The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by

Primary School Teachers

Elena Codreanu

1,2,3,4

, Christine Michel

1,3

, Marc-Eric Bobillier-Chaumon

1,2

and Olivier Vigneau

4

1

Université de Lyon, Lyon, France

2

Université Lyon2, GRePS, EA 4163, Bron, France

3

INSA-Lyon, LIRIS, UMR5205, F-69621, Villeurbanne, France

4

WebServices pour l’Education, Paris, France

Keywords: VLE, Acceptance, Activity Theory, Primary School, Professional Practices.

Abstract: This article presents a study on the conditions of use of a VLE (Virtual Learning Environment) by primary

school teachers. To this end, we used research related to activity theory and implemented qualitative

methods (individual and collective interviews). Our study describes how teachers (8 participants) perceived

the role of the VLE in the evolution of their working practices (maintaining, transforming or restricting

existent practices), in their relationship with parents and in the follow-up of their students.

1 INTRODUCTION

The definition of Virtual Learning Environments

differs from country to country. In UK, the VLEs

were designed mainly as pedagogical and

collaborative and lately there were added school

management tools. In this view, a VLE is “learner

centred and facilitates the offering of active learning

opportunities, including specific tutor guidance,

granularity of group working by tutor and learners”

(Stiles, 2000). By contrast, in France, the VLEs were

since the beginning designed as a unique access

workspace, both for school management and for

learning activities. The initially management

modules (marks, absences) designed for virtual

classrooms served then to design pedagogical

applications and collaborative group works. In both

British and French systems, VLEs aim to encourage

communication and collaborative practices between

the members of a school community through tools –

such as blogging and a messaging service – and to

foster access to information (in regards to

homework, for example) through the use of a digital

planner.

The last report of OECD (Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development) mentions

that technologies are not sufficient to support

teaching and instructional purposes. They are simple

tools in the hands of teachers and it depends on them

to take good use in their activities. Yet, our society

is “not yet good enough at the kind of pedagogies

that make the most of technologies (…). Adding 21st

century technologies to 20th-century teaching

practices will just dilute the effectiveness of

teaching” (OECD, 2015, p. 3). This is the reason

why we choose to analyse the technology acceptance

of teachers and the practices they develop.

2 TEACHERS’ VLE

ACCEPTANCE STUDIES

Some studies analyse the teachers’ attitudes to and

beliefs about this type of technology. In their study,

Kolias et al. (2005) examined attitudes and beliefs of

teachers from Finland, Greece, Italy and the

Netherlands after a first teaching experience with a

computer learning environment in order to see if

they would be able to include technology in their

everyday practices. The study gives very promising

conclusion about the possible use of technology, but

miss of real practice and acceptance observations.

Others studies analyse the teachers practices and

the problems linked with the VLE uses. Indeed, the

VLEs have been mainly used in secondary education

and higher education. French studies showed that

Codreanu, E., Michel, C., Bobillier-Chaumon, M-E. and Vigneau, O.

The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by Primary School Teachers.

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 299-307

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

299

certain teachers had partly integrated VLEs in their

professional practices. Prieur and Steck (2011)

indicated that, although teachers recognized the

pedagogical benefits of VLEs, they were not ready

to endorse them due to poor ergonomics, and to their

lack of training and proficiency in IT tools. Teachers

also felt overworked and resisted the idea of

extending the “school space-time continuum”

outside of school. For their part, Poyet and Genevois

(2010) identified differences in culture: since VLEs

are often seen as management tools for businesses,

they may need to be “translated” and the meaning

adapted to the context of school. One of the ways to

solve this issue would be to use school-based

metaphors (“notebooks”, “lockers”) instead of

bureaucratic terms (“messaging”, “agenda”). Poyet

and Genevois showed how VLE tools were

unfamiliar to teachers and how the latter did not

fully grasp their pedagogical uses and benefits. This

led to unsatisfying experimental phases in which

teachers tested the tool's various functions, “without

always having a full representation of the tool's

potentialities and specific limits”. This drew

teachers to prefer using personal and familiar tools

(such as their own emails). Similar observations

were made by Pacurar and Abbas (2014) who

noticed that the VLE was perceived as a

communication tool (through the messaging service)

and an administrative tool (assigning grades, writing

down absences), but that it “was not firmly anchored

in pedagogical practices”, especially when it came

to using it during class time or to design class

material. The prescribed uses did not answer the real

needs felt by teachers on a daily basis. These

conclusions are also given by Firmin and Genesi,

(2013) and Blin and Munro (2008). Bruillard (2011)

mentioned the complexities in deploying VLEs

when a variety of people are involved: teachers,

parents, students, school districts, local authorities,

software publishers and the Ministry of Education.

