The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin:

Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

Yue Yu and Yicheng Wu

Centre for the Study of Language and Cognition, Zhejiang University, 148 Tian Mu Shan Road, Hangzhou, China

Keywords: Mandarin, Elliptical Predicate Construction, Pro-form, Semantic Underspecification, Pragmatic Enrichment,

Context.

Abstract: This paper attempts to present a unitary account of a range of elliptical predicate constructions in Mandarin,

such as Null Object Constructions, English-like VP ellipsis constructions, and gapping constructions. It is

argued that (i) from an interpretative perspective, the ellipsis site in the above-mentioned elliptical

constructions can be uniformly analyzed as a pro-form with underspecified content; (ii) the interpretation of

both syntactically and semantically underspecified constructions as such is crucially dependent on context.

Within the framework of Dynamic Syntax (Kempson et al. 2001; Cann et al. 2005), the null object in Null

Object Constructions, the null verb phrase in English-like VP ellipsis constructions and the null verb in

gapping constructions are consistently analyzed as projecting a metavariable whose semantic value is

pragmatically enriched from context by means of “substitution”/“re-use”. It is thus shown that syntactic and

pragmatic processes interact to determine the underspecified content of elliptical predicate constructions in

Mandarin. The dynamic analysis proposed provides a formal and unitary characterization of a variety of

elliptical constructions without any stipulations.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper we attempt to provide a unitary account

for a range of elliptical predicate constructions in

Mandarin, such as Null Object Construction,

English-like VP ellipsis, and Mandarin gapping

construction, as exemplified by (1)-(3) below,

respectively.

(1) 张三喜欢英语,李四也喜欢。

Zhangsan xihuan yingyu. Lisi ye xihuan ([e]).

Zhangsan like English Lisi also like

‘Zhangsan likes English. Lisi also likes (it).’

(2) [张三在爬树。]

[Zhangsan zai pashu.]

[Zhangsan ASP climb tree]

[‘Zhangsan is climbing a tree.’]

李四:我也敢。

Lisi: wo ye gan ([e]).

I also dare

‘So dare I.’

(3) 张三吃了三个苹果,李四四个橘子。

Zhangsan chi-le san-ge pingguo, Lisi___si-ge

juzi.

Zhangsan eat-ASP three-CL apple Lisi__four-CL

orange

‘Zhangsan ate three apples, and Lisi__four

oranges.’

In (1), the object in the target clause of the Null

Object Construction is apparently missing with the

main verb repeated. English-like VP ellipsis

presented in (2) is licensed by modals such as 会

(hui) ‘will’, 能 (neng) ‘can’, and 敢 (gan) ‘dare’.

The main verb in the gapping construction (3) is left

unexpressed in the subsequent clause. The fact that

syntactically underspecified constructions as such

can be perfectly understood indicates that the ellipsis

site is crucially dependent on context for its

interpretation. Obviously, the constituents at issue

can only be left out if there is a straightforward way

for the hearer to recover their meanings from the

context, be it linguistically (as in (1) and (3)) or non-

linguistically (as in (2)).

The context-dependent nature of interpreting

elliptical constructions suggests that the

underspecified content associated with the

unexpressed syntactic constituents requires to be

pragmatically enriched. This points to a hypothesis

that the elliptical site projects a meta-variable which

takes its value from context, either from a linguistic

Yu, Y. and Wu, Y.

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment.

DOI: 10.5220/0005830003230334

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2016) - Volume 1, pages 323-334

ISBN: 978-989-758-172-4

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

323

antecedent or the discourse context. The central

thesis of this paper is that an adequate account of

elliptical constructions should be couched in terms

of semantic underspecification and pragmatic

enrichment.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2

presents a critical review of previous analyses of the

elliptical constructions illustrated above. Section 3

introduces the theoretical framework to be

employed, namely, Dynamic Syntax (Kempson et al.

2001; Cann et al. 2005). Section 4 presents a

dynamic account of the constructions exemplified by

(1)-(3). A summary is made in section 5.

2 PREVIOUS ANALYSES

As for Null Object Construction as (1), there are

mainly two lines of analyses. One argues that there

exists V-Stranding VP ellipsis (alternatively known

as VP ellipsis in disguise) in Mandarin which can be

differentiated from Null Object Construction (see

Huang 1991a; Li 2002; Ai 2008 inter alia), whereas

the other maintains that V-Standing VP ellipsis in

Mandarin is actually nothing more than Null Object

Construction (e.g. Xu 2003). V-Stranding VP

ellipsis is derived through the deletion of VP after

the main verb goes through V-to-v movement, with

the main verb being stranded. The NP gap is no

longer a null object, but an elided VP. Later, the

moved verb has to be reconstructed back through

Logical Form reconstruction (LF-reconstruction) to

get a full semantic interpretation for the target

clause.

Li (2002) points out that V-Stranding VP ellipsis

in Mandarin should be approached from the

perspective of verb types, which can be

differentiated into stative verbs, resultative verbs and

action verbs. Moreover, he mentions that in any

given V-Stranding VP ellipsis contexts (e.g. under

syntactic control), the aforementioned constructions

show strict and sloppy readings

1

, just like English-

like VP ellipsis constructions. However, Ai (2008)

1

When the elliptical site includes a pronoun, the interpretation of the

elliptical clause show strict and sloppy effect, as in the following

example:

张三喜欢他的老师。

Zhangsan xihuan ta-de laoshi.

Zhangsan like his teacher

‘Zhangsan likes his teacher.’

李四也喜欢。

Lisi ye xihuan__.

Lisi also like

Strict reading: ‘Lisi also likes Zhangsan’s teacher.’

Sloppy reading: ‘Lisi also likes Lisi’s teacher.’

argues against Li’s statements, holding that Li’s

approach is of no significant results, and to have a

linguistic antecedent (here to be under syntactic

control) is not a guarantee that the target is an

instance of VP ellipsis, because the target can also

be an instance of deep anaphora in the sense of

Hankamer and Sag (1976) (like do it/that anaphora).

Moreover, he proposes that the traditional

diagnostics for VP ellipsis such as the strict and

sloppy ambiguity are not sufficient as do it/that

anaphora also shows such traits. He believes that

there do exist V-Stranding VP ellipsis constructions

in Mandarin, but Li has looked at the wrong place

for relevant arguments.

