Pro-Natalism Policy, Demography and Democracy - Nonlinear Dynamics

Analysis

Tal Mor and Yair Rezek

Computer Science Department, Technion, Haifa 3200003, Israel

Keywords:

Political Demographics, Natality, Data-driven Models, Cultural Models, Complex System, Nonlinear

Dynamics.

Abstract:

Pro-natal policies, namely promoting human reproduction, are common in many societies, often due to reli-

gious, nationalistic, or ethnic reasons. If successful, such policies can have detrimental enviromental impact,

increase demand for natural and economical resources, and may lead to demographic changes with poliical

consequences. Hence, high fertility rates deserve careful analysis. Here we study, using linear dynamics and

non-linear dynamics tools, how high fertility rates may impact demography in Israel. We further comment on

potential implications of such scenarios for democracy in Israel.

1 INTRODUCTION

There have been many cases in recent history where

social and ethnic groups encouraged their members

to increase their fertility (pro-natality) for religious,

nationalistic, or political reasons.

In Quebec, Canada, for example, the “revenge of

the cradle” (“La Revanche du berceau” in French)

policy was encouraged by Quebec patriots in order

to increase their influence and power and attain their

nationalistic and political aims (Morland, 2016); we

note that after these aims were largely achieved, in the

1960s, this policy subsided. Similarly, in Iran follow-

ing the Islamic revolution and especially in the wake

of the Iran-Iraq war, pro-natal policies were enacted

explicitly to grow the nation and foster its strength

(Baktiari, 1995); we note that after realizing their eco-

nomic cost, Iran switched to promoting family plan-

ning (Abrahamian, 2008), until recently rescinding

support for such policies for cultural as well as prac-

tical reasons.

“Demographic warfare” of this sort is also preva-

lent in Israel, in various ways. In the context of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict, both sides have explicitly

and often officially encouraged natal policies to in-

crease their relative population size (Morland, 2016).

The Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat famously said

that “the womb of the Arab woman is my strongest

weapon”, for example, while Israel’s founder Ben Gu-

rion explicitly set out a natality committee to bol-

ster Jewish reproduction (Schiff, 1981). Such de-

mographic warfare may be especially effective in ex-

plaining the high Palestinian fertility rates (Fargues,

2000).

However, not all demographic shifts of this sort

are due to an officially-declared or intentional de-

mographic “warfare”. In Lebanon, population sizes

change rapidly, with a high Shiite fertility rate being

a key factor, but there is no indication that this is by

design (Faour, 2007). Similarly, it has been argued

that in the USA the high fertility of the religious-right

compared to the liberal left will in the future shift the

politics of the nation to the right (Kaufmann, 2010;

Morland, 2016).

In this paper, we would like to focus on another

pro-natal case in Israel. The fertility rates of the Jew-

ish population in Israel are sharply divided along re-

ligious lines (Levi, 2016). Among the ultra-Orthodox

Jews, in particular, religious, social, and political

factors combine to form a strong pro-natal effect,

producing a high fertility rate of approximately 6.9

(Friedlander, 2009). The rest of Israeli Jewish soci-

ety has a much lower fertility rate (2.84 on average).

This disparity could potentially lead to a major demo-

graphic change. In the past, this did not occur as the

large difference in fertility rates was balanced (over

the last half century) by immigration, and in partic-

ular by a massive post-Soviet immigration (consist-

ing mainly of secular Jews and non-Jews with Jewish

roots) in the decade around 1990-1995. Given the cur-

rent worldwide Jewish demographics, such a massive

immigration is unlikely to repeat itself (DellaPergola,

124

Mor, T. and Rezek, Y.

Pro-Natalism Policy, Demography and Democracy - Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0006367301240129

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk (COMPLEXIS 2017), pages 124-129

ISBN: 978-989-758-244-8

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2016).

Our goal in this paper is to explore the expected

future demographic changes implied by these high

fertility rate differences using the tools of dynamical

analysis.

