Automated Assistance in Evaluating the Design of On-screen

Presentations

Karin Harbusch, Denise D

¨

unnebier and Denis Krusko

Computer Science Department, University of Koblenz-Landau, Koblenz, Germany

Keywords:

Human-computer Interaction, Interface Design, Personalized Feedback, Presentation Design, Presentation

Layout, Evaluation Assistant System.

Abstract:

Oral presentations can profit decisively from high-quality layout of the accompanying on-screen presentation.

Many oral talks fail to reach their audience due to overloaded slides, drawings with insufficient contrast, and

other layout issues. In the area of web design, assistant systems are available nowadays which automatically

check layout and style of web pages. In this paper, we introduce a tool whose application can help non-experts

as well as presentation professionals to automatically evaluate important aspects of the layout and design of

on-screen presentations. The system informs the user about layout-rule violation in a self-explanatory manner,

if needed with supplementary visualizations. The paper describes a prototype that checks important general

guidelines and standards for effective presentations. We believe that the system exemplifies a high-potential

new application area for human-computer interaction and expert-assistance systems.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the onset of their oral presentations, speakers

sometimes apologize for the potentially suboptimal

quality of the accompanying visual slides

1

. They

wonder whether the audience can see presented

curves although the contrast between foreground and

background is poor, e.g., yellow on white back-

ground, or whether the people in the back can read

10pt fonts well enough. These and similar questions

are meant to be rhetorical—the audience often per-

ceives them as cynical.

Could assistant systems inspect slides while the

talk and the accompanying audiovisual aids are being

prepared? In many areas of human-computer inter-

action, such as web-site design, assistant systems are

available nowadays but, to our knowledge, not in the

area of audiovisual presentations. The present paper

describes a prototype that automatically checks vari-

ous general guidelines and standards for effective au-

diovisual presentations.

In our system, short traffic-light-style bars inform

the user about the evaluation result—supplemented

on demand by more elaborate explanations. In the list

of preferences, the user can deselect features s/he is

1

Although true “slide” projection is hardly in use anymore,

the term slide has survived the transition from physical to

virtual overheads.

not interested in along with personalized values over-

writing the system’s defaults. For instance, the slides

may contain more information in an academic lec-

ture than in a business talk. In this paper, we focus

on visualization of feedback by a system that has de-

tected violations of presentation rules and standards.

We describe measures taken to facilitate system use

by novices as well as experts. The implementation of

algorithms such as calculating the density of a slide or

detecting insufficient contrast levels is not discussed

here.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next sec-

tion, we sketch the state of the art in assistant systems.

In Section 3, we specify important to-be-evaluated

criteria in the area of (audio)visual presentation de-

sign. The current prototype is discussed in Section 4.

In the final section, we draw some conclusions and

address future work.

2 STATE OF THE ART IN

ASSISTANT SYSTEMS

Automated assistance in user-interface design is a rel-

atively young but dynamic field. Goal is to counter-

vail the proliferation of poorly designed interfaces—a

development spawned by easy-to–use tools for imple-

Harbusch, K., Dünnebier, D. and Krusko, D.

Automated Assistance in Evaluating the Design of On-screen Presentations.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 451-458

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

451

menting dialogue systems. An important early step in

this direction constitutes the DON framework (Kim

and Foley, 1993), which uses rules from a knowledge

base to provide expert assistance in user-dialogue de-

sign. It can generate layout variants in a consistent

manner. Subsequent development of such assistant

systems proceeded in two main directions—graphic

art (printing) and web—, and has already given rise

to expert-assistant systems with commercial applica-

tions.

In the graphic-arts industry, quality control before

printing plays a crucial role by reducing the costs of

reprinting. The process has been dubbed “preflight”.

This term usually designates the process of preparing

a digital document for final output as print or plate,

or for export to other digital document formats. The

first commercial application was “FlightCheck”

2

de-

scribed in a paper entitled “Device and method for

examining, verifying, correcting and approving elec-

tronic documents prior to printing, transmission or

recording” (Crandall and Marchese, 1999). Recent

products in the area provide integrated preflight func-

tionality (see, e.g., Adobe InDesign

3

and Adobe Ac-

robat

4

). The main objective of these instruments is

to reveal possible technical problems of the docu-

ment. Accordingly, they work with the following pri-

mary checklist: (1) Fonts are accessible, compatible

and intact; (2) Media formats and resolution are con-

forming; (3) Inspection of colors (detection of incor-

rect/spot colors, transparent areas); (4) Page informa-

tion, margins and document size.

