An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User

Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of

Information Systems Implementation

Antonio Ghezzi

Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di Milano,

Via Lambruschini 4B, 20156 Milan, Italy

Keywords: Information Systems, Alternative Genre, Enterprise Resource Systems, Allegory, User Engagement, Change

Management, Action Research.

Abstract: Genres of communications significantly influence the evolution of a field of research. In the Information

Systems (IS) domain, a debate has recently emerged on the chance to implement alternative genres to

generate unconventional ways of looking at IS-related issues. This study hence proposes to apply allegory

as an alternative genre to write publications accounting IS research. To exemplify the use of the allegory

genre, the study tackles the role of the action researcher to enable user engagement and change management

in the early phases of Information Systems implementation. The allegory is applied to the case of a Small-

Medium-Enterprise undergoing ERP implementation. Reflecting on the allegory and its interpretation, it is

argued that the action researcher can take a paramount role in IS change management as “user engagement

enabler”; from a writing genre perspective, it is claimed that allegory is particularly suitable for writing

action research accounts.

1 INTRODUCTION

The evolution of a field of research like that on

Information Systems (IS) inherently relates not only

to the content of investigation – in either its

theoretical or empirical forms – and to the

methodologies applied to conduct the research

endeavor; it is also significantly shaped by the

writing genre traditionally applied as a vehicle to

report its content and findings.

In the last years, an intriguing debate has

emerged with regards to the genres to be applied

when writing academic publications (Rowe,2012).

IS scholars and practitioners are currently discussing

the opportunity to apply alternative genres in IS

research representation. According to Mathiassen et

al (2012), the term “alternative genres” refers to

unconventional forms of thinking, doing, and

communicating scholarship and practice. In

particular, it is related to innovation with respect to

epistemological perspectives, research methods,

semantic framing, literary styles, and media of

expression.

Provided that alternative genres are not valuable

per se, but they become significant once they are

fruitfully applied to writing studies on relevant IS

issues, propose the adoption of alternative genres to

tackle a significant problem in IS research: user

engagement and change management in the early

phases of Information Systems implementation –

with specific reference to Enterprise Resource

Planning (ERP) systems. To address this problem, I

take the methodological perspective of an action

researcher directly involved in the problem’s

observation and solution, and propose to employ the

alternative genre of “allegory” to allegorically

describe the role action researchers can play in

enabling user engagement and change management

in the early phases of ERP implementation.

Reflecting on the allegory and its interpretation,

this study argues that the action researcher can take a

paramount role in the IS change management

process as “user engagement enabler”; from a

writing genre perspective, the study also proposes

that allegory can be beneficially applied as a genre

to write action research accounts, due to the genre’s

peculiar characteristics.

Ghezzi, A.

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information Systems Implementation.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 1, pages 29-39

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

29

2 THEORY: CHANGE

MANAGEMENT AND USER

ENGAGEMENT IN IS

IMPLEMENTATION

Change is an ever-present feature of organizational

life both at an operational and strategic level

(Burnes, 2004), and since information technology

and organizational change show an inherent strong

relationship (Markus and Robey, 1988), the issue of

managing change determined by the introduction of

new IS within an organizational setting has been a

core theme in Information Systems (IS) research and

practice (e.g. Aladwani, 2001; Lim et al., 2005)

In general terms, change management could be

defined as “the process of continually renewing an

organization’s direction, structure, and capabilities

to serve the ever-changing needs of external and

internal customers” (Moran and Brightman, 2001).

Both Organizational and IS theories widely

recognize how Information Technology (IT)

influences the nature of work, thus catalysing

innovation while forcing incremental or radical

organizational redesign (Thach and Woodman,

1994).

Through implementing IT, organizations aim at

increasing process efficiency and effectiveness (with

a possible beneficial impact on outward

performance), although they also trigger inward

organizational effects that mostly reflect on

employees’ routines, practices, habits and

perceptions (Thach and Woodman, 1994): these

non-trivial, subtle effects require dedicated effort to

be understood and handled.

Focusing on the IS field, change management

hence tackles the problem of how to govern the

organizational transition determined by the

introduction of new information technologies and

systems (Markus and Robey, 1988).

Several studies have tackled the issue of user

engagement in IS implementation, finding that such

engagement is influenced by different factors. In his

seminal work “Psychology of innovation

resistance”, Sheth (1981) argued that there are two

main sources of resistance to IS innovations:

perceived risk, which refers to one’s perception of

the risk associated with the decision to adopt the

innovation; and habit, which refers to current

practices that one is routinely doing. Joshi (1991)

applied equity theory to IS implementation and

found that individuals attempt to evaluate all

changes on three levels: (i) gain or loss in their

equity status; (ii) comparison between personal and

organizational relative outcomes; and (iii)

comparison between personal and other user’s

relative outcome in the reference group. They only

resist to changes they see unfavourable, while

changes that are favourable are sought after and

welcomed. Gefen (2002) identified users’ trust as a

key determinant for their engagement in the complex

process of ERP system customization: trust was

increased when the vendor behaved in accordance

with client expectations by being responsive, and

decreased when it behaved in a manner that

contradicted these expectations by not being

dependable. Lim et al. (2005) investigated user

adoption behavior and motivation dynamics of ERP

systems from an expectancy perspective, and

claimed that managerial actions shall target different

levels of motivational factors to avoid counter-

productive dissonances. Wang and Chen (2006)

found that assistance of outside experts in ERP

implementation is inevitable: competent consultants

can facilitate communication and conflict resolution

in the ERP consulting process and assist in

improving ERP system quality.

Beyond identifying the factors behind user

engagement, particularly relevant to this study are

also two process models designed to obtain and

enhance engagement.

