Improving Student Content Retention using a Classroom Response

System

Robert Collier

1

and Jalal Kawash

2

1

Department of Computer Science, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Dr., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

2

Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary, 2500 University Dr. NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Keywords:

Classroom Response System, Content Retention, Student Engagement, Computer Literacy.

Abstract:

The most typical uses of a classroom response system are to improve student engagement and to provide op-

portunities for immediate feedback. For our introductory course in computer science we sought to investigate

whether the content and format typically associated with a classroom response system could be adapted from

a feedback tool into an approach for improving content retention. We devised an experiment wherein differ-

ent sections would be presented with complementary sets of questions presented either immediately after the

corresponding material (i.e., for feedback) or at the beginning of the following lecture, with the express pur-

pose of reminding and reinforcing material (i.e., to improve content retention). In every case, the participants

that encountered an item in the following lecture exhibited relatively better performance on the corresponding

items of the final exam. Thus our evidence supports the hypothesis that, with no significant additional invest-

ment of preparation or lecture time (beyond that associated with all classroom response systems), questions

can be presented in such a way as to engage students while simultaneously improving content retention.

1 INTRODUCTION

Classroom response systems (and particularly those

that require only the ubiquitous smart phone with

which to interact) present an excellent opportunity for

instructors to integrate technology into the classroom

in a way that helps facilitate student learning. These

systems, exemplified by the practice of posing a ques-

tion to the class that is answered immediately and

anonymously, are known to improve student engage-

ment. Furthermore, these systems offer an opportu-

nity for both students and instructors to receive cru-

cial and immediate feedback about the effectiveness

of a lecture.

These express purposes notwithstanding, in this

paper we explore the results of an investigation into

whether or not classroom response systems can also

provide an opportunity for improving content reten-

tion through an active (albeit brief) return to previ-

ously discussed content, without sacrificing its use as

a tool for assessment and improving student engage-

ment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as fol-

lows. Section 2 discusses related work in the context

of the use of classroom response systems. The course

in which our experiment takes place is discussed in

Section 3. The experiment design is presented in Sec-

tion 4, and the results are given in sections 5 and 6.

Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 7.

2 CLASSROOM RESPONSE

SYSTEM

The feedback provided by a classroom response sys-

tem can be crucial to both students and instructors. A

question on which a particular student under-performs

(with respect to the other students in the class) can

indicate an area of weakness, and in this way a stu-

dent’s relative performance becomes a discrete oppor-

tunity for that student to self-assess his or her cur-

rent understanding. Furthermore, the immediate and

specific nature of the feedback provided by a class-

room response system can be contrasted against tra-

ditional assessment tools (e.g., quizzes, assignments,

etc.) where several topics are often assessed simul-

taneously and feedback is not immediately available.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, the feed-

back provided to instructors allows instructors to ad-

just the pace of the lecture to match the immediate

learning needs of the participating students.

Collier, R. and Kawash, J.

Improving Student Content Retention using a Classroom Response System.

DOI: 10.5220/0006218100170024

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 1, pages 17-24

ISBN: 978-989-758-239-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

17

Numerous studies ((Boscardin and Penuel, 2012;

Moss and Crowley, 2011; Kay and LeSage, 2009;

Bruff, 2009; Moredich and Moore, 2007)) have re-

ported that the use of classroom response systems in

the classroom can improve student engagement (to

the benefit of student learning) and (as noted previ-

ously) provide an opportunity for both students and

instructors to receive important feedback. Although

virtually all surveyed materials reinforce that students

are satisfied, on more than one occasion ((Blasco-

Arcas et al., 2013; Webb and Carnaghan, 2006)) it

has been noted that the studies that report learning

improvements might be observing an effect associ-

ated with improved interactivity in the classroom, and

cannot conclusively demonstrate that the classroom

response system is actually required to achieve this

effect. This reasonable consideration notwithstand-

ing, the use of classroom response system as a tool to

engage students remains largely undisputed. Class-

room response systems have also been used to suc-

cessfully identify students that are struggling (Liao

et al., 2016), and Porter et al. showed that perfor-

mance in classroom response system early in the term

was a good predictor of students’ outcomes at the end

of the term (Porter et al., 2014).

Unfortunately it must also be acknowledged that

there is evidence that the adoption of a classroom

response system could present a barrier to students

(which could, naturally, negatively interfere with

knowledge retention). Draper and Brown (2004) re-

ported that some students expressed that the system

could actually be a distraction from the learning out-

come. Furthermore the review by Kay and Lesage

(2009) cited works that discussed the potential for in-

class discussions to actually confuse students by ex-

posing students to differing approaches/perspectives.

