Localized Tech Parklets

A Concept for a New Urban Commons

Ratan J. Batliboi

1

, Bipin Pradeep

2

, Ranjani Balasubramanian

1

, Kanaka Thakker

1

, Prasun Agarwal

2

and Rakesh Trivedi

2

1

Ratan J. Batliboi Consultants Private Limited, 400012, Mumbai, India

2

Gaia Smart Cities, Mumbai, India

Keywords: Urban Commons, Smart Spaces, Participatory Urban Design.

Abstract: Urban commons were traditionally defined as commonly owned environmental resources – forests, rivers,

fisheries or grazing land that were shared, used and enjoyed by all. Commons were then adapted to include

public goods and services, such as public spaces, marketplaces, public education, health and infrastructure

that allow societies to function. Today, with the proliferation of technology and in the context of Smart

Cities, we explore the concept of a highly localized Technology based Parklet as a part of the new Urban

Commons in a suburb of Mumbai, Matunga.

1 INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW

URBAN COMMONS

The term “commons” comes from the reference to

commonly accessible sustenance resources in

England in the middle ages- mostly in the form of

arable land, water and forests. They represented a

minimum level of lawful and inalienable access to

resources that would ensure basic survival of all

citizens. With a rapidly growing urban population,

urban commons have become “synonymous with a

range of public spaces including lakes, parks, streets,

wetlands and forests”. (Unnikrishnan, 2013)

Although these spaces are usually owned and

managed by the state, diverse groups of citizens and

communities carve out their own access and

relationship with them both formally and informally.

Today, we are in the midst of the digital age, the

age of networked global cities and information

technology. Developing countries like India have

leapfrogged into the technological age, even as

many challenges of basic development persist.

Technology and access to technology therefore,

become critical in order to be inclusive and equitable

in the economic, social and lately even institutional

processes that determine the growth of these nations.

1.1 Bridging the Digital Divide

In 2015, India launched a 100 Smart Cities Scheme,

as a guiding vision for the urban development of a

country of 1.2 billion people. A fundamental factor

in the Smart Cities vision is the application of a wide

range of electronic and digital technologies to

development, infrastructure and governance. At a

macro level, while access to information (Internet) is

reported to increase GDP’s of counties, at the

ground level its sweeping impact on individual

growth and prosperity is slowly gaining mainstream

recognition. (McKinsey, 2016)

In India, the proliferation of internet has been

exponential. Today, India has the second largest

number of mobile phone users in the world.

However, with respect to internet usage, the

percentage share of internet users stands at 29%

largely from urban centres. With increasing

opportunities and services moving to an online

platform, the technological divide creates inequity

not just in terms of communication but also in terms

of opportunities for entrepreneurship and

livelihoods, access to essential services and financial

platforms.

This pressing need in ensuring inclusion in our

technological leapfrogging has been articulated in

the National Telecom Policy of 2012 which

recognises that in spite of the economic and

technological progress, the digital divide in India

continues to be significant and that the ability of the

rural and urban poor to benefit from technology

needs to be enhanced. The policy goes so far as “To

Batliboi, R., Pradeep, B., Balasubramanian, R., Thakker, K., Agarwal, P. and Trivedi, R.

Localized Tech Parklets - A Concept for a New Urban Commons.

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2016), pages 71-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-184-7

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

71

recognise telecom, including broadband connectivity

as a basic necessity like education and health and

work towards ‘Right to Broadband’”. (DoT, 2012)

It becomes essential, then, to consider that access

to the realm of digital and information technology,

just like access to public space and utilities is

essential to ensure equity in our growth story. This

project attempts at modeling precisely such public

access to space and information technology in a

sponsored, open and replicable format, through on

ground engagement with a community. The model

we propose takes into consideration the dense

conditions of Indian urbanity, and the dynamic

natures of our cities to create Tech parklets. These

new parklets could be more inclusive of the urban

poor or of those without access to the Internet,

thereby reducing the digital divide in the population.

The objective of this work is to provide a

prototypical design for a Technology Parklet as part

of the new urban commons. It aims at creating a

model for technology based parklets which can

become a part of our urbanscape by coupling urban

design concepts with new technology trends and a

viable and sustainable business/operational model.

This paper elaborates the concept of the tech parklet

as a social, economic, design and technological

model of new urban public spaces, and briefly

speaks about it in the context of a neighbourhood in

Mumbai called Matunga where the first prototype is

being designed.

