Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach

Uttam Kokil

and Sandra Scott

College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Kennesaw State University, Marietta campus, Kennesaw, GA 30060, U.S.A.

Keywords: Usability Testing, Think Aloud Protocol, Observational Method.

Abstract: The purpose of a school website is to provide pertinent information to parents and prospective site visitors. A

qualitative method was adopted to conduct a usability study to explore how parents interact with an

elementary school website in the USA. While the site yielded high ratings in terms of its visual appeal, the

usability test uncovered issues compromising its usefulness. Participants cited deficiencies in terms of poor

organization of information, and text labels not reflective of the contents, resulting in tedious navigation and

unsuccessful searches. Recommendations were made for site improvements with the goal to eliminate

usability issues, to make the site more efficient and effective for users.

1 INTRODUCTION

At times, website designers neglect to carry out a

website usability testing, even though it is an essential

process for ensuring that the site meets the needs of

the intended users. That often turns out to be a short-

sighted decision as unforeseen problems emerge and

users become frustrated. A cursory exploration of a

particular elementary school website revealed

possible usability issues that warranted testing, and so

a usability test was designed aiming to identify

specific problem areas through (i) observation of user

interaction with the website, (ii) think-aloud protocol

(iii) interview with the participants. Following the

findings, recommendations were made for

implementation to improve the website.

Based on the preliminary issues that were

observed, the following objectives were developed

for the test: (1) to assess how easily and successfully

users find information on the website, (2) to

determine how information retrieval relates to the

structure of the site, (3) to determine how finding

information relates to the organization of the content,

and (4) to get users’ perspectives on their overall

experience with the site. The following research

questions were formulated to focus on specific areas

contributing to the objectives of the study, as follows:

(i) Do navigation paths meet users’ expectations? (ii)

Is information organized in a logical manner (iii) Is it

easy to learn how to use the site? (iv)What kinds of

emotional reactions do users express while using the

site? (v) Does the appearance of the site make it easy

to use the website? (vi) What do users like about the

site? (vii) What do users dislike about the site?

The primary users of the school’s website are

parents who are seeking information about the school.

The site features internal information from the school,

as well as external information from the school

district administration. Piper (2012) views a school’s

website as an excellent medium for communication

between the school and the home. The author believes

that the website should facilitate active participation

in what goes on at the school—especially for

parents—and discusses a number of proactive ways

in which one school ensures this. This kind of

engagement through a school’s website must begin

with a site that caters to the needs of its users. This

study is focused on a more fundamental level of user

need regarding a school website—the ability to find

information. Its results will help to ascertain how well

the elementary school website functions as a point of

contact with the school for its primary users as it

relates to finding information with ease.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Usability can be evaluated using three major

constructs: apparent usability, perceived usability

and task performance (Gu et al., 2016). Apparent

usability is a user’s subjective judgment of ease of use

based on the visual appearance of a product.

Perceived usability is related to how users feel

designated by their subjective judgment of human-

Kokil U. and Scott S.

Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0006295500550064

In Proceedings of the 12th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2017), pages 55-64

ISBN: 978-989-758-229-5

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

55

product interaction. Performance is an objective

usability evaluation concerning the time it takes for a

user to complete specific tasks while using a system.

The twelve fundamental usability principles

concerning website evaluation are referred as

Nielsen’s heuristics (Nielsen, 1994). Studies on web

usability have been conducted from different angles,

notably learnability, consistency, satisfaction

(Nielsen, 1994), reliability and navigation (Egger et

al., 2003), interactivity (Lowry et al., 2006),

usefulness (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008). The usability

of websites is therefore defined by a number of

attributes listed above that provide experiential

meaning to users in the interaction with websites.

These attributes were useful in guiding the design of

the instruments for the usability test, and in indicating

necessary areas of focus.

In a study, Hartshorne et al. (2008), examined the

effectiveness of elementary school websites, cited

four functions of these sites, two of which are

considered in this study: providing an introduction to

the school itself, and providing access to other related

information—such as internal and external resources

for members of the school community. The authors

analyzed fifty elementary school websites, mainly in

the areas of content, structure and design. These areas

were detailed in a checklist aligned with factors in this

usability test. These include users’ impressions of the

homepage, aesthetics, navigation back to the

homepage, ease of moving around the site and ease of

finding information.

