Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation in an

Online-coaching Application for Flexible Workers

Sophie Jent and Monique Janneck

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Applied Sciences, Mönkhofer Weg 239, Luebeck, Germany

Keywords: Gamification, Motivation, User Study.

Abstract: The number of people who are solo-self-employed or experience very flexible, individualized working

conditions has grown over the last years. As a consequence, these persons need to design their own working

conditions in the sense of ‘job crafting’. We are developing an online coaching application for this target

group to convey job design skills, increase well-being, and reduce stress. To enhance user motivation

gamification elements are used in the online coach. In this paper we report on the evaluation of a prototype

of the coaching application with different gamification elements by means of a user test with the target

group. The results show that gamification has only a small effect in short-term use, but seems promising in

the long term.

1 INTRODUCTION

The number of solo-self-employed and persons with

flexible, individualized working conditions – like

project work and home office – has grown over the

last years (Lohmann and Luber, 2004; Hill et al.,

1996). This also includes people who work while

traveling (BenMoussa, 2003). While flexible

working conditions offer many benefits, such as

increased job control, individual working hours and

possibly less work-family interference (Parslow et

al., 2004; Prottas and Thompson, 2006), workers

also face the challenge to design their own

workplace in a healthy and sustainable way. This

includes planning and setting working tasks,

designing the workplace ergonomically as well as

structuring their working times, breaks, and off-time.

Furthermore, people with individualized working

conditions (working at home or outwards) often

experience less social support from colleagues and

supervisors (Sturges, 2012; Paridon and Hupke,

2009). Thus, people in this target group need

comprehensive skills for job crafting (Bakker, 2010;

Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001) in order to work

efficiently and stay healthy (Tims and Bakker,

2010).

As part of a larger research project on flexible

working conditions we are currently developing an

online coaching application, the so-called ‘Job-

Crafting Coach’, for people with individualized

working conditions to convey job design skills,

increase well-being and reduce stress. A main

challenge in designing this application is to keep

user motivation high, since the target group typically

experiences high workloads and long working hours.

Gamification elements are often used in a non-

gaming context in order to improve user experience

and motivation (Detering et al., 2011a). Therefore,

in this paper we investigate whether and how

gamification elements can be used in this context to

enhance learning in a target group of mostly very

busy, adult users.

The paper is structured as follows: In the next

section we give an overview of related work and

discuss gamification elements with respect to our

special target group of highly skilled, flexible

workers. Based on this, a gamified prototype of the

coaching application was developed and tested with

the target group (sections 3 and 4.1). Results are

presented and discussed in sections 4.2 and 5.

2 RELATED WORK

Following a widely-used definition, gamification is

“the use of game design elements in non-game

contexts” with the goal of increasing motivation and

user activity (Detering et al., 2011b, p. 2). During

Jent, S. and Janneck, M.

Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation in an Online-coaching Application for Flexible Workers.

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2016) - Volume 2, pages 35-41

ISBN: 978-989-758-186-1

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

35

the last years the use of gamification in a large

variety of applications has increased (ibid.). Hamari

et al., (2014) reviewed 24 empirical studies on

gamification and examined its effects. The elements

mostly used in these studies were points,

leaderboards, and badges. Furthermore, progress

bars (Hamari et al., 2014), content unlocking (Iosup

and Epema, 2014) and countdowns (Corriero et al.,

2014) are often utilized for gamification.

Points are a basic game component (Nah et al.,

2013). Users collect points as they make progress

with their tasks.

Leaderboards are ranking systems, in which all

users are listed according to their scores (e.g.,

points collected). Therefore, leaderboards add a

social component and invoke a sense of

competition (Kapp, 2012).

Badges are awards that users get for certain

achievements, representing success. Users are

motivated to collect further ‘trophies’ (Kumar,

2013).

Progress bars show to what extent a task is

carried out and represent positive development

(Neeli, 2012).

Content unlocking means that the player gains

access to content or functionality according to

certain rules, e.g. after prior tasks were fulfilled.

Countdowns limit the time in which tasks must

be completed, thus implementing time pressure

as a game design factor (Hsu et al., 2013).

In the 24 studies reviewed by Hamari et al. (2014),

psychological outcomes (e.g., motivation, enjoyment

and attitude) as well as behavioral outcomes (e.g.,

effectiveness of learning) were investigated. The

results show that gamification may have a positive

effect on both psychological and behavioral

variables, but this depends very much on the context

and the characteristics of the users.