Bruillard also noticed a paradox between the

Ministry's will to open schools up to parents, and the

actual low amount of parental implication. Teachers

are also concerned that parents may interfere in their

pedagogical choices. These difficulties are further

amplified by the fact that teachers who use VLEs do

not get institutional recognition. Practitioners in the

field have also felt disempowered since external

companies were called to design the VLEs. There is

also the risk of creating inequalities or even to

exclude certain parents who are less equipped and

trained in digital technologies. Missonier (2008)

developed these points based on the design and the

deployment of VLE projects that were managed by

local authorities and service providers. These

approaches have not always been very effective,

since they depend on the project manager – who

may lack in transparency or carefulness – to solve

disputes linked to functionalities or uses. This, in

turn, leads to different protagonists within the

network to decrease their commitment. Prieur and

Steck (2011) recommend implementing spaces for

ideas “that articulate the current practices of

teachers, practices that can help foster the

acquisition of skills and the potentialities of different

VLE tools, in order to develop possible

instrumentalisations”. This would help to adapt

prescribed uses, depending on the context.

Voulgre (2011) introduced a political dimension.

Teachers are generally favourable to arguments

promoting the uses of VLEs: the latter are useful to

catch up on classes (illness, loss of grades), to

retrieve previous work or to support students with

schooling difficulties. But the fact that not all

children have Internet at home represents an

inequality, thus preventing teachers from fully using

VLEs. Such a refusal is seen as a “type of counter-

power” against political injunctions. On the

contrary, acceptance factors are linked to the respect

of hierarchy, of the institution and of the law

(obligation to use a VLE); other positive factors are

linked to the values of solidarity and cooperation

that are promoted by VLE tools.

Other studies also point out the importance of

technical infrastructure: access to the computer

classroom, number of computers in classrooms,

Internet access, broadband speed and technical

support. The school institution’s management, the

organisational culture and VLE implementation

strategies have all a great role in technology

acceptance (Keller, 2006; Keller; 2009; Osika,

Johnson and Buteau 2009; Babic, 2012). Finally,

lack of competences in technology, lack of

confidence and lack of time were mentioned

(Karasavvidis, 2009). In the end, all of these studies

showed that the acceptance of VLEs by teachers

depended on practical considerations, as well as

strategic concerns that were both professional and

political.

VLE began to be deployed now in primary

schools. Only a few studies explored the acceptance

of VLE in these contexts. Berry (2005) highlighted

that primary school pupils can use VLEs and

appreciate it in case of absence because they can

easily get lesson content and homework. Moreover,

they have more confidence to discuss mathematics

problems on the VLE platform. But younger

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

300

children differ greatly from students in secondary or

higher education in terms of their autonomy and

their use of digital media. So we are led to ask

ourselves how primary school teachers take this

factor into account and more generally how they

include such a new tool in their professional

practices: are they able to adapt or develop their

practices or not and what are their reasons?

We need to evaluate how actual teaching

practices can evolve in order to integrate and make

profit of the existing technologies. This is why we

aimed in this field study to identify the current

teaching practices that constitute the core of

professional activities for primary school teachers.

We also wanted to identify tensions that could lead

us to find ways to improve the design of VLEs and

to provide recommendations for uses and services.

3 ANALYSING ACCEPTANCE

3.1 Acceptance Models

In Davis's (Davis, 1989) Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM), certain requirements like perceived

usefulness and perceived ease of use are ill-adapted

to improve the design and the implementation of a

system, to describe actual practices at work and so to

study the eligibility of educational platforms.

Indeed, the TAM has methodological shortcomings

(its factor-structure is not systematically replicated,

the questionnaire is the only assessment method

used) and it is out of line with the educational

environment. The TAM is a predictive and

deterministic model which is limited to individual

socio-cognitive factors and which does not take into

account the specific context of using the technology

in the educational sector. This context includes

elements such as a regulatory environment, a school

curriculum, relationships with families, and

professional practices and histories. The activity

theory can help to understand the act of teaching in

all its complexity.

