Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

Venkatapathy Subramanian

1,2

and Antonia Bertolino

2

1

GSSI, L’Aquila, Italy

2

CNR-ISTI, Pisa, Italy

Keywords:

Business Process, Complex Event Processor, Monitoring, Technology-enhanced Learning, XML.

Abstract:

In modern society the employees of complex organizations are under pressure to constantly improve their

knowledge and skills. Novel approaches and tools to support effective and efficient workplace learning in

collaborative and engaging ways are needed. On the other hand, Business Process Management (BPM) is

more and more employed to support and manage the complex processes carried out within organizations.

BPM can be used as well to guide workplace learning, with the advantage of naturally aligning training

tasks to real tasks. We introduce a specification of learning path that maps BPM tasks and activities into

sequences of learning tasks. Our learning path specification can thus be used to both drive learning sessions

carried out by simulation, and to inform a monitor that can assess learner’s progress. The goal is to combine

work and learning in natural and effective way and use available business monitoring techniques to monitor

the learning progress of the learners. In the paper we describe our specification, the e-learning platform

under development, and the approach to derive monitoring rules. The approach is illustrated through a simple

motivational example.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent times, the penetration of Information and

Communication Technology (ICT) in business orga-

nizations is deep and pervasive: it can be confidently

stated that ICT supports every aspect of the func-

tioning of modern organizations. As the adoption of

ICT increases, the interaction between actual phys-

ical business transactions and software technologies

become heavily intertwined and inter-dependent.

Several methodologies have been proposed to

make the integration of ICT and work procedures eas-

ier and more efficient. One such methodology is Busi-

ness Process Management (BPM) discipline (Jeston

and Nelis, 2014), which helps the organizations to

structure their business functions as a series of pro-

cesses. BPM has matured in the last couple of decades

and has penetrated many large scale organizations in

their design of business processes as well as of the re-

lated software applications needed to execute the pro-

cesses. Systems that are developed using BPM tech-

niques are referred to as Business Process Manage-

ment Systems (BPMS).

As the business environments become more or-

ganized and efficient due to the implementation of

such methodologies, the employees of the organiza-

tion are under pressure to constantly improve their

performance in carrying out the business processes

that they are involved in. Employees are expected to

continuously gain knowledge and increase their skills:

learning is no longer confined within formal courses

in school or University, but happens more and more

as a continuous and lifelong process.

Indeed, advanced countries see investing in em-

ployee education and qualification as a necessary con-

dition to overcome economic crisis and support inno-

vation. Workplaces are now considered as learning

environments that focus on the “interaction between

the affordances and constraints of the social setting,

on the one hand, and the agency and biography of the

individual participant, on the other”. (Billett, 2004)

Hence the need arises for putting in place means to

support workplace learning, as successful individual

learning becomes an important parameter for the suc-

cessful functioning of an organization. In recent years

many training and e-learning methods and frame-

works have been developed to help the employees

learn about the business activities they are involved

with. However state-of-art training and e-learning

sessions are not as successful as aimed because:

• often the training session implies that workers

need to devote extra-work time that is demanding

and exhausting

62

Subramanian, V. and Bertolino, A.

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0005845300620072

In Proceedings of the International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn (AMARETTO 2016), pages 62-72

ISBN: 978-989-758-166-3

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

• learning curve for the training session itself is

steep and apart from their business activities and

hence workers are reluctant to take up the task

• setting up a learning environment similar to the

working environment is very difficult for the com-

pany and usually costly and so workplace training

becomes difficult for the company to setup

Companies look for alternative approaches to train

the employees that can address the above issues. In

our view the requirements for successful workplace

learning should include:

• capability to simulate the actual working environ-

ment for the employees

• efficient and cost-effective set up of the training

environment

• capability to track and customize learning tasks

according to the profile of the employees

Given this context, we propose BPMS as a tool

that organizations can use for knowledge manage-

ment and workplace learning. This idea is at the core

of the ongoing Learn PAd European Project, which is

developing a new approach and a platform to learn-

ing at work (Learn PAd, 2015). The project aims at

exploiting Business Process models based content for

guided, personalized and collaborative learning ses-

sions at work. The proposed approach leverages upon

BPMS features such as collaborative execution be-

tween different users, web-service integration, pro-

cess execution, etc. More precisely, the platform sup-

ports different types of approaches, including infor-

mative learning approach based on enriched Business

Process models, and a procedural learning approach

based on simulation and monitoring.

However BPM is not originally conceived for

learning purposes. Therefore, in the Learn PAd

project we are working at enriching the processes

specification with meta-models related to learning

content and training approaches, and at enabling the

platform to support learning sessions.

As defined in (Janssen et al., 2008a), a sequence

of activities and learning objectives customized to the

needs and competencies of a learner is called a learn-

ing path. In this work we focus on the specification of

a learning path over a BPMS-based Learning System

– we call it BPMLS – and more specifically on how to

enable such a system with means for monitoring and

assessing the learning activities.

Model-based monitoring is traditionally used for

on-line validation of systems behaviour; here we pro-

pose to employ monitoring of our learning path model

during a learning session, with the purpose to inform

both learners and trainers about the progress in the

learning activities.

Since the mentioned Learn PAd project focuses on

the Public Administration (PA) domain, to illustrate

our approach, we use throughout the paper an exam-

ple that represents a simplified process of a PA office,

a Passport office.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. After

introducing some background information (Section 2)

and the motivating example (Section 3), in Section 4

we present our meta-model of a learning path mapped

to BPM models. Then in Section 5 we describe a

model transformation techniques used for monitoring

of learning activities. In Section 6 we describe a pro-

totype and in Section 7 we walk-through our moti-

vational example to show how the approach is used.

