A Case Study on the Importance of Peer Support for e-Learners

Elizabeth Sinclair

The University of the West Indies, Open Campus, Programme Delivery Department,

Academic Programming and Delivery Division, Mona, Jamaica

Keywords: Peer Support, Learner Support, Distance Education, e-Learning.

Abstract: The purpose of this research is to examine the importance of peer support among a group of post-graduate

students in an online programme. Surveys were administered and interviews conducted with Dominicans

from a particular cohort; keeping cultural background and occupation as constants. Results showed that

students place great emphasis on the importance of peer support; where more than half of the respondents

explicitly stated that their peers are helpful to them regarding educational needs, such as finishing their

degree and passing their courses. This case study emphasizes the importance of peer support and encourages

administration to implement other methods of facilitating peer support between and among cohorts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Students undoubtedly have competing demands

when studying online. Administrators, teachers and

facilitators of online learners must ensure they create

a teaching-learning environment for educational

success. In accordance, finding ways to encourage

peer interaction and support is one of the keys to

online learning success. Online students develop

community, construct understanding, and question

and clarify content through discussion with other

learners (Shackelford and Maxwell, 2012).

Wright (1991) as quoted by Robinson (1995)

defines support as “the requisite student services

essential to ensure the successful delivery of

learning experiences at a distance”. Some

researchers refer to support as an integral aspect of

the e-learning process, while others merely mention

it as appendage. However, Zawacki-Richter (2004)

speaks to the growing importance of support for

learners and faculty in online distance education,

stating that in contrast to face-to-face teaching,

distance education in general puts more

responsibility on the learners to manage their own

learning; online learning requires more

competencies (e.g. media literacy) and skills from

learners and these need to be developed; and it is

especially important to provide faculty support

structures to promote, develop and implement online

distance learning and teaching. He goes further to

state the importance of offering distance learners

additional forms of support in order to ensure

successful online learning experiences (Zawacki-

Richter, 2004).

Boud et al., (2002) define peers as “people in a

similar situation to each other who do not have a role

in that situation as teacher or expert practitioner;

they may have considerable experience and expertise

or they may have relatively little; they share the

status as fellow learners and they are accepted as

such. Most importantly, they do not have power over

each other by virtue of their position or

responsibilities.” Support can take the form of

“personal contact between learners and support

agents (people acting in a variety of support roles

and with a range of titles), individual or group, face-

to-face or via other means; peer contact; the activity

of giving feedback to individuals on their learning;

additional materials such as handbooks, advice notes

or guides; study groups and centres, actual or

'virtual' (electronic); access to libraries, laboratories,

equipment, and communication networks”

(Robinson, 1995).

Learner-learner interactions take place “between

one learner and other learners, alone or in group

settings, with or without the real-time presence of an

instructor” (Moore, 1989 as cited by Su et al., 2005).

Many studies show that this type of interaction is a

valuable experience and learning resource, while

empirical evidence shows that students actually

desire learner-learner interactions, regardless of the

delivery method (Su et al., 2005).

280

Sinclair, E.

A Case Study on the Importance of Peer Support for e-Learners.

DOI: 10.5220/0006263602800284

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 280-284

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Ludwig-Hardman and Dunlap (2003) found that

some of the main factors, which contribute to

attrition, are level of interaction and support. They

found that some students in distance learning

programs and courses report feelings of isolation,

lack of self-direction and management, and eventual

decrease in motivation levels (Ludwig-Hardman and

Dunlap, 2003). They implemented a scaffolding

approach, which included an orientation to the

online learning experience/ environment, one-on-one

advising, and access to a community of learners.

Tait (2014) cited Street (2010), who stated time,

pressure, self-management, family, logistics and

support (including technical support) and curriculum

relevance, as the major causes of failure to progress

in online learning. He then further added inadequate

educational preparedness as a factor, and noted that

these barriers to success, lying both within and

outside the institution’s direct control, must be

acknowledged to determine how students should be

supported (Tait, 2014). Shackelford and Maxwell

(2012) stated that there is still no substitute for

interaction, and there must be opportunities for

students to interact in multiple ways with their peers

in an online environment.