3.2 Activity Theory

Activity theory, as detailed by Engeström, Miettinen

and Punamaki (1999) and Kuutti (1996), provides

more complete elements to quantify the context of

use. Instead of referring to uses, activity theory

refers to an activity system: the user (subject) has a

precise objective and accomplishes it by using

certain instruments (tools). He/she fits into a social

community (the group of people who intervene in

the activity). This community is regulated by certain

operating rules (the norms and rules to respect in a

given activity), and respects specific divisions of

work (the ways in which roles are distributed among

individuals).

Activity systems are characterized by

contradictions (or internal tensions), which favour

and trigger innovation; such changes contribute to

further development. Therefore, activity theory

appears to be useful to qualify the context as well as

to define the dynamics at work when accepting and

taking ownership of technology.

3.3 The Teacher’s Activity System

The teacher’s activity system is summarized in

figure 1 and relates to the educator’s daily practices.

These practices occur with or without instruments,

since they often take the shape of direct

communication in class, and can be supplemented

with instruments such as the board, posters,

notebooks, etc. These practices follow rules that are

specific to the educational system and fit into an

educational community composed of teachers,

students and parents. The division of work includes

the effective practices inherent to the profession and

the ways in which the different tasks are distributed

among the different protagonists. In terms of the

education and follow-up of students, teachers and

parents work together, but in different contexts.

Each group’s responsibility is therefore well defined.

With the arrival of a new technological tool, used

both in class and at home, these differentiated roles

and identities may come into conflict.

Figure 1: Activity system (Engeström, Miettinen and

Punamaki, 1999).

Furthermore, according to Rabardel and

Bourmaud (2003), the conditions needed to

implement human-machine interactions lead to the

modification of the technology's properties and,

consequently, to the readjustment of human

conducts. This occurs through the process known by

Rabardel and Bourmaud as the instrumental genesis

The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by Primary School Teachers

301

(a double process of instrumentation/

instrumentalisation). The tool therefore does not

only exist for itself or in an isolated way. It is

socially embedded and fits within certain practices,

habits and social communities that guide its use and

transform its characteristics. This theoretical

perspective therefore leads us to consider acceptance

as being situated, meaning that it is constructed in

and by the activity (Bobillier-Chaumon, 2013).

Like Kolias et al. (2005) we choose using the

activity theory to detect VLE acceptance and non-

acceptance factors according to contexts of use. The

standards considered to define acceptance are linked

to the ways in which the profession is practiced, to

social and work constructs and to ways in which the

VLE tool is used and deployed.

4 FIELD STUDY

METHODOLOGY

The approach developed in this study is essentially

qualitative. We aimed to collect testimonies from

teachers in which they represented and perceived

their experiences as they teached with and used a

VLE.

4.1 Observed Context and Participants

All participants in our study were part of the

Versailles and Caen school districts (situated near

Paris). 6 schools were in the Versailles district and 6

were in the Caen district. They volunteered to

experiment with the VLE One for 2 years. At the

time of our study, 26 teachers (in both districts) had

volunteered to be part of the experiment and had

already used the VLE One for 3 to 6 months.

We questioned 8 teachers over the course of 4

individual interviews and 2 group interviews (with 2

teachers in each interview). Among the teachers, two

were school principals who were also giving classes

(in first and fifth grades). The other teachers worked

in first grade (2), second grade (1) and fifth grade (3)

classes. The group of participants was composed of

seven women and one man. The schools were all

situated in urban areas, in the Versailles school

district (6) and in the Caen district (2). The average

age of participants was of 46 years with a standard

deviation of 15.

4.2 Description of the Tool

The VLE used in this study is entitled One. It was

specifically designed for an elementary school

audience, with ergonomics and interfaces that are

suitable for children (Budiu and Nielsen, 2010,

Lueder and Rice 2007). The One interface is

therefore simple, intuitive and attractive (see Figure

2). The collaboration functions that are offered

consist in a Messaging Service, a Blog and a Storage

Space. One also offers customization features (My

Account, My Mood), notifications (a News Feed,

birthday notifications), organizational tools

(Calendar) and a school website. Each user has the

option of customizing his/her profile with a picture

and personal information (motto, mood, information

on favourite leisure activities, films, music, food).

Students are by default included in their class group

and have access to the content published in the

group by the teacher.

When we were conducting our study, the VLE

One had not yet offered services such as the Planner

notebook and the Multimedia notebook.

Figure 2: Interfaces for the pages « News Feed » « The Classroom » and « My Apps » in the VLE One.

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

302

4.3 Data Collection

Teachers participated to semi-structured interviews.