According to Montero, Vanderdonckt & Lozano

(2005), the abundance of web pages with poor usabil-

ity is largely due to shortage of technical experts in

the field of web design. Ivory, Mancoff & Le (2003)

present an overview of systems that are capable of

analyzing various aspects of the web pages. Histor-

ically different browsers have different views on the

implementation of web standards (see, e.g., Windrum,

2004), with as a consequence that the same web page

may look differently in different web browsers. The

above criteria have led to the situation that tools for

web-page analysis focus primarily on technical and

marketing aspects of the pages. Current web analysis

tools primarily check:

• W3C

5

DOM, HTML and CSS standards;

2

FlightCheck (Preflight for Print), http://markz

ware.com/products/flightcheck (Nov. 11, 2015).

3

Adobe InDesign CC, http://www.adobe.com/products/ in-

design (Nov. 11, 2015).

4

Adobe Acrobat, https://acrobat.adobe.com (Nov. 11,

2015).

5

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), http://www.w3.org

(Nov. 11, 2015).

• Search engine optimization (SEO) aspects;

• Web page performance and rendering speed;

• Content, media and script sizes;

• Accessibility of various devices.

Despite the emphasis on purely technical aspects,

several publications report on systems assisting users

on other aspects of web design (e.g., Tobar et al.,

2008). Some state-of-the-art systems (see, e.g., Nagy,

2013) advise on visible content prioritizing, check the

size of control elements (e.g., some dialogue items

may be too small for using on mobile devices), and

distances between the visible elements of a web page.

An essential question concerns whether or not

assistant systems should react directly/online, in a

daemon-like fashion, to any undesirable user action

(maybe even forbidding and overruling user actions),

or should become active only on demand. The major-

ity of systems mentioned above prefer the on-demand

dialogue. Basically, the decision depends on the as-

pect evaluated. For instance, if the system cannot re-

act to a user action such as saving a file in the cur-

rent format, the implication should be brought to the

user’s attention. The online alternative is appropri-

ate if no ill-formed result can be produced at all (e.g.,

automatic typo correction during SMS typing, which

avoids unknown words). However, this mode may

cause the user to feel patronized. As a consequence,

users tend to switch off such components. The sec-

ond alternative of giving advice on demand offers the

user more freedom (e.g., new words can be typed). In

design, the user even might intentionally violate rules

as a stylistic matter (cf. provocative design).

3 PRESENTATION RULES

Here we summarize well-known standards for user-

interface design in general, which also apply to the

design of on-screen presentations. Additionally, we

list rules of thumb specifically for presentation de-

sign in particular. Due to space limitations, we cannot

give a comprehensive overview of such rules and stan-

dards, and instead focus on the type of rules that our

system checks automatically.

Many user-interface design rules (cf. the EN ISO

9241 norm) can be applied to slide presentations as

well: use only few different colors; avoid high color

saturation levels; give sufficient contrast to the col-

ors used; group related elements together, potentially

with a frame around them, and/or make sure there

is sufficient spacing between non-related items (cf.

the Gestalt laws; see Wertheimer’s work reprinted in

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

452

2012); do not make the interface too crowded; dis-

tribute objects such that the virtually assumed grid

lines are minimized (i.e. make the interface—in our

case, the slides—look balanced and sophisticated; cf.

Galitz, 2007). The recommendation not to overtax

the short-term memory of the user in interface de-

sign also holds for a slide: it restricts the number of

presented items to 7+/- 2 per slide (cf. Miller’s rule;

Miller, 1956). In total, no more than 30% to 40% of

a slide’s surface should be occupied (cf. the screen

density suggestion by Galitz, 2007).

For consistency reasons (cf. Shneiderman and

Plaisant, 2004), font, size, position and color of the

slides should remain the same in publishing media.

This holds in particular for the title. Moreover, the

latter’s position should remain the same on each slide.

Often a predefined frame is assumed for a user inter-

face (cf. the slide master in PowerPoint

6

for the adap-

tation to visual presentations).

