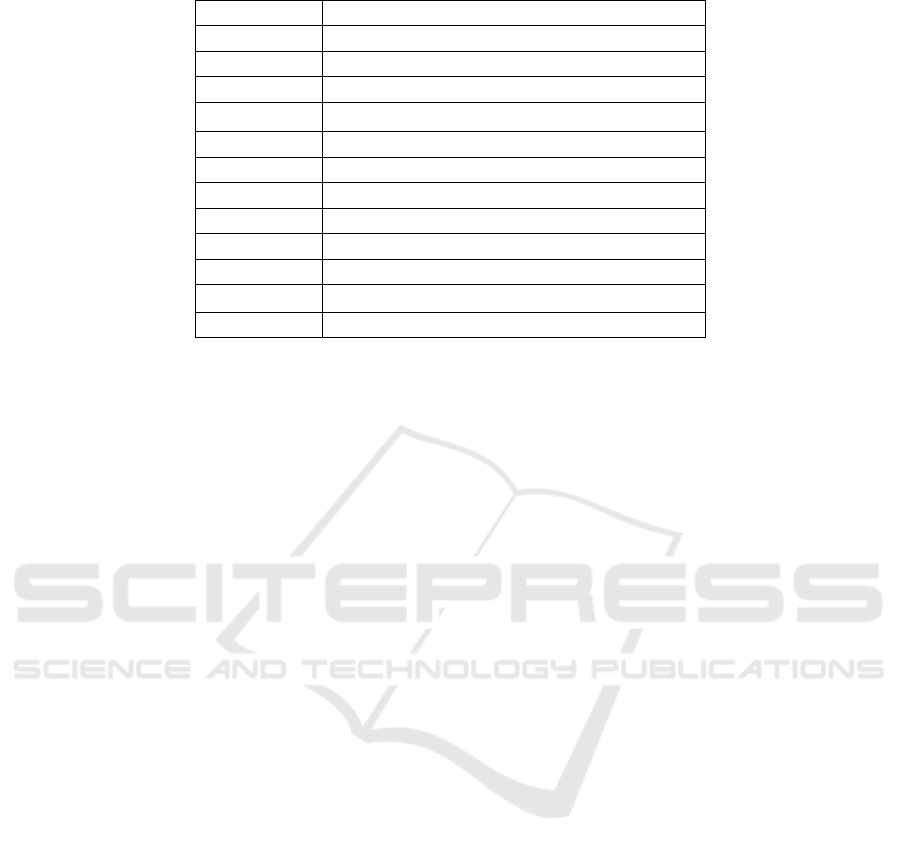

Table 1: List of the major technologies used by our survey respondents to go through the great firewall.

Tools name Links*

WebFreer http://76.164.202.93/download/WebFreer_1.1.0.0.exe

XskyWalker http://bbs.0678life.com

GoAgent http://code.google.com/p/goagent/

FreeGate http://www.dit-inc.us/freegate.html

Psiphon https://psiphon.ca/index.html

Lantern https://getlantern.org/

Uproxy https://www.uproxy.org/

Vtunnel http://vtunnel.com/

Wallhole1 http://wallhole1.com

VPN Book http://www.vpnbook.com/webproxy

StrongVpn http://www.strongvpn.com/

Astrill https://www.astrill.com/

* some of the tools listed above don’t have official websites so we have provided the links from where we can download the installation

application file.

for businessmen and students. In 2014, an estimated

37,000 international students were granted Chinese

scholarships. By 2020, China is expected to host up

to 500,000 international students (CSC., 2013). The

government is investing ardently in better facilities to

make the stay of the international students a pleasant

journey (CSC., 2015). But there is a huge gap

between the Chinese culture and the cultures of

China's neighbouring countries. This difference is

greater when it compared with the other countries

around the world. Pursuing studies in China is just a

different life event for students from outside the

Asian continent.

The Internet being a main tool for all of these

migrants, they are consistently finding ways for

accessing their desired content online. Furthermore,

there are numerous free, practical tools (e.g.,

Freegate, Goagent, Webfreer, X-Walker, etc.) and

methods available to bypass the Internet limitation

controls. Not wanting to be left without connecting

with their friends and loved ones, most international

students living in China turn to the use of these free

tools.

