The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal

Documents by using Ontologies

Mar

´

ıa G. Buey

1

, Angel Luis Garrido

2

, Carlos Bobed

2

and Sergio Ilarri

2

1

InSynergy Consulting S.A., Madrid, Spain

2

IIS Department, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain

Keywords:

Information Extraction, Ontologies, Legal Documents.

Abstract:

In the legal field, it is a fact that a large number of documents are processed every day by management

companies with the purpose of extracting data that they consider most relevant in order to be stored in their

own databases. Despite technological advances, in many organizations, the task of examining these usually-

extensive documents for extracting just a few essential data is still performed manually by people, which is

expensive, time-consuming, and subject to human errors. Moreover, legal documents usually follow several

conventions in both structure and use of language, which, while not completely formal, can be exploited to

boost information extraction. In this work, we present an approach to obtain relevant information out from

these legal documents based on the use of ontologies to capture and take advantage of such structure and

language conventions. We have implemented our approach in a framework that allows to address different

types of documents with minimal effort. Within this framework, we have also regarded one frequent problem

that is found in this kind of documentation: the presence of overlapping elements, such as stamps or signatures,

which greatly hinders the extraction work over scanned documents. Experimental results show promising

results, showing the feasibility of our approach.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, in many organizations, the process of

identifying data from legal documents is still per-

formed manually by people who handle them. These

documents are usually quite extensive, and the most

important data to be identified are often few. The per-

son who is responsible for doing this process devotes

considerable time to read and to identify these data,

time that she/he could be spending on other more im-

portant tasks. Therefore, it would be very useful to

provide an automatic tool to perform this data extrac-

tion, helping to make the handling of the process of

legal documents more agile.

Legal documents follow several conventions in

both structure and use of language, which, despite not

being completely formal, can be exploited to improve

information extraction. Moreover, this kind of docu-

ments contains in many cases a considerable amount

of overlapping elements like stamps and signatures.

These elements are usually required to prove the au-

thenticity of the document, so they are hardly avoid-

able. Thus, all the legal documents in this context are

digitalized with these marks, which can greatly ham-

per the process of extracting information from them.

In this paper, we propose an approach for the de-

velopment of tools to extract specific data from exten-

sive legal documents in text format. The data extrac-

tion process is guided by the information stored into

a special type of ontology that contains the knowl-

edge about the structure of the different types of doc-

uments, as well as references to pertinent extracting

mechanisms. In this context, we have searched for

solutions in order to improve the recall and the pre-

cision of the software by minimizing the presence of

annoying overlapping elements in the document. Fi-

nally, we present an implementation of our approach,

the AIS

1

system, which has been integrated within

the commercial Content Relationship Management

(CRM) solution of InSynergy Consulting

2

, a well-

known IT company. Despite the fact that experimen-

tal dataset is composed of Spanish legal documents,

our approximation is generic enough to be applied to

documents in other languages.

1

AIS stands for An

´

alisis e Interpretaci

´

on Sem

´

antica

which translates into Analysis and Semantic Interpretation

2

http://www.isyc.com

438

Buey, M., Garrido, A., Bobed, C. and Ilarri, S.

The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal Documents by using Ontologies.

DOI: 10.5220/0005757204380445

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2016) - Volume 2, pages 438-445

ISBN: 978-989-758-172-4

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 de-

scribes the analysis of the structure and the content of

the legal documents studied in this work. Section 3

explains the methodology proposed for the data ex-

traction process. Section 4 discusses the preliminary

results of our first experiments with real documents.

Section 5 analyzes and describes the state of the art.

Finally, Section 6 provides our conclusions and future

work.

2 WORKING CONTEXT

In this work, we deal with certain types of legal docu-

ments: notarial acts, judicial acts, registry documents,

and private documents (Child, 1992). These docu-

ments are required to perform different formalities

and, therefore, the type of data that is necessary to

extract from them varies. Furthermore, while being

well categorized, their content structure is quite het-

erogeneous, ranging from very well structured doc-

uments (e.g., notarial acts) to almost free text docu-

ments (e.g., private agreements between individuals).

To study the typology of these legal documents,

we have applied the research lines of discourse analy-

sis exposed in (Moens et al., 1999), and we have clas-

sified legal documents into different types. We as-

sume that each of these types of legal documents has

an associated set of attributes and information about

the minimum data required to be found within them.

