Analyzing a Knowledge Country

How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?

Maria Obeso

1

and Maria Jesus Luengo-Valderrey

2

1

Department of Business Administration, University of Cantabria, Avenida de los Castros, Santander, Spain

2

Department of Management Evaluation and Business Innovation, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain

Keywords: Knowledge Country, Sweden, Innovation, Knowledge Management, Innovation Strategy.

Abstract: In a scenario where knowledge is considered an essential tool for firms and organizations, the paper

presented an analysis about how Sweden, considered as a knowledge country, manages its innovation

process. First, the paper presents the measures that Sweden government are doing, exposing the essential

points in its innovation strategy. Then, the behaviour of Swedish enterprises related to innovation is

analysed. Using an ANOVA technique, the paper shows that there are not differences between Swedish

regions managing innovation, but there are differences between industries. After that, a comparison between

industries in order to analyse which are the differences has been realized. Results show that machinery and

retail industries are the most innovative, and fabricated metal industry is considered the least innovative.

Although there are differences between industries, results show that in general Swedish enterprises are

innovative because only a 9 per cent of enterprises have not realized something related to innovation

process.

1 INTRODUCTION

At the present time, knowledge is considered an

essential tool for organizations to achieve a

competitive advantage. (Nonaka and Takeuchi,

1995; Von Krogh, 2012), to such an extent that it

has been claimed that we live in a Knowledge

Society (Sakaiya, 1991). But not all organizations

and enterprises manage their knowledge in the same

way leading to differing business outcomes.

This paper examines how a country like Sweden,

considered as a knowledge country (Sarabia et al.,

2012), manages its innovation activity. This includes

both the actions of the Government and also, how

enterprises manage this activity. This case is of

particular interest because according to Sarabia et al.

(2012) Sweden represents an example for other

countries to follow. Therefore, the main question is:

how does Sweden (both the government and at

business level) manage innovation activity?

In order to answer this question, the paper is

structured as follows: First, a theoretical framework

is presented highlighting innovation activity. Then,

the Swedish case is presented, analyzing in the first

place the government´s own program and then the

behaviour of individual Swedish companies; in order

to analyze the last point, an empirical analysis is

presented using ANOVA to determine if there are

differences between industries and/or regions

(region 1: Stockholm-Solna, region 2: Boras,

Goteborg, Jonkoping, Trollhattan-Vanersborg,

region 3: Malmo-Lund and region 4: Linkoping,

Orebro, Karlstad, Vasteras). Finally, the conclusions

of the study are presented along with the principal

findings, implications, limitations and future

research possibilities.

2 INNOVATION

Innovation is defined as “the implementation of a

new or significantly improved product (goods or

services), or process, a new marketing method, or a

new organisational method in business practices,

workplace organisation or external relations” (Oslo

Manual, 2005: 46). That is to say, innovation is

related to the idea of change or something new

(Formichella, 2005) and it is considered a

knowledge process with the aim of create new

knowledge and developing solutions (Herkema,

2003).

Innovation is essential for both survival and

124

Obeso, M. and Luengo-Valderrey, M.

Analyzing a Knowledge Country - How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?.

DOI: 10.5220/0006036801240131

In Proceedings of the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2016) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 124-131

ISBN: 978-989-758-203-5

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

competitiveness, whether for individual enterprises

or for countries (OECD, 2010). This process

contributes towards economic growth (Schumpeter,

1934) and plays an essential role in regional

development (Schiuma and Lerro, 2008), with

governments playing a role in stimulating innovative

activity in individual enterprises (Gondora et al.,

2010). Therefore research on this topic is of great

importance for present-day society because it helps

to create an environment of sustainability (Luengo

and Obeso, 2012).

The innovation process is also linked to research

and development activity. Regarding the previous

paragraph, within innovative enterprises there are

R&D workers, and these workers are important for

establishing knowledge networks and the business

outcomes of the firm (Huber, 2013). Following

Humerlinna-Laukkanen et al., (2012), R&D is

linked to innovation performance and innovation

networks and, R&D is itself influenced by capability

and network stability. In other words there is a direct

relationship between innovation and the

performance of the firm in question (Liao et al.,

2010).

