Are Open News Systems Credible?

An Investigation Into Perceptions of Participatory and Citizen News

Jonathan Scott

1

, David Millard

1

and Pauline Leonard

2

1

Web and Internet Science, School of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K.

2

Sociology, School of Social Science, University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K.

Keywords:

Social Network, Social Media, Credibility, Openness, Audience Participation, Citizen Journalism, Online

Media.

Abstract:

The growth of the web has led to a shift in the news industry and the emergence of novel news services. Due

to the importance of news media in society it is important to understand how these systems work and how they

are perceived. Previous work has ranked news systems in terms of their openness to user contribution, noting

that the most open systems (such as YouTube) are typically not viewed as news systems at all, despite having

most of the same functional characteristics. In this paper we explore whether credibility is an appropriate

characteristic to explain this perception by presenting the results of a survey of 79 people regarding their

credibility assessments of online news websites. We compare this perceived credibility with the openness of

the systems as identified in previous work. Results show that there is a modest but significant correlation

between the openness of a news system and its credibility, and suggest that credibility is an appropriate if

imperfect explanation of the difference in perception of open and closed news systems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade the web has changed the way

that many interact with the news, blurring bound-

aries between production and consumption, and cre-

ating new models of journalism which are described

by terms such as “produsage”, “participatory journal-

ism”, and “civic journalism”. In 2014 it was found

that half of social network users shared news on their

social network accounts, 46% of users discussed news

on these sites, and roughly 10% of users had pub-

lished news videos they made themselves (Mitchell,

2014). Because of the position of the news media in

society it is important to understand how these new

web-based news systems function and how people

perceive and interact with them.