Although the Internet traffic might often be

exposed to potential eavesdroppers; and even though

standard encryption mechanisms cannot always

provide sufficient protection (Backes et al., 2013),

when the human desire predisposes, nothing can stop

these users from connecting with those they love. A

study by Chellappa et al., in 2005 has shown that

users are willing to trade-off their privacy concerns in

exchange for benefits such as convenience

(Spiekermann et al., 2001); (Chellappa et al., 2005).

We assume that most of the time, users of these

circumvention tools feel satisfied as long as they are

given an easy-to-use (and free) application with

access to blocked online content and moderately fast

data transfer. We also assume that few of them

actually give considerations to anonymity and

privacy risks. Identifying these as weaknesses that

could easily be exploited to become threats to their

privacy, we have started our research to learn the

users' behaviour toward censorship to prove the

veracity of our stated assumptions. In our case study,

we chose to investigate the way the international

students access Facebook from Mainland China, as

this is the most used compared to others.

Studies have looked at censorship and Internet

filtering in China (Walton, 2001), its specific

capabilities (Clayton et al., 2006) and the occurrence

of the national filtering (Xu et al., 2011). They are all

purely technical, and none has considered the user

which is a key player in the whole system. Using a

technique that combines surveys, interviews, and

investigations of user

interactions with the Chinese

Internet, we will bring some relevant insights into the

way the current circumvention tools are used. During

the process, we face several challenges. We need to

collect data from a large number of international

students in China regarding the way they cope with

the Internet censorship and ensure them that their

identity won’t be unveiled. Second, we must inspect

the different tools that are used by these international

students, in different cities, allowing us to understand

their propagation, their selection, and their usability.

The output of this research is of two folds. We learn

about the user’s choice and acceptance of a given

circumvention tool. We identify a weak spot affecting

Internet users located in Internet censoring countries.

For our implementation, we built an experimental

application that provides the open Internet and

monitor the users interactivity with it.

A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries

373

This paper does not attempt to offer a description

of the tools that work best for students in China; we

mainly focus on the availability and the driving force

that guides users in accessing different tools. This will

be the first study of its kind which attempts to

understand the way international students (migrants)

use and select different Internet circumvention tools

in an Internet censoring country.

The remaining part of this paper is organized as

follows: the second section will show the extent of the

desire for people to use the uncensored Internet.

Section three exposes the international students'

strong desire to connect with their friends on

Facebook despite Internet censorship. Given all the

conditions presented in section two and three, in

section four we introduce how an attacker can

efficiently access Facebook account information in a

simplistic and seamless manner. In section five, we

present an overview of our implementation with the

results. The last section six is left for the conclusion

and discussion.

2 DESIRE FOR NETIZEN TO USE

UNCENSORED NETWORK

Four years after the Internet connectivity was

officially established in 1994 in China (Yang, 2003),

the Golden Shield Project also known as the Great

Firewall of China (GFC) started and began processing

in 2003. It is a digital surveillance and censorship

network operated by the Chinese Ministry of Public

Security. In its early stage, the system in place for the

digital surveillance was not able to filter secure traffic

(Walton, 2001) Virtual private network (VPN),

secure shell (SSH), and tunneling protocols were

among the most efficient methods for circumventing

the GFC. Late in 2012, many companies providing

virtual private network services to users in China

stated that the Great Firewall has become able to

learn, discover and block the encrypted

communications. Some have noted that the Internet

service providers kill connections where a VPN is

detected (Guardian., 2011). Such, again proved that

the computing environment changes so much and

trying to stay ahead of Internet censorship is a cat and

mouse game.

Nowadays, many individuals and organizations

are joining forces and standing for a single open

Internet. One of the largest network promoting open

and anonymous Internet is Tor, available at

torproject.org (Danezis, 2011). Since the release of

the Tor Browser application to the general public, its

number of users has not stopped growing. But

although Tor should be working in China (Arma,

2014), during our testing in different locations within

two years, it never worked for us.