Related work and Conclusions sections complete the

paper.

2 BACKGROUND

This section will provide an overview of background

concepts and technologies that are at basis of our

work. In particular, our learning path specification

and monitoring uses and combines concepts and def-

initions related to:

• Business Process Management discipline;

• Business Activity Monitoring systems;

• Workplace Learning approaches;

• Learning Path specification.

We already introduced informally Business Pro-

cess Management (BPM) in the Introduction. More

formally, we adopt here van der Aalst and coauthors

operational definition of BPM (van der Aalst et al.,

2003) as a discipline supporting business processes

using methods, techniques, and software to design,

enact, control, and analyze operational processes in-

volving humans, organizations, applications, docu-

ments and other sources of information.

BPM spans over a complex life-cycle including

stages of design, configuration, enactment and diag-

nosis (van der Aalst et al., 2003) . A Business Process

Management System (BPMS) is a suite of software

tools that leverage BPM concepts and covers some of

the important components of the BPM life-cycle. Us-

ing a BPMS, process models are automated as work-

flow models that are then executed in a process en-

gine. (Van Der Aalst and Van Hee, 2004)

Business Process Management Notation 2.0

(OMG: BPMN, 2011) (in the following referred to

simply as BPMN) provides a standardized graphical

notation for modeling executable business processes

in a workflow. A workflow contains a sequence of

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

63

business activities that may refer to the work of a per-

son, group, or any business applications.

BPMS provide tools for: i. Process modeling, ii.

Process Execution, and iii. Business Activity Mon-

itoring (Van Der Aalst et al., 2003), among other

things. In particular, Business Activity Monitor-

ing (BAM) software can provide real-time access to

critical business performance indicators for business

activities executed by BPMS. BAM software appli-

cations use Complex Event Processing (CEP) tech-

niques (Buchmann and Koldehofe, 2009), to process

simple software-level events and derive higher level

business events. CEP systems are advanced moni-

toring systems capable to combine data coming from

multiple sources so to infer complex events that sug-

gest more complicated circumstances. In particular,

BAM collects raw data of interest during the run-

time business process execution. These collected data

are then analyzed by CEP and correlated to Key Per-

formance Indicators (KPIs) and Goals defined for

the process models. (Calabro et al., 2015; Koetter

and Kochanowski, 2012) Key Performance Indicators

consist of performance metrics that can be used to

measure those aspects of organizational performance

that are most crucial for success of the organization.

(Parmenter, 2015)

By adopting a model-driven approach, BPMS can

be adopted for design of platforms that can both in-

form and mimic business scenarios for adult learn-

ing. In fact, when the modeled business process re-

produces operational process in the offices, such plat-

forms can provide opportunities for the employees

to acquire knowledge while actually doing the activ-

ity, or in simulation. This kind of learning is called

as workplace learning (Billett, 2001). Workplace

learning emphasizes participatory business practices

for individual and collaborative knowledge-gain.

Within the learning context, Learning path is de-

scribed as the chosen route, taken by a learner through

a range of learning activities, which allows them to

build knowledge progressively (Clement, 2000). It

can be used to formally describe learning scenar-

ios (Janssen et al., 2008a). A learning path includes

a learning flow that defines an orchestration detail be-

tween a set of learning activities. (Mari

˜

no et al., 2007)

Learning path specification should also define learn-

ing objectives or outcomes.

Several platform-independent Educational Model-

ing Languages have been proposed to describe learn-

ing paths. The IMS Global Consortium released

the IMS-Learning Design specification that allows

for defining the learning path as a Unit of Learning

(UOL) (IMS Global, 2003). In (Janssen et al., 2008a),

Janssen and coauthors have then provided a generic

learning-path model that is mapped to IMS-LD.

The aim of this paper is to introduce a learning

path specification that can be integrated to BPMS for

workplace learning, and can be monitored using BAM

systems. Our specification draws together the key

concepts and definitions from Business Process Man-

agement discipline and from Workplace Learning ap-

proaches mentioned above. In future we also plan to

evaluate the effectiveness of our Learning Path model

through various empirical studies.

3 MOTIVATIONAL EXAMPLE

This paper is both inspired by and is part of the ongo-

ing Learn PAd Project. We focus on procedural learn-

ing approach of learning by doing, whereby a civil

servant can use the platform to learn about the tasks

related to relevant business processes by performing

a simulation of the activities. The scope of this paper

includes the specification of learning path for work-

place learning and methods to monitor and assess

those learning paths during simulation. Though simu-

lation is part of the Learn PAd platform, its implemen-

tation is out of scope of this paper. We refer to Learn

PAd for details about the simulation component.

To illustrate our approach we introduce as an ex-

ample the case of a Passport office that accepts and

approves passport applications for citizens. Figure 1

shows a BP model that represents a simplified func-

tioning of this office. As shown, accepting a pass-

port application and issuing the passport is a collab-

orative activity involving two actors, namely a clerk

and a passport granting officer. First, the clerk en-

ter details of the passport applicant in a passport ap-

plication management portal. Next step involves a

complex process (abstracted in this example) where

the passport granting officer will check the applicant’s

background record to verify if he/she is eligible for a

passport. In the next step, the officer will be able to

view the status of the application and based on the re-

sults from the background evaluation process can ap-

prove, withhold or reject the application. The verifica-

tion may of course involve other public administrators

and automated services, but here it will abstracted out

as one single step. After verification, if the applica-

tion needs further evaluation (which is dependent on

the outcome of the previous step), the granting officer

may have to withhold the application for further eval-

uation or can reject the application altogether. Else,

he/she will grant the passport for the applicant and

the process stops here.

In this paper we will be using the above example

to demonstrate how learning paths are designed, exe-

AMARETTO 2016 - International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn

64

Figure 1: Example Process: Passport Office.

cuted and monitored.