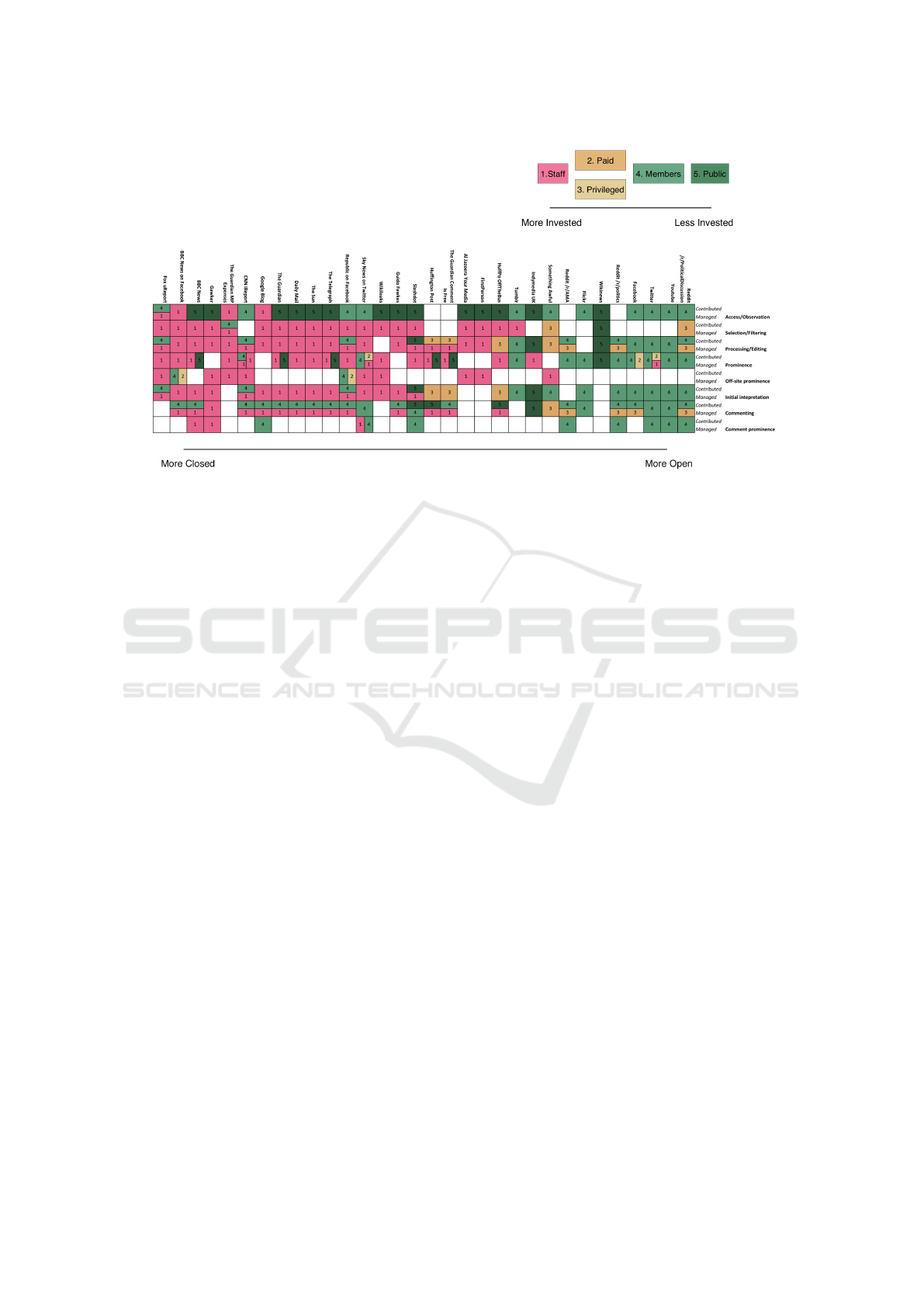

Our previous work has undertaken systematic

analysis of the news processes for a variety of dif-

ferent news systems, and pointed out the confusion

of terms used to describe them (Scott et al., 2015).

This built on previous analyses (particularly that pre-

sented in Domingo et al. 2008), and instead of cate-

gorizing systems into discrete groups, placed them on

a spectrum according to their level of openness. This

produced the spectrum of 32 news systems shown in

Figure 1.

In this work, a difference was identified between

the way closed systems and open systems were per-

ceived (Scott et al., 2015), but this difference was not

elaborate upon. It seems intuitive that the spectrum

ranges from traditional media outlets on the left to

new social media on the right, though this raises the

question as to what measures reflect this difference.

This paper will investigate if this can be explained by

the perceived credibility of the systems.

2 BACKGROUND

Credibility is a measure of how “believable” a piece

of information is (Fogg, 1999), and has been consid-

ered one of the key elements in judging news sys-

tems (Aalberg and Curran, 2011). Common fac-

tors linked to credibility include accuracy, balance,

level of bias, fairness, and honesty (Hellmueller and

Trilling, 2012).

Online news systems bring with them a unique set

of challenges related to assessing credibility. With

the web decreasing the cost of publishing informa-

tion, the gate-keeping role of journalists is being chal-

lenged, making individuals personally responsible for

assessing the credibility of much of the media they

Scott, J., Millard, D. and Leonard, P.

Are Open News Systems Credible? - An Investigation Into Perceptions of Participatory and Citizen News.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2016) - Volume 1, pages 263-270

ISBN: 978-989-758-186-1

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

263

Figure 1: The landscape of citizen participation. (Scott et al., 2015).

consume. There is evidence to suggest that many

people lack the required digital literacy skills to accu-

rately judge the credibility of online news (e.g. Met-

zger et al., 2003, 2010; Flanagin and Metzger, 2000).

Traditionally, three dimensions of credibility are

heavily studied: message credibility, source credibil-

ity, and media credibility (Metzger et al., 2003).

Message credibility includes specific features of

the message content, including information quality;

language intensity; and message discrepancy (Hell-

mueller and Trilling, 2012). As we are interested in

the relative quality of news websites, rather than mes-

sages within a website, message credibility will not be

relevant to our study. However, it has been shown that

the credibility of one piece of content influences the

way credibility judgements are made for other con-

tent on the same page (Thorson et al., 2010). Though

the more closed systems on the spectrum do have con-

tent from multiple authors on a single page, this is far

more common on the more open systems. This may

impact on the credibility of the systems to the right of

the spectrum.

