Model-based Strategic Knowledge Elicitation

J. Pedro Mendes

Centre for Marine Technology and Ocean Engineering (CENTEC),

Instituto Superior Tecnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords:

Knowledge Elicitation, Mental Models, Strategic Problems, Problem Symptoms, Problem Dynamics, Strategy

Implementation.

Abstract:

Strategic problems are difficult. They often only exist in the mental models of some top managers. They are

typically too vague to be given a precise meaning, yet at the same time concrete enough to cause discomfort.

They cannot be discarded but they cannot be tackled either because the means for diagnostic and solution

are lacking. The body of knowledge of strategy offers little help, in the sense that a set of tools for strategic

problem solving does not exist, in practice. In science and engineering, problem solving is model-based. In

the past, the social sciences and management have discarded model building due to its inherent difficulties.

Today, the means are available to elicit knowledge about the symptoms of strategic problems, create a model

to obtain a solution, and produce an implementation plan.

1 INTRODUCTION

In service or manufacturing organizations, informa-

tion about delivery delays or quality issues is fre-

quently handled down the ranks, according to well-

understood business policies. Problems are to be

solved right away, and managers at all levels are al-

legedly there for that purpose. Unsolved problems are

a threat, and those managers will do their best to hide

their existence. Eventually, top management may get

rumors of cost overruns, but there will be no reason

to change policies if some explanation can quickly

be rationalized. Top managers may only acknowl-

edge there is a problem when outright failures can no

longer be disguised. Then, as they start to feel un-

comfortable, something needs to be done.

Problems are noticeable through their symptoms,

but symptoms cannot be confused with problems.

Sometimes symptoms must be dealt with immedi-

ately, fully realizing there must be some underlying

reason for them but also knowing that searching for

that reason is a luxury that cannot be afforded. Con-

sider the familiar example of the kid with fever. The

fever must be brought down, but once the symptom is

gone its causes may be difficult to trace. If there are

recurring symptoms, the physician will ask questions

to elicit knowledge about them. Interviewing is the

most common knowledge elicitation technique, in this

case used to translate the patient’s mental model into a

diagnostic. A diagnostic is yet another model, which

will be validated through further tests and checks.

Keeping a log of the symptoms, even if in the

mind, is key to establishing reference modes for prob-

lem behavior. Without at least an implicit description

of how symptoms evolved over time, no problem is

ever acknowledged. We all believe we can solve prob-

lems, but only the problems whose nature we under-

stand. Early in our lives, the problems were given to

us. We now consider them simple, but their answers

only came if we applied the right procedures. In fact,

the chosen procedure coerces the nature of the prob-

lem. Academia keeps reinforcing this pattern: we

have financial problems, marketing problems, and so

forth. Most problems in organizations are dealt with

by executing procedures established by policy.

Problems that defy policy are difficult to acknowl-

edge (Argyris and Sch

¨

on, 1978). Devising policies to

cope with emerging problems is the role of strategy.

A strategy begins to unfold when top managers start

feeling uncomfortable about some problem. At that

point, the diagnostic consists of rightly capturing the

problem symptoms. The solution consists of identi-

fying what procedures need to be stopped or created

from scratch, where the sequence of steps for doing

so is called implementation. Therefore, the challenge

for knowledge management research is eliciting prob-

lems early, at forming stage, rather than waiting for

them to creep up and become serious.

228

Mendes, J.

Model-based Strategic Knowledge Elicitation.

DOI: 10.5220/0006082102280234

In Proceedings of the 8th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2016) - Volume 3: KMIS, pages 228-234

ISBN: 978-989-758-203-5

Copyright

c

2016 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 A Recurring Issue

Strategic management topics carry a certain glamor

and are quite popular among business students. The

classroom problems covered are challenging and gen-

erate ample discussion. Nevertheless, business strat-

egy implementation remains problematic, perhaps

since the inception of the concept. Because this fact

remains mostly unacknowledged, we keep producing

strategies, and we keep believing we follow them, but

we actually rarely describe how to implement them.