These interviews lasted an hour and a half on average

and tackled the following themes: the teachers'

experience with TEL (Technology Enhanced

Learning), the school's computer equipment, the

teacher’s representation of the VLE, needs related to

the VLE, the VLE's usefulness, ease of use and

intentions of use, difficulties of use, and the

implications of the VLE for the teaching profession.

Teachers could speak openly and were able to give

their critical point of view on various uses, share their

own representations of the tool, and give their opinion

on functions that were being developed, such as the

planner notebook, the digital parent-teacher notebook

and the multimedia notebook. They were also

welcome to recount difficulties linked to the use of

the VLE, using Flanagan's critical incident technique

(Flanagan, 1954).

4.4 Analysing the Teachers’ Interviews

The interviews were entirely recorded and

transcribed so that they could be systematically

studied (Bardin, 1996). We considered in our

analysis the comments that associated One with

daily teaching practices, operating rules (linked to

the educational system), the education community

(composed of teachers, students and parents) and the

division of work (the ways in which tasks are shared

between different groups of people). We used the

sentence – a basic syntactic unit built around a verb

– as the main unit to study the transcripts. Sentences

were identified as in the following example: “I

showed them how to make folders (sentence 1)/, but

it is hard for the students (sentence 2)”. We also

distinguished between the comments that were

rather favourable (supporting initiatives) and the

ones that were less favourable (difficulties in use).

We proceeded to do counts and percentage

calculations to rank the different factors. We

determined that the users had accepted the VLE

when they mentioned the successful ways in which

they used it, the adjustments they made or the

contradictions they encountered and overcame.

Categories weren't pre-established and we retained the

themes that had been mentioned at least three times.

5 RESULTS

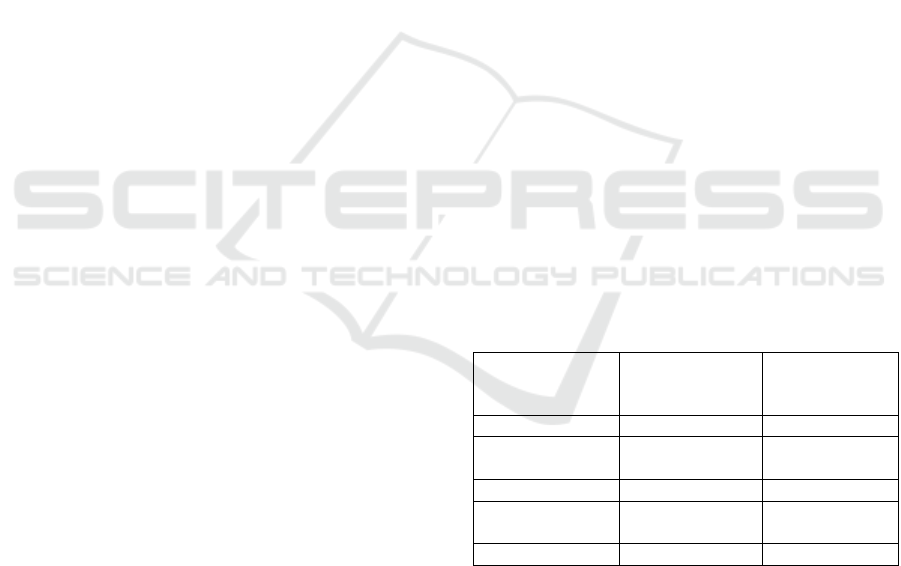

The analysis revealed 4 main themes (see Table 1),

as well as 16 sub-factors (see Table 2): (1) factors

linked to the practice of the profession (the

workload, raising awareness of digital uses and

habits, work recognition), (2) factors linked to

pedagogical monitoring (pedagogy, health and

safety, emotions and attractiveness); (3) factors

linked to social and work-related organization

(collaboration, communication, the reorganization of

communicative practices), (4) factors linked to the

tool's use and deployment (ease of use, usefulness,

feedback, computer and network equipment, support

and assistance). We will first present the results that

stemmed from the four main factors; we will then

proceed to describe the sub-factors.

5.1 Main Factors

In Table 1, we can see that the factors linked to

social organization brought about the largest number

of positive comments (88), which means that the

VLE played an important role in communication and

collaboration practices within the school activity

system. Conversely, factors linked to the teaching

profession and to the use and deployment of the

VLE gathered the largest number of negative

comments. The deployment and use of the VLE

therefore seem to raise questions linked to

professional recognition and to the practice of the

teaching profession. It also raises issues regarding

the alignment of VLEs with school uses and habits.

In the following paragraph, we present an analysis

according to each sub-factor (see Table 2), thus

allowing us to refine each element.