Source credibility examines the personal charac-

teristics of the message source that influence credibil-

ity judgements, including expertise; trustworthiness;

and sociability (Wathen and Burkell, 2002). On the

web, the influence of source credibility is difficult to

measure as the source of a message is often misat-

tributed: to website owners, sponsors, and even to

web designers (Metzger et al., 2003). Many online

news sites have content from multiple sources and the

impact of each individual source on overall credibility

is difficult to extract.

Schweiger (2000) found that news organisations

with credibility in traditional media may have their

web presence judged more credible than those that

lack this traditional media presence. This can be ex-

plained as a feature of Tseng and Foggs “experienced

credibility” (Tseng and Fogg, 1999) and an assump-

tion that the organisation maintains similar editorial

standards on the web as they do in non-web media.

Sundar and Nass (2001) found that the credibility

of what they called the “selecting source” was also

important when judging source credibility. The se-

lecting source is the entity that chose to share the con-

tent rather than the one that initially collected or cre-

ated it. Sundar and Nass found that users viewed in-

formation selected by other users to be more credible

than information selected by an expert, though Sundar

et al. (2007) found that the credibility of the original

source is still important. Schmierbach and Oeldorf-

Hirsch (2012) found that this effect of the selecting

source increasing the credibility of a piece of content

did not apply to content shared on Twitter, and posited

that this may be due to the Twitter platform’s reputa-

tion as a place for “celebrities and shallow posts”.

Media credibility concerns the credibility of a

communications medium. Traditionally, much me-

dia credibility research has concerned the relative

credibility of television news and newspapers, with

newspapers typically being perceived to be less accu-

rate and more biased than television (Metzger et al.,

2003). Reasons for this include that television can

report live breaking news which proscribes author-

ity and importance (Chang and Lemert, 1968), that

television allows consumers to see what is happening

rather than it being described (Carter and Greenberg,

1965; Gaziano and McGrath, 1986), and because TV

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

264

news typically covers fewer stories than newspapers

they are less likely to make mistakes which reduce

confidence (Wilson and Howard, 1978), or to push

dissonant messages which increase the appearance of

bias (Carter and Greenberg, 1965).

Some of these differences between television

news and newspapers are also present when com-

paring newspapers and online news. Online news

is able to react to ongoing events even quicker than

television news, and with the prevalence of camera-

enabled mobile phones and modern web technolo-

gies, online news systems are able to show videos of

events promptly, sometimes even as they are occur-

ring. These features may lead to websites being per-

ceived as more credible than newspapers, but other

factors will lead to the web having less credibility.

These include the fact that on the web there is much

more information, on many more topics, from many

more people and points of view, than there is in news-

papers. This increases the chances of mistakes being

made and of the medium appearing biased.

This means that depending on the weighting at-

tributed to each factor, the web as a whole may be

seen as less credible, equally credible, or more cred-

ible than newspapers. Research is available to sup-

port each of these positions. For example see Johnson

et al. (2007), Flanagin and Metzger (2000), and John-

son and Kaye (1998) which found online informa-

tion to be more credible than offline, Kiousis (2001)

which found online information to be more credible

than television but less credible than newspapers, and

Schweiger (2000) which found online information to

be less credible than both newspapers and television.

Which type of credibility we ought to focus on

is unclear due to the inconsistent use of terms in

the literature. As mentioned by Hellmueller and

Trilling (2012), The Yale Group Communication Re-

search Program defines “sources” as individual per-

sons, institutions or magazines, whereas McCroskey

and Young (1979) defined this as individual com-

municators. The systems on the spectrum could be

classed as source institutions under the Yale Group

definition but would not fit McCroskey and Young’s

definition.

The systems could also be classed as news me-

dia, with the individual contributors acting as sources.

Rather than analysing the credibility of the web as a

whole we would, for example, investigate the credi-

bility of Twitter as a news medium when compared

to Facebook. For our purposes, we will consider the

technical systems to be news media, and will use me-

dia credibility measures to investigate the differences

on each side of the spectrum.

2.1 Spectrum of Credibility

With previous work having built a spectrum of open-

ness of online news media, we will now investigate

available literature on the credibility of specific on-

line news systems to build an idea of how openness

relates to credibility.

