Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience

Relationships between Visitors’ Eye Movements, Audio Guide Contents,

and the Levels of Contentment

Kazumi Egawa

1

and Muneo Kitajima

1,2

1

University of Tokyo, Bunkyo, Tokyo, Japan

2

Nagaoka University of Technology, Nagaoka, Nigata, Japan

Keywords:

User Evaluation, User Experience, Cognitive and Conceptual Models, Eye Movements, Museum Novice,

Audio Guide.

Abstract:

Museums provide the opportunities of acquiring knowledge concerning artistic, cultural, historical or scientific

interest through a large number of displays. However, even if those masterpieces are visually accessible to

all the visitors, the background of these works of art is not necessarily acquired because the visitors do not

have enough knowledge to fully appreciate them. Audio guide is a commonly used tool to bridge this gap.

The purpose of this study is to gain understandings of relationships between visitors’ eye movements for

acquiring information by seeing, the contents of the audio guide that should help them to understand the

objects by hearing, and the levels of contentment from the museum experience. This paper reports the results

of an eye tracking experiment in which nineteen participants were asked to appreciate a variety of pictures

with or without audio guide, to fill in a questionnaire concerning subjective feelings, and to attend a follow-

up interview session. It is found that the participants could be classified into four categories, suggesting an

effective way of providing audio guide.

1 INTRODUCTION

Acquiring knowledge is an essential activity that all

people should conduct; in some cases, it is for ac-

complishing certain task goals, and in other cases, it

is not related with any concrete superordinate purpose

but “acquiring knowledge” itself becomes the goal of

people’s activities. In any cases, by accomplishing the

activity of acquiring knowledge, people should find

the feeling of satisfaction, or contentment, and the ac-

quired knowledge should contribute to establish new

connections in the existing network of knowledge in

their brains, which would become a basis for acquir-

ing a series of new knowledge in the future.

1.1 Acquiring Knowledge at Museum

In recent years, museum has been considered as one

of suitable places for learner-centered learning and

lifelong learning. This is because of the form of learn-

ing that is presented at museum. Museum is a build-

ing in which objects of artistic, cultural, historical

or scientific interest are kept and shown to the pub-

lic. People visit a museum building and approach an

object in which they are interested, stay a while in

front of the object to study it, then approach to an-

other. This process continues until they decide not to

do so. This style of learning is considered as “self-

paced learning”. It is an effective learning method

to improve performance (Tullis and Benjamin, 2011),

guided by their motivation. When the works of art in

the museum are displayed in such a way to facilitate

self-paced learning, it would make possible learner-

centered learning. A critical condition for lifelong

learning would be the maintenance of motivation of

learning. Museum setting provides a necessary con-

dition for it.

This paper focuses on experience at museum and

deals with the question how the activity of knowledge

acquisition is carried out at museum. Museum is the

place where a variety of valuable opportunities for ac-

quiring knowledge are provided to people. Museum

novices visit for the purpose of acquiring knowledge

about the works displayed there. The content of

knowledge about the works must not be general but

highly individual because the information concerning

the objects, which is general and accessible via expla-

nation boards, has to be integrated with the existing

Egawa K. and Kitajima M.

Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience - Relationships between Visitorsâ

˘

A

´

Z Eye Movements, Audio Guide Contents, and the Levels of Contentment.

DOI: 10.5220/0006119500170026

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2017), pages 17-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-229-5

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

17

network of knowledge in the person’s brain to become

his/her knowledge.

1.2 Comprehending Objects at Museum

with Seeing and Hearing

Comprehending objects displayed at museum is anal-

ogous to comprehending texts on a book. According

to the construction-integration theory of text compre-

hension (Kintsch, 1988; Kintsch, 1998), the cogni-

tive processes for comprehension involve two stages:

1) activation of knowledge to construct a knowledge

network that is associated with the representations re-

sulted from perception of the object a person is look-

ing at, which is an automatic activation process of rel-

evant knowledge stored in his/her long-term memory

for the perceived object, followed by 2) a network

integration process to obtain a coherent meaning of

the perceived object that is consistent with the current

context, which could be an automatic unconscious

process or a deliberate conscious process depending

on the level of difficulty involved in the comprehen-

sion process.

In some cases it is not necessary to activate ad-

ditional knowledge for gaining the feeling of com-

prehension if the object is familiar to him/her. In

other cases, however, it requires more cognitive steps

to fully comprehend the object by overpassing infer-

ences because the object is too difficult to gain an im-

mediate understanding. This paper deals with the lat-

ter case, and seeks a way to alleviate this difficulty by

timely providing audio guide, which should interfere

at the minimum with the visual modality of a museum

novice which is used by him/her heavily for observing

the object. The content of audio guide should acti-

vate necessary knowledge to comprehend the object

through another modality than visual. If the infor-

mation provided by audio should activate the part of

knowledge that is missing in the knowledge activated

by the visual information, the person is likely to reach

better comprehension state, that is not being able to

achieve otherwise.