This study has chosen to closely examine peer

support. At The University of the West Indies, Open

Campus (UWIOC), peer support is widely

encouraged by teaching and administrative staff.

Research supports the development of community in

online learning as an important factor for

maximizing student satisfaction with the experience

(Liu et al., 2007; Ouzts, 2006 and Rovai, 2002, as

cited by Shackelford and Maxwell, 2012).

For the Master's’ programmes at the UWIOC,

students must take a three-week graduate

introduction to online learning course, before

beginning their programme of study. This course

includes twelve compulsory activities which aim to

orient students to online learning, teaches skills in

navigating the Moodle course management system

(CMS) and enhancing the capacity to learn by

interacting / engaging with peers. Further, it aims to

equip students with skills for self-directed learning,

skills for writing academic papers and gives students

basic skills for engaging in Blackboard Collaborate

web conferencing sessions. Students in each

programme are regularly invited to meetings with

their Programme and course teams (at least three per

semester); where a team consisting of the

Programme Manager, Course Delivery Assistant,

Online and Distance Learning Instructional

Specialist and Learning Support Specialists, hear

their concerns and address issues. The Programme

Manager also has an “open door policy” where

students can contact them at any point in time, and

provides one-on-one advising as necessary.

2 METHODS/ PROCEDURE

The particular cohort chosen for this case study

consists of 25 Dominican students studying online

for their Master of Science degree. This group was

chosen as they have a 100% retention rate (with only

two semesters remaining for the programme), and

have performed excellently in their programme with

5 out of their 10 courses thus far having had a 100%

pass rate (Table 1). All students are employed in the

field of Education as principals, vice principals or

senior teachers. Due to the success that this group

has exhibited, it is felt that further observations and

data obtained, could be used as a model to assist in

encouraging student support, and ultimately student

retention and success. Further, this group was

chosen, as all participants reside in the same country.

The UWIOC generally has students from 17

countries where students often form relationships

with peers via the Moodle course forums, skype,

social media or otherwise. Studying this group can

reveal if peer support is preferred and/or most

effective face-to-face or online. All students either

know their peer(s) prior to the start of the

programme, or met face-to-face during orientation.

They have therefore had the opportunity to interact

in person for group work or personal study groups

(unlike the typical UWIOC students), greater ease of

communication such as telephone calls, and access

to meet in person as desired. Students voluntarily

engaged in informal interviews via skype (subject to

availability) and were asked to complete an

anonymous online survey. Data was gathered over a

period of 8 weeks in the middle of the semester

based on subject availability.

