Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation

and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

Tamara Babaian, Wendy Lucas, Alina Chircu and Noreen Power

Bentley University, 175 Forest Street, Waltham, MA 02452, U.S.A.

Keywords: Dynamic Visualizations, Interactive Visualizations, Enterprise Systems, ERP.

Abstract: Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems pose usability challenges to all but the most sophisticated of

users. One such challenge arises from complex menu structures that hinder, rather than aid, system navigation.

Another issue is the lack of support for discovering and exploring relationships between the data elements

that underlie all transactions and processes performed with the system. Two dynamic, interactive

visualizations, the Dynamic Task Map and the Association Map, were designed to assist users in ERP system

navigation and data exploration activities. In this paper, we describe a laboratory study comparing the use of

these visual components to standard SAP interfaces. Results from an initial empirical evaluation revealed that

all users were able to complete tasks more quickly and with the same or a lower number of errors when using

the visual components than when using SAP. Answers to questions comparing the standard SAP interface

with visualizations also revealed an overall preference for the visual interfaces. Suggestions for improvements

to the visualizations from study participants provided valuable feedback for future development.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the first issue of Interactions, Myers (1994, p. 74)

wrote that “Time is valuable, people do not want to

read manuals, and they want to spend their time

accomplishing their goals, not learning how to

operate a computer-based system.” Over 20 years

later, many Enterprise Research Planning (ERP)

systems still stand between the users and their ability

to achieve their work-related goals. Companies have

learned the hard way that spending enormous

amounts of time and money on ERP system training

is a critical prerequisite for success. A case in point is

the well-known ERP failure at Lumber Liquidators,

which was blamed in large part on insufficient

attention to user training (Krigsman, 2010).

Even with considerable investments in training,

however, there are no guarantees that implementing

an ERP system will be successful and will lead to

increased productivity. Experience has shown that

poor usability characteristics are at least partly to

blame. Massive menu structures, inadequate

navigational guidance, limited task support, and

complex interfaces are just some of the obstacles

facing users of these systems (Topi, 2005; Rettig,

2007; Scholtz et al., 2010; Parks, 2012; Lambeck et

al., 2014a, 2014b).

The motivation for this research comes from the

belief that it shouldn’t require such vast resources on

the part of the company or herculean efforts on the

part of its employees for ERP usage to meet with

success. Today’s workers have become more

demanding of their office software after having

experienced user-friendly personal devices, and ERP

software providers are paying increased attention to

usability (King, 2012). A recent Gartner report

(Ganly and Montgomery, 2015) notes that ERP

vendors are looking to improve the user experience

by applying social software approaches to building

communication tools. This tactic, however, won’t

tackle the systemic causes of poor usability.

Interactive information visualizations, on the

other hand, can directly impact the user experience by

providing tools and techniques for, among other

things, selecting, filtering, exploring, and connecting

data items (Yi et al., 2007). While such techniques are

widely used by the visual analytics community (Pike

et al., 2009), interactive visualizations are not

prevalent in ERP systems.

In this paper, we present an empirical study of two

interactive visualizations designed to aid ERP system

users in navigation and data exploration tasks

(Babaian et al., 2015). The Dynamic Task Map

(DTM) helps users locate the desired functionality by

providing dynamic, interactive visualizations of

368

Babaian, T., Lucas, W., Chircu, A. and Power, N.

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 368-377

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

transactions performed with the system. It reveals

common usage patterns by visualizing measures that

reflect aggregate user activity, such as the frequency

with which a task has been performed. The

Association Map (AM) highlights associative

relationships between master data entities selected by

the user. It presents an easy to understand, aggregated

view of data relationships that would otherwise need

to be extracted from detailed reports.

Ten study participants, all of whom were novice

users of SAP, performed a set of tasks with each of

these components and answered questions related to

those tasks. They performed those same tasks and

answered the same questions using the corresponding

interfaces in SAP, a market leader in enterprise

application software (Drobik, 2015). The installation

used was SAP ECC 6.0 with SAPGUI 7.40 for

Windows. The participants also answered questions

comparing their experiences with each of the visual

interfaces to those with SAPGUI. All of the

participants took less time and answered at least as

many, and typically more, questions correctly with

the visual interfaces than with SAPGUI. The vast

majority also preferred the visual components.

