Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content

A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

Kay Berkling, Heiko Faller and Micha Piertzik

Cooperative State University of Baden W

¨

urttemberg, Erzberger Str. 121, Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords:

Games, Content, Design, Addiction, Education, Gamification.

Abstract:

Educational Games tend not to be designed by game engineers. They usually do not compare either in graphics

or in addictiveness to small games that people have installed on their mobile devices. In order to understand

why people play today, a survey was conducted to determine players’ explicit and implicit knowledge about

motivators in addictive games. Based on the results of the questionnaire, we studied demographic preferences

and commonalities in order to develop a recipe for the design that fits the general current market. An anti-

pattern was a by-product of this process. Both are then applied towards an analysis of existing games and the

design of a new one.

1 INTRODUCTION

Playing games can be addictive and fun. In contrast,

learning in the official context of education is often

stressful or perceived as a duty (Few, if any, stud-

ies look at the academic stress caused by educational

methods in schools today). Rare are the students who

cannot wait to get up in the morning to continue their

learning from last night, more frequent in first grade

than the later years. To improve the learning ex-

perience, researchers and educators have introduced

games into the classroom in different ways: By using

existing games in class or adding gamification me-

chanics to educational content. Due to the large num-

ber of publications in this area, we focus on literature

overview papers to establish the current status-quo in

this field of study.

1.1 Gamification

Gamification pertains to the analysis of mechanics

that make games fun and then applying these to situ-

ations outside of gaming in order to recreate the feel-

ing of fun or addiction to new applications such as

learning or marketing or the solving of mundane tasks

(rephrased from Oxford Dictionary).

According to (de Sousa Borges et al., 2014), there

have been a number of papers on various topics re-

lating to gamification in education. Very few, how-

ever, deal with actual game design for experience, so-

lution proposal, and validation with respect to master-

ing skills.

Dicheva (Dicheva et al., 2015) lists the papers that

have studied various features in gamification usage

for education. The most frequently studied mechan-

ics in order of popularity are: ’Status’, ’Social En-

gagement’, ’Freedom of Choice’, ’Freedom to Fail’,

’Rapid Feedback’ and ’Goals and Challenges’. Re-

searchers have studied gamification of educational

material and shown that there is a strong interest in

using game mechanics for education.

We believe that there remains a significant gap in

actually designing and validating the use of games

with academic content, going beyond gamification.

1.2 Games

Game-based learning (GBL) builds on existing

games, such as Civilizations, and re-uses it for an ed-

ucational purpose, like economics or history (Squire,

2006; Wiggins, 2016). Games are only starting to

make a very slow move into schools (Dickey, 2013;

Salen, 2011). The idea of using games in education

is sometimes treated differently in the literature and

called Educational Games or Serious Games (for ex-

ample, (Vaz de Carvalho et al., 2016)). These are

designed specifically with academic content in mind.

For the purpose of this paper, we prefer not to distin-

guish between games and serious games (this is not

unusual and seems to agree with the findings in the lit-

erature overview on the subject (Boyle et al., 2016)).

According to Merriam Webster, a game is defined as:

Berkling, K., Faller, H. and Piertzik, M.

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof.

DOI: 10.5220/0006281800250036

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 25-36

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

25

a) A form of competitive activity or sport played ac-

cording to rules. b) An activity that one engages in

for amusement. c) (adj) eager or willing to do some-

thing new or challenging. In this sense, there is no

need to give a special name to a game that has aca-

demic content. The key is instead on how the content

is designed as a game (for example pure game de-

sign (Egenfeldt-Nielsen et al., 2016), and it’s effect

on children’s learning outcome (Suarez Caraballo,

2014) and (Berkling et al., 2015)).

1.3 Extrinsic vs Intrinsic

The difference between extrinsic and intrinsic motiva-

tion has been sufficiently described (Ryan and Deci,

2000). The negative effects of extrinsic motivators on

intrinsic motivation and performance have been dis-

cussed repeatedly. Lately, Hanus (Hanus and Fox,

2015) has shown the effects of gamification in the

classroom in a longitudinal study:

• ”Over time, gamified students were less moti-

vated, empowered, and satisfied.

• Gamified course negatively affected final exam

grades through intrinsic motivation.

• Gamified systems strongly featuring rewards may

have negative effects.”

With ”Educational” Games and gamification we of-

ten obtain, as a result, exactly this sort of extrinsic

motivation by providing unrelated rewards. In con-

trast, popular games themselves seem to tend more

towards the intrinsic motivation and working with the

provided content to learn something. In this paper

we would like to contribute towards moving educa-

tion into the direction of understanding how to design

and use games with academic content.

It is known that content design is an integral part

of a good game and there is no reason that it cannot

contain the same information that would be studied in

an educational setting.