Specific rules for visual-presentation design are

discussed in many books. A wide variaty of books fo-

cuses on different user needs such as presentation for

beginning or professional presenters in business. For

instance, for non-designers, Robin Williams (2015)

cites four principles of visual presentation design: (1)

Contrast, (2) Repetition, (3) Alignment, and (4) Prox-

imity.

We focus on the following rules of thumb that, we

assume, hold for business presentations. They repre-

sent the defaults of our prototype:

(1) Do not use more than two font types in a presen-

tation

7

;

(2) Do not use fonts smaller than 18pt;

(3) Do not use more than three colors;

(4) Avoid saturated colors (threshold 30%);

(5) Provide sufficient contrast for chosen colors/gray

values (threshold 10%);

(6) Provide sufficient distance between unrelated ob-

jects (as opposed to related objects which should

be closer together due to Gestalt law effects; hor-

izontal = .8cm, vertical = .8cm

8

);

(7) Provide a balanced distribution of elements (max-

imum number of grid lines = 20 with unified dis-

tance of .3cm);

6

See PowerPoint, http://products.office.com/powerpoint

(Nov. 12, 2015).

7

An extended version also checks whether dispreferred

fonts are being used (e.g. Antiqua; for pros and cons of

various fonts, see, e.g., Williams, 2015). Our default list is

based on Schildt and K

¨

ursteiner (2006). The user can edit

this list (as s/he can modify any default parameter of the

system).

8

These values can also be calculated automatically using

the font size used in the currently considered text box (cf.

Galitz, 2007).

(8) Slides should not be too full (threshold for overall

slide density = 30%).

(9) For convenience of the audience, provide auto-

matic print versions without images, and/or with

inversion of dark to white background and au-

tomatic conversion of the foreground colors to

black or a user-defined value. This mode is not

discussed here for reasons of space.

As will be outlined in the next section, the above

mentioned features are first checked for each slide

separately, using the default or user-defined parameter

settings. The per-slide evaluation reports are subse-

quently inspected for overall consistency of the entire

presentation.

4 SEAP TOOL: A PRESENTATION

ASSISTANT SYSTEM

The nick name SEAP stands for Software-Ergonomic

Analysis of Presentations. First, we describe SEAP

tool’s system design, e.g., its input and output struc-

tures. Then, we focus on the inspection per slide. In

Section 4.3, we elaborate on the preferences the user

can express for any feature in any particular slide.

Section 4.4 indicates how the contents of the per-slide

evaluation report are used for checking the overall

consistency of the presentation.

4.1 System Design

Our prototype is implemented in Java 8

9

. As

the main input format, we use Portable Docu-

ment Format (PDF), being the de facto standard for

fixed-format electronic documents (cf. ISO 32000-

1:2008

10

). Hence, the system can analyze any pre-

sentation that is exportable as PDF, irrespective of the

slide preparation program or the operating system un-

der which the presentation was created.

The PDF format also permits access to the pre-

sentation’s internal content stored as text, as raster or

vector graphics, or as multimedia objects. If avail-

able, we use this information in the subsequent slide

analyses. However, an analyzed slide may consist

of only a picture, without any text information (e.g.,

when the entire slide is a screenshot). In this case, or

when graphical elements on the slide display text, we

9

Java Software, https://www.oracle.com/java/index.html

(Nov. 12, 2015).

10

See http://www.iso.org/iso/iso catalogue/catalogue tc/cat

alogue detail.htm?csnumber=51502(Nov. 12, 2015).

Automated Assistance in Evaluating the Design of On-screen Presentations

453

use the computer vision library OpenCV

11

to identify

the objects. Obviously, this variant is computation-

ally more complex and more time consuming. This

will be reflected in lower processing speed, especially

when producing evaluation reports on larger input

files. However, the system thus gains independence

from the actual representation format of the content

of the slide. In the following, we do not elaborate

on implementation details of the two different meth-

ods to obtain an evaluation result. (See D

¨

unnebier,

2015; this paper also discusses quality estimates of

the evaluation algorithms applied in SEAP. Without

going into details, we assume that the evaluation re-

sults to be discussed below can be calculated automat-

ically.)

