Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges

Improved EA Adoption Method

Nestori Syynimaa

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

School of Information Sciences, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

CSC - IT Center for Science, Espoo, Finland

Keywords: Enterprise Architecture, Adoption Method, Design Science, Delphi.

Abstract: During the last decades the interest towards Enterprise Architecture (EA) has increased among both

practitioners and scholars. One of the reason behind this interest is the anticipated benefits resulting from its

adoption. EA has been argued to reduce costs, standardise technology, improve processes, and provide

strategic differentiation. Despite these benefits the EA adoption rate and maturity are low and, consequently,

the benefits are not realised. The support of top-management has been found to be a critical success factor for

EA adoption. However, EA is often not properly understood by top-management. This is problematic as the

value of EA depends on how it is understood. This paper aims for minimising the effect of this deficiency by

proposing Enterprise Architecture Adoption Method (EAAM). EAAM improves the traditional EA adoption

method by introducing processes helping to secure the support of top-management and to increase EA

understanding. EAAM is built using Design Science approach and evaluated using Delphi.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprise Architecture (EA) has received a lot of

attention during the last decades. For instance, the

ICEIS conference have had a dedicated EA track for

some years now. One of the reasons for the increased

interest is the anticipated benefits resulting from its

adoption. EA has been argued to provide cost

reduction, technology standardisation, process

improvement, and strategic differentiation

(Schulman, 2003). Using a set of case-studies, Ross

et al. (2006) demonstrated how these benefits could

create value to organisations. Despite these benefits

to be gained, EA is not widely adopted in

organisations (Schekkerman, 2005; Computer

Economics, 2014). Top-management support has

been found to be a key success factor for adopting EA

(Kaisler et al., 2005). However, EA is not often

understood correctly (Hjort-Madsen, 2006;

Sembiring et al., 2011; Lemmetti and Pekkola, 2012;

Hiekkanen et al., 2013). Business managers regards

EA as an IT issue and IT managers as too big effort

(Bernard, 2012).This equation is problematic as the

value of EA to organisation depends on how it is

understood by top-management (Nassiff, 2012).

In this paper, we propose an improved EA

adoption method to address the aforementioned

issues. The proposed method helps organisations to

adopt EA and, concequently, realise the EA benefits.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First we

introduce the key concepts of EA, the traditional EA

adoption process, and some adoption challenges. This

is followed by the introduction of the research

methodology of the paper. Next the proposal for

improved Enterprise Architecture Adoption Method

(EAAM) is introduced. Finally, discussion and

directions for future research are provided.

1.1 Enterprise Architecture

Enterprise Architecture has many definitions in the

current literature. Vague definitions are confusing for

both practitioners and scholars (Hjort-Madsen, 2006;

Sembiring et al., 2011; Valtonen et al., 2011;

Lemmetti and Pekkola, 2012; Pehkonen, 2013). EA

can be seen as a verb, something we do, and as a noun,

something we produce (Fehskens, 2015). From the

various definitions in the literature (i.e., Zachman,

1997; CIO Council, 2001; TOGAF, 2009;

ISO/IEC/IEEE, 2011; Gartner, 2013; Dietz et al.,

2013) we adopt the synthesis by Syynimaa (2013):

“Enterprise Architecture can be defined as; (i) a

formal description of the current and future state(s) of

an organisation, and (ii) a managed change between

506

Syynimaa, N.

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method.

In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016) - Volume 2, pages 506-517

ISBN: 978-989-758-187-8

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

these states to meet organisation’s stakeholders’ goals

and to create value to the organisation”. As such, we

accept the dual meaning of EA as a noun and verb.

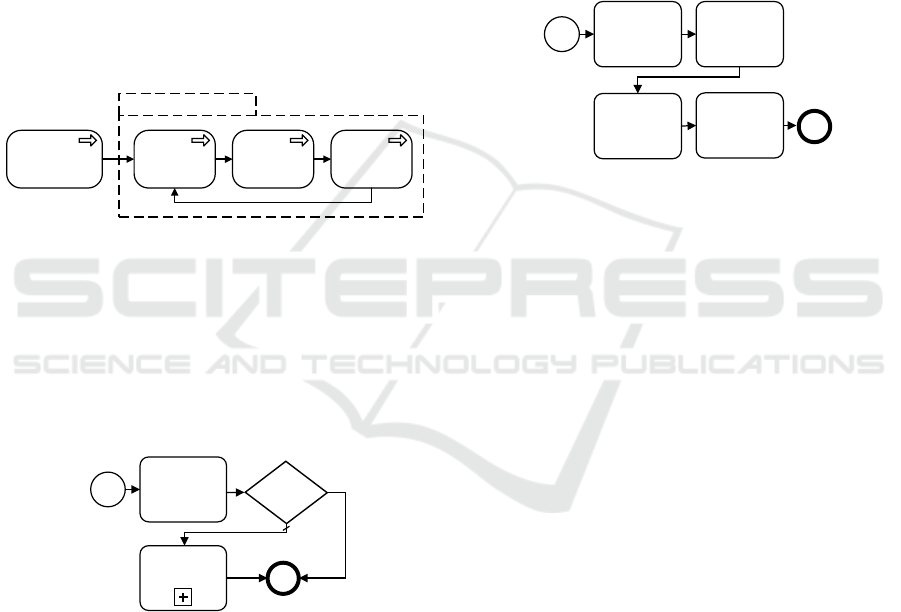

With this definition in mind we can identify three

processes related to EA development cycle. These are

illustrated in Figure 1 using ArchiMate notation. The

first process (P1) is describing the current state of the

organisation and the second process (P2) the future

state of the organisation. Difference between these two

is that P1 is merely a description of the current state of

the organisation, whereas P2 includes also elements of

planning. The third process (P3) is the managed change

where the (planned) future state of the organisation is

implemented. There is also a fourth process related to

EA, the adoption (P0), which precedes the other three

processes. During the adoption, the state of the

organisation is changes from the state where EA is not

adopted to the state where it is adopted.

Figure 1: Enterprise Architecture Processes.

1.2 Enterprise Architecture Adoption

Enterprise Architecture adoption is a process where

an organisation starts using EA methods and tools for

the very first time. It is an instance of teleological

organisational change (see van de Ven and Poole,

1995) aiming for the realisation of EA benefits.

Figure 2: Traditional EA Adoption Process (P0).