According to organizational theory, change

management aimed at cognitive redefinition of

users’ attitude and behaviour should follow a

process model called the force field model, made of

three stages (Schein and Bennis, 1965; Schein,

1999): (i) unfreeze the existing condition and apply

a force to it in the attempt to motivate users to

change; (ii) change and movement to a new state, by

focusing on training and communication; and (iii)

re-freeze to make new behaviours become habitual

or institutionalized routines.

In assessing the complex social problem of

users’ resistance to ERP implementation, Aladwani

(2001), elaborates on Sheth’s (1981) model and

proposed a process-oriented conceptual framework

consisting of three phases: (i) knowledge

formulation (where insight is gathered on needs,

values, beliefs and interests of future IS users); (ii)

strategy implementation (where change management

leverages tools such as communication, endorsement

and training to create awareness, stimulate feelings

and drive adoption, by constantly confronting habits

with perceived risks; and (iii) status evaluation

(where the progress of ERP change management

effort is monitored).

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

30

3 RESEARCH SETTING

The company this study considers is a Small

Medium Enterprise (SME) operating as an artistic

exhibition designer and manufactured, run and

owned by a Chief Executive Officer who inherited it

from his father. The company began operations in

the early fifties and in 2012 it had gained worldwide

recognition, being involved in several projects with

renown institutions, such as the British Museum, the

Tower of London Museum, the Louvre in Paris, the

Museum of Modern Arts and the Metropolitan

Museum in New York.

As the company grew globally, however, it was

shaped by two diverging thrust: on the one hand, the

CEO aimed at maintaining the company’s

inheritance of a SME and its craftsman approach

towards each activity and work; on the other, a

compelling need for organic development and

structuration was perceived by the management. As

a result, the organizational evolution was to some

extent convoluted and not fully consistent: while

some functions (e.g. design and manufacturing)

operated with a high degree of structuration and

technology support, others (e.g. administration,

procurement, project management and marketing)

were almost completely unstructured. Furthermore,

Information Technology did not evolve alongside

the company’s manufacturing technologies. The

little IT function was largely focusing on

maintaining the computers used for running

Computer Aided Design and Computer Aided

Manufacturing software; data analysis and storing

was either based on mere spreadsheets, or more

frequently, on paperwork.

In late 2012, when the action research process

began, it was time to make a strategic decision about

IT. The management team had been consulting a

shortlist of IT vendors for three months, and the

most promising solution proposed was that of

implementing an Enterprise Resource Planning

(ERP) system to centralize and support information

management and workflow throughout the

functions. However, the CEO had profound doubts

about this change, and his worries were somewhat

justifiable. The CEO foresaw the introduction of

such a pervasive system would determine radical

modifications in several areas, with unpredictable

results; he also he expected some of his employees

to eventually resist to or impair the IT project. On

top of this, he held a Philosophy and Literature

background, which gave him an anti-conformist and

original perspective on many strategic or

organizational issues, including technology: he had

contrasting feelings concerning IT, which he liked to

philosophically define as “a robot with huge

potential to enhance human’s capabilities, but after

all, a robot with no will and no creative value in

itself other than that of the human utilizing it”.

The CEO’s and his top management’s primary

concern was hence to adequately set and manage

this IS transition.

4 ACTION RESEARCH

METHODOLOGY

Action Research (AR) was primarily developed

from the work of Kurt Lewin and his colleagues, and

is based on a collaborative problem-solving

relationship between the researcher and the client

system, aiming at both managing change and

generating new knowledge (Coghlan, 2000).

As a form of qualitative research (Myers, 1997),

AR is described as a setting in which a client is

involved in the process of data gathering, which is

prevailingly under the charge of a researcher.

Avison et al. (1999) define AR as an iterative

process involving researchers and practitioners

acting together on a particular cycle of activities,

including problem diagnosis, action intervention,

and reflective learning. According to Rapoport

(1970), “action research aims to contribute both to

the practical concerns of people in an immediate

problematic situation and to the goals of social

science by joint collaboration within a mutually

acceptable ethical framework”. Indeed, action

Research is perhaps the most widely discussed

collaborative research approach (see Baskerville and

Wood-Harper 1998, Davison et al. 2004).

The collaboration this study depicts by means of

the allegory alternative genre is set in an artistic

exhibition design Small Medium Enterprise (SME)

and began with the identification of a problem, i.e.

the need to support the SME’s CEO and Project

Manager in enabling and managing change from a

basic and piecemeal approach towards technology to

the implementation of a broader ERP system. More

specifically, the CEO and the Project Manager were

concerned with user engagement, resistance to

change and communication issues that could burden

the early implementation phases.

This complex problem brought together multiple

participants, all of whom had an interest in solving

it. The set of participants included: Chief Executive

Officer; the management team; the internal Project

Manager; the SME’s employees (also referred to as

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information

Systems Implementation

31

users); the IT Vendor’s Marketing Manager; and the

team of three Action Researchers.

The problem that needed a solution was not

easily solvable within the current community of

practice inside of the company, who lacked specific

IS and change management competencies, and

furthermore called for the combination of

knowledge from multiple perspectives, expertise,

and disciplines (Mohrman et al., 2008). Hence, a

problem-focused research approach like AR could

provide a natural home for and evoke a need for

collaboration that brought together multiple

perspectives, including those of theory and practice.

In part, this is because problems represent

anomalies, and present a need to step outside of the

daily reality that is driven by implicit theories, and

to try to achieve a detachment that enables the

search for new understandings that can guide action

(Coghlan, 2000).

In order to solve the previously identified

problem, from December 2011 to March 2012, the

researchers who are authoring this study where

directly involved in the early stages of the

implementation process of an Enterprise Resource

Planning system within the SME (thus following the

direct involvement principle of the action research

methodology), with the planned overarching

objective to apply change management and

organizational communication practices supporting

the early phases of ERP implementation – with a

focus on enhancing user engagement. Although the

whole implementation project lasted till April, 2013,

this study focuses on allegorically describing its first

four months, where change management practices

and user engagement dynamics where at the heart of

the discussion.

