Development of Experiential Learning System based on the

Connection between Object Models and Their Digital Contents

Collaboration between Tangible Interface and Computer Interaction

Yosuke Ota

1

, Mina Komiyama

2

, Ryohei Egusa

3,4

, Shigenori Inagaki

4

, Fusako Kusunoki

2

,

Masanori Sugimoto

5

and Hiroshi Mizoguchi

1

1

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tokyo University of Science, 2641 Yamazaki, Noda-shi, Chiba-ken, Japan

2

Department of Computing, Tama Art University, Tokyo, Japan

3

JSPS Research Fellow, Tokyo, Japan

4

Graduate School of Human Development and Environment, Kobe University, Hyogo, Japan

5

Division of Computer Science and Information Technology, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan

Keywords: Education, Object, Arduino, Kinect.

Abstract: Experiential learning is effective for educating children. However, there are many issues associated with this

technique. In this study, we describe the development of a learning support system using which learners can

experience touching and viewing in real and virtual environments. In the first stage of our study, we develop

a larval mimesis experience system consisting of a Kinect sensor, larval models, and load sensors. The system

is controlled using Arduino. Using the proposed system, learners can exercise full body interaction in the

virtual environment; specifically, they can experience how larva models are observed in the real environment.

The operation of this system was experimentally evaluated by learners from a primary school. The results

indicate that the system is suitable for the use of children. In addition, the effectiveness of the learning support

was evaluated by using a questionnaire. This paper summarizes the development of the proposed system and

describes the evaluation results.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance of natural experiential learning in

educating children is well known. In this technique,

emphasis is on teaching and learning by direct

experience (Bueno, 2015). However, some things are

difficult to experience directly, such as the habits of

extinct animals and plants, time-consuming

vegetation transition, and the habits of creatures with

remote habitation environments.

Previous studies have conducted trials on

simulating experience by reproducing the natural

environment in a virtual environment. Yoshida et al.

studied a learning experience related to extinct

animals using full body interaction (Yoshida, 2015)

(Adachi, 2013). Learning to move the body, as in a

full body interaction, has a strong effect on learning

(Yap, 2015). However, this experience is limited in

the virtual environment. Learners do not experience

real sensations, such as touching. This issue must be

addressed to improve the quality of experiential

learning.

In this study, we describe the development of a

learning support system "OBSERVE," which allows

learners to experience real and virtual environments.

We use a tangible user interface that can handle

information intuitively by using a combination of

physical objects and digital information to simulate

experiences in the real environment (Ishii, 1997).

This combines the experience of using virtual and real

environments (Ishii, 2008) and enables learners to

learn based on experiences in both. We expect that

this system will improve the learning experience.

In the first stage of this study, we develop a larval

mimesis experience system that can be experienced in

real and virtual environments. The proposed system

consists of a commercial sensor, larval models,

projector, screen, PC, and board-type computer.

Using this system, learners observe larval models,

perform interactions to identify larvae, and find latent

larvae. We expect learners to observe the larval

models and virtual environment attentively, as the

154

Ota, Y., Komiyama, M., Egusa, R., Inagaki, S., Kusunoki, F., Sugimoto, M. and Mizoguchi, H.

Development of Experiential Learning System based on the Connection between Object Models and Their Digital Contents - Collaboration between Tangible Interface and Computer

Interaction.

DOI: 10.5220/0006356901540159

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 2, pages 154-159

ISBN: 978-989-758-240-0

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

larval models are palm-sized. In this paper, we

describe the proposed system, its experimental

evaluation, and the results based on information

gathered using a questionnaire.

2 OBSERVE SYSTEM

2.1 Proposed System

In this study, we develop a system to realize

experiential learning support. The flow of the system

first requires learners to choose a larval model. We

prepared models for 15 kinds of larvae—Biston

robustus, Vespina Nielseni, Hypopyra vespertilio,

Deilephila elpenor, Apochima juglansiaria Graeser,

Celastrina argiolus, Cucullia maculosa Staudinger,

Auaxa sulphurea, Neptis philyra, Thetidia

albocostaria, Geometra dieckmanni, Xenochroa

internifusca, Langia zenzeroides nawai, Neptis

aiwina, and Sphinx caliginea caliginea. When a

particular model is selected, its corresponding image

is displayed on the screen. The larva is hidden in the

display and learners play a game to find it. After

finding the larva, the learners move their body and

perform a motion to catch the larva. Then, the larva

begins to move and an explanation of the mimicking

action is shown.