The traditional EA adoption process is illustrated

in Figure 2 using BPMN 2.0 notation. It is a high level

process consisting of two activities. The mandate for

the EA adoption is seen crucial by both scholars and

practitioners (North et al., 2004; Kaisler et al., 2005;

Shupe and Behling, 2006; Gregor et al., 2007; Iyamu,

2009; 2011; Liu and Li, 2009; Carrillo et al., 2010;

Mezzanotte et al., 2010; Vasilescu, 2012; Struijs et

al., 2013). Therefore the first activity is to acquire a

mandate for EA adoption. If the mandate is not given

the adoption process terminates. If the mandate is

given the process continues to the next activity called

Conduct EA adoption. This collapsed sub-process is

expanded in Figure 3. The first task in the Conduct

EA Adoption process is to select EA framework. EA

frameworks, such as TOGAF, usually consists of a

development method and a governance model which

are distinctive to the framework. Therefore the

remaining tasks of the process depends on the

selected framework. As it can be noted, the remaining

tasks are same than the processes P2, P3, and P4. This

is because during the adoption these steps are

executed once before entering the normal EA

development cycle.

Figure 3: Conduct EA Adoption Process (P0.2).

1.3 EA Adoption Challenges

As stated, EA adoption is an organisational change

aiming for the realisation of EA benefits. According

to several studies, about 70 per cent of organisational

change initiatives fail (Hammer and Champy, 1993;

Beer and Nohria, 2000; Kotter, 2008). This is also the

case with EA adoption. Consequently, the anticipated

benefits of adopting EA are not realised.

For instance in Finland, EA is made mandatory in

public sector by legistlation (Finnish Ministry of

Finance, 2011). The Act of Information Management

Governance in Public Administration requires public

sector organisations to adopt EA by 2014. In 2014 the

EA maturity in the state administration was 2.6 or

below in the 5 level TOGAF maturity-model (Finnish

Ministry of Finance, 2015). Several studies has found

that EA is not well understood in Finnish public

sector (Hiekkanen et al., 2013; Lemmetti and

Pekkola, 2012; Seppänen, 2014; Syynimaa, 2015).

According to Seppänen (2014) and Syynimaa (2015),

the lack of EA knowledge is one of the main reasons

hindering EA adoption

2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

In this paper we have adopted Design Science (DS)

approach (see Hevner et al., 2004) to improve the

P1:

Describe the

current state

P2:

Describe the

future state

P3:

Managed

Change

P0:

Adopt Enterprise

Architecture

EA Development Cycle

Yes

Got

mandate?

Acquire

Mandate

Conduct EA

Adoption

No

Start

End

Select EA

Framework

Describe the

current

state

Describe the

future state

Managed

Change

Start

End

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

507

traditional EA adoption method. DS is a research

approach aiming to create scientific knowledge by

designing and building artefacts (van Aken, 2004). As

such, DS is concerned about the utility value of the

resulting artefacts (Vaishnavi and Kuechler, 2013).

There are three types of artefacts to research: (i) a

technology artefact, (ii) an information artefact, and

(iii) social artefact (Lee et al., 2015). In this paper we

are building a method, which according to Lee et al.

(ibid.) is a technology artefact.

This paper follows the Design Science Research

Model (DSRM) by Peffers et al. (2007). DSRM

process consists of six phases: (i) problem

identification and motivation, (ii) defining objectives

for a solution, (iii) designing and developing an

artefact, (iv) demonstration of the usage of the

artefact, (v) evaluation of artefact’s utility, and (vi)

communication.

Typical outcome of DS is a tested and grounded

Technological Rule (TR), which can be defined as “a

chunk of general knowledge, linking an intervention

or artefact with a desired outcome or performance in

a certain field of application" (van Aken, 2004, p.

228). The form of a TR is "if you want to achieve Y

in situation Z, then perform action X" (ibid., p. 227).

Tested TR means a rule which has been tested in the

context it is intented to be used (Houkes, 2013).

Grounded TR (GTR) is a rule which reasons for its

effectivness are known (Bunge, 1966; Houkes, 2013).

In this paper, we will seek for GTRs which would

improve the traditional EA adoption method to

address the adoption issues related to the lack of EA

knowledge.

EA adoption is a process where the current state

of the organisation is changed. This is comparable to

the DS problem-solving situation illustrated in Figure

4. The desired state of EA adoption is the organisation

where EA is adopted and embedded to organisation’s

processes. However, it is possible to end up with a

final state where the desired state is not achieved or it

is achieved only partially. In order to evaluate

whether the improved EA adoption method works as

intented, we should perform the adoption using the

method in a real-life setting. Given the time and

resources required by EA adoption, real-life

evaluation is practically not possible. Therefore, we

will adopt a Delphi method to evaluate the utility of

the method.

Delphi method is a research process where

experts’ judgements about the subject are iteratively

and anomynously collected and refined by feedback

(Skulmoski et al., 2007). It is typically used in

forecasting but can be used also when developing

methods (Päivärinta et al., 2011).

Figure 4: DS problem-solving situation (Järvinen, 2015).

As stated earlier, various studies have noticed the

lack of EA knowledge in organisations. For instance

Lemmetti and Pekkola (2012) argues that current

definitions of EA are inconsistent and thus confusing

both practitioners and scholars. Indeed, EA is

underutilised due to lack of understanding it properly

(Hiekkanen et al., 2013). Therefore, our problem

definition for EAAM is as follows: How to minimise

the effects of the lack of understanding EA concepts

to EA adoption process? This leads to the objective

of EAAM, which is to improve the traditional EA

adoption method to minimise the effect of lack of

understanding of EA concepts.

3 ENTERPRISE ARCHITECTURE

ADOPTION METHOD

In this section we will introduce the Enterprise

Architecture Adoption Method (EAAM) and describe

its building and evaluation. First we introduce and

discuss on various organisational learning and change

theories affecting EA adoption. Based on these, we

will introduce GTRs to form a descriptive model.

This is followed by the introduction of our emerging

prescriptive method, EAAM. EAAM consists of the

traditional EA adoption method with additional

processes implementing the GTRs. Finally, the

evaluation of EAAM is described.

3.1 Readiness for Change

Besides organisation culture (Burnes and James,

1995), the readiness for change has an impact on

successful change (Jones et al., 2005). According to

Holt et al. (2007) the most influential factors of

change readiness are (i) discrepancy (the belief that a

change was necessary), (ii) efficacy (the belief that the

change could be implemented), (iii) organisational

valence (the belief that the change would be

organizationally beneficial), (iv) management

support (the belief that the organisational leaders

were committed to the change), and (v) personal

valence (the belief that the change would be

personally beneficial). (Holt et al., 2007). This

implies that the content, context, and process of EA

An initial state A building process A desired state

A final state

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

508

adoption together with individual attributes affects

the readiness for EA adoption. More specifically,

individuals should believe that EA adoption is

necessary, possible, beneficial to organisation, and

supported by top-management. They should also feel

that EA adoption would be beneficial to themselves.

Similarly, managers who understand the change

efforts are less resistant to change (Washington and

Hacker, 2005).

Communication has an important role in

organisational change. Communication has a positive

effect to the readiness for change (Elving, 2005). On

the other hand, uncertainty has a negative effect to

readiness for change. This can also be influenced by

communication. This implies that the readiness for

EA adoption can be increased by communication,

either directly or by decreasing uncertainty.