For the more-closed systems, Flanagin and Met-

zger (2007) found that traditional online news sources

ranked higher than other news sources in credibility,

and Melican and Dixon (2008), when investigating

credibility and racism in online news, found that non-

traditional internet news sources were perceived as

less credible than all other sources of news. How-

ever, Kim and Johnson (2009) found that politically-

interested South Koreans viewed independent online

news sites as more credible than traditional media

websites.

In the centre of the spectrum, blogs have been

shown in some cases to be rated as trustworthy,

though primarily by people already skeptical of main-

stream media or regular users of blogs, with non-users

holding lower opinions of blogs’ credibility (Johnson

and Kaye, 2009; Choi et al., 2006), but Schmierbach

and Oeldorf-Hirsch (2012) found that overall, blogs

were less credible than mainstream news.

For the more open systems, Schmierbach and

Oeldorf-Hirsch (2012) compared information pre-

sented via a news organisation’s Twitter feed to in-

formation presented directly by the news organisa-

tion, and found that “Twitter is seen as a less credi-

ble source that may or may not present a less credi-

ble message”. Marchionni (2013) explored the con-

versational features and credibility of news on Twit-

ter, Wikinews, and “collaborative news” (Thorson

and Duffy, 2006). They found that their participants

rated collaborative news as more credible than Twit-

ter, which in turn was more credible than Wikinews.

We can see that there is some evidence that more

closed systems tend to be viewed as credible, and

more open systems tend to lack credibility. However,

there is conflicting data, and due to the inconsistencies

in scales used and the differing definitions of ‘credi-

bility’ used (see Hellmueller and Trilling, 2012), we

are not able to draw any overall conclusions regard-

ing the relationship between openness and credibility

from these results. Instead, we will perform our own

study of the perceived credibility of news systems.

2.2 Measuring Credibility

There have been a number of proposed ways of mea-

suring the perceived credibility of a piece of media.

Hellmueller and Trilling (2012) performed a meta-

Are Open News Systems Credible? - An Investigation Into Perceptions of Participatory and Citizen News

265

(a) Unbiased (b) Fair

(c) Tells the whole story (d) Accurate

(e) Trustworthy

Figure 2: Plots of ratings of Meyer’s factors against position on the openness spectrum.

analysis of credibility research between 1951 and

2011, finding inconsistent use of concepts and a “pro-

liferation of questionable items and scales” dominat-

ing credibility research. They found that of the 85

scales they investigated, only 16 replicated previously

used scales. This makes deciding on the scale to use

in this study difficult.

One scale which was used often, though can not

be considered a standard, is that presented by Meyer

(1988). Meyer validated the twelve factors previously

proposed by Gaziano and McGrath (1986) and pro-

duced five factors which represent credibility. These

have been shown to validly and reliably measure cred-

ibility (West, 1994).

In Hellmueller and Trilling’s meta-analysis,

Meyer’s credibility index was the most commonly

used set of factors, being used 6 times to measure me-

dia credibility (out of 29 in total), 3 times for source

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

266

credibility (out of 21), 2 times for message credibility

(out of 8), and 3 times in other studies (out of 10).

In the absence of an accepted standard, this study

will use the Meyer credibility scales, the factors of

which are: Unbiased/Biased, Fair/Unfair, Tells/Does

not tell the whole story, Accurate/Inaccurate, and

Can/Cannot be trusted.

3 METHODOLOGY

In order to measure the relationship between a news

system’s position on the openness spectrum and the

credibility of the systems, we employed a web-based

study. The survey was spread primarily via social

media and participants were prompted to forward the

study to their contacts. This resulted in 79 respon-

dents (73% male, 27% female, age m=30). All re-

spondents were British, the majority (75%) had grad-

uated university, and 56% of respondents were em-

ployed for wages, whereas 30% were students.

The participants were shown a list of news sys-

tems, from which they selected those they were fa-

miliar with. They were then presented with up to ten

randomly ordered news systems with which they have

familiarity. For each system, the participants were

asked to rate the system against each of Meyer’s fac-

tors, to give the reasons for these ratings, and asked

how often they interact with the system.

