OER-based Lifelong Learning for Older People

Rosa Navarrete

1

and Sergio Luján-Mora

2

1

National Polytechnic School, Department of Informatics and Computer Science, Quito, Ecuador

2

University of Alicante, Department of Software and Computing Systems, Alicante, Spain

Keywords: Open Educational Resources, OER-based Learning, Lifelong Learning, Digital Literacy, Web Accessibility,

Older People.

Abstract: The Open Educational Resources (OER) are becoming a promising contribution to the enhancement of

learning opportunities for all people worldwide. The OER involve educational digital content that have been

released under an open license for free use or adaptation. The use of OER in formal and non-formal

educational environments is known as OER-based learning. On the other hand, population ageing is currently

recognized as a global issue of increasing importance with many implications for the economic development

of countries. The access to learning by these people, in particular, the acquisition of the technical competence

for using information and communication technologies, can improve their social involvement. This research

aims to check the feasibility of using OER in lifelong learning programs for older people. Considering that

these people have disabilities due to ageing, this research conducted a searching and validation process to

verify the relevance and accessibility of OER to be used on a specific learning program oriented to digital

literacy for older people. Finally, this research presents an accessibility validation based on barriers that older

people face for using OER. Further, this work highlights the issues that hinder the OER-based learning

programs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Currently, there is an increasing interest in Open

Educational Resources (OER) as a complement to

enhance education and knowledge access worldwide

to all people. This inclusive vision requires

considering people with particular learning

requirements such as older people.

At the present, the proportion of people aged over

60 years is growing in almost all countries. The older

people experience a decreasing of their physical,

sensory and cognitive capabilities. Therefore, the

issues of impairment and disability will become

increasingly significant in all areas of human life,

including education.

In such context, this work explores the feasibility

of OER usage in a lifelong learning program for

digital literacy aimed at older people through a

process of searching resources and validating their

relevance to the educational purpose and their

accessibility characteristics.

The outcomes of this research highlight the issues

related to the use of OER to support lifelong learning

as well as the improvements required in OER design

to enable their use for older people.

The structure of this paper is as follow. Section 2

presents the theoretical framework; Section 3

addresses the process of searching OER and their

validation for relevance and accessibility; Section 4

presents the results of the searching and validation of

OER; and, in the final part of this paper, the outcomes

of this research are discussed.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 OER-based Learning

The term OER coined at UNESCO (2002) refers to

any digital content with a teaching-learning purpose

that is released under an open license to allow their

free use or repurposing. OER can be full courses or

course materials in a diversity of formats such as

audio, video, text, PDF, or HTML (Atkins et al.,

2007).

The OER-based learning is the use of OER to

support learning in different educational

environments such as higher education, e-learning,

lifelong learning programs, and self-learning (De

388

Navarrete, R. and Luján-Mora, S.

OER-based Lifelong Learning for Older People.

In Proceedings of the 8th Inter national Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2016) - Volume 2, pages 388-393

ISBN: 978-989-758-179-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Langen and Bitter-Rijkema, 2012; OECD, 2007a).

2.2 Web Accessibility and Older People

According to the World Population Ageing report

(United Nations, 2013), the world's population is

aging at an accelerated rate. People over 60 years old

represent 12% percent of the current global

population, and by 2050, that number will rise to

21%. Older people experience age-related disabilities

such as decreasing of their physical, sensory and

cognitive capabilities (WHO, 2011). Consequently,

the impairments that hinder them from using the web

are related to gradual hearing loss; vision decline, loss

of color perception and contrast sensitivity;

restriction of hands movement or restricted hand

dexterity, and cognitive decline (W3C, 2008a).

The web accessibility enables that people with

disabilities can overcome the barriers to an effective

use of the web (W3C, 2005). The web accessibility is

achieved through the application of accessibility

guidelines. Currently, the Web Content Accessibility

Guidelines, WCAG 2.0 (W3C, 2008b) is the most

widespread standard for web accessibility. This

standard is a set of 12 guidelines structured under four

principles: Perceivable, Operable, Understandable

and Robust. Each guideline has a set of success

criteria associated with a level of conformance.

