Community Building among Older Adults in a Digital Game

Environment

Robyn Schell and David Kaufman

Education, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Dr, Burnaby, BC, V5A1S6, Canada

Keywords: Community Building, Digital Games, Will Bowling, Older Adults, Social Connections.

Abstract: This research study describes the social connections made by a group of older adults participating in a city

wide Wii bowling tournament. Our results showed that participant’s experienced an increased level of social

connectedness with not only those who played with them weekly but others where they lived, their friends

and family members outside of the places where they lived. Overall, the participants found that playing Wii

bowling in a tournament setting contributed to the expansion of their existing network and deepened

relationships in the players’ community by extending the level of social connectedness both within the game

environment and beyond the boundaries of the game space.

1 INTRODUCTION

Improvements in public health and welfare have

resulted in people living longer and healthier lives

(Phillipson, 2013), yet certain aspects of ageing can

be very difficult especially when one is faced with

chronic illness and the loss of life-long friends and

partners. There is evidence to show that engagement

in social activities can have a positive influence on

physical activity, and maintaining cognitive function

(Rowe and Kahn, 1997). Brookfield also suggested

that learning activities can contribute to community

development through the facilitation of peer support

within learning groups that share common goals

(Brookfield, 2012). Merriam and Kee expanded

upon these ideas, arguing that as older adults gain

more knowledge and become more socially engaged,

both their personal and community wellbeing are

enhanced (Merriam and Kee, 2014).

Being part of a social community can create

positive feelings of self esteem and self worth and

having a purpose in life (Cohen, 2004). Developing

social relationships are also thought to relieve stress

by providing support in times of need either directly

or indirectly (Cohen et al., 2000). Indirectly, social

relationships provide resources whether

informational, emotional, or tangible which help to

reduce the acute or chronic stress brought on by life

events. Building social relationships may be also

associated with protective health benefits through

more direct means by influencing cognitive,

emotional, behavioural, and biological effects that

are not explicitly intended to provide help or support

(Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

New types of relationships within communities

are emerging within the diverse contemporary

structures of society, resulting in an availability of

connections within a broader social milieu than

before. There are opportunities for intergenerational

exchanges as generations are more likely to overlap

and interact (Marshall et al., 1993). Social ties with

friends also offer a new source of significant

relationships in one’s community.

Although the lives of older people are generally

viewed within the family context in terms of support

and care, non-kin ties are becoming more influential

in the lives of older adults (Beck, 2000). This can be

partly attributed to the growth of single person

households and the growth of numbers of people

who live alone (Klinenberg, 2012). It is now more

likely that older adults will develop a myriad of

social relationships among a variety of connections

that some have referred to as personal communities

consisting of friends, neighbours, and other

acquaintances who give and receive help at different

points in life (Phillipson, 2013). In some cases

friends are replacing family as sources of support in

old age. These relationships of choice can be critical

in enhancing mental health (Phillipson et al., 2000)

as well as informal support. The development of

new forms of relationships across age groups and

social groups and outside of kinship groupings has

Schell, R. and Kaufman, D.

Community Building among Older Adults in a Digital Game Environment.

DOI: 10.5220/0006253202330239

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 233-239

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

233

changed the composition and dynamics of the social

life of older people.

As social engagement has been identified as

significant component of successful ageing, it is

possible that participation in meaningful leisure

activities with others can create social environments

that foster community building among older adults.

Playing digital games has been noted as a leisure

activity that has potential to alleviate loneliness and

enhance social connectedness among older adults

(Whitcomb, 1990; Ijesselsteijn et al., 2007;

Gamberini et al., 2009; Allaire et al., 2013; de

Schutter and Abeele, 2010, Schell et al., 2015).

Digital games can also encourage and scaffold

learning among the players (Gee, 2003) and as such

could have the potential to support the concept of

lifelong learning which has been associated with

promoting and preserving community (Merriam,

2014).

This paper discusses the concept of digital

gaming as a social activity which can expand the

social network of older adults within their

community. Previous work has been primarily

focussed on younger people and when focussed on

older adults often centers on cognitive and physical

effects rather then psychosocial effects described in

this paper. The study involved personal interviews

of 17 older adults who played in a city-wide Wii

Bowling tournament drawn from a quantitative

study of 73 participants.

Next, we further explore the social and learning

aspects of digital games for older adults.