In the next section of this paper, we review related

work. This is followed by a description of the

visualization components under investigation. The

user study setup is detailed and results from that study

are then presented and discussed. We conclude with

a summary of findings and directions for future work.

2 RELATED WORK

ERP usability issues have been documented in

industry reports and articles as well as research

studies (see, for example, Babaian et al., 2010;

Cooprider et al., 2010; Lucas and Babaian, 2012;

Scholtz et al., 2010). It has been readily

acknowledged that these systems are typically

difficult to use, particularly for novice users, and have

very long learning curves. A study by Topi et al.

(2005) defined six categories of usability problems,

including the identification of and access to the

correct functionality, system output limitations, and

overall system complexity. More recent studies

confirm that the issues identified in this work still

persist today (Parks, 2012; Lambeck et al, 2014a;

Lambeck et al., 2014b).

Rather than tackle ERP usability issues directly,

however, research has often focused on the “human

factor.” Hurtienne et al. (2009) describes three ways

for optimizing the fit between the user, the task, and the

software. The first is adapting the business processes to

the software (i.e., organizational change management).

The second is user training, and the third is changing

and adapting the software to the users and their tasks

via customization. They note that while the first two

approaches are critical for success, the third approach

of customization is usually discouraged. Given that

customization can be costly, time-intensive, and will

typically need to be re-implemented in new releases,

this is not surprising.

Having usability designed into the ERP system in

the first place would be a far more preferable option.

Integrating information visualizations into ERP

interfaces is one way to work toward achieving this

outcome. Parush et al. (2007) found that graphical

visualizations improved performance of ERP users on

tasks of varying complexity in two different task

domains: Purchasing and Production planning and

control. Visualizations can better represent

quantitative data, integrate data from multiple

sources, and aid decision-making. More advanced

visual-spatial displays can support multi-source

integration, which is essential for ERP performance,

and can improve user fit, which contributes to ERP

success (Hong and Kim, 2002).

A survey of 184 users of different experience

levels using a variety of ERP systems revealed that

being able to find the desired enterprise functionality

is still a problem across all user experience levels

(Lambeck et al., 2014a). They also found that the

availability of useful and numerous visualizations can

reduce user ratings of system complexity.

Supplementary systems were found to provide more

useful visualizations than ERP systems (Lambeck et

al., 2014b).

Hipp et al. (2012) point out that being able to

quickly and easily find process information during

process execution is critical, yet most business

processes are presented in a static way. Hipp et al.

(2014) present a navigation space for navigating over

large process model collections and related process

information. They have applied this approach to

complex, real-world automotive process models in an

application called Compass. A controlled user

experiment validated the usefulness of their three-

dimensional approach, which consists of semantic,

geographic, and view dimensions, for navigating

complex process model collections.

While visualizations are being applied to tools and

techniques for process navigation, discovery, and

mining (van der Aalst, 2011), they have yet to be

integrated in any significant way into ERP systems.

In the following pages, we present and evaluate visual

components that take us a step closer to the goal of

improving ERP usability via dynamic, interactive

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

369

visualizations.

3 ARTIFACTS

The two dynamic, interactive visualizations used in

the study described in this paper were the Dynamic

Task Map (DTM) and the Association Map (AM).

The DTM was developed to assist users in ERP

system navigation, while the AM supports data

exploration activities. Both were implemented in D3

(see http://d3js.org). Earlier versions of these

components were presented in Babaian et al., 2015.

3.1 Dynamic Task Map (DTM)

SAP, like other commercial ERP systems, includes a

central menu structure called the SAP Easy Access

Menu (see Figure 1), which is displayed on the

system’s front page. Despite its name, this menu is so

massive and unwieldy that most users tend to avoid

it, preferring to navigate the system by memorizing

transaction codes and entering them directly. The

only way to locate a transaction directly within the

SAP Easy Access Menu is by expanding the menu

branches and browsing the expanded view. SAP has

two separate search functions for finding a

transaction’s code and location within the SAP Easy

Access Menu. These functions, however, are not

integrated with the menu.

Within each transaction screen, there is a separate

menu with related tasks, located on top of the

transaction screen. All aforementioned menus are

fixed, in that they do not change with the use of the

system. SAP also provides a Favorites menu, which

can be configured by the users.

