Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional

Processes for Physiological Computing

Ferdinand Pittino

1

, Sandra Mai

2

, Anke Huckauf

1

and Olga Pollatos

2

1

General Psychology, Ulm University, Albert-Einstein-Allee 47, 89069 Ulm, Germany

2

Clinical and Health Psychology, Ulm University, Albert-Einstein-Allee 41, 89069 Ulm, Germany

Keywords: Hunger, Eye-tracking, Pupillometry, Visual Attention.

Abstract: Assessing users’ states becomes increasingly important also for technical systems. In the present study, we

assessed the influence of hunger on processing food versus household items by monitoring eye movements

in a picture categorization task. As indicator for sympathetic activation, pupil dilation was additionally

assessed in hungry and satiated participants. Food and household items were presented in the left and right

visual field and the task of the participants was to indicate whether the pictures in both visual fields

represented the same (household vs. food) or different categories (household and food). Although behavioural

data did not differ between hungry and satiated participants, more thorough investigations of gaze behaviour

showed that hungry participants were more impaired in processing household items than the satiated ones. In

addition, mean pupil dilation differed between hungry and satiated participants. Pupil size was shown to

correlate with hunger ratings suggesting that gaze-based measures can indeed serve as diagnostic tool for

sensing user states.

1 INTRODUCTION

Current technical systems are expected to react to the

intentions and dispositions of users. Hence,

knowledge about basic motivations of users and their

respective changes in behaviour are essential when

realizing affective computing systems. The technical

systems need to acquire their knowledge about the

user’s states by means of physiological measures.

Therefore, it is important to know how users react to

changes in bodily states as well as to respective

relevant stimuli. In the current study, we assessed

such physiological changes using the bodily state of

hunger and corresponding food versus household

images as relevant stimuli as an example.

Hunger is one of the most basic bodily

dispositions. One might assume that hunger affects

human attention and arousal. In addition, one might

suspect that it affects attending either towards all

stimuli or towards potentially eating-related stimuli

only. In the current study, this was investigated by

measuring eye movements and pupillary changes in

hungry versus satiated participants watching

comparable food and household images.

Hunger is known to influence many cognitive and

emotional processes in everyday life, which is

especially apparent in food-related behaviour:

Empirical data demonstrate that food deprivation

alters brain activation and subjective appeal to

pictures of high- and low-calorie food (Giel et al.,

2010; Goldstone et al., 2009; Piech et al., 2010) and

modulates activity in the food reward system (Siep et

al., 2009). It is also known that hunger is a potent

activator of the sympathetic nervous system

(Andersson et al., 1988; Chan et al., 2007; Pollatos et

al., 2012); various studies could demonstrate that

short-term food deprivation (up to 72 hours) leads to

an increased sympathetic and decreased

parasympathetic activation. For example, Chan et al.

(2007) demonstrated that short-term fasting increased

sympathetic activity as measured by heart rate

variability (HRV) and 24-hour urinary

catecholamines and decreased parasympathetic tone

(HRV) in humans.

In this context the model of neurovisceral

integration proposed by Thayer and Brosschot (2005)

is highly interesting. It states that autonomic

imbalance and reduced parasympathetic tone may be

the final common pathway linking negative affective

states to health problems, probably modulated by

interface regions like the prefrontal cortex, which is a

target region both for information from the central

152

Pittino, F., Mai, S., Huckauf, A. and Pollatos, O.

Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional Processes for Physiological Computing.

DOI: 10.5220/0006008301520160

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems (PhyCS 2016), pages 152-160

ISBN: 978-989-758-197-7

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

nervous system and attention, emotion and motivated

behaviour networks (Thayer and Brosschot, 2005). A

sympathetic activation and a parasympathetic

withdrawal has been demonstrated to be linked to

hypervigilance and inefficient allocation of

attentional and cognitive resources (Thayer and

Brosschot, 2005). A former study could show that

food deprivation provokes a parasympathetic

decrease and heightened sympathetic activity which

was associated with a hypervigilance to pain stimuli

both on a perceptual and emotional level (Pollatos et

al., 2012).

There are already reports indicating that eye

movements between hungry and satiated persons do

not differ (e.g. Nijs et al., 2010). However, there are

also observations that eye movements can be

diagnostic for eating behaviour (Werthmann et al.,

2011) in over-weight participants. Nevertheless,

whether hungry and satiated person process food

versus other images differently is still unclear. This

was to be examined in the present study.

Moreover, in video-based eye tracking, also pupil

dilation is given. As is evident, pupils of the eye are

activated by sympathetic nerves (e.g. Ehlers et al.,

2016; Partala and Surakka, 2003). Hence, pupillometry

can serve as an indicator of sympathetic activation. As

stated above, hunger is known to raise sympathetic

activation. Hence, one would expect observing larger

pupils in hungry relative to satiated participants.