One might think that strategic management prac-

titioners would know better. The promise of strate-

gic management is to identify what is important to

do now in view of intended future performance. And

yet, most practicing strategists don’t seem to follow

through the implementation of their strategies. With-

out proper implementation, no claims can be made

about the quality of a strategy. Unfortunately, at the

end of the day, companies keep struggling with how

to make their intentions show up in the bottom line.

The worst case scenario is when strategy theory

becomes akin to ”the emperor’s new clothes”. When a

strategy fails, executives and managers dare not blame

the failure on the approach they use, seeing as others

are seemingly following the same approach and al-

legedly doing well. Successive companies spend for-

tunes to buy or devise strategies that never produce the

intended results, sometimes even the opposite. Re-

peatedly failing to produce the intended results re-

veals a bankrupt approach.

2.2 Approach

Blaming failed strategies on difficult times, bad man-

agement or bad implementation is tempting, but the

argument does not hold water. According to Warren

(2012), both the theory and the practice of strategy

are seriously flawed. Adcroft and Willis (2008) ex-

plained that the reason is because knowledge trans-

fer from academia to practice is flawed. Thomas

et al. (2013) concurred, stating that the dominant

concern of academia appears to be a need for self-

justification rather than practical application. There-

fore, left mostly on their own, practitioners built a less

than flattering track record (e.g. Craig, 2005; Kihn,

2009; O’Shea and Madigan, 1998; Pinault, 2001).

Isaac Newton is credited for having said “If I have

seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of gi-

ants.” The strategic management body of knowledge

contributes little to understand why people rely on

strategies whose implementation keeps failing. To

avoid this syndrome, a mathematical metaphor from

Kurt G

¨

odel’s incompleteness theorems (about inher-

ent limitations of formal systems) suggests that one

should search outside the current body of knowledge

to deal with the limitations of strategic management.

This possibility is supported by Johansson (2006),

who argued that intersectional innovations, combin-

ing different knowledge sources, create opportunities

for research and teaching. This paper uses key histor-

ical references to provide a contribution from the sys-

tems sciences to strategic knowledge. Some funda-

mental principles, that were available since the birth

of the field, have apparently been overlooked or for-

gotten by strategy makers.

3 THE SYSTEMS SCIENCE VIEW

OF STRATEGY

3.1 Origins of Strategy in Systems

Science

Engineering design and construction relies on find-

ing solutions to mathematical models that incorporate

knowledge about relevant laws of nature and desired

system properties. For a set of initial conditions and

environmental parameters, those solutions depict the

characteristic behaviors of the system as functions of

time, and show how the system can evolve in response

to different inputs. A model with good predictive

power cannot be derived when knowledge about sys-

tem properties is scarce. Then again, without such

knowledge, one strategy is as good as the next.

Strategy practice doesn’t use mathematical mod-

els because management theory seldom uses mathe-

matics to build knowledge about system properties.

The common belief in the social sciences that useful

models are descriptive, without predictive capabili-

ties, was acknowledged early in an article published

by the ”Society for General Systems Research” Ar-

row (1956). Adding to the proof that systems knowl-

edge was part of a manager’s background, the influ-

ential theorist Chester Barnard was a member of the

Society.

In those early days, general systems and cybernet-

ics authors were seeing common feedback dynamics

properties across disparate knowledge domains, quite

different from engineering or physics. (The term ”cy-

bernetics” was probably intended to interest an in-

terdisciplinary audience in the mathematical model-

ing background of control theory.) Among those au-

thors was von Bertalanffy (1968), from the Psychi-

atric & Psychosomatic Research Institute at Univer-

Model-based Strategic Knowledge Elicitation

229

sity of Southern California and one of the founders of

the Society.

