Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability

Framework for South Africa

Paula Kotzé

1,2

and Ronell Alberts

1

1

CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa

2

Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Keywords: e-Government, e-GIF, Interoperability.

Abstract: In September 2016, the South African Government published a White Paper on the National Integrated ICT

Policy highlighting some principles for e-Government and the development of a detailed integrated national

e-Government strategy and roadmap. This paper focuses on one of the elements of such a strategy, namely

the delivery infrastructure principles identified, and addresses the identified need for centralised

coordination to ensure interoperability. The paper proposes a baseline conceptual model for an e-

Government interoperability framework (e-GIF) for South Africa. The development of the model

considered best practices and lessons learnt from previous national and international attempts to design and

develop national and regional e-GIFs, with cognisance of the South African legislation and technical, social

and political environments. The conceptual model is an enterprise model on an abstraction level suitable for

strategic planning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Implementing a citizen-centric approach, digitising

processes and making organisational changes to

delivering government services are widely posited as

a way to enhance services, save money and improve

citizens’ quality of life (Corydon et al., 2016). The

term electronic government (e-Government) is

commonly used to represent the use of digital tools

and systems, combined with organisational change

and new skills, to provide better public services to

citizens and business, better democratic processes

and to strengthen support to public policies

(European Commission, 2017). To gain full benefit

of digitisation and data, governments need to deliver

on four key imperatives: gaining the confidence and

buy-in of citizens, business and public leaders;

conducting a skills and competencies revolution;

redesign the way in which government operate; and

deploy enabling technologies that ensure

interoperability and the ability to handle massive

data flows (Tadjeddine and Lundqvist, 2016).

Although all of these aspects are important and

should be addressed, this paper primarily focuses on

the interoperability aspect.

e-Government interoperability is broadly defined

as “the ability of constituencies to work together”

(Lallana, 2008: p.1) and is becoming an increasingly

crucial issue, also for developing countries (United

Nations Development Programme, 2007). Many

governments have finalised the design of national e-

Government strategies and are implementing priority

programmes. However, many of these interventions

have not led to more effective public e-services,

simply because they have ended up reinforcing the

old barriers that made public access cumbersome.

The e-Government promise of more efficient and

effective government are not being met mainly due

to the ad hoc deployment of information and

communication technology (ICT) systems.

Governments should rather strive towards

interoperable deployments that share and exchange

data and aggregate public services into a single

service window, allowing for seamless flow of

information across government and between

government and citizens (United Nations

Development Programme, 2007).

Interoperability in the context of e-Government

addresses the need for cooperation; exchanging

information and reusing information among public

administrations, in order to improve public service

delivery to citizen and businesses at a lower cost,

improve decision making and enable better

governance (European Union, 2011, Lallana, 2008).

Kotzé, P. and Alberts, R.

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa.

DOI: 10.5220/0006384304930506

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2017) - Volume 3, pages 493-506

ISBN: 978-989-758-249-3

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

493

On a technical level, interoperability refers to

two or more ICT systems, or components, to transfer

and exchange information in a uniform and efficient

manner across multiple organisations, and to use the

information exchanged (IDABC, 2004, Department

of Finance and Administration, 2006, Lallana,

2008). The European Union defines interoperability

in the context of public service delivery as “the

ability of disparate and diverse organisations to

interact towards mutually beneficial and agreed

common goals, involving the sharing of information

and knowledge between organisations, through the

business processes they support, by means of the

exchange of data between their respective ICT

systems” (European Union, 2011: p.2).

Interoperability therefore refers to more than just the

technical or the ICT system level, and affects an

extended enterprise across diverse organisations.

Enterprise modelling aims to offer different, but

complementing, views on an enterprise to encourage

dialogues between various stakeholders (Frank,

2009). Enterprise models can include abstractions

suitable for strategic planning, organisational design

or redesign, and software engineering. Enterprise

models can be regarded as the conceptual

infrastructure to support a high level of integration

of various software or enterprise components, and

reuse of models, concepts, or code.