Concerning food stimuli, numerous studies

demonstrated that nutrition state of the subjects

changed brain responses to food stimuli (Goldstone et

al., 2009; Siep et al., 2009; Stice et al., 2013). For

example, Goldstone and colleagues (2009) reported

that fasting increased activation to pictures of high-

calorie foods in various brain regions including the

ventral striatum, the amygdala, the anterior insula,

and medial and orbitofrontal cortex. Furthermore,

fasting enhanced the subjective appeal of high-calorie

foods, and the change in appeal bias towards high-

calorie foods was positively correlated with medial

and orbitofrontal cortex activation. The authors

concluded that fasting biased brain reward systems

towards high-calorie foods. Supporting these results,

also Stice and co-workers (2013) reported that the

duration of experimentally manipulated caloric

deprivation correlated positively with activation in

regions implicated in attention, reward, and

motivation in response to food images (including the

anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex).

They suggested that self-imposed caloric deprivation

increases responsivity of attention, reward, and

motivation regions to food, which may explain why

caloric deprivation weight loss diets typically do not

produce lasting weight loss (Stice et al., 2013).

These results are in accordance to Siep et al.

(2009) who reported that hunger interacts with the

energy content of foods, modulating activity in

several regions (e.g. cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal

cortex, insula). They showed that food deprivation

increased activity following the presentation of high

calorie foods and also followed that this fact may

explain why treatments of obesity energy restricting

diets often are unsuccessful. Extending these results,

Frank and co-workers (2010) reported that high-

caloric pictures compared to low-caloric pictures led

to increased activity in food processing and reward

related areas, like the orbitofrontal and the insular

cortex, but furthermore they found activation

differences in visual areas (occipital lobe), despite the

fact that the stimuli were matched for their physical

features. Frank et al. (2010) concluded that hunger

and the calorie content of food pictures also modulate

the activation of early visual areas. Having this in

mind, other measures than imaging techniques that

are rather slow in their response profile might help to

disentangle early effects of hunger on visual

processing of food stimuli.

Using other measures than imaging techniques,

Hepworth and co-workers (2010) manipulated mood

in healthy participants before using food stimuli in a

visual-probe task assessing attentional bias. They

showed that negative mood increased both attentional

bias for food cues and subjective appetite. Attentional

bias and subjective appetite were positively inter-

correlated, suggesting a common activation of the

food-reward system. Giel and colleagues (2011) used

eye tracking in a free viewing paradigm: They

reported that anorectic patients allocated overall less

attention to food. Interestingly, attentional

engagement for food pictures was most pronounced

in fasted healthy control subjects.

Till now, the question of whether different levels

of visual processing of food stimuli can be

distinguished using eye tracking when manipulating

hunger state in participants remains unanswered. As

hunger essentially influences everyday behaviour and

is an important variable in sensing the state of a

person in interaction to his/her environment, the aim

of the present study was twofold: First, we wanted to

clarify whether hunger leads to an attentional bias for

food pictures using different measures of eye tracking

(direction of the initial fixation, first fixation duration,

fixation count) allowing to distinguish perceptual

from evaluating processes. Second, we aimed to

elucidate whether pupillometry was a valid measure

for a sympathetic increase associated with hunger.

Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional Processes for Physiological Computing

153

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

In total 51 psychology students (40 females and 11

males, M

age

= 22.61, SD

age

= 3.92) of Ulm University

participated in this experiment for partial fulfilment

of course credit. All participants did not report a

history of eating disorder, had normal or corrected to

normal vision and provided informed consent based

on the guidelines of the German Research Foundation

(DFG). Due to technical difficulties (calibration and

data recording) the data of four participants were not

included in the analysis of the gaze data during the

food categorization task and six subjects were not

included in the analysis of the influence of hunger on

pupil size. Therefore, the sample for the food

categorization task (see Procedure) consisted of 47

participants (26 hungry, 38 females, M

age

= 22.77,

SD

age

= 4.05) and the final sample for the influence of

hunger on pupil size consisted of 45 participants (25

hungry, 37 females, M

age

= 22.93, SD

age

= 4.06).

2.2 Stimuli and Apparatus

As stimuli the pictures of food (e.g. bread) and

household items (e.g. handkerchief) used by Koch et

al. (2014) to study the attentional bias towards food

in overweight and obese children, were applied. The

advantage of this stimulus set consists in the similar

depiction of food and household items. Stimuli of

both categories were presented on a white plate.