Innovation management is defined as “a process

of change, incremental or substantial, in products,

processes, organization and/or marketing that

includes all the enterprise and involves interaction

with environment” (Camio et al., 2014: 31).

Additionally, innovation management includes the

relationships within the organization that influences

the innovation process, whether between employees

between the organization and the environment

(Arango Londono, 2012).

3 THE CASE OF SWEDEN

3.1 Government´s Programme

The importance of innovation for the Swedish

government is demonstrated by the fact that they

have devised a plan for innovation, proposing an

innovation strategy for the entire country. This plan

has been made universally available in order to

promote innovation. The plan is entitled The

Swedish innovation strategy and its stated purpose is

“to contribute to a climate with the best possible

conditions for innovation in Sweden with year 2020

in sight” (Government Offices of Sweden, 2015: 5).

The main information contained in this document is

summarized in this section.

In more detail, the Swedish government has three

aims: (1) that Sweden contributes to innovative

solutions to global challenges, (2) that Sweden

increases its competitiveness in a global world

where knowledge is an essential activity, and (3) that

public services in Sweden achieve greater efficiency.

In order to achieve these aims, the strategy has

three pillars: (1) providing the best possible

conditions for innovation, (2) the people, businesses

and organisations that work systematically with

innovation and (3) implementation of the strategy

based on a holistic view. Subsections 3.1.1 to 3.1.3

discuss there in greater detail.

3.1.1 The Best Possible Conditions for

Innovation

This pillar is based on the personal skills and

infrastructure necessary to promote knowledge and

innovation. In this way, Swedish citizens must have

the necessary knowledge and skills needed in order

to contribute to the innovation process and, the

willingness to do so. The climate should also

promote innovation. In order to achieve this goal,

Swedish government has developed various

proposals.

With respect to individuals and their skills and

levels of willingness, Sweden should continue

investment in its educational system, which is seen

as essential in imparting knowledge and promoting

willingness, creativity, innovation and

entrepreneurship without gender or racial

stereotypes. These developments should be

implemented in close partnership with the business

world to adapt the learning process to the

requirements of business.

Inside the educational system, higher education

plays a fundamental role because universities are the

cradle of knowledge. The Swedish government

wants the quality of education and research in

Sweden to reach the highest international quality

standards and measures have been implemented to

achieve this goal.

On the one hand, the government wishes to

promote excellence in university level research by

developing an environment where both Swedish and

foreign researchers can carry out innovative work.

To achieve this, a law has been passed supporting

knowledge-based research conducted by students

and researchers. In addition, incentives to encourage

cooperation between universities and wider society

are already in place in Swedish universities.

On the other hand, research institutes are also

important in innovation activity, therefore

collaboration between these institutes, universities,

industries and public administration should be

Analyzing a Knowledge Country - How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?

125

promoted. The activities of the Industrial Research

Institute, created with the aim of supporting small

and medium businesses in their innovation process,

is of particular note in this area.

Knowledge sharing is related to mobility. In this

sense, the Swedish proposal aims to facilitate

mobility between business, organizations, industries,

regions and even countries to share different

knowledge. In addition, a diverse and innovative

workplace will be attractive to foreign workers, the

European Union being useful in this respect because

it opens Sweden up to a wider labor market.

Finally the government should develop an ideal

framework where positive attitudes to

entrepreneurship and innovation in society become

reality. In this framework inventions and intellectual

property are protected and taxes and lend capital is

equity.

3.1.2 People, Businesses and Organisations

that Work Systematically with

Innovation

Swedish organizations must have the knowledge

necessary to achieve a world-class capacity for

innovation. Therefore Sweden needs to develop

internationally competitive conditions to promote

cooperation and competition, facilitating the growth

of small and medium-sized businesses that are

primarily related to the process of innovation.