Education/learning is the biggest application field

for using gamification, followed by intra-

organizational and work-related systems (Hamari et

al., 2014).

Regarding work contexts, participation and

steering behavior on a question and answer website

were influences positively by gamification

(Anderson et al., 2013; Hamari et al., 2014).

Furthermore, in a crowdsourcing project the quality

of completed tasks, task completion speed and

motivation to complete tasks were enhanced

(Eickhoff et al., 2012; Hamari et al., 2014).

Regarding education and learning mostly

students were surveyed (Denny, 2013; Cheong et al.,

2013; Dominguez et al., 2013; Zachary et al., 2011;

Halan et al., 2010). A broad range of gamification

elements was used in this context. Positive effects

reported in these studies include increased

motivation, commitment, and enjoyment of learning

tasks (Hamari et al., 2014).

Denny (2013) investigated the use of badges in

an online learning tool (including question and

answer forums). He split-randomized a class (>1000

students) into two groups. The members of the first

group were able to get badges for their activity and

contributions in the online learning tool, whereas the

members of the other group had no access to the

badge system. After four weeks the first group (with

badges) answered more questions, had used the tool

more often and enjoyed being able to collect badges.

The number of authored questions was not affected.

In another study two groups of medical students

were supposed to train their interviewing and

interpersonal skills by means of virtual patients in a

web-based application. The first group used an

application with gamification elements like

leaderboards, narratives, und countdowns, while the

second group used the same tool without these

elements. In the first group, user participation

increased (Halan et al., 2010).

3 PROTOTYPICAL

IMPLEMENTATION

In this section we present a prototype of the Job-

Crafting Coach, which incorporates several

gamification elements in order to test their

usefulness with the target group of highly skilled,

adult users.

As described in the previous section, in former

studies mostly students were the subjects to

investigate the effects of gamification in learning

contexts. Students are somewhat similar to our target

group when it comes to self-organizing one’s

learning environment (e.g. doing project work,

scheduling times for individual learning, breaks and

off-time). Therefore, we assume that gamification

elements that were successfully used in

education/learning contexts may also be suitable for

our target group. However, our coaching application

is targeted at different age groups: Presumably,

especially older persons might be less attracted to

games. Therefore, the suitability of different

gamification elements needs to be established.

The Job-Crafting Coach consists of three

sections: In the first section job crafting facts and

knowledge are presented mainly in the form of short

animated videos. In the second section,

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

36

corresponding trainings and exercises are offered

based on a self-assessment of one’s working

situation and current challenges, strengths and

weaknesses. Sample exercises include hints on how

to design a home office or mobile workplace

ergonomically, a task planning exercise, trainings on

how to do proper networking, relaxation exercises,

and trainings focusing on a better work-life balance.

In the third section users learn to set goals and

integrate the exercises and strategies they learned

into their everyday life.

The following gamification elements were

considered:

Assignment of points and badges to users who

completed certain exercises or achieved goals

they set for themselves, respectively.

Furthermore, badges might show how often

(‘comeback badge’) or how many days in a row

(‘day in a row badge’) the user has logged in.

Using the content unlocking principle by

activating certain exercises only after the users

performed other actions.

Progress bars and a leaderboard, the latter to

stimulate competition.

Furthermore, the following elements were used to

enhance motivation:

Playful quizzes designed as single or multi-player

games to check the users’ knowledge.

A rating system (using stars) to evaluate the

exercises.

A ‘tip of the day’ to stimulate interest and

curiosity.

Countdowns were not used, as many exercises need

time and patience and the users should not feel

stressed.

