The Potential of Smartwatches for Emotional Self-regulation of

People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Juan C. Torrado, Germán Montoro and Javier Gomez

Department of Computer Engineering, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Keywords: Smartwatches, Self-regulation, Autism, Assistive Technologies, Affective Computing, Pervasive Computing.

Abstract: This paper focuses on the potential of smartwatchers as interventors in the process of emotional self-regulation

on individuals with ASD. Parting from a model of assistance in their self-regulation tasks, we review the main

advantages of smartwatches in terms of sensors and pervasive interaction potential. We argue the suitability

of smartwatches for this kind of assistance, including studies that had used them for related purposes, and the

relation of this idea with the affective computing area. Finally, we propose a technological approach for

emotional self-regulation assistance that uses smartwatches and applies to the mentioned intervention model.

1 INTRODUCTION

People with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)

usually show symptoms that affect their behavior.

Experts attribute this to their deficit in the executive

function, which is defined as the ability to control

actions (Baron-Cohen and Chaparro, 2010).

Although executive dysfunction is better known

because of its effects on planning and organization

skills, it also affects behavior and some other abilities,

such as impulse control, inhibition of inappropriate

responses and flexibility of thought and action

(Ferrando et al., 2002).

Considering the daily life of a person with ASD,

the aforementioned deficit in executive function may

lead to the following practical difficulties:

Difficulty in organization and sequencing of steps

to complete a certain task.

Difficulty to identify the starting and ending

points of a certain task.

Difficulty in behavioural and emotional

regulation.

These are high functional limitations and they are

closely related to behavioral disturbances. Proper and

adapted support and help are essential to achieve

major improvement, even more when the assistance

is provided by means of self-regulation strategies.

This kind of support reduces dependency on

caretakers and makes feasible to adapt these strategies

to the users’ contexts (Laurent and Rubin, 2004).

In general, the main goal of these supportting

strategies is to increase users’ self-determination.

Self-determined behavior is composed of four

necessary features: autonomy, self-regulation,

empowerment and self-fulfillment (Nota and Ferrari,

2007). Specifically, self-regulation involves several

aspects of self-determined behaviors: choosing and

decision-taking, problem solving, goal setting, skill

acquisition and internal control.

Regarding emotional and behavioral self-

regulation, Pottie and Ingram (Pottie and Ingram,

2008) presented a model set of tasks that new

strategies or developments must help in:

1. Define a scale of emotional intensity.

2. Adjust the emotional reaction to the proper

intensity

3. Identify situations that provoke varied emotional

intensities and adapt the emotional reaction to

them.