Spool, et al. (1997), after conducting usability

tests on nine websites (a mix of e-commerce,

corporate and other informational sites), found that

navigation issues often led to the failure of users to

find information. A site structure that users could not

follow intuitively was found to be one of the main

causes (p. 13). This seemed worthy of investigation,

and so tasks were designed in this study that would

test the ability of participants to successfully navigate

the site. Spool, et al., (1997) also found that a

website’s graphic design had no effect on the ability

of users to find information. In fact, of the sites they

tested, the one that was rated the best in terms of

usability had mostly text (p. 7). It has been shown that

aesthetically pleasing websites have led to positive

affect (Norman, 2004; Zhang and Li, 2005), user

satisfaction (Cyr et al., 2005), navigation (Battleson,

et al., 2001), fun and pleasure of usage (Creusen and

Snelders, 2002). Koutsabasis and Isitikopoulou

(2013) developed a method for evaluating the

aesthetics of websites in Human Computer

Interaction, but did not go as far as relating aesthetics

to navigation. Moshagen and Thielsch (2011) devised

the VisAWI instrument to measure perceived aesthetic

quality in websites given the importance of visual

aesthetic components play in digital products and

systems. Noting the differing opinions, and though

not intending to explore the technical details of

aesthetics, the opinions of users about the overall

appearance of the site—including whether it

enhanced the process of searching for information in

any way—was incorporated into the current usability

test.

In terms of methodology, the think-aloud protocol

and the concept of speech genre expounded by Boren

and Ramey (2000) were found to be very useful.

Speech communication in usability testing essentially

provides a refinement of the think-aloud protocol that

appears to enhance not only its practicality as a form

of human interaction, but, even more importantly, its

effectiveness.

An important aftermath of the process is

transcription of the audio recordings. Davidson

(2009) believed that selectivity and transcription go

hand in hand, and that this reality should be explained

as it relates to a study. Markle et al. (2011), in

referring to interviews, noted the inherent inadequacy

of transcription in capturing the emotion behind the

spoken word (p. 4), as well as the tedium of the task

(p. 3). The authors mentioned voice-recognition

software, which is supposed to work well with a

single voice (p.10), but such software was unlikely to

do justice to the long pauses and under-the-breath,

sometimes barely audible, utterances that were part of

the recordings in this study. It was therefore found

expedient to transcribe recordings of the think-aloud

sessions by typing them out. Bailey (2012), and Sauro

(2011), demonstrated that tracking test participants’

first clicks could yield valuable information in terms

of predicting their likelihood of success. This view

was also supported in the First Click Testing article at

www.usability.gov (n.d.). Hence, the tracking of first

clicks was incorporated into this current testing.

According to Pendell and Bowman (2012), five to

eight participants are usually required for an effective

usability test, but because of the unique requirements

of their test, they used twelve. Dickstein and Mills

(2000) felt that statistical significance could be

inferred from the results of eight to ten participants,

but acknowledged that after four or five users they

were able to tell if something was problematic. In

fact, Nielsen (2012) concluded that five users were

enough for an effective test. Ten participants were

used for this study. This number was considered ideal

to provide a reasonable body of data from which

trends, patterns, and results would be very clear for

purpose of analysis.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

56

3 METHOD

The procedures for data collection in this usability

test were:

Observation of users performing authentic

tasks.

Administration of pre- and post-test

questionnaires.

Think-aloud protocol.

Discussions with participants.

A qualitative approach was adopted because of

the exploratory nature of the study, especially useful

in observing users interacting with the website while

using the think-aloud protocol (Preece et al., 2015). A

convenience sample of ten participants was chosen

from among persons whose children were currently in

the school system or had passed through the school

system. A wide age range was targeted—18 to 60

years—to accommodate grandparents and others who

function as guardians. The generic term “parents” is

used throughout the study to refer to all. All

participants were female. Individual test was carried

out over an eleven-day period.

There were two questionnaires: a pre-test

questionnaire and a post-test questionnaire. Both sets

of questionnaires were piloted with three persons.

The pre-test questionnaire was designed to assess the

participants’ level of comfort with the Internet, get

their initial impression of the website, and provide

some demographic information. The proficiency of

the participants with the Internet varied, and while it

was desirable to have participants who had the

capability to interact comfortably with the interface,

it was also beneficial to have at least one Least

Competent User (LCU) to represent the other end of

the spectrum.

The post-test questionnaire was designed to

capture the experience with the tasks, likes and

dislikes regarding the website, and suggestions for

improvement. The recorded think-aloud protocol,

supplemented by notes from observations and post-

test discussions, provided valuable data that might not

have been included while the participants filled the

questionnaires.