For example, the data to be extracted from a particular

type of document might be its title, its protocol num-

ber, and the place and date where it was signed. Be-

sides, information about different entities (e.g. peo-

ple) participating in that document might also be re-

quired to be extracted, which comprise entity’s at-

tributes that might not depend on the specific docu-

ment type (e.g., name, identification number, address,

...), as well as attributes that depend on both the doc-

ument type, and the section where the entity appears

(e.g, their role in the legal act, their relationships with

other appearing entities, ...).

The use of machine learning techniques is not rec-

ommended in these scenarios because it is the typical

closed domain with essential and available human in-

volvement (Sarawagi, 2008). The most suitable solu-

tion to overcome these problems is applying regular

expressions to identify the possible patterns, but the

extensive number of pages and the presence of a large

number of similar items does not help. Besides, we

have misspellings and truncated words due to scan-

ning failures, or because of the presence of overlap-

ping elements (e.g., watermarks or stamps).

Therefore, we needed something more powerful

than a collection of regular expressions in order to en-

hance our data extraction procedure.

3 SYSTEM OVERVIEW

In this section, we describe the approach that has been

developed to face the objective of extracting infor-

mation that is contained in legal documents. Briefly,

our system analyzes and extracts a set of specific data

from texts that are written in natural language. The

extraction process is guided by an ontology, which

stores information about the structure and the con-

tent of different types of documents to be processed.

Specifically, this ontology models two types of infor-

mation:

• Typology and structure of documents. The ontol-

ogy contains information about the types of doc-

uments, their properties to be extracted, and the

sections that shape them. Each of the sections

modeled in the ontology includes further informa-

tion about which properties have to be extracted

from them, and the entities that might/must be de-

tected within such sections.

• Entities and extraction methods. The ontology

contains information about which entities have to

be obtained from each section of a document, how

they should be processed (procedures to be called

to perform the data extraction), and how they re-

late to entities in other sections.

An example of the ontology can be appreciated in

Figure 1. This sample shows an excerpt of the on-

tology devoted to extract information from a type of

document. The elements in capital letters include ref-

erences to the extraction methods. This model makes

it possible to define a modular knowledge-guided ar-

chitecture, so new document types can be added dy-

namically to perform the data extraction.