Linked to this goal, cooperation is considered an

essential condition for sharing knowledge and

innovation. This includes not only Swedish agencies

like universities, public administration, institutes and

small, medium and large enterprises, but also foreign

businesses. In this sense, internationalization is

presented as a convenient tool for enterprises,

because learning related to other cultures and

languages opens a door for the future.

The Swedish government will promote

innovative businesses and create collaboration

between agencies and the new information and

communication technologies (ICTs), a key resource

for increasing national and international potential in

small and medium firms.

The challenge for the government is to

communicate the idea that knowledge and

entrepreneurship are the key to producing and

developing new goods, services, systems and

business models and, therefore necessary for

raising competitiveness.

In addition, public services play an essential role

because they should be innovative, collaborative and

efficient, with a high level of quality and

availability. In this way, public services will

promote opportunities for innovation by developing

initiatives that support this process. Public

administration is essential for collaborate with

agencies and increasing innovation and

competitiveness.

3.1.3 Implementation of the Strategy based

on a Holistic View

Planning is very important, but implementation is

also fundamental. The starting point is the existing

interrelationship between Swedish agencies that

have an influence on the strategy and with foreign

agencies, or in other words: Swedish strategy should

take a holistic view where the result is the sum of the

parts.

The Swedish Government is faced with the

challenge of creating and promoting an innovative

environment while paying attention to the different

areas and social actors. Success therefore is

dependent on, an implementation strategy that

includes a bilateral relationship between government

and other players with the government keeping up to

date about the evolution of this situation

The aim is that Sweden will be a source of global

inspiration for other countries because of its strong

innovative climate.

3.2 What Swedish Companies do?

3.2.1 Data Collection and Methodology

Data has been collected in Sweden by the World

Bank, covering the period between January 2014

and November 2014. A total of 600 businesses were

successfully interviewed about their activities during

the previous year (2013). In the information

provided on data collection, it is stated that, the

sample for Sweden was selected using stratified

random sampling in order to make sure that the

final, complete sample included establishments from

all different sectors and that unbiased estimates for

different subdivisions of the whole population were

obtained. The data included questionnaire-based

responses to questions in the following areas:

general information, infrastructure and services,

sales and supplies, degree of competition,

innovation, capacity, land and permits, crime,

finance, business-government relations, labor,

business environment and performance.

The database was obtained from the Microdata

Library, a service established by Enterprise Surveys

( World Bank) to provide information about people

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

126

living in mainly developing countries (World Bank,

2016), but information has also been collected on

certain developed countries such as Sweden.

The companies surveyed belonged to the

following industries: fabricated metals, machinery

and equipment, other manufacturing, automotive

services, other services and retail (six categories).

The authors of the present study had access to the

database in April 2016, when the last available data

for Sweden dated from 2013.

For the analysis, an Analysis of Variance

(ANOVA) has been used. ANOVA is a statistical

method used with the aim of comparing different

groups with respect to one or more quantitative

variables. In this way the method is used to analyze

whether or not differences exist between groups

(Hair et al., 1995).

3.2.2 Analysis about Swedish Enterprises

The starting point was to analyze the differences

between Swedish companies managing innovation in

different industries in Sweden The following

variables related to innovation activity were

selected: whether the company had recently

introduced new or significantly improved products

or services (h1), the introduction or otherwise of

any new or significantly improved methods of

manufacturing products or offering services (h3), the

introduction of any new or significantly improved

logistics, delivery, or distribution methods for

inputs, products or services (h4a), the introduction of

any new or significantly improved systems or

activities to support their main operations, such as

maintenance systems or operations for purchasing,

accounting or computing (h4b), the introduction of

any new or significantly improved organizational

structures or management practices (h5), the

introduction of new or significantly improved

marketing methods (h6), and money spent on formal

research and development (R&D) activities, either

in-house or contracted out to other companies (h7).