Table 1: Main Factor Occurrences.

Factor Number of positive

comments

Number of

negative

comments

Profession 35(15,56%) 90 (36%)

Pedagogical

follow-up

54(24%) 57 (22,8%)

Social organisation 88(39,11%) 14 (5,6%)

The tool’s use and

deployment

48(21,33%) 89 (35,6%)

Total 225(100%) 250 (100%)

5.2 Factors Linked to the Practice of

the Profession

As we can see in Table 2, the perceived workload

(triggered by the use of the VLE) brought about the

largest number of negative comments (72). In fact,

teachers had the impression that they needed to

invest additional time to master the VLE's

functionalities and to imagine interesting projects to

do on the platform. They also felt that using the VLE

The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by Primary School Teachers

303

implied sustained and continuous work for new tasks

that did not necessarily fit into their areas of

expertise, such as: taking pictures, downloading

material on the computer and then on the VLE,

publishing blog posts, writing messages, and

designing teaching projects that included the VLE.

Since these teachers did not have a dedicated time

slot to use these technologies, they had to use

pedagogical time to become familiar with such tools.

Teachers also felt the weight of large workloads,

with the impression of having an ever increasing

amount of informational solicitations. The VLE had

indeed been added to a number of pre-existing

educational platforms: academic e-mail, the career

management platform “I-prof”, online training

platforms, didactic platforms and an online

handbook of skills. Teachers therefore felt

constantly submerged by a large amount of data

which they had to manage (email addresses,

different login names and passwords for each

platform, various approaches and functions

according to the different resources...). They also felt

overwhelmed by the informational content that they

had to focus on and prioritize (academic

information, pedagogical information, event

notifications to sort and share...). Faced with the fear

of having to work twice the amount with a VLE,

some teachers refused to publish their lessons on the

VLE since they already did the same thing using

their own automation tools: “I already create the

lesson on “paper board”, so putting it up again (on

the VLE)... I do not want to do that...”

Teachers made 20 positive comments about

making students more responsible when using

digital tools. Teachers found that they had a part to

play when training “students to use digital tools

responsibly”. On the other hand, some teachers

found that parents should be in charge of raising

their children's digital awareness (12 comments).

These teachers' main arguments had to do with the

fact that working on the students’ digital

responsibilities affected other teaching activities

negatively. They also argued that such digital tools

were massively consulted by the children at home,

such as when they checked new messages. For these

reasons, controlling digital tools should relate to the

private sphere. This opinion was not necessarily

shared by parents who believed that, on the contrary,

the follow-up on digital practices should be done by

the institutions that set up the tools in the first place.

We can therefore see that, within the “school-home”

axis, responsibilities and roles between teachers and

parents may need to be redefined within the teaching

program, and the division of work would need to be

more efficiently coordinated (controlling and

following up on uses).

Work recognition was mentioned positively 15

times. Some teachers saw the VLE as a way to

highlight classroom work through the blog. Some

activities, which had previously been almost

invisible to parents, could now be displayed, such as

sporting activities, class outings, and the work of the

pupils themselves. The VLE then became a tool that

could help recognize the teacher’s and the students’

work. But such recognition is still limited due to

parents not being fully involved in the VLE project

and not consulting these resources often (negative

mentions).

5.3 Factors Linked to Student

Monitoring

According to the teachers, the primary benefit of

VLEs for students lied in the fact that VLEs helped

to build a more attractive and stimulating

relationship based on emotions (30 positive

comments in Table 2). The VLE was a motivating

tool for students and allowed them to appreciate

class work. In terms of pedagogy, the VLE was seen

as a benefit (20 positive comments) in the

construction of verbal expression and student

communication. It was also positively viewed to

raise awareness and autonomy when students were

working with computers. The VLE blogs were

therefore often co-edited by the teachers and the

students.

However, teachers also expressed many fears

linked to the children’s health and safety (57

negative comments versus 4 positive ones). These

fears related more specifically to possible abuses

(bullying, insults) or to the misuse of

communication and coordination tools. Teachers did

not gave any access to the children's accounts and

were therefore unable to control the content of

exchanged messages. Several teachers created a

fictitious student account to follow and control

exchanges. This also allowed them to check the

layout quality of the information and documents that

they published on the VLE. We noticed that the

teachers who had not used the platform in such an

innovative way weren't as satisfied with the device.

This example highlights the importance of offering

verification and surveillance functionalities for the

teachers, with parent or student views available.