This is, naturally, a potential pitfall for any activity

that prompts in-class discussion, and given the nu-

merous reports of the potential advantages associated

with classroom response systems, we definitely feel

that there is sufficient evidence to motivate the inves-

tigation of these systems as a tool for improving con-

tent retention.

It should be noted that a number of reviews

(Boscardin and Penuel, 2012; Kay and LeSage, 2009;

Judson and Sawada, 2002) have noted that much of

the research into the benefits and drawbacks associ-

ated with the use of classroom response systems has

been qualitative and/or anecdotal, and that there are

relatively few studies using control groups and quan-

titative analyses. The authors believe this study to be

among the first to offer a quantitative assessment of

the use of classroom responses systems as a tool to

improve content retention (as opposed to a tool ex-

plicitly used for improving engagement or providing

student feedback). It should, however, be specifically

noted that the approach described by Brewer (2004)

in the biology faculty at the University of Montana

noted that although response system questions were

presented to students during the class in which the

materials were presented, correct answers would not

be revealed to the students until the following class.

Although this practice could conceivably improve re-

tention as well, the express purpose of using the re-

sponse system was described in that study to be feed-

back (for both the instructors and students), not an

improvement to retention. Similarly, Caldwell (2007)

does not mention retention specifically but does de-

scribe a ”review at the end of a lecture” - this could

also conceivably improve retention if these questions

pertained to the beginning of a particularly lengthy

lecture.

It should also be emphasized that our paper is con-

cerned only with the potential applications of class-

room response systems to the problem of content re-

tention; although several other studies have looked

at classroom response systems for the retention of

students in computer science programs, this is not

directly related to the problem of content retention.

Porter, Simon, Kinnunen, and Zazkis (2013 & 2010),

for instance, indicated that they used clickers as one

of the best practices for student retention, but it is not

clear how this class response system is used and how

it is affecting content or knowledge retention. Fur-

thermore, unlike Tew and Dorn (2013), we do not aim

to develop general instruments for assessment. Our

approach is ad-hoc with the specific objective of de-

termining if there is measurable evidence that a class

response system can help improve retention of con-

tent and knowledge by students.

A related issue for which there have been sev-

eral studies (albeit with conflicting results) concerns

whether or not the use of classroom response sys-

tems can improve student performances on final ex-

ams. Diana Cukierman suggested that studying the

effect of a classroom response system on outcomes

such as final exam scores may be infeasible (Cukier-

man, 2015) and an experiment by Robert Vinaja that

used recorded lectures, videos, electronic material,

and a classroom response system did not demonstrate

an impact of these practices on grade performance

(Vinaja, 2014). Contrarily, Simon et al. demonstrated

in a CS0 course that peer instructed subjects outper-

formed those who are traditionally instructed (Simon

et al., 2013), and Daniel Zingaro confirmed this find-

ing but in a CS1 context (Zingaro, 2014). Zingaro

et al. went further to show that students who learn

in class retain the learned knowledge better than stu-

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

18

dents who did not learn in class (Zingaro and Porter,

2015). Steven Huss-Lederman similarly reported on a

2-year experiment in which first year students showed

better learning gains as a result of using a classroom

response system, but there was a drop in these gains in

the second year (Huss-Lederman, 2016). In compari-

son, our work starts from the thesis that classroom re-

sponse system possibly have an effect on knowledge

retention (and, by extension, on final exam scores).

Our aim was to quantify this observation in a first-

year computer science course and in contrast with

the aforementioned studies, the driving question of

our research is when and how classroom response

questions can be effective in improving learning out-

comes. Specifically, we compared two groups which

both used the same classroom response system and

similar question banks - it was the only the order in

which these questions were delivered that differed.

3 COURSE DETAILS AND

OBJECTIVES

The course within which this experiment was con-

ducted was CPSC203, Introduction to Problem Solv-

ing Using Application Software.) This was a first

year computer literacy course at the University of Cal-

gary designed specifically for students not working

towards a major in computer science. Consequently,

this course did not assume students have any founda-

tion of computer science knowledge upon which to

build (although a basic level of familiarity with the

use of a personal computer was assumed). Most of

the students in attendance are undergraduate students

enrolled in a course from the schools of business,

management, and/or social science, but students from

the natural sciences, communications, and other dis-

ciplines also register for this course on a regular basis.