2 APPROACH

The project was born out of an interdisciplinary

effort between the urban design cell of RJB-CPL

and the technology firm Gaia. The collaboration

aims at approaching the ongoing efforts of building

Indian Smart Cities not just through a technological

lens but also by finding ways to combine smart

technologies with sustainable innovations in urban

design and planning.

The idea of tech parklets was based on our

interventions in public spaces at various scales,

where we identified the current need to amalgamate

space with accessible technology. Our approach to

the project was to first identify the various contexts

in which such an intervention would be feasible,

followed by intensive spatial and social studies to

identify the specifications of the parklet.

The prototype is designed with a number of

technical and spatial modules which can be used in

permutations and combinations according to

contextual and circumstantial needs. An

overreaching approach to designing these tech

parklets is citizen engagement within a participatory

framework for co-design. This is an integral part of

embedding the parklet within a community or

neighbourhood and it will maintain the bottom up

and open nature of the concept.

This idea is centred at the intersection of four

themes:

Innovative Urban Design: Providing a

design model to use in the context of city and area

dynamics, and accommodating the diversity of

citizen needs in a user friendly environment. The

design would aim to promote social interactions and

would be inclusive by nature.

Digital Technologies: The Technology

elements, both Hardware and Software with new

techniques and localized services that should be

provided for unleashing the potential of the parklet,

ensuing citizen engagement and digital inclusion.

Sustainable Operational Innovation: Since

management is a key parameter for the performance

of public projects, identifying the localized

institutions and actors and building capacity among

them will ensure that the tech parklet can be

operationally feasible and sustainable. This will be

crucial to the longevity of the system.

Localization: In order to be accessible and

interactive, the tech parklets need to respond to local

contexts, cultures and user patterns. Therefore, the

tech parklet is modelled along the lines of existing

traditional Indian spaces of urban social interaction.

In the case of our prototype which is being

developed in Matunga, we are following a

participatory urban design approach, where we have

engaged the neighbourhood organizations and

residents in generating collective urban action. The

process of designing the tech parklet therefore, takes

place by engaging these local actors in identifying

their own requirements, and in setting up

sponsorship and operational mechanisms to sustain

the parklet.

The aim of our exercise of designing the tech

parklet at various locations and critically analyzing

the intervention is to eventually compile a handbook

which will provide the necessary know-how to allow

local actors to take up self-made tech parklets as

community interventions in public space.

3 EVOLUTION OF THE

PARKLET

Arising from tactical bottom up urban design

SMARTGREENS 2016 - 5th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

72

Figure 1: Images of Park(ing) Day (RebarGroup, 2016).

practice, the parklet as a concept was an attempt at

low-cost conversion of small and underutilized

residual spaces originally devoted to cars, into

spaces for the passive or active recreation of people.

The idea of the parklet in its current form grew from

Rebar’s ‘Park(ing) Day’ initiative in San Francesco-

an idea that has now been adopted as an annual

event in cities across the world. (RebarGroup, 2016)

Park(ing) day encourages citizens to create

temporary, one day installations intended to reclaim

public space and create pockets of social interaction

within the city in a do-it-yourself, bottom up

movement.

The basic idea encourages citizens to recognize

streets as public spaces and to determine need based

public functions that the space could be used for.

Other than providing alternate spatial visions,

Park(ing) Day also questions the normative

boundaries of privatization of public space and

citizen presence in public space.

In our current context, we are looking at the

concept of a parklet, as a model for a low cost,

replicable unit for public access points to

information technology. In addition to being a space

of active engagement, it could benefit local

businesses, residents, and visitors by providing

much needed public spaces which attract customers

and foster community conversation.

4 LOCALISING THE TECH

PARKLET

In the context of Mumbai, interventions like the

‘vachnalays’ or public reading rooms have been

popular but continue to be used today only by a

certain age group of people, mainly the senior

citizens. Vachanalaya is a Marathi term which

means reading room. These are located in public

spaces and provide a range of newspapers and

magazines which can be accessed for free by the

public. Vachanalayas also often turn into lively

spaces of conversation and discussion. The

‘vachnalays’ constitute a healthy platform for

discussion and debate on current affairs and

encourage a certain knowledge based social

interaction. With the spread of technology and smart

phones, the younger generation refrains from using

these spaces, and the once prevalent urban platforms

are now becoming scarce.