Another early relevant author was Ashby (1956),

trained as a Clinical Psychiatrist but landing with a

double appointment at the Departments of Biophysics

and Electrical Engineering of the University of Illi-

nois. Ashby proposed the Law of Requisite Variety,

saying that a controller must have at least the same

number of states as its target system. This was a fun-

damental result for engineering. In face of an arbi-

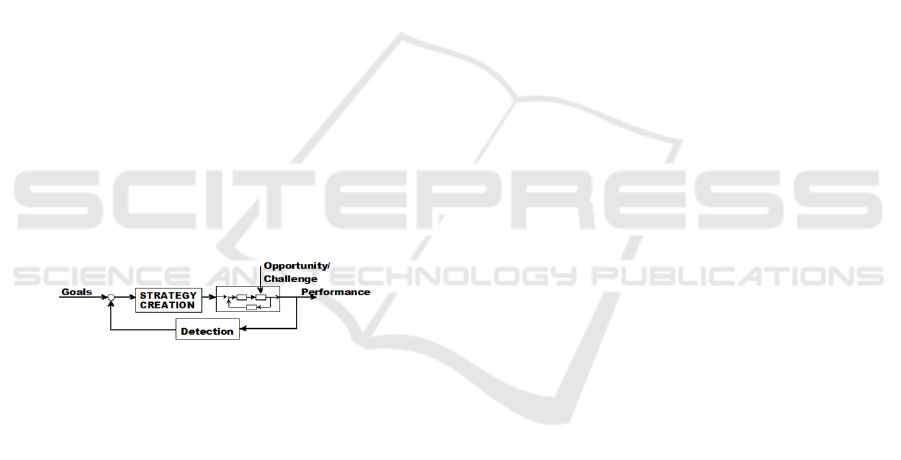

trarily large variety of disturbance inputs (Figure 1),

a system’s output only behaves according to its ref-

erence input if its controller follows good enough a

model to produce at least an equally large variety of

counteractions.

This law is fundamental for strategic thinking. As

referred at the outset of section 2.2, blaming failure

on difficult times or something else is always easy, in

hindsight. Since the mid 1950s, it was known that a

strategist attempting to oppose the organizational en-

vironment without at least an equally vast repertoire

of actions was doomed to fail. Yet this principle is

ignored by current strategists, which leads to the fol-

lowing:

Proposition 1: strategy makers confined

to data analyses and to outguessing their envi-

ronment miss the chance to create procedures

that can face disturbances.

Figure 1: Basic control loop as a strategic management

metaphor.

3.2 Models and Systems

Another reason why strategy theory doesn’t use math-

ematical models to increase knowledge about system

properties lies in the common misperception from

social sciences that the complexity of issues is an

impediment to finding useful solutions. Engineer-

ing copes with complexity by solving increasingly

sophisticated mathematical models. For instance,

work never ceased after Alexander Graham Bell’s

1876 patent for the electric telephone. Bell him-

self and Thomas Edison were earlier pioneers. As

interest grew, problems brought by increasing tele-

phonic traffic became more complex. The solution

of newer mathematical models successively led engi-

neers from direct connection to manual switchboards

and to worldwide switching.

Complex challenges require sophisticated solu-

tions. System Dynamics authors distinguish two

kinds of complexity. Combinatorial or detail com-

plexity occurs when many variables can take many

values. Dynamic complexity occurs when effects

dont directly follow causes in time and space. Be-

sides these, there is a third kind, equally important for

strategy implementation: communication complexity

occurs when uncertainty in task execution calls for

intensive information exchange among participants.

The mathematical relationship between uncertainty

and information was established back then by Shan-

non (1948).

Regardless of how complex a challenge may be,

strategists believe their solutions are enough for a

strategy to succeed. In the absence of a powerful sys-

tems description language, faulty hierarchical com-

munication is often blamed for strategy implementa-

tion failures. Furthermore, most modern strategy text-

books also concur that the management of strategy

implementation is more art than science. This near

euphemism at least acknowledges the limitations of

the science principles in use in today’s practice, which

leads to the following:

Proposition 2: strategy makers who over-

look science and proper description tools must

live every day with the risk that resulting out-

comes may be detrimental.

In the early 1940s, at Bell Telephone Laborato-

ries, the discipline of coping with complexity be-

came known as Systems Engineering. The challenges

to communications engineering had grown past the

models of physical systems to include social con-

cerns such as user behavior. Integrating knowledge

from different technical domains was already difficult

within engineering alone, because different special-

ties used different vocabulary and graphical notations.

In other fast growing fields, pioneers faced with iden-

tical problems felt compelled to come up with differ-

ent representations (Olle et al., 1982).

Over time, different representations evolved into

the Systems Modeling Language (SysML), which be-

came a standard in 2007 (Friedenthal et al., 2015).