According to Ai (2008), examples like (1) are

instances of V-Stranding VP ellipsis rather than Null

Object Constructions, on the ground that if the

construction at issue can tolerate pragmatic control

(without linguistic antecedent), it might be an

instance of Null Object Construction, while if it

cannot, it must be an instance of V-Stranding VP

ellipsis, an instance of VP ellipsis, which is typically

known to resist pragmatic control. Having

differentiated strong pragmatic control from weak

pragmatic control in terms of the availability of a

linguistic topic (if there is no linguistic topic, it is an

instance of strong pragmatic control; if there is one,

it is an instance of weak pragmatic control), he

further argues that genuine V-Stranding VP ellipsis

in Mandarin can be found only in places of strong

pragmatic control when the null object happens to be

[-animate]. As pointed out by him, [-animate] null

objects resist strong pragmatic control as in (4):

(4) [Zhangsan drives home in his new BMW].

Lisi [to his wife]:

# 我一点儿都不喜欢。

# Wo yi-dian-er dou bu xihuan[

NP

Ø].

I one-bit all not like

‘I do not like (it) at all.’

(it=Zhangsan’s new BMW)

(Ai 2008: 108, (37))

Though appealing, this account does not seem to

be on the right track, both theoretically and

empirically. Theoretically, the diagnostic of

pragmatic control for VP ellipsis constructions does

not hold in Mandarin, different from that in

English

2

. As a piece of evidence, example (2) can

well tolerate pragmatic control. Empirically, the [±]

animate property of the null object does not make a

2

As mentioned in Hankmaer and Sag(1976), VP ellipsis constructions

in English resist pragmatic control, as in the example below:

[Hankamer attempts to stuff a 9-inch ball through a 6-inch hoop]

Sag: #It’s not clear that you will be able to.

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

324

difference in the acceptability of relevant utterances

according to my informants, that is, the acceptability

of (4) and (5) is equal.

(5)[Zhangsan walks home in his new adopted

husky].

Lisi [to his wife]:

我一点儿都不喜欢。

Wo yi-dian-er dou bu xihuan[

NP

Ø].

I one-bit all not like

‘I do not like (it) at all.’

(it=Zhangsan’s new adopted husky)

(Ai, 2008: 109, (38))

Moreover, according to Ai’s analysis, we would

reach the conclusion that the elliptical site in (4) is

derived through VP deletion after the main verb 喜

欢 (xihuan) ‘like’ goes through V-to-v movement,

whereas the elliptical site in (5) can be either a

deictic pro or a referential null epithet, for instance,

the covert counterpart of 那玩意儿 (na wanyi-er)

‘that play thing’. The same structure is imposed with

two distinct derivation and interpretation processes,

which are far from satisfactory. Apparently, a more

unified and consistent analysis remains to be

achieved. In this paper, we follow Xu (2003) and

maintain that examples like (1) are nothing more

than Null Object Constructions.

As for the derivation and interpretation of

English-like VP ellipsis as (2) in Mandarin, there are

mainly two approaches proposed in the literature:

Phonetic Form deletion (PF deletion) (see Huang

1991b, 1997; Ai 2008 inter alia) and Logical Form

reconstruction (see, e.g. Li 2005). While the former

assumes a full-fledged syntactic structure for the VP

gap prior to Spell-Out, the latter assumes that the

gap is a base-generated pro-form of VP and its

content, including its syntactic structure, can be fully

reconstructed at the Logical Form. Following Huang

(1991b, 1997), the derivation of English-like VP

ellipsis in Mandarin can be represented as:

Subject

i

(Neg) modal/auxiliary [

vP

…[

VP

-t

i

…]]

(Ai 2008)

After the subject is extracted out of the ellipsis

site, the remaining element, namely, vP, is deleted,

which can be illustrated by (6) below.

(6) [

IP

张三

i

敢 [

vP

t

i

[

VP

爬树]]], [

IP

我

j

也敢[

vP

t

i

[

VP

爬树]]].

[

IP

Zhangsan

i

gan [

vP

t

i

[

VP

pa shu]]],[

IP

Wo

j

ye

gan [

vP

t

i

[

VP

pa shu]]].

[

IP

Zhangsan

i

dare [

vP

t

i

[

VP

climb tree]]], [

IP

I

j

also

dare [

vP

t

i

[

VP

climb tree]]].

‘Zhangsan dare to climb a tree, so dare I.’

The other approach in the literature is Logical

Form reconstruction (LF-copy). The target VP is

considered to be base-generated as a pro-form of VP

that has no structure after Spell-Out. For the

interpretation of the target elliptical clause, the

relevant VP in the antecedent clause has to be copied

into the gap. Li (2005) holds that the existence and

the meaning of the base-generated pro-form are

determined by the selection property of a head. Only

the constituents selected by the head can exist as

empty elements, for instance, modals select VP:

(7) 小明能讲英语,小红也能。

Xiao Ming neng jiang yingyu, Xiao Hong ye

neng[e].

Xiao Ming can speak English Xiao Hong also

can.

‘Xiao Ming can speak English, so can Xiao

Hong.’

The head 能 (neng) ‘can’ selects a VP, therefore,

in (7) the VP 讲英语 (jiangyingyu) ‘speak English’

is selected by the head 能 (neng) ‘can’ and can exist

as an empty element. Though appealing at first sight,

this approach can only deal with limited VP ellipsis

materials. The gapping example (3) is left

unexplained, as what is not overtly expressed is the

head.

(3) illustrates the structure of gapping, in which

the main verb is null in the subsequent clause.

Gapping in English, as shown in (8), is traditionally

analyzed as (VP-) ellipsis with VP deletion after the

target object being moved out of the relevant VP at

the Phonetic Form, or across the board V/VP

movement (see Johnson 1994, 2004, 2006, 2009).

(8) John likes apples and Mary __oranges. (Ai

2014: 125, (1))

Tang (2001) assumes that examples like (8) are

simply empty-verb sentences rather than instances of

gapping. Recently, Ai (2014) has proposed a

different analysis of English-like gapping

constructions in Mandarin. He takes issue with both

Johnson’s and Tang’s analyses. With respect to

Johnson’s across-the-board-movement analysis, Ai

(2014: 128) claims that it fails to account for

English-like gapping in Mandarin, because gapping

in Mandarin is not restricted to coordinate structures,

nor does it seem to obey typical island constraints.

Regarding Tang (2001)’s assumption, Ai argues

instead that empty verb sentences have a rather

limited distribution in Mandarin, and the

“reconstructed” verbs in empty-verb sentences do

not have to be identical, a case being different from

gapping, an instance of ellipsis, for which “identity”

is always the licensing condition. Adopting a

methodology that separates the target clause from

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

325

the antecedent clause, Ai (2014: 131) contends that

English-like gapping in Mandarin “is nothing more

than multiple sentence fragments, formed by a series

of syntactic operations that involve topicalization,

focus movement, and IP-deletion”, as shown in (9a)

whose interpretation is shown in (9b) and (9c):

(9a) 问:那天在山上,他们都看见了谁?

