Mobile Devices and Cyber Security

An Exploratory Study on User’s Response to Cyber Security Challenges

Kanthithasan Kauthamy, Noushin Ashrafi and Jean-Pierre Kuilboer

Management Science and Information Systems, University of Massachusetts Boston, 100 Morissey blvd., Boston, U.S.A.

Keywords: Mobile Device, Cyber Security, User Response.

Abstract: In today’s increasingly connected, global, and fast-paced computing environment, sophisticated security

threats are common occurrences and detrimental to users at home as well as in business. The first and most

important step against computer security attacks is the awareness and understanding of the nature of the threats

and their consequences. Although the users of mobile devices and laptops are often the target of security

threats, many of them, specifically millennials, seem oblivious of such threats. A survey of college students

reveals that despite all the hype about cybersecurity and its potential damages, the respondents are using their

mobile devices without much apprehension or thoughts about threats, potential damages, and safeguarding

against them. This study is on the premise that as the use of mobile devices is exponentially increasing among

millennials, their laid back attitude and behaviour in response to cybersecurity is alarming and not to be

overlooked. Simple solutions such as availability of useful information should be considered.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cyber breaches have dominated headlines as attacks

targeting more and more users have grown

dramatically. Mobile technology seems to be an easy

target for cybercriminals who seek financial gain by

stealing credit card data or personal information that

can be re-sold or used for extortion. Criminal

networks have reaped immense profits and are able to

invest into investigating and developing more

sophisticated methods and skills, which are then

available through online forums for anyone to

purchase. Meanwhile, there is no dependable and

effective defence mechanism for mobile technology

to fend off such attacks. The lack of knowledge or

training to face today’s security challenges remains

an issue with the users of mobile devices.

This study revolves around “malware” and its

effects on mobile devices. Malware (malicious

software) is defined as any software used to damage

computer operations, penetrate sensitive information,

gain access to personal computer systems, or display

unsolicited advertising. These programs are designed

to infiltrate and damage computers without the users’

consent. Computer Viruses, Worms, Trojan Horses,

and Spyware, are some examples. Viruses can cause

destruction on a computer's hard drive by deleting files

or directory information. Spyware can gather data

such as credit card numbers from a user's system

without the user knowing it. The fight against these

malicious intents starts with installing anti-virus and

anti-spyware utilities on personal computers. Security

of computer information has been a national and

international concern and a topic of research for

decades (Wang, Streff, and Raman 2012; Wang et al.,

2013). Recent studies, however, have shown that most

users lack security knowledge or training to better

adapt themselves to the challenges of today’s

information security (Wash, 2010).

Building upon existing research on cyber security,

this study focuses on millennials as the growing users

of mobile devices. A sample drawn from a target

population at a public university in North East, USA.

The study is exploratory in nature and focuses on

providing a basic understanding of the effects of ever

growing malware threats on mobile devices. A

questionnaire/survey, consisting of 33 questions was

handed out to students during classroom sessions. 178

completed responses were used for data analysis.

The survey results were used to obtain descriptive

information on various aspects of user perception in

regard to awareness and protection measures against

security threats. The results reveal that despite all the

hype about cybersecurity and its potential damages,

the respondents are using their mobile devices without

306

Kauthamy, K., Ashrafi, N. and Kuilboer, J-P.

Mobile Devices and Cyber Security - An Exploratory Study on User’s Response to Cyber Security Challenges.

DOI: 10.5220/0006298803060311

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2017), pages 306-311

ISBN: 978-989-758-246-2

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

much apprehension or thoughts about threats,

potential damages, and safeguards against them.

Since millennials are a majority of mobile device

users, their laid back attitude and behavior in an

environment where cybersecurity threats are

increasingly incapacitating computing power and

generating anxiety and financial loss for individuals

and businesses should be addressed. While there is no

clear and precise solution when it comes to complex

issues surrounding cyber security, especially when it

involves human behavior, it is hoped that the users’

attitudes and responses could be influenced by more

information on the topic of cybersecurity and its

debilitating impact on a society that relies so heavily

on digital communication and exchange of

information via Internet.