Given the decision to inspect a PDF file of the pre-

sentation, the way SEAP tool provides the output is

also determined. As mentioned in Section 2, an assis-

tant system can evaluate online during the design pro-

cess, or produce a review on demand. The latter (also

SEAP’s) mode has the advantage of avoiding disturb-

ing the user, especially during stages where the focus

is on content rather than form. However, this decision

has a drawback: information that would be immedi-

ately at hand online (e.g.: Which areas belong to the

master slide? Which text box is meant to be the title?)

has to be recomputed.

We target different user groups: not only novices

but also presentation professionals. Basically, the re-

port aims at easily understandable comments (e.g.,

visualizations rather than technical terms in case of

novice users). Professionals receive short traffic-

light-style comments only.

Moreover, the personal settings for all parameters

of the individual evaluation algorithms allow differ-

ent levels of detail. Inexperienced users see intuitive

labels, professional users can operate an “Advanced”

button to enter exact values (e.g., see Figure 6 in Sec-

tion 4.3 for the interface enabling personalization of

the grid inspection parameters).

In the next paragraph, we outline the evaluation of

individual slides, focusing on user preferences.

4.2 Report Generation per Slide

In reports on the evaluation of specific features, a

green or red background indicates successful or fail-

ing compliance with the relevant rules. This traffic-

light-style information helps professional users to

speed up reading—on the assumption they search for

red bars only (cf. Figure 1). It also supports users who

are unfamiliar with presentation rules. They can read

11

OpenCV (Open Source Computer Vision),

http://opencv.org (Nov. 12, 2015).

the traffic-light colors as hints whether they are on the

right track or not. Moreover, we present informative

visualizations whenever possible. If desired, the re-

port can become personalized in two respects:

(1) The user has the option to define personal prefer-

ences overruling the default settings used by the

underlying algorithms.

(2) Additionally, the system offers the choice be-

tween concise or elaborate reporting.

Figure 1: Concise analysis report. The user has asked the

system to check the number of used fonts and the screen

density only: Positive feedback for used fonts is displayed

against a green background, negative feedback on crowded-

ness against a red background.

In the following, we focus on the elaborate re-

porting mode. On each slide, SEAP tool counts the

number of different fonts and compares it against the

threshold (whose default value is two). It also checks

the occurrence of user-defined but generally dispre-

ferred fonts. Figure 2 illustrates the most elaborate

version of a font warning generated by SEAP tool.

Color saturation warnings and warning for too many

different colors on the same slide look similar. For

reasons of space, we skip details here.

Figure 2: Elaborate font information based on the yellow

rule of thumb in the right panel.

Whenever possible, visualizations are used to in-

form the user in a self-explanatory manner so that pro-

fessional as well as non-professional presenters can

use the system. For instance, the system exemplifies

whether closely neighboring objects are likely per-

ceived as belonging together according to the Gestalt

laws. The system groups such objects in one abstract

box

12

, in line with the default or user-defined thresh-

12

In this figure, we use black as the color denoting such

boxes because this yields better interpretability of the

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

454

old (cf. Figure 3

13

corresponding to the slide depicted

in Figure 1). Notice that, here, the system does not

attempt to warn against errors but merely visualizes

the grouping most likely perceived by the audience.

Therefore, only the user—not the system—can adapt

the slide to the intended content. The example de-

picted in the figure also illustrates the difference be-

tween PDF-based and image-based inspections. In

the PDF file, the two text items are shown in one

box (see the green text boxes in the grid representa-

tion of Figure 4: they reflect the predefined settings

for highlighting text compared to images, as outlined

in Figure 6 in the next subsection). However, given

the current threshold settings, an image analysis of

the slide would interpret the text items as two inde-

pendent boxes. Consequently, the user might feel

inclined to improve the slide by positioning the two

text items closer together. In SEAP tool, we currently

take the PDF information about text to determine text

boxes. Thus, no conflict needs to be resolved.

Figure 3: Recognition of object groupings for a threshold

bigger than the distance between the text box with the two

items and the two images but smaller than the distance be-

tween the two images.