The AR process was organized through a series

of weekly meetings (for a total of 21 meetings, each

lasting 2 hours 40 minutes on average) that the

action researchers alternatively held with all the

actors involved (including users). The content of

such meetings was previously planned with and

agreed upon by the CEO and the Project Manager,

and these actors were open to the researchers’

proposed lines of intervention. In the meetings, the

action researcher set a flexible agenda, checked the

progress status of previously identified actions,

gathered insights from the participants, provided

new content for discussion, set and explained new

action points and assignments and instructed

participants on how to act upon them.

In parallel, action researchers were involved in

supporting the change management and

communications activities and observing the user

engagement process almost of a daily basis, in order

to gather further information relevant to the

research; they also operated “shoulder to shoulder”

with the CEO and the Project Manager, and the

result of this was that the researchers not only gained

a deeper understanding of the company, its culture

and its management’s approach, but also gradually

became accepted as a non-threatening and legitimate

presence (Coghlan, 2000).

5 ALLEGORY AS ALTERNATIVE

GENRE: DEFINITIONS,

STRUCTURE AND

PRINCIPLES

An allegory is “the representation of abstract ideas

or principles by characters, figures, or events in

narrative, dramatic, or pictorial form”, and “a story,

picture, or play employing such representation”

(American Heritage Dictionary, 2011), where “the

apparent meaning of the characters and events is

used to symbolize a deeper moral or spiritual

meaning” (Collins English Dictionary, 2003).

The term derives from the Greek allēgoría,

derivative of allēgoreîn, i.e. to speak so as to imply

something other. As a rhetorical device, an allegory

is a figure of speech that makes wide use of

metaphors (i.e. “a figure of speech in which a word

or phrase is applied to an object or action that it does

not literally denote in order to imply a resemblance”

– Collins English Dictionary, 2003) and symbols

(i.e. “something that represents or stands for

something else, usually by convention or

association, especially a material object used to

represent something abstract” – Collins English

Dictionary, 2003), though extending them to a

complete and sense-making piece where complex

ideas are illustrated by means of text or images that

can be understood by the reader or viewer.

The very definition of allegory as a genre may be

controversial. As the concept of genre represents a

meaningful pattern of communication which consists

of a sequence of speech acts (Yetim, 2006), and

provided that “a genre is a category of art

distinguished by a definite style, form or content”

(American Heritage Dictionary, 2011), allegory is

hard to fix since its convention are less formal or

external, they are rather informal, skeletal or

structural.

However, Quilligan (1979) in her book “The

language of allegory: Defining the genre” argued

that allegory is a genre, i.e. “a legitimate critical

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

32

category of a prescriptive status similar to that of the

generic term ‘epic’”. Quilligan identifies the four

main features that define the genre of allegory and

its structure:

i. Text – the textual nature of the allegorical

narrative, which unfolds as a series of punning

commentaries related to one another;

ii. Pretext – which addresses the question of

that source of which always stands outside any

allegorical narrative and becomes the key to its

interpretability (though not always to its

interpretation). The relation between the text and the

pretext is necessary slippery, yet by gauging its

dimensions, we can begin to articulate the affinity of

allegory as literary criticism to allegory as literary

composition;

iii. Context – which addresses the question of

formal evolution by tracking the cultural causes of

allegory (allegories from different period may differ,

since linguistic assumptions differed as well);

iv. Reader – which represents the final focus

of any allegory, and the real action of any allegory is

the reader’s learning to read the text properly.

“Other genres appeal to readers as human beings;

allegory appeals to readers as readers of a system of

signs, so it appeals to them in terms of their most

distinguishing characteristics: as readers of, and

therefore as creatures finally shaped by, their

language” (Quilligan, 1979: 21).

The text and pretext hence focus on what the

texts themselves say about the genre; the context

provides the historical milieu out of which the

author may write an allegory; and the reader is the

ultimate producer of meaning (Nelson, 1968).

Considering that the primary characteristic of

allegory as a genre is to separate the representation

meaning from the inner and implied meaning, a

mode of analysis for allegory can rely on

hermeneutics (Myers, 1997). Hermeneutics is a

classical discipline primarily concerned with the

meaning of a text, and provides approaches to

interpret it. The most common of such approaches is

known as the “hermeneutic circle”, which refers to

the dialectic between the understanding of the text as

a whole (a theory) and the interpretation of its details

(single words), where the two dimensions are

reciprocally validating and help deciphering the

hidden meaning from the apparent meaning of

narrative (Gadamer, 1976).

In the allegory this study presents, the whole

story should be hermeneutically interpreted from the

theoretical lenses of change management and user

engagement in ERP implementation, while the

details refer to specific aspects that influence and

make sense within such context.

6 ALTERNATIVE GENRE

APPLICATION: THE

ALLEGORY OF THE SMALL

VILLAGE

A small village was located in a wood and

surrounded by a barriers of trees. The barrier was

so thick nobody could actually see what was beyond

it, and although it could be trespassed, no one had

ever been bold enough to make the attempt. Rays of

light made it through the ceiling of trees’ branches,

but branches were so many and intricate that the

village was most of the time dark and surrounded by

shades.

In the village lived a small community, who

gathered to follow the lead of one whose visions

were so fascinating and original that their heart was

captured by them: he believed that human beings

were meant to create works of art, and

craftsmanship was mankind’s deepest and essential

virtue. The people from the village called him the

Father, and once they stopped wandering in the dark

of the wood to share his vision, the Father welcomed

them in his community and taught them his idea of

art as a form of beauty all men should pursue. From

that time on, the Villagers’ highest aspiration hence

became to put such beautiful vision into practice.