Our goal is to provide learning path for the above

process that can be executed and monitored in the

framework that we will define in the later sections.

Different learning paths can be defined to reflect the

proficiency expected from the employees of the of-

fice. They may also be based on organizational pol-

icy. For example, since passport issuing is a security-

sensitive process, the learning path might want to en-

sure that all procedures are followed without any er-

rors during the learning process. The office policy

might also require that the passport be issued within a

predefined time limit. We will show in the following

how such conditions can be modeled and enforced in

learning design using our learning path specification

and monitoring approach.

4 LEARNING PATH

META-MODEL

A learning path specification (IMS Global, 2003;

Janssen et al., 2008a) must identify both the sequence

of activities and the related learning objectives reflect-

ing the specific context and tailored to the learner’s

competences.

When it comes to defining learning paths for

knowledge based on business process models, the

specification of the learning flow and the learning ob-

jectives must then comply to the following key re-

quirements:

• Learning flows for business process models have

to be represented by their workflow structure. In

other terms, what an employee learns in relation

to a business process should conform to the se-

quencing of rules established by the business pro-

cess model.

• Learning objectives for business process models

should be correlated to Key Performance Indi-

cators (KPIs) of business activities that form the

learning path.

Our learning path specification is conceived to ad-

dress the above requirements. In fact, the specifica-

tion we introduce here maps KPIs of business pro-

cesses to learning objectives of the learning path.

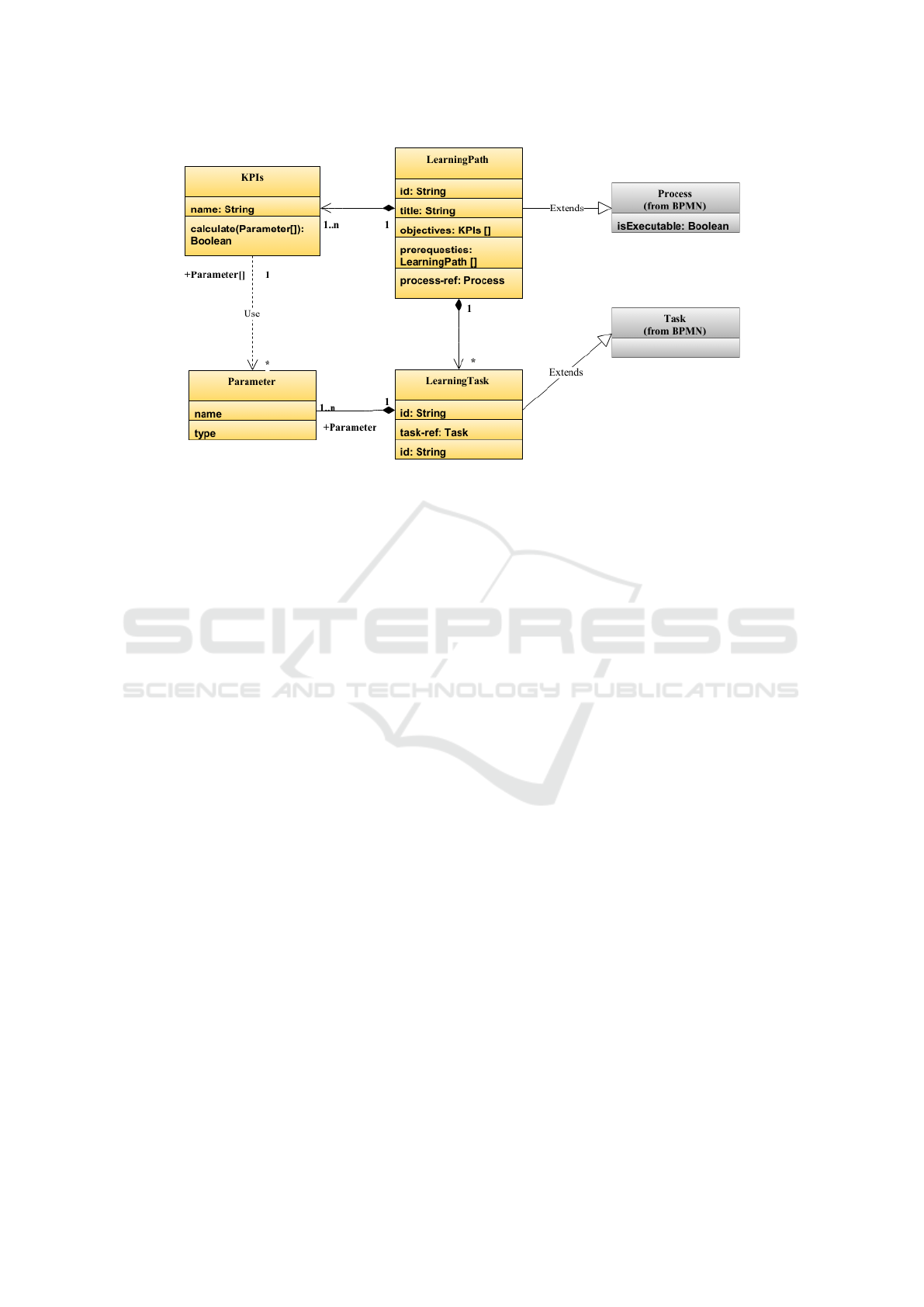

Figure 2 represents the meta-model of our learning

path specification. This specification allows us to

define a learning path on top of a BPMN specifica-

tion. Precisely, we extend the BPMN meta-model

with the introduction of classes and attributes related

to a learning path. In the figure, classes with grey

background are related to the BPMN model. Classes

with yellow background (those that we introduce) are

related to the learning path specification.