Goagent (https://github.com/goagent/goagent) is

another network circumvention software that is open

source and supports multiple operating systems.

Goagent was almost always working during our two-

year monitoring and testing. It is also very well

accepted by Chinese Internet users. Its only weak

point is the installation phase, which requires

tinkering that most potential users would just give up

after engaging in the first few steps.

Freegate (http://dit-inc.us/freegate.html) is

another well-reputed circumvention tool used by the

Chinese netizens. The software is very easy to use and

is among the ones that worked in circumventing the

GFC.

Webfreer and XskyWalker are two software

browsers that also circumvent the GFC and are well

adopted by students. Both applications require to be

installed and were only available for Windows

operating systems. Now, the XskyWalker has been

ported to Android and is also getting much

appreciation from the users.

The list of the free circumvention tools that can be

used in China does not stop there but these are the

ones that we choose to investigate, as they were what

most international students were using on their

computers during the time of our investigations. A list

of the ten most used circumvention tools by the

international students studying in China is presented

in Table 1. 97% of our participants in the survey

introduced in the next section have been at least using

one of these circumvention tools during their stay in

China, a flagrant evidence for their needs of an open

Internet.

3 NETIZEN EAGER TO USE

FACEBOOK

Since the date Facebook could not be accessed freely

within Mainland China, a significant number of local

social networking websites have seen their genesis

within the local market. Despite this restriction, many

are still able to access and maintain their Facebook

accounts. What circumvention tools do they use?

How do they get hold on those tools? We take the first

step in answering the above questions. We initiate a

survey followed by an interview. We have

approached 432 international students, with at least a

high school degree, aged between 18 to 35, and all

ICISSP 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

374

studying for at least one semester in China. We went

door to door to make sure that each respondent is an

international student. The sample was mixed in

gender and had representatives of people from all

different continents. They were physically located in

different universities and provinces in China. All

participants were answering the questionnaire

followed with an interview to determine their

behaviour toward censorship. Because of the ever-

changing context of the Internet censorship condition,

we have had two series of surveys followed by

interviews within two years. Upon completion of the

surveys, a list of the most used circumvention tools

has emerged (Table 1).