The experiment was run on a Windows 7 PC and

was implemented using PsychoPy (Version 1.81.02;

Peirce, 2007). The stimuli were presented on a Dell

P2210 (resolution 1680 x 1050 px, refresh-rate 60 Hz)

which was stationed approximately 60 cm from the

participant. A remote eye-tracking system (RED250

with a sampling-rate of 120 Hz; SensoMotoric

Figure 1: Overview of the experimental setup.

Instruments, Teltow Germany) was attached to the

monitor and recorded gaze as well as pupillometric

data. The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 1.

2.3 Questionnaire Data

Besides the assessment of sociodemographic

variables (such as age and gender), the participants

were also asked whether they have suffered from any

kind of eating disorder in their lifetime. Height and

weight were assessed with a customary measuring

device and a customary digital scale. Furthermore, the

participants were asked to rate their subjective

feelings of hunger on the 8-item visual analogue scale

ranging from 0 to 10 of Flint, Raben, Blundell, and

Astrup (2000, e.g. “How hungry are you?”).

2.4 Procedure

In preparation for the study, the participants in the

food deprivation condition (n = 27) were asked not to

consume any food, alcohol or caffeine beginning at

8:00 pm on the day prior to their individual study

appointment, which was either until 8:00 am, 9:00 am

or 10:00 am. In contrast, the participants in the

satiated condition (n = 24) were asked not to change

their eating habits.

After arriving in the laboratory the weight and size

of the subjects were assessed and the participants

rated their subjective hunger feelings on the visual

analogue scale of Flint et al. (2000).

The experiment consisted of two parts. First, pupil

size was measured and afterwards, the experiment

aiming at exploring the processing of food and

household items in satiated and hungry participants

using eye-tracking was carried out.

The two parts of this experiment are now

described in more detail.

2.4.1 Pupillometric Measurement Phase

Participants’ pupil size was measured for five seconds

using the SMI RED250 eye-tracking system. To

avoid eye-movements, participants were instructed to

fixate on a black fixation cross, which was presented

centrally with a size of 0.6° on a homogenously white

screen (141.7 cd/m²). The luminance of the room was

kept constant at 75.3 lx (including the luminance of

the monitor).

2.4.2 Food Categorization Task

After the pupillary measurement phase, the food

categorization task was carried out. At its beginning

a 9 point calibration and 4 point validation was

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

154

performed.

In the food categorization task, a trial started with

the central presentation of a black fixation cross with

a size of 0.6° for 1 s. Subsequently, two pictures (each

9° x 6°) were peripherally presented in the left and

right visual field at an eccentricity of 9°. These

pictures either consisted of food (F) or household (H)

items (Koch et al., 2014; see Figure 1 for an

illustration). Therefore, there were four different

stimulus constellations: food items are presented on

both sides (FF), household items are presented on

both sides (HH), food items are presented on the left

and household items on the right side (FH) and

household items are presented on the left and food

items are presented on the right side (HF). The task

of the participants was to decide whether the objects

shown in both visual fields were representing the

same category (either both food or both household

items) or whether mixed categories were presented in

the left and right visual field. If the stimuli presented

on both sides represented the same category

participants were instructed to press the key ‘l’ on the

right hand-side of a standard QWERTZ-keyboard. If

the stimuli presented on both sides represented

different categories participants were instructed to

press the key ‘a’ on the left side of the keyboard.

The experimental block started with a short

training phase consisting of four trials, in which the

participants were familiarized with the task and the

stimuli’s appearances and categories. The test phase

consisted of 64 trials, 16 for each stimulus

combination (FF, HH, FH, HF). The order of the trials

was randomized. During this test phase, the gaze

position was continuously recorded.

2.5 Processing of the Oculomotor Data

2.5.1 Processing of Pupillometric Data

For processing of the pupillary signal, first, blinks and

saccades were removed from the data stream. Further,

values deviating more than 1.5 times the interquartile

range from the median were treated as artefacts and

were removed from the signal. The resulting missing

values were replaced using linear interpolation.

2.5.2 Processing of the Eye-movements Data

For processing the gaze data, we utilized the Be Gaze

(Version 3.5) software of SMI (SensoMotoric

Instruments, Teltow Germany).

As areas of interest (AOI), the left and right

stimuli were regarded. For these two AOIs, event

statistics were computed and exported. Afterwards,

the raw data were processed using Matlab R2015b

(Mathworks Inc.). Trials with very high or low

reaction times (median ± 1.5 interquartile range) were

dismissed. Additionally, for each variable, subject

and stimulus category an outlier analysis was

performed. Values deviating more than three times

the interquartile range of the median were not

considered in the adjunct analysis. Finally, all

dependent variables (initial fixation direction, first

fixation duration and fixation count) were extracted

separately for the different stimulus configuration

(FF, HH, FH, HF) and both visual fields (left, right).