The organization of the paper is as follow: next

section offers the background and literature review,

followed by a brief discussion about security threats

on mobile platforms. Next, the details of the study are

described, followed by results, conclusion, and future

research.

2 BACKGROUND AND

LITERATURE REVIEW

The concern about computer security intensified in

90s when terms such as computer virus, antivirus,

encryption, decryption, and polymorphic started

appearing in computer-related literature. At that time,

however, viruses were static programs that copied

themselves from diskette to diskette. Accordingly,

Cohen (1987) asserted that systems with limited

transitivity and limited sharing are the only systems

with potential for protection from a viral attack. He

considered ‘isolationism’, in which there is no

dissemination of information across computer systems

boundaries as the viable remedy for secure computing.

Nachenberg (1997) addressed the co-evolution of

computer viruses. Whitman (2003) examined the

nature, severity, and the frequency of information

security threats and considered deliberate software

attacks such as viruses, worms, macros, and denial of

service as the most common information security

threats.

Jesan (2006) denotes that information is the key

asset to all organizations and the main goals of

information security are confidentiality, integrity and

availability. He concluded that once these

organizations are on the internet, they automatically

become a potential target for cyber-attacks (intrusion

or hacking, viruses and worms, trojan horse, spoofing,

sniffing, and denial of service). Choi, Muller, Kopek

and Makarshy (2006) studied corporate wireless Local

Area Network (LAN) and Wireless Local Area

Network (WLAN) security issues indicating that the

old fashioned Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP)

protocol has been proven to be insecure and lacks

protection coverage for WLAN. They indicated the

importance of security standards and using the

corporate WLAN security assessment framework for

wireless information assurance. Wash (2010) reflected

on how home computer users make security-relevant

decisions about their computers and the fact that most

home users are unaware of this threat. He conducted a

qualitative study to better understand the thinking

behind the user’s daily security choices and concluded

that, since the home users are unaware of the

seriousness of the security threat; they lack the ability

to comply with recommended security system.

Companies such as TrendMicro reported 60,000

viruses identified and 400 new viruses created every

month. These viruses can affect all systems in an

organization within a split second and can create

millions of dollar of losses for the business in a

minute.

3 SECURITY THREATS ON

MOBILE PLATFORMS

Recently, mobile malware attacks have increased in

their level of sophistication. Planting malware such as

a keystroke logger or botnet code compromises the

effective use of mobile devices allowing the attackers

to do a number of criminal activities such as stealing

data, launching attacks, and inserting malware on

servers, etc. These attempts are growing in number as

more subscribers (currently 6 billion) use text

messaging (2/3 of the users), which are opened within

minutes of being received. Stolen information by data

hackers are one of the top threats. Cybercriminals take

advantage of a user’s contact list for SMS phishing

(smishing) or stolen information in the underground

market. Stolen data usually include location, network

operator, phone id and model, phone number, text

messages, and API key (application programming

interface –a value that authenticates service

users),

application id, contact list, IMEI (international mobile

station equipment identity – a number used to identify

mobile devices), and IMSI (international mobile

subscriber identity –a number used to identify

subscribers in a network” (TrendMicro Lab, 2012).

The cybercriminals have been quick to exploit the

new generation of apps for

smartphones. They

Mobile Devices and Cyber Security - An Exploratory Study on User’s Response to Cyber Security Challenges

307

sometimes, “met the demand for apps before

legitimate vendors did. Often repackaging legitimate

applications to include malware and offering it for free

on alternative channels is a main venue for malware

distribution (Gangula, Ansari, and Gondhalekar,

2013). Fake Pinterest apps appeared in the market

months before the official version came out. These

fake apps are often hosted on Russian domains, with a

domain for each fake app. More and more mobile

platforms are being targeted by threat actors and

software susceptibilities have been exploited by

cybercriminals for their malicious schemes. Android

vulnerabilities were discovered in 2012. Patching

mobile vulnerabilities may be difficult as phone

manufacturers are slow to release updates and often

customize the operating system. Application

developers assimilate advertising libraries to their

apps to produce revenue (

Vallina-Rodriguez et al., 2012).