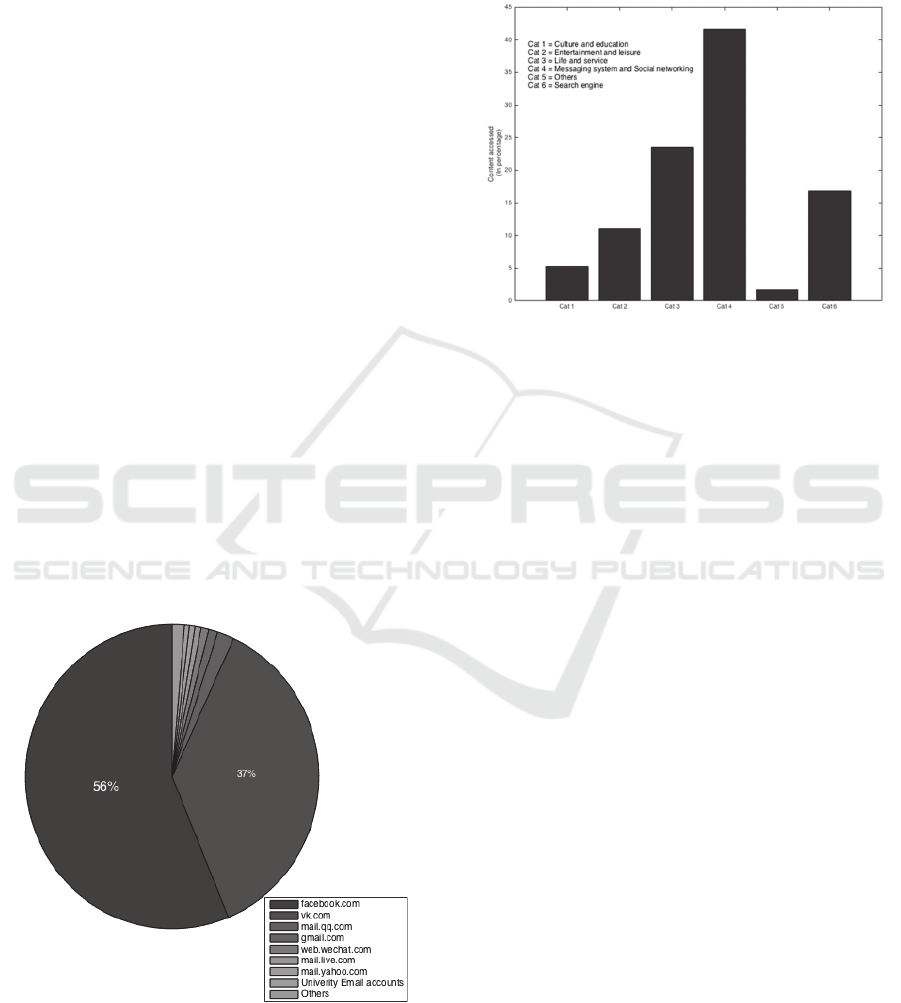

In the meantime, in order to have a real knowledge

of the international students use of the Internet while

pursuing their studies in China, we have contacted

some foreign students and 20 allowed us to retrieve

their browsing histories for the last 200 days. These

students were not informed prior our data extraction

in order to not influence their normal daily online

activities and allow them to delete some privately

visited content. This is one of the main reasons why

it was hard for us to retrieve more data from more

users. We have cleaned and analysed the data, but

because of page limitation we just provide an

histogram of our respondents accessed websites

organized by category in figure 2 and the partitioning

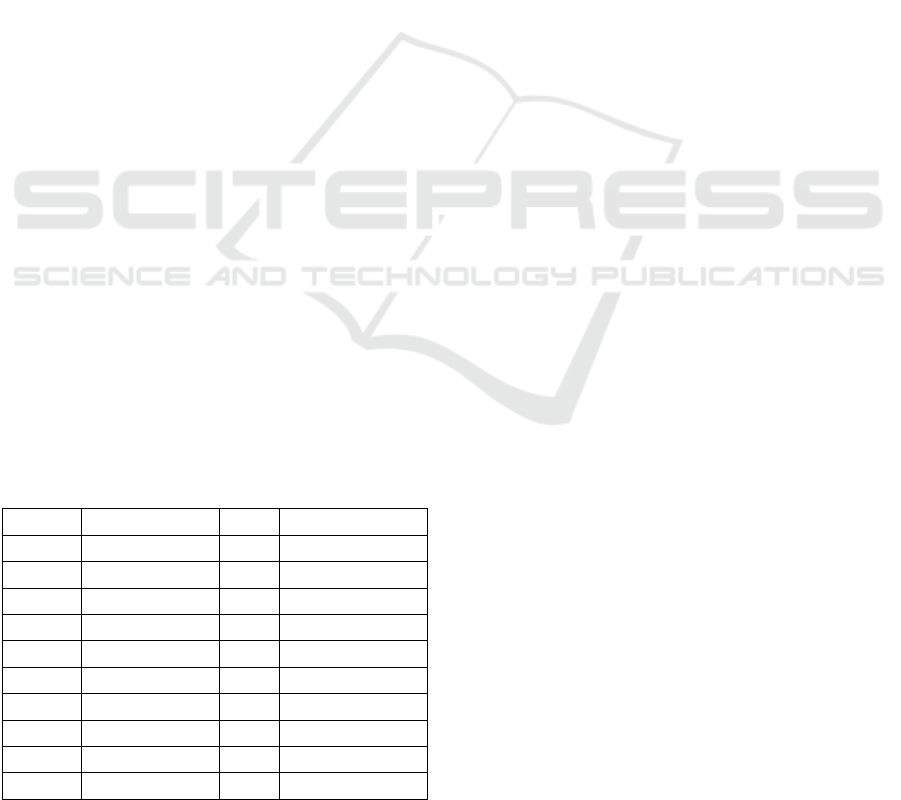

of use of messaging systems used in figure 3. The

messaging system and social networking services are

the most accessed content by the international

students and Facebook takes the fist place.