The course is taught in a traditional lecture-style for-

mat, with content delivered over 13 weeks through a

combination of lectures (75 minutes, twice a week)

and tutorials (100 minutes weekly).

As the principle learning outcome for this course

is to impart an introduction to many of the fundamen-

tal areas of the computer science discipline, the course

features a particularly broad range of topics. After the

initial weeks of the course, during which some very

basic introductory materials are presented alongside

a discussion of research design fundamentals, the re-

mainder of the course could be logically divided into

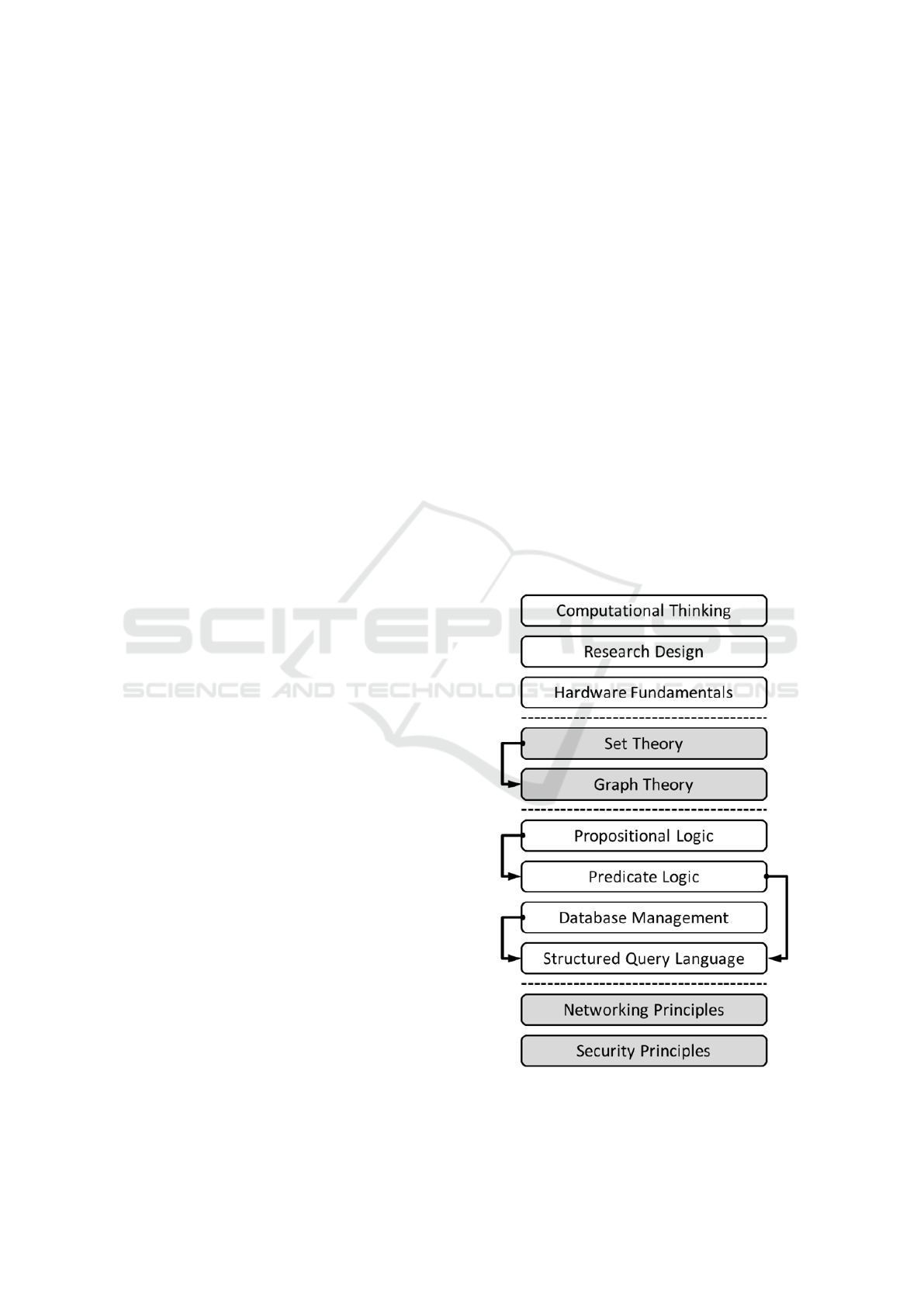

three“modules”. Figure 1 is a diagrammatic represen-

tation of the topics of the course, presented to students

during the first (i.e., introductory) lecture to demon-

strate the interconnectedness and dependencies of the

topics to follow. The arrows indicate topic depen-

dence.