SysML addresses many known modeling difficulties.

Besides technological sophistication, systems models

can now represent the richness of business and man-

agerial interactions by taking into account the charac-

teristics and behaviors of human users and operators.

SysML models can describe personnel, facilities,

process, and performance requirements for a wide

range of systems. They also contribute to better com-

munication between people of different backgrounds.

The implication for strategy implementation is that

procedures can be richly communicated in SysML us-

ing terminology germane to each area of expertise.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

230

4 THE DESIGN FRAMEWORK

VIEW OF STRATEGY

4.1 A Theory of Designed Strategy

Engineering is the design and construction of systems

to meet performance goals. The Accreditation Board

for Engineering and Technology defines ”design” as

the process of devising a system, component or pro-

cess to meet desired needs. Engineering design is iter-

atively revised to remove deviations from the specifi-

cation. Then, using constructive methods, implemen-

tation is made according to design.

Relying on quantitatively verifiable intentions is

the fundamental difference that separates strategy de-

sign from the ad-hoc adoption of whatever tools are

at hand. An example of a handy tool is the widely

used Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan and Norton, 1992).

Created for performance monitoring and control, it

is often misused for strategy specification or design.

However, even in engineering, the best construction

and operation practices (means) will not yield results

in the absence of design goals (ends). This leads to

the following:

Proposition 3: strategy makers who con-

fuse ends with means increase the risk of im-

plementing the wrong procedures.

In turn, ends are stated as specifications, which are

formal quantitative descriptions of required function-

ality and behavior. Specifications describe what a sys-

tem does when responding to inputs, but not how the

system does it and much less how those inputs orig-

inate. Organizational inputs are internal or external

disturbances. Seeing an organizational strategy from

the perspective of a system that can be designed leads

to the following:

Concept 1: the specification of a strategy

quantifies performance metrics for desired be-

havior in response to inputs.

All systems take inputs and deliver outputs. The

output of a strategy is the set of policies (procedures)

that cover expectable system behaviors, often includ-

ing rules for handling exceptions in regular transac-

tions. Like all complex systems, organizations are

sensitive to external events, often of unknown ori-

gin and nature. A common practice to cope with un-

certainty is to brainstorm around hypothetical events

and build scenarios accordingly. These scenarios may

have the merit of making people think about issues,

but they help solve no real problems whatsoever. To

actually solve those problems, competitive challenges

and external events need to be thought of as just alter-

native system inputs. What matters is not the nature

of those inputs but their impact on the system, and

the consequences thereof. This thinking leads to the

following:

Concept 2: behavior-based scenarios de-

scribe a system’s response to changes trig-

gered by unspecified arbitrary events.

Over the years, performance standards and other

engineering principles have been extended from phys-

ical to software systems, and then to management

systems. Kurstedt et al. (1988) defined a manage-

ment system as the set of responsibilities of a manager

bounded as a system. They generalized the definition

of manager to anyone who uses information to make

decisions that result in changes in the managed oper-

ations performance. Faced with external events, man-

agers make decisions and issue policies and directives

to control outputs. This leads to the following:

Concept 3: the output of a management

system is the net change in the operations per-

formance that results from implemented poli-

cies.

A common dictionary description of ”design” is

”to plan the form and structure of”, whereas ”to plan”

refers to ”any method of thinking out acts and pur-

poses beforehand”. Therefore, to design is to pre-

dict what a system will do and what behavior it will

display when properly built and operated in its envi-

ronment. The term ”properly” implies the adoption

of engineering principles throughout the system life-

cycle. Too many strategies are put together not on a

predictive basis, but rather on a wishful thinking ba-

sis. Designed strategies produce systems that respond

to external events (disturbances, inputs) with the in-

tended behaviors (performance). In turn, this leads to

the following:

Concept 4: to design a management sys-

tem is to think out beforehand the actions re-

quired to respond to external events and meet

specifications.

4.2 Strategy Performance

According to Wernerfelt (1984), the result of strategy

implementation is the series of business transactions

to acquire and dispose of organizational resources.