LearningPath class is extended from Process

class, that is used to formally represent the business

process model within BPMN. (Process class is ex-

plained in detail in the BPMN specification to which

we refer for further details). Process instances can be

extended with LearningPath only when the attribute

isExecutable is set to true. This is to ensure that learn-

ing paths are defined only for deployable BPMN pro-

cess models, given that we intended to use the busi-

ness process model for simulation.

An instance of Process (with isExecutable set to

true) can be used to initialize one or more instances

of LearningPath. During the initialization, values of

Process attributes are copied to their corresponding

attributes in the LearningPath instance, and attribute

process-ref of LearningPath is used to refer to the

Process instance. A instance of LearningPath can

be executed in the BPMLS through model transfor-

mation (which we will explain in Section 5) to Pro-

cess.

Many LearningPaths can be created from one in-

stance of Process, and each instance of Learning-

Path represents one learning session. The Id attribute

of class LearningPath is used to uniquely identify

a learning instance. The prerequisites attribute is an

array of type LearningPath and points to a list of

LearningPath instances that needs to be executed be-

fore the current LearningPath can be in turn exe-

cuted. Attribute objectives is used to set the learning

objectives for the learning path and is an array of type

KPI. We will describe the class KPI below.

Process and LearningPath may contain one or

more instances of Task. A Task class represents an

atomic activity within Process flow. For every Task,

a LearningTask instance maybe created. Learning-

Task inherits all attributes from its parent Task in-

stance, and has an attribute task-ref which is a pointer

to its parent Task. Id is used to identify the learning

task. resource is used to restrict the learning activities

to a group of users and is derived from ResourceRole

class of BPMN specification.

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

65

Figure 2: Learning path specification for business process model.

LearningTask contains one or more instances of

Parameter class. Parameter class captures values

that are used for monitoring purposes. Parameter

class contains attributes name and value. name is

used to uniquely identify the instance of Parameter

and value is set during the learning session based on

the output from LearningTask.

One or more instances of Parameter can be used

within KPI calculate() function. The calculate()

function returns a boolean value and is used to check

if a given Key Performance Indicator for the business

scenario is fulfilled. As mentioned above, an array

of KPI can be used within the attribute objectives of

LearningPath to define its learning goals.

In this section we have provided a learning path

specification for business process models. In the next

section we will provide a model transformation tech-

nique to derive business process models and CEP

queries that can then be executed within BPMS and

BAM respectively.

5 MONITORING OF LEARNING

PATH MODELS

The Learning Path meta-model defined in Section 4

can be used to define many learning related properties

on top of business process models. Several BPMS ex-

ist that can understand BPMN models, and hence it is

more convenient to reuse existing BPMN compliant

execution platforms to design BPMLS learning plat-

forms. We believe that a BPMS can be extended into

a BPMLS platform if the following three functionali-

ties can be included:

• A model to Specify Learning Path on Top of

Business Process Models: This is what we pro-

vide in Section 4.

• A platform to Design Learning Models: It can

be a tool developed on top of BPMS modeling

tools. This work is currently in progress within

the Learn PAd Project, and we are not covering

this in this paper.

• Methods to Monitor and Assess the Learning

Progress of a User: In this section we will focus

on this latter functionality.

BPM methodology already includes monitoring

capabilities within its life-cycle. A BAM software

can provide real-time informations about busi-

ness process executed using BPMS. An effective

workplace learning platform should also be able to

monitor and assess a learner’s progress. A BPMLS

can extend the functionalities of BAM for monitoring

and assessment of the learner.

Using the learning path specification previously

introduced, we developed a model transformation

technique to derive business process models and CEP

queries that can then be executed within BPMS and

BAM respectively.