They began collecting or even manufacturing

tools they could use from what the wood offered

them, and gathered into smaller groups of people

whose abilities lied in one piece of art or another. As

time went by, the Father selected a few chosen to

help him lead his community that was growing, he

called them the Wise Men and placed them at the

lead of those smaller groups. The results of all their

efforts were extraordinary, and notwithstanding the

hardship they were confronted with, their masterful

hands created objects of rare beauty.

Passers-by who were wandering nearby the

village through the thick woods were fascinated by

their works of art, and started asking for them: in

return, they offered rewards coming from outside of

the village they had been collected, and the village

grew richer.

Word of the beauty of the crafts the community

created spread, and soon many passers-by reached

to the village to demand for the Villagers’ pieces of

art. At first, the Father and the Wise Men met these

requests with joy, but soon they all realized the

requests could not be met: the tools and instruments

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information

Systems Implementation

33

their Villagers assembled to craft their art were

incapable to perform the complex activities passers-

by started asking for; and the wood, with his almost

perennial darkness, was a difficult place to work in.

In the long nights in the wood, the Father tried to

find a solution: however, his wisdom and art lied

elsewhere, and the problem remained unanswered.

Then came the Wizard. He wore a cloak who

concealed his figure, and he spoke a language no

one in the village could understand. But he brought

light: a light he could control, he could lit and stop

at his will; a light Villagers could use to assemble

new tools, to perform new works of art, and to

illuminate the gloomy darkness of their village.

Still, the Wizard’s mysterious light was met with

doubt, or even fear: Villagers did not know where it

came from, how to use it, and they were frightened

by it. The Father perceived an inner power in that

light, but it was something he could not fully

comprehend himself: so he decided to host the

Wizard in the village until he could unveil his

mystery.

Some time passed, and a small group of

Travelers, packed with big rucksacks on their

shoulders, reached the village. These Travelers had

seen some of the outer world and visited other

villages before: but most shockingly, they seemed to

understand part of what the Wizard was saying.

While all other passers-by just came and went, the

Father asked the Travelers to stay and help him

disclosing the power of light.

The Travelers spent their days with the Father,

to learn about the Villagers’ habits; soon, they

sympathized with them, and began understanding

their fear for the new source of light, as well as their

frustrations for the way they had been performing

their activities till that day. The Travelers also

attempted to speak with the Wizard, to understand

his light’s potential.

Villagers were afraid of relating with the Wizard,

and were ashamed to talk to their Father about their

dissatisfaction, but they felt they could confide in the

Travelers and be open with them: after all, the

Father introduced them, and it seemed a

comfortable aura surrounded them.

Since the Father had many duties to perform as a

leader of his community, he entitled a Wise Man to

accompany the Travelers for all the time of their

stay. The chosen Wise Man made sure all Villagers

paid attention to the Travelers’ questions and

requests, and eventually learnt to understand some

of the things the Wizard said or did.

It took many days to the Travelers to see,

understand, reflect and learn; often, they were also

seen walking around the village with awkward

objects they pulled out of their rucksacks; but

eventually they told the Father and his Wise Men

that there was nothing to be feared about the light,

although they needed them and all the Villagers to

see this with their own eyes. And the Father agreed.

First, the Travelers convinced the Wizard to

remove his cloak, to show everyone in the village he

was a man like all the others; then, they helped him

showing how the light could be used in the village to

help or change what Villagers currently did. A big

brazier was placed in the center of the village, and

the light coming from it was strong and warm; the

brazier could be a main source of light, but many

other lights could be lit from it, and they could be

used by the smaller groups of Villagers to perform

their specific activities, shining from darkness; also,

that light could alter forever the way the Villagers

crafted their beautiful objects.

The Villagers were indeed impressed, but many

of them were still frightened. The light could burn,

they were used to darkness, and they had been using

their skills in a certain fashion since they first joined

the community. The Travelers hence knew that

demonstrating the light’s power was not enough:

they needed to stay longer.

Almost each day since the brazier of light was

brought in the village, the Travelers met with each

Villagers, and then with the smaller groups of

Villagers, reminding them of how dark their days

were before the light came; they once again pulled

some of their awkward objects out of their rucksacks

and explained they came from their previous travels

– many of them they even inherited form Travelers

who lived in the past – and used them to show how

the light helped others before the Villagers, and, by

applying small changes to the objects, they could

also show how the light could possibly help their

own village. Then they asked the Villagers to tell

stories on how the light could change their activities,

the art they craft, and their lives, exposing their

fears but also their hopes, and although several

Villagers and even a few Wise Men were reluctant

or shy to make up their own story, eventually the

Father and the Travelers could convince them; and

all these stories were reported to the Father and the

Wizard, to make sure no voice would be left

unheard. The Wizard was himself reluctant, as he

could not see the reason why he should listen to the

Villagers stories told in a different language than his

own, but once again the Travelers were able to

persuade him to change his perspective of reality

and see it with the Villagers’ eyes.

When a Villager complained or seemed to be left

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

34

apart, the Travelers spent time with her or him to

understand the reasons, and all were treated the

same way. The Travelers also got the Wizard to

share his knowledge, and they translated while he

taught the Villagers how to employ the light in many

different ways. Those who proved remarkable skills

at the new activities were also rewarded and

indicated as examples to follow; some Villagers even

passed from one smaller group to another. The

Father and the Wise Men themselves showed

passion and interest in these new activities, and took

part to many of these gatherings.

Although the Villagers were still afraid of talking

to the Wizard alone, they trusted the Travelers, since

they never disguised themselves, they spoke a

language similar to theirs, they listened to everyone

and they had always treated everyone equally and

fairly.

Once the lights were used everywhere in the

village, the Father gathered all his community and

said the dark age was over and would never return.

A new era had started for those who lived in the

village: craftsmanship had eventually found a new

and more sophisticated instrument to be pursued.

The Travelers could hence leave the village,

towards another endeavor.