General technology acceptance models (see for

example Venkatesh et al., 2003) suggests that

individual acceptance of information technology (IT)

is influenced by beliefs and attitudes, which in turn is

influenced by Managerial interventions and

Individual differences. Individual acceptance is

conceptually similar to the readiness for change. Both

are influenced by beliefs and attitudes. These beliefs

can be influenced by managerial intervention, e.g.,

communication. Therefore, in order to increase the

likelihood of EA adoption success, the readiness for

change needs to be increased by a proper

communication by managers.

3.2 Individual and Organisational

Learning

Learning can be defined as a transformation where

“the initial state in the learner’s mind is transformed

to the new state which is different from the initial state

if learning has occurred.” (Koponen, 2009, p. 14,

italics removed). State of mind consists of following

cognitive beliefs; beliefs (knowledge), values, and

know-how (including skills). If learning occurs, the

state of mind is transferred to a new state of mind with

different cognitive beliefs. Learning can occur

through acts in reality or by learner’s own thinking.

The former learning mode means learning by

perceptions, by having new experiences, or by

acquiring information. (Koponen, 2009).

The current position of IS research is rooted in

methodological individualism, which sees

organisations as collection of individuals (Lee, 2010).

This theoretical point of view is problematic, as it

suggests that if the new people are coming in to the

organisation, a new organisation would emerge (Lee,

2004). Therefore, according to Lee (2004), the better

conceptualisation would be that the organisation stays

(somewhat) the same, and the people moving in

would change towards the organisation’s culture.

Organisational learning can be explained using 4I

framework, where learning occurs on individual,

group, and organisational levels. These levels are

linked by four processes; intuiting, interpreting,

integrating, and institutionalising. “Intuiting is a

subconscious process that occurs at the level of the

individual. It is the start of learning and must happen

in a single mind. Interpreting then picks up on the

conscious elements of this individual learning and

shares it at the group level. Integrating follows to

change collective understanding at the group level

and bridges to the level of the whole organization.

Finally, institutionalising incorporates that learning

across the organization by imbedding it in its systems,

structures, routines, and practices" (Mintzberg et al.,

1998, p. 212).

Individual learning is in a crucial part on the

organisational learning, as organisations are “after all,

a collection of people and what the organisation does

is done by people" (March and Simon, 1958). Also,

“change is not just about how people act, but it is also

about how they think as well." (Kitchen and Daly,

2002, p. 49). It can said that organisational learning

has occurred, when EA concepts are understood on

individual level, and processes and methods adopted

and embedded to organisation’s routines.

Individual and organisational learning has direct

implications to EA adoption. Organisational level

learning occurs only through individuals. Similarly,

individuals learn from the organisation. However,

organisation is not the only source of learning for

individuals. Learning may occur whenever the

individual is interacting with reality (i.e.,

communicating, perceiving, observing) but also by

barely thinking (Koponen, 2009). In order to adopt

EA in an organisation, individuals needs to learn EA.

3.3 Effects of EA Training and

Understanding EA Benefits

Hazen et al. (2014) studied why EA is not used to a

degree which realises its benefits. The study is based

on the UTAUT by Venkatesh et al. (2003). The study

is especially interested in which performance

expectancy drives organisational acceptance of EA.

Performance expectancy is defined as “the degree to

which an individual believes that using the system

will help him or her to attain gains in job

performance” (ibid., 2003, p. 447). According to

findings, partial mediation model explains the EA

use significantly more than full or no mediation

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

509

models. The partial mediation model implies that in

order to increase EA knowledge, individuals’

performance expectancy of EA needs to be increased

along with proper EA training.

Nassiff (2012) studied why EA is not more widely

adopted by analysing how organisation’s executives

value EA. According to findings, EA has four

meanings among executives; Business and IT

alignment, a holistic representation of the enterprise,

a planned vision of the enterprise, and a process,

methodology, or framework enhancing enterprise

decision making. Also 16 unique benefits of EA were

identified. Value of EA is directly influenced by how

the EA is understood in the organisation. Regardless

of the meaning of EA, three common benefits were

expected; alignment between business and IT, better

decisions making, and the simplification of system or

architecture management. Findings implies that in

order to increase the individual’s performance

expectancy of EA adoption, EA benefits needs to be

communicated according to what EA means to the

individual. This implication actually means also

adopting andragogy instead of pedagogy as an

assumption of learning; individual learning is

depending on and occurring on top of the past

experiences of the individual (Knowles, 1970). These

past experiences and existing “knowledge” can have

a negative effect to learning EA adoption, as

individuals “have a strong tendency to reject ideas

that fail to fit our preconceptions” (Mezirow, 1997, p.

5).

3.4 Role of Managerial Intervention

and Leadership Style

Makiya (2012) has studied factors influencing EA

assimilation within the U.S. federal government. EA

was adopted gradually, starting from adoption (as

defined in this paper) ending to assimilating EA as an

integral part of organisation. The research was

divided in to three three-year phases. During the first

phase (e.g., adoption) factors like parochialisms and

cultural resistance, organisation complexity, and

organisation scope had a significant influence.

According to the findings, parochialisms and cultural

resistance did not exist in phase two, likely due to

coercive pressure by organisation. This can be

interpreted so that by using a force mandated by

organisational position, one can greatly influence EA

adoption. This is conceptually similar to managerial

intervention, but also to situational and social

influence. It should be noted that this approach had no

effect in the phase three, so it should be utilised only

during the adoption phase. According to study,

labelling EA as an administrative innovation instead

of a strategic tool could help in value perception and

adoption of EA.

Vera and Crossan (2004) has expanded the model

of organisational learning by Crossan et al. (1999).

They added the concept of learning stocks. Learning

stocks exists in each level of organisational learning,

namely individual, group, and organisation levels.

These learning stocks contains the inputs and outputs

of learning processes, taking place between layers.

They argue that different leadership styles

(transactional or transformational) needs to be used

based on which type of organisational learning (feed-

forward of feedback) needs to be promoted.

There are some behavioural differences between

transactional and transformational leadership styles.

These styles are not exclusive but should be used

accordingly based on the situation (Vera and Crossan,

2004). Transactional leadership is based on

“transactions” between the manager and employees

(Bass, 1990). They are performing their managerial

tasks by rewards and by either actively or passively

handling any exceptions to agreed employee actions.

Transformational leadership style aims to elevating

the interests of employees by generating awareness

and acceptance of the purpose of the group or

initiative (Bass, 1990). This is achieved by utilising

charisma, through inspiring, intellectual stimulation,

and by giving personal attention to employees. Thus

it can be argued that transactional leadership style

suits better in a situation where status quo should be

maintained. Similarly, transformational leadership

style works better in a situation where organisation

faces changes.