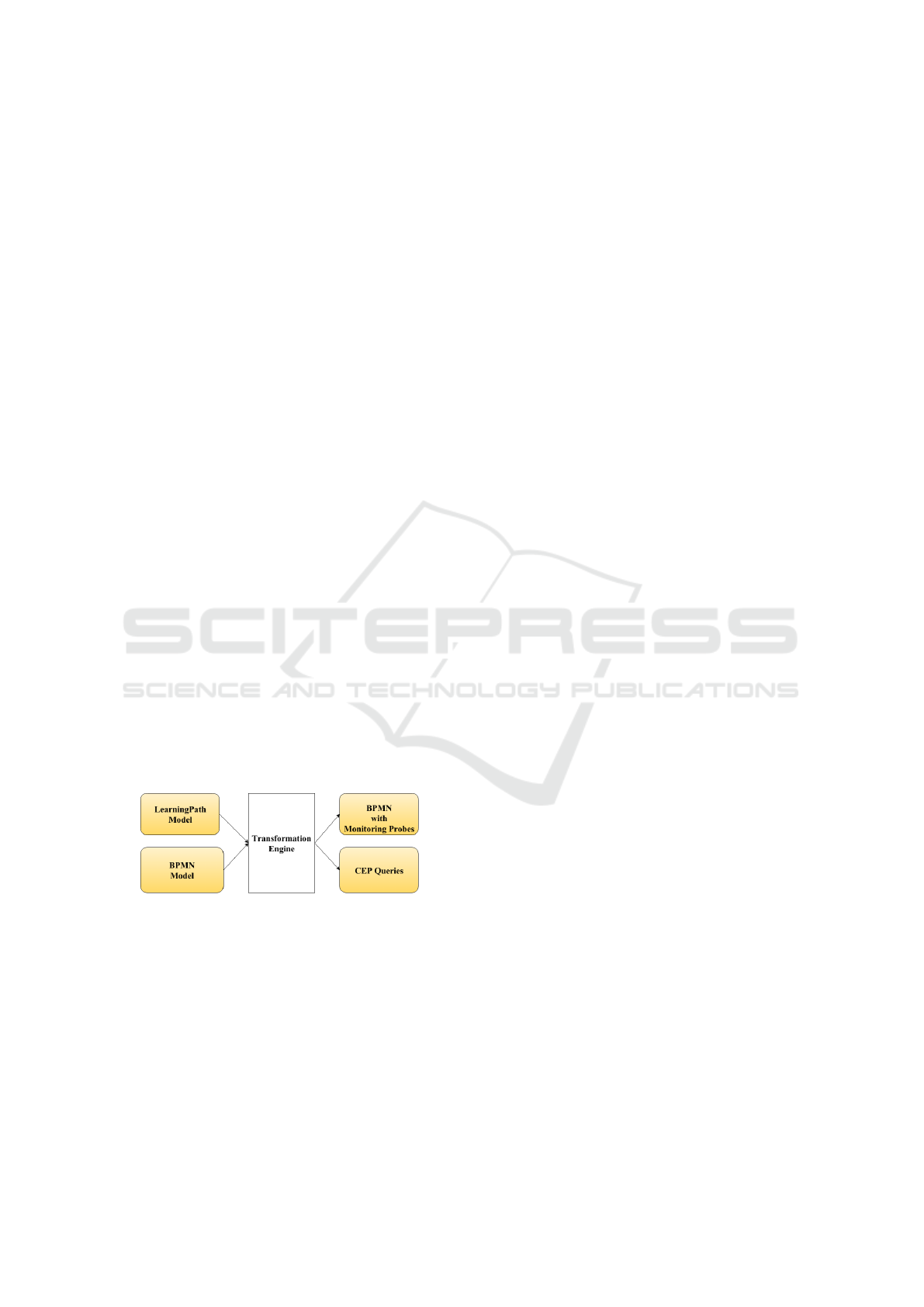

An overview of a unidirectional model transfor-

mation is represented in Figure 3. A standard BPMS

engine can be used to deploy process definition de-

fined using XML representation of BPMN. On the

other hand, CEP queries can be defined within a

BAM software either as SQL-like queries or a set of

rules depending on CEP engine specification. Since

monitoring is out of scope of BPMN specification,

AMARETTO 2016 - International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn

66

the BPMN meta-model provides a generic Monitor-

ing meta-model that allows defining attributes related

to monitoring. It leverages the BPMN extensibility

mechanism. The actual definition of monitoring at-

tributes is not provided in BPMN specification and

BPMN 2.0 implementations define their own set of at-

tributes and their intended semantics. (OMG: BPMN,

2011)

The goal of our transformation technique is to ac-

cept both the learning path model as well as its refer-

enced business process model and provide two forms

of outputs that can be executed within BPMS and

BAM respectively. The transformation involves two

steps:

1. Creation of BP models with monitoring probes:

In this step, for each of the LearningTask a trans-

formation is applied to its corresponding Task of

the business process model. The relationship be-

tween LearningTask and Task is identified using

the attribute task-ref of LearningTask. The trans-

formation involves addition of monitoring probes

that sends values defined by Parameter of Learn-

ingTask.

2. Creation of CEP Queries: Since a learning path

specification is an atomic learning process and

corresponds to one process instance within BPMS

(as described in Section 4), a single complex-

event unit is defined for one LearningPath.

BPMS engine takes values of Parameter from

its system and the value is sent to a CEP engine

through the monitoring probes. The CEP engine

executes the functions defined in KPI class, which

are related to learningobjective of a Learning-

Task

Figure 3: Overview of Model Transformation.

6 PROTOTYPE

A prototype was developed to evaluate the learn-

ing path model transformation and assessment tech-

niques. It is conceived such that an employee who

needs to learn about a business process can log in to

the system and will find an environment mimicking

the real business process for learning purposes.