1.4 Demographic Dependence

Using game mechanics to design an addictive educa-

tional experience has been studied in detail. It is well

known that personas, typical user profiles of a known

demographic, are necessary for good design. Koivisto

and Hamari (Koivisto and Hamari, 2014) have shown

that age and gender play a major role when design-

ing gamification mechanics for their respective demo-

graphics. The work presented here incorporates de-

mographics but looks at common themes across de-

mographics for general audiences in education.

1.5 Relationship between Education

and Games

Vallerand (Vallerand et al., 1986) explains in a very

valuable summary the key to seeing education as a

game: It is important to identify the intrinsic rewards

relative to the culture and build game-like interactions

on top of these by focusing on mechanics like ”Free-

dom to Fail, Rapid Feedback, Progression and Story-

telling” - note that these overlap with those studied in

the gamification literature (Section 1.1). Stott (Stott

and Neustaedter, 2013) then makes the connection

with existing terminology in education. ”The Free-

dom to Fail” is analogous to formative assessment us-

ing ”Rapid Feedback”, ”Progression” relates to scaf-

folded learning and ”Storytelling” is equally recog-

nized as a powerful tool in the classroom.

What we can learn about the current culture of

games and what engages our time in gaming? Subject

of this paper is a more detailed recipe-like mapping

between these two areas.

1.6 Current Cultural Framework

This paper presents an update of the analysis of a list

of games as a function of their demographics. Look-

ing at the most popular games, a framework of fea-

tures (motivation factors) is developed. This frame-

work forms the basis for a survey of over 800 people

across different age ranges. With the newly gained

knowledge about gamers, we proceed to formulate a

recipe and an anti-pattern as a by-product. This in

turn is used to analyze a finished educational game

that has been released in the market and to show how

these steps generalize to a second game design.

This paper contributes to the general knowledge

in this area by providing an updated analysis on why

gamers play today. A survey is designed to find out

more about players in indirect and direct ways and

use this information to create a recipe for designing

games that happen to have academic content.

Section 2 explains the framework that was de-

veloped through detailed study of 27 popular games.

Based on this framework, a survey (see Appendix A2)

of over 800 participants was conducted and the results

are described in more detail in Section 3. Section 4

discusses what not to do in a game design and an-

alyzes the current situation in standard schools and

Universities. Since there is room for improvement in

the ’game of learning’, a subsequent step writes up

a recipe for game design with educational content in

Section 5. Given the recipe, an existing, successful

(with respect to skills improvement and fun) educa-

tional game is analyzed (Section 5.1) and a new game

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

26

designed (Section 5.2). Finally, Section 6 summarizes

and refers to future work.

2 ANALYSIS OF GAMES

A list of popular games from Google Play Store charts

and from subjective Experience of Bachelor students

is compiled. This list forms the basis of the question-

naire to analyze these games with respect to their fea-

tures in relation to the demographics of the players.

Four main categories of distinguishing features

evolved out of an iterative analysis of the games list

(see Appendix A1 for a comprehensive listing and

usage statistics): Game-mode, Motivation, Emotion,

Simplicity and other features not categorized. These

are each explained below (with examples):

2.1 Game Mode

Games can be distinguished by game mode. These

usually fall into one of these categories:

• One-level/infinity (Pineapple Pen, Piano Tiles)

• Level (Candy Crush, Angry Birds)

• Story (Clash of Clans)

2.2 Motivation

Motivation for games are simple game mechanics that

create extrinsic motivation such as listed below. We

distinguish between rewards and currency, that serves

as a mechanism to acquire new tools to help the player

progress. Goals define specific ”work” that has to be

accomplished irrespective of levels. Come-back mo-

tivations are types of appointments. High-score is a

form of competition with self or others and a progress

bar shows the path towards a goal or level.

• Rewards (Cut the Rope)

• ”Currency” (Subway)

• Goals (Angry Birds)

• Come back motivations (FIFA, Block Hexa Puz-

zle)

• Confrontation with high-score (Pineapple Pen,

Flappy Bird)

• Progress bar (Clash of Clans, Temple Run)

2.3 Emotion

A major factor in games are emotions that can be sup-

ported with emotional faces, sound or graphics. Fur-

thermore, fun, humor and spectacular death can sup-

port the creation of strong emotions for the player.

• Faces (Pineapple Pen, Pou)

• Sound-FX (all)

• Emotional Music (not for 2048)

• Humor (Angry Birds)

• Fun Death (Temple Run)

2.4 Simplicity

Simplification is important for on-boarding and ease

of movement across levels of difficulty. It should be

easy to start and proceed. The menu has to be quick,

direct and easy to understand:

• Fast proceeding (not Temple Run)

• Fast start (not Clash of Clans)

• Simple menu (Pou, Candy Crush)

2.5 Other

Other factors that do not fit into the above categories

have been determined as important aspects of a num-

ber of games that are currently popular: Their relation

to reality, patterns that are learned to improve perfor-

mance, social behavior (like feeding the animals in a

friends’ zoo) or competitions with self or others.