4. Develop strategies of emotional control.

5. Identify stressful situations.

6. Create ways to avoid non-desired situations.

7. Manage the stress of non-desired situations.

8. Manage anger episodes.

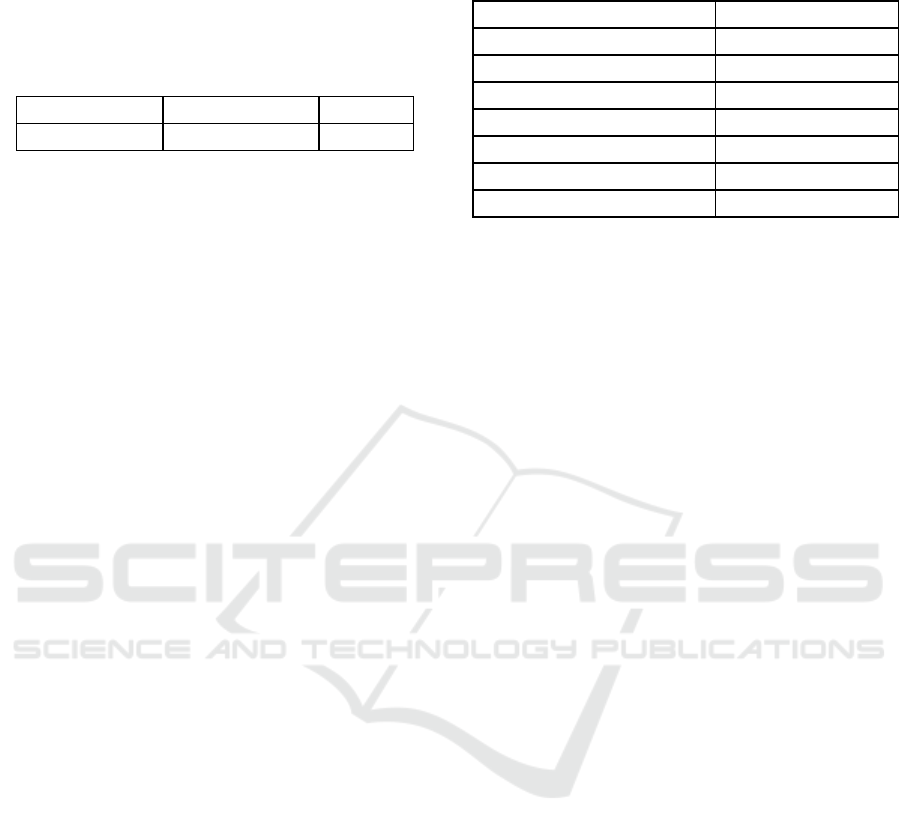

Besides, these tasks can be classified into three

groups or stages: preprocessing, identification and

management. Table 1 summarizes the mapping

between stages and tasks.

Therefore, this supporting tasks can be considered

as requirements for technology to aid people with

444

Torrado, J., Montoro, G. and Gomez, J.

The Potential of Smartwatches for Emotional Self-regulation of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

DOI: 10.5220/0005818104440449

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2016) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 444-449

ISBN: 978-989-758-170-0

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

ASD in their emotional self-regulation. In further

sections, we propose a new approach to enhance the

process of emotional self-regulation by means of

emerging technologies.

Table 1: Self-Regulation stages and associated tasks.

Preprocessing Identification Tasks

1 3, 5 2,4,6,7,8

2 ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGIES

FOR EMOTIONAL FUNCTION

The application of technology to support people with

cognitive disabilities is not a new idea. The concept

of assistive technology (World Health Organization,

2007) includes the whole set of functional diversity:

physical prostheses, glasses, wheelchairs, etc.

However, having a specific type of assistive

technology that involves cognitive aspects of users

became necessary. Thus, assistive technology for

cognition (ATC) was born (O’Neill and Gillespie,

2014). Gillespie et al., (2012) reviewed and mapped

ATC products to the International Classification of

Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World

Health Organization, 2007). In other words, they

analysed thoroughly the relationship between the

cognitive functions and necessities of people with

cognitive disabilities and the assistive products made

for them. For this mapping they also classified ATC

function into alerting, distracting, micro-prompting,

navigating, reminding, storing and displaying, and

mixed function. Through a systematic review of ATC

studies they found a strong relationship between their

classification of ATC function and the ICF cognitive

functions (see Table 2). Thus, attention problems are

usually treated by alerting technology, distracting

technology brings emotion regulation, navigating

technology covers experience-of-self issues, micro-

prompting is for organization and planning, storing

and displaying is used for memory problems and

reminders for time management.

From this study we can conclude that distracting

technologies have been used to propose solutions to

emotional and behavioural issues of users with

cognitive impairment. ICF defines emotional

functions as specific mental functions related to the

feeling and affective components of the processes of

the mind. “Distracting technologies” is a wide term,

which goes from devices that provide with stimuli to

prevent from hallucinations (Johnston and Gallagher,

2002) to biofeedback systems (Sharma et al., 2014).

Table 2: Mapping of ICF cognitive functions to ATC

functions (Gillespie et al., 2012).

ICF cognitive function ATC function

Attention Alerting

Calculation Mixed

Emotion Distracting

Experience of self Navigating

Organization and planning Micro-prompting

Time management Reminders

Memory Storing and displaying

This reasoning serves us to define the type of

function that a technological system oriented to assist

a user with ASD in his emotion self-regulation should

satisfy.

3 SMARTWATCHES AS

EMERGING TECHNOLOGY

3.1 Emerging Technologies

The main problem when it comes to speak about

emerging technologies is that is a vague, fleeting

term. Due to the accelerated course of technology

advancement, emerging technologies today are

completely different from emerging technologies few

years ago.

However, the term itself has been used since the

appearance of smartphones and IoT (Internet of

Things) related technologies (Bijker et al., 2012).

Evidently, nowadays we cannot speak about

smartphones as emerging technologies, but as

widespread technologies, and this change took only a

few years. Once smartphones became widespread

technologies, used and accepted by millions of users

(File, 2013), researchers started to think about their

application to science as a means instead of an end,

especially on social sciences (Dufau et al., 2011).