Figure 2: Percentage of the online content accessed by the

international students in China organized by categories.

After a further analysis of the data we have

collected, we could identify that up to 95% of our

respondents who already used Facebook in their

home countries are still able to access and maintain

their Facebook accounts while in China. Those

students use diverse tools to access Facebook and

other censored websites.

Figure 3: A report of the messaging system and social

networking websites use by the foreign students in China.

We have grouped the used circumvention

technologies in two categories: paid and free tools.

98% of our survey respondents that are Facebook

users are using free applications and services to get

around the censorship. The data has also shown that

the international students in China have a preference

for using applications that are run or installed on their

operating systems compared to web-based services

such as www.vtunnel.com. This is mainly because

almost all the websites that provide information and

circumvention services are blocked in China. Those

who were responding to our survey, were relying on

tools that they downloaded before entering the

country or tools that their friends in the same situation

are using.

Apart from the application being free, the

international students’ choice when selecting a

circumvention tool is made based on what tools are

available, their user friendliness, their efficiency in

connecting to the world Internet, and last but not

least, their connection speed. These are the main

requirements of our respondents when selecting the

tools to use, and not even one was pertinent to

security. We consider such behaviour from these

international students to be exposing themselves to

potential threats toward their online information.

A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries

375

4 HOW AN ATTACKER CAN

EASILY ACCESS FACEBOOK

ACCOUNT INFORMATION

FROM A SEAMLESS MANNER

As the number of Facebook users does not stop

increasing, so does the amount of users’ personal

private data available in these networks. This social

networking platform has become another target of

high interest for attackers to collect data and to

engage in nefarious activities. In this paper, we

present how an attacker can exploit and access users'

Facebook account based on countries where it is

censored. As mentioned earlier, we could know that

the international students are more likely to connect

on Facebook and pass through the great firewall of

China using free tools and services. They only have

three main requirements apart from the service being

free which are availability, efficiency (speed and

connection reliability), and the tools’ user-

friendliness.

We have tested all the application-circumvention

tools listed in the table 1 and calculated the latency in

loading each of the 20 top websites in table 2. We

discovered that the acceptable connection speed for a

tool that can bypass the GFC and be able to maintain

its reputation while keeping users using it starts from

a modest speed of 0.41 Mbps. Among the tested tools,

none could ensure uninterrupted connection to the

world Internet. The applications which are able to

relay to the Internet with the minimum disconnection

interruptions and able to maintain a moderate speed

are the most used. The international students are also

selective for the applications that are easy in

manipulation and quick to setup during installations

phase.

Table 2: List of the top 20 sites (from alexia.com, early

2015).

N.

URLs

N.

URLs

#1

google.com

#11

google.co.in

#2

facebook.com

#12

linkedin.com

#3

youtube.com

#13

live.com

#4

baidu.com

#14

sina.com.cn

#5

yahoo.com

#15

weibo.com

#6

wikipedia.org

#16

yahoo.co.jp

#7

amazon.com

#17

tmall.com

#8

twitter.com

#18

google.co.jp

#9

taobao.com

#19

google.de

#10

qq.com

#20

ebay.com

When a user first accesses his Facebook account

through a proxy or when a login is done from an

uncommon location, the Facebook system might ask

him to go through some test verifications to prove

account ownership. Once the user passes the test and

is granted access to his account, the next time the

same account logs in from the same IP address

(considering that the accounts are set with Facebook’s

default security settings), it is unlikely that Facebook

will ask the user to prove again account ownership.

Based on that, the user’s trust in tools can now be

an attacker’s weapon. An attacker can setup up a

server, make client software to be run on the targeted

users’ computers, and publish to make it available to

them. The client software will set and define the

connection between the user and the server that not

only provides the open internet but also collects

whatever data that might be of value to the attacker.