1.3 Measuring Conscious/Unconscious

Processes in Comprehension

The processes of comprehending an object start with

the processes of observation, which could be con-

trolled either consciously or unconsciously, in other

words, they could be deliberate or automatic. It is

known that the processes controlling human activities

are dual, known as the dual-processing theory (Kah-

neman, 2003; Evans, 2003; Evans and Frankish,

2009; Evans, 2010). In addition, the working of long-

term memory should be regarded as autonomous,

which means that the memory reacts to the represen-

tation of perception automatically and it does not be-

have as a passive data-store, similar to a database sys-

tem that stores a huge amount of digital data (Kitajima

and Toyota, 2013; Kitajima, 2016).

Visual information processing starts with feeding

visual stimuli to the brain, followed by either un-

conscious or conscious information processing for

comprehending objects. Gaze points of a person

should indicate the visual information of the object

that might be used for further unconscious or con-

scious processing with automatic knowledge activa-

tion in long-term memory, that should contribute to

reaching comprehension of the object. Note that the

memory activation process is autonomous, not con-

trolled top-down by higher cognitive processes that

issue the command of retrieval of necessary portion

of knowledge.

The locations where the visitors are looking at,

i.e., the gaze points, are measured by using the eye-

tracking technology. If the network of knowledge is

activated sufficiently, he/she would gain the feeling

of satisfaction, or contentment, which is measured by

questionnaire or interview. This paper addresses the

possibility of facilitating knowledge activation via the

audio modality by providing audio guide, which is

subsidiary to the visual modality in appreciating ob-

jects at museum.

1.4 Purpose and Outline of the Paper

For the purpose of enhancing self-paced learning, this

paper studies the effect of audio guide on the levels

of contentment of museum novices by analyzing the

patterns of eye movements while appreciating objects

with or without audio guide. This paper starts with a

section describing a model of contentment in museum

experience and explaining visual information acquisi-

tion in museum experience. Then, the following sec-

tion describes an eye tracking experiment conducted

with nineteen museum-novice participants, who were

asked to appreciate a variety of paintings with or with-

out audio guide. Finally, the last section is presented

for describing the results of experiment and discus-

sion concentrating on the possibility of enhancement

of self-paced learning at museum for museum novices

with timely provision of audio guide.

2 MUSEUM EXPERIENCE

People visit museum to study objects they are interest-

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

18

ed in. It is carried out mainly by observing objects

through their eyes. As the results of their observation,

they have different levels of feeling of satisfaction, or

contentment. In the following subsections, content-

ment in museum experience and visual information

acquisition in museum experience are described.

2.1 Contentment in Museum

Experience

In the study of investigating elicitation of emotions

while viewing films, the following types of emotions

are considered (Gross and Levenson, 1995):

relief anger surprise

arousal sadness fear

interest tension pain

contempt disgust happiness

confusion embarrassment amusement

contentment

In the present study, it was assumed that similar emo-

tional reactions would occur while studying objects

at museum. These sixteen emotion types are used

to investigate the emotional structure of contentment

through the internal relationships among the emotion

types listed above. People visit museum for the pur-

pose of acquiring knowledge. They would have a

feeling of satisfaction on accomplishment of the goal.

This type of contentment is named “Cerebral Hap-

piness” which is accomplished by “The Intellect”,

one of seventeen happiness goals proposed by Mor-

ris (Morris, 2006). In the present study, the sixteen

emotional states that should occur in response to the

activity of observing objects, and the degree of Cere-

bral Happiness is measured by having the participants

fill in the questionnaire as shown by Table 1. Q1 is for

measuring emotional state and Q2 through Q9 are for

measuring Cerebral Happiness.

2.2 Knowledge Acquisition in Museum

Experience

2.2.1 Eye Movement in Museum Experience

Museum experience involves appreciation of objects.