2 DEMOGRAPHICS OF ISRAELI

ULTRA-ORTHODOX

(HAREDIM)

In Israeli society, fertility rates vary greatly between

religious subgroups. The largest population group

(secular Jews) has a total fertility rate of 2.1 (as of

2014; see (Levi, 2016)), while the ultra-Orthodox

Jews, or ”Haredi”, population has a fertility rate of

6.9. Notwithstanding causal models of fertility rate

dynamics (Berman, 2000; Berman et al., 2012; Man-

ski and Mayshar, 2003), all Jewish religiosity sub-

groups had a fluctuating but fairly stable fertility rate

for the past four decades or so (Levi, 2016), so it is not

likely that these fertility rates will vary greatly in the

near future. It is this unique stability and contrast of

the fertility rates that motivates our study. The tools

of complex-systems and nonlinear-dynamics can be

used to provide a more careful analysis of the dy-

namics than a simple projection based on the fertility

rates.

We note that a fuller analysis of Israel’s future

demographics will need to consider also the sizable

Arab minority within Israel (comprising about 20%

of the population). As their fertility rates have not

been stable, however, such an analysis is beyond the

scope of this position paper, and we focus only on the

more stable Jewish populations.

Further information on the Israeli population can

be obtained from the Israeli Central Statistics Bureau.

It divides the Jewish populace to five levels of re-

ligiosity: Nonreligious or secular (“Hiloni”), tradi-

tional but nonreligious (Masorti Lo-Dati), traditional

religious (Masorti Dati), religious (Dati), and ultra-

orthodox or Haredi. As can be seen in Table 1,

most Israeli Jews consider themselves to be Secular

or Traditional-nonreligious.

These statistics relate to the respondent’s current

level of belief. However, a person’s current level of

religious observance may not be the same as the one

he was raised in. The Israeli Central Bureau of Statis-

tics has also provided, for limited years (2002-2012),

information about the level of religiosity of the house-

hold the person was raised in at age 15. The data for

the 2012 census is shown in Table 2. Note that the

CBS data does not include the last two entries in the

Table 1: Religiosity levels of Israeli Jews.

Current Religiosity Tot Pop

Total 3896707

Haredi 366851

Religious 389707

Trad. Rel. 533096

Trad. Nonrel. 885071

Secular 1721982

Haredi Home column, but does imply 5707 people

in these categories (without noting how they are dis-

tributed between the two, since the numbers are very

small and hence the relative uncertainty in them is too

high). Our analysis below is unaffected by the spe-

cific distribution.

The CBS survey indicates a high retention rate for

the extreme levels of religiosity (secular and ultra-

orthodox), and a marked tendency for the society as

a whole to secularize. If all religiosity groups grew at

similar rates, then, Israeli society would be projected

to becomes more secular but more polarized in time,

with a large secular and Haredi population and few in

between.

As already discussed in the introduction, the fer-

tility rates of the religiosity subgroups vary signifi-

cantly. According to (Levi, 2016), the latest (2014)

total fertility rates of the different groups are 6.9

Haredi, 4.2 Religious, 4 Traditional Religious, 3 Tra-

ditional Nonreligious, and 2.1 Secular. While the fer-

tility rates fluctuate in time, they remained fairly sta-

ble for the past decades, and we shall assume them

to be constant for our initial (linear) analysis. If we

assume the total fertility rate to be (twice the) growth

rate per single generation, this implies that on average

two secular people will become 2.1 people in the next

generation, while two Haredi people will become 6.9

people. The Haredi relative population size can hence

increase very substantially even within a single gen-

eration.

For simplicity, we shall divide the population into

two groups: the Haredi, and everyone else (denoted

as populations H and E below). (We note other di-

visions are possible, e.g. (Pew, 2016) used a di-

vision of Haredi, Religious, Traditional, and Secu-

lar; we leave such analysis to the journal version of

this paper). Normalizing for group size, according to

the above table, gives a total fertility rate of 6.9 for

Haredi and 2.84 for everyone else. These rates corre-

spond to a change per generation, or growth rate, of

r

H

= 6.9/2 − 1 = 2.450 for Haredi, and r

E

= 0.422

for everyone else.