An e-Government interoperability framework (e-

GIF) is a document (or set of documents) that

specifies a set of common elements for an extended

enterprise of authorities, agencies or organisations

that wish to work together towards the joint delivery

of public services (Lisboa and Soares, 2014,

European Commission, 2010b). As such, an e-GIF is

regarded a special kind of enterprise model aimed at

providing conceptual guidance towards developing

an e-Government eco-system of enterprises.

Common elements of an e-GIF include policies,

guidelines, principles, standards, vocabularies,

concepts, recommendations and practices (European

Union, 2011, European Commission, 2010b).

A 2014 study to determine the number of

countries with e-GIFs, identified at least 46 national

e-GIFs (Lisboa and Soares, 2014). The United

Kingdom (UK) e-GIF of 2000 is generally regarded

the first e-GIF published. The current Version 6.1

(e-Government Unit, 2006) covers the exchange of

information between the UK Government and

citizens, government organisations, intermediaries,

businesses (worldwide), etc. Even though e-GIFs are

considered important instruments to facilitate

interoperability of public systems, many national e-

GIFs was developed due to political pressures from

the European Commission, the United Nations and

the World Bank (IDABC, 2004, European Union,

2011, European Commission, 2010b, European

Commission, 2010a, United Nations Development

Programme, 2007, Lallana, 2008, The World Bank,

2012).

In September 2016, the South African

Government published a White Paper on the

National Integrated ICT Policy for the country

(Department of Telecommunications and Postal

Services, 2016). Amongst others, the White Paper

highlights some principles for e-Government. A

Digital Transformation Committee will oversee the

development of a detailed integrated national e-

Government strategy and roadmap.

To address part of the delivery infrastructure

principles identified in the White Paper, this paper

addresses one of the elements of such a strategy, by

proposing a baseline conceptual model for an e-GIF

for South Africa. We argue that best practices and

lessons learnt from previous attempts to the design

and development national and regional e-GIFs and

interoperable systems, combined with South African

legislation and past initiatives, could form a solid

grounding for the design of such a model.

Section 2 of this paper provides background by

describing the South African context in relation to

the use of ICT in government, and examples of

existing interoperability frameworks (national and

international) that can be used as guidance. Section 3

presents the proposed baseline conceptual model

derived for an e-Government interoperability

framework, including aims, principles, levels of

interoperability, a proposed conceptual framework

for e-GIF implementation and interoperability

governance. Section 4 concludes.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 The South African Context

The Public Administration and Management Act of

2014 (Republic of South Africa, 2014) provides for

the use of ICTs in the public administration,

including the requirement to ensure interoperability

of information systems across government. The

Electronic Communications Transactions Act of

2002 (Republic of South Africa, 2002a) sets out

provisions to enable and facilitate electronic

communications and transactions in the public

interest. The Act stipulates that the Department of

Telecommunications and Postal Services should

finalise an e-strategy. As a step in the process to

develop such a strategy, the South African

Government published a White Paper on the

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

494

National Integrated ICT Policy for the country

(Department of Telecommunications and Postal

Services, 2016) in September 2016. ICT is

considered as a means to facilitate inclusive socio-

economic transformation for South Africa. The

document highlights the uneven and often poor

quality of public services, as identified in the

National Development Plan (NDP) (National

Planning Commission, 2012). The White Paper

argues that digital transformation of government can

assist in transforming the public sector, increase

service delivery and ensure equitable access to all

public services. Making the most of the potential

role ICT can play in supporting radical

transformation, as envisaged in the NDP, will

require complex coordination and leadership across

government. Digital services is to be provided over

open access networks and a net neutrality regime to

protect and uphold open, inhibited access to legal

online content.

