Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data

Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s

Development

Robert Olszewski

1

, Agnieszka Turek

1

and Marcin Łączyński

2

1

Faculty of Geodesy and Cartography, Warsaw University of Technology, Pl. Politechniki 1, Warsaw, Poland

2

Laboratory of Media Studies, University of Warsaw, ul. Bednarska 2/4, Warsaw, Poland

Keywords: Spatial Data Mining, Gamification, Data Analysis, Participatory Modelling, Revitalisation, Smart City.

Abstract: The basic problem in predictive participatory urban planning is activating residents of a city, e.g. through the

application of the technique of individual and/or team gamification. The authors of the article developed (and

tested in Płock) a methodology and prototype of an urban game called “Urban Shaper”. This permitted

obtaining a vast collection of opinions of participants on the directions of potential development of the city.

The opinions, however, are expressed in an indirect manner. Therefore, their analysis and modelling of

participatory urban development requires the application of extended algorithms of spatial statistics. The

collected source data are successively processed by means of spatial data mining techniques, permitting

activation of condensed spatial knowledge based on “raw” source data with high volume (big data).

1 INTRODUCTION

In modern times, access to data (including spatial

data) has become relatively easy. “Raw” data,

however, require transformation into useful

information, and then into applicable knowledge and

skills of decision making based on the obtained

analysis results. Activation of knowledge based on

available information (also spatial information) is

therefore of key importance in the epoch in which

factories have ceased to be the places generating

economic value, and media and teleinformation

networks have become such places.The approach

proposed by the authors combines the possibilities of

GIS packages and statistical software. It permits the

performance of very complex analyses. One of the

methods of such an analysis is the application of so-

called data mining and data enrichment for the

detection of patterns, rules, and structures “hidden” in

the data base. Source data, e.g. location of objects in

the geographic space and attributes describing them

are almost commonly available. The determination of

temporal-spatial correlations, key factors determining

changes, or the spatial scale of their effect, however,

require the transformation of “raw” data into

information.

The authors used spatial data mining techniques

to analyze the data collected for the city of Płock

(with 100 thousand residents), in order to identify

significant phenomena and problems occurring in the

city.

2 INFRASTRUCTURE AND

SOCIAL PROBLEMS OF

PŁOCK

Płock is a city located in the Mazowieckie

Voivodship, approximately 115 km west of Warsaw,

the capital of Poland. The city has a population of

approximately 125 thousand over an area of 88 km

2

.

In administrative terns, Płock is divided into 23

districts, including 21 residential districts, and two

uninhabited industrial districts.

In the scope of revitalisation activities, the city

authorities identified crisis areas with concentration

of negative social phenomena, as well as economic,

spatial-functional, technical, or environmental issues.

The areas are also distinguished by an insufficient

level of social participation and participation of

residents in the public and cultural life of the city. In

2014, the Municipal Office of Płock conducted a

176

Olszewski, R., Turek, A. and Ł ˛aczy

´

nski, M.

Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0006005201760181

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Data Management Technologies and Applications (DATA 2016), pages 176-181