Another colloquial form of localized public

spaces is temporary shaded seating areas near small

roadside shrines. Such “mandals”, are often used as

conversation spaces by local residents and as resting

spaces by passers-by. Such indigenous

appropriations of the streetscape follow along the

lines of the parklet, functioning as ‘localized

parklets’. There is a need however to accommodate

a varied range of users who belong to different age

groups and social classes within these public pockets

and technology can be used as a catalyst do this. The

smart phone is today ubiquitous and appeals to

people cutting across lines of economic, social and

educational status, and provides a sense of equity on

a technological platform.

It is essential that any design insertion which is

sensitive to the Indian context needs to withstand

challenges of vandalism, theft, and lack of

ownership by the community. The vernacular

versions of the parklets mentioned above have an

institutional management system in the form of

patronage by political parties, the local municipal

ward or community groups who use the space on a

regular basis and assert ownership through its

maintenance. These institutional mechanisms need

to be studied and adapted to create sustainable

operational models for the tech parklet.

The challenge in designing the tech parklet

would be, therefore, to meet global requirements

Localized Tech Parklets - A Concept for a New Urban Commons

73

while simultaneously responding to local challenges

and ensuring that the final outcome is socially

inclusive and accessible to all.

5 TECH PARKLET

CONSTITUENTS

The tech parklet has been devised under three main

components: the design component, the digital

component and the operational component. Each of

these will be tackled as a global prototype which

responds to local and micro conditions.

5.1 Design Component

The tech parklet will be incremental in design and

will be developed over phases. The additions at each

phase shall be made after a careful understanding of

the responses inferred from the previous phases and

the area of insertion. The basic module of the tech

parklet shall be the same as the dimensions of one

parking lot which is 3.00 m x 6.00 m.