Research shows that 90% of free apps contain ads, and

through these they found apps with ads that try to

gather information without explicitly alerting users

(

Grace et al., 2012). These ads are reminiscent of

windows adware, which afflicts desktops and laptop

and irritates users with its pop-up messages.

The prevalence of these aggressive adware

brought three major issues forward: “fraudulent text

messages: ad networks sometimes send out ads in the

form of fake text messages. This method tricks users

to click ads. User annoyance: some apps to advertisers

send out constant notifications or announcements. Not

only does this annoy users, it also contributes to

battery drainage. Data leakage: ad libraries can collect

sensitive data like GPS location, call logs, phone

numbers, and device information. One study found

that some ad libraries even made personal information

directly accessible. Ad libraries expanded the number

of parties privy to private information, which can lead

to misuse” (TrendMicro Lab, 2012).

The most common and devastating form of

malware is computer virus. When executed, it

replicates by copying itself into other computer

programs, data files, or the boot sector of the hard

drive infecting computer programs and files. Thus, it

alters the way your computer operates or stops it from

working altogether. Some of the ways you can pick up

computer viruses is through normal web activities

such as sharing music, files or photos with other users,

visiting an infected web site, opening spam email or

an email attachment, downloading free games,

toolbars, media players and other system utilities, and

installing mainstream software applications without

fully reading license agreements (Webroot, 2010).

Even the least harmful viruses can disrupt

system’s performance, “sapping computer memory

and causing frequent computer crashes.” there are

malware attack symptoms, which people should

carefully recognize to take proper caution. Such

symptoms include: slow computer performance,

erratic computer behavior, unexplained data loss, and

frequent computer crashes. According to the computer

virus statistics report (Statistics Brain) , 24 million US

households have experienced heavy spam. Within

these households, the number that have had spyware

problems was 8 million, whilst the number of

households that have had serious virus problems was

16 million. From this, one can note that virus has hit

home users more prevalently than any other type of

threats (misc. trojans, trojan downloaders and

droppers, misc. potentially unwanted software,

adware, exploits, worms, password stealers and

monitoring tools, backdoors, and spyware). Out of

these threats, virus was coined the most dominant

threat to users by 57%. The rest of the threats were

below 20%.

Malware quarterly report for 2012 for home

network infection rates has revealed that in fixed

broadband deployments, 13% of residential household

showed evidence of malware infection (Alcatel-

Lucent, 2013). This is only a slight decrease from 14%

in q2 report. High level threats, such as botnet, rootkit,

or banking Trojans, have infected 6.5% of households,

and 8.1% of households were infected with a moderate

threat level malware (spyware, browser hijackers or

adware). Based on the above data, home users are

targeted by threats every day. The effects of malware

can be highly annoying to users as an infection of a

file can lead to computer slowdown or alteration of

system functionality.

4 OUR STUDY

The Survey contained 33 questions ranging from

demographics of the users to identifying the type of

mobile devices used by the students and subsequently

comparing the degree of the vulnerabilities of various

mobile devices to malware attacks and users’

responses to such attacks, and more. 178 completed

responses were used as our sample set to perform

descriptive and predictive statistics where we tried to

draw inferences about population based on an analysis

of the sample data. Focusing primarily on descriptive

analysis, we compared and contrasted our results with

some studies involving general households to provide

a picture of how millennials’

behavior parallels to

what is known as “the norm” of the society. To

generalize the results, a set of assumptions were

identified as research questions and fall in four

categories as listed below:

WEBIST 2017 - 13th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

308

• Does the awareness of malware threats influence

security practices such as backups, encryption, or

installing anti-virus software?

• Does the anxiety related to security threat of

financial, medical, and personal information

influence security practices of installing anti-

virus software?