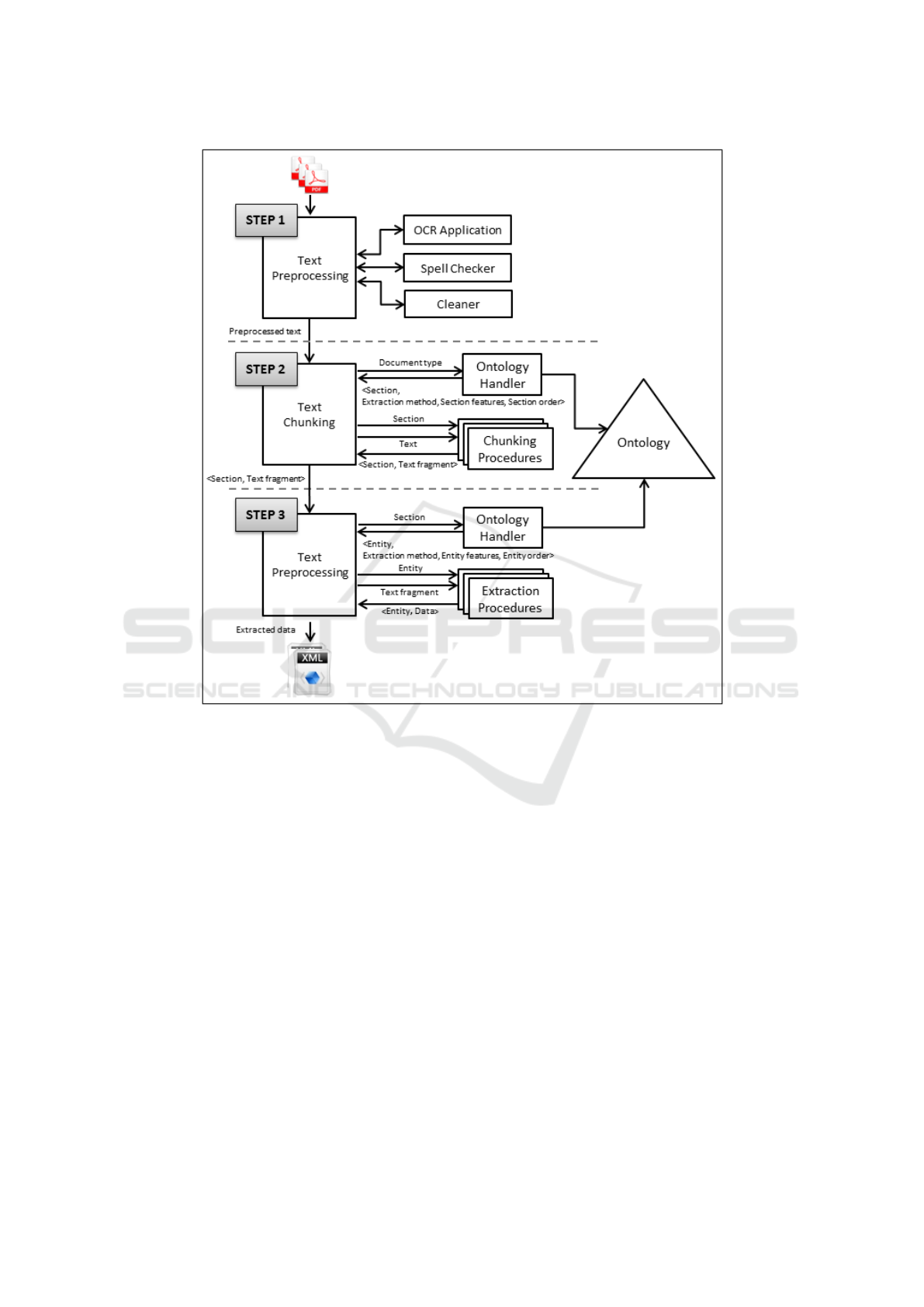

Figure 2 depicts our approach to data extraction,

which is divided into three main steps that our sys-

tem performs sequentially. We describe these steps

in more detail in the following subsections. The in-

put of the system consists of a set of legal documents

in PDF format with unstructured or semi-structured

information, and their type. All the documents have

been previously scanned and processed by an Opti-

cal Character Recognition (OCR) tool. The output is

a set of XML files with structured information about

the extracted data from each input text.

The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal Documents by using Ontologies

439

Figure 1: A partial sample of the ontology model.

3.1 Step 1: Text Preprocessing

As we can see in Figure 2, this step consists of dif-

ferent tasks that prepare texts before the extraction.

These PDF documents do not contain explicit text,

because they contain scanned images of physical doc-

uments. This is because the owner must keep the

original document and therefore he sends a scanned

document to the management company in charge of

the treatment. So, it is mandatory to apply an OCR

software to identify the text of the documents before

carrying on with the other tasks. Having obtained the

input text, our system uses two additional filters to

improve the quality of the input: the Spell Checker,

and the Cleaner (See Figure 2). The former deals

with correcting words that may appear misspelled or

truncated, while the latter is in charge of cleaning the

noise that the documents may contain, such as signa-

tures, stamps, page numbers, etc. These two steps are

needed because noise and misspelled words can hin-

der our task. To implement them in our prototype we

have used a pair of open source spell checkers: As-

pell

3

, and JOrtho

4

. They have different features and

performances, so we have combined them to get bet-

ter data quality. Regarding the OCR software, while

we consider it an external element, its effectiveness

will clearly influence the quality of our information

extraction.

For example

5

, if we have a document with the fol-

lowing scanned text:

3

http://aspell.net/

4

http://jortho.sourceforge.net/

5

For clarity’s sake, we show the examples in English,

even though AIS works with documents in Spanish.

”AB1234567 JOHN DAVIES NOTARY Fit Cestel-

lana, 1 Phone: 911234567 Fax: 911234567 28046

MADRID IINILATERAL MORTGAE. NUMBER

TWO THOIISAND SIX HUNBRED. In Madrid, on

June 15t, two thousand eleven.– - In front of me,

JOHN DAVIES, Notary of the Illus-[trious College

of Madrid with residence in this capital. APPEAR-

ING AS PART OF THE BORROWER AND THE

MORTGAGER: WILLIAM ROBERTS, of legal age,

single and a resident of MADRID (SPAIN), residing

in stret GRAN VIA, No. 31, and with 012345678G as

identification number...”