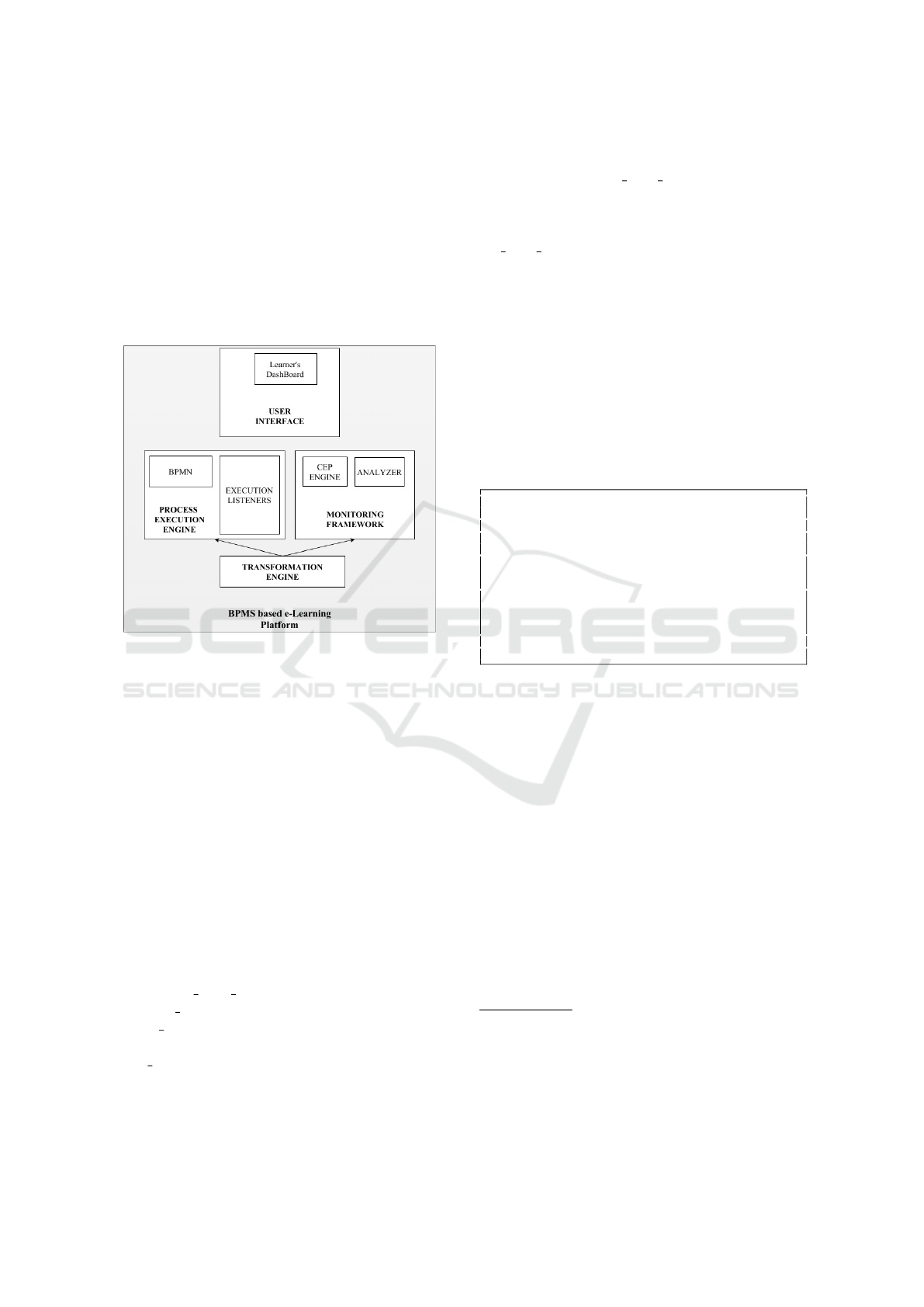

Figure 4 represents the overall framework of our

platform. The framework consists of four main com-

ponents:

i. Transformation Engine to transform learning path

model into BPMN model and CEP queries respec-

tively

ii. Process Execution Engine to executed the trans-

formed BPMN model

iii. Monitoring Framework to monitor and assess a

learning path

iv. A User Interface for displaying learning progress

to the users.

The transformation engine was developed based

on the description provided in Section 5. Currently

the transformation is performed in a semi-automated

way, where the BPMN models are generated automat-

ically and later manually updated with the required

monitoring probes. CEP queries are also generated

manually (explained in the later part of this section).

We are in the process of automating the transforma-

tion technique.

For the Process Execution Engine we use Apache

Activiti, an open-source Java-Based BPM Platform.

(Rademakers, 2012)

For monitoring we use Drools Fusion (Drools Fu-

sion 6.0.3, 2015) based CEP engine. Drools fusion

provides mechanism to declare rules that can be used

to read a stream of events and infer a complex event

based on the conditions defined in the rule. Apache

Explorer is used as the user interface component and

has been extended to display the learning progress to

the users.

Apache Activiti provides with mechanism to ex-

ecute external Java Code, called execution listeners,

when certain events occur during process execution.

The events can be defined on the level of process, ac-

tivity or transition levels. The execution listeners are

useful to capture process-level variables that are gen-

erated during execution and send them (say as web

service calls or REST calls) to a monitoring frame-

work.

During the model transformation from learning

path model to business process model, execution lis-

teners are created for every Task (referred as Activity

in Apache Activiti Parlance) that has LearningTasks

related to it. The execution listener contains methods

to read Parameters values and send them to the mon-

itoring framework.

A overview of the relation between objects of

different components such as learning path model,

BPMN model, events and Drools Fusion CEP rules

is provided in Figure 5. A LearningPath object

has LearningTasks that contains Parameters. Af-

ter model transformation, every LearningPath has a

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

67

Process. Activity corresponding to LearningTasks

has execution listeners that collect Parameters val-

ues. A Process triggers ’start’ and ’end’ events

whereas Activity triggers only ’end’ event. The ex-

ecution listeners send the values of Parameters as

and when the events are triggers. CEP rules receive

and monitor the events. CEP rules element has func-

tions to calculate KPIs based on the received events,

whereby the function to calculate the KPI is derived

from KPI calculate function from the learning model.

Figure 4: Framework for Learning Path Execution and

Monitoring.

7 APPLICATION EXAMPLE

With reference to the motivational example intro-

duced in Section 3, an instance of Learning Path

specification is provided in Figure 6. It contains

three LearningTasks attached to LearningPath that

correspond to each of the tasks presented in the

example, namely: ‘Accept Application’, ‘Check

Application’, and ‘Approve Application’. Instances

‘Accept Application’ and ‘Check Applications’ have

one Parameters each, while ‘Approve Application’

has two Parameters. There is one KPI that is

associated with Objectives of LearningPath, and

the calculate function contains the following function:

Beginner Time SLA =

(Approve Application.timestamp −

Accept Application.timestamp) < $expectedSLA

&&

valid

entry = true

&expectedSLA is a variable that can be defined by

an administrator to denote the completion time of the

process. It can be noted that the KPI instance access

the values of the Parameter class.

The KPI Beginner Time SLA is defined as dif-

ference between the time when application was ac-

cepted and approved and is converted to an integer

indicating the difference. It will return true if Begin-

ner Time SLA is less than expectedSLA, or false oth-

erwise. This goal will be used to check if during the

simulation in learning the process is completed within

expected deadline and defines the learning objective

of the Beginner LearningPath.