2 SOCIAL ASPECTS OF DIGITAL

GAMES

Older adults have become significant consumers of

technologies including digital games (ESA, 2011).

Games have been associated with a number of

positive attributes. For example, developing skills

and mastering a game can create a sense of

accomplishment (IJsselsteijn et al., 2007). The sense

of losing track of time and immersion, called “flow”,

that people experience when they are totally

involved in playing a game has the potential to

create feelings of enjoyment and satisfaction

(Csikszentmihalyi, 1997).

When games include social interaction, they may

also create a venue for enhancing the social lives of

older adults and provide a social activity that can be

effective in reducing loneliness and social isolation

(Cattan et al., 2005). Technology may be useful in

supporting and developing social connections

(Baecker et al., 2012) and since loneliness is

believed to be a deficit in the broader range of social

contact (Heylen, 2010), expanding the social

network through digital games may provide benefits.

An early pioneer in game research, Whitcomb

noted that social interaction was the most important

benefit for older adults playing digital games (1990)

and the feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment

associated with playing a digital game positively

affected people’s perception of themselves.

Whitcomb identified physical and cognitive benefits

such as improved hand-eye coordination, manual

dexterity, and increased speed with playing the game

as possibly enhancing the self perceptions of older

adults. More recently, Ijesselsteijn et al (2007)

suggested that gaming could enhance the lives of

older adults by providing opportunities for

relaxation and entertainment, socializing, sharpening

the mind, as well as offering a more natural way of

interacting.

Gamberini et al. (2009) examined the user

experience of older adults along seven key

dimensions including social interaction, playability,

immersion, challenge/skills, and clear goals using a

game prototype called Eldergames intended to

improve older people’s quality of life. The study

involved 107 participants who responded to a

questionnaires and a focus group over the 12 weeks

of testing. Although the emphasis of this study was

on cognitive training, these researchers found the

game also promoted interaction creating a positive

social experience for the users.

Voida and Greenberg (2012) described playing

Wii as a computational meeting place for older

people to establish social contacts with peers and to

experience intergenerational play. Both peer-to-peer

mentoring and learning in informal environments

can create the circumstances that enhance computer

literacy (Selwyn, 2005) and promote the learning of

digital games themselves and in the process reduce

the anxiety around technology and increase feelings

of self efficacy and self-confidence among older

people.

3 DIGITAL GAMES AND

LEARNING

As well as encouraging social connections, playing

games can provide an environment for learning.

Lifelong learning has been associated with improved

cognitive function, supporting social interaction in

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

234

society (Withnall, 2012) as well as sustaining

physical and psychological wellbeing (Sloane-Seale

& Kops, 2008). Lifelong learning can also offer new

experiences that reduce stress and provide escape

from life’s problems (Dattilo et al., 2012). Research

suggests that collaborating with others can stimulate

learning and help build a community of practice

(Wenger, 1998; Kaufman et al., 2011), and that

problem solving is an activity that provides learning

opportunities (Boud and Feletti, 1998). There are

many examples of games which feature problem

solving as a mechanism for game play as well as

presenting an environment for social interaction. Wii

bowling is a strategy game that can involve

collaborating with others in a social milieu.

4 THE Wii BOWLING

TOURNAMENT

Our research focused on a digital game that many

have played or are familiar with, Wii Bowling,

published by Nintendo in 2006. Wii Bowling is one

of a suite of games called Wii Sports which is one of

the best selling games of all time (Nintendo Investor

Relations Information, 2014). The Wii remote

device contains sensors that detect natural body

movements that are mirrored within the game play

itself. Virtual bowling can allow older adults to

participate in activities they may not be able to do

because of reduced mobility or strength.

When playing Wii Bowling, the players use a

handheld controller to simulate the motions that

occur in an actual Bowling game. The format of a

Wii Bowling tournament was selected to encourage

people to join the project, create a venue

traditionally associated with bowling, and provide a

motivating team setting that offered an opportunity

for cooperative game play. Research has shown

cooperative learning offers social benefits such as

improving relationships, facilitating learning new

skills, and enhancing the ability of working with

others but these goals can only be achieved when

there is a group goal that is important to those in the

group (Slavin, 1988). Competing in the tournament

may provide that essential common group goal that

leverages these benefits.

During each Bowling session, participants played

two full games of Wii Bowling. The Research

Assistants recorded the scores and posted them on a

tournament website and announced the next game

date and time.