After the preprocess, we obtain:

”UNILATERAL MORTGAGE. NUMBER TWO

THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED. In Madrid, on June

15th, two thousand eleven. In front of me, JOHN

DAVIES, Notary of the Illustrious College of Madrid

with residence in this capital. APPEARING AS PART

OF THE BORROWER AND THE MORTGAGER:

WILLIAM ROBERTS, of legal age, single and a res-

ident of MADRID (SPAIN), residing in street GRAN

VIA, No. 31, and with 012345678G as identification

number...”

This is, the stamp numbers in the example

(”AB1234567 JOHN DAVIES NOTARY Fit Cestel-

lana, 1 Phone: 911234567 Fax: 911234567 28046

MADRID”) have been removed from the OCR input.

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

440

Figure 2: Steps of our approach to ontology-guided data extraction from legal documents.

3.2 Step 2: Text Chunking

After preprocessing the text, our system consults the

ontology to obtain the structure that it expects depend-

ing on the type of document (see Figure 2). With this

information, AIS identifies the different possible sec-

tions using methods for chunking and labeling texts,

and proceeds to analyze them. After that, for each

section, the system identifies the different entities and

their properties that may appear and participate in that

section (e.g., individuals, legal persons, etc.). This in-

formation is consulted during the processing of sec-

tions to know which extraction methods have to be

used for each entity to be detected in the text.

So, given the document and its type, the system

asks the Ontology handler to obtain information

about sections by querying the ontology. Specifically,

it returns a set of tuples (<Section, Extraction

method, Section features, Section order>)

with the following information:

1. Section: section type to be identified. It could also

be divided into subsections.

2. Extraction method: name of the extraction

method that the system has to invoke to detect the

section in the input text.

3. Section features: data related to the section that

is being processed. For example, its cardinality

(how many times it should appear in the text), mu-

tual exclusion with other section types (sections

that cannot appear in the same document of the

section), and so on.

4. Section order: order in which the sections should

appear. When processing semi-structured and

unstructured documents, we have introduced the

possibility of modeling information about the pro-

cessing order in the ontology.

After consulting this information, the system has a

number of methods to be called on the input text. Us-

ing the definition of the document features, our sys-

tem is able to detect whether the extraction has been

The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal Documents by using Ontologies

441

successful, providing warnings when it has been un-

able to find some particular expected fact. The re-

sult of this step is a set of tuples <Section, Text

fragment>.

Following the previous example, at this step we

obtain two different sections: the introduction and the

appearing. So, after this chunking process, we have:

<Introduction, UNILATERAL MORTGAGE NUMBER

TWO THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED. In Madrid, on

June 15th, two thousand eleven. In front

of me, JOHN DAVIES, Notary of the

Illustrious College of Madrid with

residence in this capital.>

<Appearing, APPEARING AS PART OF THE

BORROWER AND THE MORTGAGER: WILLIAM

ROBERTS, of legal age, single and a

resident of MADRID (SPAIN), residing in

street GRAN VIA, No. 31, and with

012345678G as identification number.>

3.3 Step 3: Section Processing

The final step (see Figure 2) is similar to the previous

one, but it manages different information. The input is

the set of tuples that the previous step returns, which

includes information about the sections and the text

associated to each of them. In this step, the system

consults the ontology to obtain which entities must be

identified in each Section, and it obtains another set

of tuples (<Entity, Extraction method, Entity

features, Entity order>), where:

1. Entity: a specific entity that the system has to de-

tect inside a determined section.

2. Extraction method: the method used to extract in-

formation about this particular entity.

3. Entity features: they contain information about

the properties of the entity to be extracted (sim-

ilar to the information considered for sections).

4. Entity order: order in which the entity should be

extracted.

After that, the system applies different methods

to identify these entities in each pair of <Section,

Text fragment>. This service-oriented approach

which we adopt allows us to integrate in the sys-

tem any extraction method dynamically, ranging from

custom made parsers based on easy rules (e.g., to de-

tect the presence of certain keywords), to more com-

plex ones (e.g., using complex rules or statistical ap-

proaches).