The White Paper defines e-Government as the

innovative use of ICTs (including mobile devices,

websites and other ICT applications and services) to

link citizens and the public sector, with the aim to

facilitate collaborative and efficient governance,

improve the efficiency of government processes,

strengthen public service delivery and enhance

participation of citizens in governance. The White

Paper also highlights some principles for e-

Government (see section 3). In addition, it highlights

the fact that the South African Government currently

has different information management initiatives in

place, which are not effectively connected to each

other and not necessarily interoperable. The need for

centralised coordination to ensure interoperability is

identified. A Digital Transformation Committee is to

oversee the development of a detailed integrated

national e-Government strategy and roadmap. The

roll-out plan is to include government-to-citizen,

citizen-to-government, government-to-government

and government-to-business programmes

(Department of Telecommunications and Postal

Services, 2016).

2.2 Interoperability Frameworks

As mentioned in section 1, a substantial number of

e-GIFs exist internationally. Examples include

Europe (European Commission, 2010b), Australia

(Department of Finance and Administration, 2006),

United Kingdom (e-Government Unit, 2006), New

Zealand (E-Government Unit, 2002), Philippines

(iGov Philippines, 2016b), and Ghana (National

Information Technology Agency, 2010).

The conceptual model for the interoperability

framework for South Africa proposed in this paper,

in the main, took guidance from the European

Interoperability Framework (European Commission,

2010b), the Philippine Electronic Government

Interoperability Framework (iGov Philippines,

2016b), the Australian Interoperability Frameworks

(Australian Government, 2005, Australian

Government, 2006, Australian Government, 2007),

and two South African interoperability frameworks,

namely the Minimum Interoperability Standards

(MIOS) for Government Information Systems

(Department of Public Services and Administration,

2011) and the National Health Normative Standards

Framework for Interoperability in eHealth (HNSF)

(National Department of Health, 2014). These

frameworks are briefly discussed below.

2.2.1 European Interoperability Framework

The European Commission has set out a common

coherent approach to interoperability for the EU and

Member States through the European

Interoperability Strategy (EIS) and the European

Interoperability Framework (EIF) (European

Commission, 2010a, European Commission, 2010c,

European Commission, 2010b).

The EIF aims to promote and support the

delivery of European public services by fostering

cross-sectoral and cross-border interoperability,

guide public administrations to provide European

public services to businesses and citizens, and tie

together and complement national interoperability

frameworks at European level. To achieve these

aims, the EIF sets out guidelines, including

underlying principles, a conceptual model for public

services, different levels of interoperability, the

concept of interoperability agreements, and the

governance of interoperability (European Union,

2011).