• Relation to reality (FIFA)

• Patterns (Roll the Ball)

• Social (Pou)

• Competitive (Flappy Bird)

Appendix A1 lists the games and gives detailed

analysis of these factors.

3 SURVEY: DESIGN AND

RESULTS

In order to gain a deeper understanding of how we can

use games in education and generalize their design

across populations, a current survey was conducted.

The survey builds on the features that we have defined

in the previous section.

3.1 Survey Construction

The survey includes three sections (see Appendix

A2).

• Demographic data

• Gaming Habits

• Games Installed and general Motivators

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

27

• Favorite Game and specific Motivators

• Emotions and their initiators

The evaluation of the survey should increase insight

into the motivators based on three methods of eliciting

information:

1. Installed games indicate interests indirectly

though framework,

2. Explicit motivation to play a favorite game, and

3. Indirect indicators of motivators that create fa-

vorite emotion as reason for playing.

These three insights allow us to understand how

games can be designed with academic content.

3.2 Demographics of Participants

The survey, using Google forms, was announced via

facebook games website and through university net-

works as well as employers. The result is a healthy

mix of people from industry and university, as well as

a good spread across age groups and gender. Figure 1

depicts an overview of the population that answered

the survey. In total 893 people responded to the sur-

vey within two weeks of posting it. Table 1 gives the

number of people who took the survey and fall into

each of the four categories of interest to us.

Figure 1: Survey Demographics.

Table 1: Participant numbers by Male/Female and Age

bracket (< 23 vs. > 31).

Subgroups < 23 > 31

Male 173 347

Female 107 145

Table 2: Significance in differences between subgroups

by % of chance that the two querried groups will differ

in their reponse. (YM, YF, OM, OF = Younger/Older

Male/Female).

Goals

Rewards

Competition

Friends

Emotions

YF vs. OF 0,47 0,32 0,19 0,50 0,28

YM vs. OM 0,99 0,73 0,61 0,75 0,99

YF vs. YM 0,84 0,37 0,99 0,84 0,96

OF vs. OM 0,02 0,08 0,89 0,74 0,22

3.3 Results of Motivators in Favorite

Game

Specific questions regarding motivators were asked

with the favorite game in mind. In particular distin-

guishing features of games were queried: Goals, Re-

wards, Competition, Friends, and Emotions. These

points are compared across the four above defined

demographic groups. With the likert skale from 1-

6 (1=not at all and 6=very much), groups 1-3 and

groups 5-6 are joined. The values in Table 2 represent

the chance

1

that the resulting two queried subgroups

respond differently to each motivator.

It shows that competition is of different impor-

tance for male than female, regardless of age. Goals

and Emotions have different importance for younger

vs. older males, Emotions differing also between

male and female when young. Regarding Goals and

Rewards male and female have assimilated with age.

Figures 2 and 3 show the difference between the

% of females minus % of males who selected a par-

ticular rating for a category. (Similar graphics can

be seen for the other two comparisons in Figures 5

and 4.) A higher positive bar shows preference by fe-

male or older demographic when compared to male or

younger demographic. When there is a large change

from ”very little” on the likert scale to ”very strong”

then it can be seen that there is a large difference be-

tween the two groups. For example, older males pay

little attention to emotion, while younger males feel

very strongly about this motivator. Younger females

differ most strongly in competition when compared

to young male. Changes from young to older females

are not so pronounced. Changes between older male

and females are also less pronounced, except for the

competition factor.

In order to understand more closely, which emo-

tions are important in playing and how these are cre-

1

This calculation is based on N-1 Chi-Square test as rec-

ommended by (Campbell, 2007), using the 2-tailed p-value.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

28

Figure 2: Difference between younger males and females.

Figure 3: Difference between older males and females.

ated, one question relates to this regarding the specific

favorite game. Namely, which emotion is produced

by the game and how this emotion is established. An

interesting commonality is found here. Either gen-

der and age group plays for fun and enjoyment. And

each group has mostly minor differences in opinion

on how this fun factor is established. Namely excel-

lent graphics, the ability to improve oneself and the

increasing difficulty. The astonishingly similar distri-

bution is shown in Figure 6. These results corrobo-

rates findings from game design and Psychology (for

example, (Koster, 2014; Bianco et al., 2003)).

3.4 Results of Motivators in General

Based on the installed games on people’s devices, a

profile can be established that compares a tendency of

games and their features that are preferred by gender

or age group. (More analysis can of course be done on

various other parameters.) Equation 1 defines how the

representative number for each group and each fea-

ture (see appendix) was calculated. The cross product

between the number of people within the subgroup

Figure 4: Difference between older and younger males.

Figure 5: Difference between oder and younger females.

who have installed a particular game on their com-

puter with the feature vector across these same games

is normalized as given in Equation 1. This value rep-

resents a preference for a given motivator within the

selected group of respondants to the survey.