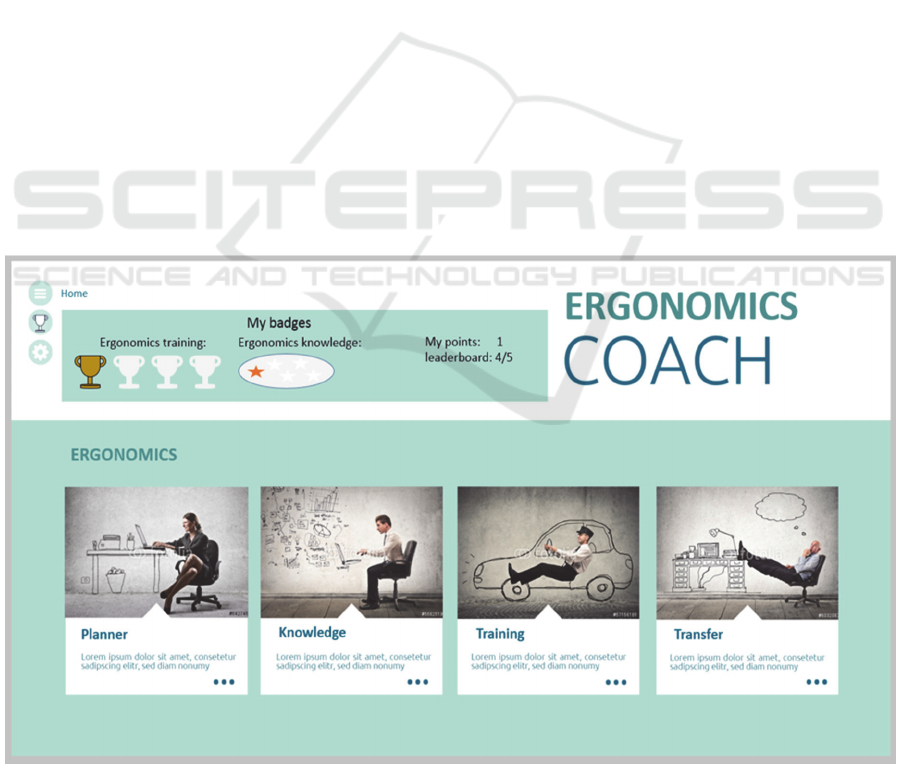

For evaluation purposes we tested several

ergonomics-related exercises of the Job-Crafting

Coach (e.g. an eye relaxation exercise, see figure 1).

It includes badges, points, a progress bar, rewards in

the form of unlocking content (activation of

exercises) and a leaderboard. Furthermore, the

prototype provides a ‘tip of the day’ and a star rating

system for the exercises.

4 EVALUATION

4.1 Methods

We conducted user tests of the Job-Crafting Coach

with 16 test persons belonging to the target group (7

female, 9 male). Mean age was 35.9 years (range:

28-60 years).

The evaluation consisted of two parts. In the first

part (20 minutes) the participants were asked to

work through the knowledge units and complete

Figure 1: Prototype showing badges, points and position in leaderboard.

Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation in an Online-coaching Application for Flexible Workers

37

Figure 2: Eye exercise with progress bar.

several exercises (eye exercise, see figure 2, and

neck relaxation exercise). All participants started

with no badges, no points and on the last place in the

leaderboard and continually acquired points and

badges for each completed task. According to the

score the user raised in the leaderboard. For every

completed exercise, a new exercise was unlocked.

At the beginning of each test, two exercises were

already available.

In the second part the participants were asked to

fill out a questionnaire concerning their general

gaming behaviour, their motivation during the test

run and their evaluation of the gamification elements

provided.

4.2 Results

General Gaming Behaviour. Two of the participants

play mobile and/or PC games daily, two several

times a week, six occasionally (less than several

times a week) and six never. One person specifies

that he plays mobile and/or PC games with others

together daily, two several times a week and 13

never. Board games are played by two of the

participants several times a week, by four several

times a month and by 10 occasionally (less than

several times a month).

Motivation during User Tests. The testers were

asked to evaluate how much they fell motivated by

the following gamification elements during the test:

badges, progress bar, points and leaderboard (table

1). The participants were able to choose between

‘very motivated’, ‘somewhat motivated’, ‘hardly

motivated’, ‘not motivated’ and ‘I haven’t noticed’.

The participants who chose ‘I haven’t noticed’

indicated that they focused too much on the task and

therefore did not pay attention to the gamification

elements. Some of the persons who felt ‘somewhat

motivated’ stated that the test was actually too short

to invoke motivation but that the elements might

motivate them in the long run.

Table 1: User motivation during the tests.

How much were you

motivated by …?

very

motivated

somewhat

motivated

hardly motivated not motivated I haven’t noticed

badges 2 6 6 1 1

progress bar 6 5 1 2 2

points 0 7 3 1 5

leaderboard 1 4 6 4 1

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

38

Table 2: Long-term user motivation.