In order to control for reliable computation of the

mean, only data of participants were considered,

which had at least eight remaining correct responses

per condition after the procedure, described above,

was carried out.

The data were descriptively and inferentially

analysed using SPSS (Version 21, IBM).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Hunger Ratings

In order to check whether the instruction to resign for

food during the last hours yielded in hungrier

participants, the reported feelings of hunger were

assessed. Since the eight items of the hunger scale of

Flint et al. (2000) showed high internal consistency (α

= .887), the items were averaged and combined into

one scale.

A t-test revealed that participants in the food-

deprivation condition indeed reported higher hunger

feelings than participants in the satiated condition

(t(30.47) = 4.92, p < .001, M

hungry

= 7.12 SD

hungry

=

1.30, M

satiated

= 4.41 SD

satiated

= 2.24). Therefore, we

conclude that the short-term food deprivation was

successful in manipulating the participants’ hunger

state.

3.2 Analysis of the Behavioral Data

One can assume that hunger speeds up motor

reactions and the processing of either stimuli

independent of their content (food and non-food) or

specific to the motivational relevant stimulus food.

To examine this question, we analyzed the

correctness and reaction times in the food

categorization task. The purpose of this analysis was

to investigate whether hungry and satiated

participants differed on a behavioral level in

processing the different stimuli (FF, HH, FH, HF).

The percentage of correct responses of the food

Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional Processes for Physiological Computing

155

categorization task was entered in a repeated

measures ANOVA with the within-subject factor

stimulus (FF: food pictures are presented in both

visual fields; HH: household items in both visual

fields; FH: food items in the left and household items

in the right visual field; HF: household items in the

left and food items in the right visual field) and the

between-subject-factor hunger (satiated vs. hungry).

This analysis revealed a main effect of stimulus

(F(1.39,62.74) = 25.55, p < .001, η² = .362).

Participants gave most correct responses, when food

items were presented in both visual fields (M =

95.3%, SE = 0.7%) and least correct response when

household items were presented in both visual fields

(M = 72.4%, SE = 3.6%). Mixed stimulus

combinations were rated equally good at 89.3% (SE

= 1.3%).

Reaction times for correct trials were entered in a

repeated measures ANOVA with the within-subject

factor stimulus (FF vs. HH vs. FH vs. HF) and the

between-subject-factor hunger (satiated vs. hungry)

for all 43 participants (24 hungry) who answered at

least eight trials per stimulus combination (FF, HH,

FH, HF) correctly. Again, the analysis revealed a

main effect for stimulus (F(1.74,71.35) = 36.98, p <

.001, η² = .474, see Figure 1). Participants reacted

especially fast when food was displayed in both

visual fields. They were slower when only household

items were presented and when a combination of food

and household items was shown. Furthermore, for

trials with mixed stimulus categories, reactions were

faster when food was displayed on the left side (FH)

compared to when it was presented on the right side

(HF). All other effects were not statistically

significant (F < 1).

Summarizing, there was no difference between

hungry and satiated participants, neither in percentage

of correct responses nor in reaction times. Both

dependent variables indicated that it was easiest to

react to stimuli, when food was presented in both

Figure 2: Reaction time in ms depending on the stimulus

configuration (FF, HH, HF, FH).

visual fields and that it was most difficult to react,

when household items were presented on both sides.

3.3 Analysis of the Eye Movements

Data

3.3.1 Initial Fixation Direction

One might assume that hunger produces a salience

signal for food items, thus boosting the amount of

initial fixations hitting the AOI containing food.

Hence, the direction of the initial fixation towards

either of the AOIs can be interpreted as the priority of

a certain visual field.

The present data clearly show that most of the first

fixations (M = 85.5%, SE = 0.02%) hit the left AOI.

The percentage of first fixations hitting the left AOI

was entered in a repeated-measures ANOVA with the

within-subject factor stimulus (FF vs. HH vs. HF vs.

FH) and the between-subject factor hunger (satiated

vs. hungry). This analysis revealed that the

percentage of initial fixations on the left AOI was

independent of the factors stimulus, hunger and the

interaction of both factors (all F < 1.5).

Summarizing, the data show that most of the

initial fixations hit the left AOI independently of the

stimulus which is displayed in the left or the subject’s

hunger state. This suggests that initial fixations

mainly indicate a certain processing strategy rather

than current user states.

3.3.2 First Fixation Duration

Considering the influence of hunger one might also

suppose that hunger results in a faster processing of

food stimuli. To examine this idea, the duration of the

first fixations on food versus household items was

analysed. The durations of the first fixation towards

the left AOI were entered in a repeated-measures

ANOVA with the within-subject factors stimulus-left

(household vs. food) and stimulus-right (household

vs. food) and the between-subject-factor hunger

(satiated vs. hungry).