Q: Natian zai shan-shang, tamen dou kanjian-le

shei?

that.day on mountain-above they all see-ASP

who

‘(Lit.) That day on the mountain, they all saw

whom?’

答:(?)张三看见了淑芬。李四亚萍。

A: (?)Zhangsan kanjian-le Shufen. Lisi Yaping.

Zhangsan see-ASP Shufen LisiYaping

‘Zhangsan saw Shufen and Lisi Yaping.’

Ai (2014: 126, (5))

(9b) [

TopicP

Lisi

i

[

FocusP

Yaping

j

[

IP

t

i

kanjian-le t

j

]]]

(focus movement)

(9c) [

TopicP

Lisi

i

[

FocusP

Yaping

j

[

IP

t

i

kanjian-le t

j

]]]

(PF deletion)

Ai (2014: 133, (26))

Under Ai’s analysis, the first NP, namely the

subject, is topicalized and moved from spec, IP to

spec, TopicP position. Prior to the topicalization of

李四 (Lisi), the second NP 亚萍 (Yaping) undergoes

leftward focus movement to spec, FocusP position,

which is above IP but below TopicP. Subsequently,

as shown in (9c), the remnant IP [t

i

kanjian-le t

j

] is

then deleted at the Phonetic Form, yielding (9a),

which should be notated as “张三看见了淑芬。李

四亚萍[

IP

___]” (“Zhangsan kanjian-le Shufen. Lisi,

Yaping[

IP

___]”) ‘Zhangsan saw Shufen and

LisiYaping[

IP

___]’ with the gap indicating an IP that

has been elided.

Ai’s proposal has, however, a few problems

under closer examination. First, given the

observation of given-before-new ordering of

information that has long been recognized, the

subject and object of two coordinate clauses

supposedly carry the same information function in

the sense that the subject NP usually presents the

given information, and the object NP the novel

information. Under Ai’s analysis, the subject NP and

object NP in the target clause undergo topicalization

and leftward focus movement, respectively. If Ai’s

analysis is on the right track, the antecedent clause

should undergo the same syntactic operations. This

would give rise to a distinct structure “*张三淑芬看

见了,李四亚萍” (“*Zhangsan Shufen kanjian-le,

Lisi Yaping”) ‘*Zhangsan Shufen saw and Lisi

Yaping’. Moreover, by extension, the generation of

all canonical subject-predicate-object structures

would involve such complex syntactic operations as

topicalization and focus movement, which does not

seem viable.

Second, the leftward focus movement of the

object is not properly motivated. In canonical

Mandarin sentences the object usually carries the

natural focus information as observed in Chao

(1968: 69-78). Thus, in (3) 张三吃了三个苹果,李

四四个橘子 (Zhangsan chi-le san-ge pingguo,

Lisisi-ge juzi) ‘Zhangsan ate three apples and Lisi

four oranges’, 三个苹果 (san-ge pingguo) ‘three

apples’ and 四个橘子 (si-ge juzi) ‘four oranges’ are

located in the position of informational focus, which

suggests that the leftward focus movement of the

object should not be justified. Even there exists a

focus position that is above IP and below TopicP

under certain context, there should not be any

justification for the leftward movement of the object

in gapping constructions to that position, because it

is not the only position available for focus. The

object that remains in situ is originally the natural

focus, which can become the contrastive focus when

it is phonologically stressed, namely, without

movement (see Cheng 2008).

To sum up, from an interpretive perspective, all

the analyses reviewed here fail to provide an

adequate and consistent account for the various

elliptical predicate constructions in Mandarin,

simply because their production as well as their

interpretation is context-dependent in nature.

Therefore, a proper analysis for elliptical

constructions should be one that places a high

premium on context, that is, one that can show how

syntactic processes interact with pragmatic processes

to determine the underspecified content of the

elliptical constructions.

In this paper we attempt to propose a uniform,

parsing-based account of the various elliptical

predicate constructions discussed above: Null Object

Constructions, English-like VP ellipsis and gapping

construction. From a parsing perspective, the both

syntactically and semantically underspecified

constituents can be enriched by contextual

information. The theoretical framework to be

employed is that of Dynamic Syntax (henceforth

DS, Kempson et al. 2001; Cann et al. 2005), which

is a grammar formalism that defines both

representations of content and context dynamically

and structurally and allows the interaction between

syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information.

Before presenting a DS account of elliptical

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

326

constructions in Mandarin, we provide a brief

introduction to the relevant parts of the framework

needed for handling the constructions discussed

above.

3 THE DS FRAMEWORK

The DS paradigm seeks to develop a grammar

formalism for characterizing the structural properties

of language by modeling the dynamic process of

semantic interpretation which is defined over the

left–right sequence of words uttered in context.

What is distinct about this theory is that syntactic

explanations can be grounded in the time-linear

projection of the requisite predicate-argument

structure. Like Minimalism (Chomsky 1995), there

is only one significant level of representation,

namely Logical Form. Unlike Minimalism, logical

forms are representations of semantic content, i.e.

pure representations of argument structure and other

meaningful content.

The design of the DS model reflects a number of

significant observations. First, natural language

understanding is highly dependent on context and

the change of context is not merely sentence by

sentence, but also word by word. Second,

processing, like other cognitive activities, involves

manipulation of partial information. This model

extends incomplete specifications from semantics

and pragmatics to the domain of syntax, and thus

allows the interaction between three types of actions,

computational, lexical and pragmatic, in the parsing

process. Intrinsic to this process is the concept of

underspecification, both syntactic and semantic,

which is manifested in a number of different ways

and whose resolution is driven by the notion of

requirements (i.e. goals and subgoals) which

determine the process of tree growth and must be

satisfied for a parse to be successful. The critical

aspect for the DS account will be the interaction

between these three types of actions, all of which are

expressed in the same terms of tree growth, hence

freely allowing interaction between them. Since this

interaction is important to the case to be made, we

briefly introduce the vocabulary of tree growth

decorations and the way it captures the concept of

progressive tree growth.

3.1 Requirements and Tree Growth

The starting point is to build a tree the root node of

which is the goal of interpretation formalized as a

universal requirement ?Ty(t), where ? indicates the

requirement, the label Ty the type and its value t the

type of a proposition. To satisfy such a requirement,

a parse relies on information from three sources.