Thus, the number of research studies that used

smartphones as the main vehicle for experimentation

augmented considerably.

ATC studies also took advantage of this

phenomenon, and many researchers studied the use of

smartphones with users with cognitive disabilities in

their daily life. Lancioni et al., (2012), through the

observation of the results from several experiments

that used widespread technologies on cognitive

impaired users, argued the importance of studying the

adaptation of new technologies before they became

popular, parallelizing the design for standard users

and its adaptation to users with diverse functionality.

The Potential of Smartwatches for Emotional Self-regulation of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

445

The underlying motivation of this paper is to

encourage the adaptation of emerging technologies,

whilst they continue being so. This way, relevant

emerging technologies will reach an accepted and

widespread usage state at the same time for cognitive

impaired people and for standard population.

So then, which are the most leading emerging

technologies nowadays? Do they project an

optimistic future regarding to market and users? Is it

feasible to plan their adaptation to users with special

needs? Will be the next technological generation,

after smartphones and tablets, as popular as them?

Serious predictions are very difficult to engage

since they depend on numerous factors, but many of

them are oriented towards an emerging device that

will be treated in this article: wearable technologies,

specifically smartwatches (Kerber et al., 2014)

(Rawassizadeh et al., 2014).

3.2 Smartwatches

Smartwatches are wearable, wrist-held devices that

are starting to offer similar functionality to

smartphones, adapting its use and interaction to a new

paradigm, and considering its limitations due to their

lower resources (Witt, 2014). The most remarkable

feature of smartwatches is their wide sensing set:

accelerometer, heart rate monitor, GPS, light sensor,

Wi-Fi, etc. These devices also offer varied interaction

possibilities: tactile screen, vibration feedback or

voice recognition. They can be considered the first

wearable technology with true computing power and

versatility.

That is why these devices have already raised

attention between researchers of cognitive disabilities

and social scientists. Kearns et al., (2013) developed

their own smartwatch, integrated in a smarthome,

which served as support for people with cognitive

impairment in their daily life activities. This system

also helps them planning and reminding tasks.

Researchers concluded that the reminder was the

more effective aspect of their system (reminding

medications and punctual tasks during a day). This

study serves to understand that this platform is useful

for these individuals, but regarding our aim, it is not

an example of the ATC function that we are looking

for (distracting technology for emotional self-

regulation instead of micro-prompting and reminders

for planning and memory issues) and it has been

implemented in their own smartwatches, whereas we

look for a widespread use, so commercial or industrial

prototypes are preferable.

Similar conclusions can be extracted from the

study of Sharma and Gedeon (2012), who used

smartwatches connected to smartphones as an aid to

the treatment of people with Parkinson syndrome.

This system offered the advantage of using a

commercial device (Pebble) that made it feasible to

reproduce the experiment in larger groups and

different conditions.

Smartwatches, understood as portable sets of

sensors, were used by Bieber (Bieber et al., 2012) to

propose applications for ambient assistant living

environments. Their study focuses on the non-

intrusive aspect of smartwatches, and their capability

of being centers of permanent sensing and

notification in your own wrist.

Those studies used smartwatches for assistive

technologies related purposes. However, there are no

previous experiences of their use for emotional self-

regulation, where they have a great potential to cover

the necessities commented at earlier sections, as we

will discuss in the proposal.

4 AFFECTIVE COMPUTING

Affective computing refers to any computing

application or system that “relates to, arises from, or

influences emotions”, as stated Rosalind Picard in the

paper that coined the term (Picard, 1997). Moreover,

some researchers focus on emotions as a new way of

interaction with technology (Picard, 1999). However,

the main challenge of affective computing is the

detection and interpretation of human emotions. In

psychology, the Theory of Emotions displays them

regarding to two axis: arousal and valence; stress is

an emotion of high arousal and low valence, whereas

joy comprises high arousal and high valence. An

example of both low arousal and valence is sadness,

and one of low arousal and high valence is relax

(Hernandez and Li, 2014).

5 PROPOSAL

Analyzing the necessity of applying technology to the

emotional self-regulation of individuals with ASD

has led us to review different applications in this area.

However, most of them are based on technology

specifically developed for each case, or require

certain technology knowledge to be used.