Value

(Subgroup∧Feature)

∑

games

i

(X

i

Y

i

)

∑

games

i

X

i

∑

games

i

Y

i

, (1)

where X is the vector of persons in a particular

subgroup who have this game installed given the sub-

group and Y is the analysis vector for a particular

game feature across all games. This Vector has a 1

if the feature exists and a 0 if the feature does not ex-

ist. (The feature vectors are referenced in Appendix

A1)

The resulting values can then be compared across

subgroups as shown in Figures 7 and 8. Looking at

these, we can determine the following trends (among

others):

• Differences between females and males get more

pronounced as they get older.

• Males like faces, humor and fun death.

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

29

Figure 6: Commonalities on most important emotion and

how this emotion is created.

• Older people need more goals.

• Females like a come-back incentive.

• Females tend to be more interested in levels than

males.This is less pronounced in younger ages.

• Some differences between gender are more pro-

nounced in the older demographic.

• Figure 9 shows items that are most sensitive to

gender specific demographics. Among these are

also levels, rewards and competition that will be

discussed in more detail later.

Figure 7: Values (Equation 1) for female demographics

sorted by younger females (implicit feature preference).

Based on the features preferences across the

games we can establish that there are indeed differ-

ences when looking across all the various features that

games have. While this information shows implic-

itly which features are preferred through the games

that are installed, it is not guaranteed that all installed

games become favorites. So, they do not necessar-

ily represent a true picture of favorite games choices.

However, they may serve as an indicator given the

Figure 8: Values (Equation 1) for male demographics,

sorted by younger males. (implicit feature preference).

Figure 9: Selected motivators showing differences in gender

for younger and older demographic groups. The younger

demographic tends to have less pronounced differences.

large set of data. The next step is to compare features

specific to the favorite game.

3.5 Results of Direct Questions about

General Motivators

Questions, looking more specifically and detailed at

the motivators of Levels, Rewards and Competition,

were asked. While they seem to be favored in dif-

ferent ways by demographic groups, a more detailed

examination shows commonalities.

Figure 10 depicts the relative importance of levels

in games for both males and females in general and

in their favorite game. All demographics, whether in

general or for their favorite game, favor levels.

Figure 11 depicts preferences for several different

types of competitions that can be used in games. It

shows that certain types of competition are more in-

teresting than others. While there are gender differ-

ences, there is some agreement across demograph-

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

30

ics that competition with self is more preferred than

global competition.

Figure 12 shows that there are different types of

rewards. In general rewards may not be important to

players. However, looking in more detail at different

types of rewards, there are differences. If the reward

pertains to gaining more power or skills in the game,

they are of interest to a larger number of people than

simple rewards that do not enable the player. This

finding holds true across all demographics.

Figure 10: How important are levels?

Figure 11: Which types of Competition are Prefered?

3.6 Summary and Conclusion of Survey

Results

Looking at implicit and explicit preferences in mo-

tivators, we have shown differences in demographic

subgroups. But more importantly, we have gained

insights into commonalities that are necessary to de-

sign a game for the general public, regarding motiva-

tors for academic content learning. The survey shows

how levels, competition and rewards have to be care-

fully used within a good design. With the gained

Figure 12: How important are Rewards?

knowledge, we can define anti-patterns, how not to

use a game in the classroom or how to design a game

with academic content. Similarly, we can define good

practice on how to present content to users. With

these patterns, we analyze existing games and create

new designs. People enjoy playing for fun. This fun

is created with three major points regardless of demo-

graphic: Learning is fun if it increases without bound-

aries in difficulty. As long as the graphics are good.

The survey has re-confirmed that educational content

is even a necessity for a fun game.

4 GAME DESIGN:

ANTI-PATTERN

Game design can be done badly and it is of interest to

define an anti-pattern, a pattern for bad design (when

designed for the general crowd) and is deducible from

the survey results.

4.1 Anti-Pattern

• Single Level (fits fewer demographics)

• Bad Graphics (Crowded, low quality (unless

funny), unrelated to content): For example, too

many icons, graphic elements and texts.

• No rewards or unrelated rewards (that do not con-

tribute directly to increased skill)

• Little self-awareness of skill increase

• Too complex on-boarding or advancement

• Long units of play necessary

• No view of own high-score to compete with

• No replay of level - ie. no chance to improve

• Too much material at the same time (unleveled)

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

31

• Path to restrictive (no choices)

Levels can be designed badly as follows:

• Few levels

• Too many repetitions, no new elements

• No individual speed

• Competition with others

• No improvement in finished levels possible

4.2 Analysis of Generic Educational

System

Analyzing the generic learning environments, that

still pervade most of the education system, in terms

of this anti-pattern one can see some design issues

from the point of view of enjoying learning in schools

or universities today. While schools have levels (first

grade, second grade, ...), there is no individual speed.