Using this system, learners not only experience

the observation of the larval model directly, but also

observe them in the virtual environment. Realizing

this requires us to implement the following two

functions: (a) creation of a larval model as a tangible

interface, and (b) operation using the learner’s body

motion. Function (a) combines the larval models and

larva in the virtual environment, while function (b)

allows us to implement experiential learning in the

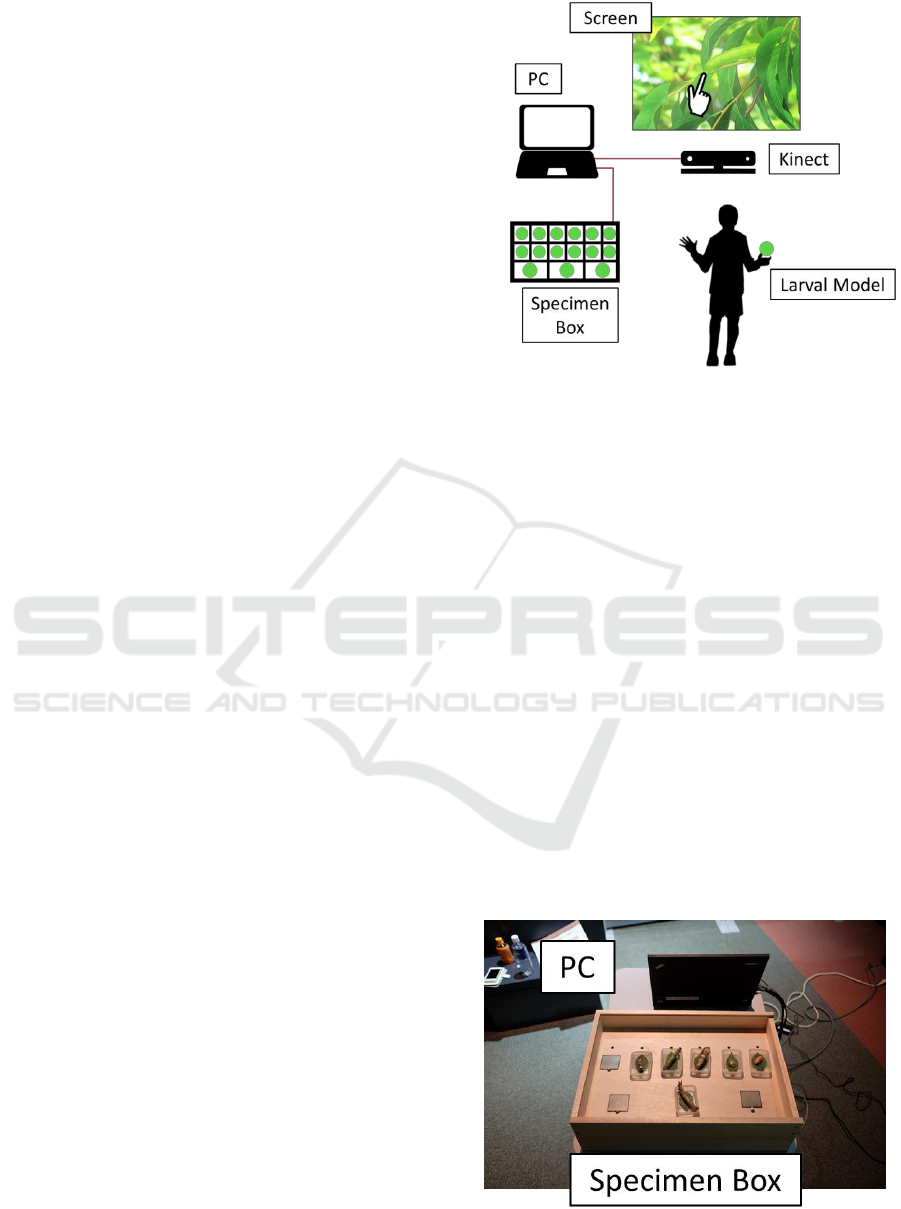

virtual environment. Figure 1 shows the setup of the

system.