The feed-forward learning allows organisation to

innovate and renew, whereas the feedback process

reinforces what has already learned. There can be two

types learning; learning that reinforces

institutionalised learning and learning that challenges

institutionalised learning. Transformational

leadership have a positive impact to learning when

current institutionalised learning is challenged, and

when organisation is in a turbulent situation. In turn,

transactional leadership have positive impact to

learning when the institutionalised learning is

reinforced, and when organisation is in a steady

phase. (Vera and Crossan, 2004).

The role of managerial or leadership style to

organisational and individual learning is significant.

The key is the current organisational learning stock or

institutionalised learning regarding to EA adoption. If

EA adoption conflicts with the current

institutionalised learning, the transformational

leadership should be used in order increase the feed-

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

510

forward learning. Vice versa, if EA adoption does not

conflict with the current institutionalised learning, the

transactional leadership should be used to increase

feedback learning.

Espinosa et al. (2011) have studied the

coordination of EA, focusing on increasing

understanding how coordination and best practices

lead to EA success. According to study, cognitive

coordination plays a critical role in effectiveness of

architecting. Their model consists of two models,

static and dynamic models. Whereas the static model

affects the effectiveness on “daily basis”, a dynamic

model strengthens group cognition over the time.

There are three coordination processes in the model:

organic, mechanistic, and cognitive. Mechanistic

coordination refers to coordination of the routine

aspects with minimal communication by using

processes, routines, specification, etc. Organic

coordination refers to communication processes used

in more uncertain and less routine tasks. Cognitive

coordination is achieved implicitly when each

collaborator have knowledge about each other’s

tasks, helping them to anticipate and thus coordinate

with a reduced but more effective communication. As

it can be noted, the term “cognitive” is not referring

to term cognition, which is usually defined as a

“mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and

understanding through thought, experience, and the

senses” (Oxford Dictionaries, 2010). Instead, they are

referring to the shared cognition of a high

performance group of individuals having similar or

compatible knowledge, which can coordinate its

actions without the need for communication

(Cannon-Bowers and Salas, 2001).

According to the findings by Espinosa et al.

(2011), cognitive coordination plays a central role in

strengthening the other two coordination

mechanisms. Therefore, in order increase the

effectiveness of EA adoption, the shared cognition of

individuals within the organisation needs to be

strengthened. This can be achieved by providing

similar level of EA knowledge to all individuals

3.5 Emerging EA Adoption Method

In this sub-section, we first sum up the concepts

presented in previous sub-sections and form a list of

propositions based on these concepts and their

interrelations (Table 1). Based on these proposition,

six Ground Technological Rules (GTRs) are

presented, and finally EAAM process descriptions are

introduced.

Table 1: Propositions of EA Adoption Method.

ID Explanation Source

P1 Understanding EA

Benefits influences

Performance Expectancy

Nassiff (2012)

P2 Executive’s

understanding of EA

meaning influences

benefits

Nassiff (2012)

P3 Performance Expectancy

influences EA training

Hazen et al. (2014)

P4 Individual’s and

organisation’s learning

stocks influences each

other

Crossan et al. (1999)

P5 Performance Expectancy

influences EA adoption

Hazen et al. (2014)

P6 Managerial Intervention

influences feed-forward

and feedback learning

Crossan et al. (1999)

P7 Individual’s learning

stock influences EA

Adoption

Agarwal (2000)

Elving (2005)

Espinosa et al. (2011)

Hazen et al. (2014)

Holt et al. (2007)

P8 Executives Individual

Attributes influences

leadership style

Bass (1990)

Crossan et al. (1999)

P9 Managerial Invention

influences EA Adoption

Agarwal (2000)

Makiya (2012)

By EA Benefits we refer to all those benefits that

may result by adopting Enterprise Architecture.

These benefits influences Performance Expectancy

(PE), which refers to individual’s expectations

towards EA adoption (P1). Individual’s Learning

Stock refers to all individual’s current knowledge,

know-how, values, and processes related on changing

these (i.e. learning). Performance Expectancy

influences Individual’s Learning Stock (P3) by giving

some meaning to EA’s performance properties.

Performance Expectancy also has a direct influence

to EA Adoption (P5). Individual’s Learning Stock

influences EA Adoption (P7), as it contains all

individual’s knowledge, know-how, and values

related to Enterprise Architecture. Managers’ and

executives’ Individual Learning Stock influences EA

Benefits (P2) in terms of his or hers capability to

comprehend possible benefits related to EA adoption.

Similarly, managers’ and executives’ Individual

Learning Stock influences how they are capable in

using Managerial Intervention to increase EA

adoption success (P8). Organisation’s Learning

Stock refers to the current organisation’s

institutionalised knowledge (i.e., patents), know-how

(i.e., processes, instructions, rules), and values (i.e.,

culture). Feed-forward and feedback learning occurs

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

511

between Organisation’s Learning Stock and

Individual’s Learning Stock (P4). As organisations

are composed of its members, changes in

Organisation’s Learning Stock (i.e., organisational

learning) may only occur through Individual’s

Learning Stock. Organisation’s Learning Stock

however is only one of many sources that influences

Individual’s Learning Stock. Managerial

Intervention refers to those actions which

organisation’s managers and executives may use to

increase the success of EA adoption. Managerial

Intervention has a direct influence on EA Adoption

(P9), as managers and executives may provide

coercive pressure to “force” EA adoption.

Managerial Intervention influences also

organisational learning (P6) taking place between

Individual’s and Organisation’s Learning Stocks

where managers and executives may promote

learning by choosing their leadership style

accordingly.

Based on the propositions six GTRs are provided

in Table 2. As suggested by propositions P1, P2, P3,

P4, P5, and P7, understanding EA benefits influences

the EA adoption indirectly through performance

expectancy and individual’s learning stock. In order

to acquire the mandate for EA adoption from the top-

management, GTRs R1 to R4 are provided. As

suggested by propositions P6 and P9, managerial

intervention influences EA adoption both directly and

indirectly by influencing organisational learning. To

influence this learning, GTRs R5 and R6 are

provided.

Based on the propositions and the GTRs provided

above, three process descriptions are formed using

BPMN 2.0 notation. First description, EA adoption

process, can be seen in Figure 5. The process consists

of four tasks; Explain EA benefits, Acquire Mandate,

Organise EA learning, and Conduct EA adoption.

When compared to the traditional EA adoption

process seen in Figure 2 two tasks are added

(illustrated in grey in Figure 5). The first new task, a

collapsed sub-process of Explaing EA Benefits is

expanded in Figure 6. The second new task, a

collapset sub-process of Organising EA Training is

explanded in Figure 7. The logic of the process is as

follows. A mandate from top management of the

organisation is a requirement for EA adoption. In

order to increase the likelihood of getting the

mandate, one needs to explain the benefits of EA to

management. If mandate is given, the next task is to

organise EA training to increase the understanding of

EA concepts. After these tasks are completed, the

actual EA adoption can be started.