Another fear related to ways in which the children

themselves could use the VLE in transgressive ways.

It is particularly difficult for teachers to authenticate

information coming from the system, as the

following example shows: “I received a parental

message, I do not know if it was the older brother or

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

304

the parent who sent the message.../... so I needed to

go back to the paper notepad to write a note.../... on

the notepad, there's the handwriting, the signature,

we can quickly tell the difference between a parent

and a child”.

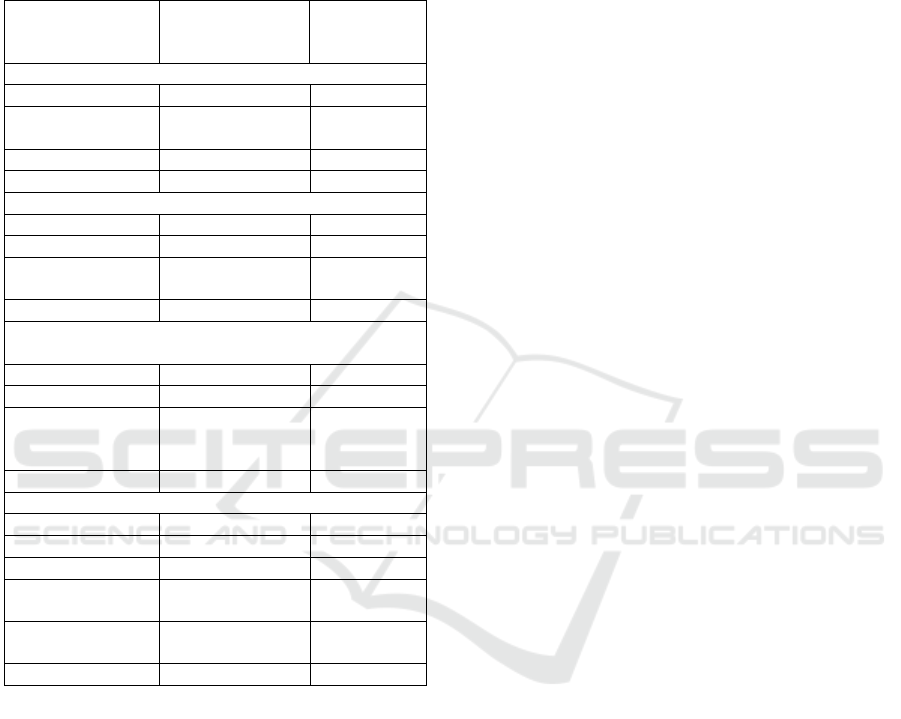

Table 2: Sub-factor Occurrences.

Sub-factor

Number of

positive

comments

Number of

negative

comments

Factors linked to the practice of the profession

Workload 0 (0%) 72 (28,8%)

Raising awareness

on digital uses

20 (8,89%) 12 (4,8%)

Work recognition 15 (6,67%) 15 (6%)

Total

35 (15,56%) 90 (36%)

Factors linked to student monitoring

Pedagogy 20 (8,89%) 0 (0%)

Health and safety 4 (1,78%) 57 (22,8%)

Emotions and

attractiveness

30 (13,3%) 0 (0%)

Total

54 (24%) 57 (22,8%)

Factors linked to social and work-related

organization

Collaboration 12 (5,33%) 0 (0%)

Communication 72 (32%) 8 (3,2%)

Reorganizing

communicative

practices

4 (1,78%) 6 (2,4%)

Total

88 (39,11%) 14 (5,6%)

Factors linked to the tool’s use and deployment

Ease of use 27 (12%) 24 (9,6%)

Usefulness 9 (4%) 6 (2,4%)

User feedback 4 (1,78%) 39 (15,6%)

Computer and

network equipment

0 (0%) 6 (2,4%)

Support and

assistance

8 (3,56%) 14 (5,6%)

Total

48 (21,33%) 89 (35,6%)

5.4 Factors Linked to Social and

Work-related Organization

VLEs were particularly appreciated as a tool

supporting communication (72 positive comments).

Certain teachers, who created blogs, mentioned

these blogs in the notepads when information needed

to be consulted. Teachers seemed to appreciate the

positive role that the VLE played in teacher

collaboration (12 mentions). Sharing resources made

it easier to organize common activities and outings,

and facilitated pedagogical work.