All systems from the spectrum presented in Scott

et al. (2015) were available for rating. “The Huffing-

ton Post OnTheBus” was renamed to “OnTheBus (by

The Huffington Post)”, “The Guardian MP Expenses”

was renamed to “MP Expenses Investigation (by The

Guardian)”, “The Guardian Comment Is Free” was

renamed to “Comment Is Free (by The Guardian)”,

and “Al Jazeera Your Media” was renamed to “Your

Media (by Al Jazeera)” as it was found during exper-

iment validation that several participants misunder-

stood the question as referring to the parent system

and answered accordingly.

4 RESULTS

Participants submitted ratings for 27 of the 32 systems

presented. For each system this included a rating be-

tween 0 and 4 for each of the five factors, and a rating

between 0 and 4 representing the level of interaction

with the system (0 = never, 4 = very often). Some

participants also provided reasons for their ratings.

Several systems received no ratings at all: OffThe-

Bus (by Huffington Post), Fox uReport, CNN iReport,

MSNBC FirstPerson, and Al Jazeera Your Media. In-

dymedia UK received only a single rating and so no

reliable judgements can be made about its credibil-

ity. These have all been removed from the analysis,

leaving 598 ratings in total, 26 systems rated, and an

average of 23 ratings per system (s = 8.85).

For an overview of the results, Table 1 shows the

spectrum of credibility, based on the average of all

votes received for each system. Figure 2 shows the

relationship between the average rating for each factor

and the system’s position on the openness spectrum.

As the position on the openness spectrum and the

values contributed for each factor are ordinal, we will

use Spearman’s Rank Correlation to determine rela-

tionships between the variables. The correlation be-

tween position on the spectrum and each of the fac-

tors is shown in Table 2. Each correlation is modest

though statistically significant. Table 2 also shows the

correlation when the biggest outlying systems (The

Daily Mail and The Sun, discussed below) are re-

moved.

5 DISCUSSION

Overall, we found that there is a modest correlation

between the openness of a news system and the cred-

ibility of that system. This correlation is significant

for each of the five credibility factors.

The two clear outliers in all measures are The Sun

(a populist British tabloid) and The Daily Mail (a right

wing British tabloid), which despite being very closed

systems, were rated as bottom and second bottom

overall for all credibility measures. These systems

received a number of negative comments including

“media coverage of the lowest grade”, “sensational-

ist racist tripe”, and “right wing propaganda” though

the Daily Mail did receive positive ratings from some

users, and one positive comment of “closer to the

story than some of the others”.

From the comments, the reasons for the low cred-

ibility appear to be either that these outlets are known

for overly sensational stories, or because the ideolog-

ical position of the sources significantly differ from

those of the participants. The fact that some respon-

dents did visit these websites for entertainment de-

spite finding them non-credible lends credence to the

first possibility, but the comments referring to “right

wing propaganda”, and “racist tripe” indicate that for

some it is the political position of the news source that

causes the low reputation.

Though many participants chose not to give rea-

sons for their ratings, the ones who did reveal the in-

consistencies in what people consider to be credible,

Are Open News Systems Credible? - An Investigation Into Perceptions of Participatory and Citizen News

267

Table 1: Spectrum of credibility.