2.3 Lifelong Learning and Digital

Literacy

Lifelong learning refers to the learning that takes

place at all stages of life, preferably in adult life, in

both formal and non-formal environments (Green,

2002). Under the premise of lifelong learning, the

access to learning for older people becomes a

motivation for carry out intellectual tasks and

consequently to enhance their cognitive abilities

(Xavier et al., 2014).

Moreover, the European Parliament and the

European Council, in their Recommendation on key

competences for lifelong learning (2006), emphasizes

that digital literacy should be extended to older adults

to improve their quality of life.

Digital literacy refers to the acquisition of the

technical competence for using information and

communication technologies for employment,

learning, self-development and participation in

society. It also implies the ability to perform tasks

effectively in a digital environment (Jones-Kavalier

and Flannigan, 2006).

For the scope of this research we have adopted the

common skills of digital literacy at basic level

(UNESCO, 2011) which correspond to these topics:

Basic Computer Skills. This topic refers to the

fundamentals of computing, explains the

components of a computer, and explores

operating system basics.

Internet and World Wide Web. This topic explains

how to connect to the Internet, use search engines,

browse web pages, use e-mail, and register on a

website.

Productivity Programs. This topic explores the

most common productivity software applications

(word processing, spreadsheet, and presentation

software) at basic level.

3 PROCESS FOR SEARCHING

AND VALIDATING OER

Some studies highlight the potential of the OER-

based learning as an efficient way to promote lifelong

learning (Kumar Das, 2011; Misra, 2012; OECD,

2007b). However, another study argues that

compared with other educational sectors, adult

learning is the sector with the lowest level of OER

development (Minguillón et al., 2009), while a study

of European Commission points out some obstacles

related to the applicability of OER in adult education

(Falconer et al., 2013).

In this work we propose a process for searching

and validation of OER that enables the selection of

suitable resources to be used by older people in a

digital literacy learning program. The outcomes of

this work could contribute to the discussion in this

context.

3.1 Searching OER

The searching of resources can be a time consuming

activity because of the vast amount of available OER

repositories (Hatakka, 2009). Considering that the

scope of this research is related to the accessibility of

the resources, we have selected two of the large-scale

OER websites that have made major strides in this

field: “MERLOT” (https://www.merlot.org/) and

“OER Commons” (https://www.oercommons.org/)

(Navarrete and Luján-Mora, 2013; Navarrete and

Luján-Mora, 2015).

In addition, it is important to define the main

parameters for searching: the topics and the format

of the resources. The search has been based on

various terms related to the topics proposed above in

section 2.3 Digital Literacy. Regarding the formats,

this research has prioritized HTML due to the

OER-based Lifelong Learning for Older People

389

richness of multimedia resources that can be included

in web pages and its independence of a specific

software for visualization.

3.2 Validating OER

The validation covers the relevance of the resources

for the purpose of the digital literacy program as well

as the accessibility of resources that enable their use

for older people.

3.2.1 Relevance Validation

The relevance of a resource is related to quality

aspects that impact on its educational purpose

(Camilleri et al., 2014). For this work, we have

considered that the relevance of OER relies on these

aspects:

Educational value that includes the relevance of

the content concerning the learning purpose, the

accuracy and the up to date content.

License restrictions about the use and reuse of the

resource. The reference adopted is the open

licensing framework “Creative Commons” (CC)

which is used by MERLOT and OER Commons.

These copyright licenses provide a standardized

way to give the public permission to share and use

the resources, therefore, it is possible to know

whether the resources can be used for free or can

be reused if required.

3.2.2 Accessibility Validation

The accessibility validation is performed through a

heuristic evaluation of the accessibility of the

resources to be usable by older people, supported by

the “Barrier Walkthrough” method (Brajnik, 2006).

This method is based on the identification of the

possible barriers that people with disabilities faced in

web design depending on their disability, the type of

assistive technology being used, the failure mode

(that is the activity/task that is hindered and how it is

hindered), and the design characteristics that produce

the barrier. Furthermore, this method proposes some

potential barriers for different disabilities.

In order to define the barriers for older people, this

research has also reviewed the set of

recommendations on designing web pages to be

usable by older people, proposed by the project Web

Accessibility Initiative: Ageing Education and

Harmonisation (WAI-AGE, 2009) from the European

Commission and theW3C.