In such a condition, the attacker could already use

deep packet inspection to monitor the traffic and

collect log reports (Mahmood, 2012). In further

crafting the client application, the attacker could get

access to the login and password. This method is still

effective when the user uses HTTPS during log in

because the client application could be set to extract

the credentials before they get encrypted (figure 4).

public void btn_action(View view) {

//Get user credentials

String user_login = et_login.getText().toString();

String user_password = et_pass.getText().toString();

//Retreive the credentials

SendToServer(user_login, user_password);

//Todo: Do what needs to be done with the credentials

}

Figure 4: Snippet for retrieving the credentials in Freer.

Despite Facebook’s efforts in maintaining a safe

and trusted environment (Facebook, 2013), such a

security threat is still hard to breakdown as it is

entirely the user’s attitude and behaviour that exposes

full control of the communication channel to the

attacker.

With the raise in use of smartphones, an attacker

could also target mobile devices. Moreover, the

threat is even ardent when the official applications for

those devices don`t work and an attacker is able to

provide alternatives. Taking the case of Facebook,

without an official Facebook application that works

in countries censoring the Internet like China. Thus

an attacker can simply craft an application that

provides access to Facebook while gathering users’

data and make that application available to those in

need.

ICISSP 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

376

5 IMPLEMENTATION

With the tendency for youth to access their Facebook

account through mobile devices and with the

restrictions that affect Facebook users in China, they

won’t be able: to see what their friends are up to, to

share updates including photos and videos, to get

notified when friends are liking or commenting on

any of their previous posts, and to chat and engage

into group conversations within their networks. That

is a big handicap, and most of those who are already

on Facebook before entering such an internet

censored condition, instead of coping with the

situation will happily use any alternative applications

that will allow them to join the social network back

especially when there are free solutions. They would

adopt any available solutions, which are efficient

enough for what they claim to provide and even better

if they are user-friendly.

Aware of such users` tendency, an attacker, can

exploit and craft a malicious proxy that provides

Facebook access to those living in Internet-censoring

countries. In the surveys we run, we could produce a

non-exhaustive list of the circumventions tools (Table

1) used by the respondents who are all international

students in China. We have investigated these tools

especially in term of usability and we have studied

how people interact with these technologies. We

consider the following as good tasks for analyzing the

usability of each tool of these tools: installation

process, accessing a Facebook page, viewing some

photo-albums on Facebook. Our measures are

learnability, connection speed, user preference,

memorability and efficiency.

XSkyWalker and WebFreer took the lead in the

analysis results due to their ease of installation and

intuitive user interfaces very similar to the well

reputed web browser Google Chrome. XSkyWalker

was favoured as results of its clean look without

disruptive ads and the auto switch between the

connection to the local internet and the world internet

based on connection restrictions.

To simulate a malicious proxy, we developed

Freer, an application for Android devices focused on

user needs and context. Freer is a user-oriented

application, and its first installation settings have

been reduced to the minimum. For the

implementation, we:

a. Setup a proxy channel (this part is not covered in

this paper).

b. Make an Android application that mimics the

mobile version of the Facebook homepage, visible

at https://m.facebook.com

c. Add the scripts that extract the login and

password, prior to authentication of the user on

the Facebook server.

To prove that retrieving user information based on the

condition mentioned earlier is very easy to achieve,

we intentionally chose to use a simple webView (an

android view) for implementing Freer. To see its

efficiency, we made the application accessible for

downloading to our 50 volunteers.

With a Facebook user account set with the default

security settings, at this stage Freer is working

perfectly. However, Facebook has different security

settings available to the users that are: Secure

Browsing, Login Notifications, Login Approvals,

Code Generator, App Passwords, Trusted Contacts

and Recognized device. Some of these security

features, if activated, can limit the efficiency of the

Freer application.

Knowing that the user does not have other free,

effective and official alternatives for accessing what

they need, we have updated Freer to ask explicitly for

the users’ cooperation for the well functioning of the

application. For all users that are using Freer and have

Login Approvals activated, we set Freer to request

them explicitly to deactivate this security setting to

leverage its full power. In practice, as soon as we

detect that the user account has Login Approvals

activated if the user persists in using Freer without

changing this setting, we will tease him by partially

loading the content and then showing an error

requesting full permission to access the account. With

no official Facebook application that can bypass the

Great Firewall of China and give Facebook users’

connection to their loved ones, those who took part in

our experiments willingly disabled the Login

Approvals from their accounts.