Position Openness

Position

System Unbiased Fair Whole

Story

Accurate Trustworthy

1 2 BBC News 2.54 2.80 2.51 3.03 2.86

2 4 MP Expenses Investigation 2.44 2.78 2.44 2.67 2.78

3 12 Wikileaks 2.63 2.54 2.21 2.96 2.71

4 1 BBC News On Facebook 2.50 2.63 2.25 2.75 2.59

5 6 The Guardian 2.03 2.64 2.42 2.82 2.76

6 21 Wikinews 2.78 2.89 2.44 2.22 2.22

7 14 Slashdot 2.36 2.73 2.09 2.64 2.55

8 20 Flickr 2.35 2.70 2.09 2.52 2.57

9 5 Offical Google Blog 2.09 2.59 2.14 2.82 2.41

10 18 Something Awful Forum 1.27 2.41 2.18 2.45 2.55

11 19 Reddit /r/AMA 1.52 2.35 1.74 2.48 2.13

12 9 The Telegraph 1.55 2.07 2.03 2.21 2.17

13 3 Gawker 2.0 2.29 1.57 2.14 1.71

14 16 Comment Is Free (by The Guardian) 1.04 2.28 1.48 2.28 2.20

15 13 Guido Fawkes 1.25 2.00 1.88 2.13 2.00

16 10 Republic on Facebook 1.42 2.00 1.58 2.11 1.89

17 15 Huffington Post 1.54 1.96 1.68 1.86 1.89

18 11 Sky News on Twitter 1.81 1.77 1.62 1.88 1.81

19 25 Youtube 1.46 1.86 1.60 1.83 1.80

20 24 Twitter 1.47 1.72 1.38 1.72 1.66

21 17 Tumblr 1.04 1.68 1.36 1.72 1.76

22 26 Reddit /r/PoliticalDiscussion 0.88 1.44 1.25 1.88 1.50

23 22 Reddit /r/Politics 0.88 1.63 1.31 1.56 1.25

24 23 Facebook 0.86 1.40 1.09 1.09 1.09

25 7 Daily Mail 0.70 0.87 0.80 0.93 0.83

26 8 The Sun 0.50 0.63 0.46 0.71 0.50

Table 2: Correlations between openness and the five credi-

bility factors.

Factor r

s

p r

s

outliers

removed

p

Fair -.176 df = 598

p <.01

.285 df = 544

p <.01

Unbiased -.220 df = 598

p <.01

.307 df = 544

p <.01

Whole

Story

-.181 df = 598

p <.01

.272 df = 544

p <.01

Accurate -.236 df = 598

p <.01

.349 df = 544

p <.01

Trustworthy -.202 df = 598

p <.01

.315 df = 544

p <.01

and what people consider to be news.

The first thing to note from the comments is that

many participants didn’t consider some of the systems

to be news systems at all. Flickr got comments such as

“Last time I checked, Flickr was a picture upload site,

not a source of information”, “I go to Flickr for pho-

tography, not news reporting”, and “I don’t consider

Flickr a source of news”; Youtube got comments in-

cluding “This is mainly for entertainment, and is not

reliable for more serious news”, and one participant

said of Tumblr that it includes “more porn than news”.

Others felt that the broad platforms couldn’t be

judged as a whole. For example one participant said

of Slashdot “It’s information that is posted by indi-

viduals which have different levels of credibility. So

there’s no way to rate the entire platform as a whole!”,

and of Flickr “a collection of individual’s uploads,

and will reflect those people’s views. I wouldn’t ex-

pect any attempt at impartiality.”. Participants also

believed that browsing habits dictate the credibility of

the media received. For example Youtube received

comments including “It really depends on what you

watch”, and “Pretty much depends on your browsing

habits”. Twitter received the comment “Depends on

who you follow!”.

The comments did re-enforce some existing re-

search, such as the comment claiming of Youtube

that “Seeing things is better than reading about them,

doesn’t contain personal views and perspectives”

(Carter and Greenberg, 1965; Gaziano and McGrath,

1986), though others claimed that Youtube is “a soap-

box for good information and total bull at the same

time”.

When rating the more traditional systems as credi-

ble, many participants alluded to an editorial process.

For example, when rating The Guardian’s Comment

Is Free site, one participant said they “expect that The

Guardian has a system that includes quality control”

and another said that though it contains opinions, it is

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

268

“edited so probably fairer and more trusted than [Red-

dit /r/AMA]”.

The comment regarding the Guardian’s “quality

control” when referring to Comment Is Free provides

evidence that the brand name gives users confidence

in the credibility of a piece of media despite that cred-

ibility coming from a different medium. This also

came through in comments for Sky News on Twitter

(“Sky is a respectable news brand”) and BBC News

on Facebook (“generally trustworthy ... regardless of

medium”, “probably my most trusted brand”, and “of-

ficial and verified account of the BBC”).

Even in the most credible news systems there were

several comments referring to bias in the coverage.