Smartwatches can be a natural approach to

technology, and a good option to offer technological

support in an attractive and normalized way. The

intention is that the assistance is given though the

smartwatch, not needing external, unknown or stran-

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

446

Figure 1: Application of smartwatches in the emotional self-regulation process of an individual with ASD.

ge devices. Situations that require emotional self-

regulation arise spontaneously: getting nervous when

walking through an unknown environment, receiving

stimuli related to user’s phobia, stressful situations

derived from social interaction, etc. Whatever the

situation, the smartwatch can be always directly

available for the user, in their wrist. Moreover,

smartwatches have enough sensing power to detect

these situations, assist and register them.

Our proposal is a technological approach of the

model explained by Pottie and Ingram (2008) (see

Table 3), using smartwatches as well as computing

affective techniques for detection and analysis and

ATC procedures for interaction and pervasive

assistance. Concretely, the smartwatch system (an

application or service) would be able to perform the

following tasks (see Figure 1):

Detect stressful situations: the inward state of the

individual with ASD gives signals that imply

stress or anxiety; the smartwatch is able to detect

them through sensing the heart rate or arm

movement, involving affective computing

analysis in the process.

Create ways to avoid non-desired situations: this

can be achieved by text, image and audio

prompting in the screen of the smartwatch,

providing instructions that tell the user what to do

to avoid these situations.

Manage the stress of non-desired situations: not

always it is possible or recommendable to avoid

certain situations that may cause stress to these

individuals. In these cases, smartwatches can act

as distractors or prompters, showing media that

makes the user pay less attention to the stressful

situation and getting feedback about how well it is

the situation going.

Define a scale of emotional intensity: the above

mentioned prompting can be made using language

that includes vocabulary and image-based media

with emotional education purposes, asking the

user what is his emotional state within a scale or

giving names to different emotions perceived by

the user in certain situations.

Table 3: Self-Regulation stages and associated tasks.

Self-regulation model System function

Identify problematic

situations

Smartwatch sensors +

Affective Computing analysis

Define a scale of emotional

intensity

Affective Computing analysis

Manage stressful situations

Smartwatch distractors and

prompting

Avoid non-desired situations Smartwatch prompting

Adjust emotional reaction to

specific situations

Smartwatch timers and

prompting

Manage anger episodes

Smartwatch timers and

prompting

For example, this stressful situation can be seeing

a big dog. If the user is afraid of them, the smartwatch

will notice it through his heart rate or arm movement

when repelling the dog. The smartwatch will try to

catch his attention through vibration and sound, and

The Potential of Smartwatches for Emotional Self-regulation of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

447

then the app will tell the user what to do (go to another

place, ask a reliable person for going to another place,

etc.). After that, a distractor or mini-game in the

screen of the smartwatch, that will help the user to

recover the initial, calm emotional state. In case it is

recommendable to teach the user to manage a

situation with the presence with big dogs (for

example, if he lives in a zone with several of them),

the prompting would help him to understand the lack

of danger in these situations, along with more

distractions in these situations.

Currently we are developing these ideas by means

of two smartwatches based on Android Wear OS,

targeting a full-functional version and some user

experiments that cover several situations that might

provoke stress or uneasiness, so we can tell whether

smartwatches can be applied ubiquitously to this

learning process, as the discussed theory in this paper

proposes.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Smartwatches are devices with great potential in the

fields of Assistive Technologies and Affective

Computing. They contain a wide –and growing- set

of sensors, constantly in touch with the inward and

outward state of the user. This implicit interaction

produces data that can be used to assist the user in

terms of new software possibilities. These capabilities

are particularly helpful in the assistance of emotional

self-regulation, which is a problematic issue for

people with ASD. The most effective techniques to

achieve an acceptable skill of emotional self-

regulation in these individuals are stated by several

authors involving assistive technology and pedagogy,

and they include timers, distractors and prompting.

These exercises and methods are feasible to be

implemented in a smartwatch, as well as the affect

detection, necessary to trigger the assistance.

Affective computing analysis can be integrated in the

sensing process of the smartwatch, and interactive

assistance can be modelled and performed through

the device’s screen. Taking into account these ideas,

we map the needs of these individuals in terms of self-

regulation to the technological possibilities of these

devices, proposing a system that would be able to

help ASD to improve their emotional self-

management by means of a well-known, widespread

device, at the same time it is being popularized in

society and normalized its use between mainstream

users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been partially funded by the projects

“e-Training y e-Coaching para la integración socio—

laboral” (TIN2013--44586--R) and “eMadrid-CM:

Investigación y Desarrollo de Tecnologías

Educativas en la Comunidad de Madrid”

(S2013/ICE-2715). It has been also funded by

Fundación Orange during the early stages of the

project “Tic-Tac-TEA: Sistema de asistencia para la

autorregulación emocional en momentos de crisis

para personas con TEA mediante smartwatches”.