Table 2: Grounded Technological Rules.

ID Explanation

R1 If you want to acquire a mandate for Enterprise

Architecture adoption from top-management,

explain Common EA Benefits.

R2 If you want to acquire a mandate for Enterprise

Architecture adoption from top-management in a

situation where manager’s

• view to EA is more business oriented,

• rating of the organisation’s EA maturity is

low, or EA experience is low, explain

Alignment Specific Benefits.

R3 If you want to acquire a mandate for Enterprise

Architecture adoption from top-management in a

situation where manager’s

• EA experience is high,

• perception of EA complexity is low, or

current EA authority is low, explain Planned

Vision Specific Benefits.

R4 If you want to acquire a mandate for Enterprise

Architecture adoption from top-management in a

situation where manager’s

• current EA authority is high, explain Decision

Making Specific Benefits.

R5 If you want to improve organisational learning

during EA adoption in a situation where

• EA challenges the current organisational

learning, use Transformational Leadership

Style. Otherwise use Transactional

Leadership Style.

R6 If you want to improve EA adoption, use Coercive

Organisational Pressure.

Figure 5: Improved EA Adoption Process.

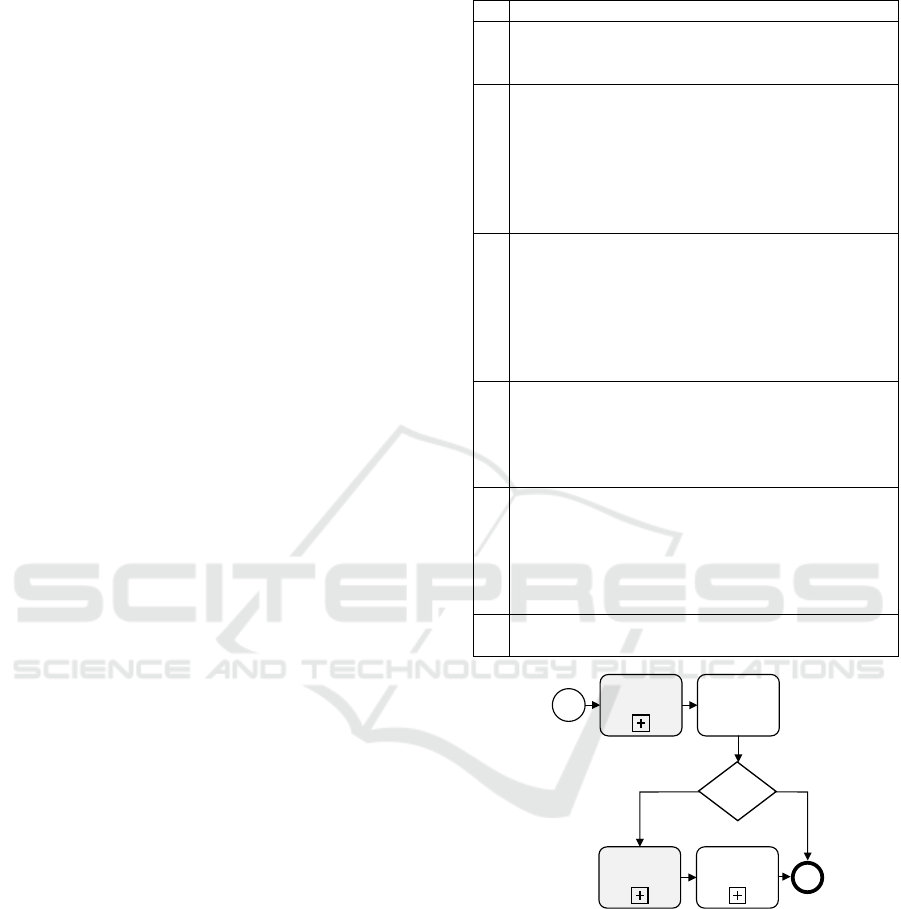

The process of explaining EA benefits can be seen

in Figure 6. This process has two actors, the EA

responsible and Manager. The manager refers to the

manager or executive whose support to EA adoption

is seen as important.

The first task of the process is to explain common

EA benefits, such as alignment of business and IT.

Next task is to assess manager’s views to EA in terms

of EA business orientation, organisation’s EA

maturity, EA experience, perception of EA’s

complexity, and current EA authority. Based on the

Acquire

Mandate

Start

End

Got

mandate?

Organise EA

training

Conduct EA

Adoption

Yes No

Explain EA

Benefits

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

512

assessments, one should explain the more specific EA

benefits accordingly. For example if the manager’s

EA experience is low, one should explain the benefits

specific to alignment, such as increased operational

effectiveness and process improvements.

The process of providing EA training can be seen

Figure 7. This process has also two actors, EA

responsible and Employees, which represents

organisation’s personnel. First task is to assess

organisation’s current learning stock, i.e. what is

organisation’s current knowledge, know-how, and

values related to Enterprise Architecture. As we are in

the adoption phase, the level of EA specific knowledge

is ought to be low, but one should assess capabilities and

practices such as project management, change

management, and internal communication. Second task

is to assess employee’s learning stock. Based on these

two learning stock assessments, one should choose a

proper leadership style. If EA adoption challenges

institutionalised learning, i.e. it is different than status

quo, one should choose to use transformational

leadership style. If the learning does not challenge

institutionalised learning, one should choose to use

transactional leadership style. By using the chosen

leadership style, next task is to promote learning

accordingly. Next task is to provide EA learning based

on assessments of current learning stocks. The last task

is to use coercive organisational pressure.

3.6 Evaluation

Purpose of the evaluation of our Enterprise

Architecture Adoption Method (EAAM) is to assess

whether it has the intended affect. The evaluation

design follows the guidelines by Venable et al.

(2012). Target of the evaluation is the product,

EAAM, and evaluation takes place ex-post. The

audience of EAAM is mainly EA responsible, i.e., EA

champions, project managers, EA architects, etc.

Delphi method was selected as an evaluation

method. For the evalution, a panel of top Finnish EA

experts was carefully selected from both industry and

academia. Panel consisted of 11 members of different

roles; professors (2), CIOs (3), consultants (2), EA

architects (2), and development managers/directors

(2). Evaluation consists of three rounds.

For the first round, using open-ended questions,

experts were asked to read the EAAM method

description and compare it to the traditional adoption

method. For the second round, first round answers

(n=31) were transformed to claims and sent back to

experts for rating (disagree-neutral-agree). The scale

(-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3) was formed so that it could be

treated as an interval scale as defined by Stevens

(1946) which allowed us to calculate mean and

standard deviations. For the third round, claims were

sent to experts for rating including the average

opinion of the panel. This allowed experts to re-assess

their opinions to each claim.