The Dynamic Task Map (DTM) provides an

alternative means for finding a transaction via a

dynamic, interactive visualization of transactions and

the links between them. These transactions and links,

along with their associated properties, are derived

from ERP systems logs.

Each task in the DTM is depicted by a circular,

blue node labelled with the task name, as shown in

Figure 2. The size of each node reflects the frequency

with which that transaction has been performed. In

the top left corner of DTM is a search interface, which

locates transactions by name or by code. The

visualization of all transactions does not display any

links, as the resulting view would be too cluttered to

be useful. Selecting a particular transaction, however,

will cause the display to zoom in and make visible the

links between that task and all transactions that

typically co-occur or follow it, as shown in Figure 3.

These connections are computed dynamically from

SAP’s internal usage logs, thus representing the

actual way people use the system.

Figure 1: SAP Easy Access Menu expanded to locate the

Change Material Type transaction.

Figure 2: DTM visualization of all transactions. No nodes

are selected. The search box appears in the top left corner.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

370

To select a transaction in DTM, the user can either

click on the node representing it or type its name

(partial or complete) or transaction code into a search

box. Figure 3 shows what is displayed after the user

has selected the “Change Material” transaction. As

can be seen, the selected node bears a larger label. The

name and transaction code for that node appear at the

top of the visualization.

Transaction codes can also be displayed by

hovering the mouse over a node. Connected

transactions are highlighted in red, with the intensity

of the color reflecting the likelihood of that

transaction following the selected one.

3.2 Association Map (AM)

Discovering relationships between master data

elements in ERP systems can be a challenging

process involving multiple steps. For novice users,

even knowing where to begin can be problematic.

Figure 3: Selected task (in yellow and with larger label) with connected tasks in varying shades of red to reflect frequency

with which they co-occur or follow the selected task. The top left corner contains the search interface, the title, and the code

of the selected transaction.

Figure 4: AM visualization of Vendor-Plant-Material relationships. Links to related entities appear in grey. The search

interface appears at the top of the visualization.

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

371

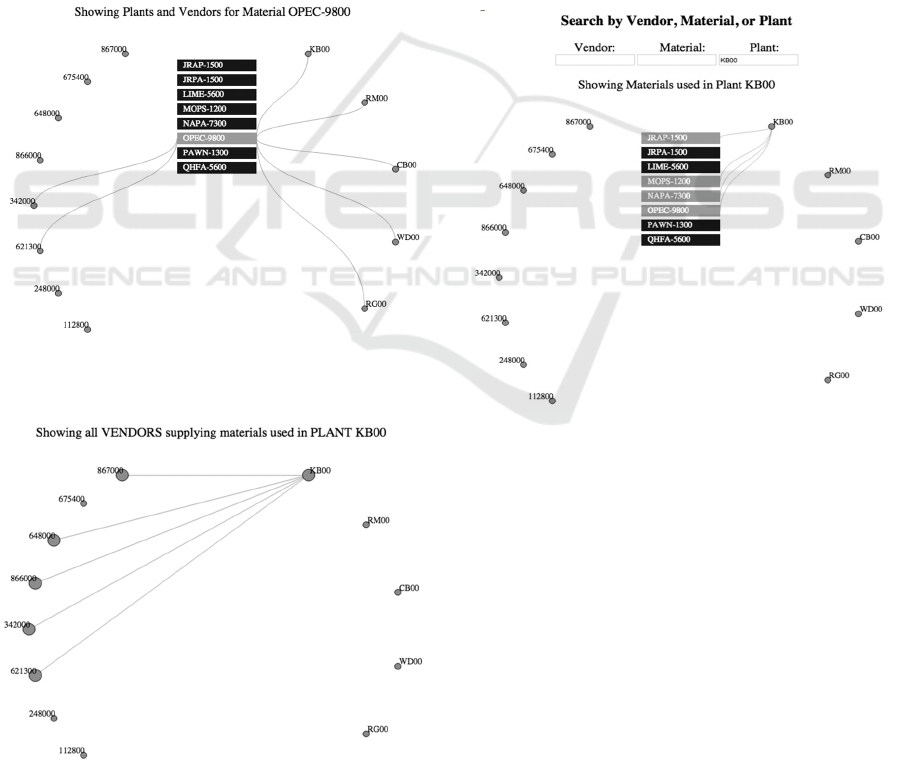

Figure 4 shows the visualization for exploring

relationships between vendors, materials, and plants.