Of the BBC, participants said “Sometimes incomplete

and a bit selective”, “sympathetic to whoever is in

power”, and “information broadcast is down to how

the organisation wants to portray a particular story”,

and The Guardian received comments such as “a pro-

nounced agenda”, “a very heavy ‘Guardian’ slant”,

and “have their own demographic to cater for, which

means that they might be selective as to the facts they

present”.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has provided an overview of credibility re-

search, and presented the results of a survey designed

to judge the credibility of 32 online websites.

We found that overall there is a modest but statis-

tically significant correlation between position on the

spectrum of openness and each of the five credibility

factors. We found that this correlation exists whether

or not we include the outliers The Daily Mail and The

Sun.

Though there were exceptions, we found that the

data gathered supports the hypothesis that more open

news systems are judged to be less credible than more

closed news systems. Judging from the comments,

the reason for The Sun and The Daily Mail not fol-

lowing this trend is due either to their reputation for

entertainment-heavy sensational stories, or due to the

difference of ideological position between the sys-

tems and the participants.

Other comments showed that there exists dis-

agreement in how the credibility of a broad platform

can be judged, and even what constitutes news. There

were some comments referring to the overall reputa-

tion of the company behind the system (such as The

BBC and The Guardian) rather than looking at the

system itself, and this was often caused by the par-

ticipant holding some trust in the editorial process as-

sociated with that company.

This provides some evidence that the ordering of

the spectrum presented by Scott et al. (2015) is a

meaningful representation of the variety of news sys-

tems, and indicates that credibility is an appropriate

but imperfect explanation of the intuitive difference

between open and closed systems.

Future work should investigate the credibility of

systems that do not fit into the openness spectrum

(such as liveblogs and microblogs), and investigate

where these systems would place on our spectrum of

credibility. Further work is also required to investi-

gate if this relationship exists in non-English language

media.

This analysis has shown that despite growing

numbers of people who share and discuss news on

open news systems, these systems lack the credibil-

ity of traditional news media. Responses indicate that

there is disagreement over whether the more open sys-

tems should be considered to be “news” at all, and in

some cases the editorial process is invoked to explain

why traditional news is the more credible option. It

may be that, to make open news systems more credi-

ble, there needs to be some form of editorial process

added.

In our own future work we will investigate spe-

cific features which affect the perceived credibility of

alternative news outlets. We hope that this work will

contribute to the design of news systems which are

both credible and open to public participation.

REFERENCES

Aalberg, T. and Curran, J. (2011). How media inform

democracy: A comparative approach, volume 1.

Routledge.

Carter, R. F. and Greenberg, B. S. (1965). Newspapers or

television: which do you believe? Journalism & Mass

Communication Quarterly, 42(1):29–34.

Chang, L. K. and Lemert, J. B. (1968). The invisible news-

man and other factors in media competition. Journal-

ism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 45(3):436–

444.

Choi, J. H., Watt, J. H., and Lynch, M. (2006). Perceptions

of news credibility about the war in iraq: Why war

opponents perceived the internet as the most credible

medium. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communi-

cation, 12(1):209–229.

Domingo, D., Quandt, T., Heinonen, A., Paulussen, S.,

Singer, J. B., and Vujnovic, M. (2008). Participatory

journalism practices in the media and beyond: An in-

ternational comparative study of initiatives in online

newspapers. Journalism practice, 2(3):326–342.

Flanagin, A. J. and Metzger, M. J. (2000). Perceptions of

internet information credibility. Journalism & Mass

Communication Quarterly, 77(3):515–540.

Are Open News Systems Credible? - An Investigation Into Perceptions of Participatory and Citizen News

269

Flanagin, A. J. and Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site

features, user attributes, and information verification

behaviors on the perceived credibility of web-based

information. New Media & Society, 9(2):319–342.

Fogg, B. J. (1999). Persuasive technologies. Communica-

tions of the ACM, 42(5):26–29.

Gaziano, C. and McGrath, K. (1986). Measuring the con-

cept of credibility. Journalism Quarterly, 63(3):451–

462.