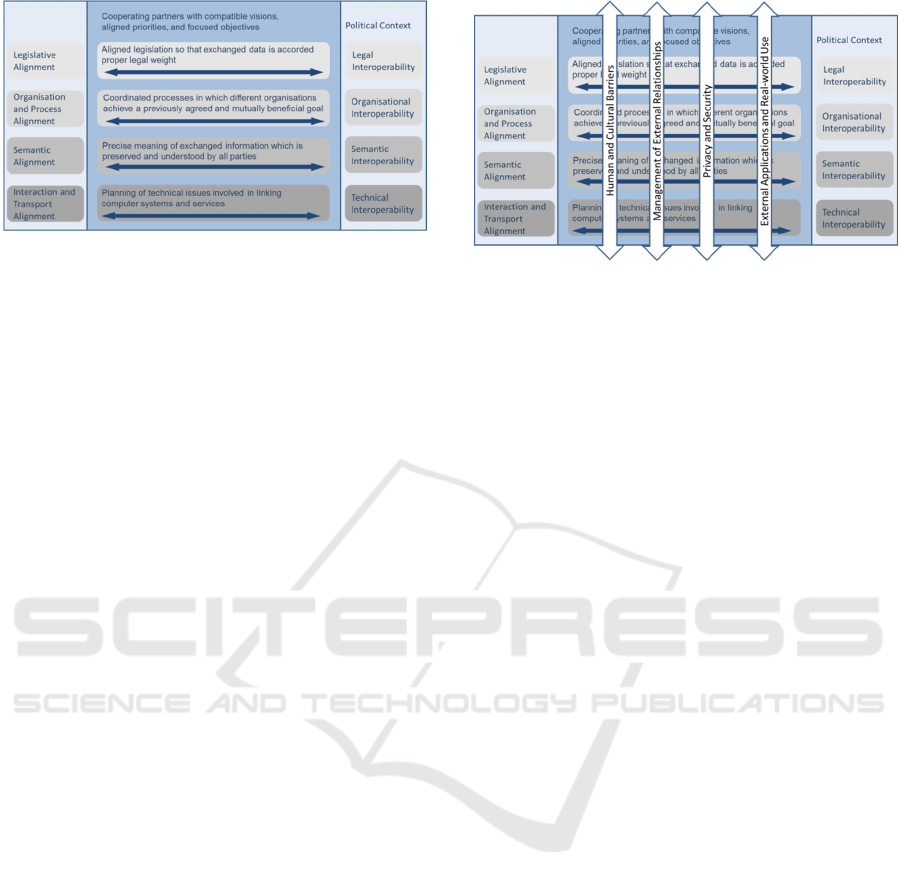

The EIF conceptual model consists of three

layers: the aggregate services layer, the secure data

exchange layer and the basic public services layer.

The practical implementation of the conceptual

model for cross border/sectorial services requires

considering the political context and four levels of

interoperability, as illustrated in Figure 1: legal,

organisational, semantic and technical

interoperability (European Union, 2011).

Some of our earlier work (Kotzé and Neaga,

2010, Kotzé, 2012) considered an early version of

the EIF and identified socio-technical aspects (e.g.

human and cultural barriers, management of external

relationships, privacy and security, and external

applications and real-world use) that might impact

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

495

Figure 1: Levels of Interoperability (figure adapted from

European Commission (2010b)).

all of the interoperability layers identified in the EIF,

as illustrated in

Figure 2

.

2.2.2 Philippine Electronic Government

Interoperability Framework

The Philippine Electronic Government

Interoperability Framework (PeGIF) addresses the

technical issues in using and operating resources,

issues related to the interaction of organisations, the

means of data exchange, rules and agreements for

sharing information and knowledge, and policies

related to the interaction among government

agencies, citizens and businesses. The PeGIF

addresses three domains (technical, information and

business process) and two crosscutting aspects

(security and best practice) (iGov Philippines,

2016b).

2.2.3 Australian Government

Interoperability Framework

The Australian Government Interoperability

Framework addresses the information, business

process and technical dimensions of interoperability

by setting the principles, standards and

methodologies that support the delivery of integrated

and seamless services, whole-of-government

collaboration and maximise opportunities for

exchange and reuse of information (Australian

Government, 2008). The Framework consists of

three layers, each with their own sub-framework:

• The business layer (Business Process

Interoperability Framework) comprises legal,

commercial, business and political concerns

(Australian Government, 2007).

• The information layer (Information

Interoperability Framework) comprises

information and process elements that convey

business meaning (Australian Government,

2006).

Figure 2: Socio-technical aspects impacting an

interoperability framework (adapted from (European

Commission, 2010b, Kotzé and Neaga, 2010, Kotzé,

2012)).

• The technical layer (Technical Interoperability

Framework) comprises technology standards

such as transport protocols, messaging

protocols, security standards, registry and

discovery standards, XML syntax libraries and

service and process description languages

(Australian Government, 2005).

2.2.4 South African Interoperability

Frameworks

2.2.4.1 Generic Framework - Mios

The State Information Technology Agency (SITA)

Act of 1998, amended in 2002 (Republic of South

Africa, 2002b), mandated SITA to set standards for

interoperability between information systems in

government and to certify information technology

goods and services for compliance against such

standards. Therefore, prior to the publication of the

White Paper on the National Integrated ICT Policy

for the country (Department of Telecommunications

and Postal Services, 2016), the Minimum

Interoperability Standards (MIOS) for Government

Information Systems document (Department of

Public Services and Administration, 2011),

developed by SITA, prescribed the open system

standards to be followed to ensure a minimum level

of interoperability within and between information

systems utilised in government, industry, citizens

and the international community in support of the

South African e-Government objectives.