In a similar manner, the system can visualize

whether the spatial distribution of objects is balanced

giving the impression that the user has immersed

in the presentation design. Such visualizations dis-

play the virtual grid based on a threshold determin-

ing which distance is assumed to be one unit. For

instance, on the slide in Figure 1, the two images are

not fully vertically aligned (cf. Footnote 13). A very

exact threshold (e.g., .1cm) would show two vertical

grid lines to the left, and two vertical grid lines to the

scaled-down image. In SEAP tool, the user can select

any color and any level of transparency.

13

The obvious grid violation of an exact vertical alignment

of the two images is intentional here. We will use the

same image for the purpose of illustrating the virtual grid

calculation later on in the section. One can see that the

default parameter for grid inspection can be considerably

high. Obviously, the original slide as presented in Fig-

ure 1 looks balanced.

right of the images. If the threshold would be set to

a more lenient (higher) value, only one grid line will

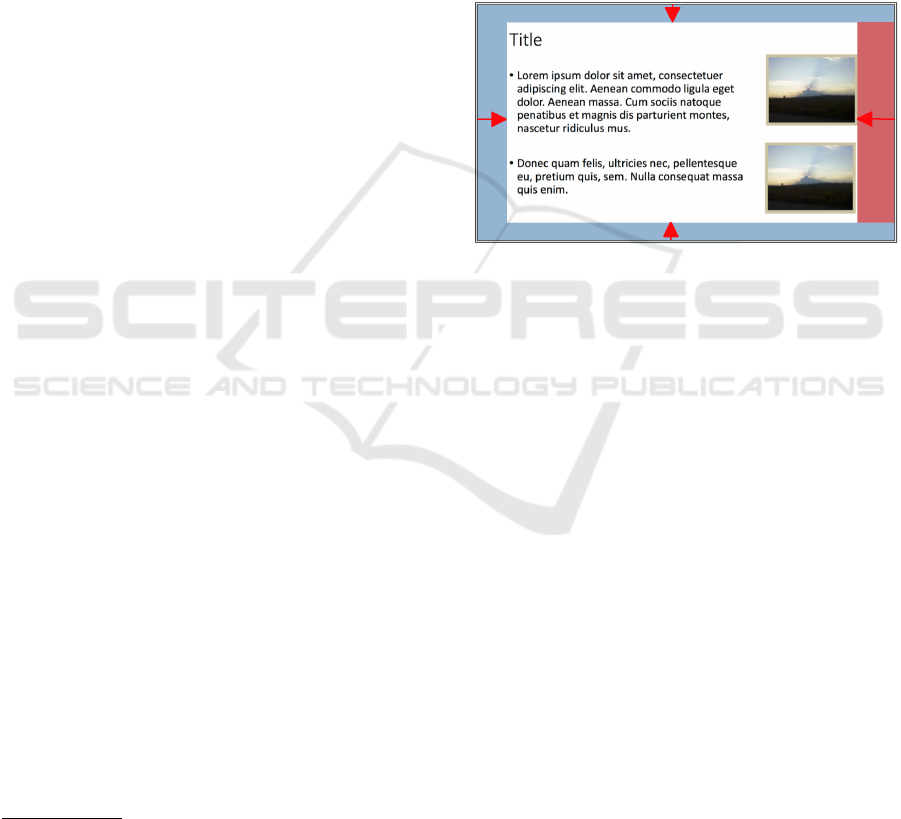

be calculated. Figure 4 depicts the result when an ex-

act threshold is used: this illustrates the power of the

automatic calculation. As holds for all preferences

of SEAP tool, the color of boxes and lines serving to

highlight the meta information on a slide can be cho-

sen by the user. Thus, object colors and background

colors on the slide can be clearly distinguished from

colors added by SEAP tool in the the evaluation in-

formation.

Title

• Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer

adipiscing elit. Aenean commodo ligula eget

dolor. Aenean massa. Cum sociis natoque

penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes,

nascetur ridiculus mus.

• Donec quam felis, ultricies nec, pellentesque

eu, pretium quis, sem. Nulla consequat massa

quis enim.

Figure 4: Visualization of the grid lines of objects illustrat-

ing whether the order of objects is reduced or not.

As for contrast evaluation against a given thresh-

old, in the current SEAP tool version, each slide

is translated into a grayscale version by applying a

black-and-white filter, e.g., a dithering algorithm

14

.