Since most part of information is visual, eye move-

ments are important information to understand ap-

preciation behavior of museum visitors (Solso, 1996;

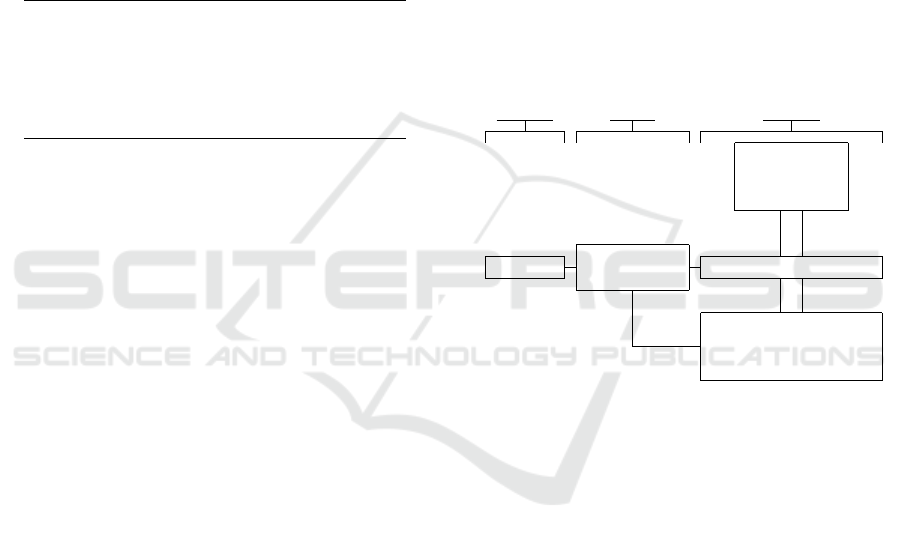

Yarbus, 1967b). Figure 1 illustrates the perceptual

and cognitive processes that are carried out in the

brain while appreciating objects. The appreciation

process goes as follows:

1. Perceives via vision the information conveyed by

painting that exists in the external physical world,

2. Detects visual features such as edges of the per-

ceived objects on the retina via optical processes,

and then transmits the results by electrical infor-

mation to the brain,

3. Associates the information processed in the visual

cortex with the knowledge stored in the cerebral

cortex to learn and/or estimate the objects, which

is called semantic processing,

4. Initiates eye movements and/or body movements

in response to the results of the semantic process-

ing.

The pattern of eye movements is an external parame-

ter that should reflect the intension or purpose of the

museum visitors (Yarbus, 1967a).

Physical

World

Eye

Brain

Experience

Learning

Evaluation

Painting

Optical

Processing

Semantic Processing

Processing movement

of the body

e.g., eye movements

- -

?

6

?

6

6

Figure 1: Cognitive Model (Solso, 1996).

Figure 1 illustrates a cyclic process of optical pro-

cessing, semantic processing, and motor processing,

i.e., eye movements. It is reported that the number

of cycles carried out for a single object depends on

the degree of the smoothness of learning of the ob-

ject, which is proportional to the length of time to

appreciate the object. The shorter the appreciation

time becomes, the less effective the museum novice

feels his/her learning progress (Okumoto and Kato,

2010). The appreciation time could be additionally

characterized by the change of the number of fixations

per unit time as appreciation behavior develops (Ja-

cob and Karn, 2003). This paper uses these factors

to characterize the museum novices’ appreciation be-

havior.

2.2.2 Using Audio Guide to Enhance Museum

Novices’ Experience

This paper focuses on the addition of audio guide,

which should have effect on the cycle introduced by

Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience - Relationships between Visitorsâ

˘

A

´

Z Eye Movements, Audio Guide

Contents, and the Levels of Contentment

19

Table 1: Evaluation items of subjective contentment.

Question Content

Q-1) For the following 16 kinds of emotions, please answer the strength that you have felt.

1) relief 2) anger 3) surprise 4) arousal

5) sadness 6) fear 7) interest 8) tension

9) pain 10) contempt 11) disgust 12) happiness

13) confusion 14) embarrassment 15) amusement 16) contentment

Q-2) I felt contentment from painting appreciation.

Q-3) It was my favorite painting.

Q-4) I found the meaning of the painting.

Q-5) I found the value of the painting was found.

Q-6) I wanted to know more about the painting.

Q-7) That study has developped new knowledge.

Q-8) I found where should I watch.

Q-9) I wanted actually to go to a museum of art.

Figure 1, especially during the semantic processing.

In order to deal with additional information channel, it

is necessary to consider the semantic processing with

a broader perspective in which the object is compre-

hended using various sources of information includ-

ing the directly perceived information as shown in

Figure 1.

Comprehension process involves knowledge acti-

vation process, triggered by perceptual information

acquired from the external environment, the appear-

ance of objects in museum in the specific context of

this paper, and currently activated knowledge through

the preceding cognitive processes including expecting

what to happen, reflecting on the past events, making

inferences of what comes next, etc. Comprehension is

achieved solely on the ground of the activated knowl-

edge.