The first of these modules introduces both set the-

ory and graph theory before discussing the applica-

tion of these principles to problem-solving (e.g. traf-

fic light scheduling). During some previous offerings

of this course these topics are followed by several

short introductory computer programming lectures,

but these lectures were not presented as part of the

course offerings discussed in this paper.

The module that follows introduces both proposi-

tional and predicate logic before exploring the funda-

mentals of relational database management systems.

These topics (i.e., classical logic and database man-

agement) are then brought together for the introduc-

tion of structured query language.

The final module provides a brief introduction to

the principles of computer networking and security

(e.g., encryption and authentication with public-key

cryptography. Although these topics are somewhat in-

dependent of the previous materials, they do broaden

the knowledge base to ensure that students are able

to remember, understand, and apply many core com-

puter science topics.

Figure 1: Topics and Dependencies.

Improving Student Content Retention using a Classroom Response System

19

4 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

At the time of this investigation, the use of a class-

room response system in CPSC203 has been standard

operating procedure since 2010. Although these sys-

tems are widely recognized to encourage student en-

gagement while allowing instructors to assess the de-

gree to which the current material is being absorbed,

it might be possible to improve the benefit to the stu-

dents by using these systems to revisit and reinforce

content discussed in a prior lecture. Notwithstanding

the fact that it is necessary to ask students about the

content that has been presented over the last few min-

utes to determine if they have absorbed the material

and/or created adequate study notes, asking questions

pertaining to content that is still fresh in the minds of

the students (i.e., in either working or intermediate-

term memory) might do very little to aid students in

storing the material into long-term memory.

The fall semester of 2014 afforded a unique op-

portunity for a controlled experiment on the effec-

tiveness of the Tophat classroom response system for

improving content retention; the two sections were

taught by the same instructor, in (nearly) synchronous

75-minute lectures, with shared assignments, quizzes,

and examinations. The two weekly lectures for each

section were also taught on the same days (Tuesdays

and Thursdays) with the most significant observable

differences (at the time the experiment was designed)

being that one section would receive its lectures start-

ing at 9:30 AM and would contain roughly half as

many students as the other, which would receive its

lectures starting at 12:30 PM. From this point these

two sections will be referred to as the early section

(or the early group) and the late section (or the late

group), respectively.

The performance discrepancy that might be at-

tributed to the differing lecture times notwithstanding,

a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine if

there were any statistically significant differences be-

tween the scores on the portion of the final exam per-

taining to this investigation. This nonparametric test,

applied to the final exam scores of the 26 participants

that made up the sample from the early section and

the 46 participants that made up the sample from the

late section, did not indicate a statistically significant

difference in their respective final exam performances

(D-value of 0.1378 and p-value of 0.898).

For this experiment, a collection of 54 questions

was developed for the period of 14 lectures during

which the Tophat classroom response system would

be in use. Additionally, a minor variation on each

of these 54 questions was also developed to ensure

that the late section would never receive an identi-

cal question to one that had already been asked of the

early section. The course was designed such that four

questions would be posed to each section during each

lecture (except during the first lecture, which would

feature only two). The four questions associated with

each lecture would be divided (at random) into com-

plementary sets A and B (of two questions each) - the

early sample would be asked the questions from set A

immediately after the material was presented and the

questions from set B at the beginning of the follow-

ing class, while the late section would be assigned the

reverse.

As a clarifying example, if the four questions as-

sociated with the nth lecture of the course were des-

ignated q1, q2, q3, and q4, the early section could be

asked questions q2 and q3, immediately after the ma-

terial had been presented, and questions q1 and q4 at

the beginning of the n+1

th

lecture. The late section,

on the other hand, would be asked variations on ques-

tions q1 and q4 immediately after the material had

been presented and questions q2 and q3 at the begin-

ning of the n+1

th

lecture.

In this way, both classes answered 27 questions

immediately after the material was presented (allow-

ing for the traditional role of the classroom response

system as an engagement/assessment tool) and 27

questions on the following class (wherein the class-

room response system questions become an opportu-

nity for students to revisit the material that had been

presented during a previous lecture).