2.2 Creating a Larval Model as a

Tangible Interface

Displaying the chosen larva model in the virtual

environment necessitates the development of a

recognition function for the model. We use a board-

type computer, Arduino, and load sensor, FSR(Force

Resister Sensor), to recognize the model. Arduino is

a single board-type computer using which various

sensors can be controlled (Balogh, 2010). We use

Arduino with control FSR, a sheet-like load sensor.

The resistance level of FSR varies with the size of the

added load.

Figure 1: Setup of the system. Function (a) is performed in

the specimen box. This consists of Arduino and FSR sensor.

Function (b) is performed by the Kinect sensor.

We use FSR for two reasons. First, the value of

the load is output in analog form. The system contains

multiple larval models of varying weights, and hence

the system must be adaptable to react to all of them.

Second, FSR is not affected by illumination and

temperature. In order to evaluate the proposed system,

we carried out experiments in the laboratory as well

as in a museum. Since the brightness of the

illumination in the museum differs from that in the

laboratory, the use of a sensor that remains unaffected

by this characteristic is desirable.

We incorporate Arduino and FSR in a larval

specimen box. Figure 2 shows the specimen box and

PC. Figure 3 shows a larval model. The larval models

are mounted on the FSR. When a learner picks up the

model, it gets separated from the FSR, inducing a

change in the resistance level. The system reads this

change using Arduino, and recognizes that a learner

has picked up the model.

Figure 2: Specimen box and PC.

Development of Experiential Learning System based on the Connection between Object Models and Their Digital Contents - Collaboration

between Tangible Interface and Computer Interaction

155

Figure 3: Larval model.

2.3 Operation using Learner’S Body

Motion

The system requires real-time knowledge of the

learner’s movements to reflect this on the screen. This

enables learners to experience the virtual

environment by moving their bodies. We use a Kinect

sensor to recognize the movement of the learner. This

sensor is a range image sensor, originally developed

as a home videogame device. It is highly cost

effective and can measure distance with errors in the

range of a few centimeters. Thus, the sensor can

estimate user location precisely. Additionally, this

sensor can recognize humans and their skeletons

using libraries, such as Kinect for Windows SDK.

This allows the Kinect sensor to estimate movements

associated with human body parts, such as the limbs

(Schotton, 2013).

The system enables learners to operate in a virtual

environment by using hand movements. When a

learner moves his hand, the hand pointer displayed in

the virtual environment exhibits a similar movement.