The concise report can issue warnings that infor-

mation with too low contrast has disappeared. Too

close similarities between colors can also be detected

if the threshold is refined. In the elaborate report

version, slide areas with “missing information” are

highlighted, so that the user does not easily over-

look missed details. Currently, we run experiments

with measured contrast levels indicated directly on

the original slide, without applying a black-and-white

filter. Additionally, new evaluation rules should be

added enabling the detection of colors invisible to

color-blind users.

In the next paragraph, we discuss how user-

defined preferences are entered. Here, it is im-

portant to use terminology that any kind of user

understands—not only experts.

4.3 User-specific Preference-dialogues

for Individual Slide Inspection

In this section, we introduce parameter settings for the

14

For an easily understandable and nicely visu-

ally supported description see http://www.tanner

helland.com/4660/dithering-eleven-algorithms-source-

code/ (Nov. 12, 2015).

Automated Assistance in Evaluating the Design of On-screen Presentations

455

inspection of individual slides. The user can define

slide-specific defaults as well as presentation-general

ones. The latter ones are discussed in the separate

Section 4.4 because checks of overall consistency are

based on the per-slide reports. Moreover, the prefer-

ence menu includes a separate submenu for the over-

all presentation parameters. This submenu also al-

lows skipping the final overall evaluation when the

user is not interested in this inspection, or when s/he

is finalizing the presentation.

For each individual slide, the user can select which

features to evaluate. This can speed up the process

considerably

15

. Moreover, the user may be interested

in specific feedback only. In that case, s/he is pre-

sented with the list of options mentioned in Section

3, and invited to select or deselect one or more items.

Deselected items are grayed out and move to the end

of the list. This behavior should elicit another user-

option available in this window: The user can change

the ordering of the sections in the evaluation report.

In the top of the window, the user is informed that the

list can be re-ordered if desired. In Figure 5, the win-

dow is depicted in the original order. However, the

figure illustrates a state where the user has deselected

the last five items (cf. gray color). Of course, any

choice and ordering can be revised before being ap-

plied. Pushing the “Abort” button means staying with

the previous settings. Pushing the preselected “Ap-

ply” button adapts the evaluation report according to

the user’s preferences.

After the user has left the window either by push-

ing the “Apply” or the “Abort” button, s/he can opt for

a concise or an elaborate report on each of the remain-

ing items, to be displayed in the subsequent window.

This window contains a choice button enabling rever-

sal of the default assumed at the start. The default is

to provide an elaborate report, for we assume that, in

the beginning, the user—irrespective whether s/he is a

novice or a professional presenter—will take the time

to get familiar with SEAP tool’s feedback behavior.

For reasons of space, we will not discuss this window

here.

Besides the dialogue about the overall order and

level of detail of the report, the user can overwrite

the default parameter setting of any feature chosen

to be checked in the report. Menu items referring

to deselected evaluation features remain inactive (de-

picted in gray). We always display these menu items

in the same order irrespective to the report order cho-

15

Notice that the evaluation report also contains a section

for the overall presentation checking (see next section).

If the user wants many general consistency features to

be checked according to personal preferences, the system

obviously can not speed up very much.

Figure 5: Personalization of features to be evaluated along

with the option to personalize the order of results presented

in the report.

sen by the user, because we assume search in a fixed-

order menu is faster. Figure 6 shows an example that

avoids changing exact numbers—which we assume to

be the desired mode for novices. The example illus-

trates how inexperienced presenters can work with the

SEAP tool in an intuitive fashion. Abstract terms in-

stead of exact values are shown to allow the user to

make a meaningful choice. Experts probably prefer

a window where they can change the default values

directly. The current prototype is not able to present

the full set of possible menus for all features. We are

currently revising and extending these dialogues con-

siderably for the next version of SEAP tool.

Figure 6: Upper part of the dialogue window: Setting of the

grid evaluation parameter in the preferences list in a man-

ner that allows inexperienced users to make a meaningful

choices. Lower part: The button labeled “Advanced” lo-

cated above the final choice “Abort/Apply” opens a window

presenting detailed numerical settings, intended to be used

by experts.

All defaults mentioned in Section 3 can be over-

written. Furthermore, the list of non-accepted fonts

can be modified. For reasons of space, we do not elab-

orate on the fact that there are predefined forbidden

values (e.g., using no more than zero different fonts).