In all cases, using Levene´s test, the null hypothesis

was rejected if a significance of less than 0.05 was

obtained, indicating that variances between variables

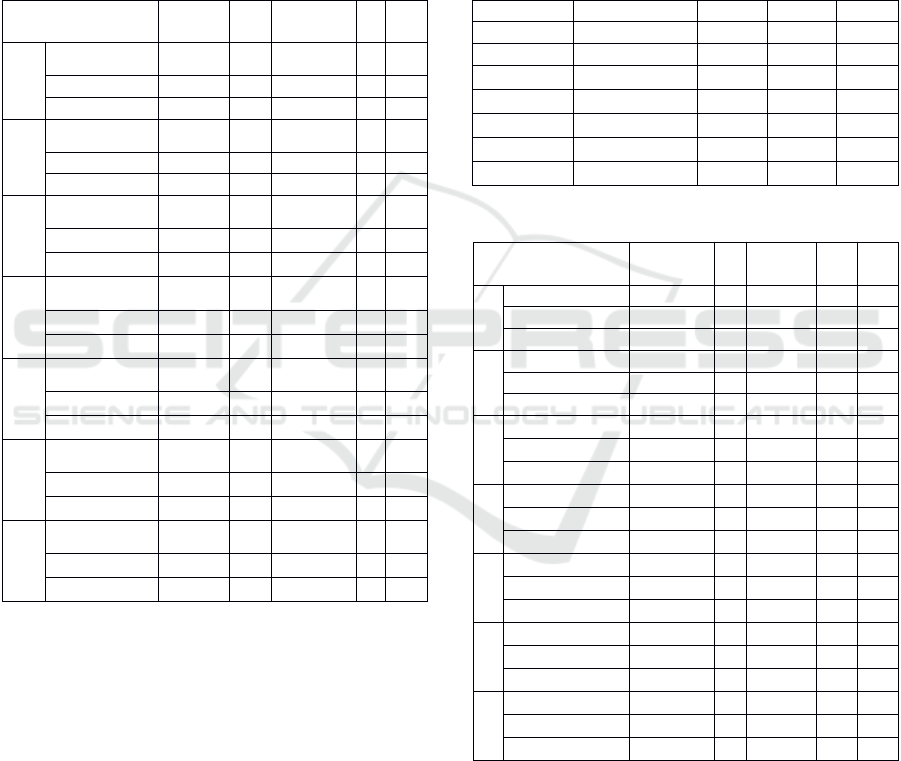

are different (see Table 1). Potential differences in

innovative activity between the 6 industrial sectors

were also tested. .

Then a post-hoc comparison was carried out

using T2 from Tamhane´s test (see Table 2).

Significant differences of less than 0,05 were found

between industrial sectors for all variables except for

h3, h4a, h4b and h5, thus confirming significant

differences in variance between industries linked to

the following variables: h1, h6 and h7.

Table 1: Levene´s test linked to industries in Sweden.

Variable

Levene´s test d.f1 d.f2 Sig.

h1

13,156 5 559 0,000

h3

3,808 5 559 0,002

h4a

3,489 5 559 0,004

h4b

5,499 5 559 0,000

h5

3,370

5

559 0,005

h6

4,532 5 559 0,000

h7

45,376 5 559 0,000

Moreover, the same Analysis of Variance

technique (ANOVA) was repeated in order to

discover if there were possible differences in how

companies managed innovation between the four

regions in Sweden From this starting point, the

same variables were selected (h1, h3, h4a, h4b, h5,

h6 and h7) as in the previous analysis. However, in

this case applying Levene´s test to the results gave a

value of more than 0.05 in all cases except for h4a

and h4b, and therefore the null hypothesis could not

be rejected in h1, h3, h5, h6 and h7. That is to say,

there were no differences between variances in these

variables.

To confirm the obtained results post-hoc

comparison was performed using T2 from

Tamhane´s test (see Table). Results show that the

significance was greater than 0,05 in all cases, and

that, therefore, geographical location (as defined by

the region variable) did not influence the results.

It was additionally considered useful to examine

exactly what innovation activities occurred within

each industry Subsections 3.2.3 to 3.2.7 deal with

the different kinds of industry. Section 3.2.8 presents

a comparison between them.