2.2.4.2 Specialised Framework – HNSF

The National Health Normative Standards

Framework for Interoperability in eHealth (HNSF)

(National Department of Health, 2014) was

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

496

promulgated in 2014 as an extension to the National

Health Act of 2004 (Republic of South Africa,

2004). The HNSF sets the framework for eHealth

interoperability, and specify a standards-based

health information exchange and an enterprise

architecture as central to the implementation of

interoperability going forward for the healthcare in

the public sector. It also creates an obligation for the

National Department of Health to create a National

Health Standards Authority, which would set the

different interoperability and content standards for

eHealth in South Africa. The HNSF specifies

implementation guidelines to ensure interoperability

based on Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE)

Profiles (IHE International, 2015).

3 PROPOSED CONCEPTUAL

e-GIF MODEL

In the White Paper on the National Integrated ICT

Policy, the following principles are envisaged for all

digital government solutions (Department of

Telecommunications and Postal Services, 2016):

• Services:

Services must be designed for users / citizens,

including those with limited digital skills or

access to devices.

Mechanisms for monitoring of delivery of

services should be incorporated.

Online end-to-end public sector services

should be made available.

Cost-effective solutions for both users and

government should be explored.

• Delivery infrastructure:

Services should be offered in both an online

and offline mode.

Digital services should be based on open

standards and accessible on all devices and

platforms.

Personal information should be protected.

Citizens must all be provided with digital

addresses / identities to allow government to

engage with them directly.

Centralised coordination to ensure

interoperability is required.

Based on the South African context, the

principles envisaged in the White Paper and the

existing international and national e-GIFs, we

propose a conceptual model that could be considered

as baseline for the development of a South African

e-GIF. Such an e-GIF should be aimed at data and

information exchange between government sectors,

government and citizen, and government and

businesses. The proposed e-GIF conceptual model is

an enterprise model on an abstraction level suitable

for strategic planning.

The model is complementary to the MIOS

(Department of Public Services and Administration,

2011) in that it provides for an ‘environment’ or

‘enterprise context’ in which the MIOS can be

applied. The e-GIF could be enhanced with sectoral

e-GIFs (e.g. for health, finance, social services, etc.)

to address specific needs of a sector, but such

sectoral e-GIFs should adhere to the baseline

provisions and principles of the overarching e-GIF

accepted. The National Health Normative Standards

Framework for Interoperability in eHealth (HNSF)

(National Department of Health, 2014) is an

example of such an sectoral e-GIF, and also address

interaction with non-governmental institutions.

3.1 Aims of the Proposed e-GIF Model

The proposed e-GIF conceptual model is aimed at

achieving (iGov Philippines, 2016c, Department of

Public Services and Administration, 2011):

• Seamless flow of information across

government.

• Increased productivity of government

service delivery operations.

• Increased efficiency of government

services.

• Improved decision-making in

government.

• Reduced cost and increased savings for

government.

• Digital inclusion.

• Increased citizen satisfaction in

transacting with government.

• Enhanced ability to interoperate with

other countries across national

boundaries.

• Better informed and active citizenry.

• Improved ecosystem for competition and

innovation among ICT service providers.

3.2 Principles for e-GIF Development

The following generic principles / drivers are

proposed to guide the development of the e-GIF

(United Nations Development Programme, 2007,

European Commission, 2010b, European Union,

2011, iGov Philippines, 2016b, Lallana, 2008, e-

Government Unit, 2006, Jaeger, 2003, German

Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2008):

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

497

• User-centricity: Supporting the needs of

citizens and businesses in a secure and

flexible manner.

• Administrative simplification: Alleviating

the burden on businesses and citizens for

compliance to legal obligations by

providing integrated services.

• Inclusion and accessibility: Equal

opportunities should be created for access

to public services through open and

inclusive services, on all devices and

platforms, to all citizens without

discrimination, including persons with a

disability and the elderly.