The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of

stimulus-left (F(1,36) = 5.11, p = .03, η² = .124): That

is, independently of the hunger state, participants

fixated longer on the left AOI, when household items

were presented compared to food items (M

household

=

234.56 ms, SE

household

= 6.45 ms; M

food

= 222.27 ms,

SE

food

= 6.29 ms, see Table 1 for an overview of the

pattern of results). The other effects were not

significant (all F < 1.5).

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

156

Table 1: Mean duration of first fixation in ms on the left

AOI depending which stimulus category is presented in the

left (household vs. food) and in the right visual field

(household vs. food).

right visual field

household food

left

visual

field

household

M = 234.74

SE = 8.37

M = 234.38

SE = 6.93

food

M = 224.04

SE = 6.98

M = 220.49

SE = 7.07

A similar picture emerged for the right AOI. The

analysis revealed a main effect of stimulus-right

(F(1,36) = 7.96, p = .008, η² = .181), also reflecting the

fact that participants fixated longer on the right AOI

when household items were presented compared to

food items (M

household

= 308.78 ms, SE

household

= 9.81 ms;

M

food

= 288.22 ms, SE

food

= 8.17 ms). Besides this

effect of stimulus category, the analysis showed a main

effect of hunger (F(1,36) = 6.62, p = .014, η² = .155):

The duration of the first fixation on the right AOI was

longer for hungry participants compared to satiated

ones (M

hungry

= 319.75 ms, SE

hungry

= 11.05 ms; M

satiated

= 277.26 ms, SE

satiated

= 12.28 ms). The other effects

were not statistically significant (all F < 2.5).

Summarizing, the data showed that participants’

first fixation on an AOI was longer when household

items were presented at the respective side compared

to food items. Furthermore, on the right AOI the first

fixation was longer for hungry participants.

3.3.3 Fixation Count

Since hunger can be thought to increase the interest

into food stimuli and the ease of processing of either

all or only motivational relevant stimuli, also, the

number of fixations on either AOI was investigated.

We again conducted repeated-measures ANOVAs

with the within-subject factors stimulus-left

(household vs. food) and stimulus-right (household

vs. food) and the between-subject factor hunger

(satiated vs. hungry).

First, the results regarding the amount of fixations

on the left AOI are considered. The analysis revealed

that fixations on the left AOI were more frequent

when household items were presented compared to

when food was presented in the left visual field (main

effect for stimulus-left: F(1,31) = 18.62, p < .001, , η²

= .375). The interaction of stimulus-left and hunger

was significant (F(1,31) = 6.03, p = .020, η² = .163,

see Figure 2), indicating that hungry participants

fixated more often on household compared to food

items than satiated ones did. Besides, the interaction

of stimulus-left and stimulus-right reached

significance (F(1,31) = 12.03, p = .002, η² = .280):

When household items were presented in the right

visual field, the amount of fixations on the left AOI

was independent of stimulus category in the left

(M

household

= 2.17, SE

household

= .079; M

food

= 2.15, SE

food

= .10). However, for food items in the right visual

field the amount of fixations was higher when

household items (M

household

= 2.38, SE

household

= .091)

compared to food items were presented in the left

visual field (M

food

= 1.90, SE

food

= .078). The other

effects were not statistically relevant (all F < 2.5)

Second, the analysis for the amount of fixations on

the right AOI is reported. The repeated-measures

ANOVA revealed a main effect for the factor stimulus-

right (F(1,31) = 6.40, p = .017, η² = .171). As for the

left AOI, there were more fixations on the right AOI

when household-items were presented than when food

items were presented (M

household

= 1.85, SE

household

=

0.05; M

food

= 1.73, SE

food

= 0.06). Furthermore, there

were more fixations on the right AOI, when household

items relative to food items were presented in the left

visual field (stimulus-left: (F(1,31) = 12.60, p = .001,

η² = .289; M

household

= 1.87, SE

household

= 0.06; M

food

=

1.70, SE

food

= 0.05). The other effects were not

statistically significant (all F < 1.5).

Summarizing the important results concerning our

question at issue, the amount of fixations was higher

on household items than on food items. For the left

AOI the amount of fixations on household items was

even higher for hungry compared to satiated

participants.

Figure 3: Amount of fixations on the left AOI depending on

the stimulus presented in the left visual field and hunger.

Error bars reflect the standard error of the mean.