3.2.3 Fabricated Metals (Ind1)

There were 117 businesses (n) included in the

fabricated metal industry (ind1) with an average age

of around 39 years (b5) and their market was

predominantly national (64,15 per cent of sales

were national) (d3a). The majority of businesses

were small to medium size (almost 75 per cent) (see

Figure 1) and the average growth, measured using

differences in the number of employees between the

year of the survey and three years previously was

around 2,86 per cent (L2) (see Table 5).

This industry was characterized by low levels of

innovative behaviour. Only 68,4 per cent of

businesses, the lowest figure for any industry, had

introduced new products or services in the previous

three years. And only 53 per cent of firms had

Analyzing a Knowledge Country - How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?

127

introduced new products or services to the market

(h2), again the lowest figure. Similarly, only 36 per

cent of firms had introduced new logistics in the

previous three years, with around 56 per cent

introducing new maintenance systems and around 36

per cent introducing new marketing methods. With

respect to investment in R&D, the percentage of

businesses making an investment was also lower, at

only 35,9 per cent and investment in formal training

for employees was also the lowest (62.4 per cent).

Table 2: ANOVA results by industries in Sweden.

Variable

Sum of

squares

df

Mean

square

FSig.

h1

Between group

s

2,304 5 0,461

2,55

2

0,027

Within group

s

100,959 559 0,181

Tot

a

103,264 564

h3

Between group

s

1,138 5 0,228

0,95

2

0,447

Within group

s

133,633 559 0,239

Tot

a

134,772 564

h4a

Between group

s

1,598

5

0,320

1,34

8

0,242

Within group

s

132,515

559

0,237

Tot

a

134,113

564

h4

b

Between group

s

2,178

5

0,436

1,87

3

0,097

Within group

s

130,024

559

0,233

Tot

a

132,202

564

h5

Between group

s

1,174

5

0,235

1,05

7

0,384

Within group

s

124,270

559

0,222

Tot

a

125,444

564

h6

Between group

s

8,716

5

1,743

7,35

3

0,000

Within group

s

132,513

559

0,237

Tot

a

141,228

564

h7

Between group

s

13,734

5

2,747

12,8

5

0,000

Within group

s

119,452

559

0,214

Tot

a

133,186

564

3.2.4 Machinery (Ind2)

There were 112 businesses included in the

machinery industry (ind2) with an average age of

around 45 years with sales mainly proceeding from

direct exports (d3c) (44,19 per cent) follow very

closely by national sales (43,79 per cent). The

majority of businesses were classified as medium or

large (see Figure 1) and the average growth was 5,23

per cent (see Table 5).

The machinery industry was characterized by its

proactive approach to innovative activities. More

than 87 per cent of businesses had introduced new

products or services in the previous three years and,

of these, almost 78 per cent were also new to the

market. In addition, 67 per cent of businesses had

introduced new process in the previous three years,

with 36,6 per cent introducing new distribution

methods, more than 62 per cent introducing new

maintenance systems and 72,3 per cent of

enterprises introducing new structures (the highest

figure of any industry). In addition, investment in

R&D was also the highest (almost 60 per cent of

businesses having invested in research and

development) (see Table 5).

Table 3: Levene´s test by regions in Sweden.

Variable

Levene´s test d.f1 d.f2 Sig.

h1

1,736 3 561 0,159

h3

1,502 3 561 0,213

h4a

5,902

3

561 0,001

h4b

3,116

3

561 0,026

h5

1,520

3

561 0,208

h6

0,023

3

561 0,995

h7

1,627

3

561 0,182

Table 4: ANOVA test linked to regions in Sweden.