Hellmueller, L. and Trilling, D. (2012). The credibility of

credibility measures: A meta-analysis in leading com-

munication journals, 1951 to 2011. In WAPOR 65th

Annual Conference in Hong Kong.

Johnson, T. J. and Kaye, B. K. (1998). Cruising is believ-

ing?: Comparing internet and traditional sources on

media credibility measures. Journalism & Mass Com-

munication Quarterly, 75(2):325–340.

Johnson, T. J. and Kaye, B. K. (2009). In blog we trust?

deciphering credibility of components of the internet

among politically interested internet users. Computers

in Human Behavior, 25(1):175–182.

Johnson, T. J., Kaye, B. K., Bichard, S. L., and Wong,

W. J. (2007). Every blog has its day: Politically-

interested internet users’ perceptions of blog credibil-

ity. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,

13(1):100–122.

Kim, D. and Johnson, T. J. (2009). A shift in media credi-

bility comparing internet and traditional news sources

in south korea. International Communication Gazette,

71(4):283–302.

Kiousis, S. (2001). Public trust or mistrust? perceptions of

media credibility in the information age. Mass Com-

munication & Society, 4(4):381–403.

Marchionni, D. M. (2013). Measuring conversational jour-

nalism: An experimental test of wiki, twittered and

“collaborative” news models. Studies in Media and

Communication, 1(2):119–131.

McCroskey, J. C. and Young, T. J. (1979). The use and

abuse of factor analysis in communication research.

Human Communication Research, 5(4):375–382.

Melican, D. B. and Dixon, T. L. (2008). News on the net

credibility, selective exposure, and racial prejudice.

Communication Research, 35(2):151–168.

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Eyal, K., Lemus, D. R., and

McCann, R. M. (2003). Credibility for the 21st cen-

tury: Integrating perspectives on source, message, and

media credibility in the contemporary media environ-

ment. Communication yearbook, 27:293–336.

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., and Medders, R. B. (2010).

Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evalua-

tion online. Journal of Communication, 60(3):413–

439.

Meyer, P. (1988). Defining and measuring credibility of

newspapers: Developing an index. Journalism &

Mass Communication Quarterly, 65(3):567–574.

Mitchell, A. (2014). State of the news media 2014:

Overview. Pew Research Journalism Project.

Schmierbach, M. and Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2012). A little

bird told me, so i didn’t believe it: Twitter, credibil-

ity, and issue perceptions. Communication Quarterly,

60(3):317–337.

Schweiger, W. (2000). Media credibility—experience or

image? a survey on the credibility of the world wide

web in germany in comparison to other media. Euro-

pean Journal of Communication, 15(1):37–59.

Scott, J., Millard, D., and Leonard, P. (2015). Citizen par-

ticipation in news. Digital Journalism, 3(5):737–758.

Sundar, S. S., Knobloch-Westerwick, S., and Hastall, M. R.

(2007). News cues: Information scent and cognitive

heuristics. Journal of the American Society for Infor-

mation Science and Technology, 58(3):366–378.

Sundar, S. S. and Nass, C. (2001). Conceptualizing sources

in online news. Journal of Communication, 51(1):52–

72.

Thorson, E. and Duffy, M. (2006). A needs-based theory of

the revolution in news use and its implications for the

newspaper business. Technical report, Reynolds Jour-

nalism Institute at the Missouri School of Journalism,

Columbia, MO.

Thorson, K., Vraga, E., and Ekdale, B. (2010). Credibil-

ity in context: How uncivil online commentary affects

news credibility. Mass Communication and Society,

13(3):289–313.

Tseng, S. and Fogg, B. (1999). Credibility and computing

technology. Communications of the ACM, 42(5):39–

44.

Wathen, C. N. and Burkell, J. (2002). Believe it or not:

Factors influencing credibility on the web. Journal

of the American society for information science and

technology, 53(2):134–144.

West, M. D. (1994). Validating a scale for the measure-

ment of credibility: A covariance structure modeling

approach. Journalism Quarterly, 71(1):159–68.

Wilson, C. E. and Howard, D. M. (1978). Public perception

of media accuracy. Journalism Quarterly.

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

270