First, there are computational rules that give

templates for the building of trees. A pair of general

computational rules called Introduction and

Prediction allow a tree rooted in ?Ty(Y) to be

expanded to one with an argument daughter ?Ty(X)

and a predicate daughter ?Ty(X→Y), reflecting the

functor/argument status of the typed, lambda logic

employed. By this rule, the minimal tree with the

initial requirement ?Ty(t) can be expanded to a

partial tree as in Fig. 1, where the diamond is the

‘pointer’ which is used to identify the particular

node under construction, here the external argument

or subject node

.

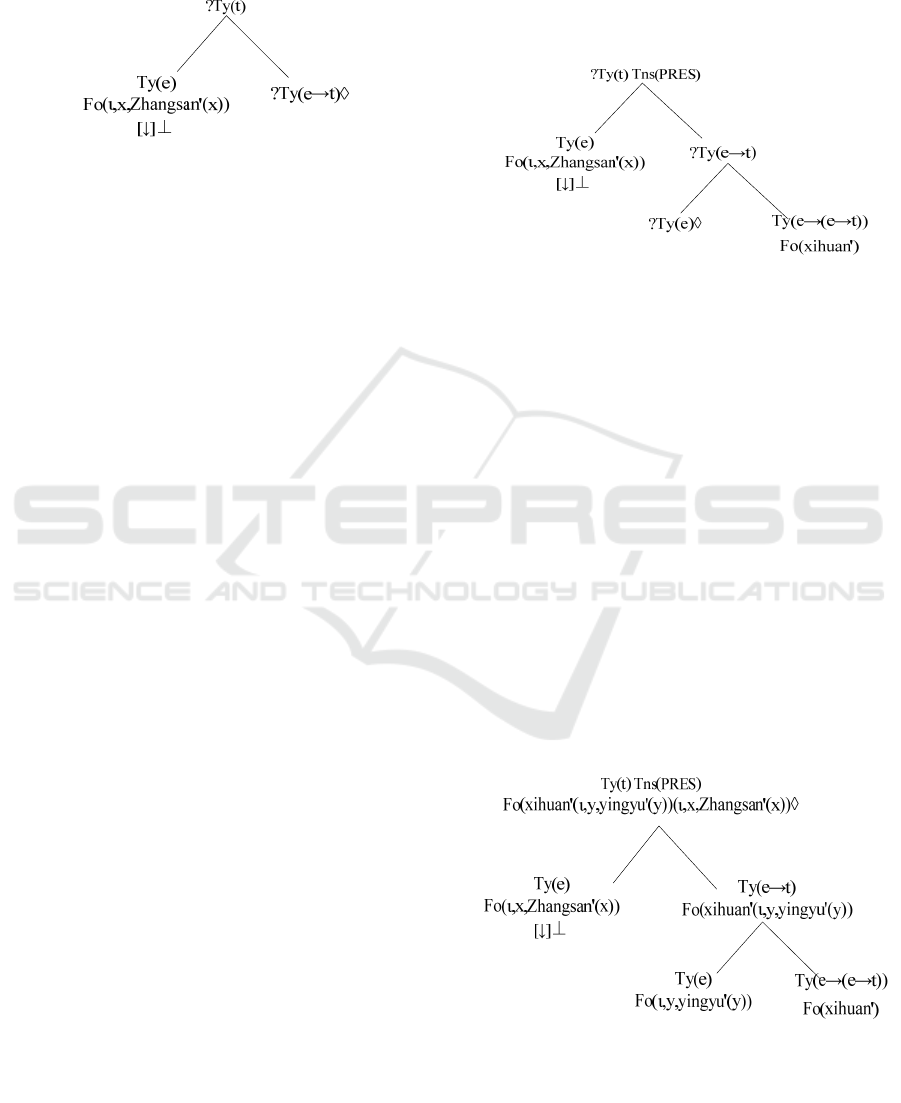

Figure 1: An initial expansion.

Second, information about tree building may

come from actions encoded in lexical entries, which

are accessed as words are parsed. Take a canonical

sentence 张三喜欢英语 (Zhangsan xihuan yingyu)

‘Zhangsan likes English’ as an example. A lexical

entry for the word 张三(Zhangsan) contains

conditional information initiated by a trigger (the

condition providing the context under which

subsequent development takes place), a set of

actions (here involving the annotation of a node with

type and formula information) and a failure

statement (an instruction to abort the parsing process

if the conditional action fails). The lexical

specification further determines, through the

annotation [↓]⊥, the so-called ‘bottom’ restriction,

that the node in question is a terminal node, a

general property of contentive lexical items

3

.

(10) Lexical entry for Zhangsan:

IF ?Ty(e)

THEN put(Ty(e), Fo(ι, x, Zhangsan'(x)), [↓]⊥))

ELSE abort

The information derived from parsing 张三

(Zhangsan) provides an annotation for the external

3

In the DS framework, proper names are treated as projecting iota

terms, where an iota term is construed as an epsilon term with an

associated unique choice function that picks out only that object

identified by the name (see Cann et al. 2005; Wu 2011).

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

327

argument node and thus satisfies the requirement on

that node for an expression of Type (e). Then the

pointer moves on to the predicate node as shown in

Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Pasring “Zhangsan”.

Lexical entries may make reference to nodes in

the tree other than the trigger node, either building

them or annotating them, by employing a few

instructions such as ‘make’, ‘put’, ‘go’, which have

obvious interpretations. To formulate both

computational and lexical actions in these terms, DS

adopts The Logic of Finite Trees (LOFT), a modal

logic for describing finite trees. This logic is central

to the DS framework and utilizes a number of

operators of which the following are used in this

paper:

〈↓〉〈↓

0

〉〈↓

1

〉〈↑〉〈↑

0

〉〈↑

1

〉〈L〉

These modalities are interpreted by a discrete

relation between the nodes in a tree: 〈 ↓ 〉 is

evaluated over the daughter relation, so〈↓

0

〉 and

〈↓

1

〉mean an argument daughter and a functor

daughter below a certain mother node respectively;

conversely〈↑〉over the mother relation, thus〈↑

0

〉and 〈↑

1

〉 mean an argument daughter and a

functor daughter of a certain mother node

respectively;〈L〉is evaluation over a relation of

‘‘LINK’’ pairing two trees. The way LOFT

operators are used can be demonstrated in the lexical

entry for 喜欢 (xihuan) ‘like’ in the above Chinese

sentence.