5 PARTICIPANTS

The participants who joined in the eight-week

tournament were recruited from 14 centers where

older adults lived or frequented in the Vancouver

Lower Mainland area including independent living

centers, senior recreation centers, and assisted living

centers. After receiving permission, our study was

advertised through posters posted by staff in each

location. Our goal was to recruit those over 60 years

of age or older. Independent living centres offer

apartment living for those over 55 years of age,

while assisted living centres offer additional services

to residents such as meals, housekeeping, laundry,

recreational opportunities, 24-hour response lines,

and personal care services. The 17 participants

recruited for our qualitative research lived in

independent living centers while five others lived in

assisted living centers. These 17 participants were a

subset of a group of 73 people who took part in a

larger quantitative study.

6 RESEARCH DESIGN

The study’s qualitative approach was designed to

answer our research question “What do the

participants perceive as the social benefits of playing

the digital game Wii Bowling in a tournament?”.

This research question was explored through

interviews with participants that elicited players’

perceptions and opinions of their game playing

experience. During these one-on-one interviews, we

asked about players’ reports of connections and

friendships they formed during the tournament, and

their interactions and conversations with others

about their involvement in the tournament.

7 DATA COLLECTION

Data was collected through recorded interviews with

seventeen participants at their center or in their

home. Each interview lasted for about 30 minutes

and addressed topics designed to elicit perceptions

of the game playing experience and the formation of

friendships or social connectedness with their team

members, their family and friends, and others in

their centers due to playing in the Wii Bowling

tournament.

Community Building among Older Adults in a Digital Game Environment

235

8 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF

PERSONAL INTERVIEWS

These interviews were recorded, transcribed, and

analyzed using qualitative software MaxQDA

Version 11 to code statements and identify themes.

Data analysis involved preparing and organizing text

transcriptions of interviews, and collecting the codes

into themes, then illustrating each theme by actual

quotes made by the participants (Creswell, 2007).

The specific steps taken were writing codes and

memos, noting patterns and themes, counting

frequency of codes, developing evidence, and

making comparisons (Miles et al., 2014).

9 CODING PROCESS

Coding methods are divided into two categories: the

first cycle and second cycle of coding. The first

cycle includes Elemental Methods that encompasses

three types of coding used for this research:

structural, descriptive, and process coding (Saldana,

2009). This selection of two or more types can serve

the goals of the analysis since coding methods are

not discrete but overlap in applicability (Saldana,

2009).

The first cycle of coding provided a method for

summarizing segments of the data. Pattern coding

grouped these codes into smaller number of

categories or themes (Miles et al., 2014) compiled

into a table that shows the codes, number of times

the codes was applied, and the number of

participants who had this code applied to their

comments. This table is shown below. To determine

predominant themes, we highlighted those

statements where 50% of the total number of

participants (n= 17), had made comments that

received that specific code. This number was

considered the cut off for codes that would be

reviewed and discussed in detail in the findings.

We also noted those instances where participants

had commented on a theme multiple times during

the interview process. For example, there were 10

participants whose statements were coded with the

same code 50 times. Where themes were generated

according to number of people but where there were

a similar number of people, the number of times the

code came up was used to break the tie. To

triangulate the qualitative results, peer review of

methodology was requested and completed, as well

as a member check of the findings by participants

representing each centre.

10 FINDINGS

Of the seventeen participants interviewed after the

tournament, three were males and 14 were female.

Five participants lived in assisted living

accommodation and twelve lived independently.

Five participants were between 65 and 74 years old;

eight were 75 to 84 years old and four were 85 years

old and older. One person was 90 years old. Social

connectedness was a major theme in the participant

interviews. Table 1 shows these results in terms of

each code and the number of people making

comments with this code, and how many times this

code was applied in the text. Through this analysis,

one could consider the level of consensus among

these participants and how predominant that theme

appears to be.