• Does the type of OS influence the practice of

installing anti-virus software?

• Does the type of smartphone influence security

practice of installing anti-virus software?

Statistical analysis, both descriptive and

predictive, performed on the sample data and the

obtained results are described below.

4.1 Descriptive Data Analysis

We started our data analysis with some descriptive

statistics where we sought preliminary information on

the usage of smart devices and the degree of

vulnerability as the possible target of security attacks.

Our study showed that the most popular smartphone

in our population was iPhone (66%), followed by

Android (26%), then windows phone (3%),

blackberry (2%), using no smartphone (1%), and

using some other smartphone device (2%). Our

results, based on student body at the university, are

comparable to a general study conducted by NPD in

2014. They found that more than half of US

smartphone users tended to use Apple iPhone. Apple

iPhone was used by 43% of all US smartphone owners

in the first quarter of 2016, up from 35% in 2013. This

shows a parallel between general public and student

body in regard to smart phone usage. Figure 1

illustrates the percentage of smartphones used by our

target population.

Figure 1: Types of smartphones.

The question following the type of protective

measure used by the students was to find out the level

of knowledge students had about malware. Viruses

and hackers were well known, but beyond that their

knowledge was limited: only 28% of respondents

knew a lot about computer virus and hackers, but the

majority (63%) had little knowledge or concern about

malware and their potential harm to their computer or

mobile devices. Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of

user’s knowledge about malware.

Figure 2: Knowledge about malware.

In 2012 Kaspersky conducted a similar study

targeting the general public. Their survey results

showed that 49% of laptop/pc users believe that it is

fairly safe to use internet without having any sort of

security software. These results suggest that people

are mostly unaware or/and unconcerned about the

growing malware threats and students’ responses tops

this finding by about 14%.

To find a correlation between possible protective

action and being a target of attacks, we asked if

respondents’ data/files have been hacked or infected

by a specific malware. The results showed that 83%

of the target population have been infected by some

sort of virus, 5% by hackers and 12% by both. Figure

3 illustrates the percentage of our target population

infected by virus, hacked, or experience both form of

malware.

Figure 3: Hacked versus virus infection.

The Anti Phishing Working Group (APWG)

phishing activity trends report in 2009, revealed that

49% of the 22,754,847 scanned computers were

infected with malware. Although our results are high

Mobile Devices and Cyber Security - An Exploratory Study on User’s Response to Cyber Security Challenges

309

compared to national data, one has to consider the

relative small size of the sample or we may conclude

that mobile devices used by students and generally

young people are heavily targeted by malware.

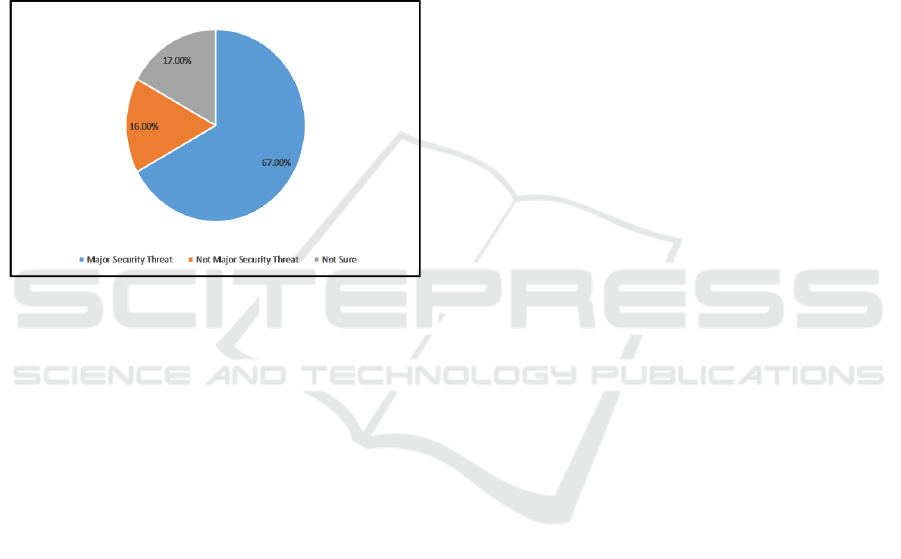

The logical flow of questioning was to find out the

respondents’ perception of the severity of threats and

their capability to take action against such threats.