In fact, there often is competition with others and af-

ter a level is finished, no improvement is possible. A

bad grade not only can not be improved, but can per-

manently hold students back in future levels.

While grades can be seen as rewards (for those

who do well), they do not represent new tools for

solving more complex problem sets. They may not

even reflect skills accurately by themselves (Schuler

et al., 1990; Trapmann et al., 2007b; Trapmann et al.,

2007a). Students tend to have little knowledge of their

own skills since there is no progress bar during the

course of one class (with respect to skills - there are

progress bars in terms of time and exam dates). The

learning path is also very restricted with few electives

and no control over the speed at which the content

will be mastered.

Furthermore, the on-boarding process and further

progression is not always easy, ”I have no time to

learn, I need to prepare for the exam next week” -

is a typical anti-pattern in the game of learning.

Finally, the units of the game are often quite long,

if we can measure them by time between exams. In

school, there are weeks, at University there can be

whole semesters between exams and level-unlocks.

The number of levels with respect to the content are

additionally too few. So learning, in our society has

not yet matched the pattern of good game design for

the general population. It remains to be proven quan-

titatively whether good game design in education im-

proves the skills outcome.

5 GAME DESIGN: RECIPE

Based on the findings of the survey of 2016 on how

games are played explicitly as well as implicitly, one

can establish a checklist of important design elements

when building a game around academic content for

the general public, that is, they hold mostly true across

demographics.

In general, the following points are absolutely es-

sential and can not be bypassed:

• Graphics (Consistent and Simple)

• Rewards (Must relate to capabilities)

• Increasing Difficulty

• Increased Knowledge

• Easy to start and stop playing

• Competition with Self

• Leave out everything else

Design steps should include the usage of levels in the

following way:

• Many Levels (Consistent and Simple)

• Frequent new elements

• Levels can be infinite (level-based improvements)

• Don’t use single level

5.1 Analysis: Phontasia

Phontasia is a game that has educational content

and is on the market (Berkling and Pflaumer, 2014;

Berkling et al., 2015). It has been successfully de-

ployed in schools and has demonstrated an increase in

skill level for the academic content presented within

the game. The content of the game relates to phonics

for German orthography and allows children to pro-

ceed from simple patterns to more complex patterns

in the same way phonics does that for English. The

game is set up as a magician’s lab where the player

mixes potions of letters into words. The potions be-

come increasingly complex. Observation of game use

has shown that it is highly addictive in addition to im-

proving the skills. In fact, becoming expert at the skill

is the central learning goal that children are pursuing

because the skill is gained and the new level of diffi-

culty is the reward, as new potitions become available.

• Graphics (Consistent and Simple)

Graphics are beautiful and supported with sounds

that match the underlying theme and the task.

• Rewards (Must relate to capabilities)

There are negative rewards, a heart can be lost

three times to catapult players back to the start

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

32

(similar to the game of Ludo). The reward is in-

direct in that correctness of the work results in the

ability to reach the next level. The next level has a

larger number of potions that come with increase

in power to work with, resulting in new patterns

to discover.

• Increasing Difficulty

Each level offers new opportunities to explore and

with that new difficulties and new potions to mix

in. Letters in new positions are rewards and gifts

that give new power. With this power comes diffi-

culty of words to be spelled.

• Increased Knowledge

The students learn to spell words that they had

been previously denied because the necessary po-

tions were not yet acquired.

• Easy to start and stop playing

It is easy to start and stop playing at any time.

Stopping in the middle of the most successful

streak is even a good idea because kids cannot

wait to come back and play again to prove, they

can reach the next level.

• Competition with Self

There is intense competition with self in order to

reach the next level, without losing a heart, faster

than last time, improving automaticity and profi-

ciency in the player (learner).

• Leave out everything else

Nothing else happens in this game except word

spelling and the sounds of the magic mix.

Design steps should include the usage of levels in the

following way:

• Many Levels (Consistent and Simple)

There are 12 levels, a lot to a second grader. Each

level adds only one small additional potion.

• Frequent new elements

Each level offers new elements and challenges.

They look and feel like rewards because the kids

can finally spell new words that they had been

waiting for and prevented previously (Mostly due

to orthographic misconceptions by the player that

are now being learned correctly).

• Levels can be infinite (level-based improvements)

Each level can be played again. In fact, many chil-

dren go back to replay the lower levels because

they enjoy feeling comfortable with already mas-

tered skills.

5.2 Design: Drum Stix

Drum Stix is a game designed to teach rhythm. It has

gone through three iterations of design, successively

using more of the information gained from the survey

and its analysis.

5.2.1 First Design

The original game design consisted of a single-level

game containing small mini-games that were trig-

gered when certain levels were reached in the game.