Good implementation covers the whole strategy life-

cycle for risks of overspending money and time while

performing those transactions. In turn, Fooks (1993)

described an approach for improving life-cycles by

reducing implementation cost and time. Similar to

the concept of product life-cycle, a strategy life-cycle

starts when a challenge is acknowledged and finishes

Model-based Strategic Knowledge Elicitation

231

when the challenge is considered overcome. Strategy

performance is the effectiveness and efficiency with

which the management system handles disturbances.

Renowned military strategist Col. John Boyd

showed how mental patterns or concepts of mean-

ing must be questioned and reshaped to cope with

a changing environment (Osinga, 2005). Boyd ex-

plained his well-researched theory in a two-day in-

tensive briefing, which he may have delivered some

1500 times but never published. He held that contin-

ually shortening a four-step observe-orient-decide-act

cycle (OODA loop) is critically important to outper-

forming opponents. The OODA loop is inspirational

to manage a strategy life-cycle and has many similari-

ties with the plan-do-study-act cycle (Deming, 1952).

The capability to continually evolve mental pat-

terns by detecting and correcting errors is called

learning. Argyris and Sch

¨

on (1978) showed how at-

titudes and beliefs influence the way people learn to

identify and cope with problems. They distinguish

single-loop learning, which is repeatedly solving sim-

ilar problems within prescribed goals, from double

loop learning, which is modifying a goal given previ-

ous experience. Single-loop learning is effective for

operational control (Figure 2). Double-loop learning

is a distinct capability that relies on open communica-

tion up the ladder, which gives managers the feedback

required to adapt the business model to changes in the

internal and external environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Acknowledged challenges impact single- and

double-loop learning.

The function of hierarchical control is to enforce

current policy, maintaining desired behavior in face of

successive challenges. However, there is a point when

current policy can no longer tackle perceived chal-

lenges, and a strategy must be devised to deal with

them. The timely decision to replace current policy

requires the capability to detect emerging problems,

which may lie beyond the scope of the strategy as

originally conceived. The problem detection process

represents the outer double-loop view of how the in-

ner single-loop management control system handles

inputs.

4.3 Argument

The likely reason why business strategy implementa-

tion still remains an issue is the lack of a sound body

of knowledge that supports going from inception to

practice. Strategy is all about living tomorrow with

the consequences of today’s decisions. Faced with

the need to state, or specify, the outcomes of deci-

sions, strategists know only how to be vague, hide be-

hind uncertain or turbulent times, and blame whatever

mishaps may arise on bad implementation. They can

do little else given the tools they have.

Weick (1996) warned against holding so dearly

to the tools of the trade that one may lose perspec-

tive of whether they still serve their purpose. Strat-

egy is preparing today for what the future may bring.

For strategists to be held accountable for the outcome

of their decisions, they not only need new tools but

also a new paradigm for using them. The paradigm

shift is focusing on the consequences of events, in-

stead of on the events themselves (proposition 1). In

turn, the consequences of events can be identified us-

ing system-based description tools (proposition 2).

The systems view looks at behaviors over time

rather than at point figures (concept 1). Considering

that behaviors are a systems response to inputs, the

paradigm shift consists of building future scenarios

around a necessarily finite number of consequence be-

haviors rather than around guesswork over the count-

less events that may originate them (concept 2). Then,

responding to each scenario calls for adopting policies

that drive the desired behaviors (concept 3).

The systems view of strategy also fosters im-

proved preparedness by supporting the creation of

policies that take into account the consequences of

unforeseen events (concept 4). This approach is quite

foreign to current teaching and strategy frameworks.

But strategy is about the means to reach desired ends,

not to be confused with the means to reach the strat-

egy itself (proposition 3).

5 KNOWLEDGE ELICITATION

5.1 Implications

A business strategy is often backed up by a busi-

ness plan. Ideally, this plan describes how the op-

erational and financial objectives of the business will

be achieved. In practice, the business plan consists

mainly of a financial forecast driven by market eval-

uation. The typical business plan may include sec-

tions describing physical operational needs, such as

location, facilities and equipment, as well as required

people skills and schedules. However, the traditional

business plan is seldom a true plan, in the sense that

its purpose is to secure approval and financing rather

than to provide an execution blueprint.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

232

Blueprints are the outcome of engineering design

and a necessary means to share conceptual views

when building physical systems. Business strategies

deserve no less care. Under this metaphor, a strat-

egy blueprint consists of a comprehensive sequence

of activities supported by proven modeling tools. A

strategy blueprint contains the functional and behav-

ioral description of the actions that lead to the desired

results. The use of this blueprint as a communication

and sharing tool for the whole organization becomes

a benefit that is far from trivial.