ISBN: 978-989-758-193-9

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

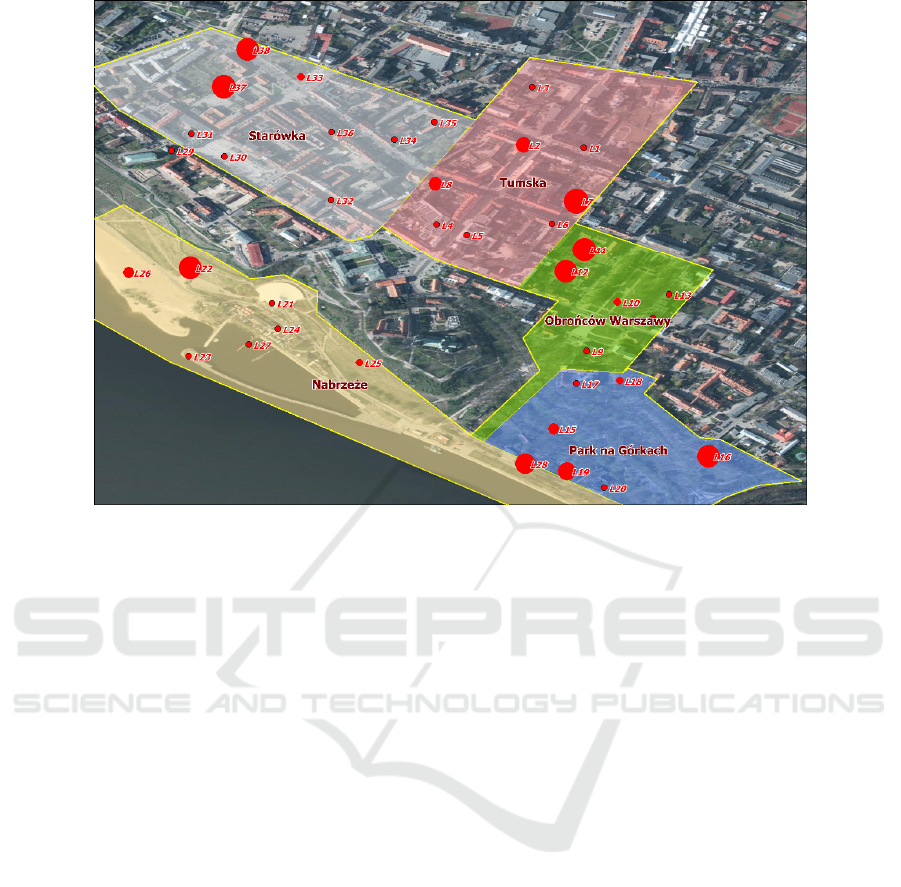

Figure 1: Study area divided into 5 parts with 38 points of interest.

survey providing answers of 1904 respondents. In

each of the designated areas, the following groups of

problems were defined: technical problems, social

problems related to the quality of life of residents, and

problems concerning lack of certain forms of activity

near the place of residence. Residents also identified

areas requiring revitalisation. The results of the

survey permitted preliminary verification of the main

problems occurring in the selected part of Płock. For

example, residents of the city centre (Old Town

district) point out lack of places permitting various

types of activity near their place of residence. The

analysed area lacks places for spending free time (e.g.

local club, internet café, library, fitness club,

community centre) or events integrating the local

community. Based on this information, the authors of

the article selected an area located in the city centre

for the analysis. The area was divided into five sub-

areas differing in terms of main problems and barriers

for local development. A total of 38 objects of public

utility, parks, tenement houses, etc. evoking strong

emotions in the residents of Płock were also identified

in the area (Fig.1). The size of the pie chart represents

the varied level of activity of the game participants in

reference to particular objects in five selected areas of

the city.

The following priority problems were identified

for the designated areas:

Area 1 - "Tumska" – problem of the renovated

Tumska Street (promenade) which contrary to the

assumptions did not become attractive for the

residents and new tenants;

Area 2 - "Obrońców Warszawy" (Warsaw Defenders’

Square) – low standard of public space;

Area 3 - "Park na Górkach" – degraded green areas in

the city centre;

Area 4 - "Nabrzeże" - problem of connectivity of the

city with the river, low standard of public space;

Area 5 - "Starówka" (Old Town) - low standard of

building development, depopulation of the area.

The identification of the primary problems of the

city requires appropriate analysis of collected data. In

order to transform passive and atomized individuals

into open (geo)information society developing a

vision of development of the city in the process of

social participation, it is crucial to reach the emotions

of the citizens, and to release their social energy. The

opinions of the residents are valuable for further

actions. One of the most effective (and most

enjoyable) way to achieve such an effect is so-called

gamification, i.e. encouraging the participants to take

part in the mass “game” involving mobile

applications, advanced technologies applying e.g.

computer game engines, and elements of augmented

reality.