In order to organize the data, an Excel workbook

was created with four sheets as follows: (1) Pre-

questionnaire, (2) Post-questionnaire Part A, (3) Post-

questionnaire Part B, (4) Task analysis. Part A of the

post-test questionnaire consisted of closed-ended

questions using the Likert scale for responses, while

Part B consisted of open-ended questions. Responses

from the questionnaires were logged in text format,

and, where applicable, tallied. Thematic analysis was

done on the answers to the open-ended questions on

the post-test questionnaire Part B to arrive at codes

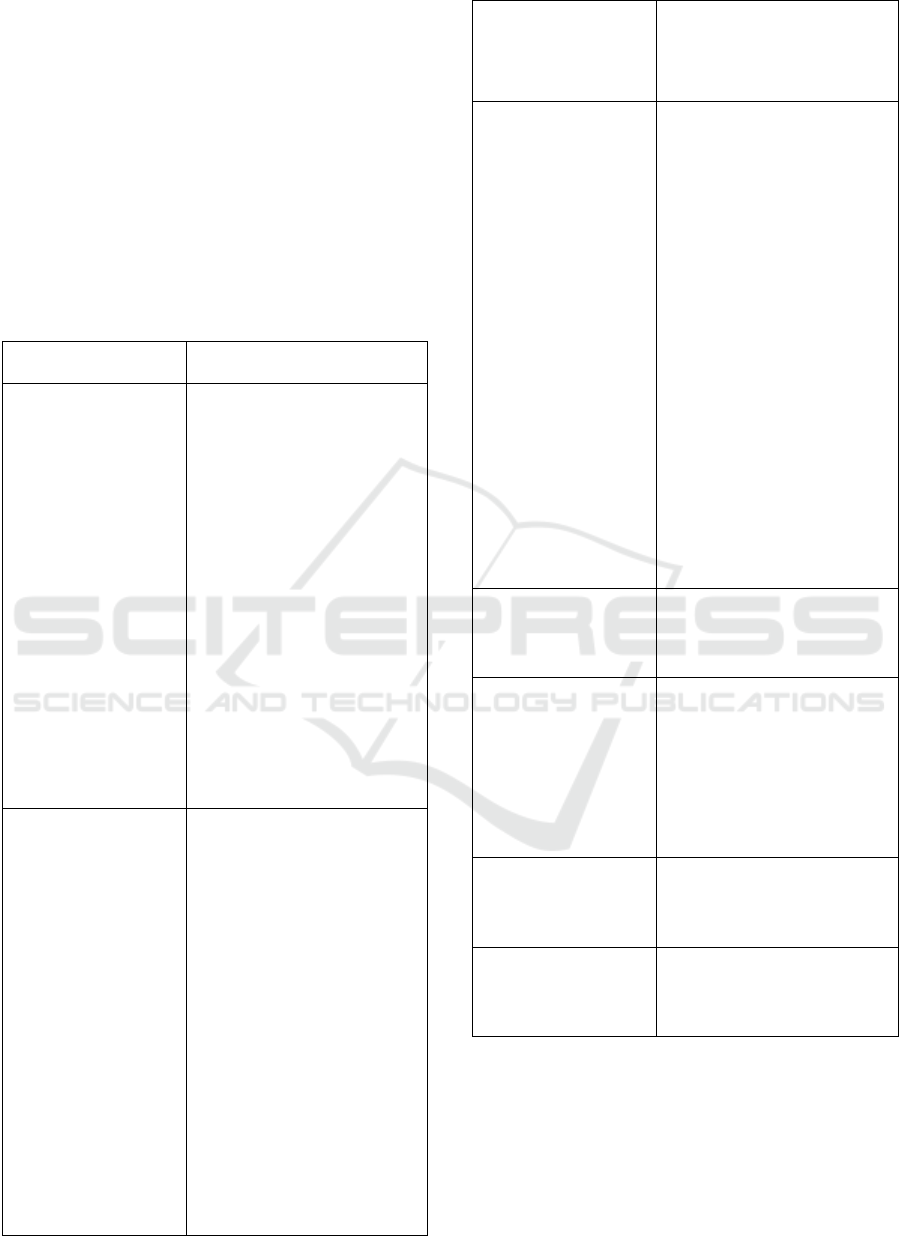

that related to the research questions. Figure 1 shows

the analysis of two comments that were made in

response to the question: What did you dislike about

the site?

Figure 1: Emergence of Themes.