This module is envisaged as a temporary

incremental and flexible structure which can be

modified in phases and with the potential of

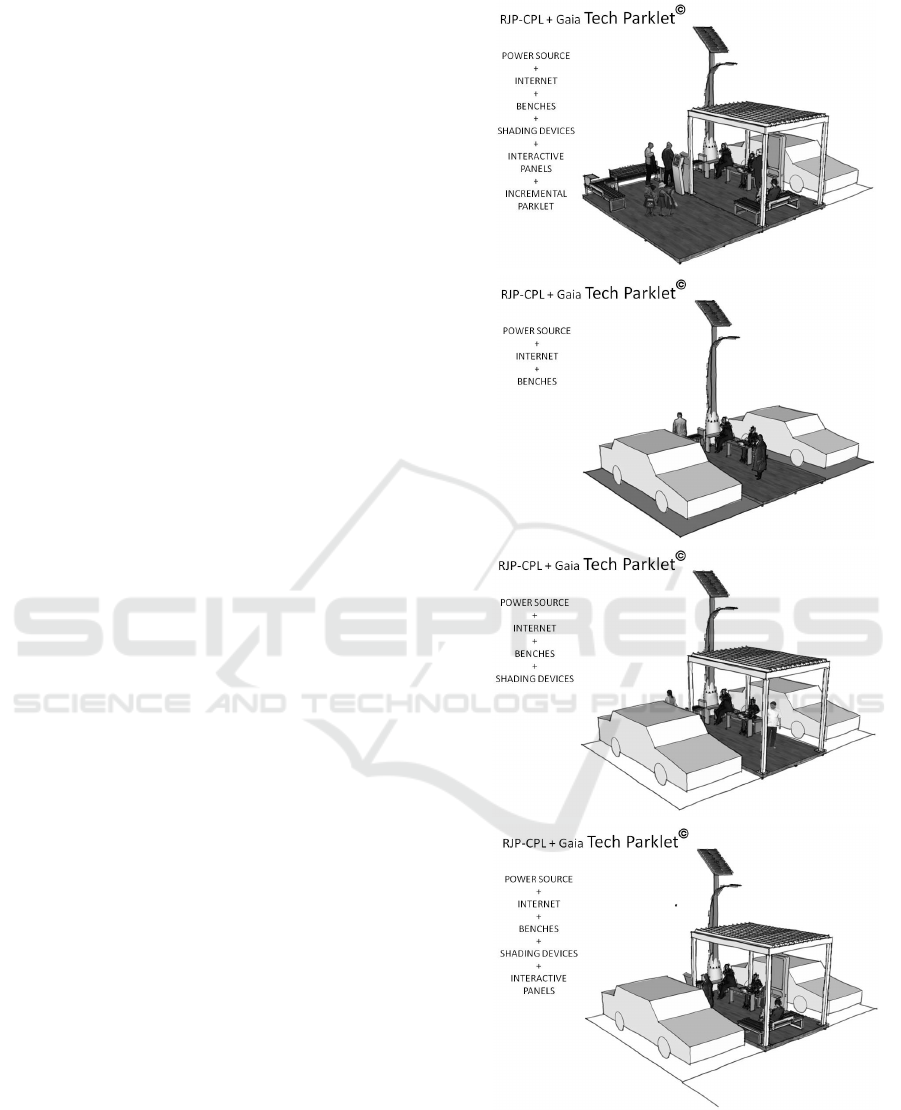

becoming a permanent public space. Figure 2 shows

the phases of the tech parklet as a conceptual design

and its incremental growth potential into a larger

public space. A major consideration of the design is

the response to the context of a public space, which

requires every component to be vandal proof, steal

proof and weather resistant. It must also be able to

create a sense of ownership with the users who

would then contribute to its maintenance and safety.

The design of the tech parklet needs to allow not just

individual digital access but also encourage

interaction and conversation between the users

which promotes educative dialogue between users.

Elements like seating and shading devices could

help create conducive and engaging spaces.

The structure is designed for flexibility and

engagement since it will be an area for information

gathering and electronic transactions, a facility for

general relaxation, as well as venue for small civic

interactions and meetings. In addition, it needs to be

protected from vandalism, theft and other perverse

activities. This is done by developing an idea of

steal-proof public furniture, which will employ

recycled materials of low intrinsic and resale value,

high durability and weather resistance. This is also

aimed at increasing the environmental sustainability

of the project.

Figure 2: RJB-CPL + Gaia Tech Parklet Design.

5.2 Technology Component

The basic module of the tech parklet will be

SMARTGREENS 2016 - 5th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

74

equipped to provide the users with primary access to

the digital sphere in the form of public Wi-Fi and

charging points. This will be a self powered system,

and would primarily utilise a solar panel as the

power source. There is a potential here to conduct

small scale experiments in other alternative methods

of clean energy generation.

Depending on the context of intervention, the

next phase could include an interactive kiosk

incorporating local applications which would range

from providing access to public utilities like bill

payment and banking portals to those that provide

health care services. Innovative components like

stationary cycles that generate electricity to charge

mobiles can be included. The tech parklet would

evolve, in response to the user patterns and

requirements, to include a wider range of

applications, information services and public

interaction systems at public spaces of larger scales.

The basic module of the tech parklet will be

equipped to provide the users with primary access to

the digital sphere in the form of public Wi-Fi and

charging points. This will be a self powered system,

and would primarily utilise a solar panel as the

power source. There is a potential here to conduct

small scale experiments in energy generation with

wind and human power as well.

Depending on the context of intervention, the

next phase could include an interactive kiosk

incorporating local applications which would range

from providing access to public utilities to those that

provide health care services. Innovative components

like stationary cycles that generate electricity to

charge mobiles can be included. The tech parklet

would evolve, in response to the user patterns and

requirements, to include a wider range of

applications, information services and public

interaction systems at public spaces of larger scales.

5.2.1 Hardware

Fundamentally, all the technology pieces are meant

for heavy duty use in rough conditions and other

harsh environmental factors with an industrial,

ruggedized design providing secure and reliable

protection. All pieces will be bolted to the floor or

housed in secure brackets. We also refrain from

specifying a processor, access speed or bandwidth or

frequency of operation, considering the speed of

technology growth and local conditions.

Digital Access: This is provided by two means

- on self owned devices via the open Wi-Fi as well as

on the interactive panels provided and housed in the

parklet. The interactive panels are simple tablets that

are developed for industrial use with panels meant for

outdoor daylight conditions that also protect the glass

from scratches and dirt. As it will be in a public

space, screen viewing angles to facilitate personal use

and information security are addressed.

Wi-Fi Router: The Wi-Fi router is a critical

component for internet access; it needs to be a high

speed device. For purposes of the Matunga

implementation, a 450 Mbps router that can operate

in dual band is used. Wi-Fi access model and

software is detailed further below.

Pedal Powered Charging: Another element

is the pedal powered Phone/Tablet Charging unit.

This is an attachment to a cycle (uni or bi) that

powers up from the pedalling motion of the bike's

rider. A dynamo, the electricity generator is powered

by the cycle wheel as a rider pedals and transfers

electricity to a charger attached to the handlebar,

which a phone or tablet plugs into. (Cnet, 2016)

(Instructables, 2016) (The Charge Cycle, 2016)

Flood Lights and Personal Light: Light is

supplied by solar powered LED floodlights as well

as individual small LED's near the interactive panels

Sensors: Motion sensors that trigger an alarm

when there is an attempt to dislodge the tablets is

another constituent of the whole offering.