The purpose of the evaluation is to have an

unanimous opinion of the experts about EAAM. Thus

the interest lies in the claims having a high mean and

low standard deviation. Claims were ordered by their

z-scores calculated with the formula z=(x-µ)/σ

Figure 6: Explain EA Benefits Process.

Figure 7: Organise EA Training Process.

Explain

Common EA

Benefits

Start

End

Yes

EA Responsible

Assess

Managers’

Views to EA

EA

business

oriented?

Explain alignment benefits

Low EA

maturity?

Low EA

experience?

Yes Yes

Manager

Yes

High EA

experience?

Explain planned vision benefits

Low EA

complexity?

Yes

Low EA

authority?

Yes

High EA

authority?

Yes

Explain decision

making benefits

Assess

organisation’s

learning stock

Start

EA Responsible

EA challenges

institutionalised

knowledge?

Yes

Employee

Assess

employee’s

learning stock

Use

transformational

leadership style

Use transactional

leadership style

No

End

Promote

training

Provide EA

training

Use coersive

organisational

pressure

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

513

where x is the mean value of the particular claim, µ is

0 (the centre of the scale), and σ is the standard

deviation of the particular claim. The higher the z-

score is, the more unanimous are the experts. To

include only the most unanimous claims, a critical z-

value for 0.95 significance was used as a threshold.

The critical value for 0.95 is 1.65 as calculated by

Excel 2007 NORMSINV function. Claims with the z-

score less than 1.65 are thus rejected, which leaves us

16 statements of EAAM seen in Table 3.

Table 3: Evaluation Statements.

z Statement

5.33 Considered and appropriate leadership style

helps in adoption because it is all about changing

the way to perform development.

4.64 Benefits of the adoption and the temporal

nature of the resulting extra work is understood

b

etter, because the benefits are communicated using

the target group’s comprehension and point of view.

3.77 The meaning of the top-management’s own

example for the organisation is becoming more

aware, because by the commitment of the top-

management also the rest of the organisation is

obligated to the EA adoption.

3.33 IM department's estimates of change targets are

improved, because the anticipation of changes are

improved and visualised.

2.83 The average of organisation's individuals'

willingness to change will change to more positive,

because the communication of benefits increases

the formation of positive image and the

acquirement the mandate from top-management.

2.67 The reasons for actions will be communicated.

2.67 Top-managements support to EA as a

continuous part of organisation’s normal

management and operational development

increases, because the recognition of the purpose

and justification of EA-work, and communication

of benefits, builds the foundation to acquire the

mandate of top-management.

2.36 The total development of organisational

knowledge would be improved in general, because

also other actors beside the top-management are

taken into account.

2.36 The leadership point of view is correct because

the communication of EA is shaped according to

the target group.

2.13 Setting the target and objectives of the adoption

can be performed faster and in managed manner

because the participants has a common picture of

concepts, objectives, and methods before the actual

execution phase.

2.04 The commitment and motivation to the

adoption increases, because the understanding of

reasons and objectives of EA increases.

z Statement

1.85 Effects to the quality of results and to

communicating them are positive, because the

meaning of broad-enough knowledge is

emphasised.

1.76 Documentation of QA system is improved,

because method has a positive effect in the creation

of basic documentation

1.76 Improves commitments and possibilities to

acquire the mandate, because the person responsible

for adoption is helped to improve targeting and

content of the communication, and to considering

the appropriate influencing methods and

approaches.

1.76 Definitions of the roles and tasks are naturally

forming according to the target, because the

communication using the language of the target

group affects the understanding of the benefits of

each group.

1.67

Securing of top-management’s commitment to

adoption of EA and similar concepts increases,

because the adoption is strongly based on top-

management’s commitment and communication of

the adoption.

4 DISCUSSION

As stated in the problem definition, the purpose of the

EAAM is to improve the traditional EA adoption

process to minimise the effects of lack of

understanding EA concepts. For this purpose, EAAM

introduced two sub-processes: Explain EA benefits

and Organise EA learning.

Goal of the Explain EA benefits process is to

increase the likelihood of getting a mandate from top-

management for EA adoption. This is achieved by

explaining EA benefits based on each manager’s

characteristics. Experts’ statements supports

achievement of this goal strongly, as most of the

statements are related to this process. This also

indicates the importance of securing top-management

mandate.

Goal of the Organise EA learning process is to

increase the understanding of EA concepts. This is

achieved by assessing the current learning stock and

by providing appropriate training with a help of

appropriate leadership style. Experts’ statements

supports also achievement of this goal.

According to March and Smith (1995, p. 261)

“Evaluation of methods considers operationality (the

ability to perform the intended task or the ability of

humans to effectively use the method if it is not

algorithmic), efficiency, generality, and ease of use”.

The first two criteria, operationality and efficiency is

evaluated above; EAAM can be used to perform

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

514

intended task (e.g., adopt EA in an organisation) and

it is efficient. The last two criteria, generality and ease

of use, can be evaluated only by applying EAAM in

other settings.

We cannot be argued that EAAM would be the

best alternative solution to the traditional EA

adoption method. However, as demonstrated in

previous section, it can be argued that EAAM is better

than the traditional EA adoption method.

4.1 Limitations and Future Work

As with all research this research is not without

limitations. EAAM was evaluated with a panel of EA

experts utilising the Delphi method. Therefore the

first direction for future work is to evaluate it in a real-

life setting by instantiation. The Canonical Action

Research (CAR) by Davison et al. (2004) can be

utilised as a research method during the instantiation.

As suggested by Venkatesh et al. (2003), ease-of-use

is important. In this paper, the ease-of-use of EAAM

was not assessed. Therefore, the second direction for

future research is to assess EAAM’s ease-of-use in a

real-life setting.

4.2 Conclusions

The EAAM method emphasises the importance of

acquiring the mandate for EA adoption from the top-

management and the importance of a proper EA

training. EAAM helps in acquiring the mandate by

formulating the argumentation of EA benefits

according to the individual’s interests. Moreover,

EAAM helps in EA training by providing directions

in choosing a proper leadership style to promote EA

training. Thus by following EAAM, organisations

can minimise the effects of the lack of EA knowledge.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R. (2000). Individual acceptance of information

technologies. In: Zmud, R. W. (ed.) Framing the

domains of IT management: Projecting the future

through the past. Cincinnati, OH: Pinnaflex Education

Resources.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From Transactional to

Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the

Vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18, 19-31.

Beer, M. & Nohria, N. (2000). Cracking the code of change.

Harvard Business Review, 78(3), 133-141.

Bernard, S. (2012). An Introduction To Enterprise

Architecture. Bloomington, IN, USA: AuthorHouse.

Bunge, M. (1966). Technology as Applied Science.

Technology and Culture, 7(3), 329-347.

Burnes, B. & James, H. (1995). Culture, cognitive

dissonance and the management of change.

International Journal of Operations & Production

Management, 15(8), 14-33.