In order to convince the city residents to express

their opinions on potential directions of development

of the city and its revitalisation, the authors developed

a methodology and prototype of an urban game called

“Urban Shaper”. Tests of the game conducted on a

Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development

177

group of approximately 250 residents of Płock

permitted obtaining a set of spatially distributed

source data. The opinions of the residents, however,

are expressed in an indirect way. Therefore, their

analysis and modelling of the participatory process of

the city‘s development requires the application of

extended algorithms of spatial statistics.

2.1 Gamification in Collecting Spatial

Information

For the purpose of increasing the involvement of

recipients in the designed platform for collection of

information regarding urban space, our team referred

to solutions based on gamification defined as “the use

of the mechanics and aesthetics of games and game

thinking to increase the involvement of people,

motivate action, and promote learning and problem

solving training” (Kapp, 2012). Gamification is a

relatively new trend emerging from deliberations of

several researchers dealing with the effect of games

on the life and behaviour of people, as well as from

practical experiences of companies using gaming

mechanisms to determine the behaviours of their

employees (Clark, 2009; McGonigal, 2011;

Zichermann, 2013; Robson et al., 2015). The key

features of the approach include (Kapp, 2012):

• Development of a system with features of a game,

aimed at involving participants in an activity

based on a system of rules, goals, interactions,

feedbacks, and measureable score system;

• Use of particular mechanisms typical of games

such as points, levels, score, or time limits for the

performance of particular tasks;

• Development of a coherent plot and aesthetics

characteristic of a game;

• Generating a playful approach to the activity in

participants, leading to an increase in internal

motivation for action;

• Focusing on the subject of the game, and increase

in emotional involvement for better memorisation

of new content, and faster learning in such an

environment;

• Development of a clear motivational system for

participants;

Both the source data collected in the process of

gamification and the resulting information are of

georeferential character – they refer to a particular

place in space, and are differentiated in such space.

Therefore, their analysis requires the application of

spatial data mining techniques, and the visualisation of

results – a map (Goodchild, 2007; Gąsiorowski,

Hajkowska, Olszewski, 2015). The application of

modern advanced information-communication

technologies permits fast obtaining of information

resources of big data type. Their exploration, however,

requires the use of a map (Fiedukowicz, 2013). Owing

to the applied approach, large sets of spatial data are

subject to interpretation, generalisation, and

aggregation, leading to the development of a map as a

medium of transfer of legible spatial information.

Research in the field of gamification, and

knowledge acquisition from spatial data bases

(Piatetsky-Shapiro, Frawley, 1991) are parts of the

broadly defined concept of a smart city (Opromolla,

2015; Uskov, Sekar, 2015; Cecchini, 2015).

2.2 Game “Urban Shaper”

Game “Urban Shaper” is a network application

developed in PHP language, adjusted to be used

during workshops and discussions with residents.

Data collected during the game are saved in the form

of XLS spreadsheets, and exported during post-

processing to a data mining system permitting their

more thorough analysis.

The game has an implemented functionality of

supporting real maps with marked points (buildings,

areas) which the described problems and activities

conducted by the participants concern.

Each team of 20-25 persons is divided into five

groups of 4-5 persons. Each group receives

information concerning their district/area of the city,

demonstrating the state of buildings and places

covered by the activities of the team, as well as

problems occurring in such places. Each place and

problem is described by means of five parameters:

public services, recreation, commercial services,

technical state, and tourist values.

Based on the awarded virtual “budget”, the

participants perform activities involving the elimination

of particular problems (e.g. repair of broken lighting,

repair of road surface, replacing heating systems in

municipal buildings), or introduction of positive

changes by adding new functions to particular areas (e.g.

assembly of a playground, opening a community centre

for residents).

The game can also be used as a tool for collecting

geoinformation data during workshops as a part of the

social consultations process.