The above table can also be used to derive the

retention and transition rates between the religious

Pro-Natalism Policy, Demography and Democracy - Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis

125

Table 2: Religiosity of Israeli Jews, by the religiosity of the household they were raised in at age 15. The first column denotes

the current level of religiosity, the next the total population at the level of religiosity, then the number of people raised at a

Haredi household (at age 15), the ones raised in a Religious household, those raised in a Traditional-Religious household, a

Traditional Nonreligious household, and finally a secular or non-religious household. Data is from the 2012 Social Survey by

the Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel; note that two entries are missing from the table, see discussion in the main text.

Current Religiosity Tot Pop Haredi Home Rel. H. Trad.-Rel. H. Trad. Nonrel. H. Secular H.

Total 3896707 287057 590818 713571 725369 1576014

Haredi 366851 257989 32554 31375 14927 30006

Rel. 389707 12485 274574 57449 20080 24517

Trad. Rel. 533096 10876 106243 320440 55549 39330

Trad. Nonrel. 885071 - 124182 206257 391211 161028

Secular 1721982 - 53264 98049 243602 1321133

groups. The Haredi retention rate per generation is

c

H→H

= 0.899, while their transition rate is c

H→E

=

0.101. For everyone else, the retention rate is c

E→E

=

0.970 and the transition rate is c

E→H

= 0.030.

3 OUR BASIC EQUATIONS

We consider populations changing in time according

to dynamical (ordinary differential) equations, such as

(for the case of linear equations)

˙

H = (r

H

− c

H→E

)H + c

E→H

E (1)

˙

E = c

H→E

H + (r

E

− c

E→H

)E (2)

Here the dot indicates the derivative with respect to

time. These equations describe the dynamics of the

populations of the Haredi (H) and everyone else (E)

in units of generation time. With the above choice of

parameters, our basic equations are:

˙

H = 2.349H + 0.030E (3)

˙

E = 0.101H + 0.392E (4)

These linear equations can be solved exactly ana-

lytically. Starting from the initial populations H =

366,851 and E = 3, 529, 856 in 2012 (according to

Table 2), the projected populations fit very well to

the limited historical record (stretching from 2002 to

2015).