In general, we have a single method for each entity

to be identified that is responsible for trying to extract

as much information as it can about that entity (i.e.,

there will be documents that will only have the name

and ID of a person, while others will have also her/his

marital status and other attributes). All parameters

can be defined and the extraction method will always

try to take all of them. This process can be improved

when a Named Entity Recognizer (NER) (Nadeau

and Sekine, 2007) is used, so that their use is almost

mandatory to achieve optimal results in the process of

extracting information. Finally, note that whole sec-

tion where they appear could be exploited to further

detect and extract information about the relationships

that may occur between entities in the text, applying

rules or patterns to look for them in the extracted and

structured information.

Following the running example, the system

consults the ontology and learns that it has to obtain

the title, the protocol number, the location, the date,

and the notary’s name out from the Introduction

text; and the person, with each one of its properties

(name, address, or identification number) out from

the Appearing section. The system obtains exactly:

<Introduction,

<Title, UNILATERAL MORTGAGE>

<Protocol number, TWO THOUSAND SIX

HUNDRED>

<Location, Madrid>

<Date,June 15th, two thousand eleven>

<Notary’s name, JOHN DAVIES>>

<Appearing,

<Person,

<Name, WILLIAM >

<Surname, ROBERTS>

<Identification number, 012345678G>

<Marital state, single>

<Address, street GRAN VIA, No. 31>

<Location, Madrid>

<Country, Spain>>>

4 PRELIMINARY RESULTS

The data extraction process presented in this paper

has been incorporated into OnCustomer

6

, a commer-

cial Content Relationship Management (CRM) sys-

tem developed by InSynergy Consulting. The ontol-

ogy that is being used has 25 classes and 33 prop-

erties, and information about 2 chunking procedures

and 17 extraction methods. Regarding the NER tool,

we use Freeling

7

, a well known and widely used anal-

ysis tool suite that supports several analysis services

in both Spanish and English, as well other languages

which could be incorporated in our architecture in fu-

ture developments. The extraction methods used in

6

http://www.isyc.com/es/soluciones/oncustomer.html

7

http://nlp.lsi.upc.edu/freeling/

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

442

the experiments are mainly based on symbolic pat-

tern rules, due to the good performance empirically

obtained with this methodology over this type of doc-

uments.

To evaluate our current prototype, we used a sam-

ple of 144 Spanish notary acts. The extracted data

from this type of document can be grouped in two

different sets:

• Document Parameters (Doc-Param in Figure 3),

which are the data that are related to the docu-

ment itself. These parameters are the title of the

document, a protocol number given to the docu-

ment, the date and the location when and where

the document was signed, and the notary’s name.

• Person Parameters (Persons in Figure 3), which

corresponds to the data of the persons that are

mentioned in the document. These parameters are

name, surname, national identity number, marital

state, address, region, and country.

We assessed the performance of our approach us-

ing the well-known measures in the field of the Infor-

mation Extraction (precision, recall, and F-measure).

To calculate them, we took into account for each doc-

ument: the number of data to be extracted, the num-

ber of extracted data, and the number of data that have

been retrieved properly. The baseline was the appli-

cation of a set of extraction rules based on regular

expressions without using our ontology-based extrac-

tion approach and without using our document clean-

ing methods. The baseline results was not very good

because these documents were quite long (near one

hundred pages sometimes), and they were full of data

and names, so, the baseline method frequently re-

trieved too many results, most of them erroneous.

We performed two experiments (see results in Fig-

ure 3). The first one was measuring the effect of the

introduction of the use of the ontologies (Steps 2 and

3) to guide the extraction, leading to a substantial im-

provement of the process (Exp. 1). In the second

experiment (Exp. 2), we introduced the use of our

ad-hoc combination of the spell checkers mentioned

in section 3.1, and a text cleaner to eliminate iden-

tifiers, page numbers, stamps, etc. With these new

enhancements, our system achieved better results (a

F-measure above 80%). Of course, the rules to ex-

tract the data used were the same in all experiments

to isolate influences derived from its quality.

We have considered the set of Document Parame-

ters by averaging the results obtained for each of the

data (title, protocol number, etc.). Within this group

we get an average of 85% of precision and 78% of

recall. On the other hand, we have considered the set

of Persons by averaging the results obtained for each

of their attributes (name, address, etc.), and we have

obtained 93% of precision and 72% of recall. In Fig-

ure 3, Global is the mean of both results.