During model transformation, the Tasks in Busi-

ness Process models is added with appropriate execu-

tion listeners that will be used as monitoring probes to

send the Parameter values to the CEP engine. For ex-

ample, Listing 1 below provides the XML definition

for the activity ‘Accept Application’ with execution

listeners.

Listing 1: BPMN specification with execution listeners.

1 <u s e r T a s k i d =” a c c e p t a p p l i c a t i o n ” name =” Accept

A p p l i c a t i o n ” a c t i v i t i : a s s i g n e e =” c l e r k”>

2 <e x t e n s i o n E l e m e n t s >

3 < a c t i v i t i : f o r m P r o p e r t y i d =”name ” name =”Name”

t y p e =” s t r i n g ”></ a c t i v i t i : f o r m P r o p e r t y>

4 < a c t i v i t i : f o r m P r o p e r t y i d =” i d ” name=”

I d e n t i f i c a t i o n ” t y p e =” s t r i n g ”></

a c t i v i t i : f o r m P r o p e r t y >

5 < a c t i v i t i : e x e c u t i o n L i s t e n e r c l a s s =” o r g .

a c t i v i t i . m o n i t o r .

A c c e p t A p p l i c a t i o n E v e n t L s t ” e v e n t =” end ”

/>

6 </ e x t e n s i o n E l e m e n t s >

7 </u s e r T a s k>

During execution, when the ‘Accept Application’

task is ended, the process execution will call the lis-

tener AcceptApplicationEventLst.

1

Similarly, CEP rules are created for each of the

learning path model, and are deployed within the

Drools Fusion CEP engine. Listing 2 provides a

skeleton rule file for the beginner learning path. At

time of writing, rules are created manually and au-

tomation is ongoing.

A sample application was developed based on

the prototype defined above. As mentioned above,

Apache Activiti Explorer was used to design, and ex-

ecute the process models. Learning path model and

its corresponding business process models, CEP rules

were created separately. The explorer interface was

modified to detect and display the learning progress

to the users. Figure 7 provides a screenshot in which

the ‘Approve Application’ task is executed. Figure 8

1

In technical terms, AcceptApplicationEventLst in-

stantiates a Plain Old Java Object (POJO) AcceptAppli-

cationEvent and sets a timestamp property to indicate the

time when the ’Accept Application’ event is finished. Like-

wise the model transformation creates execution listeners

for each of the LearningTasks provided in the learning path

model.

AMARETTO 2016 - International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn

68

Figure 5: Overview of relation between objects of different components.

provides a screenshot of a simplified webpage where

the progress of the learner is registered. (note that

the screen contains references to another learning path

called ‘Advanced’. This is to showcase that many

learning path models can be created.)

Listing 2: CEP rule for a learning path model.

1 r u l e ” B e g i n n er − L e a r n i n g P a t h M o n i t o r i n g ”

2

3 when

4 # c o n d i t i o n s

5 # c a l c u l a t e KPI f u n c t i o n s a s d e f i n e d i n t h e l e a r n i n g

p a t h mod el

6

7 t h e n

8 # up d a t e t h e l e a r n i n g p a t h a s c o m p l e t e d

8 RELATED WORK

Different approaches have been considered for as-

sistance of lifelong learning for individuals such as

the European Union project TENCompetence (Koper

and Specht, 2006) which developed a framework

within which daily competence development activi-

ties can be carried out. Within the broad category of

workplace learning, some research community have

tried to use BPM concepts for the management of

collaborative learning processes. Marino and coau-

thors (Mari

˜

no et al., 2007) proposed a method to

transform learning design models defined using IMS-

LD specification to business process execution model

called XML Process Definition Language. The goal

was to use IMS-LD for defining a learning design

and use business process engine as a delivery plat-

form for the learning designs. In (Karampiperis and

Sampson, 2007), Karampiperis and coauthors exam-

ine using of BPMN as a common representation no-

tation for learning flows modeled using Business Pro-

cess Execution Language (BPEL) and present an al-

gorithm for transforming BPEL Workflows to IMS-

LD learning flows.

Vantroys and Peter (Vantroys and Peter, 2003) pre-

sented Cooperative Open Workflow (COW), a flexible

workflow engine that can be used to transform IMS-

LD into XPDL designs to enact the learning models

in the platform. Another e-learning platform called

Flex-el (Lin et al., 2002) has also been built on top

of workflow technology. It provides a unique envi-

ronment for teachers to design and develop process-

centric courses and to monitor student progress.

Above discussed methodologies and platforms fo-

cus on using BPM techniques and technologies for

designing learning specifications for academic sce-

narios and do not focus on workplace learning.

Regarding learning path specification, Janssen and

coauthors proposed learning path information model

that can represent a formal learning path model

(Janssen et al., 2008b). However, the specification

is generic and does not address the requirements of

workplace learning based on BPM.

As far as we know none of the existing works fo-

cuses on using BAM for workplace learning moni-

toring. In their work, Adesina and coauthors focus

on visually tracking the learning progresses of a co-

hort of students in a Virtual Learning Process Envi-

ronment (VLPE) based on the Business Process Man-

agement (BPM) conceptual framework (Adesina and

Molloy, 2012). Their work focuses on learning speci-

fications for academic scenarios and does not focus on

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

69

Figure 6: An instance of Learning Path model.

Figure 7: Execution of Approve Application task.

AMARETTO 2016 - International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn

70

Figure 8: A Simple Screen to display learning progress.

workplace learning. Also their tracking of the learn-

ing progress does not leverage BAM systems.

Our work defines a precise specification that can

be used for defining learning path for business process

models, as well as transformation techniques for us-

ing standard business activity monitoring techniques

to monitor learning progress of an employee.