Variable

Sum of

squares

d

f

Mean

square

F

Sig.

h1

Between groups 0,226 3 0,075

0,411 0,745

Within groups 103,038 561 0,184

Total 103,264 564

h3

Between groups 0,415 3 0,138

0,578 0,630

Within groups 134,357 561 0,239

Total 134,772 564

h4a

Between groups 1,285

3

0,428

1,810 0,144

Within groups 132,828

561

0,237

Total 134,113

564

h4b

Between groups 0,842

3

0,281

1,198 0,310

Within groups 131,360

561

0,234

Total 132,202

564

h5

Between groups 0,224

3

0,075

0,334 0,801

Within groups 125,221

561

0,223

Total 125,444

564

h6

Between groups 0,217

3

0,072

0,287 0,835

Within groups 141,012

561

0,251

Total 141,228

564

h7

Between groups 0,346

3

0,115

0,487 0,692

Within groups 132,840

561

0,237

Total 133,186

564

3.2.5 Other Manufacturing (Ind3)

There were 115 businesses included in the other

manufacturing industry category (ind3) with an

average age of around 52 years (the highest average)

and their sales mainly proceeded from national

activity (almost 66 per cent). The majority of were

classified as medium or large (see Figure 1) and the

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

128

average growth was the lowest at 2,23per cent (see

Table 5). It seems that this industry is largely

composed of mature enterprises.

Table 5: Comparison between industries.

Ind1 Ind2 Ind3 Ind4 Ind5 Ind6

n

117 112 115 73 83 65

b5

39,48 45,04 51,5 35,21 26,46 18,57

b7

21,68 20,7 22,7 26,71 24,08 24,25

d3a

64,15 43,79 65,9 95,89 90,69 96,55

d3b

17,35 11,13 10,23 1,01 1,58 0,08

d3c

18,5 44,19 23,86 3,1 7,73 3,37

L2

2,86 5,23 2,23 9,38 5,25 6,13

L9a

10,9 10,98 11,14 11,5 12,2 -

h1

68,4 87,5 75,7 72,6 73,5 76,9

h3

65 67 55,7 58,9 56,6 58,5

h4a

36,8 36,6 32,2 39,7 44,6 49,2

h4b

56,4 62,5 68,7 68,5 53 69,2

h5

64,1 72,3 68,7 67,1 57,8 69,2

h6

36,8 47,3 37,4 68,5 55,4 67,7

h7

35,9 59,8 48,7 11 32,5 23,1

L10

62,4 66,1 73 79,5 69,9 80

h2

53,8 77,6 71,3 77,4 78,7 64

Figures for innovative activity were as follows:

75,7 per cent of enterprises had introduced new

products or services, and of these, more than 71 per

cent were also new to the market. Figures linked to

new processes and logistics were the lowest (at 55,7

and 32,2 per cent respectively). Around 68 per cent

of businesses had introduced new maintenance

systems and structures, and the figures concerning

the introduction of new logistics and new marketing

methods were 32,2 and 37,4 respectively. Finally

investment in R&D was in the middle (around 49

per cent) and investment in formal training was high

(73 per cent) (see Table 5).

3.2.6 Automotive Services (Ind4)

There were 73 businesses included in the

Automotive services industry (ind4) with an average

age of around 35 years and with sales mainly

proceeding from the national market (more than 95

per cent). The average score for manager

experience was the highest, at almost 27 years of

experience. The majority of enterprises were

classified as small or medium (see Figure 1) and

average growth was the highest (9,38 per cent) (see

Table 5). This industry therefore experienced the

fastest growth over the previous three years, as

measured by rise in total number of employees .

The automotive services industry stood out in

terms of marketing innovations: almost 69 per cent

of businesses having introduced a new marketing

method in the previous three years, the highest

figure. In addition, the investment in formal training

was also high (around 80 per cent). However the

investment in R&D activity was the lowest, with

only 11 per cent of firms investing in R&D.

Introduction of new products, process, logistics,

maintenance systems and structures was in the

middle (around 72, 60, 40, 68 and 67 respectively)

(see Table 5).

Figure 1: Size of business in each industry.

3.2.7 Other Services (Ind5)

83 businesses were included in the other services

category (ind5) with an average age of around 26

years, with sales proceeding mainly from national

activity (more than 90 per cent). The majority of

businesses were classified as small or medium (see

Figure 1) and the average growth was 5,25 per cent

(see Table 5).