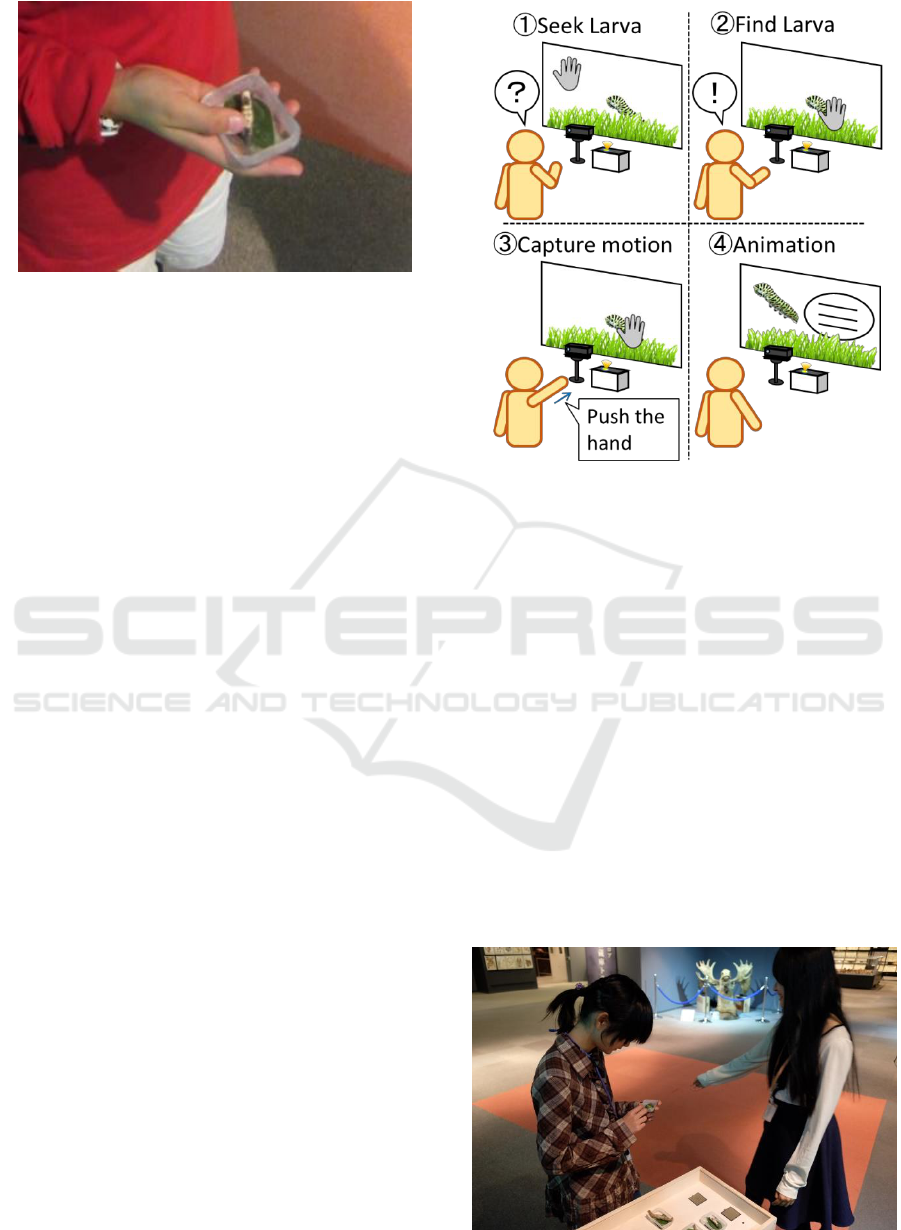

Figure 4 shows the flowchart of the procedure

followed for seeking larva. Learners look for a larva

and carry a pointer to a larva if they find it. A pointer

in the virtual environment of the hand touches the

larva when a movement is performed by pushing the

hand forward. The animation of the larva moving on

the screen is played when the system recognizes the

movement of the learner’s touch.

3 EXPERIMENT

3.1 Methods

The proposed system was evaluated by 13 fifth-grade

students (four boys and nine girls) from a national

university-affiliated elementary school. The

Figure 4: Flowchart of seeking larva.

evaluation was conducted at the H Prefecture natural

history museum. The participants tried out the system

one-by-one. Six types of larvae were prepared as

objects: Biston robustus, Vespina Nielseni, Hypopyra

vespertilio, Deilephila elpenor, Apochima

juglansiaria Graeser, and Celastrina argiolus. The

participants used all the objects and experienced the

system as described next.