(11) Lexical entry for xihuan:

IF ?Ty(e→t)

THEN make(<↓

1

>), go(<↓

1

>), put(Fo(xihuan'),

Ty(e→(e→t)),[↓]⊥);go(<↑

1

>),

make(<↓

0

>), go(<↓

0

>), put(?Ty(e))

ELSE Abort

The pointer is manipulated by the lexical actions

to annotate different nodes. Firstly, it moves from

the predicate node of ?Ty(e→t) to the top node

?Ty(t) where the present tense information is

annotated, then returns to the open predicate node.

Then the lexical semantics of the transitive verb 喜

欢 (xihuan) ‘like’ takes action: it not only licenses

the building of a two-place predicate node, but also

that of an internal argument daughter with a

requirement to construct a formula of Type (e). After

the parse of the verb, the pointer moves to the ?Ty(e)

node, indicating that this is to be developed next.

The tree in Fig. 3 represents the parse state where

both the subject and the verb have been parsed.

Figure 3: Parsing “Zhangsan xihuan” ( ‘Zhangsan likes’).

Finally, the object NP 英语 (yingyu) ‘English’ is

parsed to satisfy the open term requirement in the

internal argument position, the processing of which

is the same as that of the subject NP 张三

(Zhangsan). The parsing process is not yet complete,

however, as some requirements on the tree remain to

be satisfied. Completion of the tree involves

functional application of functors over arguments,

driven by modus ponens over types, yielding

expressions which satisfy the type requirements

associated with intermediate nodes (the rules in

question are called Completion and Elimination, the

former noting modal statements of type decorations,

these then triggering the construction of the

appropriate lambda term at the mother). Fig. 4

shows the completed tree the top node of which is

decorated with a propositional formula value

representing the final result of interpreting the

utterance.

Figure 4: Parsing “Zhangsan xihuan yingyu” (‘Zhangsan

likes English’).

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

328

3.2 Anaphoric Expressions

As mentioned above, DS also allows pragmatic

actions during the parsing process, which can be

illustrated by the processing of anaphoric

expressions. Assuming the general stance that words

provide lexical actions in building up representations

of content in context, we can say that anaphoric

expressions such as pronouns may pick out some

logical term if that term is provided in the discourse

context. This sort of semantic underspecification is

treated in the DS model as involving the articulation

of anaphoric expressions as projecting a

metavariable to be replaced by some proper

representation. Put another way, anaphoric

expressions can be construed via a placeholder

which must be replaced by either some selected term

from the context or by some term given in the

construction process. Such a replacement is

established through a pragmatically driven process

of substitution which applies as part of the parsing

process.

Considering the processing of pronouns such as

she and him in the English utterance George likes

Gillian, but she doesn’t like him. In parsing the first

pronoun she, the subject node created by the rules of

Introduction and Prediction (that induce subject–

predicate structure for the conjunct clause) is first

decorated with a metavariable U

female

, with an

associated requirement ?

∃

x.Fo(x), to find a

contentful value for the formula label, as shown in

(12).

(12) IF? Ty(e)

THEN put(Ty(e), Fo(U

female

,?∃x.Fo(x), [↓]⊥)

ELSE abort

Construed in the given context, substitution will

determine that the metavariableU

female

can only pick

out the logical termFo (Gillian') established in the

first clause, since she requires to be identified with a

referent that is female or that can be attributed with

female properties. Zero anaphors (e.g. null subjects

and null objects) can be dealt with in the similar

fashion. The null object projects a matevariable,

whose value can be enriched from the context.

Essentially it is a pragmatically driven process of

substitution. We will illustrate the parsing processes

of null objects in section 4.

3.3 Linking Trees

To underpin the full array of compound structures

displayed in natural languages, DS defines a license

to build paired trees, so called Linked trees, which

are associated by means of the LINK modality, <L>.

This device is utilized for allowing incorporation

within a tree of information that is to be structurally

developed externally to it, a mechanism used for

characterizing adjuncts of various types. The

modalities are <L>, <L¯¹> and the former points to a

tree linked to the current node while the latter

naturally points backward to that node. The link

adjunction rule is illustrated as following:

Link Adjunction Rule additionally imposes a

requirement on the new linked structure that it

should contain somewhere within it a copy of the

formula that decorates the head node from which the

Link relation is projected. This rule encapsulates the

idea that the latter tree is constructed in the context

provided by the first partial tree, which thus cannot

operate on a type-incomplete node and ensures that

both structures share a term. Relative clause is one

core case analyzed employing linking trees. Besides

that, we can see later in this paper that linking tree

structure plays a significant role in the interpretation

of ellipsis constructions.

3.4 Ellipses and Context

DS is promising in the account of ellipsis

constructions, including those without linguistic

antecedents. This is because it abandons the

entrenched idea that context is irrelevant to syntax

and provides a general characterization of such

process that is blind to whether the triggering

context is internal or external to the sentence (see

Cann et al. 2007). As we mentioned, we should

place a high premium on context when dealing with

elliptical constructions. Then, we have to make it

clear: what is context? The context defined in DS

provides a record of (a) the partial tree under

construction with its semantic labels, (b) the trees

provided by previous utterances and (c) the sequence

of parsing actions used to build (a) and (b).

Moreover, context can be both linguistically and

non-linguistically. Therefore, divergent ellipsis

patterns can be explained under this approach, as

context is defined as a record of both structures and

procedures used in building up such structures, by

either re-using context-recorded content, or re-using

structure, or context-recorded actions

4

(see Cann et

4

The bonus of analyzing context as involving not only previous

content but also structures and actions used in building up these

structures can be found in the characterization of the strict and

sloppy effect mentioned in footnote 1. Copying content from

context results in the strict reading while copying the action

processes used in the antecedent clause leads to the sloppy

reading.

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

329

al. 2007; Gregoromichelaki et al. 2012 ;

Gregoromichelaki et al. 2013; Gregoromichelaki &

Kempson to appear; Kempson et al. to appear).

4 A DYNAMIC ANALYSIS

As is pointed out in section 2, the Mandarin

elliptical predicate constructions are underspecified

in content, and their interpretations are crucially

dependent on context. In the DS system, the

elliptical site projects underspecified content that is

represented by a metavariable, which may be

postulated for any type: for a Type (e) for the null

object in Null Object Construction as in (1), a Type

(e→t) for the null verb phrase in English-like VP

ellipsis as in (2), and a Type (e→(e→t))for the

empty verb in gapping construction as in (3).