Themes were derived by two levels of analysis.

Initial codes were generated from an overview of the

data, then as the data were studied in more details,

further aspects of a comment became evident, which

warranted separated codes. The frequency with which

these codes/themes occurred was then checked to

identify patterns. For example, in response to what

participants liked about the website, nine out of ten

participants, or seventeen out of a total of twenty-four

points that were made, mentioned appearance.

Location of information was the highest occurring

theme in response to what participants disliked. The

pre-test questionnaire did not have any open-ended

questions, so answers were collated/tallied for each

question, or selected answers logged for each person.

Transcription of the think-aloud recordings was

concentrated on test participants’ talk about the tabs

and links on which they clicked, so that their routes

in performing a search task could be re-created for

purpose of analysis. In transcription, those points

were put in bold lettering. As Markle, et al. (2011)

noted, it is difficult for transcription to capture the

emotions expressed by participants. This is inevitably

the case when they are not verbalized. Observer notes

proved to be a very good backup for this as body

language and expressions were noted. Transcription

synchronized well with the observer’s handwritten

notes of critical search paths.

Qualitative data was of paramount importance in

this study because, as will be shown in the Discussion

section, quantitative data, in the form of time on tasks,

for example, provided rather limited information to

examine the research questions adequately.

Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach

57

3 ANALYSIS

This section explains how the data collected were

applied to each research question. Questionnaires and

tasks had been carefully designed to align with the

research questions, so the data collected could be

related directly to these questions. Table 1 below

outlines the specific data used to answer each

question. Data from the sources indicated were

combined to give a complete picture for each question

and ensure that the overarching objectives of the

study were addressed.

Table 1: Applying data to research questions.

QUESTIONS

DATA AS INDICATOR

Do navigation paths

meet users’

expectations?

Subjective data

Response to post

questionnaire statements:

“Navigation paths met my

expectations”, “I knew where

I was in relation to the

homepage at all times”, “I

could retrace my paths

easily”.

Performance data

Homepage tab was selected to

start each task, number of

tabs/links clicked during

search.

Other

“Think-aloud” comments and

observations”

Is information

organized in a logical

manner?

Subjective data

Response to post-

questionnaire statements:

“information was presented in

a way that made sense”,

“website is designed to meet

users’ needs”, “I think the site

is well laid out”. References

to location of information in

response to post-test

questionnaire question “what

did you dislike about the site”,

and to suggestions for

improvement. Number of

participants that mentioned

appropriateness of

headings/labels or

organization of information in

free-form comments.

Other

“Think-aloud” comments and

observations.

Is it easy to learn how

to use the site?

Subjective data

Response to post-

questionnaire statements:

“when I clicked on the

homepage tabs I found what I

expected”, “if I had to do it

again I could complete the

tasks I did”, “if I had to do it

again I could complete the

tasks I failed”, “finding

information on the site was

easy”, “I can find information

quickly on this site”.

References to

ease/difficulty of finding

information.

in free-form comments.

Performance data

Time to complete tasks.

Other

“Think-aloud” comments and

observations.

What kinds of

reactions do users

express while using

the site?

Observations and related

“think-aloud” comments

Does the appearance

of the site make it

pleasant to use?

Subjective data

Response to postquestionnaire

statement “the visual design

of the site made it pleasant to

use”, reference to aesthetics in

response to post-questionnaire

question “what do you like

about the site?”

What do you like

about the site?

Subjective data

Answers to this question on

the post-test questionnaire,

organized by themes

.

What do you dislike

about the site?

Subjective data

Answers to this question on

the post-test questionnaire,

organized by themes

4 RESULTS

In this section the answers to the research questions

will be addressed. For the purpose of this qualitative

study, the results of the Likert scale responses were

interpreted using the percentage of participants that

selected the various ratings. The statements in the

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

58

table below (and the tables following) are from the

post-test questionnaire. Instructions were as follows:

1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = undecided,

4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree. For the sake of brevity,

“agree” is used to include responses of “agree” and

“strongly agree”, and “disagree” to include responses

of “disagree” and “strongly disagree.”

Research Question#1. Do navigation paths meet

users’ expectations?

Table 2: Responses relating to Research Question #1.

DISAGREE UNDECIDED AGREE

Statement: Navigation paths met my expectations

90% 10% 0%

Statement: I knew where I was in relation to the

homepage at all times

30% 40% 20%

Statement: I could retrace back my path easily

20% 40% 40%

Task Performance data to measure success rate:

Task 1 – Find the Year in Which the School was

Built.