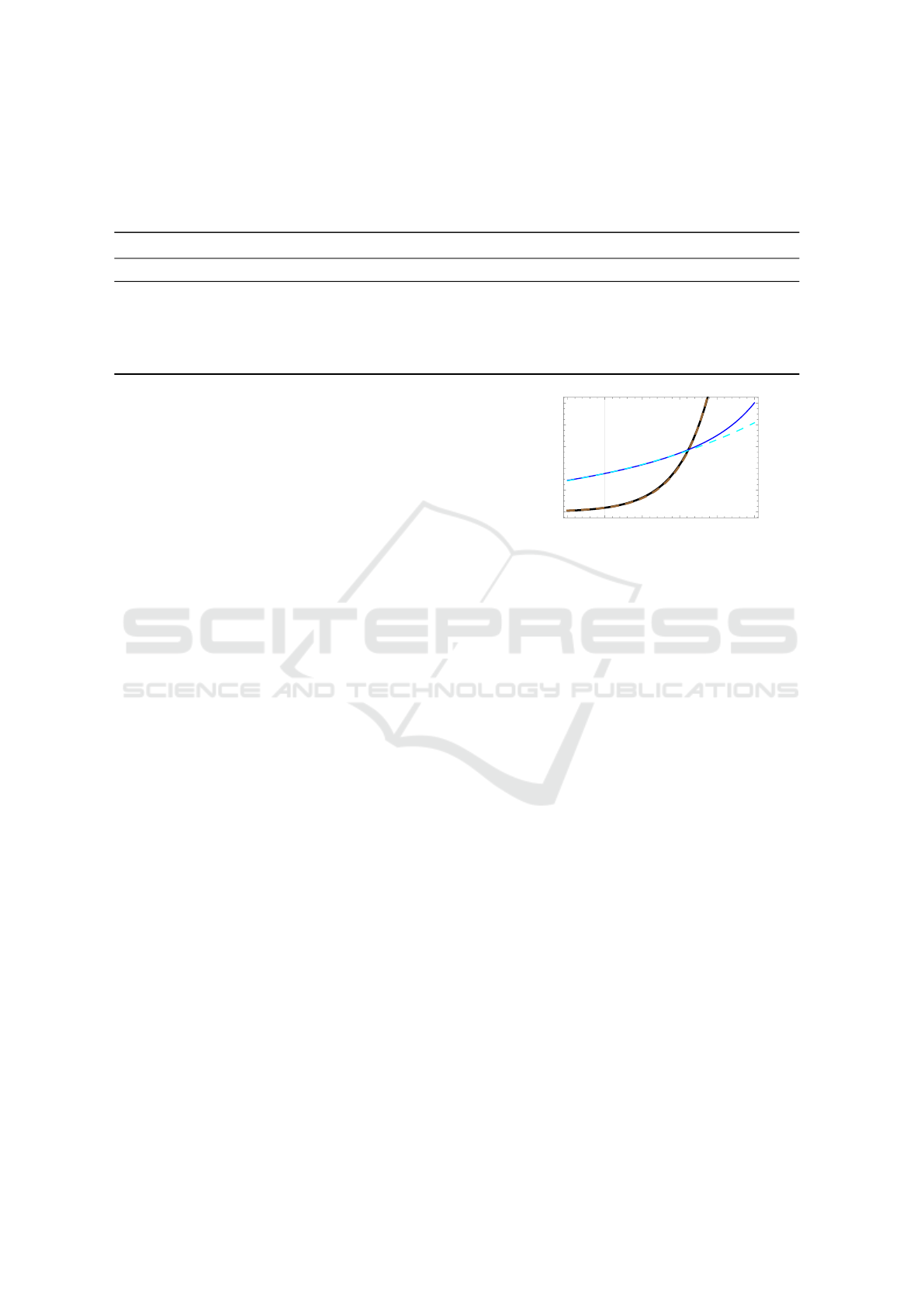

Under this model, the Haredi population quickly

explodes so that it surpasses everyone else within

about 1.1 generation (see Fig. 1; for the mathematical

derivation leading up to it, see Sections 4 and 5). This

is due to its high fertility rate. As can be seen from

the figure, conversion between the religiosity currents

has little effect on this growth. The difference in fer-

tility rates is thus expected to completely overwhelm

the secularization process in Israel.

-0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10 000

Generations since 2012

Population [1k]

Figure 1: The Jewish religious populations of Israel from

-0.5 to +2.0 generations from 2012. The solid thick (black

online) line marks the Haredi population, while a solid thin

(blue online) line marks the E population. The H popula-

tion becomes dominant approximately 1.1 generations after

2012. Dashed (brown and cyan online) lines mark the popu-

lation dynamics in a model without conversion between the

two populations. For both populations, the effect of reli-

gious conversion is initially so small as to be unnoticeable,

so that the dashed lines lie on top of the solid lines.

4 DYNAMIC ANALYSIS IN

GENERAL

For any dynamic system, one generally wants to ob-

tain a global understanding of its dynamics. This can

be done by considering the system’s fixed or station-

ary points (the points at which the system stays con-

stant, unchanging), and seeing how the system be-

haves near them so as to obtain a global view of how

it flows between fixed points. One therefore always

wishes to explore the dynamics near the stationary

points (

˙

H = 0,

˙

E = 0, ...), and from that deduce the

overall picture of the dynamics (see, e.g. (Glendin-

ning, 1994)). For a one-dimensional system ˙x = f (x),

the system will have a stable stationary point if the

derivative d f /dx is negative at the stationary point,

i.e. when d f /dx|

x

∗

< 0 with x

∗

being a stationary

point so that ˙x|

x

∗

= f (x

∗

) = 0.

Similarly, for a multi-dimensional problem we

now have multiple f functions, ˙x = f

1

, ˙y = f

2

,.... We

need to look at the Jacobian of the problem, namely

COMPLEXIS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

126

the matrix J

ik

= ∂ f

i

/∂x

k

. Intuitively, directions where

these partial derivatives are less than zero at the sta-

tionary points will be the stable directions; but we

need not be limited to just these axes, so it is better

to consider the problem more abstractly and look for

the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix. If all are neg-

ative at the stationary point, then it is stable.