5 “MULTIPLE CHOICE” ITEM

RESULTS

For the early group, within which there were 26 par-

ticipants, the average participation level was 73.18%

(standard deviation 27.16; with 0% and 100% indicat-

ing participants that did not answer any of the class

response system questions and answered every ques-

tion, respectively). For the late group, within which

there were 46 participants, the average participation

level was 72.48% (standard deviation 24.85). As

there was a substantial difference between the num-

ber of students in each group and a lack of normality

in the data, the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test was used to determine if there were any statisti-

cally significant differences between the correspond-

ing participation levels. With a calculated D-value

(for the maximum difference between the distribu-

tions) of 0.1288 and a very large p-value of 0.929,

the null hypothesis (that both samples come from a

population with the same distribution) cannot be re-

jected. It is, thus, not unreasonable to conclude that

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

20

both groups were equally willing to participate (or,

more precisely, the difference in participation levels

was not considered statistically significant).

A simple performance assessment (with respect to

the classroom response system questions only) can

be derived for each participant as the fraction of the

questions answered by the participant that were, in

fact, answered correctly. In the early group the av-

erage performance was 70.66% (standard deviation

13.74) while in the late group the average perfor-

mance was 66.95% (standard deviation 13.54). Once

again the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to de-

termine if there were any statistically significant dif-

ferences (since the data sets were not normally dis-

tributed) but with a D-value of 0.2533 and a p-value

of 0.218, the null hypothesis that both samples came

from the same distribution cannot be rejected. It is

not unreasonable to interpret, from this, that neither

of the participant groups was able to outperform the

other. This is a welcome result considering that both

groups received exactly the same number of questions

for both the engagement and retention questions.

Having established that it would not be unreason-

able to compare each of the groups on specific ques-

tions (to assess the degree to which specific ques-

tions can improve retention), four of the twenty mul-

tiple choice questions and one of the eight short an-

swer questions from the final exams were designed

such that they would both reflect and resemble class-

room response system questions encountered by the

class. Although this is unarguably a rather small sam-

ple from which to draw conclusions, it is important

to recognize that the typical classroom response sys-

tem question (i.e., designed to improve student en-

gagement and provide an opportunity for feedback)

is not necessarily a suitable question for a summative

assessment tool like a final exam.

It should be noted that virtually all of the ma-

terial from the final exam was accompanied by at

least one related classroom response system question

(with the exception of one multiple choice question

and one short answer question that addressed mate-

rial covered in the first three weeks, before the class-

room response system came into use). Nevertheless

it must also be noted that most of the corresponding

final exam questions did not resemble their classroom

response system counterparts. Consequently the au-

thors feel that the most generalizable conclusions will

be drawn from the observed performance differences

(between students that encountered the corresponding

classroom response question during the same lecture

as the material vs. the following lecture) for those

exam questions where the parallels to the correspond-

ing classroom response questions were undeniable.

Two of the four multiple choice final exam ques-

tions pertained directly to structured query language

(SQL). The former (denoted MCQ1) requested that

the students select the correct “where” clause to

produce a specific result, while the latter (denoted

MCQ2) presented a SQL query and requested the

students provide the number of rows that would be

returned. Of the group of students that encoun-

tered MCQ1 during the same lecture as the corre-

sponding material (i.e., the lecture on the construc-

tion of “Where” clauses), 38.5% answered the class-

room response system question correctly and 57.7%

answered the corresponding final exam question cor-

rectly. If this is contrasted against the group of stu-

dents that encountered MCQ1 during the following

lecture (i.e., at least 48 hours later), only 32.6% an-

swered the classroom response system question cor-

rectly but 60.9% answered the final exam question

correctly. A simple summary of these results would

observe that the group of students that received the

classroom response system question in the following

lecture did “better” on the final exam question, even

though their performance on the classroom response

question was worse than the other group. This result

is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Performance on an application level question.