Most popular first click: About Us tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 7

Success rate: 0 out of 10

Task 2 – Find the School’s Hours.

Most popular first click on homepage: About Us

tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 3

Success rate: 9 out of 10

Task 3 – Find Information on the Gifted Program.

Most popular first click on homepage:

Academics tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 6

Success rate: 9 out of 10

Task 4 – Find Out if the School has a Clinic and a

Nurse.

Most popular first click on homepage: Staff tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 4

Success rate: 6 out of 10

Task 5 – Find the School Supplies for a 4

th

Grade

Child.

Most popular first click on homepage:

Academics tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 5

Success rate: 8 out of 10

Task 6 – Find the Size of the Student Population at

Some Point in 2015.

Most popular first click on homepage: About Us

tab

Average number of areas clicked during search

(including areas clicked more than once): 7

Success rate: 0 out of 10

Research Question#2. Is information organized

in a logical manner?

Table 3: Responses relating to Research Question #2.

DISAGREE UNDECIDED AGREE

Statement: Information was presented in a way that

made sense.

70% 30% 0%

Statement: Website was designed to meet users’ needs.

60% 40% 0%

Statement: I think the site was well laid out.

80% 20% 0%

In answers to the open-ended questions on the

post-test questionnaire, five of ten participants

mentioned “headings/labels” or “organization of

information” as something they did not like. In free-

form comments during and after the exercise, all

participants referred to the fact that “headings/labels”

were not helpful or were misleading. The tasks

eliciting these comments most frequently were the

ones initiated with clicks on the “About Us” tab—the

year the school was built, school hours, and student

population.

Nine out of ten participants thought the gifted

program was misplaced under Parent Resources in the

sidebar instead of under Academics (which was their

first click). Location of information was criticized by

seven participants in response to the post-test

questionnaire “What did you dislike about the site?”.

Six persons included location of information among

Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach

59

their suggestions for improvement on the same

questionnaire. All participants expressed problems

with the location of information in at least two tasks

in free-form comments during and after the exercise.

Research Question#3. Is it easy to learn to use

the site?

Table 4: Responses relating to Research Question #3.

DISAGREE UNDECIDED AGREE

Statement: When I clicked on the homepage menu, I

found what I expected.

70% 30% 0%

Statement: If I had to repeat it again, I could complete

the tasks I did.

60% 40% 0%

Statement: If I had to repeat it again, I could complete

the tasks I failed.

80% 20% 0%

Statement: Finding information on the site was easy.

70% 30% 0%

Statement: I can find information quickly on this site.

80% 20% 0%

In response to the open-ended questions on the

post-test questionnaire, four of ten persons said that it

took too much effort to find information on the site.

In free-form comments during and after the exercise,

all participants referred to difficulty in completing at

least three tasks (even if they did so successfully).

The tasks that elicited these comments most

frequently were the ones pertaining to the year the

school was built, the gifted program, the student

population, and the clinic/nurse.

Average time to complete tasks

Task 1 3.3 minutes

Task 2 1.7 minutes

Task 3 2.8 minutes

Task 4 2.8 minutes

Task 5 2.1 minutes

Task 6 4.4 minutes

Research Question#4. What kinds of reactions

do users express while using the site?

Observation and the think-aloud protocol yielded

much information in this regard. A number of persons

made great effort to find the information, looking at

both the school’s website as well as the County

School District’s website to which many links/tabs

led, while others (the minority) tended to give up

more quickly.

In summary, the main reaction was puzzlement

when they were unable to find what they were looking

for in what they considered to be logical places. There

were a few instances of frustration, while some

persons laughed in disbelief either at the futility of

their search or the unlikely place in which they found

what they were looking for. The sole LCU

demonstrated evidence of fatigue pretty quickly.

Body language indicated concentration for the most

part; persons stopped speaking sometimes as they

focused intently on the tasks. Below are some of the

participants’ comments:

“I feel like I am going around in circles”.

“They don’t make it easy, do they?”

“Do they even have a gifted program?”

“Seems as if they don’t want you to find it”.

“This is really frustrating”.

“I don’t know why they even have that page”

(the page behind the Administration tab).

“I found that completely by accident”.

“About Us doesn’t have anything”.

“The sidebar is weird. It’s just jumping from one

thing to the next”.

“Nice, clean homepage. Once you click on the

tabs things go crazy”.

“The order is discombobulated”.

“Visually nice but hard to use”.