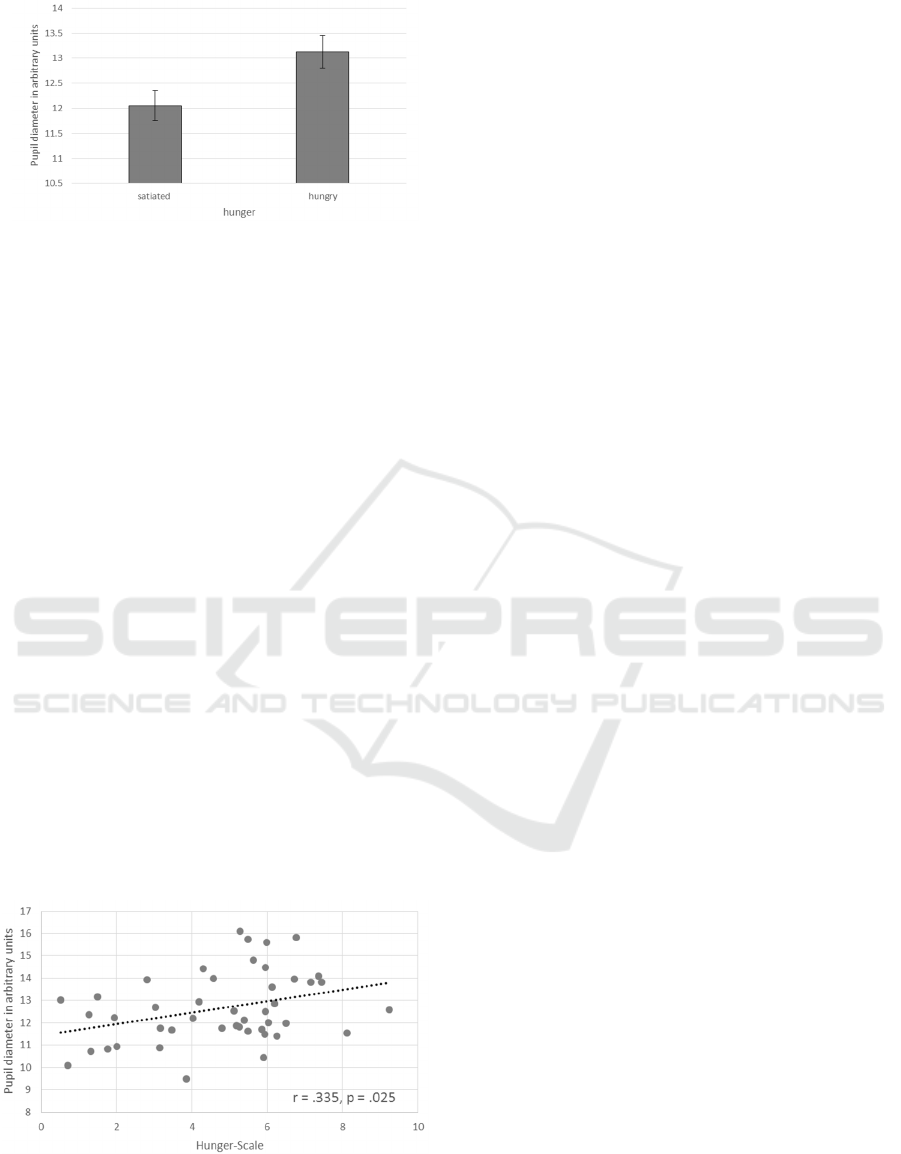

3.4 Analysis of the Pupillometric Data

Due to the algorithm outlined in the method section

in average 9.7% (SD = 8.2%) of data points were

Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional Processes for Physiological Computing

157

Figure 4: Mean pupil diameter in dependence of hunger.

Error bars reflect the standard error of the mean.

treated as artefacts and were replaced using linear

interpolation. The pupillary data were then averaged

over the 5 s recording time. An independent samples

t-test revealed larger pupils for hungry compared to

satiated participants (t(43) = 2.40, p = .021, ΔM =

1.08, SE = 0.45, see Figure 3). Importantly, pupil size

and the individual ratings on the hunger scale

correlated positively and highly (r = .375, p = .011;

see Figure 4). That is, the higher the ratings on the

hunger scale, meaning that participants felt hungrier,

the larger the pupils.

Therefore, the data do not only indicate that

hungry participants showed larger pupil sizes than

satiated ones, but that their individual feelings of

hunger are correlated with this physiological

measure.

4 DISCUSSION

In the present study we investigated whether a bodily

drive like hunger leads to an attentional bias towards

relevant (i.e., food) pictures. This was examined using

measures of eye movements allowing an examination

of early perceptual processes. Second, we aimed to

Figure 5: Correlation between pupil size and the ratings on

the hunger-scale of Flint et al. (2000).

elucidate whether pupillometry is a valid measure for a

sympathetic increase associated with hunger.