The categories of information collected during the

game include:

• buildings and areas attracting the attention of the

participants to the highest degree;

• the most frequently selected revitalisation

activities;

• problems most frequently pointed out by the

participants as requiring close attention;

DATA 2016 - 5th International Conference on Data Management Technologies and Applications

178

• differentiation of the strategy of spatial

management depending on the area of the city;

• key functions ascribed by residents to particular

areas;

The game offers a possibility of choice of a score

system in a round in which the tool itself implements

specified persuasion goals which can include:

• presentation of the most cost-effective

revitalisation strategies;

• incentive for the development of strategies

responding to specific objective problems of a

given area (e.g. low availability of public services

or recreational areas);

• generating interest in a specific area of the city or

a specific category of activities, usually omitted

by residents in proposals of corrective actions;

The selection of areas, problems, and information

on potential revitalisation activities can be done in

several ways.

Firstly, the information can be provided by the

institutions of the city ordering conducting the

workshops based on data available to public offices –

e.g. information on the technical state of buildings,

amounts of rent, purpose of particular areas, and

information on social problems in particular parts of

the city (e.g. from an institution of social welfare or

the Police).

Another way of collection of the information (such

a system was applied during the implementation of the

pilot project in Płock) is the use of the existing results

of surveys concerning opinions of residents regarding

the revitalisation of the city, or conducting a mini

survey on the subject. Such a survey can be of

qualitative character, and has to be conducted based on

a representative sample of residents – its exclusive

objective is to obtain possibly the broadest range of

proposals of places and problems that should be

included in the game, without the necessity of

estimation of their quantitative importance.

The approach of the Authors is not the only such

solution in the world (more examples are described

on websites: www.urbaninteraction.net/city-gaming/,

www.blog.eai.eu/serious-games-in-sustainable-urba

n-development-part-1/). However the majority of

existing games do not work on current spatial data,

and they are not used as a tool of public consultation

and social participation.

3 RESULTS OF THE PILOT

GAME IN PŁOCK

The developed urban game methodology was tested

on 15 April 2016 in Płock during the pilot game

jointly implemented by team “Coniuncta” and the

Municipal Office of Płock under the auspices of the

International Training Centre for Authorities/Local

Entities (CIFAL - Centre International de Formation

des Autorites/Acteurs Locaux) of the United Nations

Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). The

study involved the participation of more than 160

high school students aged 16-18.

Data collected during the pilot game were

additionally enriched by attribute-spatial information

obtained from the topographic data base and

municipal registers, e.g. several thousand sale-

purchase transactions permitted the development of a

map of differentiation of real estate prices in Płock.