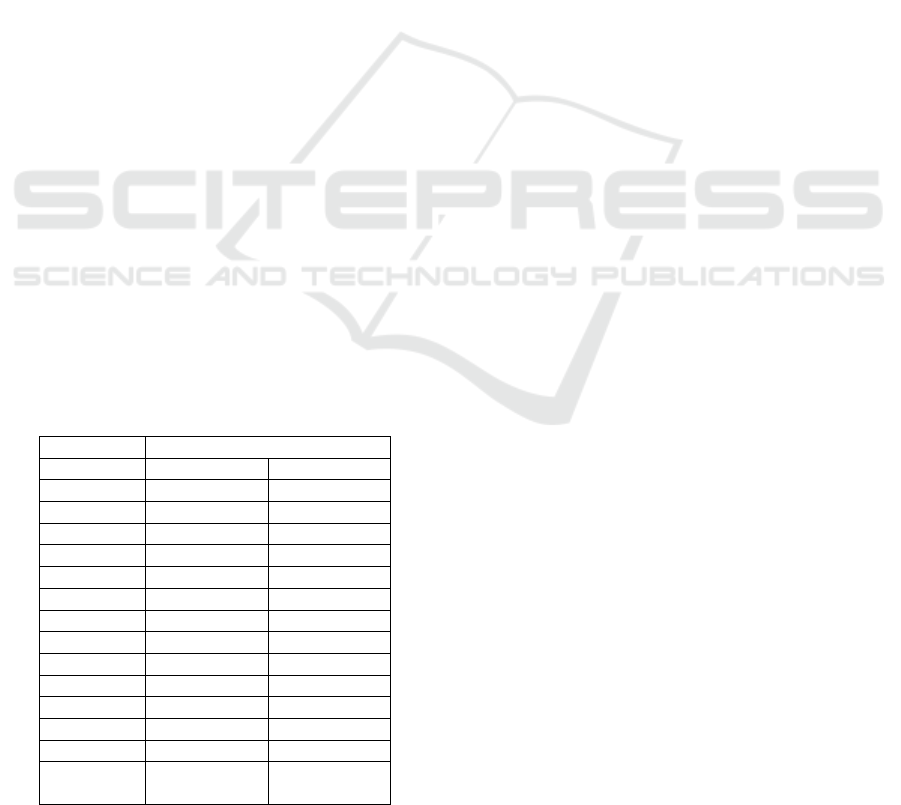

The participants began by selecting and observing

larvae from the six types of objects in the order of

their interest. Figure 5 shows the scene. When an

object is selected, animation that imitates the larvae

of the selected object appears on a screen. Participants

looked at the larvae and touched them with their

hands. Figure 6 shows the participants seeking larvae.

Once they found the larvae, the participants referred

to information on the object that appeared on the

screen, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 5: Selecting and observing larval model.

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

156

Figure 6: Seeking larvae.

Each of the participants repeated this process for

all six objects. For a chosen model, we recorded two

types of data—whether the larva emerging on screen

is right, and whether the animation shown after

discovery is played correctly. We evaluated the

system operation based on these parameters. After

trying the system, the participants viewed related

exhibits in the museum in groups of two and three.

Finally, we evaluated the system using a survey.

Figure 8 shows the participants taking the survey. The

survey comprised of 13 questions: three related to the

overall experience of the system, four of them

regarding the effect of the objects, three questions on

the experience of physical movement, and three

regarding the information provided by the animation.

Each question was scored on a scale of one to seven,

with one corresponding to “strongly agree” and seven

corresponding to “completely disagree.”

Figure 7: Referring to information.

Figure 8: Completing the survey.

3.2 Results

First, we analyze the operational evaluation. Table 1

shows the experimental results corresponding to the

operational evaluation. We recorded the number of

successes in recognizing the six kinds of larva for all

the subjects. “A” represents the result of larval model

recognition. The success rate for the total number of

trials was 98.7%. For cases in which recognition

failed, we observed that the model slipped from the

load sensor. Thus, we assume that recognition failed

because the sensor did not compute the load correctly.

“B” represents the number of times the animation

plays successfully when the learner touches the larva

in a virtual environment. The success rate was

96.15%. We observed that for cases in which the

animation failed, the leaners pushed their hand while

moving their arm violently. This caused Kinect to

recognize their movement incorrectly. From these

results, we confirm that the system can be operated

correctly by children in most situations.

Next, we describe the analysis of survey

responses. We classified responses such as “strongly

agree,” “agree,” and “somewhat agree” as positive

responses, and “no opinion,” “do not strongly agree,”

“do not agree,” and “completely disagree” as neutral

or negative responses. We then analyzed the number

of positive replies and neutral and negative replies

using a directly established calculation: 1 x 2

population rate inequality.

Three questions were about the overall system

experience. The number of positive responses for “I

developed an interest in larvae imitation,” “I

experienced the system and have a good

understanding of the museum exhibits related to

larvae imitation,” and “The system experience was

fun,” exceeded the number and neutral or negative

replies. Additionally, a significant deviation was

observed between the various responses.

Development of Experiential Learning System based on the Connection between Object Models and Their Digital Contents - Collaboration

between Tangible Interface and Computer Interaction

157

Four of the questions were related to the objects.

The number of positive replies for “I was able to

observe the larvae figures (objects) very well,” “I

observed the larvae figures (objects) from several

angles and understood some things about their

ecology,” “I understood some things about the

ecology of larvae by looking at the larvae figures

(objects),” and “The larvae figures (objects) looked

real; like they were actually alive” exceeded the

number of neutral and negative responses.

Additionally, a significant deviation was observed

between the various responses.