In the analyzed dataset, our proposed system ob-

tained an average of 89% of precision, and 75% of

recall in our data extraction system, which shows the

interest of this proposal. We have also analyzed the

erroneous results, and the system could be enhanced

by improving extraction algorithms, and by adjust-

ing the preliminary cleaning and correction processes.

We should continue exploring more types of docu-

ments, with more relationships and distinct entities;

but it seems clear that having knowledge to guide the

extraction has a very positive influence on this task

on such legal documents, and it facilitates the mainte-

nance labors and the amplifications of the system.

5 STATE OF THE ART

The use of ontologies in the field of Information Ex-

traction (Russell and Norvig, 1995) has increased in

the last years. An ontology is defined as a formal

and explicit specification of a shared conceptualiza-

tion (Gruber, 1993). Thanks to their expressiveness,

they are successfully used to model human knowl-

edge and to implement intelligent systems. Sys-

tems that are based on the use of ontologies for in-

formation extraction are called OBIE systems (On-

tology Based Information Extraction) (Wimalasuriya

and Dou, 2010). The use of an ontological model as a

guideline for the extraction of information from texts

has been successfully applied in other works as (Gar-

rido et al., 2012; Kara et al., 2012; Garrido et al.,

2013; Borobia et al., 2014).

Regarding legal issues, it is interesting to high-

light works such as History Assistant (Jackson et al.,

2003), which extracts rulings from court opinions and

retrieves relevant prior cases from a citator database.

It does all of this by combining natural language

processing techniques with statistical methods. An-

other system to classify fragments of normative texts

into provision types and to extract their arguments

was proposed by (Biagioli et al., 2005). That sys-

tem was based on multiclass Support Vector Ma-

chine classification techniques and on Natural Lan-

guage Processing techniques. More recently we find

TRUTHS (Cheng et al., 2009), a system developed

with a modified the classical Hobbs generic informa-

tion extraction architecture (Appelt et al., 1993) to ex-

tract information from criminal case documents and

to fill up a template.

The definition of extraction ontologies in the con-

text of the Semantic Web was made in (Embley and

The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal Documents by using Ontologies

443

Figure 3: F-measure results from the baseline, and from the experiments 1 and 2.

Zitzelberger, 2010). These conceptual models store

linguistic information for creating canonical annota-

tions that can be used for data storage or query in-

terpretation. In our case, we have created a modular

ontology model, containing on the one hand the lin-

guistic information and the structure of each type of

document, and on the other hand the knowledge of

what to do for extracting data in each part of the doc-

ument, expressed by complex methods more powerful

than regular expressions.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no

other works specially dedicated to the extraction of

data on legal documents in Spanish, taking into ac-

count the special difficulties in processing this lan-

guage (Aguado de Cea et al., 2008; Carrasco and

Gelbukh, 2003), for example: Spanish words contain

much more grammatical and semantic information

than the English words, the subject can be omitted

in many cases, and verb forms carry implicit conjuga-

tion, without additional words. Besides, it is hard to

locate information about extraction systems equipped

with robust methods of extracting in the presence of

OCR problems due to overlapping marks, but we have

found that it is a required task for achieving good re-

sults when working on this type of documentation.

Furthermore, the big difference between these afore-

mentioned works and ours is that we are capturing in

the ontology both the nature of the entities and the

formal structure of documents in order to boost the

extraction process.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Legal documents, such as notarial acts, judicial acts,

or registration documents, are often extensive and the

relevant data to be identified for most of the document

management tasks are often few. Besides, the identi-

fication of these data is still handmade by people in

many organizations. In this paper, we have presented

an approach to carry out an automatic data extraction

from such legal documents. Our extraction process is

guided by the modeled knowledge about the structure

and content of legal documents. This knowledge is

captured in an ontology, which also incorporates in-

formation about the extraction methods to be applied

in each section of the document. The service-oriented

architecture approach we have adopted makes our ap-

proach flexible enough to incorporate different tech-

niques to perform data extraction (via invoked meth-

ods). Finally, the preliminary experiments we have

carried out suggest that exploiting knowledge to guide

the extraction process improves the quality of the re-

sults obtained.