7 DISCUSSION

7.1 Contribution to IS Practice

Applying the hermeneutical mode of text analysis

(Gadamer, 1967) to the allegorical representation of

ERP implementation allows to individuate two

layers of meaning: (i) the apparent meaning, i.e., the

way the narration is presented and appears as such;

and (ii) the hidden meaning, i.e., the implied sense

of the narration in the light of the IS issue tackled.

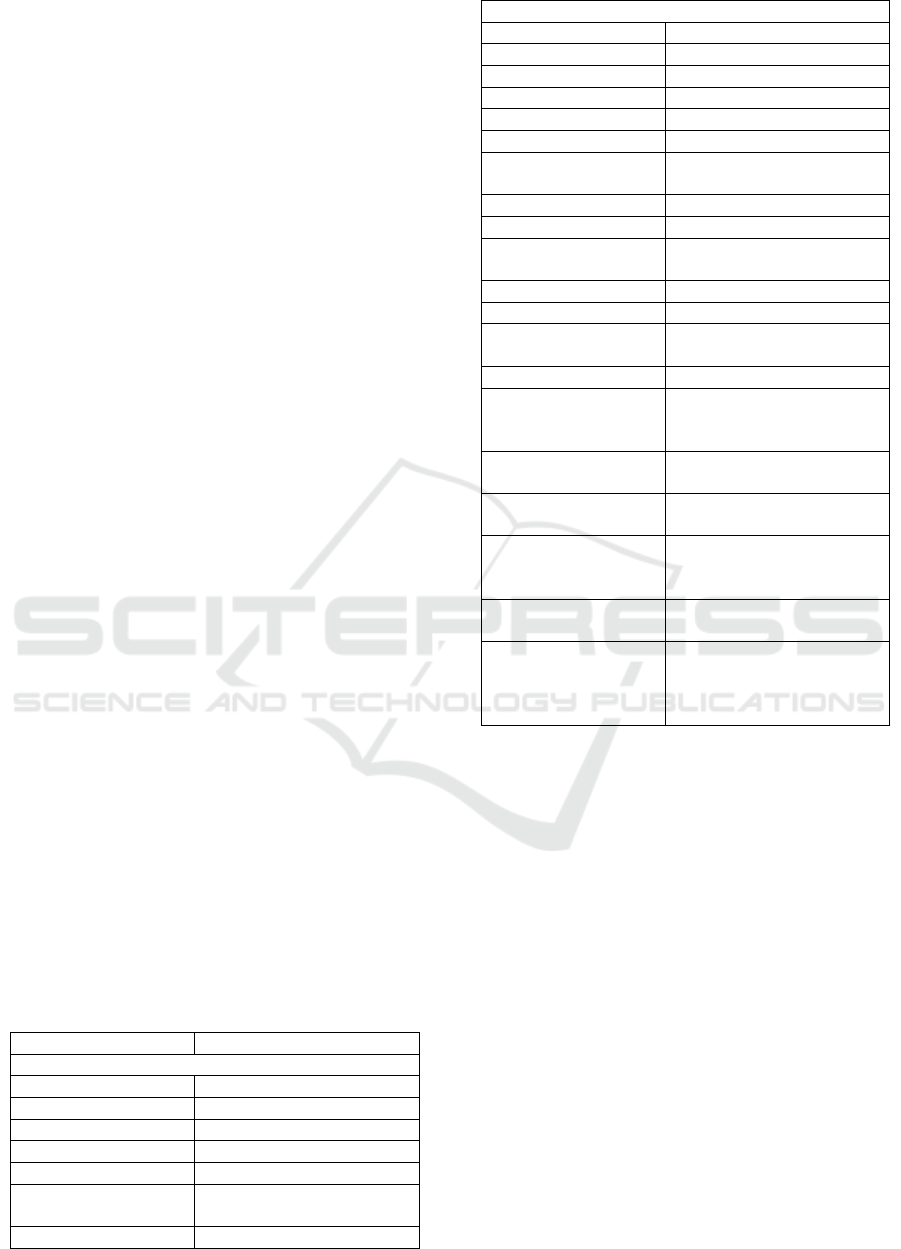

Table 1 shows the apparent and hidden meaning

for each of the allegory’s characters and elements.

Table 1: Apparent and hidden meanings in the small

village allegory.

Apparent meaning Hidden meaning

Allegory characters

The Father The CEO

The Wise Men The Top Management

The chosen Wise Man The Project Manager

The Villagers The Employees

The Passers-by The Customers

The Wizard The ERP Vendor’s

Marketing Manager

The Travelers The Action Researchers

Allegory elements

Small village SME

Wood Environmental complexity

Barrier of trees Closed approach

Darkness Lack of technology

Works of art SMEs products

Craftsmanship Working skills

Smaller groups of

villagers

SME’s division of

labor/functions

Rewards Revenue streams

Wizard’s language IT language

Wizard’s cloak IT Professionals’ different

background

Villagers’ language Natural language

Light Technology

Travelers’ rucksacks Action Researchers’

theoretical background

Travelers’ aura Academic credibility

Travelers’ objects

pulled out of the

rucksack

Action Researchers’

theoretical models

Father’s community

duties

CEO’s managerial tasks

Big brazier at the

center of the village

ERP system

Smaller sources of

light springing from

the brazier

ERP modules supporting

SME’s functions

New instruments New technological

applications

Villagers’, Wise

Men’s and Wizard’s

reluctance and

shyness

Communication resistance

to storytelling

The action research methodology and the change

management theory provide the theoretical framing

to decipher the hidden meaning of the allegory,

whose implications for IS practice are various.

The allegory shows how action researchers acted

in the empirical setting of a SME where the

introduction of an ERP system was determining

significant changes in the way users organized and

performed their work and interpreted their

organizational self.

The company was held together by the CEO’s

passion and eclectic leadership, although it started

encountering significant issues as demand increased

and became varied; moreover, the technological

skills at hand were insufficient to govern a

growingly complex company, but the CEO and his

Top Management had little or no knowledge of IT.