5 LINEAR HOMOGENEOUS

CASE WITH TWO

POPULATIONS

For our basic, linear, equations, we have only two di-

mensions, and the equations are linear so each is a

line. The Jacobian is simply the matrix of coefficients

J =

2.349 0.030

0.101 0.392

(5)

Analysis of dynamical equations can be done by con-

sidering the ”null-clines”, i.e. the lines where the

derivatives are zero. Where these intersect, all the

derivatives are zero so the point is stationary. In our

case, the nullclines are not within the physical range,

which is that of positive populations. Nevertheless,

considering them will allow us to better understand

the dynamics as a whole. Nullclines will also be more

useful in the following, non-linear, analysis.

To understand the dynamics, we can consider the

vector field of the population change; we have drawn

it explicitly for this case in Fig. 2. The line of

˙

H = 0

(the H ”nullcline”) intersects the line of

˙

E = 0 (the E-

nullcline) at a single point, which is the origin (0,0).

This is the sole stationary point. At this point both f

i

increase with E and with H, having positive deriva-

tives, so clearly the point is unstable.

The realistic case, with positive populations, is

above both nullclines, so that both E and H are in-

creasing indefinitely. If we include negative popula-

tions in our analysis, however, we can understand the

dynamics better. In the area below the H-nullcline,

H is decreasing, and in the area below the E-nullcine

E is decreasing. Overall, the dynamics is a ”running

away” from the origin (zero populations)

How can immigration be incorporated into such a

dynamic analysis? In the 90’s, Israel saw a large in-

flux of primarily-secular-Jews from the former USSR.

Such a scenario can be simplified to a sudden jump of

approximately 1 million in E (everybody who is not

Haredi), or by explicit time-dependent models. Anal-

ysis of the impact of the such immigration will be pro-

vided in the full (journal) paper.

-5000 0 5000

-6000

-4000

-2000

0

2000

4000

6000

Figure 2: The population change field (

˙

H,

˙

E) as a function

of H and E (H on the x-axis, E on the y-axis), for the sim-

ple (linear) model. The H-nullcline is the (blue) line near

the horizontal axis, and divides the area where H increases

from where it decreases; the E-nullcline is the dashed (red)

line, and delimits where E decreases or increases. The null-

clines meet at a single point (at the origin), which is the

only stationary point. It is unstable, with populations ”run-

ning away” from it. The circle indicates the current popula-

tions (as of 2012), and the square indicates the point where

the Haredi population will start to surpass everyone else ac-

cording to the linear model.

6 NON-LINEAR DYNAMICS

Constant high birth rates are ultimately not sustain-

able. There is good reason to think they are unsustain-

able even in the relatively near future (Biello, 2009).

But even if they will decline, how will they do so?

We speculate that the relative fraction of the popula-

tion may be a major factor, and introduce a simple

change to the basic dynamic equations which reflects

this. According to this (non-linear) model, the Haredi

birth rate will drop as their fraction in the population

grows,

˙

H = (r

0

H

− c

H→E

− δ

H

H + E

)H + c

E→H

E (6)

˙

E = c

H→E

H + (r

E

− c

E→H

)E (7)

Our speculated (nonlinear) model assumes, for sim-

plicity, that the drop in fertility is linear with H/(H +

E). For this model, we need to choose the parame-

ters r

0

H

and δ so as to maintain two constraints - to

preserve an effective Haredi growth rate (including

the δ term) of 2.45 at 2012, and to receive some de-

sired effective Haredi growth rate at the large H limit

(H E). We will choose the latter, large H limit,

growth rate to be equal to the non-Ultra-orthodox

growth rate r

E

. With this choice, the dynamical equa-

tions become:

Pro-Natalism Policy, Demography and Democracy - Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis

127

-0.10 -0.05 0.00 0.05 0.10

-0.02

-0.01

0.00

0.01

0.02

Figure 3: A distorted view of the populations change field

(

˙

H,

˙

E) as a function of H and E, for the non-linear model,

zooming in on the origin. The size differences of the arrows

has been reduced to allow one to see arrows of vastly dif-

ferent sizes. Note that the finite size of the arrows makes

the dynamics near the singularities (which are close to the

horizontal axis) unclear; separate plots for each component

will be provided in the journal version to clarify this region.