Around 73 per cent of enterprises had introduced

new products or services, and of these, 78,7 were

new to the market (the highest figure). Investment in

R&D was medium (32,5 per cent) and investment in

formal training was medium to high (almost 70 per

cent). The other innovation variables were as

follows: new processes around 56, new logistics

around 45, new maintenance around 53, new

structures around 58 and new marketing methods

around 55 (see Table 5).

0 20406080100

Ind1

Ind2

Ind3

Ind4

Ind5

Ind6

small

medium

large

Analyzing a Knowledge Country - How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?

129

3.2.8 Retail (Ind6)

65 businesses were included in the retail industry

(ind6) with an average age of around 18 years (the

lowest) and where sales proceeded mostly from

national activity (more than 96 per cent). The

majority of businesses were classified as large (see

Figure 1) and average growth was 6,13 per cent (see

Table 5).

This industry stood out in investment in formal

training (80 per cent of businesses). 76,9 per cent of

businesses had introduced new products or services

and of these, 64 per cent were new to the market. In

addition, the retail industry made the largest

investments in introducing new logistics and

maintenance systems (around 49 and 69

respectively).

3.2.9 Differences between Industries

Based on previous information, and despite

differences between industries, the Swedish

businesses surveyed were proactive with respect to

innovation, with only around 9 per cent of the

sample not carrying out some activity linked to

innovative activity or R&D investment. All

remaining firms carried out at least some other

innovative activity.

With regard to differences between industries,

Firms in the machinery industry are ranked first in

introducing new products or services, and the

majority of these products or services were also new

for the market as a while. In general, analyzing all

the innovative variables, this industry could be

considered as overall the most innovative, because it

also ranks first in introducing new processes, and

structures and investment in R&D was also highest.

The remaining variables were also in the medium to

high range.

Another industry very much interested in

innovation activities was the retail industry: it has

introduced the most new logistics and maintenance

systems and made the highest investment in formal

training. It also ranked as medium to high on the

remaining variables.

However, the fabricated metal industry was

considered least innovative in comparison: in

general, it had introduced fewer innovations

(products, services, process, logistics, maintenance

systems, structures and marketing). In addition, it

had the lowest percentage of marketing innovations

and investment in formal training was also the

lowest.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In the present day where knowledge is presented as

an essential tool for achieving competitive

advantages, this paper has analysed how Sweden

manages innovation. Sweden makes for an

interesting case study because it is considered a

knowledge country, and therefore an example for

others.

In order to analyse the Swedish strategy, this

paper summarised the strategy of the Swedish

government and provided an analysis of how

individual companies manage their internal process

of innovation. As a result of this analysis certain

conclusions were obtained:

The Swedish government has a proactive

vision for innovation, highlighting its

importance for the future and planning

actions within an innovative strategy.

The Swedish government strategy has a clear

aim: to contribute towards a climate with the

best possible conditions for innovations in

2020.

The presence of such a plan indicates that

Sweden has thought about the innovation

process, and gives the very positive

impression that they have taken the first step

in order to achieve the goals.

Analysing the behaviour of individual firms ,

there were no differences between regions in

how innovation was managed

However, significant differences were

obtained between industries in how this was

achieved.

The Machinery industry was found to be the

industry with the most proactive vision for

innovation.

The Retail industry also proved to be an

innovative industry.

The fabricated metal industry was considered

the least innovative in this comparison, based

on the analysis of relevant innovation activity

variables

Although there were differences between

industries, the majority of Swedish

businesses had a proactive vision linked to

innovative activity and/or R&D investment.

This study and its findings prove to be

interesting both for Sweden and other countries. .

For Sweden the contributions are clear: the analysis

has presented the situation for the country in 2013,

therefore it provides feedback for the government on

their strategy. This analysis is also useful because

Sweden is considered an example of “a knowledge

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

130

country” that serves as an example and a reference

for other regions.