9 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

Our research aims at exploiting the potential of BPM

to support effective and realistic workplace learning

activities. BPMS solutions used at work are very

powerful and widely used, but they are not conceived

for learning purposes. To the best of our knowledge

there is no existing proposal to adapt BPMS for learn-

ing needs by extending the notation to define a learn-

ing path.

This work in particular aims at filling the gap be-

tween BPM used for work, and workplace learning

needs by extending BP models with features to spec-

ify learning flow and learning objectives. This stays

within the context of the European Learn PAd project,

that aims at exploiting enriched BPMN models for

deriving both recommender systems and simulation

sessions used expressly for learning the modeled se-

quence of tasks by workers.

We introduced a preliminary specification of

learning path that extends the standard BPMN speci-

fication by including learning relevant concepts. We

then proceeded to provide a model transformation

technique from learning path specification to queries

that can be directly sent to a CEP to monitor and as-

sess learner’s progress.

We are currently refining platform implementa-

tion, and testing it on several scenarios defined within

the Learn PAd project. In particular, future work will

focus on methods to automate the generation of CEP

queries for learning path monitoring. In future we are

also looking at integrating the simulation environment

of Learn PAd platform thereby making it possible to

define learning path models for individual users such

that the collaborative activity of other users can be

simulated using the system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been partially supported from the

European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme

[FP7/2007-2013] under Grant Agreement N. 619583

(Project Learn PAd - Model Based Social Learning

for Public Administrations).

Monitoring of Learning Path for Business Process Models

71

REFERENCES

Adesina, A. and Molloy, D. (2012). Virtual learning pro-

cess environment: Cohort analytics for learning and

learning processes. World Academy of Science, Engi-

neering and Technology, 65.

Billett, S. (2001). Learning in the Workplace: Strategies for

Effective Practice. ERIC.

Billett, S. (2004). Workplace participatory practices: Con-

ceptualising workplaces as learning environments.

Journal of workplace learning, 16(6):312–324.

Buchmann, A. and Koldehofe, B. (2009). Complex event

processing. it-Information Technology Methoden und

innovative Anwendungen der Informatik und Informa-

tionstechnik, 51(5):241–242.

Calabro, A., Lonetti, F., and Marchetti, E. (2015). Mon-

itoring of business process execution based on per-

formance indicators. In Software Engineering and

Advanced Applications (SEAA), 2015 41st Euromicro

Conference on, pages 255–258. IEEE.

Clement, J. (2000). Model based learning as a key research

area for science education. International Journal of

Science Education, 22(9):1041–1053.

Drools Fusion 6.0.3 (2015). Drools Fusion: Complex

Event Processor. http://www.jboss.org/drools/drools-

fusion.html. Last Accessed: 27th November 2015.

IMS Global (2003). IMS- Learning Design.

http://www.imsglobal.org/learningdesign/index.html.

Last Accessed: 27 November 2015.

Janssen, J., Berlanga, A., Vogten, H., and Koper, R.

(2008a). Towards a learning path specification. Inter-

national journal of continuing engineering education

and life long learning, 18(1):77–97.

Janssen, J., Hermans, H., Berlanga, A. J., and Koper, R.

(2008b). Learning path information model. Retrieved

November, 9:2008.

Jeston, J. and Nelis, J. (2014). Business process manage-

ment. Routledge.

Karampiperis, P. and Sampson, D. (2007). Towards a com-

mon graphical language for learning flows: Trans-

forming bpel to ims learning design level a represen-

tations. In Advanced Learning Technologies, 2007.

ICALT 2007. Seventh IEEE International Conference

on, pages 798–800. IEEE.

Koetter, F. and Kochanowski, M. (2012). Goal-oriented

model-driven business process monitoring using pro-

goalml. In Business Information Systems, pages 72–

83. Springer.

Koper, R. and Specht, M. (2006). Ten-competence: Life-

long competence development and learning.

Learn PAd (2015). Learn PAd - Model-Based

Social Learning for Public Administrations.

http://www.learnpad.eu. Last Accessed: 27 November

2015.

Lin, J., Ho, C., Sadiq, W., and Orlowska, M. E. (2002).

Using workflow technology to manage flexible e-

learning services. Journal of Educational Technology

& Society, 5(4):116–123.

Mari

˜

no, O., Casallas, R., Villalobos, J., Correal, D., and

Contamines, J. (2007). Bridging the gap between e-

learning modeling and delivery through the transfor-

mation of learnflows into workflows. In E-Learning

Networked Environments and Architectures, pages

27–59. Springer.

OMG: BPMN (2011). Business Process Modeling Nota-

tions.2.0. http://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0/. Last

Accessed: 27 November 2015.

Parmenter, D. (2015). Key performance indicators: devel-

oping, implementing, and using winning KPIs. John

Wiley & Sons.

Rademakers, T. (2012). Activiti in Action: Executable busi-

ness processes in BPMN 2.0. Manning Publications

Co.

van der Aalst, W., ter Hofstede, A., and Weske, M. (2003).

Business process management: A survey. In van der

Aalst, W. and Weske, M., editors, Business Process

Management, volume 2678 of Lecture Notes in Com-

puter Science, pages 1–12. Springer Berlin Heidel-

berg.

Van Der Aalst, W. and Van Hee, K. M. (2004). Workflow

management: models, methods, and systems. MIT

press.

Van Der Aalst, W. M., Ter Hofstede, A. H., and Weske, M.

(2003). Business process management: A survey. In

Business process management, pages 1–12. Springer.

Vantroys, T. and Peter, Y. (2003). Cow, a flexible platform

for the enactment of learning scenarios. In Group-

ware: Design, Implementation, and Use, pages 168–

182. Springer.

AMARETTO 2016 - International Workshop on domAin specific Model-based AppRoaches to vErificaTion and validaTiOn

72