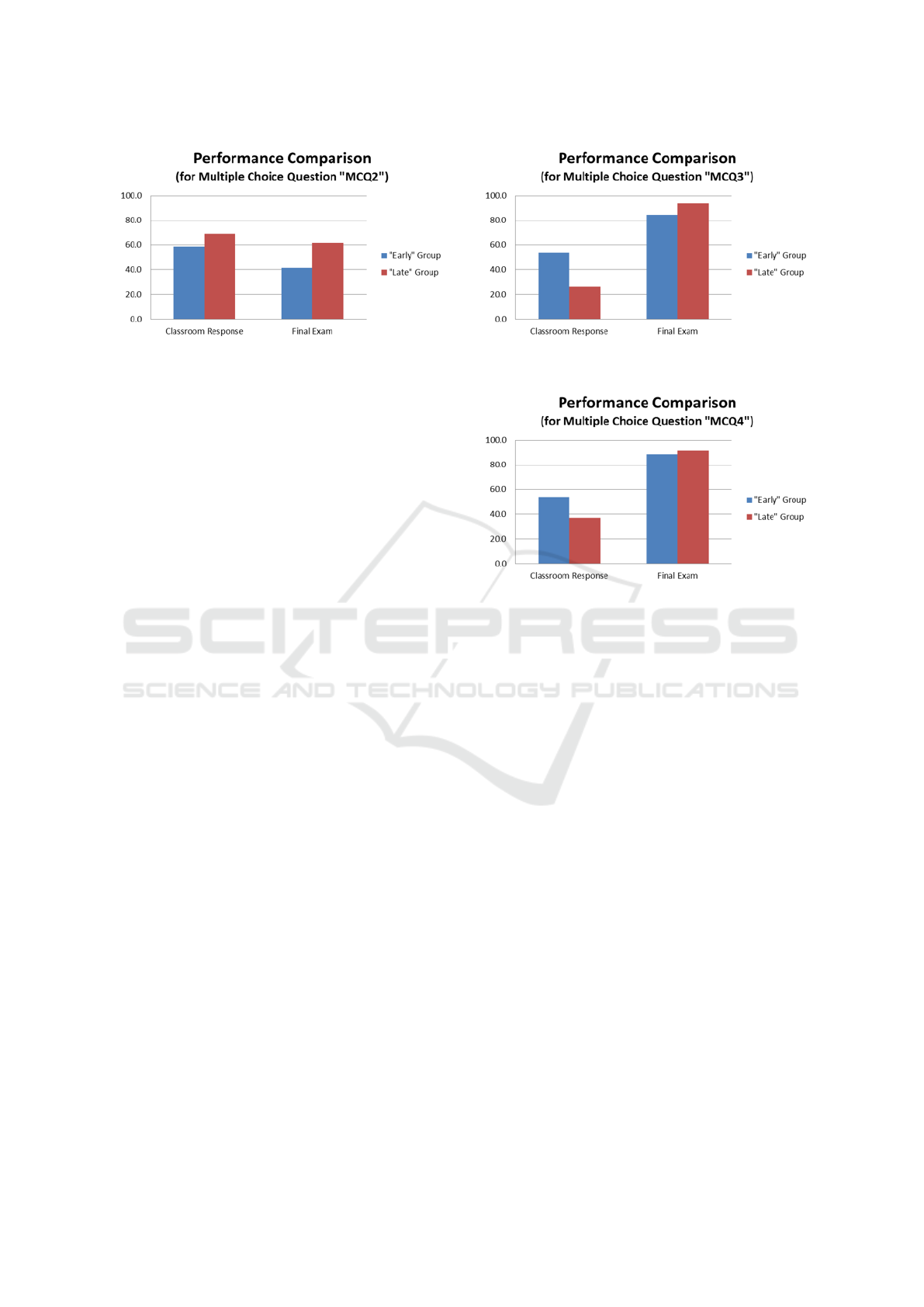

Of the group of students that encountered MCQ2

during the same lecture as the corresponding material

(i.e., the lecture on Cartesian products and join oper-

ations), 58.7% answered the classroom response sys-

tem question correctly and 41.3% answered the corre-

sponding final exam question correctly. Of the other

group, on the other hand, 69.2% answered the class-

room response system question correctly and 61.5%

answered the final exam question correctly. As with

MCQ1, the students that received the classroom re-

sponse system question in the following lecture did

“better” on the final exam. It may, however, be worth

noting that this same group performed “better” on the

classroom response system question as well. This re-

sult is depicted in Figure 3.

Improving Student Content Retention using a Classroom Response System

21

Figure 3: Performance on an application level question.