They perceived the opportunity represented by the

ERP system, but were not capable of grasping it and

a management-vendor leap appeared: this situation

was similar to what Wang and Chen (2006) reported,

where the lack of internal IT skills makes way for

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information

Systems Implementation

35

external support. However, instead of looking for

external consultancy firms or vendors to obtain such

support, the company’s CEO turned to action

researchers. The involvement of action researchers

in the project hence came with several advantages,

and their role was crucial in key stages of the change

management and user engagement process.

Action researchers first acted to demystify the

new IS, by supporting the IT vendor in translating

the IT language into natural language users could

understand; by being almost ever-present they were

responsive, and made sure the IT vendor removed

his cultural “cloak” to become dependable and

trustworthy (Gefen, 2002). Because of their

academic status, an “aura” of credibility surrounded

them from the management’s and the users’

standpoint, so they were seen as a much more

reliable listeners than the IT vendor himself or any

external consultancy firm could ever be: this aspect

paved the way for open discussion, communication

and sharing, all key elements in change management

(Schein and Bennis, 1965; Gallivan and Keil, 2003).

Action researchers also played an intermediate

role between the CEO, the Project Manager and

users. They received endorsement from the CEO and

worked shoulder to shoulder with him and the

Project Manager to govern the change, so that the

management could keep indirect control over the IS

implementation’s early stages without the risk to

either abandon other managerial tasks supporting the

business as usual (the “community duties”) or be

perceived as poorly committed to the innovation

taking place; the researchers also had the CEO and

the Top Management be involved in milestone steps

of the project (e.g. kick-off meeting and regular

meeting) and play as committed “ERP champions”

to boost motivation for user adoption (Lim et al.,

2005; Brown and Jones, 1998). Users did not enjoy

complaining with their managers, and appreciated

the role of the action researchers as trusted third

parties they could rely on, as they perceived the

researchers could collect their thoughts and feelings,

relate them, add their own expertise and present

them to the CEO and Project Manager in an

organized, sound and apparently impartial mode.

Action researchers performed in a way that

aimed at closing all the communication leaps and

lapses (Gallivan and Keil, 2003) at three levels: (i)

users-management; (ii) users-IT vendor; and (ii) user

group-user group. In this process, action researchers

became a sort of central buffer between the “Father”

and the “Wise Men”, the “Villagers” and the

“Wizard”, to solve all possible controversies arising.

Consistently with the tenets of the equity-

implementation model (Joshi, 1991), action

researchers took the role of “organizational

equalizers” and used communication devices to

support the idea that no inequalities or loss of

equities were perpetrated, so that the transition could

be accepted and welcomed, rather than resisted.

User engagement was a priority in the change

management process, and action researchers acted

following a contingent approach that mixed

rationalism (e.g. IS and change management theories

and models) and experiments (e.g. hands-on

training, exemplification, learning by doing and

trial-and error approach) on the basis of their

acquired knowledge of the specific research setting

(Saarinen and Vepsäläinen, 1993) to enable it. They

based their actions on the constant confrontation of

users’ habits and perceived risks (Sheth, 1981) to

drive ERP adoption.

They were eventually the main actors to trigger

and govern the unfreezing, change, re-freezing

stages of the force field process model (Schein and

Bennis, 1965; Schein, 1999), by: (i) sympathetically

and empathically gathering knowledge on the needs,

values, beliefs and interests of future IS users

(Aladwani, 2001), feeding dissatisfaction over the

“dark days” when IT was not available while clearly

illustrating the benefits of the new solution; (ii)

providing constant communication support to the IT

Vendor as he tangibly started introducing the ERP

system in the company, while listening to the voices

of the internal customers and taking an active role on

training; and (iii) setting the basis for a re-freezing

of the newly acquired routines into institutionalized

practices that the top management agreed upon.

Most originally, this study illustrates how the

CEO and action researchers made use of

“storytelling” as a communication device to create

shared consensus on the IS transition:

employees/users were requested to express their

working expectations and feelings related to the new

IS, and this made for better interiorizing of change

and reduced long-term resistance. By doing so, the

CEO and the action researchers performed an

interesting paradigm shift in the classical approach

to change management (Kettinger and Grover,

1995): they created and inflated an initial

“communication resistance” aimed to lessen the

impact of any future “user resistance”. As the

allegory discloses, the process of approaching ERP

implementation through personal stories created

early inter and intra-organizational tensions, which,

however, in the short term eased participation,

involvement and commitment to use the newly

introduced system. Storytelling could hence become

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

36

part of IS change management practice, as a

valuable communication device to support the early

unfreezing and knowledge formulation phases where

information on the users’ habits and perceived risks

should be gathered.

7.2 Contribution to IS Publication

This study also suggests to employ allegory as an

alternative writing genres in IS publication.

An allegory can contain several layers of

meanings, thus making the narration

multidimensional and flexible and allowing to hide a

deeper moral behind a literal interpretation of the

text. The work of the IS action researcher/writer to

add these layers to the traditional representation of

her or his studies (as commonly reported in IS case

studies) certainly requires and additional narrative

effort: however, such work also forces the writer to

dialectically move from the meaning to its symbol,

from the symbol to a whole metaphor and then to the

extended metaphor represented by the allegory itself.

In this dialectic and iterative process, the

researcher/writer has the chance to: deeply elaborate

and reflect on the field data he collected; resort to a

combination of expertise, intuition and creativity to

develop an enlightening sensitivity towards the IS

problem investigated (e.g. IS change management);

describe such problem in a lively way where the

explicit and the implicit perspectives coexist and

both add to the account; and encourage the reader to

empathically embark in the same interpretation

process.