“You have to work too hard to find the

information”.

“That’s a hard spot for it to be”.

“You can’t find simple stuff but you can find all

the complex stuff about curriculum”.

Research Question#5. Does the appearance of

the site make it pleasant to use?

Table 5: Responses relating to Research Question #5.

DISAGREE UNDECIDED AGREE

Statement: The appearance of the site made it pleasant

to use.

0% 40% 60%

Research Question#6. What do you like about

the site?

The themes that emerged from the questionnaire

responses to this question, in order of frequency are:

Appearance.

Content.

Diversity, readability, and “not too busy”

each got one mention.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

60

Research Question #7. What do you dislike about

the site?

The themes that emerged from the responses to

this question on the post-test questionnaire, in order

of frequency are:

Location of information (difficult to find).

Labels (tabs and headings) not reflective of

content.

Layout not logical.

Too much effort required to find

information.

Navigation back to homepage not clear.

Misalignment of information on page and

sidebar, and the use of acronyms and

unfamiliar names (such as “Discovery” for

the gifted program) each got one mention.

5 DISCUSSIONS

This study shows the importance of qualitative data

in usability testing. The quantitative data, such as the

tasks completed correctly (no prompts were given,

but generous amounts of time were allowed) does not

reveal the circuitous routes that participants took to

find the information or the frustration and complaints

expressed.

The ratings on the post-test questionnaire pose an

interesting dilemma. Though “undecided” is

supposed to represent a neutral position, in an

exercise of this nature, it in fact ends up being

negative. If a user is undecided, whether the site

functioned in a way that it should, then the website

failed in that respect. It has not fulfilled the

organization’s intent of providing its customers with

a decidedly useful resource to connect with the

company. This is, perhaps, the primary purpose

behind the development of all company/organization

websites. Dumas (1998) noted the potential for the

participants to unwittingly “distort” results through

their personal tendency to be agreeable, to avoid

extremes on a scale, and to avoid giving something a

poor rating (p.6). This may be a factor in the

undecided ratings in this study.

In hindsight, it would have been better to

disaggregate the statement “The appearance of the

site made it pleasant to use”. All participants liked

how the site looked (one person did not state it on her

questionnaire but she expressed it to the observer),

but when that was teamed with “pleasant to use” it

created a problem. The fact is they did not find the

site easy to use, but they liked how it looked in terms

if its visual design. For that reason, four persons

resorted to “undecided” in response to that statement.

The bottom line is that an aesthetically pleasing site

cannot compensate for poor functionality. This

contradicts the notion of “what is beautiful is usable?”

(Norman, 2004).

5.1 Summary of Problems Identified

The pre-test questionnaire indicated that all

participants considered a school’s website to be very

useful if they had a child going to that school. The

data that have been presented show that there are

issues with the Dunwoody Elementary school website

that, in its current form, detract from its functionality

and therefore its usefulness. The following

deficiencies were revealed, in the order of importance

to participants and also of severity in terms of its

usability.

5.1.1 Content

The content needs to be reorganized. There are many

instances in which information is not located in

logical places, that is, in places that a normal user

would think to look at, and this was the main

complaint of the study participants. Examples are the

date the school was built and the size of the school

population at some point in 2015. This information is

located in a report located under Parent Education,

which is under Parent Resources, called 2014-2015

Prospective Parent Night (Figure 2). The location of

the gifted program under Parent Resources instead of

Academics (nine of ten participants started the search

with the Academics tab) surprised many participants

as well.

Figure 2: Unexpected location of information.

5.1.2 Labels and Headings

Labels (headings and tabs) need to be more accurately

descriptive. They, in large part, do not represent what

the participants find when they click on them. The

most misleading one is perhaps the “About Us” tab,

Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach

61

which reveals only the school’s hours of operation,

and its mission and vision (Figure 3). First click

tracking shows it to be by far the most frequent

starting point for three of the six tasks. It was actually

a good starting point only for the task relating to the

school’s hours. Also misleading is the

“Administration” tab that leads to a page with only

the name of the Principal.

Figure 3: Deficient content inside About Us tab.