˙

H = 2.560H + 0.030E − 2.239

H

2

H + E

(8)

˙

E = 0.101H + 0.392E (9)

In these equations, we have set r

0

H

−δ(H/(H + E)) =

r

H

for the initial populations, and r

0

H

− δ = r

E

.

The H-nullcline (

˙

H = 0) in this case is no longer

a line; as can be seen in Fig. 3, it consists of two

lines. The equations are not defined at the origin,

but the origin effectively serves as an unstable sad-

dle point. The full paper will provide a more detailed

analysis of the behavior of this system in the negative-

populations domain (such an analysis which is vital to

ensure it doesn’t behave unexpectedly in the positive-

populations domain, and potentially interesting on its

own from a complex-systems point of view). Fo-

cusing on the real (positive populations) part (Fig. 4),

one can see that the dynamics is still quite similar to

the linear case.

The main point of difference is that the growth of

the Haredi population is slower at long times, so that

the point at which the Haredi overpass everyone else

is delayed to approximately 1.4 generations (instead

of 1.1 generation in the linear model), as can be seen

in Fig. 5.

7 DISCUSSION

Due to their past consistency (Levi, 2016) and the sta-

bility of the political factors (Friedlander, 2009), we

have suggested the Haredi population will maintain

their high fertility rates in the foreseeable future. Our

analysis indicates that this implies that under a linear

0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

Figure 4: The populations change field (

˙

H,

˙

E) as a function

of H and E, for the non-linear model, for positive popula-

tions. The dynamics are overall similar to the linear model,

with the same initial position in 2012 (circle). The point

where the two populations meet (square) is more distant in

comparison to the linear model.

-0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10 000

Generations since 2012

Population [1k]

Figure 5: The populations of H and E in time, in units of

generations from 2012. The nonlinear model is the dashed

line, the linear model the solid line; H population is the thick

(black) line, E is the narrower (blue) line. The H population

overtakes the E population later in the non-linear model.

model the ultra-Orthodox will become the majority

group within 1.1 generations from 2012; assuming a

generation time is about 30 years, this is circa 2040.

We have shown that the dynamics are not signif-

icantly affected by whether or not religious conver-

sion is included in the model, as religious conversion

is too slow to affect them appreciably. The high reli-

gious fertility completely overwhelms the seculariza-

tion process in Israel.

Due to the past stability of the fertility rates it is

likely that any model will not drastically change the

projection for the near (0.5-1 generations) future. It is

difficult to make predictions beyond this point, espe-

cially as the examples of Iran or Quebec show that af-

ter the goal of a pro-natalism policy is reached, fertil-

ity rates may drop and change drastically. Therefore,

due to the examples of Iran and Quebec, we have cho-

sen a speculative and simple non-linear model with a

fertility rate that drops with time. This model pushed

the point of transition into an ultra-Orthodox domi-

nance from 1.1 to 1.4 generations (i.e. from 2040 to

2055 or so).

COMPLEXIS 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk

128

We note that in all the above calculations, error

bars and error analysis were excluded due to uncon-

trolled uncertainty in the model (the assumption of

constant fertility rate, for example, would certainly be

strictly false). In particular, we choose a non-linear

model which is linear in H/(H + E) as a demonstra-

tive example, but there is no guarantee that this choice

would be a good parametrization. We believe data

from other places (such as Iran and Quebec) is insuf-

ficient in order to justify a specific model. The esti-

mated numbers in Table 2 are also highly uncertain,

with some uncertainties in the range of 30% or more.

Despite all this, we expect our results to be relatively

stable to actual plausible errors (past history suggests,

for example, that the fertility rates will only fluctuate

slightly, and a different non-linear model will behave

similarly in the near future).