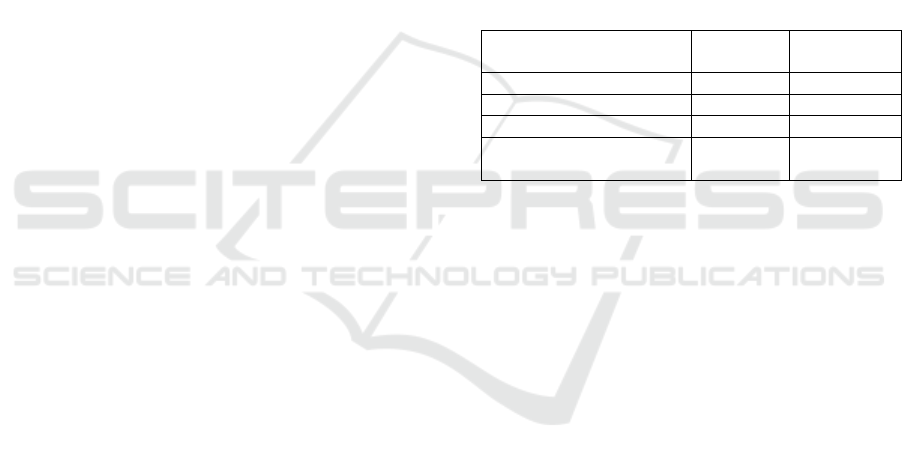

Table 1: Theme of Social Connectedness.

Code # of people

# times code

applied

Team Experience 17 37

Interaction with Others 16 84

Better Social Connections 13 70

Conversations about game

with family and friends

13 49

11 DISCUSSION

The majority of participants interviewed found that

playing in the Wii Bowling tournament brought

about new or closer friendships with other players,

as well initiated interactions with other members in

their community beyond the scope of the actual

tournament itself. Playing Wii Bowling also led to

interactions outside the game environment and

expanded social connections for participants beyond

the weekly Wii Bowling sessions. These interactions

included conversations with fellow players after

game sessions, participating in outside activities

such as going to dinner, or going to church together,

as well as playing other games with people they met

in and outside of the tournament.

Our study seems to indicate that playing Wii

Bowling was an enjoyable way for older adults to

interact, and deepen bonds with those they already

knew casually or were acquainted with in the

community where they lived.

We also found that playing Wii brought about

intergenerational play among friends and relatives

which was an unexpected finding as the focus of our

study was on the social impact of playing with peers.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

236

This older group of players independently selected

to play Wii Bowling with younger family members

including their grown children and grandchildren or

had conversations with them about their experience

in the tournament. Our participants noted that

playing with adult children or grandchildren added a

welcome dynamic to family relationships which

substantiates earlier findings that intergenerational

interaction offers the opportunity to extend the

diversity of people in one’s personal network.

Diversity is a factor that has been identified as

strengthening social interconnectedness in one’s

greater social network (Voida & Greenberg, 2012).

Non-family members such as neighbours and friends

who become part of the social network of older

adults also provides a source of social support

especially when relatives are not readily available

(McPherson, 2004) so from this point of view,

playing digital games with team members and others

in their community could provide social benefits that

can be important to older adults as families become

more distributed and more dependent on non-kin

relationships.