Vending Machine Interface: A unit that

supports coin and bill note payments. This is then

connected to a connector that supplies power and the

two-way communication signals to a controller that

manages the duration of access and activity on the

pedal and the interactive panels or tablets.

Finally, power to the tablets and interactive

panels are solar generated or manpower generated.

5.2.2 Software

The software that manages access is meant to

regulate usage and provide a fair and democratic

means of using the parklet. Access to Wi-Fi, the

panels, the pedal powered charging unit and even

lights is controlled in a manner where certain

duration could be provided free of charge and any

duration beyond that is charged.

Both Wi-Fi access and the interactive panel is

facilitated in a manner where there is a Walled

Garden and an Open access. A walled garden or

closed ecosystem is a software system where there is

a limited set of applications, content, and media,

which is controlled and restricts access to the wider

set of applications or content. This is in contrast to an

open platform, where consumers have unrestricted

access to applications, content, and much more.

Localized Tech Parklets - A Concept for a New Urban Commons

75

Besides ensuring fair access and access to

important public services that include government

services, financial services and limited educational

or sponsored content, this is done to prevent

violation of regulatory conditions that are unclear

around open Internet usage.

5.3 Operational Component

Creating practically sustaining systems of operations

and maintenance is critical to the success of the tech

parklet. This pays attention to the capital and

operational cost of components and services, the role

of continuous suppliers, advertisers and end users,

and the integrated nature of the parklet.

The parklet needs to be treated not as a value chain

but a value circle in which the various components,

solutions and services together with the users, make a

positive contribution to resource utilization and

productivity. Advertising, sponsoring, usage charges

and transaction charges are the four means envisioned

for generating the operational costs of the parklet

All usage beyond the Walled Garden is charged.

Keeping the nature of the parklet to the unbanked or

urban poor in mind, small amounts of money or

micro payments are made directly to the vending

machine interface. This interfaces with the requisite

mechanisms controlled by the software described in

the previous section and regulates the usage

The pedal powered charging unit and the

interactive panels’ station will work for a pre-

decided duration for free. Subsequent usage will be

charged. In a manner akin to digital access, money

will be deposited into a vending machine equivalent

which triggers appropriate responses into the

systems. The solar lights could also work in a

similar manner, where costs are borne by users.

6 PROTOTYPE IN MATUNGA

The precinct of Matunga is widely recognized as an

educational hub, due to the presence of numerous

institutions, schools and colleges. The urban fabric

of this predominantly institutional area is

interspersed with residential neighbourhoods and

this overlap is what makes Matunga an interesting

area of intervention. The major stakeholders in this

area are not just the students and academicians but

also the small neighbourhood communities and

bodies like the ALM (Advanced Locality

Management) that are highly active and have a

strong sense of ownership of the public spaces.

Advance Locality Management (ALM) is a

partnership between Municipal Corporation of

Greater Mumbai (MCGM) & the citizens, for

sustainable environment friendly waste management

programme for the neighbourhoods buildings. ALM

was a scheme initiated in 1998 with 658ALMs in all

24 wards of Mumbai.

As of the writing of this paper, the authors and

their firms are involved with the citizens of the

Mogul Lane ALM in a process of re-visioning and

reinventing their neighbourhood. As part of this

process, the attempt is to integrate the component of

technology as a social tool and as a service available

to its residents. The tech parklet will be an integral

component of this attempt, where access to

technology will become a neighbourhood commons.

The tech parklet is proposed to be installed in an

area being co-created as a neighbourhood park. The

park is a citizen initiative to reclaim an existing

parking space as a community garden.

Our studies focused on the needs of the

neighbourhood, which have been identified as social

spaces, access to internet, integration of health

facilities and public provision of information and

educational services. The components of the tech

parklet have been accordingly decided as mentioned

in section 5.2 of this paper.

Another key consideration is the location of the

tech parklet, as it raises issues of ownership. The

residents of surrounding buildings avail an additional

benefit in the form of access to Wi-fi from the

comforts of their home. This vested interest can be

harnessed to motivate the residents to keep watch on

the tech parklet and prevent it from being vandalized.

The funding for the hardware component of the

prototype is being sourced through Corporate Social

Responsibility initiatives of businesses located in the

neighbourhood. The software and network

provisions are being sourced though network

providers in return for advertising rights. In this

manner, the project creates a model for a Public-

Private-Community engagement at a localised and

neighbourhood scale.