Thus, the allegory genre stimulates the

construction of many apparently different though

integrative narrations that can help the reader in the

gradual activity of disentangling multifaceted and

multidimensional IS problems and discover the

action researcher’s findings. A sense of empathic

“discovery” will then permeate the allegory and

accompany the reader during the interpretation

process, and this will make for better interiorizing of

the inner meanings – that is, the study’s findings.

Paradoxically, an allegory could hence tell more

of a writer’s insight, understanding and perspective

on a given IS phenomenon than a plain case

description would: the allegory has the power to

manage and convey the action researcher’s intended

meaning and personal insights which would have

largely been “lost in translation” in traditional

scientific writings. By properly framing the allegory

in a methodological and contextual background (like

this study attempts to do, by presenting the IS

change management and user engagement theory

and the action research methodology), the

researcher/writer could offer an hermeneutical tool,

a key to help the reader to translate metaphorical

concept into real-world IS phenomena and elements.

The theoretical and methodological frame would

hence serve as the allegory’s pre-text and con-text to

stimulate a profound understanding of the literal text

(Quilligan, 1979).

Due to its peculiarity, the alternative genre of

allegory could show further characteristics. It could

provide a narrative language that is appealing for a

wider range of readers (other than researchers or IS

specialists), possibly enlarging the target audience of

IS studies towards different disciplines like

Management; it could leverage symbolism and

metaphors to nuance critical messages (e.g. IT

vendor’s scarce dependability) and convey positive

or negative messages (e.g. “light” and “darkness”

equated to the presence or absence of technology)

that stay with the reader; and it could eventually

place the reader into a position of self-denying self-

consciousness (Quilligan, 1979), where he is more

open to discovery and learning of the allegory’s

moral.

This study contends that allegory as an

alternative genre could be most indicated to report

action research endeavors, considering this research

methodology’s inner characteristics. Action

researchers’ activity is inherently multi-layered (as

the allegory is): action researchers mix observation

and action, detachment and involvement, description

and normativity; they need to craft a narrative that

draws from multiple perspectives and possibly

unifies them into a single narrative; and their role is

intimately hermeneutical, as they strive to help

interpreting details in the light of the whole and

validate the whole by means of details. The

“Travelers” undertake journeys not only from

company to company, but also cross-domain travels

from theory to practice (and back to theory), from

literal meaning (i.e. empirical events) to hidden

revelations (theoretical and practical implications).

Eventually, they can provide the sound theoretical

and pragmatic key to read the allegory, always

keeping in mind that an invisible thread shall relate

the metaphor and the case they experienced (see

Table 1).

Exploiting allegory as an alternative genre would

constitute a normative breach that enables IS

publications based on action research cases to

overcome the limitations of canonical scientific

writing (i.e. constraints on figures of speech,

rhetorical devices and styles available; structural

rigidity; limited accountability of internal responses

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information

Systems Implementation

37

and motives, and limited perception of the

intentional state vs. external response dualism;

limited empathy and involvement evoked in the

reader), thus providing a truly multifaceted account

of the “organizational drama” (Avital and

Vandenbosch, 2000) behind IS adoption.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This study’s possible contribution is twofold.

Concerning IS practice, the allegory shows that a

contingent approach that combines communication,

endorsement, cognitive understanding and training

can enable change management where change is

caused by IS implementation. The study also

proposes to include “user storytelling” as a valuable

communication device to help the management and

the researchers reveal employees’ habits and

perceived risks related to technological change,

while buying them in in an emotional and empathic

way that helps leapfrogging traditional resistance to

change.

The first core claim from this study is that Action

Researchers can play a paramount role in enabling

and governing IS change management and users

engagement. The mediation between theoretical

detachment and professional involvement that

characterizes action researchers, together with the

“aura” springing from their academic background,

make them a trusted and dependable party users can

refer to in the often painful change process. Action

researchers can support the key stages of the change

management cycle by means of proper instruments

like communication, managerial endorsement and

training supervision, combined with their theoretical

and practical IS endowment, to create a comfort

zone for users where awareness is increased,

empathy is stimulated, conflicts are resolved and

adoption is driven.

The second core claim this study presents is that

allegory is an alternative genre that could be

beneficially employed to account for action research

endeavors. Allegory as a genre shows similarities

with the action researcher’s multi-layered and

multidimensional activity, and could force the

researcher/writer into a reflection, abstraction and

transposition cycle that could support his elaboration

of his study’s findings. The risk action researchers

run is to be so involved in the project they observe

and operate in that they eventually become incapable

to get detached from it and grasp its deeper findings

(that may be hiding below the surface of the

operational activities performed). Writing the action

research account in the form of an allegory demands

to reinterpret a factual case in the light of symbols

and metaphors that should connect to reality, while

offering the reader a set of interpretation lenses

borrowed from IS theory and practice. The positive

result of this process is an enhanced ability to

highlight the story’s findings. And the hidden

meaning of the allegory, once revealed and made

apparent to the reader through an hermeneutical text

analysis, could also allow deeper interiorizing of

such findings and meanings.

REFERENCES

Aladwani, A. M. (2001). Change management strategies

for successful ERP implementation. Business Process

management journal, 7(3), 266-275.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language,

Fifth Edition (2011). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Publishing Company.

Avison, D. E., Lau, F., Myers, M. D., and Nielsen, P. A.

(1999). Action research.Communications of the

ACM, 42(1), 94-97.

Baskerville, R., and Wood-Harper, A. T. (1998). Diversity

in information systems action research

methods. European Journal of Information

Systems, 7(2), 90-107.

Boje, D. M. (2001). Narrative methods for organizational

& communication research. Sage.

Boland, R., and Schultze, U. (1996). Narrating

Accountability: Cognition and the Production of the

Accountable Self", in R. Munro and R. Mouritsen

(eds), Accountability: Power, Ethos and the

Technologies of Managing. London: International

Thomson Business Press, 1996.