Negative comments (8) addressed the messaging

service as a communication method, highlighting the

fact that this service did not distinguish between in-

school time and out-of-school time. Teachers

mentioned the need to change the settings so that

parents could only send messages outside of school

time and to limit school-time messages between

students. Concerning the parents, such parameters

would limit the amount of last-minute intrusive

messages that require additional work on the

teacher's behalf during class time. Teachers have

more control using the parent-teacher notepad.

Providing these settings could be useful as a first

step. It would reassure teachers and would give them

time to set-up digital awareness activities for

students and parents.

5.5 Factors Linked to the Tool’s Use

and Deployment

Teachers reported finding the platform user-friendly

(27 positive comments). They considered the

functionalities and information coherent and easily

accessible through the menu and the icons. The

negative comments (24) were linked to the

functionalities in the VLE's Document space:

teachers would have liked to share folders rather

than files: “the children receive... [the files] just like

that. It is not easy for them, we have a Shared

Document and everything is mixed together: music,

stories. If the name of the folder is a bit vague, they

will not know”. There was also a lack of visibility as

to who consulted content and who connected to the

platform. By following the news feed, teachers

managed to see the activity of other users (parents,

students), but only if the latter had modified a

certain feature, such as their avatar or their motto.

But feedback could not be retrieved when users

simply consulted the platform without leaving

tangible traces. “It is true that... if they do not

change their mood or their motto, we do not know if

they have connected or not. It would be interesting

for us users to know who saw the content”. In order

to obtain such data, teachers had to do an additional

task which consisted in sending a questionnaire

through the parent-teacher notepad or by asking the

students if their parents had connected to the

platform. Such feedback was important in order to

build ties with the different educational partners and

to make sure that the published information had

actually been seen and received. Otherwise, teachers

had difficulties knowing if the system was really

useful and effective.

The lack of computer infrastructure (equipment,

networks...) was also seen as hampering the

acceptance of VLEs (6 comments). Teachers would

have liked to use the VLE in class with the students

but they did not have enough computers and tablets.

“we would almost need to have computers in the

class all the time to really use (VLEs) in every day

The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by Primary School Teachers

305

teaching”. Teachers also pointed out that all students

did not have equal access to VLEs: some had

continuous access, while others had restricted access

through their parents; some students did not have

Internet access at all. Finally, teachers mentioned a

lack of support and assistance. They did not feel

adequately trained to use VLEs. Given the fact that

this was an experimental implementation phase, not

all possible means were used to support the teachers.

On the long term, academic supervisors would need

to get involved in training and supporting teachers.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

We noticed that, in terms of acceptance, the uses of

the VLE spurred tensions that were similar to the

ones described by Prieur and Steck (2011) and

Voulgre (2011) in secondary education. We

observed contradictions between the artefact, the

community and the rules as well as contradictions

between the artefact and the division of work. The

first type of contradiction was linked to the

subverted uses of the Messaging Service or the

News Feed. There was also a lack of digital access

due to poor infrastructure in schools and in some

homes. The second type of contradiction was due to

an excessive workload and an increase in the

teachers’ professional responsibilities through the

extension of the “school space-time continuum”. We

recommend that decision-makers (the Ministry,

school districts) provide better information on VLE

users’ responsibilities. When it comes to

community uses – such as the ways in which to use

the messaging service or whether or not use

feedback indicators– we think that such decisions

can be made at a local level through discussions

between the school administration, the teachers and

the VLE publisher. Depending on contexts and

practices, certain modes of operation may or may

not be effective or acceptable.

There were fewer contradictions linked to the

artefact itself. Teachers appreciated the services

offered by One as well as its ergonomics; they tried

to adapt the VLE to their professional practices.

They did not hesitate to make requests to improve

the tool. They also agreed to help train children and

their parents on digital best practices. Teachers

showed signs of acceptance in this area, but they still

need to be given more support and assistance to

maintain such uses on the long term.

To conclude, the acceptance of this VLE seems

to have been overall positive since One was well

designed and relatively adapted to the practices of

the teachers involved. The main problems are linked

to the ways in which the tool is implemented. The

recommendations formulated here are meant for the

Ministry of Education and school principals.

Clarifications need to be made concerning the limits

of the school space-time continuum and the rules of

governance and communication. Such resolutions

are relevant in a context in which very young

children are concerned, since they are to use these

platforms without having prior social digital skills.

REFERENCES

Bardin, L, 1996. L’analyse de contenu. Paris, PUF.

Babic, S., 2012. Factors that influence academic teacher’s

acceptance of e-learning technology in blended

learning environment. E-Learning-Organizational

Infrastructure and Tools for Specific Areas, p.3–18.