Vendors are represented by blue circular nodes on the

left, plants by green circular nodes on the right, and

materials by brown rectangular nodes in the middle

Once the correct source document has been

identified, extracting and interpreting data from a

report designed to serve multiple purposes presents its

own challenges

The Association Map (AM) was designed to

provide users with an intuitive interface for exploring

many-to-many relationships. It extends the D3

concept map, (http://www.findtheconversation.com/

concept-map) by allowing the user to specify search

parameters of the page. Grey lines connect each

vendor to every material it supplies and each plant to

every material it stores. Each material can be supplied

by multiple vendors and stored in multiple plants.

Figure 5: Selection of Material OPEC-9800 from AM

search interface or AM visualization. The selected material

and links from it appear in pink.

Figure 6: Selection of Plant KB00 by pointing at its node in

the AM visualization shows links to vendors supplying

materials used by that plant.

To zoom in on a particular entity, the user can either

point the mouse at the node of interest or enter a

search term. For example, Figure 5 shows the

resulting visualization when the user either points at

the OPEC-9800 material or enters that name in the

Material field of the search interface.

Pointing a mouse at a vendor node will display all

plants using materials from that vendor, while

entering a vendor identifier to the search interface

will show all materials supplied by that vendor.

Similarly, pointing at a plant node will show all

materials stored by that plant, while entering a plant

identifier to the search interface will show all vendors

supplying materials to that plant. Figure 6 shows the

results of pointing at PLANT KB00. Note that the

nodes of vendors supplying materials used by that

plant are enlarged.

Figure 7 shows the display after the user has

specified a search on Plant KB00.

Figure 7: Selection of Plant KB00 from the search interface

shows all materials stored by that plant.

4 USER STUDY

In this section, we describe an experiment comparing

visual interfaces presented in this paper with the

navigation and association support interfaces in SAP.

Comparisons are in terms of user performance and

satisfaction.

4.1 Study Setup

We recruited thirteen study participants from

graduate students in a small business university. All

students were taking a course that involved the use of

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

372

SAP. Of the thirteen, ten completed the study

according to the instructions provided to them. The

three who significantly digressed from the

instructions are not included in the analysis presented

in this paper. A summary of the demographic data for

the ten participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic data.

Gender Female: 3 Male: 7

Age 20-30: 8 > 30: 2

Experience

with SAP

< 2 months: 6

between 2 and 6 months: 4

Our experiment included two independent parts:

the Navigation study and the Association study. Each

of these studies included two component parts, one

involving an interactive visualization and one

involving SAP, as well as a questionnaire (see Figure

8). For each component part, participants were first

shown a two-to-four minute video tutorial

introducing the specific tool that they would be using.

After viewing the tutorial, they were asked to answer

a set of questions, each of which required the

participant to perform a specific task and, at the end

of each task, to enter their answer. The tutorials did

not provide answers to these task questions. Each

study ended with a questionnaire regarding the user’s

perceptions of the interfaces they used in the study

components.

Figure 8: Components of the user study.

As others have done before (Scholtz et al., 2010),

we use a mix of quantitative and qualitative measures

to capture data about the users’ performance and

experience. Correctness of responses and time spent

answering each question are used as proxy measures

for user effectiveness and efficiency with each of the

interfaces (see section 4.2.1). To allow direct

comparison between SAP and the visualizations, the

task questions in both the Navigation and

Associations studies were based on data that was

identical in structure but labelled differently. This

made it impossible for participants to reuse the

answers that they had found earlier.

The Navigation and Association questionnaire

responses, discussed in section 4.2.2, provide a

qualitative assessment of the users’ relative

satisfaction with the interfaces.

4.1.1 Navigation Study

Both the SAP and DTM components of the

Navigation study presented users with five pairs of

questions that required finding and selecting a task

with a specified name, and then finding a task related

(or in the case of DTM, linked) to the previous task,

based on the task name or description. Users were

given an option to write ‘skip’ when they were unable

to find the answer to the question after spending a few

minutes trying. The SAP transaction search

operations as well as the way to look for transactions

and transaction codes in DTM were demonstrated in

the Navigation tutorials (see Figure 7). All

participants had knowledge of the SAP menu gained

in the previous course work.