How much would you be motivated by …? very motivated somewhat motivated hardly motivated not motivated

badges 3 10 3 0

progress bar 7 8 0 1

points 4 9 2 1

leaderboard 2 8 3 3

tip of the day 1 5 7 3

comeback badge 1 7 7 1

days in a row badge 1 8 3 4

activation of exercises 8 5 2 1

Table 3: Long-term user motivation of female and male participants (percentages rounded).

How much would

you feel motivated

by …?

very motivated somewhat motivated hardly motivated not motivated

female male female male female male female male

badges 14% 22% 43% 78% 43% 0% 0% 0%

progress bar 29% 56% 71% 33% 0% 0% 0% 11%

points 14% 33% 57% 56% 29% 0% 0% 11%

leaderboard 0% 22% 57% 44% 14% 22% 29% 11%

tip of the day 14% 0% 29% 33% 43% 44% 14% 22%

comeback badge 0% 11% 14% 67% 86% 11% 0% 11%

days in a row badge 0% 11% 14% 78% 43% 0% 43% 11%

activation of

exercises

57% 44% 29% 33% 0% 22% 14% 0%

Long-term Motivation. The participants were also

asked to estimate to what extent the gamification

elements would enhance their long-term motivation

(table 2).

They were also asked to assess further elements

not present in the prototype. Regarding quizzes,

three of the participants said that a quiz that retrieves

knowledge playfully would make lots of fun, 10

some fun, two little fun and one no fun.

Furthermore, four participants said that a quiz would

motivate them very much to work through further

knowledge units, nine a little, two barely and one not

at all.

14 of the 16 participants would like to use a star

rating system to evaluate the exercises. Eight

persons said that such a rating system, showing

reviews from others, would be very helpful, five a

little helpful and three hardly helpful. Seven of the

participants would find it very interesting to see such

reviews, another seven a little interesting and two

hardly interesting. However, in the user tests the

rating of the exercises had little influence on the

participants’ choices: 11 participants said the ratings

had no influence, three said some influence and two

a little influence. Instead, the topics of the exercises

were the decisive factor. However, as the full

version of the Job-Crafting Coach will comprise a

lot more content, a rating system will presumably

gain importance.

The distribution of responses of female and male

participants is shown in table 3.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this study we investigated how solo-self-

employed and people with individualized working

conditions could be motivated to use an online

coaching application by means of gamification.

We examined gamification elements and other

additions (‘tip of the day’, quizzes and a star rating

system) as motivational drivers. To this end, we

developed a prototype and tested it with the target

group.

The results indicate that progress bars, activation

of exercises, badges and points would generate the

most positive motivational effects in the long term.

A leaderboard would achieve a less positive effect.

Furthermore, the participants would also feel

Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation in an Online-coaching Application for Flexible Workers

39

motivated by quizzes and a star rating system for the

exercises.

The ‘tip of the day’, ‘days in a row badge’ and

‘comeback badge’ were rated the least positive. This

shows that the type of badges is very important and

that different badges might not have the same

motivational effects (see table 2). This should be

investigated further in future studies.

The results also show that gamification elements

have different effects on female and male

participants: Male users would feel more motivated

by points and badges (particularly ‘days in a row

badge’ and ‘comeback badge’) than female

participants.

Our study also shows that gamification has only

a small effect in short-term use compared to long-

term use. Only progress bars seem to motivate

similarly regarding temporary and long-term use.

This is promising as our application is specifically

geared at long-term usage, and gamification

elements are supposed to support continual use and

keep up participants’ motivation in spite of a

stressful working life. However, general research on

gamification should consider that short-term and

long-term effects might be quite different. Thus,

gamification might be less suitable in applications

that are typically only used for shorter periods of

time. Further studies on gamification need to take

this into account.

Interestingly, the testers’ general gaming

behaviour had no influence on the results. However,

it is known from previous studies that user

characteristics influence the effectiveness of

gamification (cf. Hamari et al., 2014). Therefore, in

our future research we will take a closer look at

different personal variables such as age and also

personality traits.

Our target group differs from the students

usually investigated within educational and learning

contexts in previous work (Hamari et al., 2014).

However, we argued that both groups share

significant similarities. Our study confirms that the

positive effects of gamification carry over to our

target group of professionals with flexible working

conditions.

Of course an important limitation of this study is

its small sample size, as it was meant as a first test

whether gamification makes sense in this context at

all. Based on these first results, a fully functional

prototype will be developed incorporating the

elements that proved successful in this test (progress

bars, activation of exercises, badges, points,

leaderboard, quizzes and star rating) to test their

long-term effects with a large set of users.