The extension of the dynamics into the domain

of negative populations allows us to utilize the tools

of dynamical analysis to understand the system. We

have seen that in the simple, linear, model zero popu-

lations is the sole unstable stationary point, which the

populations ”run away” from. The addition of nonlin-

earity considerably complicates the dynamics in the

non-positive domain, and may complicate the null-

clines and dynamics there. For our non-linear model

the origin effectively serves as an unstable saddle sta-

tionary point, attracting the populations in part of the

negative-populations domain. The origin remains un-

stable in the positive-populations domain, for both the

linear and the non-linear domain.

The political views of the ultra-Orthodox are strik-

ingly different from those of the currently-dominant

secular Jewish group in many respects, especially

those related to democratic and religious values. For

example, 69% of the ultra-Orthodox believe Israel is

too democratic, whereas 59% of the secular Jews be-

lieve it is too religious (Hermann et al., 2016). As the

Haredi population will become dominant, more and

more of its values may be made into laws and pol-

icy. These include favoring religious law over secu-

lar law, favoring government actions to promote (or-

thodox) Jewish religion, and imposing religious law

(halacha) as the state law (Pew, 2016), as well as ex-

cluding women from public life (never has a women

been nominated to parliament by an ultra-Orthodox

party, for example), privileging Jewish citizens (Her-

mann et al., 2016), and more. According to our demo-

graphic model, then, Israel is set to undergo substan-

tial legal and political change in the coming decades,

and will become a less democratic and more religious

state.

This research was supported by the Israeli MOD.

REFERENCES

Abrahamian, E. (2008). A history of modern Iran. Cam-

bridge University Press.

Baktiari, B. (1995). Ervand abrahamian, khomeinism: Es-

says on the islamic republic (berkeley: University of

california press, 1993). pp. 182. International Journal

of Middle East Studies, 27(03):382–383.

Berman, E. (2000). Sect, subsidy, and sacrifice: an

economist’s view of ultra-orthodox jews. The Quar-

terly Journal of Economics, 115(3):905–953.

Berman, E., Iannaccone, L. R., and Ragusa, G. (2012).

From empty pews to empty cradles: Fertility decline

among european catholics. Technical report, National

Bureau of Economic Research.

Biello, D. (2009). Another inconvenient truth: The world’s

growing population poses a malthusian dilemma. Sci-

entific American.

DellaPergola, S. (2016). World jewish population, 2015.

In American Jewish Year Book 2015, pages 273–364.

Springer.

Faour, M. A. (2007). Religion, demography, and politics in

lebanon. Middle Eastern Studies, 43(6):909–921.

Fargues, P. (2000). Protracted national conflict and fertility

change: Palestinians and israelis in the twentieth cen-

tury. Population and Development Review, 26(3):441–

482.

Friedlander, D. (2009). Fertility in israel: Is the transition to

replacement level in sight? In Completing the Fertility

Transition, page 403. United Nations publication.

Glendinning, P. (1994). Stability, instability and chaos:

an introduction to the theory of nonlinear differential

equations, volume 11. Cambridge university press.

Hermann, T., Heller, E., Cohen, C., Bublil, D., and Omar,

F. (2016). The Israeli Democracy Index 2016. The

Israeli Institute for Democracy.

Kaufmann, E. (2010). Shall the religious inherit the earth?:

Demography and politics in the twenty-first century.

Profile Books.

Levi, A. (2016). The total fertility rates in israel by reli-

gion and level of religiosity and their affect on pub-

lic spending. The Knesset Research and Information

Center, Israel. This is a governmental report, submit-

ted to the Finance Committee.

Manski, C. F. and Mayshar, J. (2003). Private incentives and

social interactions: Fertility puzzles in israel. Journal

of the European Economic Association, 1(1):181–211.

Morland, P. (2016). Demographic Engineering: Population

Strategies in Ethnic Conflict. Routledge.

Pew (2016). Israels Religiously Divided Society. Pew Re-

search Center.

Schiff, G. S. (1981). The politics of fertility policy in israel.

Modern Jewish Fertility, 1:255.

Pro-Natalism Policy, Demography and Democracy - Nonlinear Dynamics Analysis

129