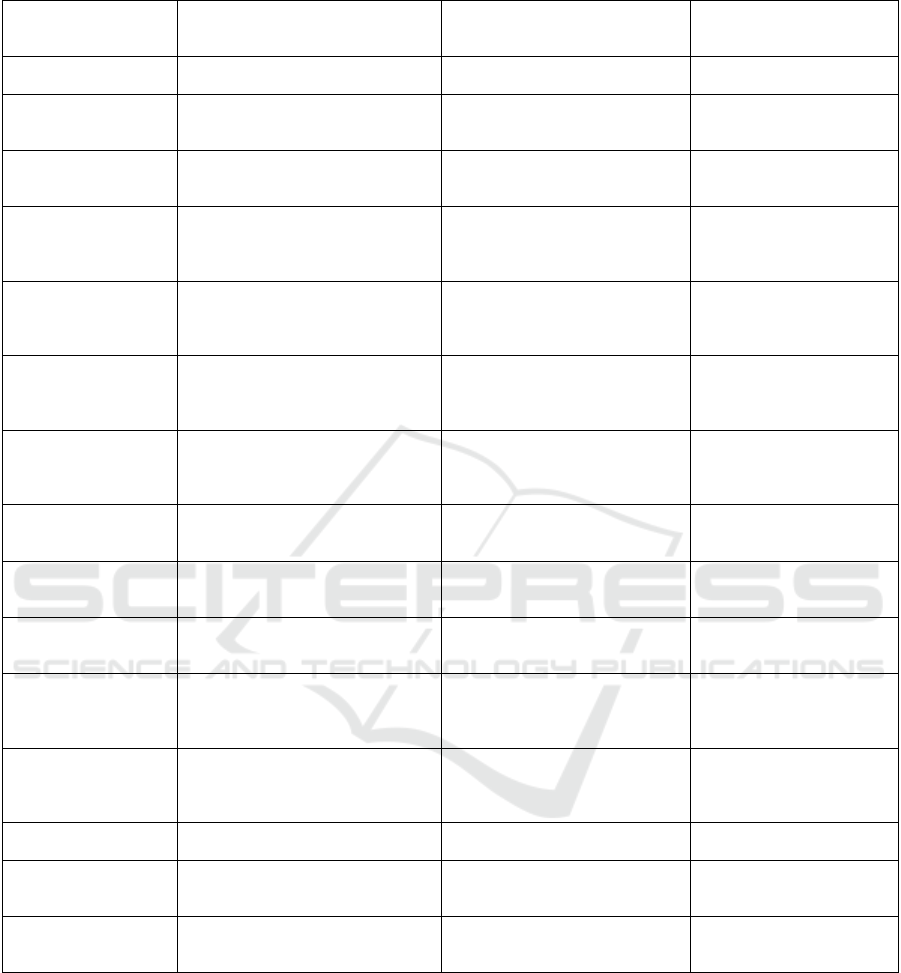

Based on the above, Table 1 presents the

accessibility barriers for older people that have been

considered in this research. The table also includes for

each barrier: its cause, the failure mode, and the

guideline or success criteria corresponding with

WCAG 2.0 concerning to this barrier. Because of the

lack of space, only the most common barriers for

older people are included.

Further, the accessibility evaluation has been

performed by means of using automated tools

complemented with expert human judgment,

according to what has been done in a previous work

of the authors (Navarrete and Luján-Mora, 2015). The

accessibility evaluation has verified the presence of

these barriers in the resources.

4 RESULTS

The OER websites do not have a unique standard for

content categorization, which implies that the

searching of resources is particular for each one.

Therefore, to get a preliminary approach to the

potential OER that meeting the needs of this research,

the search has based on “keywords” or “exact

phrases” related to topics described previously.

Further, to improve the searching results, the

“software products”, have been also included in the

searching. Only the Microsoft software products have

produced results, as presented in Table 2. This table

also presents the list of keywords or exact phrases, the

number of resources obtained from each OER website

(“# resources” column), and the number of resources

that have been validated as relevant for this project

(“# relevant” column).