Pfeffer (1993), who received the Academy of

Management Review’s Best Article Award that year,

said of organizational science that the field was losing

identity and drifting toward an ”anything goes atti-

tude, which seems more characteristic of the present

state” (p. 616). Strategic management may be falling

into the same trap. Warren (2012) already painted

a dark future for strategy, unless methods change.

A framework for methods change was suggested by

Mendes (2011), although at a price: new methods

need to be taught at school before they enter the main-

stream, which may be difficult if they go against the

current paradigm.

The main obstacle to overcome is teaching for-

mal modeling methods in business schools. Those are

mandatory for a proper diagnostic of problems. Not

too long ago there was a popular TV show titled Dr.

House. The main characters were a team of diagnostic

doctors that, in spite of sophisticated analysis meth-

ods, would always make two errors in each episode

before finally saving the patient. But even as they

were making mistakes, they were learning and cor-

recting their mental models. Currently, most strategic

problem solving methods rely not on models of the

problem, but on causal brainstorming and root-cause

analysis, which are ill-suited for the purpose (Mendes

et al., 2016).

5.2 Value

System Dynamics is probably the best strategy mod-

eling and diagnostic tool available. Its creator, Jay

Forrester, understood the effect of time delays and de-

cision amplification on the dynamic behavior of man-

agement systems. Forrester (1958) showed that the

pattern of information-feedback relationships among

management system components was far more impor-

tant to explain behavior over time than the compo-

nents themselves or any external events. This arti-

cle summarized his 1961 book, which is still in print

without revision.

Forrester created both a graphical notation and a

digital simulation language to represent dynamic re-

lationships. In his terminology, structure is the pat-

tern of those relationships, not the hierarchical or

functional chain of command. All management sys-

tems have a structure, whether designed or emer-

gent, known or implied. Changes to the structure can

be tested with a simulation model tuned to correctly

replicate a behavior that is specified upfront.

This capability to design and test a structure that

behaves as specified is a relevant addition to the strat-

egy designers toolkit. Simulation also uncovers unin-

tended consequences and suggests ways to cope with

them. However, powerful as it is, System Dynam-

ics never left the academic arena and remains in the

realm of specialists. Even for them, knowledge elici-

tation has been an issue (e.g. Ford and Sterman, 1998;

Vennix et al., 1992).

Ultimately, System Dynamics was never mas-

sively adopted because the solutions it produces must

be interpreted, and the bridge to implementation is not

straightforward. In the kid with fever example, the

family doctor or general practitioner was the trans-

lator between the parents and the medical specialist.

System Dynamics needs its translators. Those make it

easy to create a System Dynamics model and later, af-

ter a diagnostic and solution are available, help trans-

late back to managerial terms what needs to be done.

Mendes et al. (2016) described in detail the first step

in this strategy formulation process, the use of SysML

for problem knowledge elicitation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to this paper was partly funded

by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Tech-

nology (FCT - Fundac¸

˜

ao para a Ci

ˆ

encia e Tecnolo-

gia) under its annual funding to the Centre for Marine

Technology and Ocean Engineering (CENTEC). The

author thanks Marco DiMaio for suggesting the topic.

REFERENCES

Adcroft, A. and Willis, R. (2008). A snapshot of strategy

research 20022006. Journal of Management History,

14(4):313–333.

Argyris, C. and Sch

¨

on, D. A. (1978). Organizational Learn-

ing. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

Arrow, K. J. (1956). Mathematical models in the social sci-

ences. In von Bertalanffy, L. and Rapoport, A., edi-

tors, General Systems: First Yearbook, pages 29–34.

Society for General Systems Research.

Ashby, W. R. (1956). An Introduction to Cybernetics. Chap-

man & Hall, London, UK.