5.1.3 Labels and Headings

The website features a running sidebar which

functions as the main navigation tool and portal

to the problematic site layout. Eighty percent of

users did not think the site was well laid out and

this is an important measure of its usability. The

underlying problems with layout are manifested

through this sidebar, so a lot of the usability

issues expressed by users were concentrated

here. The sidebar appears to create a visual

vertical division so that when participants arrive

at a page they either focus on the sidebar, reading

the headings listed while trying to decide which

one to click, or they focus on the content of the

page to the right and ignore the sidebar. This was

very evident with the task of finding out if the

school has a clinic and a nurse. Once the Staff

tab was clicked on the homepage, at least two

persons failed to notice “Clinic” very visible in

the lineup near the top of the sidebar, and instead

went to the content of the page and searched by

location/department (Figure 4). Using this route

the Nurse is unexpectedly listed under the Front

Office department. Two persons left the page

altogether and went to explore other areas before

coming back to find out “Clinic” on the sidebar.

Figure 4: Incorrect placement of clinic tab.

Another problem with the sidebar is that the

headings are not properly formatted. One participant

remarked “The sidebar is weird. It’s just jumping

from one thing to the next. The order is

discombobulated. Things need to stick out more”.

The effect of “jumping from one thing to the next” is

caused by the fact that the contents of the sidebar are

rearranged to reflect the page that it adjoins as one

moves from page to page (note the changes in Figures

2 – 5). Furthermore, things do not “stick out more”

because the font is consistent (all caps), so such that

the existing hierarchy does not make it clearly visible.

Participants, however, like the clarity of the font, so

any redesign on this front must be approached with

caution.

A third problem with the sidebar is that on some

pages, such as Parent Resources and School Council,

there are indented lists under those headings on the

sidebar with different items than what appear on the

adjoining page to the right (Figure 3). In addition to

that, the Parent Teachers Organization (PTO) appears

both as a standalone link in the sidebar and as a link

on the Parent Resources page (Figure 5). School

Figure 5: Parent Resources heading shows different links in

sidebar.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

62

Council which is immediately under PTO on the

sidebar currently appears on the PTO website as well.

6 RECOMMENDATIONS

An encouraging point expressed by two participants

is that the site does contain useful information.

However, the three main problem areas that have

been identified—content, labels and headings, and

sidebar (related to site layout)—are inextricably

linked. Following are the proposed recommendations

based on the results of the usability test.

1. An inventory should be conducted of all the

information on the website and items

categorized within areas that would make

reasonable headings/tabs on the homepage.

Users, especially parents, should be invited to be

a part of this participatory design process. With

the aid of a diagram, categorize the information

and map out a more functional layout of the site,

to inform the redesign. The school site is not

complicated. The single-tier hub-and-spoke

structure described by Lynch and Horton (2008)

would be an ideal arrangement.

2. The “About Us” tab is standard on most

websites. This page needs to be reworked to

include more information about the school. In

addition to the school’s vision and mission,

participants indicated that they would like to see

the history of the school, enrolment statistics,

information on the principal and staff, and a

message from the principal.

3. On the homepage, all tabs should be placed in a

commanding position at the top of the page to

form the main navigation tool. Currently, there

are tabs both on the left side and at the top

(Figure 6). Three of the four tabs at the top link

to the School District; the other is labelled

“Parents” and can also be accessed at a lower

Figure 6: Main navigation tabs are located both on the left

and at the top of the webpage.

level from the sidebar. This heading does not need to

be in two places. It should remain as part of the main

navigation.

4. In order to ensure that the user knows where

he/she is at any point, the main navigation

tool from the homepage should be carried

from page to page, with a change in the color

of the heading, or bold font, to represent the

current location. In addition, users should be

able to go back to the home page from any

page. There were instances when

participants inadvertently ended up on the

DeKalb County School District’s website,

and only realized it when the back tab would

not take them back to the school’s

homepage, because another page had

opened up altogether. There should be a

message to warn users when they are leaving

the school’s website.

7 CONCLUSIONS

The Dunwoody Elementary School’s website has a

lot of potential to be a valuable resource for members

of the school community and the wider community.

If the recommendations in this report are followed,

the website will be more user-friendly. We are living

in an age of widespread Internet connectivity, both

mobile and otherwise, and websites often represent an

important point of contact with an organization as

people connect with it through its Web presence. For

parents on the go, for example, the school’s website

should be a quick and helpful point of reference from

a smartphone or the tablets. It would be a step in the

right direction for Dunwoody Elementary School to

treat its website as a virtual ambassador for the

school, to develop it with continuous usability testing,

and listen keenly to the voice of its users as it does so.

A good reference point for further testing would be

the work of Hartshorne et al. (2008), in which they

generated a checklist to assess the effectiveness of

elementary school websites. It is a very

comprehensive and expertly crafted checklist, and

provides useful parameters for the examination of the

Dunwoody Elementary school’s website in the future.