In order to take into account the simultaneous,

asynchronous, and automatic activation of knowl-

edge through visual and audio information chan-

nels, resulting in a motor behavior of eye movements

after processing visual-audio information, this pa-

per adopts a comprehensive unified model, MHP/RT

(Model Human Processor with Realtime Constraints),

that is capable of simulating action selection pro-

cesses by underlying perceptual–cognitive–motor

processes and autonomous memory activation pro-

cess (Kitajima and Toyota, 2013; Kitajima, 2016).

The heart of the model is that coherent behavior in

the ever-changing environment is possible by syn-

chronization of automatic unconscious processes and

deliberate conscious processes by using activated por-

tion of memory with the process of resonance. One of

the case studies that applied MHP/RT to understand

people’s behavior was effectiveness of guidance in-

formation provided from a person sitting in the pas-

senger seat of a car to the driver who was not famil-

iar with the area he/she was driving (Kitajima et al.,

2009; Kitajima, 2016). The degree of effectiveness

was dependent on the contents of activated knowl-

edge of the driver. This paper considers that this is

a similar situation, where a museum novice would be

benefitted by the provision of audio guide while ob-

serving objects. When audio guide is provided timely,

it should be most effectively used to enhance the ex-

isting knowledge of the museum novice. The timing

would be characterized in relative to the perceptual

information that has been collected from the environ-

ment visually. It is assumed that the museum novice

should have a feeling of satisfaction if the information

provided though audio guide is smoothly integrated

with the then-activated knowledge to form more com-

plete knowledge, necessary for understanding the ob-

ject.

3 EYE TRACKING EXPERIMENT

An eye tracking study was conducted to understand

the effects of audio guide on the eye movement pat-

tern and the level of contentment of museum novices

who had intension of acquiring knowledge concern-

ing the objects used for the experiment.

3.1 Participants

Nineteen undergraduate students received course

credit for participation in the present study (all mu-

seum novices, 15 males, 4 females, average age =

21.4, SD = 0.6). All had normal or corrected-to-

normal vision and naive about the purpose of this ex-

periment.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

20

3.2 Stimuli

In order to simulate the activity of viewing painting,

six images of painting and three audio guides were

prepared with permission from the Bridgestone Mu-

seum of Art.

Three types of painting, i.e., portrait, landscape,

and abstract, were selected since people tend to look

at overt elements such as faces or objects. Landscape

has many elements, abstract has no elements, and por-

trait is between them. Two artistic works were used

for each type of painting, and one of the works was

presented with audio guide, and the other without it.

The set of stimuli with audio guide is called “audio

guided set”, and the one without audio guide, “no

assistance set” hereafter in this paper. Six paintings

were presented on a PC display one by one to each

participant.

3.3 Apparatus

Stimuli were controlled by Microsoft Powerpoint

2013 and were displayed on a 35 inch LCD moni-

tor in a testing room equipped with soft lighting and

sound attenuation. Eye movements were recorded us-

ing an eye mark recorder of nac (EMR-9), which had

a sampling rate of 60 Hz and a coverage area with the

horizontal angle of 44 degrees and the vertical angle

of 33 degrees. Participants were seated approximately

1100 mm from the monitor and made responses using

a mouse. Their chins were fixed using a chin support.

The experiment was carried out with one participant

at a time. Figure 2 depicts the arrangement of the ex-

periment.

Figure 2: Experiment environment.

3.4 Evaluation

The 25 items listed in Table 1 were evaluated by a

questionnaire using seven-point scale (1 = weak, · · · ,

7 = strong). Eye movements were evaluated using two

parameters; the viewing time and the frequency of fix-

ations.

Figure 3: A part of a questionnaire.

3.5 Procedure

First, participants were asked if they had understood

the purpose of the present study and agreed to partic-

ipate. After adjusting participant’s sitting posture and

fixing his/her chin, a calibration process was carried

out to ensure that the visual object and the eye mark

were located at the same position.

Before starting the experiment, each participant

was told to watch the displayed images carefully, to

do his/her best not to move his/her head, and to re-

move the image by clicking when he/she felt enough.

After that, a practice session was carried out with an

image.

Participants were explained the experimental pro-

cedure. In the experiment, all participants viewed

3 non-assisted images first and then followed by 3

audio-guided images. Participants were allowed to

have a break after finishing the non-assisted images

if they requested it. Three images in each section

were shuffled according to the latin square method.

The order was chosen by Table 3. When the partici-

pants clicked to remove each image, they were asked

to fill in a self-evaluate questionnaire shown by Ta-

ble 1. At the end of the experiment, participants were

interviewed about their reasoning in their evaluations

and whether they had seen the images before.