Brown, A., and Jones, M. (1998). Doomed to Failure:

Narratives of Inevitability and Conspiracy in a Failed

IS Project. Organization Science (19:1), pp. 73-88.

Burnes, B. (2004) Managing Change: A Strategic

Approach to Organisational Dynamics, 4th edn

(Harlow: Prentice Hall).

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, T. (2005) Doing Action

Research in Your Own Organization, SAGE

Publications, London.

Coghlan, D. (2000). Interlevel dynamics in clinical

inquiry. Journal of Organizational Change

Management, 13(2), 190-200.

Coghlan, D. (2011) Action Research: Exploring

Perspectives on a Philosophy of Practical Knowing.

The Academy of Management Annals 5(1), 53-87.

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged

(2003). HarperCollins Publishers, 2003.

Cortimiglia, M., Ghezzi, A. and Frank, A. (2015) Business

Model Innovation and strategy making nexus:

evidences from a cross-industry mixed methods study.

R&D Management, DOI: 10.1111/radm.12113.

Czarniawska, B. (2004). Narratives in social science

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

38

research. Sage.

Davison R., Martinsons, M. and Kock, N. (2004)

Principles of Canonical Action Research. Information

Systems Journal 14(1), 65-86.

Gadamer, H.G. (1976). Philosophical Hermeneutics.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gallivan, M., and Keil, M. (2003), The user-developer

communication process: a critical case study.

Information Systems Journal 13 (1), 37–68.

Gefen, D. (2002). Nurturing clients’ trust to encourage

engagement success during the customization of ERP

systems. Omega, 30(4), 287-299.

Ghezzi, A., Cortimiglia, M. and Frank, A. (2015) Strategy

and business model design in dynamic

Telecommunications industries: a study on Italian

Mobile Network Operators. Technological Forecasting

and Social Change Vol. 90, Part A, 346-354.

Ghezzi A., Georgadis M., Reichl P., Di-Cairano Gilfedder

C., Mangiaracina R. and Le-Sauze N. (2013)

Generating Innovative Business Models for the Future

Internet. Info 15(4), 43-68.

Ghezzi, A., Mangiaracina R. and Perego, A. (2012)

Shaping the E-Commerce Logistics Strategy: a

Decision Framework, International Journal of

Engineering Business Management, Wai Hung Ip

(Ed.), ISBN: 1847-9790, InTech.

Ghezzi, A., Renga, F., and Balocco, R. (2009) A

technology classification model for Mobile Content

and Service Delivery Platforms. In Enterprise

Information Systems (pp. 600-614). Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Joshi, K. (1991). A model of users' perspective on change:

the case of information systems technology

implementation. Mis Quarterly, 229-242.

Kettinger, W. and Grover, V. (1995) Toward a Theory of

Business Process Change Management. Journal of

Management Information Systems 12(1), 9-30.

Lanzara, G. F. (1991). Shifting stories. Learning from a

reflective experiment in a design process. In The

reflective turn: Case studies in and on educational

practice (pp. 285-320). Teachers College Press New

York.

Lim, E. T., Pan, S. L., and Tan, C. W. (2005). Managing

user acceptance towards enterprise resource planning

(ERP) systems–understanding the dissonance between

user expectations and managerial policies. European

Journal of Information Systems, 14(2), 135-149.

Markus, M. L., and Robey, D. (1988). Information

technology and organizational change: causal structure

in theory and research. Management science, 34(5),

583-598.

Mathiassen, L., Chiasson, M. and Germonprez, M. (2012)

Style Composition in Action Research Publication.

MIS Quarterly 36(2), 347-363.

Mohrman S.A, Pasmore W.A., Shani A.B. (Rami),

Stymne B., Adler N. (2008) Toward Building a

Collaborative Research Community, in: Shani A.B.

(Rami), Mohrman S.A., Pasmore W.A., Stymne B.,

Adler N. (Eds.) Handbook of Collaborative Ma-

nagement Research, Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

Moran, J. W. and Brightman, B. K. (2001) ‘Leading

organizational change’, Career Development

International, 6(2), pp. 111–118.

Myers, M. D. (1997). Qualitative Research in Information

Systems. MIS Quarterly (21:2), June 1997, pp. 241-

242.

Quilligan, M. (1979). The language of allegory: Defining

the genre. Cornell University Press.

Rapoport, R. (1970) Three Dilemmas of Action Research.

Human Relations 23(6), 499-513.

Rowe, F. (2012) Toward a richer diversity of genres in

information systems research: new categorization and

guidelines. European Journal of Information Systems

21, 469-478.

Saarinen, T., and Vepsäläinen, A. (1993). Managing the

risks of information systems implementation.

European Journal of Information Systems, 2(4), 283-

295.

Schein, E. and Bennis, W, (1965), Personal and

Organizational Change Through Group Methods: The

Laboratory Approach, New York: Wiley.

Schein, E. H. (1999). The corporate culture survival guide:

Sense and nonsense about culture change. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Sheth, J. (1981), “Psychology of innovation resistance”,

Research inMarketing, Vol. 4, pp. 273-82.

Thach, L., and Woodman, R. W. (1994). Organizational

change and information technology: Managing on the

edge of cyberspace. Organizational Dynamics, 23(1),

30-46.

Wang, E. T., and Chen, J. H. (2006). Effects of internal

support and consultant quality on the consulting

process and ERP system quality. Decision Support

Systems, 42(2), 1029-1041.

Yetim, F. (2006) Acting with genres: discursive-ethical

concepts for reflecting on and legitimating genres.

European Journal of Information Systems, 15(1), 54–

69.

Zwickl, P., Reichl, P. and Ghezzi, A. (2011) On the

quantification of value networks: a dependency model

for interconnection scenarios. In Economics of

Converged, Internet-Based Networks (pp. 63-74).

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

An Allegory on the Role of the Action Researcher to Enable User Engagement and Change Management in the Early Phases of Information

Systems Implementation

39