REFERENCES

Anderson, A. et al., 2013. Steering user behavior with

badges, Proceedings of the 22nd international

conference on World Wide Web, 95-106.

Bakker, A., 2010. Engagement and “job crafting”:

engaged employees create their own great place to

work. In S. L. Albrecht (Hrsg.), Handbook of

employee engagement: Perspectives, issues, research

and practice, S. 229-244.

BenMoussa, C., 2003. Workers on the move: New

opportunities through mobile commerce, Stockholm

mobility roundtable, 22-23.

Cheong, C. et al., 2013. Quick Quiz: A Gamified

Approach for Enhancing Learning, PACIS.

Corriero, N. et al., 2014. Simulations of clinical cases for

learning in e-health, International Journal of

Information and Education Technology.

Denny, P., 2013. The effect of virtual achievements on

student engagement, Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

ACM.

Detering, S. et al., 2011a. Gamification. using game-

design elements in non-gaming contexts, CHI'11

Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing

Systems. ACM.

Detering, S. et al., 2011b. From game design elements to

gamefulness: defining gamification, Proceedings of

the 15th International Academic MindTrek

Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments.

ACM.

Domínguez, A. et al., 2013. Gamifying learning

experiences: Practical implications and outcomes,

Computers & Education 63, 380-392.

Eickhoff, C. et al., 2012. Quality through flow and

immersion: gamifying crowdsourced relevance

assessments, Proceedings of the 35th international

ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development

in information retrieval. ACM.

Halan, S. et al., 2010. High Score!-Motivation Strategies

for User Participation in Virtual Human Development,

Intelligent Virtual Agents, Springer, Berlin

Heidelberg.

Hamari, J. et al., 2014. Does gamification work? - A

literature review of empirical studies on gamification,

47th Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences (HICSS).

Hill, E. et al., 1996. Work and family in the virtual office:

Perceived influences of mobile telework, Family

relations, 293-301.

Hsu, S. H. et al., 2013. Designing attractive gamification

features for collaborative storytelling websites,

Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 16

(6), 428-435.

Iosup, A., Epema, D., 2014. An experience report on using

gamification in technical higher education,

Proceedings of the 45th ACM technical symposium on

Computer science education. ACM.

Kapp, K. M., 2012. The gamification of learning and

instruction: game-based methods and strategies for

WEBIST 2016 - 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

40

training and education, John Wiley & Sons.

Kumar, J., 2013. Gamification at work: designing

engaging business software, Springer, Berlin

Heidelberg.

Lohmann, H., Luber, S., 2004. Trends in self-employment

in Germany: different types, different developments.

The Reemergence of Self-Employment. A comparative

study of self-employment dynamics and social

inequality, 36-74.

Nah, F. et al., 2013. Gamification of education using

computer games. Human Interface and the

Management of Information. Information and

Interaction for Learning, Culture, Collaboration and

Business, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg.

Neeli, B. K., 2012. A method to engage employees using

gamification in BPO industry, Third International

Conference on Services in Emerging Markets

(ICSEM). IEEE.

Paridon, H., Hupke, M., 2009. Psychosocial Impact of

Mobile Telework: Results from an Online Survey.

Europe’s Journal of Psychology 5 (1).

Parslow, R.A. et al., 2004. The associations between work

stress and mental health: A comparison of

organizationally employed and self-employed

workers. Work & Stress 18 (3), 231-244.

Prottas, D. J., Thompson, C. A., 2006. Stress, satisfaction,

and the work-family interface: A comparison of self-

employed business owners, independents, and

organizational employees. Journal of Occupational

Health Psychology 11 (4), 100-118.

Sturges, J., 2012. Crafting a balance between work and

home. Human Relations 65 (12), 1539-1559.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., 2010. Job crafting: Towards a

new model of individual job redesign. Journal of

Industrial Psychology 36 (2), 1-9.

Wrzesniewski, A., Dutton, J. E., 2001. Crafting a Job:

Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their

Work. Academy of Management Review 26 (2), 179–

201.

Zachary, F. et al., 2011. Orientation passport: using

gamification to engage university students,

Proceedings of the 23rd Australian Computer-Human

Interaction Conference. ACM.

Using Gamification to Enhance User Motivation in an Online-coaching Application for Flexible Workers

41