The DTM for the study was based on the SAP

usage logs from the course in which all participants

were enrolled. The DTM included 180 transactions

and 345 links. The number of different transactions

presented by SAP in a production system is, of

course, much larger than 180, but limiting the size of

the transaction set to a subset of transactions actually

used in an organization is a deliberate part of the

design of the DTM. However, the different sizes of

transaction sets have no bearing on the study results,

as it would be impossible to find the answers to the

task questions we presented in a reasonable time in

either the DTM or SAP without using the search

tools, whose performance is not noticeably affected

by the size of the transaction set.

Finding a task in DTM involved either using the

search interface or clicking directly on a task circle.

To verify that the correct task had been found,

participants had to report the task code that was

revealed when the task was selected. To find a task in

SAP, users had to either locate it in the Menu or use

SAP search transactions (SEARCH_USER_MENU or

SEARCH_SAP_MENU). Similarly to DTM, users had

to report the corresponding task code.

Part 1 -- Navigation study:

1.1 DTM Navigation component

• DTM tutorial (4 min.)

• 10 task questions

1.2 SAP Navigation component

• SAP Navigation tutorial (5.5 min.)

• 10 task questions

1.3 Navigation questionnaire (3 questions)

Part 2 -- Associations study:

2.1 SAP Associations component

• SAP ME1P report tutorial (2.5 min)

• 6 task questions

2.2 AM component

• AM tutorial (2.5 min)

• 6 task questions

2.3 Associations questionnaire (3

questions)

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

373

The transaction names in both the DTM and SAP

tasks were nearly identical, both based on SAP

transaction names. The task codes in DTM were

purposely different from the SAP ones to prevent

users from reusing the codes they discovered in the

SAP part of the Navigation study in their responses in

the DTM part.

4.1.2 Associations Study

The Associations study tasks asked participants to

answer six questions regarding three entities:

Vendors, Materials supplied by Vendors, and Plants

using the Materials. The questions required different

analyses of the data but did not substantially differ in

complexity. For evaluation in SAP, we prepared a

variant of the SAP Order Price History report (ME1P),

which summarizes data from purchase orders in a

textual form (see Figure 9). The AM component

visualized the same set of Materials, Plants, and

Vendors as the report but used different names. The

data included eight materials, eight vendors, and five

plants involved in approximately 24 purchasing

records. Each question asked the user to identify and

report a set of items; for example: “List vendor

numbers of all vendors that supply materials that are

used in Plant WD00.” The tutorial for AM

demonstrated basic features of the visualization; the

SAP tutorial briefly described the contents of the

report.

Figure 9: A snapshot of two records in an SAP Purchase

Order Price History Report used for comparison with AM.

To answer task questions using the AM required

that users select an appropriate item via clicking on it

or by entering its name in the search interface and

observing the linked items. The item names were then

entered by the users in the spaces provided for the

answers. To obtain the answers in SAP required

inspecting the entire report, a process that could be

simplified by the use of a selection function, available

via the Ctrl-F keyboard shortcut or by clicking on the

Find icon in the menu.

4.2 Analysis of Results

The analysis of user performance in the Navigation

and Associations studies between SAP and the

visualizations is presented next. The participants’

responses regarding the usefulness of the

visualizations, their preferences regarding the

visualizations versus SAP, and suggested

improvements are discussed in section 4.2.2.

4.2.1 Quantitative Findings

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results from the

Navigation and Association studies, respectively.

Table 2: Summary of the efficiency and effectiveness

results of the Navigation study.