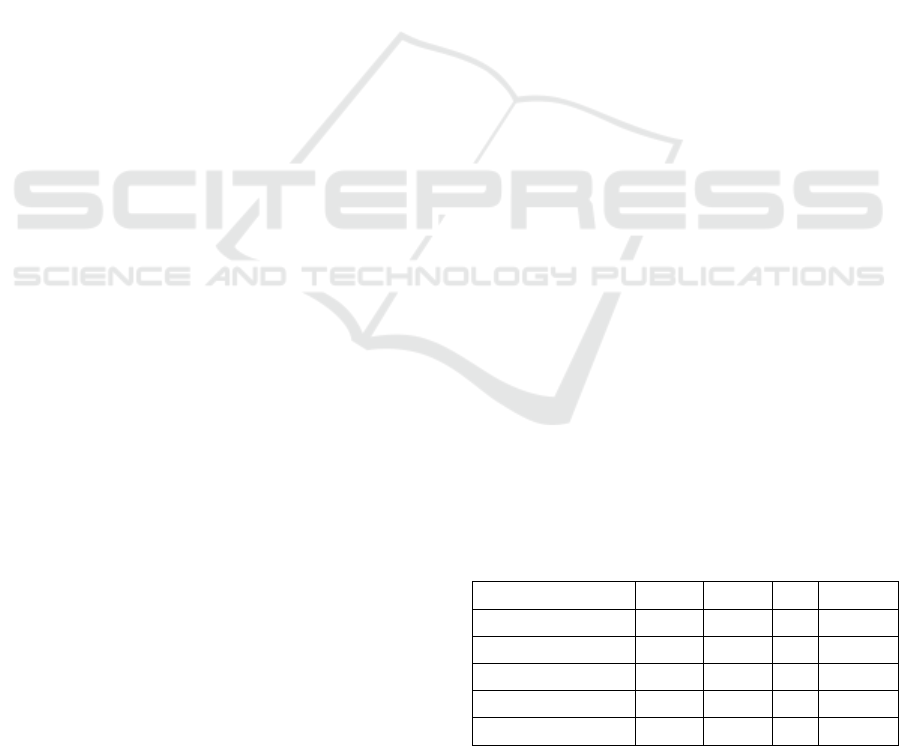

Table 1: Grades obtained by students in five courses done

to date.

Course code A B+ B Pass

MGMT6019 15 8 2 25

MGMT6202 22 3 0 25

MGMT6206 22 3 0 25

EDLM6004 25 0 0 25

EDLM6005 25 0 0 25

A Case Study on the Importance of Peer Support for e-Learners

281

3 RESULTS

Of the 25 students asked to complete the survey, 22

responded (72.7% or 16 females and 27.3% 6

males). 63.6% of respondents are between the ages

of 40-49, while 27.3% are 50-59 years old; and 9.1%

are 30-39 years old. Exactly half (50%) of the

respondents are married or in a common-law

relationship, while 45.5% are single and 4.5% are

divorced/ separated. When asked “How many

children under the age of 18 live with you at least

four days per week?”; 54.5% said none, 31.9% said

one child, and 13.6% said two children. The gender

ratio is reflective of many programmes at the

UWIOC and so this factor was not considered. In

addition, because marital status and family

compositions seemed evenly divided, this factor was

also not taken into consideration.

When asked if they receive help with

coursework, 76.2% stated they receive help from

peers in their programme. Other responses were;

staff in the programme; friends; family; and

coworkers. 59.1% of students surveyed, stated that

they turn to their peers when faced with difficulties.