4 RESULTS

Due to the change in position of EMR head unit dur-

ing the break, participant 19’s eye movement cannot

be measured accurately. Therefore, participant 19’s

audio-guided data was removed from the analysis.

4.1 Contentment and Eye Movements

In this part, in order to clarify the relationship be-

tween contentment evaluation and eye movements,

the correlations between them were examined. Ta-

ble 4 shows the significant correlation coefficients be-

Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience - Relationships between Visitorsâ

˘

A

´

Z Eye Movements, Audio Guide

Contents, and the Levels of Contentment

21

Table 2: List of the stimuli used for the eye tracking experiment.

Type Artist Title Date Length of audio guide [sec.] ID

Portrait Sekine Shoji Boy 1919 - P

Portrait Fujishima Takeji Black Fan 1908-09 65 Pa

Landscape Asai Chu Laundry Place at Grez-sur-Loing 1901 - L

Landscape Paul Cezanne Mont Sainte-Victoire and Chateau Noir 1904-06 79 La

Abstract Paul Klee Island 1932 - A

Abstract Zao Wou-Ki 07.06.85 1985 87 Aa

Table 3: The presentation order of stimuli.

Non guided Audio guided

1 2 3 4 5 6

Pattern 1 L A P Aa Pa La

Pattern 2 P L A La Aa Pa

Pattern 3 A P L Pa La Aa

tween all evaluation items of subjective contentment

and items of eye movements. As shown, positive

emotions such as happiness and amusement mainly

have an effect on viewing time and frequency of fixa-

tions. And it shows the feeling of knowledge acquisi-

tion decreases as the frequency of fixations increase.

4.2 Audio Guide on Portraits

In this part, only two portrait images from the no as-

sistance set and the audio-guided set were analyzed.

There was no significant statistical difference such as

the average of all participants, but the following ten-

dency was seen. Also at this point it was suggested

that there are two attributes as follows.

The experimental result indicates that audio guide

did affect the viewing time and the frequency of fixa-

tions. Most of the participants, as it can be observed

for participants 6 and 9, tended to evaluate their con-

tentment low when there is no assistance. On the

other hand, contentment evaluation tended to be high

when there is an audio-guide assistance. However,

there were some participants, as it can be observed

for participants 1 and 17, who evaluated contentment

to be high although there is no assistance and stated

even higher contentment evaluation for audio guide.

Therefore, the results of participants 6, 9, 1, and 17

were examined.

Audio-guide changed not only the contentment

evaluation but also how the participants perceived the

images, because audio-guide provided the informa-

tion regarding images and the images’ point of inter-

est. Figures 4 to 6 graphically illustrate the change of

contentment. As shown in Figures 5 and 6, all par-

ticipants could not feel Cerebral Happiness without

audio guide, but they could feel it with audio guide.

In the viewing time aspect, audio-guide assistant

increased most participants’ viewing time greatly ex-

ceeding the length of the audio-guide assistant, which

was about 65 seconds as shown in the Figure 7. Con-

versely, there were some participants such as partici-

pant 1 and participant 17 whose viewing time didn’t

change significantly. The experiment result indicates

that the change in the viewing time tended to conform

with the contentment evaluation.

For eye movements, most participants with audio-

guided assistant tended to look at a certain location

following the audio-guide resulting in reducing fre-

quency of fixations. However, the frequency of fixa-

tions of some participants such as participant 17 in-

creased instead. According to the interview, partici-

pant 17 stated that he was distracted by audio-guide.

Moreover, he stated that he would like to have in ex-

planation text instead of audio-guide. Figure 8 graph-

ically illustrates the change of eye movements.

Figure 4: Effect on contentment.

Figure 5: Effect on acquisition of knowledge.

4.3 Audio Guide and Viewing

Time/Frequency of Fixations

In this part, all images were analyzed. To analyze

the effect of contentment and audio-guide, a viewing

time - frequency of fixations plot is created as shown

in the Figures 9 to 11. Figure 9 does not show any

obvious result. However, when the data between non-

assisted and audio-guided assistant are separated, a

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

22

Table 4: Correlations between evaluations and eye movements in non-guided portrait.

Happiness Amusement Contentment Q-7

Viewing Time [sec] 0.508

∗

0.111 0.270 0.394

Frequency of Fixation [counts/sec] -0.502

∗

-0.466

∗

-0.571

∗

-0.485

∗

∗

p < .05

Q-7: “That study has activated new knowledge.”

Figure 6: Effect on acquisition of point of interest.

Figure 7: Effect on viewing time.

Figure 8: Effect on frequency of fixations.