The use of topographic data permitted the

determination of distances from particular schools to

38 objects constituting elements of the urban game,

because the level of interest of the participants in the

technical state of such objects was very diverse. On

the map (Fig. 1), the size of the pie chart represented

the varied level of activity of the game participants in

reference to particular objects in five selected areas of

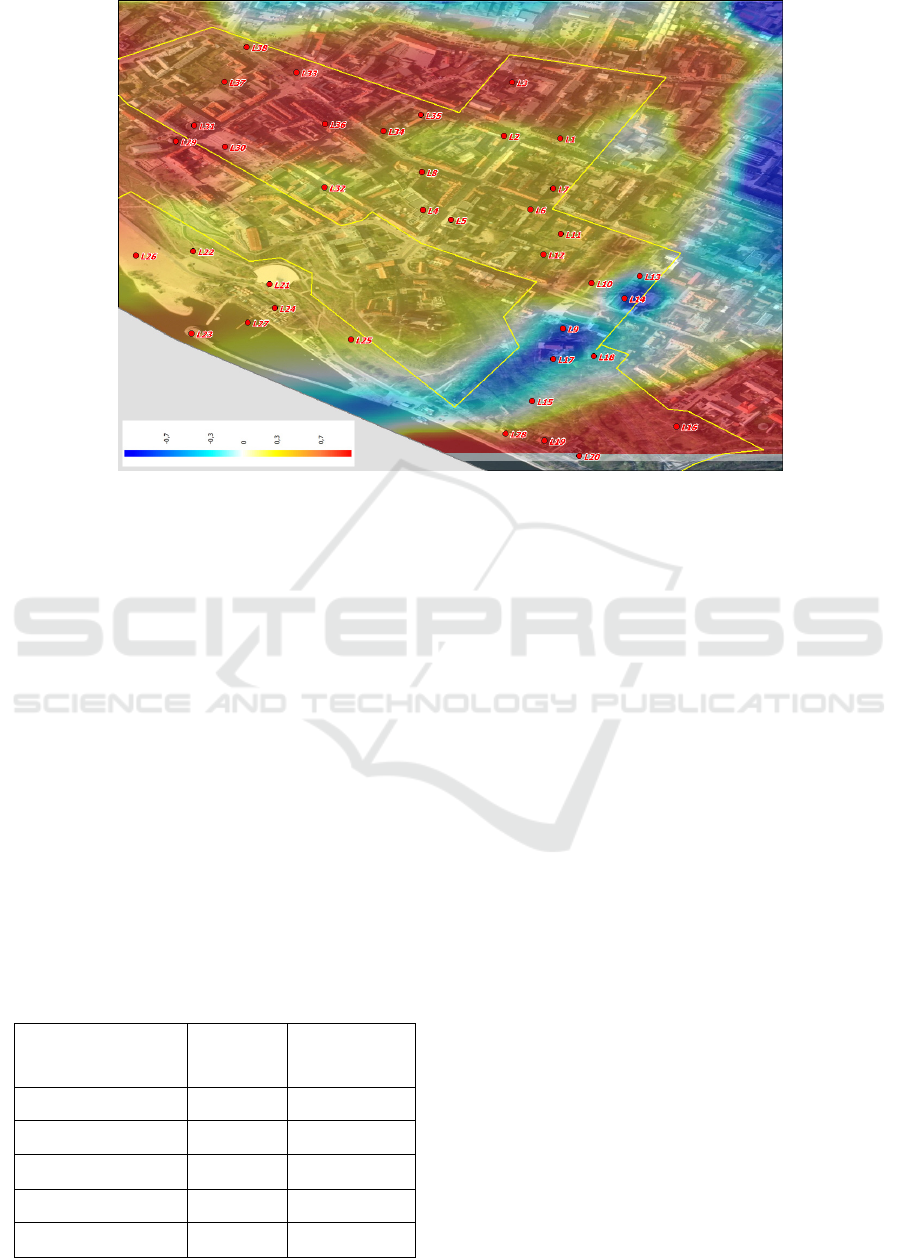

the city. The determination of the Pearson’s

correlation between real estate prices in a given area

of the city and the level of interest of participants (Fig.

2) shows quite strong positive correlation between the

factors for the Old Town area. In the southern

districts: “Obrońców Warszawy” and “Park na

Górkach”, a negative correlation occurs.

Based on spatial predicators determined based on

topographic correlations in the data analyses, such as

distance from the school of a given student to points

L1-L38, as well as the methodology of forming

association rules, the authors proposed the following

research hypothesis: “The objects of interest of young

residents of Płock are public purpose objects located

within a distance of not more than 600 m from their

school (up to 600 m)”. This permits the development

of the following fuzzy rule: “young citizens of the city

are interested in public spaces located in the vicinity

of the place of their education”.

Similar patterns of data mining were prepared for

a holistic analysis of data collected in the course of

the game, and general geographic and thematic data

collected in the city registers with the application of

decision making trees and other methods of machine

learning (Fayyad, 1996; Cabena, 1998; Han, Kamber,

2000; Hand, 2001; Miller, Han, 2001; Witten, Frank,

2005; Nisbet, 2009; Fiedukowicz, Gąsiorowski,

Olszewski, 2015). After performing the experiment in

the majority of schools in the city, the collected data

will be thoroughly analysed with the application of

such techniques.

Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development

179

Figure 2: Pearson’s correlation between real estate prices and the level of interest of participants.

Example data for area 1 “Tumska Street”

concerning effects of decisions made by the

participants are presented in the table 1. Point values

expressed as the mean and standard deviation permit

the determination of the priorities of revitalisation

activities, as well as differentiation of decision

making strategies adopted by the participants. The

observed focus is on recreation and tourist functions

of the analysed area, whereas for tourist values, the

standard deviation is considerably higher, suggesting

lower coherence of decisions in the scope. Low mean

and low differentiation of decisions concerns

technical state. This suggests that it is not treated as

an important issue in the analysed sample of

participants of the pilot game in the case of area

“Tumska Street” (it can be e.g. a derivative of the

actual best technical state of buildings in the area, also

evident in the parameters of the location in the game).

Table 1: Decision results for area 1 "Tumska Street".

Area of effect

Progress

mean

Progress

standard

deviation

public services 6.14 1.95

recreation 10.00 1.29

commercial services 5.29 1.80

technical state 5.57 0.98

tourist values 9.29 1.80

4 SUMMARY AND FUTURE

PLANS

The results of the pilot game “Urban Shaper”

conducted in Płock suggest a number of advantages

of this form of activity from the point of view of

obtaining information from city residents. The most

important advantages observed in the course of the

pilot game include:

• the possibility of obtaining opinions from a large

group of residents at the same time in the course

of a relatively short workshop;

• in addition to obtaining information, the game

also offers educational values – it familiarises the

participating residents with the basic terms in the

scope of spatial planning. It can also constitute a

starting point for a substantive discussion on

problems faced by particular areas of the city, and

optimum revitalisation strategies;

The choice of any setting of the game parameters

permits using the game for both obtaining

information (in this case the game does not award

score to any specific revitalisation strategy), and for

educational-persuasion purposes (Bogost, 2010) (in

this variant, the game may assume specific

preferences for particular models of revitalisation

activities, e.g. energy-efficient, cost-efficient, or in

accordance with the city’s strategy).

DATA 2016 - 5th International Conference on Data Management Technologies and Applications

180

The performed research employed exceptionally

simple spatially located data available on the Google

Maps website in the form of a “classic” map and

ortoimage from satellite photographs. The intention

of the authors is the expansion of the concept of the

research in project FabSpace 2.0 “The Fablab for

geodata-driven innovation – by leveraging Space

data in particular, in Universities 2.0” currently

implemented in the scope of programme Horizon

2020, by the application of more sophisticated

sources of spatial information, e.g. satellite images

SPOT 5 (spatial resolution of photographs 2.5 m-5 m)

and SPOT 6-7 (pixel 1.5 m-3 m). The aforementioned

systems register the panchromatic scope and near

infrared. This permits the development of a

composition in natural colours, and e.g. so-called

standard composition. On the map, vegetation is

represented by red colour, and is very legible.

Satellite background defined in such a way can be

used in a variant of the game dedicated to the issues

of environmental protection, analysis of development

of green areas, etc.

The presented issues are at the very preliminary

stage of research. The authors plan to conduct the

game at a massive scale in order to collect big data for

many cities. The proposed (and many others)

analytical schemes will be applied and improved.

The currently developed version of the game

dedicated for mobile devices will be tested in several

selected European cities. This will permit the analysis

of spatial big data considering the cultural, economic,

and social differences between residents of cities in

different countries of the European Union.

REFERENCES

Kapp, K. M., 2012. The Gamification of Learning and

Instruction: Game-based Methods and Strategies for

Training and Education.

McGonigal J., 2011. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make

Us Better and How They Can Change the World.