SAP

Total

Time

(Sec)

DTM

Total

Time

(Sec)

SAP/

DTM

time

ratio

SAP

corr.

out of

10

DTM

corr. out

of 10

SAP/DT

M corr.

ratio

1 579 163 3.6 6 8 0.8

2 544 222 2.5 0 6 -

3 1266 346 3.7 8 10 0.8

4 615 208 3.0 2 10 0.2

5 455 200 2.3 6 10 0.6

6 482 245 2.0 8 10 0.8

7 1104 259 4.3 9 10 0.9

8 533 234 2.3 3 10 0.3

9 705 192 3.7 2 10 0.2

10 579 222 2.6 5 10 0.5

Ave 686 229 3.0 4.90 9.4 0.6

% correct answers

49

94

% perfect answers 0 80

Navigation study were at least twice as fast at

finding transactions in DTM compared to SAP. On

average, the SAP interface required users spend three

times as much time as with DTM. In terms of

correctness, none of the users provided correct

answers to all of the questions in SAP, whereas eight

out of ten participants had perfect responses when

using DTM. Overall, the SAP interface yielded a 49%

correctness rate, versus a 94% rate with DTM. ‘Skip’

answers, indicating the user had given up, are counted

as incorrect here. Out of 51 incorrect answers with

SAP, 29 were ‘skips.’ In the DTM category, there was

one ‘skip’ answer.

As shown in Table 2, all participants in the As

shown in Table 3 for the Associations study, users

came up with answers an average of 2.6 times faster

when using the Association Map. The correctness

achieved with the use of the SAP report was

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

374

approximately 67%, with two people out of 10

providing all correct answers. Using AM, correctness

was 90%, with five out of ten participants entering

perfect answers. There were no ‘skip’ answers with

SAP and one with AM.

Table 3: Summary of the efficiency and effectiveness

results of the Associations study.

SAP

Assoc

Time

(Sec)

AM

Time

(Sec)

SAP/AM

time

ratio

SAP

corr.

out

of 6

AM

corr.

out

of 6

SAP/

AM

corr.

ratio

1 373 240 1.6 5 6 0.8

2 507 191 2.7 3 6 0.5

3 622 293 2.1 6 6 1.0

4 606 78 7.8 4 5 0.8

5 280 175 1.6 1 5 0.2

6 320 90 3.5 5 5 1.0

7 351 150 2.3 6 6 1.0

8 353 206 1.7 2 5 0.4

9 621 428 1.4 3 4 0.8

10 246 193 1.3 5 6 0.8

Ave 428 205 2.6 4.00 5.40 0.7

% correct answers 66.7 90

% perfect answers 20 60

Overall, the results demonstrate that across 20

cases involving 10 users and two different tasks, the

interactive visualizations yielded greater (in 90% of

cases) or equally accurate responses and required less

time than SAP in all cases. The higher number of

‘skip’ responses in the SAP Navigation part indicates

the particular difficulty users experience in locating

transactions with this interface.

4.2.2 Qualitative Findings

After the participants completed the tasks in each of

the two studies, they were asked to respond to a short

questionnaire about their experiences. The three

questions asked after the Navigation study are shown

in Figure 10, while the three asked after the

Associations study are in Figure 11.

Figure 10: Navigation study questionnaire.

Navigation Study: Responses to the navigation

questionnaire revealed that participants were

generally pleased with DTM and typically preferred

it to SAP. In response to Question 1, eight of the 10

participants replied that they would use DTM. The

primary reason given was that it was much easier to

find transaction codes than with SAP because you can

see the connections between transactions.

Participants also commented that DTM is intuitive

and logical. Of the two dissenters, one said s/he would

try it but had difficulty getting overlapping names to

spread out. The other thought s/he would use it at first

but would then likely switch to searching with SAP

once s/he had more experience.

Figure 11: Associations study questionnaire.

In comparing DTM to SAP (Question 2), nine

participants strongly preferred DTM. Comments

included that it was much easier to use, faster for

searching, and more useful and intuitive. The one less

enthusiastic comment was that neither DTM nor SAP

are ideal for searching, but that DTM does provide

better visualizations of steps and how they are

connected.

Participants had many useful suggestions in

response to Question 3, including having DTM

remember and highlight the user’s prior searches,

spreading the transactions out more for easier

reading, and adding logical groupings of nodes (such

as production planning, inventory, etc.).

Associations Study: Responders to the associations

questionnaire were also pleased with AM. In response

to Question 1, the majority of participants

commented on how easy it was to use for finding

associated information. Seven would use AM with no

qualifications given, one would use it but would

prefer an excel report with pivoting, one would

potentially use it, and another expressed concern

about how crowded it might get when used with a full

production system. Other comments included how

well it organizes the information and how it “took

away the tedious scrolling that SAP required.”