5.2.2 Revision

According to the survey, levels are important to a

larger demographic. The new design contains a strat-

egy game (build up a village) as basis with levels in

form of missions (or goals) to be achieved to level

up. There are still mini-games as in the original de-

sign but the levels are now more visible to the stu-

dent. There is a dependency between missions and

rewards of currency type (this currency can be used

to buy material for the village). A well-build village

improves the depth of the missions until the game be-

comes increasingly complex. This elaborate reward

system bypasses the original content of rhythm learn-

ing. The survey strongly indicated little interest in

such rewards that are not content or learning progress

related.

5.2.3 Final Version

The game should have easy on-boarding and progres-

sion with constant improvement. Therefore, the com-

plex original design was rejected for a simplified level

design. Maximally simple and dedicated only to the

content in question, the app is opened and a play but-

ton leads directly to the drums, which are the center of

learning. In the first level, 2 drums are visible: ’Kick’

and ’Snare’.

Each level consists of one task. A song is played

in the background. Each drum is marked with a color

and number. The progress-bar (for the song) indicates

which drum should be played (Karaoke style). Miss-

ing a drum-beat results in a mark-down. Correct per-

formance results in a mark-up of points. As the player

repeats this rhythm, the karaoke support is removed.

The level ends with the first mistake the user commits.

As the levels ends, the user is shown his own current

and his highest score. Played levels can be repeated

any time, even as new levels open up.

Gamers can individually adjust the drums accord-

ing to their needs. They can be placed differently or

new drums can be purchased with the collected coins.

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

33

In buying a new drum, the next level starts. Any open

level can be played with the purchased drums. With

the increasing number of drums, the game becomes

more difficult. More coins can be won and bigger,

additional instruments bought. Rhythms are growing

faster and more complex. While the first purchase is

easy to obtain, further advancement is based on im-

proved skill. There are a large number of levels and

care will be taken to create fun graphics.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

We have aligned current cultural motivators for the

general audience with a design recipe and an anti-

pattern. Based on the responses of a large number of

participants, it was shown that different demographics

may differ in certain aspects of game features; there

are nonetheless several very important commonali-

ties. Namely, what constitutes fun, that rewards need

to make sense to improve learning and that competi-

tion is relevant mostly with respect to self. We have

shown how the use of levels is constructive for users.

By providing a recipe and showing how this is applied

during design, a generalizable contribution to the field

of study has been provided. An anti-pattern furthers

understanding of mistakes to avoid during design.

While there are studies providing recipes in gamifi-

cation (Nicholson, 2015) or blended learning (Naaji

et al., 2015), these are not based on large numbers of

participants, nor are they focusing on generic vs. spe-

cific motivators as a function of demographics. The

elaboration of current literature in the field of games

in education, the analysis of responses from gamers

and the ensuing detailed analysis of game design and

its generalization has led the authors once more to

believe that game design is necessary to put the en-

joyment back into learning while improving learner

skills. Regarding future work, there are at least two

areas of work. Given the learning from the survey, a

new design of the survey and re-run would be impor-

tant. In order to show the relevance of game design in

academic content, there must be more focus on mea-

suring learning impact. There are too few studies ac-

cording to the literature (Boyle et al., 2016), for ex-

ample (Novak et al., 2016). Even if there are smaller

studies, these are often not general enough because

they are generated in a specific environment without

quantitatively motivated framework nor performed on

a large number of participants. More research effort

is needed regarding generalizability and outcomes as-

sessment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A big thank you goes to the people who participated

in the survey in order to help understand the current

motivation behind playing games.

REFERENCES

Berkling, K. and Pflaumer, N. (2014). Phontasia - a phon-

ics trainer for German spelling in primary education

Singapore, September 19, 2014. In Berkling, K., Giu-

liani, D., and Potamianos, A., editors, The 4st Work-

shop on Child, Computer and Interaction, WOCCI

2014, Singapore, September 19, 2014, pages 33–38.

ISCA.

Berkling, K., Pflaumer, N., and Lavalley, R. (2015). Ger-

man phonics game using speech synthesis - a longi-

tudinal study about the effect on orthography skills

Education, SLaTE 2015, Leipzig, Germany, Septem-

ber 4-5, 2015. In Workshop on Speech and Language

Technology in Education, volume 6 of SLaTE, pages

167–172. ISCA(ISCA) International Speech Commu-

nication Association.

Bianco, A. T., Higgins, E. T., and Klem, A. (2003). How

fun/importance fit affects performance: relating im-

plicit theories to instructions. Personality & social

psychology bulletin, 29(9):1091–1103.

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J.,

Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., and Pereira,

J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature re-

view of empirical evidence of the impacts and out-

comes of computer games and serious games. Com-

puters & Education, 94:178–192.