REFERENCES

Baron-Cohen, S., & Chaparro, S. (2010). Autismo y

síndrome de Asperger.

Bieber, G., Dwlrq, Y., Iru, P., Hqylurqphqw, Z., Sulydwh,

D. Q. G., Ri, J., Wkh, W. R. (2012). Ambient

Interaction by Smart Watches. Proceedings of the 5th

International Conference on PErvasive Technologies

Related to Assistive Environments, PETRA ’12.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2413097.2413147.

Bijker, W., Hughes, T., Pinch, T., & Douglas, D. (2012).

The social construction of technological systems: New

directions in the sociology and history of technology.

Dufau, S., Duñabeitia, J., & Moret-Tatay, C. (2011). Smart

phone, smart science: how the use of smartphones can

revolutionize research in cognitive science. PloS One.

Ferrando, M., Martos, J., Llorente, M., & Freire, S. (2002).

Espectro autista. Estudio epidemiológico y análisis de

posibles subgrupos. Revista de Neurología.

File, T. (2013). Computer and internet use in the United

States. Current Population Survey Reports, P20-568.

US….

Gillespie, A., Best, C., & O’Neill, B. (2012). Cognitive

Function and Assistive Technology for Cognition: A

Systematic Review. Journal of the International

Neuropsychological Society, 18(01), 1–19.

http://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617711001548.

Hernandez, J., & Li, Y. (2014). BioGlass: Physiological

parameter estimation using a head-mounted wearable

device. … (Mobihealth), 2014 EAI….

Johnston, O., & Gallagher, A. (2002). The Efficacy of

Using a Personal Stereo to Treat Auditory

Hallucinations Preliminary Findings. Behavior ….

Kearns, W., Jasie-, J. M., Fozard, J. L., Webster, P., Scott,

S., Craighead, J., … Mccarthy, J. (n.d.). Temporo-

spacial prompting for persons with cognitive

impairment using smart wrist-worn interface.

Kerber, F., Kruger, A., & Lochtefeld, M. (2014).

Investigating the Effectiveness of Peephole Interaction

for Smartwatches in a Map Navigation Task.

Proceeding MobileHCI ’14 Proceedings of the 16th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction with Mobile Devices & Services, 291–294.

HEALTHINF 2016 - 9th International Conference on Health Informatics

448

Lancioni, G., Sigafoos, J., O’Reilly, M., & Singh, N.

(2012). Assistive technology: Interventions for

individuals with severe/profound and multiple

disabilities.

Laurent, A., & Rubin, E. (2004). Challenges in Emotional

Regulation in Asperger Syndrome and High

Functioning Autism. Topics in Language Disorders.

Nota, L., & Ferrari, L. (2007). Selfdetermination, social

abilities and the quality of life of people with

intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual.

O’Neill, B., & Gillespie, A. (2014). Assistive Technology

for Cognition. Handbook for Clinicians and

Developers.

Organization, W. H. (2007). International Classification of

Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth

Version: ICF-CY.

Picard, R. (1997). Affective computing.

Picard, R. (1999). Affective Computing for HCI. HCI (1).

Pottie, C., & Ingram, K. (2008). Daily stress, coping, and

well-being in parents of children with autism: a

multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family

Psychology.

Rawassizadeh, R., Price, B. a., & Petre, M. (2014).

Wearables. Communications of the ACM, 58(1), 45–47.

http://doi.org/10.1145/2629633.

Sharma, N., & Gedeon, T. (2012). Objective measures,

sensors and computational techniques for stress

recognition and classification: A survey. Computer

Methods and Programs in Biomedicine.

Sharma, V., Mankodiya, K., De La Torre, F., Zhang, A.,

Ryan, N., Ton, T. G. N., Jain, S. (2014). SPARK:

Personalized Parkinson Disease Interventions through

Synergy between a Smartphone and a Smartwatch.

Design, User Experience, and Usability. User

Experience Design for Everyday Life Applications and

Services, 103–114. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-

07635-5-11.

Witt, S. (2014). Wearable Computing: Smart Watches. Fun,

Secure, Embedded.

The Potential of Smartwatches for Emotional Self-regulation of People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

449