Our approach is not focused on a technical way to

breach the security in place. Here we intend to prove

that the users are willing to get passed all these

security steps to get what they want.

To play on the users’ emotion and tease them, we

find it most efficient to allow them to access all

Facebook content smoothly and freely within the first

few minutes of use of Freer. If any of the two

previously mentioned security settings is enabled,

then Freer will start displaying the warning requesting

the user to disable the optional security settings.

Moreover, those who are using Android and are

residing in China have been slowly cultivated to get

past security warnings because each time they have to

install an application on their device, they always

need to "allow installation of apps from unknown

sources" for side loading.

A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries

377

6 CONCLUSION AND

DISCUSSION

User privacy is vital in online services, but it is hard

to defend against some attacks when the user is

voluntarily contributing to the breach of security as

presented in the above sections. Leakage of personal

information has often slandered people’s reputation

and many times invited spamming, stalking and other

malicious attacks. This degree is rising when it gets

to online social networks as the friends’ information

of a corrupted account is also getting exposed to the

attacker.

In this paper, we have shown that it is easy to lure

users to install and use a malicious proxy application

to access Facebook in China. However, such a

scenario can be broadened to a general case where

people are using free and closed source

circumvention application to access restricted

information from the Internet.

From 2009 onwards, despite being the most used

social networking website used by foreigners for

connecting to the rest of the world, Facebook has

been banned in China. This situation forces users to

be somehow active in finding circumvention methods

and often put their privacy at risk. In our

implementation of Freer, we have shown that only the

least technical skill is needed to breach security

features offered to the users and that they even

voluntarily contribute to the well functioning of the

application as long as it helps them get what they

need. Freer has been intentionally designed in a

simplistic way to show that breaching the security of

the system could be achieved mainly with the help of

the users.

There are many entities trying to fight to connect

the world through the Internet. International

corporations should not minimize the presented threat

that users living in Internet censoring-countries are

facing. Efficient counteroffensive should be taken

into account, and further research in such orientation

should supplement this work.

Each coin has two sides and so, in our proposal

for solutions we provide three folds:

First, the corporations and entities that have their

contents restricted should support some of the

ongoing projects on providing free circumvention

tools. Also, they should support these projects in

terms of branding and awareness. In doing, the users

in need of these resources will at least be sure that

they are using official and trustworthy applications.

Second, the organizations or entities that are

developing the circumvention techniques should

focus more on providing user-friendly tools. We

could discover from our investigation that although

GoAgent is working well in China, many of the

potential users were reluctant to use it because of the

complexity of the first setup. XskyWalker in the other

hand, although using the same architecture, has

attracted more users mainly because of its simple

installation procedure.

Third, national situations and cultural traditions

differ among countries, and so apprehension about

Internet security also differs. Concerns about Internet

security of different countries should be fully

respected (Han, P., 2010). In search of a secure

common ground for cyberspace for peace while

promoting development through exchanges, Internet

users should be part of the security and should be

considered part of the system. If provided something

that will not help them in achieving their tasks, people

will always be constrained to find alternative

solutions, which might compete, and breach the

security put in place. Moreover, some third-part can

take advantage of the situation for running his

exploits. So, when building a security system, the

following should be addressed: What do the users

need to do? How often do the users need to do that?

What do you need to tell the users so that they will

make that decision? Addressing the case study, we

have considered in this paper, because the

international students mostly always find ways for

circumventing the GFC. It would be more efficient

and exploitable in term of surveillance and

monitoring to provide an openly monitored channel

to the international students. Such a channel will

allow these users to access the content they need and

at the same time will enable a better surveillance of

the network traffic.

To sum up, like great constructions designed for

the good of mankind, whether surveillance or

circumvention, tools should be designed based on the

users need and context. The complexity of a given

security measure that only considers the

technological side of the system and fails to consider

the users during the design is breaking the weakest

link in the security chain.