Therefore, the elliptical sites in these constructions

can be uniformly analyzed as a placeholder which

requires enrichment for interpretation to occur,

through the interaction between syntactic processes

and pragmatic processes. In the case of a pronoun,

the content of the metavariable associated with it is

instantiated by a process of substitution for

interpretation, usually by a term established in the

previous discourse, as demonstrated in the preceding

section. As far as Mandarin elliptical predicate

constructions (1)-(3) are concerned, the hearer has to

identify the potential substituend for the

metavariable from the context. Therefore, with a

dynamic analysis of elliptical site as projecting a

metavariable and a technical tool for identifying its

content value from context, we should be able to

characterize Mandarin elliptical predicate

constructions in a somewhat straightforward way.

4.1 Null Object Construction

Let us first consider the Null Object Construction

(1), repeated here as (13), where the object in the

subsequent clause is unexpressed.

(13) 张三喜欢英语,李四也喜欢。

Zhangsan xihuan yingyu. Lisi ye xihuan ([e]).

Zhangsan like English Lisi also like

‘Zhangsan likes English. Lisi also likes (it).’

The interpretation of the antecedent clause 张三

喜欢英语 (Zhangsan xihuan yingyu) ‘Zhangsan

likes English’ is illustrated in section 3 as shown in

Fig. 4, repeated here as Fig.5. Introduction and

Predication rules allow a root tree to be expanded to

one with an argument node and a predicate node.

The subject 张三 (Zhangsan) is parsed and decorates

the argument node with a formula value. The lexical

information of the transitive verb 喜欢 (xihuan)

‘like’ builds a two-place predicate node (and

annotates it) and an internal argument node. 英语

(yingyu) ‘English’ is processed and annotates the

internal argument node with a formula value.

Figure 5: Parsing “Zhangsan xihuan yingyu” (‘Zhangsan

likes English’).

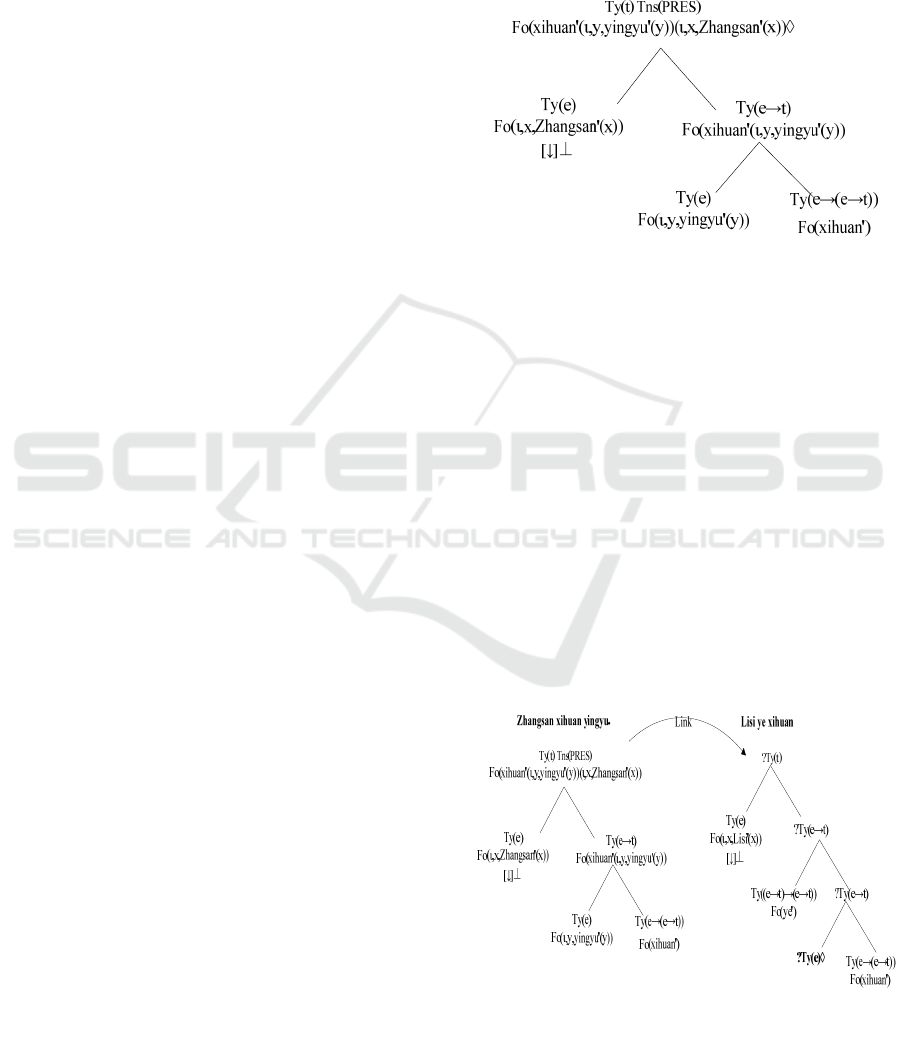

When parsing the elliptical clause, 李四 (Lisi) is

successfully parsed and duly decorates the subject

node with a formula value. The next lexical item to

be processed is however not a predicate as usually

expected, but instead a predicate adjunct 也 (ye)

‘also/too’ which can be assigned Ty((e→t)→(e→t)).

After the predicate modifier is processed, the pointer

moves to the one-place predicate node, permitting

the parse of the regular verb 喜欢 (xihuan) ‘like’,

whose lexical actions further project a two-place

predicate node decorated by Fo(xihuan') and an

internal argument node with requirements to be

satisfied. The parsing process is shown in the right

tree below in Fig.6, linked to the context tree in the

left through the technical tool “LINK” mentioned

earlier in the paper.

Figure 6: Parsing “Lisi ye xihuan” (‘Lisi also likes’).

At this point, the tree cannot be completed

because there still remains an outstanding formula

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

330

requirement on the internal argument node, which

requires a Ty(e) element. With no further strings

input, the internal argument is in its null form, which

projects a metavariable Fo(V), whose value needs to

be enriched from context.

(14) Actions for the null object:

IF ?Ty(e)

THEN put(Fo(V), ?∃x.Fo(x))

ELSE Abort

Subsequently, the pragmatic process of

substitution targets a node from the tree in the

context, selects a Ty(e) formula value and writes it

to the node decorated by the requirement ?Ty(e).

The double arrow indicates the pragmatically

constrained operation of substitution between the

linked trees. After this pragmatic process, the

requirement on the internal argument node is

replaced by some contentful concept Fo(yingyu').