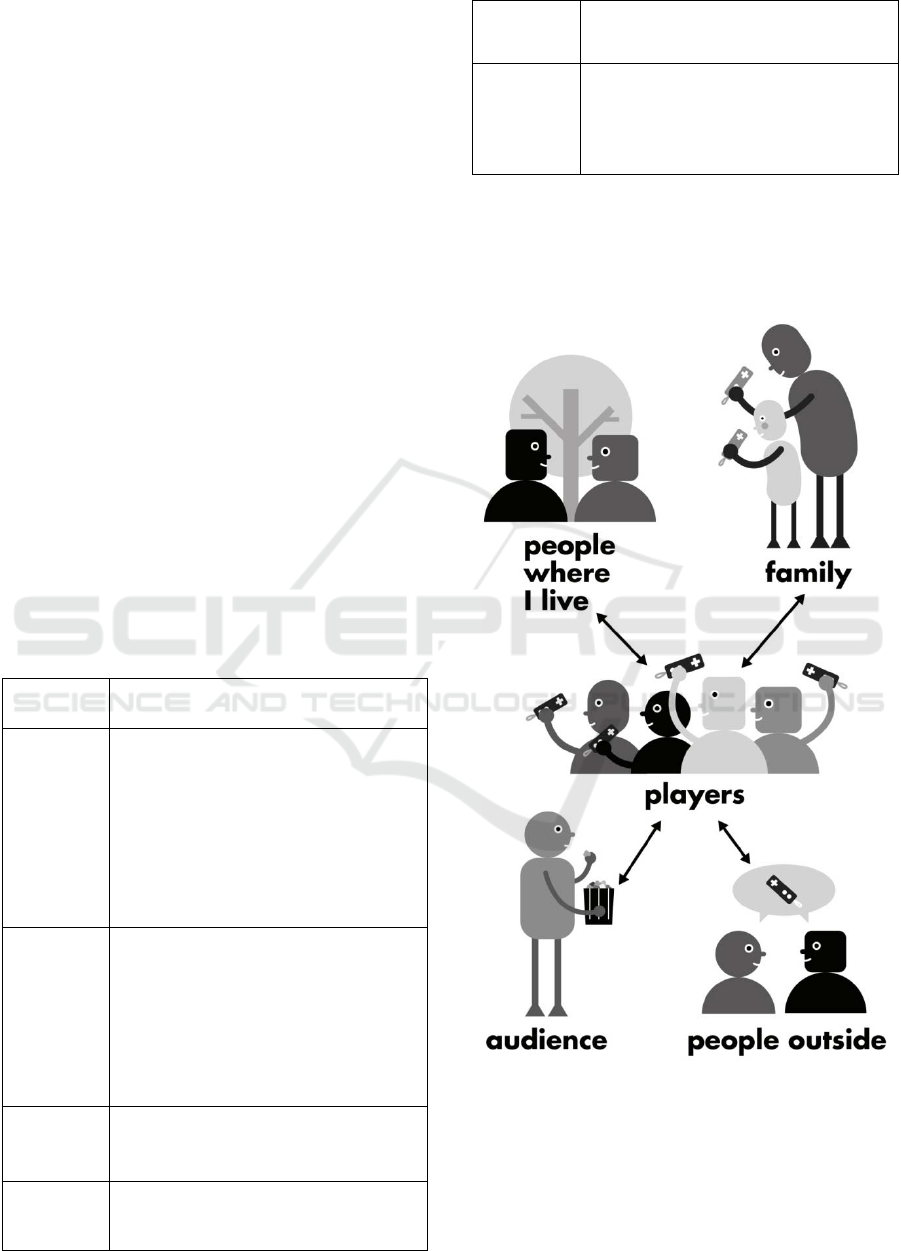

The following table shows samples of a type of

community contact made during the Wii Bowling

tournament and example of the coded text related to

this contact.

Table 2: Social Connections Made in Wii Bowling.

Community

contact

Sample Interview Code

People

outside where

I live

Well, a lot of my friends thought it was

really funny. You know, “[Oh wait] (?)

You’re Bowling on”; “Yes, I am. I bowl—

I’m doing Wii Bowling.” “Oh, [wow] (?)”

um, most of my friends are pretty active

people. They swim or they go to the gym.

They play golf. They play tennis, some of

them. So, it was—it was interesting for

them to think that I would do this.

Family

Oh, it’s kind of fun because my—I took

my son down and his wife down Bowling

there. And he used to be pretty good and

so, you know, I’d just lean on here and

pssshhht. Boom. Boom. Getting 200 plus.

So he was curving all around the place and

there. So, anyhow, he got a little bit

frustrated.

Audience

members

Because we had people come to watch.

Because they showed interest, they thought

"what are they up to now."

Other people

where I live

Which is something we might not have

done, but because we--there’s four of us

and we brought another member who

doesn’t bowl, but belongs in our little

group, we went out together and had a

meal together. So in that respect it was fun.

Other players

Getting to know your teammates, right.

Then, you know, when you see them, you

sort of –well, you feel part of them Right?

So it brings the camaraderie between you,

you know.

Figure 1 illustrates the social connections referred to

by the Wii Bowling tournament participants

showing that their involvement had extended these

connections beyond the scope of the game sessions

themselves and into the wider community.

Figure 1: Model of Social Connections.

As Voida and Greenberg (2009) described, the

digital game space is a computational meeting place.

In the tournament context, playing digital games acts

not only as a place to gather and play, but also an

activity that fosters connections and builds

community beyond the game and so brought more

Community Building among Older Adults in a Digital Game Environment

237

people into the orbit of this social event through

conversations, or as spectators, regardless of

whether they actually played or were physically

present. Of course, the dynamics of games like Wii

Bowling change as people play them. As such the

social connections made during the tournament

depend on how the game unfolds as well as the

people who are playing at that time (De Schutter and

Abeele, 2010).