REFERENCES

A. Dainotti, Kimberly C. Claffy, M. Russo , C.Squarcella,

Marco C., Antonio P. and Emile Aben. (2011). Analysis

of country-wide internet outages caused by Censorship

Proceeding IMC '11 Proceedings of the 2011 ACM

SIGCOMM conference on Internet measurement

conference, Pages 1-18 ISBN: 978-1-4503-1013-0

Arma. (2014). How to read our China usage graphs?

Retrieved in 2015, from https://blog.torproject.org/blog

ICISSP 2016 - 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

378

/how-to-read-our-china-usage-graphs

Chellappa, Ramnath K., and Raymond G. Sin. (2005)

“Personalization versus privacy: An empirical

examination of the online consumer’s dilemma."

Information Technology and Management 6.2-3: 181-

202.

Clayton, R., Murdoch, S. J. & Watson, R. N. M. (2006),

“Ignoring the great firewall of china”, in G. Danezis &

P. Golle, eds, ‘Privacy Enhancing Technologies

workshop (PET 2006)’, LNCS, Springer-Verlag.

CSC. (2013). China Scholarship Council Organized the

First CSC Scholarship Student Conference. Retrieved

in 2015, from http://en.csc.edu.cn/News/

db88603b8da54f89a574f863b6a1863b.shtml

CSC. (2015). Introduction to Chinese Government

Scholarships. Retrieved in 2015, from

http://www.csc.edu.cn/laihua/scholarshipdetailen.aspx

?cid=97&id=2070

Danezis, G. (2011). An anomaly-based censorship

detection system for Tor. The Tor Project.

Facebook. (2013). About Facebook's Security & Warning

Systems. Retrieved in 2015, from

http://www.facebook.com/help/365194763546571/

Facebook. (2015). En quoi consistent les notifications ou

alertes de connexion? Retrieved in 2015, from

https://www.facebook.com/help/www/162968940433

354

Guardian. (2011). China tightens great Firewall internet

control. Retrieved in 2015, from

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2012/dec/14/ch

ina-tightens-great-firewall-internet-control

Han, P. (2010). The Internet in China. Retrieved in 2015,

from http://english1.english.gov.cn/2010-06/08/con

tent_1622956_7.htm

Hu Zuliu and Khan Mohsin S. (1997). Why Is China

Growing So Fast? Economics issues 8, International

Monetary Fund. ISBN 1-55775-641-4; ISSN 1020-

5098

Kincaid, J. (2013). Mark Zuckerberg On Facebook's

Strategy For China. Retrieved in 2015, from

http://techcrunch.com/2010/10/16/mark-zuckerberg-

on-facebooks-strategy-for-china-and-his-wardrobe/

Mahmood, S. (2012, November). New privacy threats for

Facebook and Twitter users. In P2P, Parallel, Grid,

Cloud and Internet Computing (3PGCIC), 2012

Seventh International Conference on (pp. 164-169).

IEEE.

Michael Backes, Goran Doychev, Boris Kopf. (2013).

Preventing Side-Channel Leaks in Web Traffic: A

Formal Approach. NDSS

Rodriguez, G. (2013). Facebook's "One Billion" May be

Even Bigger Than You Think. Forbes. Retrieved in

2015, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/giovanni

rodriguez/2012/10/04/facebooks-one-billion-may-be-

even-bigger-than-you-think/

Spiekermann, Sarah, Jens Grossklags, and Bettina Berendt.

(2001) "E-privacy in 2nd generation E-commerce:

privacy preferences versus actual behavior."

Proceedings of the 3rd ACM conference on Electronic

Commerce. ACM.

Walton, Greg. (2001) China's golden shield: corporations

and the development of surveillance technology in the

People's Republic of China. Rights & Demcracy.

Xu, X., Mao, ZM and Halderman, JA, 2011, January

Internet censorship in China: (. Pp 133-142). “Where

does the filtering occur?” In Passive and Active

Measurement Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Yang, Guobin. (2003) “The Internet and civil society in

China: A preliminary assessment.” Journal of

Contemporary China 12.36: 453-475.

A Privacy Threat for Internet Users in Internet-censoring Countries

379