Model-based Strategic Knowledge Elicitation

233

Craig, D. (2005). Rip-off!: The scandalous inside story of

the management consulting money machine. Original

Book Company, London, UK.

Deming, W. E. (1952). Elementary principles of the statis-

tical control of quality: a series of lectures. Nippon

Kagaku Gijutsu Remmei, Tokyo, JP.

Fooks, J. H. (1993). Profiles for performance: Total qual-

ity methods for reducing cycle time. Addison-Wesley

Longman, Reading, MA.

Ford, D. N. and Sterman, J. D. (1998). Expert knowledge

elicitation to improve formal and mental models. Sys-

tem Dynamics Review, 14(4):309–340.

Forrester, J. W. (1958). Industrial dynamicsa major break-

through for decision makers. Harvard Business Re-

view, 36(4):37–66.

Forrester, J. W. (1961). Industrial Dynamics. MIT Press,

Cambridge, MA.

Friedenthal, S., Moore, A., and Steiner, R. (2015). A Prac-

tical Guide to SysML: The Systems Modeling Lan-

guage. Elsevier, Waltham, MA.

Johansson, F. (2006). The Medici effect: What elephants

& epidemics can teach us about innovation. Harvard

University Press, Boston, MA.

Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced score-

card - measures that drive performance. Harvard Busi-

ness Review, 70(1):71–79.

Kihn, M. (2009). House of lies: How management con-

sultants steal your watch and then tell you the time.

Business Plus, New York, NY.

Kurstedt, H. A., Mendes, P. M., and Lee, K. S. (1988). Engi-

neering analogs in management. In Proceedings of the

Ninth Annual Conference of the American Society for

Engineering Management, pages 197–202. ASEM.

Mendes, J., Carreira, A., Aleluia, M., and Mendes, J. P.

(2016). Formulating strategic problems with Systems

Modeling Language. Journal of Enterprise Transfor-

mation, 6(1):23–38.

Mendes, J. P. (2011). Moving forward in organizational

science. http://www.nsf.gov/sbe/sbe 2020/2020 pdfs/

Mendes Pedro 190.pdf. [Accessed: Sept, 2016].

Olle, T. W., Sol, H. G., and Verrijn-Stuart, A. A. (1982). In-

formation Systems Design Methodologies: A Compar-

ative Review. Proceedings of the IFIP WG 8.1 Work-

ing Conference on Comparative Review of Informa-

tion Systems Design Methodologies. North-Holland,

Amsterdam, NL.

O’Shea, J. and Madigan, C. M. (1998). Dangerous Com-

pany: Management Consultants and the Businesses

They Save and Ruin. Penguin Books, London, UK.

Osinga, F. P. B. (2005). Science, Strategy and War: The

Strategic Theory of John Boyd. Eburon Academic

Publishers, Delft, NL.

Pfeffer, J. L. (1993). Barriers to the advance of orga-

nizational science: Paradigm development as a de-

pendent variable. Academy of Management Review,

18(4):599–620.

Pinault, L. (2001). Consulting Demons: Inside the Un-

scrupulous World of Global Corporate Consulting.

Harper Paperbacks, New York, NY.

Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of commu-

nication. The Bell System Technical Journal, 27(July,

October):379–423,623–656.

Thomas, P., Wilson, J., and Leeds, O. (2013). Construct-

ing the history of strategic management: A critical

analysis of the academic discourse. Business History,

55(7):1119–1142.

Vennix, J. A., Andersen, D. F., Richardson, G. P., and

Rohrbaugh, J. (1992). Model-building for group de-

cision support: issues and alternatives in knowledge

elicitation. European Journal of Operational Re-

search, 59(1):28–41.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General Systems Theory.

George Brazziler, New York, NY.

Warren, K. (2012). The trouble with strategy: The brutal re-

ality of why business strategy doesn’t work and what

to do about it. Strategy Dynamics Ltd, Princes Ris-

borough, UK.

Weick, K. E. (1996). Drop your tools: An allegory for orga-

nizational studies. Administrative Science Quarterly,

41(2):301–313.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm.

Strategic Management Journal, 5(2):171–180.

KMIS 2016 - 8th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

234