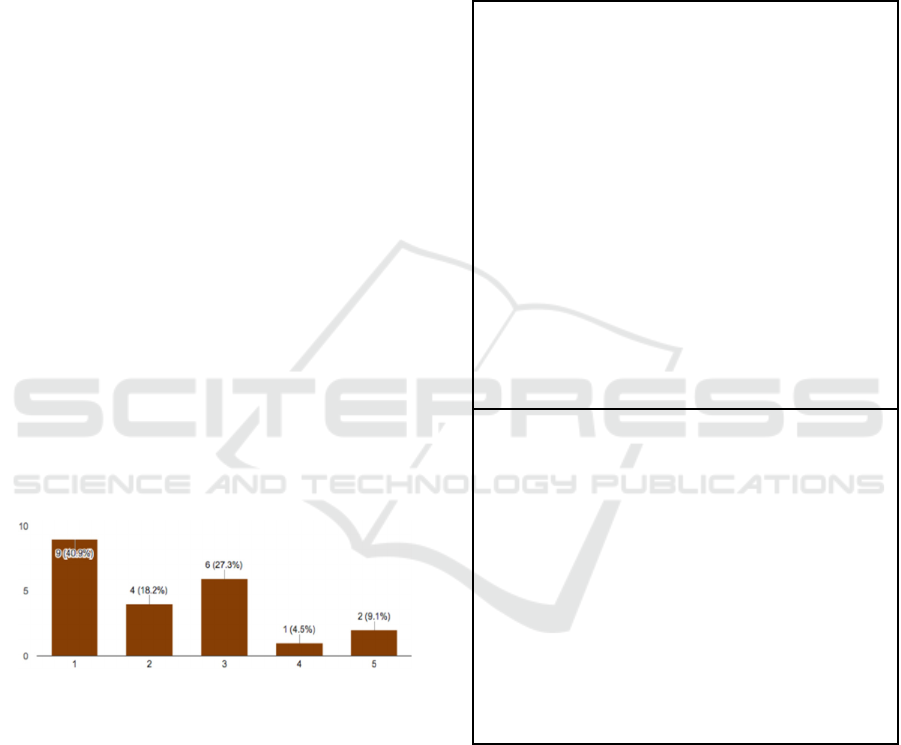

Other results which support the hypothesis that peer

support is an integral asset for students (and their

success) in this programme, are reflected in Figure 1

below, where 40.9% of students strongly agree

(Scale: 1-5 strongly agree to strongly disagree) that

their peers are helpful regarding their educational

needs.

Figure 1: My peers are helpful to me regarding my

educational needs, such as finishing my degree and

passing my courses.

Students in this cohort seem to generally have a

good relationship. When asked if they get along,

54.5% strongly agree, 18.2% agree, 22.7% were

undecided/ neutral and 4.5% disagreed. Further,

when asked how important is receiving support from

their peers on a scale of 1-5 from very important (1)

to not important at all (5); 36.4% rated 1, 27.3%

rated 2, 22.7% rated 3, 9.1% rated 4, and 4.5% rated

5. This 4.5% represents one student. With over 60%

of students expressing the importance of peer

support, the results are aligned with literature that

states that the development of community in online

learning is an important factor for maximizing

student satisfaction with the experience. Very

importantly, almost all students agreed that their

peers are in good positions to understand what they

are going through; with 50% of students strongly

agreeing. Once again, only one student disagreed.

Table 2: Qualitative responses from informal interviews.

Students were asked to list ways in which their peers assist

them. Responses include:

● Explaining assignments with which I might have

difficulty. Encouraging me to hold on.

● Reminders when assignments are due

● Study groups

● We discuss assignments, call each other, look out

for each other. For example, if we are missing from

Blackboard Collaborate (BbC) sessions, etc.

● They explain assignments, we share ideas,

encourage one another to work along, call each

other to find out what assignments need to be done,

or where you are at, study as a group

● Take me home after the late night BbC

● Clear misconceptions regarding assignments

● Offering advice on almost any issue. Meet over

lunch to just relax and recharge

● Cried with me, explain to me what I couldn't

understand, shared information with me, kept me

on track, showed me how to do something, shared

material with me, fed me

Student responses about peer support:

● I must say we have a reliable peer group and we

work well with each other

● A common source of support from my peers is

knowing that they are facing the same challenges as

I am regarding juggling online studies with work

and family life. I have introduced my wife to my

peers in order to save my marriage. She has a very

good idea of how demanding this programme is on

family life.

● Liaising with peers is somewhat difficult due to

work, studies and family duties.

● I always go to my peers for help first, because

they’ve been through the course with me and are

more likely to understand my challenges. Then if

we still don’t understand, a group of us will

approach the tutor together.

4 CONCLUSION/ DISCUSSION

Qualitative results obtained from the interviews via

skype, also attest to the importance of peer support

among members of this cohort (see Table 2 above).

Generally, persons rely on their peers for support

and assistance with their studies. They definitely

listed distinct advantages of having peers in the same

country as them and the quality and intensity of peer

support received. This was inclusive of many facets

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

282

from face-to-face study groups, encouragement and

assignment reminders, to transportation. This could

be related to findings by Kemp and Grieve’s (2014)

findings where students had a strong preference for

class discussions to be conducted face-to-face,

reporting that they felt more engaged, and received

more immediate feedback, than in online discussion.

They further found that while online and face-to-

face activities can lead to similar levels of academic

performance; students would rather do written

activities online but engage in discussion in person

(Kemp and Grieve, 2014).

Similarly, students enjoy

engaging in face-to-face support due to more

engagement and immediate feedback, coupled with

the ease of communication.

One person did however state that they find it

difficult to liaise with peers, as they have to juggle

work, studies and family duties. Brindley (1995)

stated that most people can succeed in education,

given the opportunity and the support to do so. She

however went further to state that some students

complete a course no matter what the circumstances

(no support, administrative mistakes, long delays),

and some students drop out no matter what the

circumstances (good support services, well-designed

courses, fast turnaround times)…The majority of

students fall between these two extremes, and it is

for this group that support services may make a

difference (Powell et al., 1990 as cited by Brindley,

1995).