These websites have presented some issues in the

search interfaces. For example, the lack of pagination

to display the results, and the inability of setting the

number of results to be displayed per page. These

problems could become barriers for older people.

4.1 Results of Relevance Validation

As presented in Table 2, after the evaluation of the

relevance of the resources based on their educational

value and license restriction, the number of suitable

resources has been reduced significantly.

The resources that were qualified as relevant had

HTML format combined with PDF documents or

video material.

These have been the main problems with respect

to the educational value:

The content of the resources was not intended to

teach the use of a software product, instead, it was

about the application of the software to another

purpose (e.g. the use of Excel in medical statistics)

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

390

Table 1: Barriers related to web accessibility for older people.

Barrier Cause Failure mode

WCAG 2.0

Success criteria and/or

Guideline

Text cannot be resized

Use of absolute units in CSS to

specify font size.

The user might not be able to

increase the font size of the text.

1.4.4 Resize text

1.4.8 Visual Presentation

Color is necessary

The color is used as the sole mean to

distinguish two or more different

information items.

The user has inability to perceive

colors (as those users with normal

vision capabilities).

1.4.1 Use of color

Insufficient visual

contrast

The colors used for foreground

material against a background have

insufficient contrast.

The user experiences problems

recognizing the foreground items.

1.4.3 Contrast (Minimum)

1.4.6 Contrast (Enhanced)

Functional images

lacking text

The page contains functional images

(clickable links, form buttons, image

maps) that do not have alternative

equivalent text.

The user would not be able to

enlarge the images (if not using a

screen magnifier). He would not be

able to interpret them.

1.1.1 Non-text content

1.4.5 Images of text

Dynamic menus in

JavaScript

When the user moves the focus of

interaction with an element, a menu

drops down in a given area of the

page.

The menu could easily be located

outside the visual field of the user,

who will not be able to use it at all

(when using a screen magnifier).

2.1.1 (2.1.3) Keyboard 4.1.2

Name, Role, Value

Too many links

The page contains too many links that

are not well organized in clearly

labelled groups.

A large number of links requires

that users perform a scanning them

all before deciding if there is one

that is worth following.

2.4.10 Section headings

Skip links not

implemented

The page does not allow the user to

jump directly to the content (skipping

over breadcrumbs, search boxes,

global navigation bars).

The user has no way to quickly set

the focus of interaction on the page

content.

2.4.1 Bypass blocks

Ambiguous links

The links with labels are ambiguous.

The same text is used to represent

different URLs.

The user could activate the wrong

link by mistake.

2.4.1 (2.4.9) Link purpose

Mouse events

The page is based on JavaScript

functions invoked through event

handlers (mouse-oriented).

It is probably that user prefers using

the keyboard rather than the mouse.

2.1.1 (2.1.3) Keyboard

Keyboard traps

The page contains components that

lock the user once moves the

keyboard focus on them.

The user cannot use the keyboard

rather than the mouse for certain

activities.

2.1.2 No Keyboard Trap

Forms with no label

tags

The page contains a form whose

controls are not marked up with

LABEL tag and FOR attribute.

Some controls (radio buttons and

checkboxes) have a clickable area

that is very small. The user will

struggle to hit them correctly.

2.4.7 Focus visible

1.3.1 Info and relationships

Video with no captions

A multimedia file with a video or an

animation that has no caption (or

textual description).

The older people have problems to

perceive the auditory information

because of their hearing loss.

2.4 Time-based Media

Missing

synchronization

The caption or textual description are

not synchronized to the video.

The user has difficulties to perceive

the information.

1.2.2 Captions (Prerecorded)

Complex text

The text is complex to read

(complexity of the sentences,

acronyms).

Older people require great effort to

understand the text.

3.1.3 Unusual word

3.1.5 Reading level

Complex site

The website has a complex

organization (content grouping and

content relationships)

Older people require great effort to

understand the content and in

navigating through it.

2.4.5 Multiple ways

The content of these resources was aimed at

computer professionals, so, these were not

appropriate to a basic level.

The content of these resources did not correspond

to current technologies.

The content of these resources did not correspond

to the associated keywords.