Cannon-Bowers, J. A. & Salas, E. (2001). Reflections on

Shared Cognition. Journal of Organizational Behavior,

22(2), 195-202.

Carrillo, J., Cabrera, A., Román, C., Abad, M. & Jaramillo,

D. (2010). Roadmap for the implementation of an

enterprise architecture framework oriented to

institutions of higher education in Ecuador. In:

Software Technology and Engineering (ICSTE), 2010

2nd International Conference on, 2010. IEEE, V2-7-

V2-11.

CIO Council (2001). A Practical Guide to Federal

Enterprise Architecture. Available at http://www.cio.go

v/documents/bpeaguide.pdf.

Computer Economics. (2014). Enterprise Architecture

Adoption and Best Practices. April 2014. URL:

http://www.computereconomics.com/article.cfm?id=1

947 [Jan 21

st

2015].

Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W. & White, R. E. (1999). An

organizational learning framework: from intuition to

institution. Academy of management review, 522-537.

Davison, R. M., Martinsons, M. G. & N, K. (2004).

Principles of Canonical Action Research. Information

Systems Journal, 14(1), 65-86.

Dietz, J. L. G., Hoogervorst, J. A. P., Albani, A., Aveiro,

D., Babkin, E., Barjis, J., Caetano, A., Huysmans, P.,

Iijima, J., van Kervel, S. J. H., Mulder, H., Op ‘t Land,

M., Proper, H. A., Sanz, J., Terlouw, L., Tribolet, J.,

Verelst, J. & Winter, R. (2013). The discipline of

enterprise engineering. Int. J. Organisational Design

and Engineering, 3(1), 86-114.

Elving, W. J. L. (2005). The role of communication in

organisational change. Corporate Communications: An

International Journal, 10(2), 129-138.

Espinosa, J. A., Armour, F. & Boh, W. F. (2011). The Role

of Group Cognition in Enterprise Architecting. In:

System Sciences (HICSS), 2011 44th Hawaii

International Conference on, 4-7 Jan. 2011 2011. 1-10.

Fehskens, L. (2015). Len's Lens: Eight Ways We Frame

Our Concepts of Architecture. Journal of Enterprise

Architecture, 11(2), 55-59.

Finnish Ministry of Finance. (2011). Act on Information

Management Governance in Public Administration

(643/2011). URL: https://www.vm.fi/vm/en/04_public

ations_and_documents/03_documents/20110902Acton

I/Tietohallintolaki_englanniksi.pdf.

Finnish Ministry of Finance (2015). Tietoja valtion

tietohallinnosta 2014. Valtiovarainministeriön

julkaisuja 27/2015. Helsinki: Ministry of Finance.

Gartner. (2013). IT Glossary: Enterprise Architecture (EA).

URL: http://www.gartner.com/it-glossary/enterprise-

architecture-ea/ [21.02.2013].

Gregor, S., Hart, D. & Martin, N. (2007). Enterprise

architectures: enablers of business strategy and IS/IT

alignment in government. Information Technology &

People, 20(2), 96-120.

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

515

Hammer, M. & Champy, J. (1993). Reengineering the

corporation: a manifesto for business revolution.

London: Nicholas Brearly.

Hazen, B. T., Kung, L., Cegielski, C. G. & Jones-Farmer,

L. A. (2014). Performance expectancy and use of

enterprise architecture: training as an intervention.

Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 27(2),

6-6.

Hevner, A., March, S., Park, J. & Ram, S. (2004). Design

Science in Information Systems Research. MIS

Quarterly, 28(1), 75-106.

Hiekkanen, K., Korhonen, J. J., Collin, J., Patricio, E.,

Helenius, M. & Mykkanen, J. (2013). Architects'

Perceptions on EA Use -- An Empirical Study. In:

Business Informatics (CBI), 2013 IEEE 15th

Conference on, 15-18 July 2013 2013. 292-297.

Hjort-Madsen, K. (2006). Enterprise Architecture

Implementation and Management: A Case Study on

Interoperability. In: HICSS-39. Proceedings of the

39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on

System Sciences, 2006 Kauai, Hawaii, USA.

Holt, D. T., Armenakis, A. A., Feild, H. S. & Harris, S. G.

(2007). Readiness for Organizational Change: The

Systematic Development of a Scale. The Journal of

Applied Behavioral Science, 43(2), 232-255.

Houkes, W. N. (2013). Rules, Plans and the Normativity of

Technological Knowledge. In: de Vries, M. J.,

Hansson, S. O. & Meijers, A. W. M. (eds.) Norms in

Technology. Springer.

ISO/IEC/IEEE (2011). Systems and software engineering -

- Architecture description. ISO/IEC/IEEE

42010:2011(E) (Revision of ISO/IEC 42010:2007 and

IEEE Std 1471-2000).

Iyamu, T. (2009). The Factors Affecting Institutionalisation

of Enterprise Architecture in the Organisation. In:

Commerce and Enterprise Computing, 2009. CEC '09.

IEEE Conference on, 20-23 July 2009 2009. 221-225.

Iyamu, T. (2011). Enterprise Architecture as Information

Technology Strategy. In: Commerce and Enterprise

Computing (CEC), 2011 IEEE 13th Conference on, 5-

7 Sept. 2011 2011. 82-88.

Jones, R. A., Jimmieson, N. L. & Griffiths, A. (2005). The

Impact of Organizational Culture and Reshaping

Capabilities on Change Implementation Success: The

Mediating Role of Readiness for Change. Journal of

Management Studies, 42(2), 361-386.

Järvinen, P. (2015). On Design Research – Some Questions

and Answers. In: Matulevičius, R. & Dumas, M. (eds.)

Perspectives in Business Informatics Research.

Springer International Publishing.

Kaisler, H., Armour, F. & Valivullah, M. (2005). Enterprise

Architecting: Critical Problems. In: HICSS-38.

Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences, 2005 Waikoloa,

Hawaii, USA.

Kitchen, P. J. & Daly, F. (2002). Internal communication

during change management. Corporate

Communications: An International Journal, 7(1), 46-53.

Knowles, M. S. (1970). The Modern Practice of Adult

Education. New York: New York Association Press.

Koponen, E. (2009). The development, implementation and

use of e-learning: critical realism and design science

perspectives. Acta Electronica Universitatis

Tamperensis: 805. Tampere, Finland: University of

Tampere.

Kotter, J. P. (2008). A sense of urgency. Harvard Business

Press.

Lee, A. S. (2004). Thinking about Social Theory and

Philosophy for Information Systems. In: Mingers, J. &

Willcocks, L. (eds.) Social Theory and Philosophy for

Information Systems. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Lee, A. S. (2010). Retrospect and prospect: information

systems research in the last and next 25 years. Journal

of Information Technology, 25, 336-348.