The responses to Question 2 were all positive,

with eight participants noting that AM was much

1. Would you use the Dynamic Task Map for navigating to a

desired transaction, if it were embedded within an ERP

interface and if clicking on a transaction circle would open

the transaction? Why or why not?

2. How would you compare the Dynamic Task Map to the

way of finding transactions in SAP in terms of ease of use

and usefulness?

3. Do you have any suggestions for improving the Dynamic

Task Map interface?

1. Would you use the Association Map for answering

questions about plant-material-vendor associations if it

were embedded within an ERP interface? Why or why

not?

2. How would you compare the Association Map to the way

of finding the same information in SAP in terms of ease of

use and usefulness?

3. Do you have any suggestions for improving the

Association Map interface?

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

375

easier to use than SAP, one commenting on how it

saves time, and another on how it is clearer and less

“search-heavy.”

Some of the suggestions in response to Question

3 included preserving the view when the mouse

moves away from an association and making the drill-

down “sticky” so that the user can capture the

information more easily, automatic report

generation/file download from the selected

associations, and improved support for searching over

multiple fields.

5 DISCUSSION

The analysis of the data from this study shows that for

novice users performing common tasks, such as

finding transactions or associations among master

records, interactive visualizations considerably

decreased task completion time and increased

accuracy compared to traditional ERP interfaces.

Notably, participants were introduced to DTM and

AM at the time of the study, while the SAP interface

was already familiar to them through previous

coursework. The users’ greater success rate in our

experiment at completing the tasks with visual

interfaces that were previously unfamiliar to them

suggests that interactive visualizations may enable

novice users to complete more difficult tasks without

the extensive training and experience with the system

that would otherwise have been required.

The qualitative data analysis suggests that even as

users become more experienced with the system, they

may still benefit from interactive visualizations.

Visualizations presented here can incorporate more

advanced options, such as grouping transactions in

DTM together by business function and facilitating

easier data download from AM for report generation.

Such options would improve the fit between the user,

the business needs, and the interface capabilities,

which is an essential element of ERP implementation

success (Hong and Kim, 2002).

The results of the study presented here suggest

that interactive visualizations are one way that ERP

vendors can increase the usability of their products,

which is becoming more and more important in

today’s ERP marketplace (King, 2012). These

visualizations are more intuitive to learn and easier to

use and thus should reduce the need for extensive and

expensive training. The users’ improved perception

of the ERP system and greater confidence in their

ability to perform the necessary tasks with it would

lead to less resistance and increase acceptance of a

newly implemented system. Last, but not least, the

interactive interface would result in productivity

improvements by reducing the time it takes to

complete tasks and improving accuracy. As a result,

the need for re-work and the associated delays would

be minimized.

The main limitation of the study stems from the

fact that our visualizations were implemented as

standalone interfaces, while the SAP interfaces for

the same tasks were embedded in the context of a

larger system. Thus, some inefficiency in performing

tasks with SAP could be due to the users’ attention

being distracted by the numerous features of the

interface. Another limitation is the small number and

the uniform background of the study participants.

Although a larger, more diverse sample population

would provide a more complete assessment of the

benefits of interactive visualizations for different user

groups, our sample is appropriate for an initial

usability study targeted at novice users.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we advance ERP usability research by

investigating the use of interactive visualizations for

navigation and association-related tasks in enterprise

systems. Our results showed that novice users

performed those tasks faster and at least as accurately

when using DTM and AM visualizations than when

using SAP. These results empirically corroborate the

view expressed by users in surveys (Lambeck et al.

2014a, 2014b) that useful visualizations decrease the

complexity of ERP interfaces, enabling more

productive use of the system. Users also

overwhelmingly preferred the visual interfaces to the

SAP alternatives.

In future work, we plan to fine-tune and enhance

the existing visualizations based on feedback from the

study. We will use the improved interfaces to

investigate the impact of different features on user

performance and user perceptions in more detail and

with a larger sample population.

REFERENCES

Babaian, T., Lucas, W., Li, M. 2015. Modernizing

exploration and navigation in enterprise systems with

interactive visualizations. Human Interface and the

Management of Information. Information and

Knowledge Design, (HCII 2015), Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, Springer, vol. 9172, 23-33.