The challenge for the UWIOC is to find ways to

encourage online peer support and implement more

support services. One such means could be to

implement an online peer mentoring system within

cohorts. Another could be to facilitate a “big brother/

big sister system” across cohorts. Further,

encouragement could be given to form face-to-face

networks in each country, where study groups could

be formed, and social events hosted. Greater

attention can be given to the initial contact made

with students during orientation, to encourage group

activities (in and out of the ‘classroom’). Although

the results from this study are not generalizable due

to the small number of students, it sets the stage for

future research.

This sample was drawn from one university, so

results may not apply to students at other

universities. Further, the UWIOC students reside in

17 Caribbean countries. This study only included

students from one country, and one profession and

so may vary across cultures and/ or professions. It is

therefore recommended that future studies include a

wider sample of students, across programmes,

subject areas, countries and educational institutions.

One could also observe the parallels and value of

classroom/ forum interactions and discussions and

its effect on learner retention and satisfaction.

REFERENCES

Boud, D. et al. (2002). Peer learning in higher education:

learning from and with each other. Edited by David

Boud, Ruth Cohen and Jane Sampson. London, UK.

Kogan Page. Available at:

https://web.stanford.edu/dept/CTL/Tomprof/postings/4

18.html [Accessed 23 Nov. 2016].

Brindley, J. E. (1995). Learners and learner services: the

key to the future in distance education. In J.M.

Roberts, and E.M. Keough (Eds.), Why the

information highway: Lessons from open and distance

learning (pp. 102-125). Toronto: Trifolium Books Inc.

Available at: http://www.c3l.uni-

oldenburg.de/cde/support/readings/brind95c.pdf

[Accessed 27 Nov. 2016].

Kemp, N., and Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-

screen? Undergraduates' opinions and test

performance in classroom vs. online learning.

Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 5: 1276. Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC42288

29/ [Accessed 21 Feb. 2017].

Ludwig-Hardman, S., and Dunlap, J. (2003). Learner

support services for online students: scaffolding for

success. The International Review of Research in

Open and Distributed Learning, Vol. 4, No. 1.

Available at:

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/13

1/211 [Accessed 12 Nov. 2016].

Robinson, B. (1995). Research and pragmatism in learner

support. In F. Lockwood (Ed.), Open and distance

learning today (pp. 221-231). London: Routledge.

Available at: http://www.c3l.uni-

oldenburg.de/cde/support/readings/robin95.pdf

[Accessed 13 Oct. 2016].

Shackelford, J. L., and Maxwell, M. (2012). Sense of

community in graduate online education: Contribution

of learner to learner interaction. The International

Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,

Vol. 13, No. 4. Available at:

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/13

39/2317 [Accessed 12 Nov. 2016].

Su, B., Bonk, et al. (2005). The importance of interaction

in web-based education: A program-level case study

of online MBA courses. Journal of Interactive Online

Learning, Volume 4, Number 1. Available at:

http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/4.1.1.pdf

[Accessed 25 Nov. 2016].

Tait, A. (2014). From place to virtual space: reconfiguring

student support for distance and e-learning in the

digital. Open Praxis, Student support services in open

and distance education, Vol. 6, Issue 1. Available at:

http://www.openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/artic

le/view/102/74 [Accessed 13 Nov. 2016].

A Case Study on the Importance of Peer Support for e-Learners

283

Zawacki-Richter, O., (2004). The importance of support in

online education. In: Brindley, J.E., Walti, C.,

Zawacki-Richter,O., (Eds.): Learner Support in Open,

Distance and Online Learning Environments. BIS-

Oldenburg: Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky. Available

at: https://www.uni-oldenburg.de/fileadmin/user_

upload/c3l/master/mde/download/asfvolume9_ebook.p

d [Accessed 15 Oct. 2016].

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

284