Figure 9: Time - frequency of fixations plot.

clear trend can be seen in Figure 10 and Figure 11. In

non-assisted condition, the viewing time and the fre-

quency of fixations did not have any clear interaction.

On the other hand, these plots concentrated within the

certain area for audio-guided condition.

Figure 10: Time - frequency of fixations plot: non-guided.

Figure 11: Time - frequency of fixations plot: audio-guided.

4.4 Cluster Analysis

By using participants’ contentment evaluation, a table

of participants’ contentment acquisition was obtained

as shown in the Table 5. This table was further ana-

lyzed with quantification method no.III in order to see

any trend in participants. In the result, the way of

each acquisition of contentment was described in two

dimensions: the first axis was “abstract painting – fig-

urative painting.”, and the second axis was “guide is

necessary – guide is unnecessary”. With the score re-

sulted from quantification method no.III, participants

can be classified and grouped into four types as shown

in Figure 12 using the Ward method. Although partic-

ipant 16 was classified in Group C with the score, this

Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience - Relationships between Visitorsâ

˘

A

´

Z Eye Movements, Audio Guide

Contents, and the Levels of Contentment

23

participant had a different way to feel contentment.

It was supposed that participant 16 might be a par-

ticipant who doesn’t feel contentment with paintings.

Therefore, the score of participant 16 was not plotted.

Figure 12: Contentment acquision.

5 DISCUSSION

5.1 Audio Guide

According to the interview, participants who per-

ceived positive emotion evaluated their contentment

high. This occurred because contentment is also a

positive emotion, and it might be difficult to differ-

entiate the positive emotions in the individual. The

participants who evaluated high contentment tended

to think about background of paintings, which would

result in an increase in viewing time and a decrease

in frequency of fixations. On the other hand, partici-

pants who perceive negative emotions while viewing

a particular image didn’t think about background of

paintings.

However, as presented in Section 4.2, novices,

who couldn’t have any ideas without guide, got idea

and felt contentment with audio guide. Audio guide

led participants to watch the explained point without

hesitation and the frequency of fixations tends to de-

crease.

Still, there are also novices think the audio guide

is annoying such as participant 17. Most of novices

can enjoy paintings with any information because

of their ignorance about paintings. But the novices

who needed specific information at that time think

the audio guide is annoying and want the explanation

text instead when audio guide lead them into another

point. Difference between point of interest and audio

guide might increase the frequency of fixations.

The concentrated phenomena presented in Section

4.3 is caused by audio-guided since it leads partici-

pants to look at the point of interest in the same se-

quence. In fact, the impressions of paintings with au-

dio guide was the same for most of the participants.

5.2 Analysis of the Need of Particular

Participant

The characteristics of the cluster classified in Section

4.4 were considered in this section.

• Group A

They can’t understand abstract without audio

guide, but they could enjoy in their way(e.g.

brushwork, colors).

• Group B

They are classified as typical museum novices: it

is difficult for them to have their own ideas. Al-

though it is possible to feel contentment with au-

dio guide, they want explanations of overt ele-

ments for audio guide instead of the information

of artist.

• Group C

They can enjoy paintings with audio guide, and

also enjoy portrait and landscape which are easy

to understand without audio guide.

• Group D

They can feel contentment without audio guide.

When the contents of audio guide is not they want

to know or from the time constraints, audio guide

annoys them.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORKS

This paper studies the effect of audio guide on the

levels of contentment of museum novices by analyz-

ing the patterns of eye movements while appreciat-

ing objects with or without audio guide. For that

we have done eye tracking experiments and show the

effects of audio guide and possibility of using eye

movements to estimate novice’s contentment. Con-

tentment can be used to differentiate each person’s

image perception. This information can be used to

decide what kind of support a particular person needs

and enhances novices’ experience. Still, we could not

get much statistically significant results, so it is im-

portant to improve the method in the future.

In this paper, we supported that providing an audio

guide without additional displays such as text guide,

which have been used widely in museums. Moreover,

other assistances, e.g., text guide and video guide,

should be considered in the future. Understanding the

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

24

Table 5: Contentment acquisition of each subject.

Participant Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

Portrait X X X X X

Landscape X X X X X X X X X X X X

Abstract X X X

Portrait (Audio) X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

Landscape (Audio) X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

Abstract (Audio) X X X X X X X X X X X

X: contentment, blank: not contentment

effectiveness of assistance for novices can be also ex-

tended after considering the length and timing of as-

sistance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant

Number 15H02784.

REFERENCES

Evans, J. S. B. (2003). In two minds: dual-process ac-

counts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences,

7(10):454–459.