First of all, we derived at investigating differences

between more and less hungry participants, as

instructions and subjective reports confirmed. In

addition, referring to overt performances in a

classification task using food and household items as

stimuli, there was no difference between hungry and

satiated participants observable. Also the direction of

the first fixation was unaffected by hunger as well as

by the stimulus category.

Nevertheless, effects of hunger could be observed

in more implicit gaze signals: The first fixation

duration was longer on the right AOI for hungry

compared to satiated ones. While all participants had

fixated more often on household items, this effect was

more pronounced for hungry participants. Hence, we

observed an interaction of hunger and stimulus

category. The results are now discussed in more detail.

Using the direction of the initial fixation we aimed

at examining an early attentional bias towards food

items for hungry participants and investigated the

priority of a visual field. We found that most of the

initial fixations hit the left AOI independent of the

displayed stimulus configuration and participants’

state of hunger. Thus, in completing the task

participants followed normal reading direction and

started at the left and later changed to the right AOI.

This effect suggests that in the current set-up, the

initial fixation direction indicates more a routine

behaviour being less influenced by the bodily

disposition of hunger and the stimulus category. Our

results are in contrast to the study of Giel et al. (2011)

who found that hungry participants initially fixated

more often on food items. However, there are some

important differences in the study design which might

account for the different results. Giel et al. (2011)

employed a free viewing paradigm without a specific

task whereas we instructed the participants to classify

whether the same category or different categories

were presented in the visual fields. Furthermore, we

instructed our participants to react as fast and as

accurately as possible. This could have resulted in a

more rigid deployment of practiced search

techniques. Additionally, the distance between the

two AOI was larger in our study. This difference

might be important, as a greater distance between the

centered fixation cross and the AOI might have

impaired peripheral preprocessing of the stimuli.

Additionally, peripheral preprocessing may have

been impaired by the similar depiction of food and

non-food items on a white plate: This similar

depiction and the fact that both stimuli were presented

on a white plate, which may be a cue for food items,

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

158

could have diminished the effects of peripheral

perception on the direction of the initial fixation.

More research in this field is needed to clarify the

boundaries of peripheral preprocessing in hungry

participants, when food and non-food items are

presented while also controlling for stimulus

characteristics of these two categories.

The results for first fixation durations showed that

first fixations were longer when household items were

shown compared to food items. This also becomes

clear when considering that household items were

presented on plates. It is obviously odd to see

household items (like keys) presented on a white plate.

We found longer first fixation durations on the right

AOI for hungry participants. When assuming that

fixations towards the left in the current set-up reflect

rather strategic processes, fixations towards the right

might be regarded as more prone to user states.

A similar picture emerged for the amount of

fixations on the AOIs: Overall, there were more

fixations towards household items than towards food

items supporting the assumption that household items

presented on a plate are unfamiliar and therefore more

difficult to process. But again, this effect was more

pronounced for hungry subjects. This indicates that

processing of non-food stimuli – the less relevant or

more distracting category when being hungry - is

impaired in hungry participants.

Our results are in accordance to former studies

showing that hunger and the calorie content of food

pictures also modulates the activation of early visual

areas (Frank et al., 2010). The present study

substantially extends these findings by showing that

hunger might also affect effectiveness of visual

search as indicated by longer fixation duration in

hungry participants when food is presented in the

paradigm. As we did not use a separate task with non-

food stimuli only, potential expectation effects

concerning food might have influenced the HH-

categorization too. In addition to that, presenting

household objects like keys on a plate might have

increased the association with food for these objects

as only food is usually presented or served on plates.

Therefore, future research should consider using a

more naturalistic display of household items.

Previous studies already confirmed the increase in

sympathetic activation and decrease in

parasympathetic activation of hunger (Chan et al.,

2007). Given that pupil size is influenced by

sympathetic activation (e.g. emotional arousal, Ehlers

et al., 2016; Partala and Surakka, 2003), it was

hypothesized that pupil dilation can be linked to

hunger. The results of the present study indeed

demonstrate the first time that the pupils of hungry

participants are more dilated than the pupils of

satiated ones. Moreover, the data show that pupil size

and subjective hunger are positively correlated

suggesting that this measure can also serve for

diagnostic purposes. For user sensing, this means that

pupil dilations have to be carefully interpreted with

regard to potentially activating sources. That is,

whether or not this method allows to discriminate

between different sources of bodily arousal such as

mental stress has to be further elucidated in future

research. Besides, taking additional sources of bodily

arousal into account, further studies should also

examine whether user characteristics such as weight,

height or psychological disorders such as eating

disorders influence the results of hunger on

sympathetic activation and attentional processing.