• Multilingualism: Information systems for

the public service should support

multilingualism in support of the National

Language Policy Framework as it applies

to all government structures (Department

of Arts and Culture, 2003).

• Interoperability: Guaranteeing a media-

consistent flow of information between

citizens, business and government.

• Scalability: Ensuring the adaptability,

usability and responsiveness of

applications and requirements as change

and demands fluctuate.

• Reusability: Solutions should be

developed to facilitate sharing and re-use.

This include defining data structures,

establishing processes and standards for

similar procedures for providing services,

considering the solutions of exchange

partners, etc.

• Openness: Focus on using open-standards

that are vendor and product neutral and

based on the principle of shared

knowledge.

• Market support: Drawing on established

standards already widely used and

recognised in industry.

• Neutrality and adaptability: Specific or

restricted technology should not be

imposed on citizens, businesses or other

administrations.

• Security: Ensuring a reliable exchange of

information conforming to an established

security policy.

• Privacy: Guaranteeing the privacy and

confidentiality of information related to

citizens, businesses and government

organisations and ensuring personal data

protection.

• Transparency: Citizens and businesses

should be able understand and respond to

the administrative processes that affect

them and make suggestions for

improvement.

• Effectiveness: Solutions should be aimed

at serving citizens and business and make

the best use of taxpayers money.

• Forward-looking: The wider-

encompassing national e-Government

strategy or vision, values, principles and

policy directions of government should be

supported.

• Open standards: Preference should be

given to the use of open international and

national standards with the broadest

remit.

•

Technology neutrality: Services should be

provided through interfaces that are

technology and vendor agnostic.

3.3 Levels of Interoperability

Interoperability is often thought of in terms of ICT

systems exchanging information. e-Government

interoperability is, however, much more than just

smart middleware (enabling interoperability on a

technical level) (Scholl, 2005). Political, legal,

organisational and social aspects are fundamental to

e-Government success and therefore requires careful

consideration in any e-GIF. Efforts to practice

effective information sharing have to be aware of

intentionally imposed (constitutional and legal)

barriers, organisational impediments, technology

obstacles and a wide variety of stakeholder concerns

about policies, the processes, the procedures and the

extent of sharing information between government

entities and other agencies (Scholl, 2005). To

support this notion, levels of interoperability

consisting of political, legal, organisational,

semantic, syntactic and technical interoperability, as

proposed by the European Interoperability

Framework (European Commission, 2010b) and

illustrated in Figure 1, are used and applied to the

South Africa context.

3.3.1 Political Context

Shared information would allow for better

coordination of government entity programmes and

services, as well as improved accountability (Scholl,

2005), but this may require the buy-in of various

political entities that do not necessary share the same

vision, values or underlying doctrine. Government

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

498

entities may have entrenched cultures that do not

value openness and cooperation with other entities,

and which may make it hard for them to trust and

share information.

The federated nature of the South African

political and legislative context should be taken into

consideration. Although legislation is often

promulgated at national level, implementation takes

place at national, provincial and local government

level (South African Government, 2016).

Information about / for citizens is often gathered at

local government level, which may be governed by a

different political party than that of provincial or

national government. Specific provincial and local

government policies and regulations also exist and

may apply. Although many government entities

prefer (or is forced by legislation) to operate

independently, cooperation between all three spheres

of government is required for successful e-

Government programmes. Cross-functional

collaboration is key to e-Government projects

(Corydon et al., 2016). A lack of coordination and

cooperation between different levels of government

can have a significant impact on the success of e-

Government efforts (Kuk, 2003, Jaeger and

Thompson, 2003).