The parsing process is illustrated in Fig.7,

completion of which will give rise to a propositional

formula:Fo(xihuan'(yingyu')(Zhangsan'))

∧

Fo(ye'(xi

huan'(yingyu'))(Lisi')).

Figure 7: Parsing the null object.

4.2 English-like VP Ellipsis

We now turn to English-like VP ellipsis construction

(2), repeated here as (15), which is licensed by

modal verbs such as 敢 (gan) ‘dare’, 会 (hui) ‘will’,

能 (neng) ‘can’ and so on

5

.

(15) [张三在爬树。]

[Zhangsan zai pashu.]

[Zhangsan ASP climb tree]

5

The syntactic licensing condition for English-like VP ellipsis,

namely, the restrictions on modal verbs that can license English-

like VP ellipsis constructions, is not concerned here, which will

be addressed in another papecr.

[‘Zhangsan is climbing a tree.’]

李四:我也敢。

Lisi: wo ye gan([e]).

I also dare

‘So dare I.’

The contextual utterance in (15) 张三在爬树

(Zhangsan zaipashu) ‘Zhangsan is climbing a tree’

is parsed in a normal way, with the term projected

by the subject NP 张三 (Zhangsan) decorating the

subject node, 在 (zai) as an aspect marker signalling

the progressive continuous tense, and 爬 (pa)

‘climb’ projecting a two-place predicate node (and

decorating it) and an internal argument node. The

term projected by the object NP 树 (shu) ‘tree’

finally decorates the internal argument position,

yielding a well-formed tree structure as shown in

Fig.8.

Figure 8: Parsing “Zhangsan zai pa shu” (‘Zhangsan is

climbing a tree’).

We now turn to the parse of the current utterance

我也敢 (wo ye gan) ‘I dare too’. As for the pronoun

我 (wo) ‘I’, it projects a metavariable Fo(V), whose

value can be substituted by “the speaker”. 也 (ye)

‘also/too’ is an adjunct of Ty((e→t)→(e→t)). As is

widely observed, modal verbs have certain semantic

contents, expressing the speaker’s opinions or

feelings towards the action verbs following them,

namely, they modify the verbal phrase subsequent to

them. Modals cannot be used alone as predicates,

though they can license ellipsis constructions under

certain context (with linguistic or pragmatic

antecedent). Therefore, modals such as 敢 (gan)

‘dare’ can also be analyzed as a modifier of

Ty((e→t)→(e→t)).The parsing process is illustrated

in Fig.9.

At this point, all words in the clause have been

processed, yet the tree cannot be completed because

the one-place predicate node, though type-complete,

has an outstanding requirement for a formula value.

With no further strings input, the one-place predicate

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

331

Figure 9: Parsing “wo ye gan” (‘So dare I’).

node is in its null form, which projects a

metavariable Fo(V), whose value needs to be

enriched from context.

(16) Actions for the null verbal phrase:

IF ?Ty(e→t)

THEN put(Fo(V), ?∃x.Fo(x))

ELSE Abort

The need for a contentful Ty(e→t) predicate

structure can then be satisfied through the

enrichment from context, employing the pragmatic

tool substitution. In the context of (15), the only

possible substituend for the pro-predicate is the term

Fo(pa'(ε,y,shu'(y))) projected by the preceding

verbal phrase. Subsequently, the value of the null

verbal phrase is therefore established, through an

update provided by the discourse context, parallel to

the process of the null object in Null Object

Construction. The parsing process is shown in the

tree in Fig.10, completion of which will give rise to

a propositional formula

Fo(ye'(gan'(pa'(ε,y,shu'(y))))( ι, x, Lisi'(x))).

Figure 10: Parsing the null verbal phrase.

A dynamic analysis of the null verbal phrase as

projecting a metavariable and a technical tool for

identifying its content from the context, we provided

a somewhat straightforward way to characterize

English-like VP ellipsis constructions.

4.3 Gapping

Finally, let us consider how gapping constructions in

Mandarin can be characterized. Consider example

(3), repeated here as (17).

(17) 张三吃了三个苹果,李四四个橘子。

Zhangsan chi-le san-ge pingguo, Lisi___si-ge

juzi.

Zhangsan eat-ASP three-CL apple Lisi__four-CL

orange

‘Zhangsan ate three apples, and Lisi__four

oranges.’

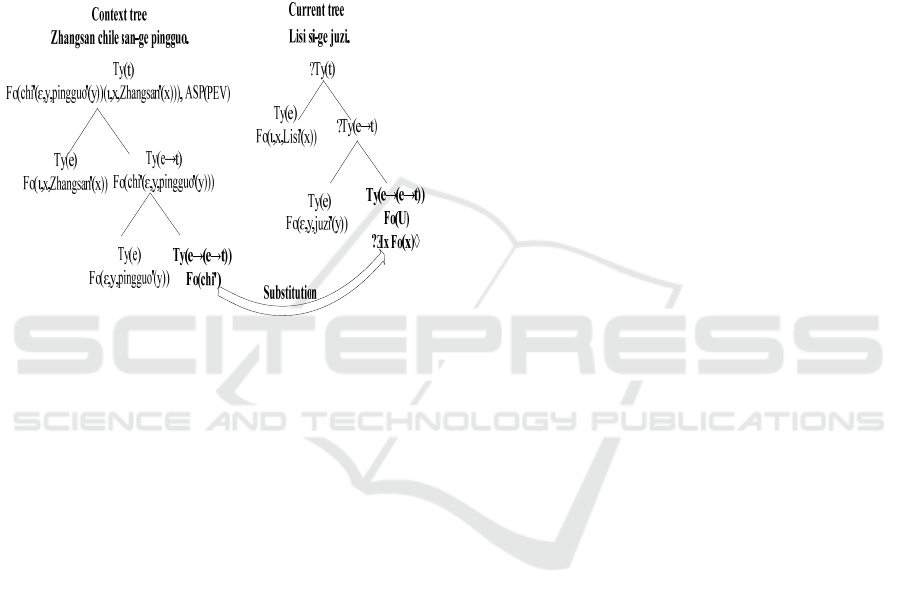

The dynamic parsing of this construction is

straightforward, without any stipulation. The parsing

of the antecedent clause 张三吃了三个苹果

(Zhangsan chi-le san-ge pingguo) ‘Zhangsan ate

three apples’ basically has the same story as that of

张三喜欢英语 (Zhangsan xihuan yingyu) ‘Zhangsan

likes English’

6

. In the subsequent clause, the pointer

moves to the predicate node after the initial

expression 李四 (Lisi) is successfully parsed and

duly decorates the subject node with a formula

value. However, the next lexical item coming in

sequence is not a predicate as usually expected, but

instead an object NP. As the antecedent clause,

namely, the context, is about eating something, we

can sense immediately that the verb in the

subsequent clause is not lexically realized, which

can be analyzed as projecting a predicate

metavaribale Fo(U), whose actions can be

characterized as below (18). Its value needs to be

enriched from context, parallel to that of the

metavariable projected by the null object in Null

Object Construction and the predicate pro-from

projected by the null verbal phrase in English-like

VP ellipsis construction.