The other two of the four multiple choice final

exam questions considered for this investigation per-

tained to networking. Using the terminology from

the cognitive domain of Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom,

1956), where the structured query language questions

discussed previously could be said to assess at the ap-

plication level, these networking questions would be

best categorized as assessment tools for the knowl-

edge and comprehension levels (respectively). The

former (denoted MCQ3) pertained to the differences

between user datagram protocol (UDP) and trans-

mission control protocol (TCP) and the latter (de-

noted MCQ4) pertained to the POST and GET oper-

ations of the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). Of

the group of students that encountered MCQ3 dur-

ing the same lecture as the corresponding material,

53.8% answered the classroom response system ques-

tion correctly and 84.6% answered the correspond-

ing final exam question correctly. For the sample

that encountered the classroom response question dur-

ing the following lecture, 26.1% answered the class-

room response system question correctly and 93.5%

answered the corresponding final exam question cor-

rectly. In spite of the very significant difference in

performance on the classroom response question it-

self (with only 26.1% of the late sample answered the

classroom response question correctly), once again

the final exam question results indicate that the group

of students that received the classroom response sys-

tem question in the following lecture did “better” on

the final exam. This result is depicted in Figure 4.

Of the group of students that encountered MCQ4

during the same lecture as the corresponding material,

53.8% answered the classroom response system ques-

tion correctly and 88.5% answered the corresponding

final exam question correctly. When this is contrasted

against the results from the late group, the familiar

pattern was evident; 37.0% of the late group answered

the classroom response question correctly but 91.3%

answered the final exam question correctly. This re-

sult is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Performance on an application level question.

Figure 5: Performance on an application level question.

It is worthy to note at this point that these re-

sults are very intuitive; a classroom response question

posed to the class at the beginning of the lecture, but

pertaining to content from a previous lecture, is not

being used to provide feedback about the immediate

learning needs of the classroom. It does, however,

stand to reason that such a question is an opportunity

to reinforce (and bridge the current lecture with) con-

tent from a previous lecture, thereby improving stu-

dent retention. This would, naturally, be evidenced

by a relative performance improvement on the corre-

sponding questions of the final exam

6 “SHORT ANSWER” ITEM

RESULTS

The final question posed to the students on the final

exam that corresponded directly to a classroom re-

sponse question previously encountered by the stu-

dents used the short answer format (i.e., it was neither

a multiple-choice question nor was it any other format

where prompts or possible answers were provided to

the student). This question entailed the creation of a

graph that, when subjected to a graph colouring al-

gorithm (n.b., one of the earlier topics on the course)

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

22

requires the same number of colours as the number of

vertices in the graph. Consequently it could be argued

that according to the terminology from the cognitive

domain of Bloom’s taxonomy this question was a syn-

thesis level question.

Figure 6: Performance on a synthesis level question.

Both the early and late participate samples (i.e.,

those that encountered the classroom response ques-

tion immediately after the material was presented in

lecture or at the beginning of the following lecture, re-

spectively) achieved the same performance level (i.e.,

50%) on the classroom response question. Neverthe-

less, the results of the experimental analysis indicated

that the average mark achieved (on the corresponding

short answer question of the final exam) by the late

sample was greater than the average mark achieved

by the early sample (78.0% and 73.3%, respectively).

Although this is consistent with the previous results,

the conclusion must be tempered by the fact that this

difference was not found to be statistically significant

(according to an unpaired student t-test). The distri-

butions of students (from the early and late samples)

that achieved full marks, partial marks, or no marks

on the corresponding final exam question is depicted

in Figure 6.

7 CONCLUSIONS

As any educator that has employed a classroom re-

sponse system can attest, the creation of suitable items

is a considerable investment of time - both the time

required to develop a suitable item and the time con-

sumed in class to present the item, allow the students

to formulate and submit a response, and discuss the

results. That said, there are well-established benefits

to the class if these costs can be incurred, most no-

tably as an approach for improving student engage-

ment and (if the questions are a source of marks

for the student) motivate, and as source of immedi-

ate feedback for both the students and the instruc-

tors. The results of this experiment support the hy-

pothesis that the very same activity can also be used

to improve student retention simply by varying when

these questions are presented to the student. Ques-

tions posed to the students at the beginning of the lec-

ture that follows the lecture where the corresponding

materials were introduced are an opportunity for stu-

dents and instructors to briefly revisit material in a

structured activity, and this, in turn, presents an op-

portunity for students to reinforce knowledge that has

passed into long-term memory. It is also worth not-

ing that although this approach does entailing sacri-

ficing the utility of the classroom response question

as an approach for acquiring immediate feedback, it

does not preclude the other more typical application

of these questions as a way of motivating or engaging

students.