Babaian, T., Lucas, W., Xu, J., Topi, H. 2010. Usability

through system-user collaboration: design principles

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

376

for greater ERP usability. In DESRIST'10, the 5th

international conference on Global Perspectives on

Design Science Research, Robert Winter, J. Leon Zhao,

and Stephan Aier (Eds.). Springer-Verlag, Berlin,

Heidelberg, 394-409.

Cooprider, J., Topi, H., Xu, J., Dias, M., Babaian, T., Lucas,

W., 2010. A collaboration model for ERP user-system

interaction. In HICSS’10, the 43rd Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences, 1-9.

Drobik, A., 2015. IT Market Clock for ERP Platform

Technology, 2015. Gartner.

Ganly, D. , Montgomery, N., 2015. Hype Cycle for ERP,

2015. Gartner.

Hipp, M., Mutschler, B., Reichert, M., 2012. Navigating in

complex business processes. In DEXA’12, the 23rd

International Conference on Database and Expert

Systems Applications, Part II, Springer, 466-480.

Hipp, M., Mutschler, B., Reichert, M., 2014. Navigating in

Process Model Repositories and Enterprise Process

Information. In RCIS’14, the 8th International

Conference on Research Challenges in Information

Science, IEEE, 1-12.

Hong, K. K., & Kim, Y. G., 2002. The critical success

factors for ERP implementation: an organizational fit

perspective. Information & Management, 40(1), 25-40.

Hurtienne, J., Prümper, J. Rötting, M., 2009. When

enterprise resource planning needs software

ergonomics: Some typical scenarios. In IEA’09, the

17th World Congress on Ergonomics

King, R., 2012. SAP Owns Up to Usability Problem. The

Wall Street Journal CIO Report, August 2, 2012.

Krigsman, M., 2010. Understanding Lumber Liquidators'

ERP failure. ZDNet, November 11, 2010.

Lambeck, C., Fohrholtz, C., Leyh, C., Šūpulniece, I.,

Müller, R., 2014a. Commonalities and contrasts: An

investigation of ERP usability in a comparative user

study. In ECIS’14, 22

nd

European Conference on

Information Systems.

Lambeck, C., Muller, R., Fohrholz, C., Leyh, C., 2014b.

(Re-) Evaluating User Interface Aspects in ERP

Systems – An Empirical User Study. In HICSS’14, 47th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

396-405, IEEE.

Lucas, W., Babaian, T. 2012. Implementing design

principles for collaborative ERP systems.

In DESRIST'12, the 7th international conference on

Design Science Research in Information Systems:

advances in theory and practice, Ken Peffers, Marcus

Rothenberger, and Bill Kuechler (Eds.). Springer-

Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 88-107.

Myers, B., 1994. Challenges of HCI design and

implementation. Interactions, 1(1), 73-83.

Parks, N. E., 2012. Testing & quantifying ERP usability. In

RIIT’12, 1

st

Annual Conference on Research in

Information Technology, 31-36.

Parush, A., Hod, A., & Shtub, A., 2007. Impact of

visualization type and contextual factors on

performance with enterprise resource planning systems.

Computers & Industrial Engineering, 52(1), 133-142.

Pike, W.A., Stasko, J., Chang, R., O'Connell, T.A., 2009.

The science of interaction. Information

Visualization, 8(4), 263-274.

Rettig, C., 2007. The trouble with enterprise software.

Sloan Management Review, 49(1), 21-27.

Scholtz, B., Cilliers, C., Calitz, A., 2010. Qualitative

techniques for evaluating enterprise resource planning

(ERP) user interfaces. In SAICSIT’10, Annual Research

Conference of the South African Institute of Computer

Scientists and Information Technologists, 284-293.

Topi, H., Lucas, W. & Babaian, T. 2005. Identifying

usability issues with an ERP implementation. In

ICEIS’05, 7th International Conference on Enterprise

Information Systems.

van deer Aalst, W.M.P., 2011. Process Mining: Discovery,

Conformance, and Enhancement of Business

Processes. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Yi, J.S., Kang, A.K., Stasko, J.T., Jacko, J.A., 2007.

Toward a Deeper Understanding of the Role of

Interaction in Information Visualization. In IEEE

Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics,

13(6), 1224-1231.

Evaluating Interactive Visualizations for Supporting Navigation and Exploration in Enterprise Systems

377