Evans, J. S. B. T. (2010). Thinking Twice: Two Minds in

One Brain. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Evans, J. S. B. T. and Frankish, K., editors (2009). In Two

Minds: Dual Processes and Beyond. Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford.

Gross, J. J. and Levenson, R. W. (1995). Emotion elicitation

using films. Cognition & Emotion, 9(1):87–108.

Jacob, R. and Karn, K. S. (2003). Eye tracking in human-

computer interaction and usability research: Ready to

deliver the promises. Mind, 2(3):4.

Kahneman, D. (2003). A perspective on judgment and

choice. American Psychologist, 58(9):697–720.

Kintsch, W. (1988). The use of knowledge in discourse pro-

cessing: A construction-integration model. Psycho-

logical Review, 95:163–182.

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cog-

nition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Kitajima, M. (2016). Memory and Action Selection in

Human-Machine Interaction. Wiley-ISTE, 1 edition.

Kitajima, M., Akamatsu, M., Maruyama, Y., Kuroda, K.,

Katou, K., Kitazaki, S., Minowa, Y., Inagaki, K., and

Kajikawa, T. (2009). Information for Helping Drivers

Achieve Safe and Enjoyable Driving: An On-Road

Observational Study. In Proceedings of the Human

Factors and Ergonomics Society 53rd Annual Meeting

2009, pages 1801–1805, Santa Monica, CA. Human

Factors and Ergonomics Society.

Kitajima, M. and Toyota, M. (2013). Decision-making and

action selection in Two Minds: An analysis based on

Model Human Processor with Realtime Constraints

(MHP/RT). Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architec-

tures, 5:82–93.

Morris, D. (2006). The nature of happiness. Little Books

Ltd., London.

Okumoto, M. and Kato, H. (2010). The cognitive orien-

tation of museum (com) model for museum novices.

Educational Technology Research, 33(1):131–140.

Solso, R. L. (1996). Cognition and the Visual Arts. MIT

press.

Tullis, J. G. and Benjamin, A. S. (2011). On the effective-

ness of self-paced learning. Journal of Memory and

Language, 64(2):109 – 118.

Yarbus, A. L. (1967a). Eye Movements and Vision. Plenum,

New York.

Yarbus, A. L. (1967b). Eye movements during perception of

complex objects, pages 171–211. Plenum, New York.

APPENDIX

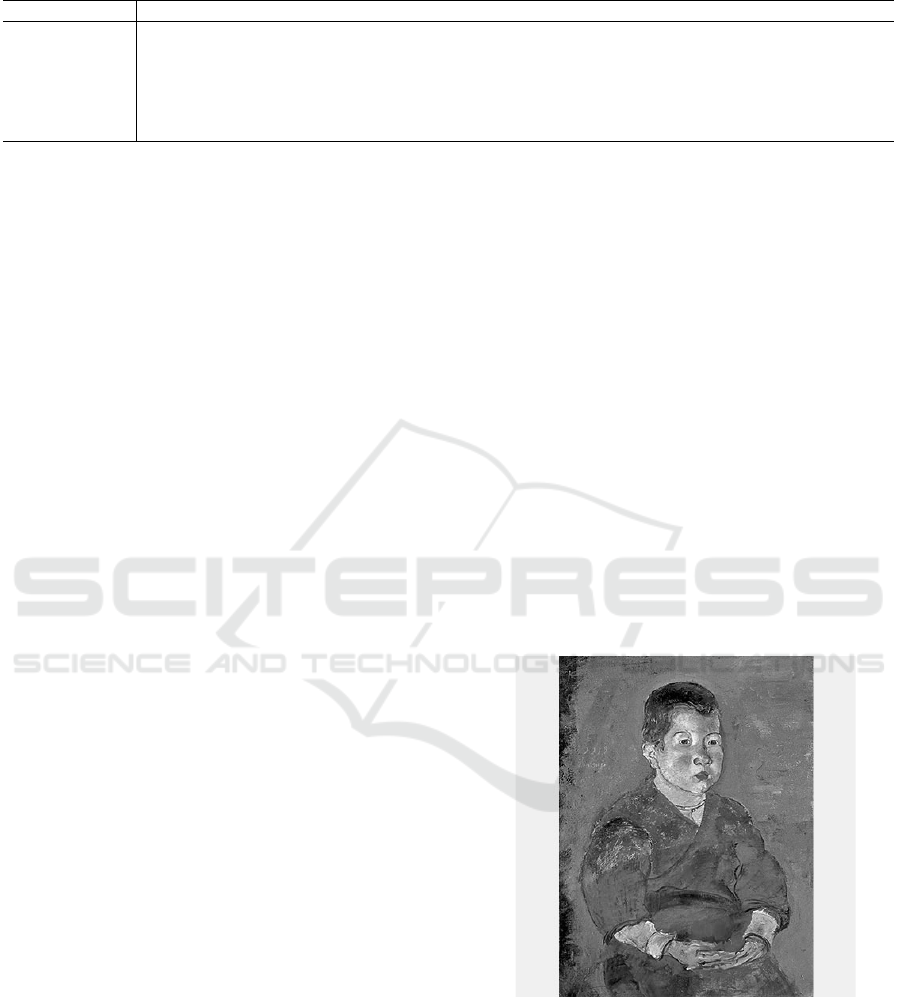

Figure 13: Sekine Shoji, Boy, 1919, ID: P.