12 CONCLUSIONS

In our research, we saw evidence that those who

participated in the Wii bowling tournament

perceived playing in the Wii tournament as an

opportunity to meet others in a team environment

and well as extend their social connections into their

community. They also acquired the technical ability

to play this game with their peers. In a sense, they

formed a community of practice in which players

learned the game and improved their ability to play.

Through their participation, these players shared an

activity and common interest that provided the

environment for social learning and deeper

understanding of other players (Wenger, 1998) that

we saw reflected in interviews with our participants.

Squire (2011) refers to video games as shared spaces

where people develop expertise, social experiences,

and make social connections. This assessment seems

to be in line with the experiences of the older adults

who played in our Wii Bowling tournament.

We are not claiming that playing Wii Bowling

provided more social opportunities than other

traditional recreational activities for older adults;

however, our results suggest that playing Wii

Bowling extended relationships beyond the time and

place where the game occurred, even in centres

where people already knew their fellow players and

audience members. We believe our study added to

the literature in terms of participants, goals, and

parameters. The majority of our players included

older individuals over 75 years of age. This study

focussed on a readily available commercial game

and social impact rather than unique games and

other factors. For example, Gaberini et al’s (2009)

Eldergames that studied cognitive training and Age

Invaders by Khoo et al. (2009) which investigated

intergenerational play.

This study provides a deeper understanding of

the social effects of playing digital games for older

adults and offers information that might lend itself to

further investigation of digital games as a

mechanism that facilitates community building

especially among the oldest of the old or those who

suffer from mobility issues. Other studies could

focus on the potential of digital games to provide a

situated learning environment for increasing

technical skills among older adults that focuses on

game players as a community of practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the AGE-WELL National Centre

of Excellence for their financial support of this

paper.

REFERENCES

Allender, S., Cowburn, G. and Foster, C., 2006.

Understanding participation in sport and physical

activity among children and adults: A Review of

Qualitative Studies. Health Education Research, 21,

pp. 826-835.

Allaire, J., McLaughlin, A., Trujillo, A., Whitlock, L.,

LaPorte, L., & Gandy, M. (2013). Successful aging

through digital games: Socioemotional differences

between older adult gamers and non-gamers.

Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 1302-1306.

Astell, A. J. (2013). Technology and fun for a happy old

age. In A. Sixsmith, & G. Gutman (Eds.),

Technologies for active ageing (pp. 169-187). New

York: Springer.

Baecker, R., Moffatt, K., & Massimi, M. (2012).

Technologies for aging gracefully. Interations, 19(3),

32-36. doi:10.1145/2168931.2168940Brookfield, S.

(2012). The impact of lifelong learning on

communities. In D. Aspin, J. Chapman, K. Evans & R.

Bagnall (Eds.), Second international handbook of

lifelong learning (pp. 875-886). New York, NY:

Springer.

Beck, U. (2000). Living your own life in a runaway world:

Individualization, globalization, and politics. In W.

Hutton, & A. Giddens (Eds.), On the edge: Living

with global capitalism (pp. 164-174). London:

Jonathan Cape.

Boud, D. & Feletti, G. (1998). The challenge of problem

based learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brookfield, S. (2012). The impact of lifelong learning on

communities. In D. Aspin, J. Chapman, K. Evans & R.

Bagnall (Eds.), Second international handbook of

lifelong learning (pp. 875-886). New York, NY:

Springer.

Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005).

Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older

people: A systematic review of health promotion

interventions. Ageing & Society, 25(01), 41-67.

doi:10.1017/S0144686X04002594.

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, H. H., & Underwood, L. G. (2000.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

238

Social relationships and health. In S. Cohen, B. H.

Gottlieb & L. G. Underwood (Eds). Measuring and

intervening ni social support: A guide for health and

social scientists (pp. 3-25). New York: Oxford

University Press.

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health.

American Psychology, 59, 676-684.

Creswell, J. W.. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research

design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.).

Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and education.

NAMTA Journal, 22(2), 2-35.

Dattilo, A., Ewart, A., & Datillo, J. (2012). Learning as

leisure: Motivation and outcome in adult free time

learning.Journal of Parks and Recreation

Administration, 34 (1), 1-18.

De Schutter, R., & Abeele, V. (2010). Designing

meaningful play within the psycho-social context of

older adults. Fun & Games, (September), 13-15.

Entertainment Software Industry. (2011). Essential facts of

computer and video game industry. Retrieved from

http://www.theesa.com/facts/pdfs/ESA_EF_2011.pdf.