With regard to the licenses of the resources, some of

them were not qualified as relevant because their

licenses did not allow the free use. For example, some

resources, mostly online courses, required payment

for student registration. The accepted resources had

Creative Commons licenses based on these

conditions: BY (Attribution), NC (NonCommercial),

SA (Share-Alike), and ND (No Derivative works) and

with these licenses (CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC-

SA), or a declaration to allow their free use.

OER-based Lifelong Learning for Older People

391

Table 2: Number of resources in OER websites.

Keyword or

exact phrase

for searching

Number of resources

OER Commons MERLOT

# resources

#

relevant

# resources

#

relevant

Digital

literacy

87 2 74 1

Basic

computer

skills

50 3 15 1

Using the web 0 0 66 2

Word

processor

5 1 26 0

Spreadsheet 246 1 113 4

Presentation

software

5 0 13 0

Microsoft

word

51 1 102 1

Excel 441 2 278 0

Power Point 356 3 126 0

Additionally, the searching results showed that

some resources were available on both websites, OER

Commons and MERLOT. Also, some resources

included more than one of the topics of interest.

4.2 Results of Accessibility Validation

Due to the lack of space, the results of the heuristic

accessibility validation of each resource cannot be

exposed. However, the most important general results

are presented below.

We have found two resources accessible for older

people. Fortunately, these web courses encompass

almost all the content required for this program on

digital literacy.

All resources that include videos have failed for

accessibility because they did not have captions or

transcripts. The subtitles for all videos hosted in

YouTube have been produced by the speech

recognition technology of YouTube. Therefore,

these were not accurate. Thereby, the older

people who experience hearing loss could have

understanding issues of the content exposed in

videos.

None of the resources in HTML format enables

text resizing as a user preference. This restriction

can hinder that older people with vision

impairments be able to read the content.

In some resources, the HTML pages contain

mouse-oriented events. The people who use the

keyboard, instead of the mouse for interaction,

cannot detect these events. This can be the case of

older people with hand dexterity issues that prefer

the use of the keyboard.

In some resources, the HTML pages have issues

of color contrast. For older people, their loss of

color-contrast perception could hinder the

recognition of the foreground items.

5 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

WORK

A frequent criticism for the adoption of OER in

learning programs is their lack of adjustment to

context-specific needs. Indeed, the biggest obstacle

to the adoption of OER in the learning program

proposed in this research has been finding the

resources that meet the requirements, regarding

contents and particular needs, for example,

accessibility of the resources.

The searching of resources has been exhaustive

and has demanded the verification of a large set of

“keywords” and “exact phrases” to achieve

significant results. After this, it has been necessary to

review the relevance of several hundreds of resources

for this learning program. A major issue has been the

inconsistency between the content of the resources

and the keywords or phrases associated with them.

Moreover, we have found that some online courses

did not correspond to the “open” philosophy because

they demanded a registration payment.

Also, the interfaces for browsing the searching

results, in OER Commons and MERLOT, have been

inefficient for several hundreds of results. For

example, in OER Commons, the pagination of search

results is not enabled; although, it is possible to

establish the number of results to be displayed

(maximum 100). The page shows the option “load

more” to see more results, so, the visualization with

the vertical scroll of the page becomes a problem.

After the selection of relevant resources and their

accessibility validation, we have found two resources

that cover almost all the topics for the digital literacy

program and are suitable to be used by older people.

These resources are web-based courses provided by

DigitalLearn.org and the Connecticut Distance

Learning Consortium.

Based on the outcomes of this research we can

argue that despite the broad availability of resources

and the inclusive vision of OER initiatives, the

accessibility characteristics have not been addressed

as quality requirements of these resources.

As a final reflection, the most significant barrier

to wider adoption of OER in this type of learning

programs is the user perception of the time and effort

required to find and evaluate the resources. If a user

CSEDU 2016 - 8th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

392

is an older adult, the task of search and selection of

resources can be discouraging.

In our future work, we will plan to develop a

process to search resources for specific needs that

include accessibility characteristics. This process

will consider the perspective of older people and

people with mild disabilities to increase the reuse of

OER.

REFERENCES

Atkins, D., Seely Brown, J., and Hammond, A. L., 2007. A

review of the Open Educational Resources (OER)

Movement: Achievements, Challenges and New

Opportunities. [Online] Available at:

http://goo.gl/okvCkU [Accessed June 09 2015].