Campbell, I. (2007). Chi-squared and Fisher-Irwin tests

of two-by-two tables with small sample recommen-

dations. Statistics in medicine, 26(19):3661–3675.

de Sousa Borges, S., Durelli, V. H. S., Reis, H. M., and

Isotani, S. (2014). A systematic mapping on gamifica-

tion applied to education. In Cho, Y., Shin, S. Y., Kim,

S., Hung, C.-C., and Hong, J., editors, the 29th Annual

ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, pages 216–

222.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., and Angelova, G. (2015).

Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping

Study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,

18(3):75–88.

Dickey, M. D. (2013). K-12 teachers encounter digi-

tal games: A qualitative investigation of teachers’

perceptions of the potential of digital games for K-

12 education. Interactive Learning Environments,

23(4):485–495.

Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S., Smith, J. H., and Tosca, S. P. (2016).

Understanding video games: The essential introduc-

tion. Routledge, New York and London, third edition

edition.

Hanus, M. D. and Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of

gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study

on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfac-

tion, effort, and academic performance. Computers

& Education, 80:152–161.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

34

Koivisto, J. and Hamari, J. (2014). Demographic differ-

ences in perceived benefits from gamification. Com-

puters in Human Behavior, 35:179–188.

Koster, R. (2014). A theory of fun for game design. O’Reilly

Media Inc, Sebastopol, CA, second edition edition.

Naaji, A., Mustea, A., Holotescu, C., and Herman, C.

(2015). How to Mix the Ingredients for a Blended

Course Recipe. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial

Intelligence and Neuroscience, 6(1-2):106–116.

Nicholson, S. (2015). A RECIPE for Meaningful Gam-

ification. In Reiners, T. and Wood, L. C., editors,

Gamification in Education and Business, pages 1–20.

Springer International Publishing.

Novak, E., Johnson, T. E., Tenenbaum, G., and Shute, V. J.

(2016). Effects of an instructional gaming character-

istic on learning effectiveness, efficiency, and engage-

ment: Using a storyline for teaching basic statistical

skills. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(3):523–

538.

Ryan and Deci (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations:

Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contempo-

rary educational psychology, 25(1):54–67.

Salen, K. (2011). Quest to learn: Developing the school for

digital kids. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur

Foundation reports on digital media and learning. MIT

Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Schuler, H., Funke, U., and Baron-Boldt, J. (1990). Pre-

dictive Validity of School Grades -A Meta-analysis.

Applied Psychology, 39(1):89–103.

Squire, K. (2006). From Content to Context: Videogames

as Designed Experience. Educational Researcher,

35(8):19–29.

Stott, A. and Neustaedter, C. (2013). Analysis of gamifica-

tion in education. Surrey, BC, Canada, 8.

Suarez Caraballo, L. M. (01.01.2014). Using Online Math-

ematics Skills Games To Promote Automaticity. PhD

thesis, Cleveland State University.

Trapmann, S., Hell, B., Hirn, J.-O. W., and Schuler, H.

(2007a). Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between

the Big Five and Academic Success at University.

Zeitschrift f

¨

ur Psychologie / Journal of Psychology,

215(2):132–151.

Trapmann, S., Hell, B., Weigand, S., and Schuler, H.

(2007b). Die Validit

¨

at von Schulnoten zur Vorhersage

des Studienerfolgs - eine Metaanalyse 1Dieser Beitrag

entstand im Kontext des Projekts “Eignungsdiagnos-

tische Auswahl von Studierenden”, das im Rahmen

des Aktionsprogramms “StudierendenAuswahl” des

Stifterverbands f

¨

ur die Deutsche Wissenschaft und

der Landesstiftung Baden-W

¨

urttemberg durchgef

¨

uhrt

wird. Zeitschrift f

¨

ur P

¨

adagogische Psychologie,

21(1):11–27.

Vallerand, R. J., Gauvin, L. I., and Halliwell, W. R. (1986).

Negative Effects of Competition on Children’s Intrin-

sic Motivation. The Journal of Social Psychology,

126(5):649–656.

Vaz de Carvalho, C., Escudeiro, P., and Coelho, A., edi-

tors (2016). Serious Games, Interaction, and Sim-

ulation. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Com-

puter Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommu-

nications Engineering. Springer International Publish-

ing, Cham.

Wiggins, B. E. (2016). An Overview and Study on the Use

of Games, Simulations, and Gamification in Higher

Education. International Journal of Game-Based

Learning, 6(1):18–29.