There are several lines of development as future

work. An interesting point is to adapt and expand the

notion of extraction ontologies within our approach.

Moreover, we also want to improve the efficiency of

our approach by using complex rules and statistical

approaches to enrich our extraction methods.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research work has been supported by the CICYT

project TIN2013-46238-C4-4-R, and DGA-FSE. The

authors also thank InSynergy Consulting for their

support and provided framework.

REFERENCES

Aguado de Cea, G., Puch, J., and Ramos, J. (2008). Tag-

ging Spanish texts: The problem of ’se’. In 6th In-

ternational Conference on Language Resources and

Evaluation (LREC’08), pages 2321–2324.

ICAART 2016 - 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

444

Appelt, D. E., Hobbs, J. R., Bear, J., Israel, D., and Tyson,

M. (1993). Fastus: A finite-state processor for infor-

mation extraction from real-world text. In 13th Inter-

national Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence

(IJCAI’93), volume 93, pages 1172–1178.

Biagioli, C., Francesconi, E., Passerini, A., Montemagni,

S., and Soria, C. (2005). Automatic semantics ex-

traction in law documents. In 10th International Con-

ference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (ICAIL’05),

pages 133–140.

Borobia, J. R., Bobed, C., Garrido, A. L., and Mena, E.

(2014). SIWAM: Using social data to semantically

assess the difficulties in mountain activities. In 10th

International Conference on Web Information Systems

and Technologies (WEBIST’14), pages 41–48.

Carrasco, R. and Gelbukh, A. (2003). Evaluation of TnT

Tagger for Spanish. In 4th Mexican International

Conference on Computer Science (ENC’03), pages

18–25.

Cheng, T. T., Cua, J. L., Tan, M. D., Yao, K. G., and Roxas,

R. E. (2009). Information extraction from legal doc-

uments. In 8th International Symposium on Natural

Language Processing (SNLP’09), pages 157–162.

Child, B. (1992). Drafting legal documents: Principles and

practices. West Academic.

Embley, D. W. and Zitzelberger, A. (2010). Theoretical

foundations for enabling a web of knowledge. In 6th

International Symposium on Foundations of Informa-

tion and Knowledge Systems (FoIKS’10), pages 211–

229.

Garrido, A. L., Buey, M. G., Ilarri, S., and Mena, E. (2013).

GEO-NASS: A semantic tagging experience from ge-

ographical data on the media. In 17th East-European

Conference on Advances in Databases and Informa-

tion Systems (ADBIS’13), pages 56–69.

Garrido, A. L., G

´

omez, O., Ilarri, S., and Mena, E. (2012).

An experience developing a semantic annotation sys-

tem in a media group. In 17th International Confer-

ence on Applications of Natural Language Processing

to Information Systems (NLDB’12), pages 333–338.

Gruber, T. R. (1993). A translation approach to portable

ontology specifications. Knowledge acquisition,

5(2):199–220.

Jackson, P., Al-Kofahi, K., Tyrrell, A., and Vachher,

A. (2003). Information extraction from case law

and retrieval of prior cases. Artificial Intelligence,

150(1):239–290.

Kara, S., Alan,

¨

O., Sabuncu, O., Akpınar, S., Cicekli, N. K.,

and Alpaslan, F. N. (2012). An ontology-based re-

trieval system using semantic indexing. Information

Systems, 37(4):294–305.

Moens, M.-F., Uyttendaele, C., and Dumortier, J. (1999).

Information extraction from legal texts: the poten-

tial of discourse analysis. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 51(6):1155–1171.

Nadeau, D. and Sekine, S. (2007). A survey of named entity

recognition and classification. Lingvisticae Investiga-

tiones, 30(1):3–26.

Russell, S. and Norvig, P. (1995). Artificial intelligence:

a modern approach. Prentice-Hall Series in Artificial

Intelligence.

Sarawagi, S. (2008). Information extraction. Foundations

and trends in databases, 1(3):261–377.

Wimalasuriya, D. C. and Dou, D. (2010). Ontology-based

information extraction: An introduction and a survey

of current approaches. Journal of Information Sci-

ence, 36(3):306–323.

The AIS Project: Boosting Information Extraction from Legal Documents by using Ontologies

445