Of course, the algorithms activated during the evalua-

tion process first check explicitly whether the ranges

set by the user are acceptable. Otherwise, the system

would crash unexpectedly.

Based on all these settings, the user gets a review

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

456

per slide in his/her personal style (e.g., a brief traffic-

light-style coding for some selected features only). In

its most elaborate mode, the report sums up positive

and negative evaluation results for all inspected fea-

tures. Additionally, it can provide hints on why/how

the slide should be changed.

In the next section, we describe how the per-slide

evaluation reports are consulted in order to detect

overall consistency violations

4.4 Evaluation of Overall Consistency

In this section we discuss features that can be checked

for consistency across the entire set of slides—e.g.

whether or not the same fonts have been used through-

out the presentation. The user can switch this evalu-

ation on/off in the same manner as the features to be

checked per slide.

If the user wants a consistency check, the user gets

an overview of slides exhibiting rule/standard viola-

tions. The visible and invisible information in the per-

slide evaluation reports enables the system to produce

such a report automatically. However, the system

needs additional information about the presentation in

order to perform more advanced jobs, such as the fol-

lowing. SEAP tool should know about facts such as

a predefined title position. Although this is known at

design time, it is not accessible in the PDF file serv-

ing as input. The system assumes as default a mar-

gin area of 1cm around the presentation area. SEAP

tool does not presuppose a specific, dedicated title

area preset by the system, because warnings about

any violation would irritate users who have no idea

where the system assumes the title to be—there are

no user expectations the system can take for granted.

These (minimal) default settings avoid an obligatory

dialogue with the user before running the system.

As holds for any preference in SEAP tool, the user

can change these defaults in special windows. Here,

the user can also define areas that the system should

inspect for identity vs. leave uninspected for iden-

tity

16

. Figure 7 illustrates the assembly of a slide mas-

ter. This example corresponds to the slide in Figure 1

where only margins as slide master is assumed—to be

identical/ignored over all slides. The individual mar-

gin areas can be varied as indicated by the red arrows

shown in the middle of each 1cm default margin. The

inspection method carries out an identity check by de-

16

The current version of SEAP tool applies an exact match

algorithm. However, we are aware of the fact that the

match should be less exact, e.g. in order to license slide

numbers or small color/size variation serving to highlight

parts of the currently active content. These and other sim-

ilar tiny differences should not count as non-identical.

fault. We omit the dialogue to select between the op-

tions of ignoring an area vs. matching it throughout

the presentation. This choice window pops up when

activating the red arrow in an area or when double-

clicking on the area. As a consequence, the color

of the region changes. Blue means “check exactly”,

whereas red means “ignore the content completely”.

Preliminary experiments show handiness of the con-

cept in the right vertical periphery—as is depicted as

desired personalized setting in Figure 7. This setting

allows the user to violate the right margin supposed to

be identical with the master slide intentionally due to

longer lines.

Figure 7: User interface enabling the user to determine the

master-slide area in the presentation by varying the default

area to be matched exactly on all slides or to be ignored on

all slides. The areas in blue reflect the wish for an exact

match and the ones in red, for ignoring any difference in the

chosen rectangle.

The title area can be specified in a similar interac-

tive window. Of course, title checks need not be ex-

act: The user can determine which features should be

checked (defaults are font type, font size and color).

The same type of dialogue window opens if the user

wants to have additional areas checked for consis-

tency (e.g., slide numbers). In these windows, the

blue areas needs unique field labels to be used in

the evaluation report for these areas. The same pa-

rameterized procedure inspects the title area as well

as the user-defined areas (parameters: name, coordi-

nates and features to be checked throughout the pre-

sentation). These inspections are based on informa-

tion contained in the elaborate form of the per-slide

evaluation reports.

Finally, SEAP tool draws up the consistency-

check summary and presents it to the user. It results

from a final review of all internal entries in the per-

slide evaluation reports for each feature the user wants

to be checked globally. For instance, the system can

generate warnings in the final summary such as ‘At-

tention, on slide 4, the font of the title is inconsistent.

Please change from Times to Arial’.

Automated Assistance in Evaluating the Design of On-screen Presentations

457

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have sketched the prototype of an assistant sys-

tem for layout and design evaluation of on-screen pre-

sentations. We have illustrated the diversity of topics

automatically checked by our system. Such a system

seems desirable as a tool to improve the quality of (au-

dio)visual presentations in science and business given

the often poor quality of presentations in science and

business.