REFERENCES

Bailey, B. (2013, October 8). FirstClick usability testing

[WWW]. Available from: http://webusability.com/

firstclick-usability-testing/ (Accessed Nov 20, 2015)

Usability Testing of a School Website using Qualitative Approach

63

Battleson, B., Booth, A., Weintrop, J., 2001, Usability

testing of an academic library web site: A case study. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 27(3), pp. 188-198.

Boren, M. T. and Ramey, J., 2000, Thinking aloud:

Reconciling theory and practice. IEEE Transactions

On Professional Communication, 43(3), pp. 261-278.

Creusen, M., Snelders, S., 2002, Product appearance and

consumer pleasure. In W.D Green and P.W Jordon

(eds), Pleasure with products: Beyond Usability, New

York: Taylor and Francis, pp.69-75.

Cyr, D., Bonanni, C., Bowes, J., Ilsever, J., 2005, Beyond

trust: website design preferences across cultures.

Journal of Global Information Management 13 (4), 24–

52.

Davidson, C., 2009, Transcription: Imperatives for

qualitative research. International Journal of

Qualitative Methods, 8(2), pp. 35-52.

Dickstein, R., Mills, V., 2000, Usability testing at the

University of Arizona Library: how to let the users in

on the design. Information Technology & Libraries,

19(3), pp. 144-150.

Dumas, J.S., & Redish, J.C., 1999. A Practical Guide to

Usability testing, Intellect. Portland, OR, USA, 1

st

edition.

Egger, F.N., Cover, J.L., & Producties, J., 2003, From

interactions to transactions: designing the trust

experience for business-to-consumer electronic

commerce. Eindhoven University of Technology.

Hartshorne, R., Friedman, A., Algozzine, B., & Kaur, D.,

2008, Analysis of Elementary School Web Sites.

Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 11(1),

pp. 291-303.

Koutsabasis, P., Istikopoulou, T. G., 2014., Perceived

website aesthetics by users and designers: implications

for evaluation practice. International Journal of

Technology and Human Interaction, 9(2), pp. 39-52.

Lowry, P.B., Spaulding, T., Wells, T., Moody, G., Moffit,

K., and Madariaga, S., 2006. A Theoretical Model and

Empirical Results Linking Website Interactivity and

Usability Satisfaction. Proceedings of the 39th Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

(HICSS’06), IEEE (2006), 123a–123a.

Markle, D. T., West, R.E., & Rich, P.J., 2011, Beyond

transcription: Technology, change, and refinement of

method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(3),

pp. 1-21.

Nielsen, J. (2012, June 4), How many test users in a

usability study? Available from http://www.

nngroup.com/articles/how-many-test-users/ (Accessed

Nov 04, 2015)

Nielsen, J., 1994, Heuristic evaluation. In J. Nielsen and

R.L. Mack, eds., Usability Inspection Methods. John

Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

Nielsen, J. 1994, Usability engineering. Elsevier.

Norman, D., 2005, Emotional Design: Why We Love (or

Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books. New York, NY.

Pendell, K. D., Bowman, M. S., 2012, Usability study of a

library's mobile website: An example from Portland

State University. Information Technology & Libraries,

31(2), pp. 45-62.

Piper, T., 2012, Using school websites to support parent

engagement. Leadership, 42(2), pp. 36-38.

Preece, J., Sharp, H., Rogers, Y., 2015, Interaction design:

Beyond Human-Computer Interaction, 4

th

edn, Wiley &

Sons Ltd, West Sussex, United Kingdom.

Reporting usability test results. (n.d.). Available from

http://www.usability.gov/how-to-and-

tools/methods/reporting-usability-test-results.html.

Ross, J. (2012, February 6), Communicating user research

findings. Available from http://www.uxmatters.com/mt/

archives/2012/02/communicating-user-research-finding

s.php.

Rubin, J., Chisnell, D., 2008, Handbook of usability

testing: How to plan, design and conduct effective tests.

Indianapolis, IN: Wiley.

Sauro, J. (2011, October 19), Getting the first click right.

Available at http://www.measuringu.com/blog/first-

click.php.

Tuzun, H. et al., 2013, A Study on the Usability of a

University Registrar's Office Website through the

Methods of Authentic Tasks and Eye-Tracking. Turkish

Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(2), pp.

26-38.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.).

Research-based web design and usability guidelines.

Retrieved from www.usability.gov.

HUCAPP 2017 - International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

64