Zichermann G., 2013. The Gamification Revolution: How

Leaders Leverage Game Mechanics to Crush the

Competition.

Alfrink, K. 2014. “The Gameful City.” in: The Gameful

World, edited by Steffen P. Walz and Sebastian

Deterding, 34. London, UK: MIT Press.

Robson, K., Plangger, K., Kietzmann, J., McCarthy, I. &

Pitt, L., 2015. "Is it all a game? Understanding the

principles of gamification". Business Horizons 58 (4):

411–420.

Bogost, I., 2010. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power

of Videogames, MIT Press.

Opromolla, A., Ingrosso, A., Volpi, V., Medaglia, C. M.,

Palatucci, M., Mariarosaria Pazzola, M., 2015.

Gamification in a Smart City Context. An Analysis and

a Proposal for Its Application in Co-design Processes,

Games and Learning Alliance, pp 73-82, Springer.

Uskov, A., Sekar, B., 2015. Smart Gamification and Smart

Serious Games, Fusion of Smart, Multimedia and

Computer Gaming Technologies, pp 7-36, Springer.

Goodchild, M.F., 2007. Citizens as sensors: the world of

volunteered geography, GeoJournal 69 (4): 211–221.

Fiedukowicz, A., Kołodziej, A., Kowalski, P., Olszewski,

R. 2013. Społeczeństwo geoinformacyjne i

przetwarzanie danych przestrzennych.” In: Rola bazy

danych obiektów topograficznych w tworzeniu

infrastruktury informacji przestrzennej w Polsce edited

by Robert Olszewski and Dariusz Gotlib, 300-306.

Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii, Warsaw.

Cecchini, A., 2015. Beyond smart cities: Antifragile

Planning for Antifragile City. Paper presented at the

15th International Conference on Computational

Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2015), Banff.

Clark, A. 2009. Serious Games: Complete Guide to

Simulations and Serious Games: How the Most

Valuable Content Will be Created in the Age Beyond

Gutenberg to Google. USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Cabena, P., Hadjinian, P., Dtadler, R., Verhees J., Zanasi

A., 1998. Discovering Data Mining: From Concept to

Implementation, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River;

Journal of Laws of 1995, No. 88, item 43, New York.

Fayyad U., Piatetsky-Shapiro G., Smyth P., 1996a. From

Data Mining to Knowledge Discovery in Databases, AI

magazine, vol. 17, no 3, Association for the

Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, s. 37-54.

Gąsiorowski J., Hajkowska M., Olszewski R., 2015. Spatio-

Temporal Modeling as a Tool of the Decision- Making

System Supporting the Policy of Effective Usage of EU

Funds in Poland, Springer International Publishing

Switzerland 2015 O. Gervasi et al. (Eds.): ICCSA 2015,

Part III, LNCS 9157, ss. 576-590.

Han J., Kamber M., 2000. Data Mining: Concepts and

Techniques, Morgan Kaufmann.

Hand D., Mannila H., Smyth P., 2001. Principles of data

mining, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Kantardzic M., 2003. Data mining: Concepts, Models,

Methods and Algorithms, John Wiley & Sons, NY.

Miller H.J., Han L., 2001. Geographic Data Mining and

Knowledge Discovery, Taylor & Francis, London.

Nisbet R., Elder J., Miner G., 2009. Statistical Analysis and

Data Mining Applications, Elsevier.

Piatetsky-Shapiro G., Frawley W.J., 1991. Knowledge

Discovery in Databases, AAAI/MIT Press.

Witten I.H., Frank E., 2005. Data Mining, Morgan

Kaufmann.

Fiedukowicz A., Gąsiorowski J., Olszewski R., 2015.

Wybrane metody eksploracyjnej analizy danych

przestrzennych (Spatial Data Mining), Wydział

Geodezji i Kartografii Politechniki Warszawskiej,

Warszawa, ISBN 978-83-916104-1-1.

Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City’s Development

181