Avoiding Failure in Modern Game Design with Academic Content - A Recipe, an Anti-Pattern and Applications Thereof

35

APPENDIX

A1. Games

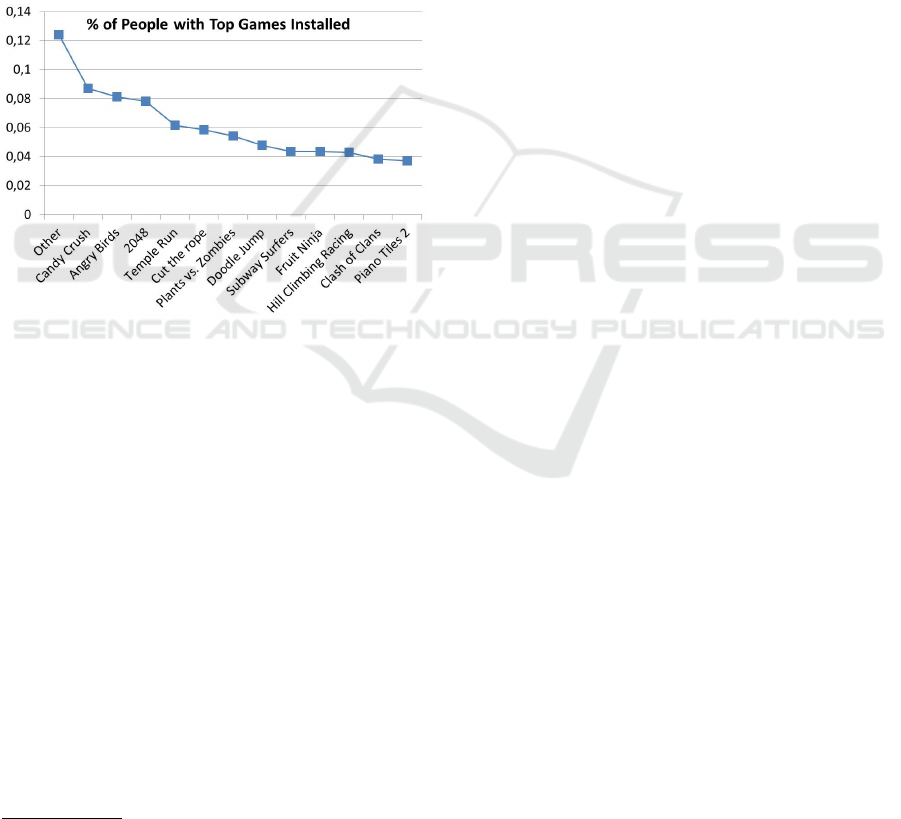

The list of games that are chosen for the study

is as follows: Figure 13 shows the distribution of

games as they are installed on devices.

FIFA, Pineapple Pen, Block! Hexa Puzzle, Pi-

ano Tiles 2, Rolling Sky, Subway Surfers, Clash of

Clans, Flippy Bottle Extreme, Color Switch, Roll the

Ball, Temple Run, Pou, Hill Climbing Racing, Candy

Crush, Angry Birds, Fruit Ninja, Geometry Dash, Cut

the rope, 2048, Doodle Jump, Plants vs. Zombies, Jet-

pack Joyride, Stack, Dumb ways to die, Flappy Bird,

Minesweeper, Tetris

Figure 13: Popularity of Games.

Figure 13 depicts the distribution of users that se-

lected this game as installed on their mobile device.

The games are analyzed by their features as discussed

in Section 2. The Table of features by game can be

found on the github project page

2

.

A2. Survey

The links to the survey and the analysis page

are online

3

.

6.1 Gameplay on Smartphones

6.1.1 Demographics

• Age (<13;14-18;19-23;24-30;31-50;>51)

• Gender

• Job/University/School form

2

https://github.com/heikofa/StudienarbeitWebanalyse

3

https://goo.gl/forms/qoLenhj9mhzeHoMR2

http://www.heiko-faller.de/studienarbeit

• Type of University (list)

6.1.2 Playhabits

• (mark one) How many times do you play (several

times a day, daily, several times a week, once a

week, rarely, never)

• (mark one) How long do you play (minutes, ¡ 30

minutes, longer)

• (check all) Where do you play? (home, commute,

at work/school)

6.1.3 Questions Regarding General Games

• (check all) What type of game do you like? (strat-

egy, level, single-level, other)

• (check all) Which competition motivates you?

(competition with self, with others, does not mo-

tivate, other)

• (mark one) How strongly are you motivated by

these types of rewards (not at all, very little, lit-

tle, medium, strongly, very strongly):

– Reward for daily play

– Rewards that are useful in the game

– Rewards that embellish

– Other

6.1.4 Which Games do You Have Installed?

• (check all ) see list of games above

• other

6.1.5 Favorite Game

• Which one

• (mark one) What level modus (single level, multi-

ple level, strategy, other)

• (mark one) How strongly are you motivated by

these types of rewards (doesnt exist, very little,

little, medium, strongly, very strongly)

– goals

– rewards

– competition

– friends

– emotions

• (check all) Which emotions do you have during

this game? (Fun, fear, stress, tension, nervous-

ness, frustration, other)

• (check all) Which motivators create this emotion?

(graphics, sound, humor, fatal death, open end

to improvement, competition, rewards, increasing

difficulty, clear path, other)

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

36