Utilization of Audio Guide for Enhancing Museum Experience - Relationships between Visitorsâ

˘

A

´

Z Eye Movements, Audio Guide

Contents, and the Levels of Contentment

25

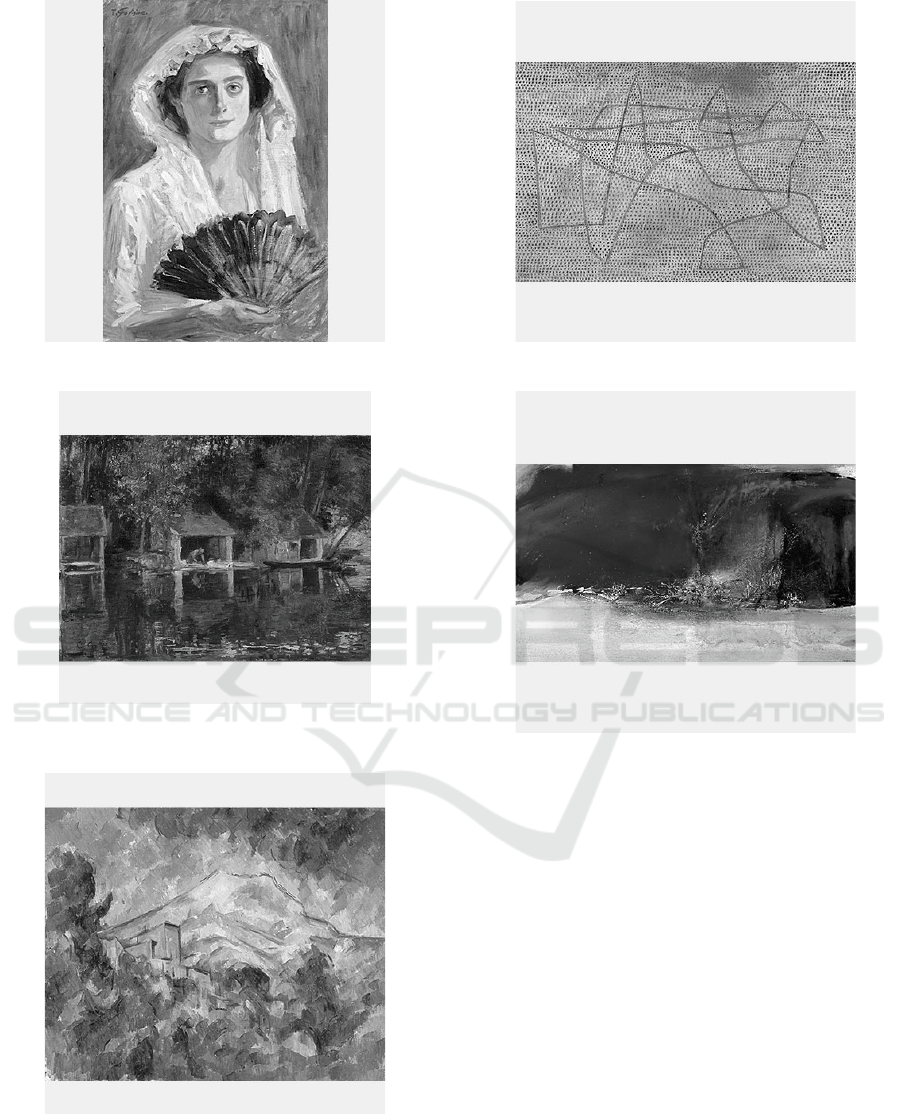

Figure 14: Fujishima Takeji, Black Fan, 1908-09, ID: Pa.

Figure 15: Asai Chu, Laundry Place at Grez-sur-Loing,

1901, ID: L.

Figure 16: Paul Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire and

Chateau Noir, 1904-06, ID: La.

Figure 17: Paul Klee, Island, 1932, ID: A.

Figure 18: Zao Wou-Ki, 07.06.85, 1985, ID: Aa.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

26