For example, on national level, the Department

of Home Affairs (DHA) is the custodian of the

national identification system, but sharing of the

information captured in the system with other

national departments (for example the National

Department of Health), or provincial or local

government systems (for example for the issuing of

drivers licences), would be required. If this is not

possible, or is not allowed by DHA or the legal or

constitutional barriers it is bound by, it may lead to

the development of parallel identity management

systems that may be inconsistent, not compatible

and not interoperable. For example, the Health

Population Registration Systems (HPRS) is currently

under development by the National Department of

Health (Wolmarans et al., 2015), but is implemented

at provincial and local government level. Although

the system makes use of the national identity

number for identification, it is not able to link

directly to the DHA system yet, but will be able to

do so in future. HPRS generates a unique patient

record number that can be used by various electronic

medical record (EMR) systems already

implemented. HPRS can also record the patient

record numbers used by these EMR systems, but

legacy inconsistencies in patient demographics may

still be encountered across EMRs.

A policy review process has identified the need

for the finalisation of a national framework for

digital verification that will ensure that Government

adopts at least one system to ensure integrity and the

ease of use of identity verification mechanisms

(Department of Telecommunications and Postal

Services, 2016). For e-Government to be successful

and of value to both government and citizens, the

same kind of review process may be required for the

many other aspects that may impede on political

interoperability.

3.3.2 Legal Interoperability

As mentioned above, each government

administration, whether national, provincial or local,

contributing to digital government solutions may

work within its own legal framework or jurisdiction.

Sometimes incompatibilities between these different

spheres of government may make the sharing of

information complex or even impossible. New legal

initiatives may be required to overcome such a

situation. Public administrations should therefore

carefully consider all the relevant legislation related

to data exchange, data protection, privacy, etc. when

planning to establish e-Government solutions

(European Commission, 2010b).

Legal interoperability has to do with addressing

aspects related to defining, achieving and

maintaining authenticity, integrity, confidentiality,

accountability, availability, non-repudiation and

reliability (iGov Philippines, 2016a).

For example, a range of laws and policies have

already been promulgated to protect South African

citizens both online and offline. In the context of the

proposed e-GIF model, examples include:

• The Protection of Personal Information

Act of 2013 (Republic of South Africa,

2013) that sets out provisions to protect

personal data and requirements on how

such data is exchanged, stored and

collected.

• The Electronic Communications

Transactions Act of 2002 (Republic of

South Africa, 2002a) that sets out

provisions to enable and facilitate

electronic communications and

transactions in the public interest, and

also the framework for electronic

signature verification and the

accreditation of electronic signature

providers.

• The Consumer Protection Act of 2008

(Republic of South Africa, 2008),

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

499

especially in the case where payment has

to be made to obtain a document or for

services provided.

• The National Cybersecurity Policy

Framework (State Security Agency,

2015) that is intended to promote and

ensure a comprehensive legal framework

governing the cyberspace, and aims to

implement an all-encompassing approach

pertaining to all the role players

(government, public, private sector, civil

society and special interest groups) in

relation to cybersecurity.

• The draft Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity

Bill (Department of Justice and

Constitutional Development, 2015) that

aims to put in place measures to

effectively deal with cybercrimes, e.g.

identity theft and other online crime, and

address aspects relating to cybersecurity

that may adversely affect individuals,

businesses and government alike.

• The Film and Publications Board Act of

2014 (Film and Publication Boad, 2014)

setting out provisions for the

classification of content and the

protection of children.

Some of this legislation may be contradictory

and even prohibit or limit government entities from

exchanging information, and consequently restrict

interoperability and participation in cooperative

activities. Such legislation may require alignment.

3.3.3 Organisational Interoperability

Organisational interoperability (also called business-

process interoperability in some e-GIFs) is about

addressing the common methods, processes, and

shared services for collaboration, including

workflow, business transactions and decision-

making (iGov Philippines, 2016a, Australian

Government, 2005, Australian Government, 2007).

In e-Government this aspect has to do with how

government organisations cooperate amongst

themselves and with citizens and civil society to

achieve mutually agreed goals. Organisational

interoperability in the context of e-Government

therefore has to do with the coordination and

alignment of business processes and information

architectures, spanning both intra and inter-

government organisational boundaries, with the aim

to exchange information (United Nations

Development Programme, 2007).