The five items from the final exam (i.e., the four

multiple choice questions and one short answer ques-

tion) used for this experiment were designed such that

they would assess (as much as possible) knowledge at

several different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy while at

the same time having a clear and apparent connection

to a previously encountered item. Every student in at-

tendance of the lecture (regardless of whether or not

they participated in that specific classroom response

activity) would have encountered the question (and

subsequent discussion), with the only difference be-

ing when they encountered it. In all cases, the student

sample that encountered the classroom response item

in the following lecture exhibited better performance

than the student sample that encountered the item im-

mediately after the material had been presented. As

noted previously, this is an intuitive and not particu-

larly surprising result, since the item was obviously

Improving Student Content Retention using a Classroom Response System

23

not being used to generate immediate feedback if it

did not accompany the corresponding lecture content.

Contrarily, these items, though structurally identical

to a traditional classroom response question, were

used to improve retention rather than generate feed-

back. It is encouraging that the use of these retention

questions would appear to be correlated with measur-

able improvements in performance.

It is, however, noteworthy that the results would

also seem to suggest (albeit with less certainty) that

students do not perform as well on these questions

when delivered in the following lecture. This is also a

relatively intuitive result, but the impact was measur-

able and should be considered if classroom response

activities are used in part to determine a student’s fi-

nal grade. This makes intuitive sense since students

may learn more from early mistakes or failure than

they would when they get it right while not fully un-

derstanding it.

REFERENCES

Blasco-Arcas, L., Buil, I., Hernandez-Ortega, B., and Sese,

F. J. (2013). Using clickers in class. the role of in-

teractivity, active collaborative learning and engage-

ment in learning performance. Computers & Educa-

tion, 62:102–110.

Boscardin, C. and Penuel, W. (2012). Exploring benefits of

audience-response systems on learning: a review of

the literature. Academic Psychiatry, 36(5):401–407.

Bruff, D. (2009). Teaching with Classroom Response

Systems: Creating Active Learning Environments.

Jossey-Bass.

Cukierman, D. (2015). Predicting success in university first

year computing science courses: The role of student

participation in reflective learning activities and in i-

clicker activities. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM

Conference on Innovation and Technology in Com-

puter Science Education, ITiCSE ’15, pages 248–253,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Huss-Lederman, S. (2016). The impact on student learning

and satisfaction when a cs2 course became interactive

(abstract only). In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Tech-

nical Symposium on Computing Science Education,

SIGCSE ’16, pages 687–687, New York, NY, USA.

ACM.

Judson, E. and Sawada, D. (2002). Learning from past and

present: Electronic response systems in college lec-

ture halls. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and

Science Teaching, 21(2):167–181.

Kay, R. H. and LeSage, A. (2009). Examining the benefits

and challenges of using audience response systems:

A review of the literature. Computers & Education,

53(3):819–827.

Liao, S. N., Zingaro, D., Laurenzano, M. A., Griswold,

W. G., and Porter, L. (2016). Lightweight, early iden-

tification of at-risk cs1 students. In Proceedings of

the 2016 ACM Conference on International Comput-

ing Education Research, ICER ’16, pages 123–131,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Moredich, C. and Moore, E. (2007). Engaging students

through the use of classroom response systems. Nurse

Education, 32(3):113–116.

Moss, K. and Crowley, M. (2011). Effective learning in

science: The use of personal response systems with

a wide range of audiences. Computers & Education,

56(1):36–43.

Porter, L., Zingaro, D., and Lister, R. (2014). Predicting stu-

dent success using fine grain clicker data. In Proceed-

ings of the Tenth Annual Conference on International

Computing Education Research, ICER ’14, pages 51–

58, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Simon, B., Parris, J., and Spacco, J. (2013). How we teach

impacts student learning: Peer instruction vs. lecture

in cs0. In Proceeding of the 44th ACM Technical Sym-

posium on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE ’13,

pages 41–46, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Vinaja, R. (2014). The use of lecture videos, ebooks, and

clickers in computer courses. J. Comput. Sci. Coll.,

30(2):23–32.

Webb, A. and Carnaghan, C. (2006). Investigating the ef-

fects of group response systems on student satisfac-

tion, learning and engagement in accounting educa-

tion. Issues in Accounting Education, 22(3).

Zingaro, D. (2014). Peer instruction contributes to self-

efficacy in cs1. In Proceedings of the 45th ACM

Technical Symposium on Computer Science Educa-

tion, SIGCSE ’14, pages 373–378, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Zingaro, D. and Porter, L. (2015). Tracking student learning

from class to exam using isomorphic questions. In

Proceedings of the 46th ACM Technical Symposium

on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE ’15, pages

356–361, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

24