Interestingly, 67% of our sampled students believe

that virus/hacking is a major security threat compared

to 5 years ago, and 16% believe it is not a security

threat, and the rest of the 16% are not sure. Figure 4

illustrates the percentage of our target population that

believe virus or hacking are indeed major threats.

Figure 4: Major security threats.

The survey also showed that 62% of students are

using antivirus software. Comparing the two results,

we see consistency in believing that virus/hacking is

a major security (67%) and the use of antivirus

software (62%). The majority of those using antivirus

software mentions that it is mid-to-very effective in

preventing viruses and only 5% say it is not very

effective. Although comforting, this could reflect an

overconfidence as research demonstrates that

antivirus software is less than effective (Thamsirarak,

Seethongchuen, Ratanaworabhan, 2015).

According to a study targeting the general public

in 2012, Kaspersky Lab (2012) showed that 36% of

smartphone users (iPhone and Blackberry), and 31%

of tablet owners do not use antivirus software.

Comparing the two studies, it seems that millennials

are ahead of the general public when it comes to

protective measures. Our results showed that 53% of

students knew how to prevent computer virus and

49% knew how to encrypt their data. Additional

probing revealed that the knowledge of ‘malware’

was slight; 81% did not know much about them.

4.2 Predictive Data Analysis

A predictive model such as regression analysis is used

to make inferences about the population. We

continued our study using collected data and

inferential statistics to test hypotheses on the

association between familiarity with computer

malware and protective measures such as using anti-

virus software, encryption, and back up. Next, we

tested the psychological effects on financial, medical,

and personal records and its impact on security

practices. Lastly, we tested the hypotheses in regard

to the students’ perception on the impact of operating

systems and type of smart phones on the practice of

protective measure against security attacks. Using

linear regression and logit model for our hypotheses,

listed below, we found no significant p-value to

conclude a reliable association between response and

dependent variables.

Hypotheses on familiarity impact:

H1: Familiarity with computer malware has a

positive impact on backup

H2: Familiarity with computer malware has a

positive impact on encryption

H3: Familiarity with computer malware has a

positive impact on using anti-virus software

Hypotheses on psychological impact:

H4: The use of antivirus software is positively

impacted by the level of anxiety caused by the

perception of breach of security on financial,

medical, and personal information.

Hypotheses on type of OS and smart phones impact:

H5: Type of OS has an impact on security practice

such as installing anti-virus software

H6: Type of smart phone has an impact on security

practice such as installing anti-virus software

In all hypotheses the dependent variable is binary

(1- yes) and (0-no) whereas response variables took

on values (1……7). Using Likert scale, respondents’

level of agreement or disagreement on a symmetric

agree-disagree scale was specified. Hence, the range

captures the intensity of respondent’s feelings for a

given item. Since the prediction will fall into one

class or the other if the response crosses a certain

threshold, the most intuitive way to apply linear

regression would be to think of the response as a

probability value. In such cases logistic regression

should be deployed.

Testing hypotheses, using the above mentioned

analysis did not show expected results. That is, with

the exception of H3 (p-value= .01), which indicated

that familiarity with malware did result in the use of

WEBIST 2017 - 13th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

310

anti-virus software, the rest of the hypotheses did not

show any significant results (i.e., H1 and H2

produced p-values of .09 and .08 respectively).

However, a larger set of sample data and perhaps

revising the survey questions may generate different

results.

5 DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION,

AND FURTHER RESEARCH

While descriptive analysis shed some light on

millennials’ attitude towards practices to safeguard

the security of mobile devices; they seem to be more

aware than general public and more inclined to take

protective measures. But, the results of predictive

analyses were inconclusive, which indicates some

contradiction between descriptive and predictive

analysis. Two reasons come to mind; the sample size

and the validity of survey questions. Therefore, we

conclude that further data collection or perhaps more

clear explanation of the intent of the study are needed

for a conclusive result.