(18) Actions for the null verb

IF ?Ty(e→t)

THEN make(<↓

1

>), go(<↓

1

>), put(Ty(e→(e→t)),

Fo(U), ?∃x.Fo(x)); go(<↑

1

>), make(<↓

0

>),

go(<↓

0

>), put(?Ty(e))

ELSE abort

6

The slight difference between these two utterances exists in the noun

phrases. The former contains a numeral phrase, the quantity

expression of which are usually represented by ε(epsilon operator)

terms.

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

332

The open requirement of a contentful value

?

∃

x.Fo(x) at this predicate node can be satisfied

through a straightforward copying of the

Ty(e→(e→t)) formula value Fo(chi') from the

context. In other words, the not-overtly expressed

verb in the subsequent clause can be easily

recovered by the verb in the antecedent clause 吃

(chi) ‘eat’. The parsing process is illustrated in the

tree structure in Fig. 11, the completion of which

will give rise to a complete formula value

Fo(chi'(ε,y,juzi'(y))(ι,x,Lisi'(x))).

Figure 11: Parsing “Lisi_si-gejuzi” (‘Lisi_four oranges’).

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

In this paper we have presented an account of a

range of Mandarin elliptical predicate constructions,

namely, Null Object Construction, English-like VP

ellipsis and gapping constructions. Within the DS

framework, which defines both representations of

content and context dynamically and structurally, the

elliptical predicate constructions are treated

uniformly in the way that the underspecified

contents are all enriched pragmatically from the

context through the process of substitution. The

null object in Null Object Construction, the null verb

phrase in English-like VP ellipsis as well as the null

verb in gaping construction are consistently

analyzed as a metavariable, projecting nodes with

underspecified semantic contents which are

informationally updated from context. The context

involves local (as in (1) and (3)) as well as extra-

linguistic content (as in (2)). It is thus shown that

syntactic and pragmatic processes interact to provide

a straightforward and unitary characterization for a

variety of elliptical predicate constructions in

Mandarin, without any stipulation.

REFERENCES

Ai, R.-X. R. 2008. Elliptical Predicate Constructions in

Mandarin.Muenchen: Lincom.

Ai, R.-X. R. 2014. Topic-comment structure, focus

movement, and gapping formation. Linguistic Inquiry

45(1), 125-145.

Cann, R., Kempson, R., & Marten, L. 2005. The Dynamics

of Language. Oxford: Elsevier.

Cann, R., Kempson, R., &Purver, M. 2007. Context and

Well-formedness: the Dynamics of Ellipsis. Research

in Language and Computation 5, 333-358.

Chao, Y. R. 1968.A Grammar of Spoken Chinese.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cheng, L.-S. L. 2008. Deconstructing the shi...de

construction. The Linguistic Review 25, 235–266.

Chomsky, N. 1995.The Minimalist Program. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press.

Gregoromichelaki, E., Cann, R., &Kempson, R. 2013. On

coordination in dialogue: subsentential talk and its

implications. In: L. Goldstein, ed. On Brevity.Oxford

University Press.

Gregoromichelaki, E., &Kempson, R. to appear. Joint

utterances and the (split-)turn taking puzzle. In: L. M.

Jacob & A. Capone, eds.Interdisciplinary studies in

Pragmatics, Culture and Society. Heidelberg:

Springer.

Gregoromichelaki, E., Kempson, R., &Cann, R. 2012.

Language as tools for interaction: Grammar and the

dynamics of ellipsis resolution. The Linguistic Review

29(4), 563-584.

Hankamer, J., & Sag, I. 1976. Deep and surface

anaphora.Linguistic Inquiry 7(3), 391-426.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1991a. Remarks on the status of the null

object. In: R. Freidin, ed. Principles and Parameters

in Comparative Grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press, 56-76.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1991b. On Verb Movement and Some

Syntax-Semantics Mismatches in Chinese, in

Proceedings of the 2

nd

International Symposium of

Chinese Languages and Linguistics, Academia Sinica,

Taipei, Taiwan.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1997. On Lexical Structure and Syntactic

Projection, in Chinese Languages and Linguistics III:

morphology and lexicon, Symposium Series of the

Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica,

No.2. Taipei, Taiwan, 45-89.

Johnson, K. 1994. Bridging the gap. Ms., University of

Massachusetts, Amherst.

Johnson, K. 2004. In search of the English middle

field.Ms., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Johnson, K. 2006. Too many an example is thought to be

ellipsis, and too few, across-the-board movement.

Invited talk given at MIT Colloquium, 17 February.

Johnson, K. 2009. Gapping is not (VP-) ellipsis. Linguistic

Inquiry 40, 289–328.

Kempson, R., Cann, R.,Eshghi, A.,Gregoromichelaki,

E.,&Purver, M.to appear. Ellipsis. In: S. Lappin and C.

Fox, eds.The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic

Theory.2

nd

Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

The Interpretation of Elliptical Predicate Constructions in Mandarin: Semantic Underspecification and Pragmatic Enrichment

333

Kempson, R., Meyer-Viol, W., & Gabbay, D.

2001.Dynamic Syntax: The Flow of Language

Understanding. Oxford: Blackwell.

Li, H.-J. G. 2002. Ellipsis Constructions in

Chinese.University of Southern California.

Li, Y.-H. A. 2005. Ellipsis and Missing Objects.Language

Science (4), 3-19.

Tang, S. W. 2001. The (non-) existence of gapping in

Chinese and its implications for the theory of

gapping.Journal of East Asian Linguistics 10, 201–

224.

Wu, Y. C. 2011. The interpretation of copular

constructions in Chinese: Semantic underspecification

and pragmatic enrichment. Lingua 121(5), 851-870.

Xu, L. J. 2003. Remarks on VP-ellipsis in disguise.

Linguistic Inquiry 34(1), 163-171.

PUaNLP 2016 - Special Session on Partiality, Underspecification, and Natural Language Processing

334