Brajnik, G., 2006. Web accessibility testing: When the

method is the culprit. In: Computer Helping People

with Special Needs. Springer, pp. 156-163.

Camilleri, A. F., Ehlers, U. D., and Pawlowski, J., 2014.

State of the Art Review of Quality Issues related to

Open Educational Resources (OER). JCR Scientific and

Policy Reports, pp. 2-43.

De Langen, F. & Bitter-Rijkema, M., 2012. Positioning the

OER Business Model for Open Education. European

Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, Volume I,

pp. 1-13.

Falconer, I., McGill, L., Littlejohn, A., and Boursinou, E.,

2013. Overview and analysis of practices with open

educational resources in adult education in Europe

(OER4Adults). JRC Scientific and Policy Reports, pp.

1-82.

Green, A., 2002. The Many Faces of Lifelong Learning:

Recent Education Policy Trends in Europe. Journal of

Education Policy, 17(6), pp. 611-626.

Hatakka, M., 2009. Build It and They Will Come? –

Inhibiting Factors for Reuse of Open Content in

Developing Countries. EJISDC, 37(5), pp. 1-16.

Jones-Kavalier, B. R., and Flannigan, S. L., 2006.

Connecting the digital dots: Literacy of the 21st

century. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29(2).

Kumar Das, A., 2011. Emergence of open educational

resources (OER) in India and its impact on lifelong

learning. Library Hi Tech News, 28(5), pp. 10-15.

Minguillón, J., Rodríguez, M., and Conesa, J., 2009.

Extending learning objects by means of social

networking. In Advances in Web-Based Learning.

Berlin: Springer, pp. 220-229.

Misra, P. K., 2012. Open Educational Resources: Lifelong

learning for engaged ageing. In Collaborative Learning

2.0: Open Educational Resources. IGI Global, pp. 287-

303.

Navarrete, R. and Luján-Mora, S., 2013. Accessibility

considerations in Learning Objects and Open

Educational Resources. Proceedings of the 6th

International Conference of Education, Research and

Innovation. Seville - Spain, pp. 521-530.

Navarrete, R. and Luján-Mora, S., 2015. Evaluating

accessibility of Open Educational Resource website

with a heuristic method. Proceedings of the 9th

International Technology, Education and Development

Conference. Madrid - Spain, pp. 6402-6412.

OECD, 2007a. Giving Knowledge for Free: The

Emergence of Open Educational Resources,

Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development.

OECD, 2007b. Qualifications Systems Bridges to Lifelong

Learning, Organization for Economic Co-operation

and Development.

UNESCO, 2002. Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware

for Higher Education in Developing Countries: Final

report, Paris, France.

UNESCO, 2011. Digital Literacy in Education. [Online]

Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0

021/002144/214485e.pdf [Accessed July 07 2015].

United Nations, 2013. World Population Ageing, [Online]

Available at http://goo.gl/xPZYgg [Accessed July 06

2015].

W3C, 2005. Introduction to Web accessibility. [Online]

Available at http://goo.gl/dvnZfH [Accessed October

06 2015].

W3C, 2008a. Web Accessibility for Older Users: A

Literature Review. [Online] Available at:

http://www.w3.org/TR/wai-age-literature [Accessed

October 06 2015].

W3C, 2008b. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

(WCAG) 2.0. [Online] Available at:

http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/ [Accessed July 06

2015].

WAI-AGE, 2009. WAI Guidelines and Older Web Users:

Findings from a Literature Review. [Online] Available

at: http://www.w3.org/WAI/WAI-AGE/comparative.

html [Accessed October 16 2015].

WHO, 2011. Global Health and Aging, U.S [Online]

Available at: http://goo.gl/NEzFM3 [Accessed October

16 2015].

Xavier, A., D’Orsi, E., D’Oliveira, C. & Orrell, M., 2014.

English Longitudinal Study of Aging: Can Internet/E-

mail Use Reduce Cognitive Decline? The Journals of

Gerontology, Series A: Medical Sciences, 69(9), pp.

1117-1121.

OER-based Lifelong Learning for Older People

393