Gamberini, L., Martion, T., Seaglia, B., Spagnolli, A.,

Fabregat, M., Ibanez, F., . . . Andres, J. (2009).

Eldergames project: An innovative mixed reality table-

top solution to preserve cognitive functions in elderly.

HSI '09 2nd Conference on Human System

Interactions, Catania, Italy. 164-169.

Gee, J.P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us

About Learning and Literacy. New York, NY, St

Martin's Press.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010).

Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-

analytic review. PLoS med 7(7): e1000316.

doi:10.1371/ journal.pmed.1000316. PLoS Med, 7(7),

e1000316-e1000316. doi:10.1371/

Heylen, L. (2010). The older, the lonelier? Risk factors for

social loneliness in old age. Ageing & Society, 30,

1177-1196.

IJsselsteijn, W. A., Nap, H., de Kort, Y., & Poels, K.

(2007). Digital game design for elderly users.

Proceedings of 2007 Conference on Future Play, The

Game Developers Conference, Toronto, Canada. 17-

22.

Kaufman, D., Sauve, L., & Renaud, L. (2011). Enhancing

learning through an online secondary school

educational game. Journal of Educational Computing

Research, 44(4), 409-428.

Khoo, E., Merritt, T., & Cheok, A. (2009). Designing

physical and social intergenerational family

entertainment. Interacting with Computers, 21, 76-87.

doi:10.1016/j.intcom.2008.10.009.

Klinenberg, E. (2012). The extraordinary rise and

surprising appeal of living alone. New York: Penguin.

Marshall, V., Matthews, S., & Rosenthal, C. (1993).

Elusiveness of family life: The challenge of the

sociology of aging. In G. Maddox, & L. Powell (Eds.),

Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 39-

72). NY: Springer.

McPherson, B. D. (2004). Aging as a social process:

Canadian perspectives (4th ed.). Don Mills, Ont.:

Oxford University Press.

Merriam, S. B., & Kee, Y. (2014). Promoting community

well-being: The case for lifelong learning for older

adults. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(2), 128-144.

doi:10.1177/0741713613513633.

Miles, M., Huberman, M., & Saldana, J. (2014).

Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd

ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Nintendo Investor Relations Information. (2014). Top

selling software sales units: Wii. Retrieved from

http://www.nintendo.co.jp/ir/en/sales/software/wii.htm

l.

Phillipson, C. (2013). Ageing. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Phillipson, C., Bernard, M., Phillips, J., & Ogg, J. (2000).

The family and community life. London: Routledge.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging.

Gerontologist, 37(4), 433-440.

Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative

researchers. London: Sage Publications.

Savery, J. R. & Duffy, T. M. (1995). Problem-based

learning: An instructional model and its constructivist

framework. Educational Technology, 35(5), 135-150.

Schell, R. M., Hausknecht, S., Zhang, F., & Kaufman, D.

M. (2015). Social benefits of playing wii bowling for

older adults. Games and Culture, 11(1-2), 81-103.

Selwyn, N. (2005). The social processes of learning to use

computers. Social Science Computer Review, 23(1),

122-135.

Slavin, D. (1988). Cooperative learning and student

achievement. Educational Leadership, 46(2), 31-34.

Sloane-Seale, A., & Kops, B. (2008). Older Adults in

Lifelong Learning: Participation and Successful

Aging. Canadian Journal of University Continuing

Education, 34(1), 37–62.

Squire, K., Jenkins, H. (2011). Video games and learning:

teaching and participatory culture in the digital age.

New York: Teacher's College Press.

Voida, A., & Greenberg, S. (2012). Console gaming

across generations: Exploring intergenerational

interactions in collocated console gaming. Universal

Access in the Information Society, 11, 45-56.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: learning,

meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Whitcomb, R. (1990). Computer games for the elderly.

Proceedings of the Conference on Computers and the

Quality of Life (CQL '90), ACM, New York, NY,

USA. , 20(3) 112-115. doi:10.1145/97344.97401.

Withnall, A. (2012). Lifelong or longlife? Learning in the

later years. In D. N. Aspin, J. Chapman, K. Evans, R.

Bagnell (Eds.), The handbook of adult and continuing

education, 2010 edition (pp649-664). New York, NY:

Springer.

Community Building among Older Adults in a Digital Game Environment

239