Hence, our study indicates that pupillometry is a

feasible way to quantify bodily arousal as associated

with hunger feelings. This method is therefore an

innovative way to assess physiological processes in

the context of bodily states.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank Andreas Stegmaier for his help in

data collection.

REFERENCES

Andersson, B., Wallin, G., Hedner, T., Ahlberg, A. C., &

Andersson, O. K. (1988). Acute effects of short-term

fasting on blood pressure, circulating noradrenaline and

efferent sympathetic nerve activity. Acta Medica

Scandinavica, 223(6), 485–490.

Chan, J. L., Mietus, J. E., Raciti, P. M., Goldberger, A. L.,

& Mantzoros, C. S. (2007). Short-term fasting-induced

autonomic activation and changes in catecholamine

levels are not mediated by changes in leptin levels in

healthy humans. Clinical Endocrinology, 66(1), 49–57.

Ehlers, J., Strauch, C., Georgi, J., & Huckauf, A. (2016).

Pupil Size Changes as an Active Information Channel

for Biofeedback Applications. Applied

Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Flint, A., Raben, A., Blundell, J. E., & Astrup, A. (2000).

Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue

scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test

meal studies. International Journal of Obesity, 24(1),

38–48.

Frank, S., Laharnar, N., Kullmann, S., Veit, R., Canova, C.,

Hegner, Y. L., et al. (2010). Processing of food pictures:

Influence of hunger, gender and calorie content. Brain

Research, 1350, 159–166.

Giel, K. E., Friederich, H.-C., Teufel, M., Hautzinger, M.,

Enck, P., & Zipfel, S. (2011). Attentional processing of

Effects of Hunger on Sympathetic Activation and Attentional Processes for Physiological Computing

159

food pictures in individuals with anorexia nervosa--an

eye-tracking study. Biological Psychiatry, 69(7), 661–

667.

Giel, K. E., Teufel, M., Friederich, H.-C., Hautzinger, M.,

Enck, P., & Zipfel, S. (2010). Processing of pictorial

food stimuli in patients with eating disorders-A

systematic review. International Journal of Eating

Disorders, 105–117.

Goldstone, A. P., Prechtl de Hernandez, Christina G.,

Beaver, J. D., Muhammed, K., Croese, C., Bell, G., et

al. (2009). Fasting biases brain reward systems towards

high-calorie foods. European Journal of Neuroscience,

30(8), 1625–1635.

Hepworth, R., Mogg, K., Brignell, C., & Bradley, B. P.

(2010). Negative mood increases selective attention to

food cues and subjective appetite. Appetite, 54(1), 134–

142.

Koch, A., Matthias, E., & Pollatos, O. (2014). Increased

Attentional Bias towards Food Pictures in overweight

and Obese Children. Journal of Child and Adolescent

Behavior, 2(2), 1000130.

Nijs, I. M., Muris, P., Euser, A. S., & Franken, I. H. (2010).

Differences in attention to food and food intake

between overweight/obese and normal-weight females

under conditions of hunger and satiety. Appetite, 54(2),

243–254.

Partala, T., & Surakka, V. (2003). Pupil size variation as an

indication of affective processing. International Journal

of Human-Computer Studies, 59(1-2), 185–198.

Peirce, J. W. (2007). PsychoPy - Psychophysics software in

Python. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 162(1-2), 8–

13.

Piech, R. M., Pastorino, M. T., & Zald, D. H. (2010). All I

saw was the cake. Hunger effects on attentional capture

by visual food cues. Appetite, 54(3), 579–582.

Pollatos, O., Herbert, B. M., Füstös, J., Weimer, K., Enck,

P., & Zipfel, S. (2012). Food deprivation sensitizes pain

perception. Journal of Psychophysiology, 26(1), 1–9.

Siep, N., Roefs, A., Roebroeck, A., Havermans, R., Bonte,

M. L., & Jansen, A. (2009). Hunger is the best spice: an

fMRI study of the effects of attention, hunger and

calorie content on food reward processing in the

amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. Behavioural Brain

Research, 198(1), 149–158.

Stice, E., Burger, K., & Yokum, S. (2013). Caloric

deprivation increases responsivity of attention and

reward brain regions to intake, anticipated intake, and

images of palatable foods. NeuroImage

, 67, 322–330.

Thayer, J. F., & Brosschot, J. F. (2005). Psychosomatics

and psychopathology: looking up and down from the

brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), 1050–1058.

Werthmann, J., Roefs, A., Nederkoorn, C., Mogg, K.,

Bradley, B. P., & Jansen, A. (2011). Can(not) take my

eyes off it: Attention bias for food in overweight

participants. Health Psychology, 30(5), 561–569.

PhyCS 2016 - 3rd International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems

160