Berry, M, 2005. An investigation of the effectiveness of

virtual learning environment implementation in

primary school. Thesis University of Leicester.

Blin, F. & Munro, M., 2008. Why hasn’t technology

disrupted academics’ teaching practices?

Understanding resistance to change through the lens of

activity theory. Computers & Education, 50(2), p.

475-490.

Bobillier-Chaumon, M.E., 2013. Conditions d’usage et

facteurs d’acceptation des technologies dans l’activité

: questions et perspectives pour la psychologie du

travail. HDR Thesis. 205 p.

Bruillard, E., 2011. Le déploiement des ENT dans

l’enseignement secondaire : entre acteurs multiples,

dénis et illusions. Revue française de pédagogie, 177,

p.101-130.

Bruillard, E., & Hourbette, D., 2008. Environnements

Numériques de Travail, un modèle bureaucratique à

modifier. ARGOs, 44, p.29-34.

Budiu, R. & Nielsen, J., 2010. Children (Ages 3-12) on the

Web (2nd edition). NN Group.

Davis, F.D., 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS Quarterly, 13, p.319-340.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamaki, R.L., 1999.

Perspectives on Activity Theory, Cambridge

University Press.

Flanagan, J. C., 1954. The Critical Incident Technique.

Psychological Bulletin, 51, p.327-358.

Firmin, M. & Genesi, D., 2013. History and

implementation of classroom technology. Procedia-

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, p.1603-1617.

Karasavvidis, I., 2009. Activity Theory as a conceptual

framework for understanding teacher approaches to

Information and Communication Technologies.

Computers & Education, 53(2), p.436-444.

Keller, C., 2006. Technology acceptance in Academic

Organisations: Implementation of Virtual Learning

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

306

Environments. Proceeding of the 14th European

Conference on Information Systems, Gothenburg.

Keller, C., 2009. User Acceptance of Virtual Learning

Environments: A case Study from Three Northern

European Universities. Communications of the

Association for Information Systems, 25(1), Available

at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol25/iss1/38 25(38).

Kolias, V., Mamalougos, N., vamvakoussi, X., Lakkala,

M., & Vosniadou, S., 2005. Teachers’ attitudes to and

beliefs about web-based Collaborative Learning

Environments in the context of an international

implementation. Computers & Education, 45(3),

p.295-315.

Kuutti, K., 1996. Activity theory as a potential framework

for human-computer interaction research. Nardi B.

(ed.), Context and consciousness. Activity theory and

human computer interaction, Cambridge, MA: The

MIT Press.

Lueder, R., & Rice, V. J., 2007. Ergonomics for Children:

Designing Products and Places for Toddlers to Teens,

Taylor & Francis.

Missonier, S., 2008. Analyse réticulaire de projets de mise

en œuvre d’une technologie de l’information : le cas

des espaces numériques de travail. PhD Thesis.

OECD. 2015. Student, Computers and Learning. Making

the Connection. PISA. OECD Publishing, Available

at: http://www.oecd.org/edu/students-computers-and-

learning-9789264239555-en.htm.

Osika, E., Johnson, R. & Buteau, R., 2009. Factors

influencing faculty use of technology in online

instruction: A case study. Online Journal of Distance

Learning Administration, 12(1).

Pacurar, E., & Abbas, N., 2014. Analyse des intentions

d’usage d’un ENT chez les enseignants de lycées

professionnels, In STICEF, 21, Available at:

http://sticef.org.

Poyet, F. & Genevois, S., 2010. Intégration des ENT dans

les pratiques enseignantes : entre ruptures et

continuités. Rinaudo J.-L. and Poyet F. (ed.)

Environnements numériques en milieu scolaire. Quels

usages et quelles pratiques ?, Lyon, INRP, p.23-46.

Prieur, M & Steck, P., 2011. L’ENT : un levier de

transformation des pratiques pédagogiques pour

accompagner les apprentissages du socle commun,

Colloque International INRP 2011.

Rabardel, P. & Bourmaud, G., 2003. From computer to

instrument system: a developmental perspective.

Interacting with Computers, 15(5), p.665-691.

Stiles, M.J., 2000. Effective Learning and the Virtual

Learning Environment. The Learning Development

Centre, Staffordshire University, UK.

Voulgre, E., 2011. Une approche systémique des TICE

dans le système scolaire français : entre finalités

prescrites, ressources et usages par les enseignants.

PhD Thesis.

The Acceptance of VLEs (Virtual Learning Environments) by Primary School Teachers

307