The study has certain limitations. First, it is a

static analysis because it includes data form only a

single year: 2013. In addition, the role for public

administration has only been analysed only from a

theoretical viewpoint. With regards to the last

limitation, a future research possibility would be to

expand this research by carrying out an empirical

analysis of innovation in Sweden more generally. In

addition, it would be useful to do another analysis in

2020, the time horizon considered, and make a

comparison between the situation before and after

the implementation of the strategy. Another

limitation relates to the services industry, which was

not examined in much detail in this article due to a

lack of relevant data, despite its importance to the

wider economy. Another future possibility for

research would be an exploration of this industry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the World Bank

Database and Enterprise Surveys for allowing access

to the data.

REFERENCES

Arango Londono, J. F., 2012. La gestion de la innovación

como un ecosistema heterogéneo y estructurado.

Cuadernos de Gestion, 12: 125-137.

Camio, M. I., Rebori, A., Romero, M. C., 2014. Gestion

de la innovación. Estudio de casos en empresas de

software y servicios electrónicos de la zona de

influencia de la UNICEN, Argentina. Revista de

Administraçao e Innovaçao, 11(2): 3-50.

Formichella, M. M., 2005. La evolución del concepto de

innovación y su relación con el desarrollo, Working

paper, Estacion Experimental Agropecuaria Integrada

(convenio MAAAyP-INTA).

Gondora, G., Garcia, D., Madrid, A., 2010. Efecto del

apoyo publico sobre el comportamiento innovador y el

rendimiento en PYMES. Revista de Ciencias Sociales

(RCS), XVI(3): 400-417.

Government Offices of Sweden, 2016, The Swedish

Innovation Strategy. http://www.government.se/

contentassets/cbc9485d5a344672963225858118273b/t

he-swedish-innovation-strategy (accessed: 7 May

2016).

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R., Black, W., 1995.

Multivariate data analysis, Prentice Hall. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ.

Herkema, S., 2003. A complex adaptative perspective on

learning within innovation projects, The Learning

Organization, 10(6), 340-346.

Huber, F., 2013. Knowledge-sourcing of R&D workers in

different job positions: contextualising external

personal knowledge networks, Research Policy, 42:

167-179.

Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., Olander, H., Blomqvist, K.,

Panfilii, V., 2012. Orchestrating R&D networks:

Absorptive capacity, network stability and innovation

appropriability, European Management Journal, 30:

552-563.

Liao, C., Wang, H-Y, Chuang, S-H, Shih, M. L., Liu, C-C,

2010. Enhancing knowledge management for R&D

innovation and firm performance: An integrative view,

African Journal of Business Management, 4(14):

3026-3038.

Luengo, M. J., Obeso, M., 2012. Innovation as value key:

the Spanish case, Proceedings of the 7

th

European

Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship,

Santarem, Portugal.

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H., 1995. The knowledge-creating

company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation, Oxford University Press. New

York.

OECD, 2010. The OECD Innovation Strategy; Getting a

Head Start on Tomorrow. http://www.oecd.org/sti/

inno/theoecdinnovationstrategygettingaheadstartontom

orrow.htm (accesed 3 May 2016).

Oslo Manual, 2005. Guidelines for colecting and

interpreting innovation data. OECD, Eurostat.

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/

oslo-manual_9789264013100-en (accessed 15 May

2016).

Sakaiya, T., 1991. The knowledge value revolution or a

History of the future, Kodansha. Tokio.

Sarabia, M., Obeso, M., Sarabia, J.M., 2012. How do

European countries manage their knowledge? A cross

analysis of investment and performance, Innovation:

Management, Policy and Practice, 14(1): 129-142.

Schiuma, G., Lerro, A., 2008. Knowledge-based capital in

building regional innovation capacity, Journal of

Knowledge Management, 12(5): 121-136.

Schumpeter, J. A., 1934. The theory of economic

development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit,

interest and the business cycle, Harvard University

Press. Cambridge, MA.

Von Krogh, G., 2012. How does social software change

knowledge management? Toward a strategic research

agenda, The Journal of Strategic Information Systems,

21(2): 154-164.

World Bank, 2016. http://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed

1 May 2016).

Analyzing a Knowledge Country - How is Sweden Managing its Innovation Process?

131