Lee, A. S., Manoj, T. A. & Baskerville, R. L. (2015). Going

back to basics in design science: from the information

technology artifact to the information systems artifact.

Information Systems Journal, 2015(25), 5-21.

Lemmetti, J. & Pekkola, S. (2012). Understanding

Enterprise Architecture: Perceptions by the Finnish

Public Sector. In: Scholl, H., Janssen, M., Wimmer, M.,

Moe, C. & Flak, L. (eds.) Electronic Government.

Berlin: Springer.

Liu, Y. & Li, H. (2009). Applying Enterprise Architecture

in China E-Government: A Case of Implementing

Government-Led Credit Information System of Yiwu.

In: WHICEB2009. Eighth Wuhan International

Conference on E-Business, 2009 Wuhan, China. 538-

545.

Makiya, G. K. (2012). A multi-level investigation into the

antecedents of Enterprise Architecture (EA)

assimilation in the U.S. federal government: a

longitudinal mixed methods research study. 3530104

Ph.D., Case Western Reserve University.

March, S. T. & Smith, G. F. (1995). Design and natural

science research on information technology. Decision

Support Systems, 15(4), 251-266.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative Learning: Theory to

Practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing

Education, no. 74, 5-12.

Mezzanotte, D. M., Dehlinger, J. & Chakraborty, S. (2010).

On Applying the Theory of Structuration in Enterprise

Architecture Design. In: Computer and Information

Science (ICIS), 2010 IEEE/ACIS 9th International

Conference on, 18-20 Aug. 2010 2010. 859-863.

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B. & Lampel, J. (1998). Strategy

Safari: the Complete Guide Trough the Wilds of

Strategic Management. London: Financial Times

Prentice Hall.

Nassiff, E. (2012). Understanding the Value of Enterprise

Architecture for Organizations: A Grounded Theory

Approach. 3523496 Ph.D., Nova Southeastern

University.

North, E., North, J. & Benade, S. (2004). Information

Management and Enterprise Architecture Planning--A

Juxtaposition. Problems and Perspectives in

Management, (4), 166-179.

Oxford Dictionaries. (2010). Oxford Dictionaries. April

2010. URL: http://oxforddictionaries.com/ [Nov 18

th

2014].

ICEIS 2016 - 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

516

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A. &

Chatterjee, S. (2007). A Design Science Research

Methodology for Information Systems Research.

Journal of management information systems, 45-77.

Pehkonen, J. (2013). Early Phase Challenges and Solutions

in Enterprise Architecture of Public Sector. Master's

Degree Programme in Information and Knowledge

Management, Tampere University of Technology.

Päivärinta, T., Pekkola, S. & Moe, C. E. (2011). Grounding

Theory from Delphi Studies. Thirty Second

International Conference on Information Systems.

Shanghai.

Ross, J. W., Weill, P. & Robertson, D. C. (2006). Enterprise

architecture as strategy: Creating a foundation for

business execution. Boston, Massachusetts, USA:

Harvard Business School Press.

Schekkerman, J. (2005). Trends in Enterprise Architecture

2005: How are Organizations Progressing? Amersfoort,

Netherlands: Institute for Enterprise Architecture

Developments.

Schulman, J. (2003). Enterprise Architecture: Benefits and

Justification. URL: https://www.gartner.com/doc/3882

68/enterprise-architecture-benefits-justification.

Sembiring, J., Nuryatno, E. T. & Gondokaryono, Y. S.

(2011). Analyzing the Indicators and Requirements in

Main Components Of Enterprise Architecture

Methodology Development Using Grounded Theory in

Qualitative Methods. Society of Interdisciplinary

Business Research Conference. Bangkok.

Seppänen, V. (2014). From problems to critical success

factors of enterprise architecture adoption. Jyväskylä:

University of Jyväskylä.

Shupe, C. & Behling, R. (2006). Developing and

Implementing a Strategy for Technology Deployment.

Information Management Journal, 40(4), 52-57.

Skulmoski, G. J., Hartman, F. T. & Krahn, J. (2007). The

Delphi Method for Graduate Research. Journal of

Information Technology Education, 6(1), 1-21.

Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the Theory of Scales of

Measurement. Science, New Series, 103(2684), 677-

680.

Struijs, P., Camstra, A., Renssen, R. & Braaksma, B.

(2013). Redesign of Statistics Production within an

Architectural Framework: The Dutch Experience.

Journal of Official Statistics, 29(1), 49-71.

Syynimaa, N. (2013). Theoretical Perspectives of

Enterprise Architecture. 4th Nordic EA Summer School,

EASS 2013. Helsinki, Finland.

Syynimaa, N. (2015). Modelling the Resistance of

Enterprise Architecture Adoption: Linking Strategic

Level of Enterprise Architecture to Organisational

Changes and Change Resistance. In: Hammoudi, S.,

Maciaszek, L. & Teniente, E., eds. 17th International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS

2015), 2015 Barcelona, Spain. INSTICC, 143-153.

TOGAF (2009). TOGAF Version 9. Van Haren Publishing.

Vaishnavi, V. & Kuechler, B. (2013). Design Science

Research in Information Systems. URL: http://desrist.o

rg/desrist/.

Valtonen, K., Mäntynen, S., Leppänen, M. & Pulkkinen, M.

(2011). Enterprise Architecture Descriptions for

Enhancing Local Government Transformation and

Coherency Management: Case Study. In: Enterprise

Distributed Object Computing Conference Workshops

(EDOCW), 2011 15th IEEE International, Aug 29-Sep

2 2011. 360-369.

van Aken, J. E. (2004). Management Research Based on the

Paradigm of the Design Sciences: The Quest for Field-

Tested and Grounded Technological Rules. Journal of

Management Studies, 41(2), 219-246.

van de Ven, A. H. & Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining

Development and Change in Organizations. The

Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 510-540.

Washington, M. & Hacker, M. (2005). Why change fails:

knowledge counts. Leadership & Organization

Development Journal, 26(5), 400-411.

Vasilescu, C. (2012). General Enterprise Architecture

Concepts and the Benefits for an Organization. 7th

International Scientific Conference, Defence Resources

Management in the 21st Century. Braşov: Romanian

National Defence University, Regional Department of

Defence Resources Management Studies.

Venable, J., Pries-Heje, J. & Baskerville, R. (2012). A

Comprehensive Framework for Evaluation in Design

Science Research. In: Peffers, K., Rothenberger, M. &

Kuechler, B. (eds.) Design Science Research in

Information Systems. Advances in Theory and Practice.

Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B. & Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478.

Vera, D. & Crossan, M. (2004). Strategic Leadership and

Organizational Learning. The Academy of Management

Review, 29(2), 222-240.

Zachman, J. A. (1997). Enterprise architecture: The issue of

the century. Database Programming and Design, 10(3),

44-53.

Mitigating Enterprise Architecture Adoption Challenges - Improved EA Adoption Method

517