Our system, called SEAP tool, evaluates visual

presentations against well-known rules and standards.

It takes the PDF file of a presentation as input, thus

making it independent from the software used to cre-

ate the presentation. SEAP tool performs specific

inspections on the PDF format, but other analyses

are based on an image representation of each slide.

Based on these results, the system draws up an eval-

uation report for each slide in a personalized man-

ner. The user can determine which features should

be evaluated, and in which order the results should

be reported. In addition, the various parameters for

the evaluation calculations can be personalized, along

with the levels of detail of the reports. At the end, the

user can activate an overall consistency check of the

entire presentation.

As for future work, we plan to implement addi-

tional rules of presentation design and layout. For

instance, as announced in Section 4.2, a facility for

color-blind proof-reading of slides should be avail-

able. Furthermore, the image analysis techniques

deployed by SEAP tool need further improvement.

Moreover, the existing components such as the color

checks that currently work with a translation into a

grayscale will have to be improved.

Most important are user studies with novices and

professionals, helping us to obtain better assessments

of user needs and appreciations, and to optimize the

user interface. We paid attention to the fact that the

dialogues are easily comprehended even by novices.

In this regard, we supported text with intuitive visual-

izations. However, only an empirical user study can

provide clear insights into how the user interface can

be optimized, and which to-be-evaluated features they

value most.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are greatly indebted to Gerard Kempen for de-

tailed and constructive comments on a preliminary

version of the paper.

REFERENCES

Crandall, R. and Marchese, P. G. (1999). Device and

method for examining, verifying, correcting and ap-

proving electronic documents prior to printing, trans-

mission or recording. US Patent 5,963,641.

D

¨

unnebier, D. (2015). Software-gest

¨

utzte Generierung

von ergonomischen Verbesserungsvorschl

¨

agen zur

Darstellung von Pr

¨

asentationen. Bachelor Thesis,

University of Koblenz–Landau.

Galitz, W. O. (2007). The Essential Guide to User Inter-

face Design: An Introduction to GUI Design Princi-

ples and Techniques. John Wiley & Sons, 3rd edition.

Ivory, M. Y., Mankoff, J., and Le, A. (2003). Using auto-

mated tools to improve web site usage by users with

diverse abilities. Human-Computer Interaction Insti-

tute, page 117.

Kim, W. C. and Foley, J. D. (1993). Providing high-level

control and expert assistance in the user interface pre-

sentation design. In Proceedings of the INTERACT’93

and CHI’93 Conference on Human Factors in Com-

puting Systems, pages 430–437. ACM.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus

or minus two: some limits on our capacity for pro-

cessing information. Psychological review, 63(2):81–

97. Reprinted in Psychological review (1994),

101(2):343.

Montero, F., Vanderdonckt, J., and Lozano, M. (2005).

Quality models for automated evaluation of web sites

usability and accessibility. In International COST294

workshop on User Interface Quality Models (UIQM

2005) in Conjunction with INTERACT.

Nagy, Z. (2013). Improved speed on intelligent web sites.

Recent Advances in Computer Science, Rhodes Island,

Greece, pages 215–220.

Schildt, T. and K

¨

ursteiner, P. (2006). 100 Tipps und Tricks

f

¨

ur Overhead- und Beamerpr

¨

asentationen. Beltz Ver-

lag, 2.

¨

uberarbeitete und erweiterte Aufl. edition.

Shneiderman, B. and Plaisant, C. (2004). Designing

the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-

Computer Interaction. Addison Wesley, 4th edition.

Tobar, L. M., Andr

´

es, P. M. L., and Lapena, E. L. (2008).

Weba: A tool for the assistance in design and evalua-

tion of websites. J. UCS, 14(9):1496–1512.

Wertheimer, M. (2012). On Perceived Motion and Figural

Organization. The MIT Press.

Williams, R. (2015). The Non-Designer’s Design Book.

Peachpit Press, 4th edition.

Windrum, P. (2004). Leveraging technological externali-

ties in complex technologies: Microsoft’s exploitation

of standards in the browser wars. Research Policy,

33(3):385–394.

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

458