As of the writing of this paper, this project is at

the stage of community co-design where the

residents along with RJB-CPL and Gaia are ideating

the design and facilities of the tech parklet.

The tech parklet, still at an early phase of

development, does not have any specific scientific

studies yet. The open ended and co-productive

nature of the project also implies that we do not start

with a fixed idea of design or technical

specifications. While we have a basic programme

for the parklet as a starting point, the eventual result

will be a product which evolves with our process

SMARTGREENS 2016 - 5th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

76

and inputs from the stakeholders.

Since this is a very exciting new concept for urban

space, we also have a number of private players keen

on sponsoring the project or trying out pilots of their

own products in this space. However, this also brings

up questions concerning the level of private interests

that can be accommodated in the creation of a public

space, and these issues are to be debated at

multilateral meetings with the stakeholders.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The tech parklet has broadly two interconnected

aspirations- one, to create a lasting urban commons

and the other is to create this commons as a

contemporary urban space where the physical and

digital realms intersect.

Common spaces are not designated. They are

claimed. In cities, common spaces can be the spaces

of intersection and interstice. This sort of commons

arises from experiments and trials to rethink our urban

spaces. Acting in interstitial spaces re-subjectivates

the space and the actors and they remain so only as

long as they are relentlessly pursuing the commons. A

commons therefore must be maintained through

continuous community action and continuous re-

invention by becoming a ground for negotiation rather

than affirmation. (Balasubramanian, 2014) The tech

parklet therefore is an attempt to go beyond the

temporality of the Park(ing) Day, and to create lasting

public spaces. Therefore the project tackles the task at

the levels of urban design, technology and operational

sustainability with a participatory and process

oriented approach.

The tech parklet also questions the concept of

public and private goods, and expands the definition

of the public realm to include the digital space. It

engages the debates of accessibility and inclusivity of

public services while at the same time tackling issues

of privacy and the potential of misuse of technology.

The project also tackles the institutional mechanisms

of setting up tech parklets and its operational

sustainability, while at the same time engaging the

agency of citizens and designers in the production of

public space. Tech parklets are a new venture into

rethinking and linking our physical and digital

identities in increasingly networked urbanities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank our colleagues at RJB CPL and Gaia

Smart Cities.

Ratan J Batliboi – Consultants Private Limited,

Mumbai, is an architecture and urban design studio

engaged in urban research, urban planning and urban

design. The firm specializes in public space design

and rethinking urban public action through bottom

up community based socio-spatial innovation.

Gaia Smart Cities Solutions Private Limited is a

novel technology company converging areas of

telecom, software and sensors paving the way for the

next wave of the Internet - the Internet of Things and

Smart Cities.

REFERENCES

Anon., 2016. [Online] Available at: http://www.thecharge

cycle.com/element.html.

Anon., 2016. [Online] Available at: http://www.instructab

les.com/id/Pedal-Powered-Battery-Charger/

Anon., 2016. Advanced Locality Management, MCGM.

[Online] Available at: http://www.mcgm.gov.in/irj/por

tal/anonymous/qlvarprg.

Anon., 2016. Cnet News. [Online]

Available at: http://www.cnet.com/news/nokia-unveils

-bicycle-powered-phone-charger/

Balasubramanian, R., 2014. For the Common, by the

Common: Reclaiming the Urban Spatial Commons in

Bangalore, Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

De Angelis, M., 2005. The New Commons in Practice:

Strategy, Process and Alternatives, s.l.: Development

48 (2).

De Moor, T., 2011. From common pastures to global

commons: a historical perspective on interdisciplinary

approaches to commons. Natures Sciences Societes,

pp. 422-431.

DoT, D. o. T., 2012. National Telecom Policy, New Delhi:

Ministry of Communications & IT, Government of

India.

Harvey, D., 2013. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City

to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

McKinsey, 2016. Internet matters. [Online]

Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_

tech_telecoms_internet/internet_matters.

Petrescu, D., 2008. How to Reclaim the Common?. In:

Operation: City The Neoliberal Frontline: Urban

Struggles in Post-Socialist Societies, Zagreb. Zagreb:

s.n., pp. 25-26.

Policansky, D., 1999. Revisiting the Commons: Local

Lessons, Global Challenges. Science.

RebarGroup, 2016. [Online]

Available at: http://rebargroup.org/parking-day/

Unnikrishnan, H. H. N., 2013. Privatization of commons:

Impacts on traditional users of provisioning and

cultural ecosystem services, Bangalore: s.n.

Localized Tech Parklets - A Concept for a New Urban Commons

77