Three questions dealt with the physical movement

experience. The number of positive responses for “I

developed an interest in larvae imitation through the

game where I moved my body to look for the larvae,”

“I would like to learn more about larvae imitation

through the game where I moved my body to look for

the larvae,” and “I developed an interest in other

museum exhibits on imitation through the game

where I moved my body to look for the larvae”

exceeded the number of neutral and negative

responses. Additionally, a significant deviation was

observed between the various responses.

Finally, three questions were related to the

information provided by the animation. The number

of positive responses for “I developed an interest in

larvae imitation by looking at the displayed

animation,” “I would like to learn more about larvae

imitation by looking at the displayed animation,” and

“I developed an interest in museum exhibits on

imitation by looking at the displayed animation”

exceeded the number of neutral and negative

responses. Additionally, a significant deviation was

observed between the various responses.

Table 1: Experimental result of operational evaluation.

The number of success

Subject

A

B

1

6

6

2

6

6

3

6

6

4

6

6

5

6

6

6

6

6

7

5

6

8

6

6

9

6

4

10

6

5

11

6

6

12

6

6

13

6

6

Success

rate[%]

98.72

96.15

4 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we discussed the development and

evaluation of an experiential learning support system.

Operational evaluation showed that the system could

be operated correctly by children in almost all cases.

The effectiveness of the system was evaluated using

a survey that consisted of 13 questions. Out of these,

three items were on systems, four on objects, three on

the physical movement experience, and three on the

information provided by the animation. For all of

these, the number of positive responses exceeded

neutral and negative responses. There was also a

significant difference between the various responses.

These results suggest that experiencing systems,

using physical objects and physical movement,

elicited the interest and attention of the participants

toward the larvae and led to effective learning

through museum exhibits.

Furthermore, we realized that system information

provided through animation motivated the

participants and supported viewing of the object

larvae along with other related museum exhibits. In

future work, we plan to increase the types of larvae.

We will also consider a learning program that is not

limited to the object larvae, but includes observation

of live larvae outside the museum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant

Numbers JP26560129 , JP15H02936. The

evaluation experiment was supported by The

Museum of Nature and Human Activities, Hyogo. We

would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for

English language editing.

REFERENCES

Bueno, J., & Marandino, M., 2015. The notion of

praxeology as a tool to analyze educational process in

science museums. In Proceedings of the 11th

Conference of the European Science Education

Research Association (ESERA '15), Stand 9:

Environmental, health and outdoor science education,

pages 1382-1388.

Yoshida, R., Egusa, R., Saito, M., Namatame, M.,

Sugimoto, M., Kusunoki, F., Yamaguchi, E., Inagaki,

S., Takeda, Y., & Mizoguchi, H., 2015. BESIDE: Body

Experience and Sense of Immersion in Digital

Paleontological Environment. In Proceedings of the

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

158

33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA '15),

pages 1283-1288.

Adachi, T., Goseki, M., Muratsu, K., Mizoguchi, H.,

Namatame, M., Sugimoto, M., Kusunoki, F.,

Yamaguchi, E., Inagaki, S., & Takeda, Y., 2013.

Human SUGOROKU: full-body interaction system for

students to learn vegetation succession. In Proceedings

of the 12th International Conference on Interaction

Design and Children (IDC '13), pages 364-367.

Yap, K., Zheng, C., Tay, A., Yen, C., & Yi-Luen, D., E.,

2015. Word out!: learning the alphabet through full

body interactions. In Proceedings of the 6th Augmented

Human International Conference (AH '15), pages 101-

108.

Ishii, H., & Ullmer, B., 1997. Tangible bits: towards

seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms. In

Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on

Human factors in computing systems (CHI '97), pages

234-241.

Ishii, H., 2008. The tangible user interface and its evolution.

Commun. ACM 51, pages 32-36.

Balogh, R., 2010. Educational robotic platform based on

arduino. In Proceedings of the 1st international

conference on Robotics in Education (RiE '10), pages

119-122.

Shotton, J., Sharp, T., Kipman, A., Fitzgibbon, A.,

Finocchio, M., Blake, A., & Moore, R. 2013. Real-time

human pose recognition in parts from single depth

images. Communications of the ACM, 56(1), pages

116-124.

Development of Experiential Learning System based on the Connection between Object Models and Their Digital Contents - Collaboration

between Tangible Interface and Computer Interaction

159