The descriptive analysis was further enriched by

asking the reason for not using an antivirus software.

Many respondents indicated the cost of the antivirus

software, ineffectiveness of the software leading to

the notion of some students agreeing with the

researchers about lack of trust on the effectiveness of

antivirus software or the perception that the mobile

devices do come equipped with antivirus

applications. Also it was found that most students do

have antivirus software on their pcs probably because

the software was part of the purchase.

Another interesting finding was that those who do

not use security protection on their phone had the

perception that mobile devices are not susceptible to

much danger as a pc threat. This is where humans vs.

technology vulnerability lags. Today’s apps on

mobile devices carry so many advertisements and

most of those contain viruses. Since hackers and virus

coders are aware that the mobile trend is catching fast

ahead of pcs, they are always looking for ways to

exploit the mass users.

It must be noted that based on the survey, 57% of

the target population use windows and 41% use Mac

OSX operating system on their PCs. A strong

correlation between people using windows and the

number infected by viruses could be due to wide use

of Windows as the operating system in the world. A

reasonable assumption could be that hackers and

virus developer, who want to destroy as many

computers as possible, should focus of malware

specially designed for Windows users. Descriptive

results also indicated that Windows users use

antivirus software, more so than Mac OSX. A

Kaspersky Lab’s 2012 report shows that the

overwhelming majority of windows desktop (95%)

and laptop (92%) users have an antivirus program

installed on their computers.

Future study should involve a much larger sample

and could include professionals as well students to

provide a broader view on cybersecurity thereof lack

of it. Also looking into whether free Wi-Fi or secured

network brings forth malware to operating systems.

REFERENCES

Alcatel_Lucent, 2013, viewed 24 January 2017,

http://www.tmcnet.com/tmc/whitepapers/documents/w

hitepapers/2014/9861-kindsight-security-labs-

malware-report-q4-2013.pdf

Gangula, A., Ansari, S., & Gondhalekar, M. 2013, ‘Survey

on mobile computing security’, In Modelling

Symposium (EMS), European 2013 Nov 20, pp. 536-

542.

Kaspersky Lab. 2012, viewed 24 January 2017,

http://www.kaspersky.com/au/about/news/press/2012/

number-of-the-week-40-percent-of-modern-

smartphones-owners-do-not-use-antivirus-software

Thamsirarak, N., Seethongchuen, T. & Ratanaworabhan, P.

2015, ‘A case for malware that make antivirus

irrelevant’, in 12th international conference on

electrical engineering/electronics, computer,

telecommunications and information technology (ecti-

con), pp. 1-6.

Trend Micro Lab. 2012, Mobile Malware Surge from 30k

to 175k, Q3. viewed 9 November 2014,

http://www.trendmicro.com

Vallina-Rodriguez, N., Shah, J., Finamore, A.,

Grunenberger, Y., Papagiannaki, K., Haddadi, H. &

Crowcroft, J. 2012, ‘Breaking for commercials:

characterizing mobile advertising’, in Proceedings of

the 2012 ACM conference on Internet measurement

conference, pp. 343-356.

Wang, P., González, M., Menezes, R. & Barabási, A.L.

2013, ‘Understanding the spread of malicious mobile-

phone programs and their damage potential’,

International Journal of Information Security, vol. 12,

no. 5, pp. 383-392.

Wang, Y., Streff, K. & Raman, S. 2012, ‘Smartphone

security challenges’, Computer, vol. 45, no. 12, pp. 52-

58.

Wash, R. 2010, ‘Folk models of home computer security’,

In Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium on Usable

Privacy and Security, Redmond, Washington, USA, p.

11. ACM.

Mobile Devices and Cyber Security - An Exploratory Study on User’s Response to Cyber Security Challenges

311