As stated in section 3.3.1, a lack of coordination

and cooperation between different levels of

government, or different government entities on the

same level of government, can have a significant

impact on the success of e-Government efforts (Kuk,

2003, Jaeger and Thompson, 2003). To overcome /

prevent this problem may require the integration or

alignment of business processes to be able to work

together efficiently and effectively, or even to define

and establish new business processes made possible

by an interoperable e-Government infrastructure

(European Commission, 2010b). It will also require

the clear structuring of relationship between service

providers (government organisations) and service

consumers (citizens, businesses and other

government organisations) and other stakeholders.

The basic principle is that those who can affect or

will be affected by e-Government initiatives should

be accounted for (Jaeger, 2003).

In a democratic system of government based on a

division of power and distributed control, such as

South Africa, inter-organisational collaboration rests

on the own interest of the parties involved and their

willingness to collaborate, the resources at their

disposal and the expected benefits / outcomes of e-

Government initiatives (Scholl, 2005). Change

management processes will therefore be critical in

order to ensure continuity of services, reliability and

the buy-in of all parties involved.

3.3.4 Semantic and Syntactic

Interoperability

Semantic and syntactic interoperability, also referred

to as information interoperability in some existing e-

GIFs, refer to the ability to transfer and use

information in a uniform and efficient manner across

multiple government entities and ICT systems

(Australian Government, 2006). Semantic

interoperability is about addressing a common

methodology, definition and structure of

information, along with shared services for its

retrieval (iGov Philippines, 2016a). It addresses the

meaning of data elements and the relationship

between them. Syntactic interoperability is about

describing the exact format of the information

(European Commission, 2010b). Semantic

interoperability enables participants in e-

Government initiatives to process information from

other resources in a meaningful manner and ensures

that the precise meaning of exchanged information is

understood and preserved throughout. Sector-

specific and cross-sectoral data structures and data

element sets with agreed meaning, commonly

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

500

referred to as semantic interoperability assets, should

be created and shared for use by cooperating

organisations.

Multilingualism should also be addressed at this

level (European Commission, 2010b). The multi-

cultural and multi-lingual context in South Africa

with its 11 official languages (South African

Government, 2016), requires a careful consideration

at semantic and syntactic interoperability level.

3.3.5 Technical Interoperability

Technical interoperability is about addressing the

linking of ICT systems and services, including

interfaces, interconnection, data integration, data

exchange, security and presentation (iGov

Philippines, 2016c, Australian Government, 2005).

Technical interoperability requires formalised

standards-based specifications for interfaces,

interconnection services, data integration services,

content management and metadata, information

access and presentation, information exchange,

security, web-based services, etc. While different

government organisations might have specific

characteristics at political, legal, organisational and,

to some extent, semantic level, it is not the case at

technical level where formalised specifications must

be adhered to (European Commission, 2010b,

United Nations Development Programme, 2007).

The selection of specific standards to be included

should be based on the following principles

(Department of Public Services and Administration,

2011, iGov Philippines, 2016b, United Nations

Development Programme, 2007):

• Standards that enhance data / information

exchange: Standards that are relevant to

systems’ interconnectivity, data

integration, presentation and interface, e-

services access, and content management

metadata.

• Promote openness: The use of open

standards, as opposed to proprietary

standards, and specifications that

contribute to open systems is encouraged.

This is in line with the ethos of the MIOS

(Department of Public Services and

Administration, 2011).

• Conform to international best practices:

Preference should be given to established

standards with the widest applicability.

Widely adopted international standards

localised to fit the South African context

should be the preferred option. Regional

and national standards should only be

developed if no appropriate international

standards exist.

• Scalability: The standards should be able

to satisfy increased demands on capacity,

such as changes in data volumes, number

of transactions or number of users.

• Have existing market base: The standards

selected should be widely supported by

the industry, to ensure a reduction in cost

and risk for the e-Government systems.

Overall it is about best practice: Addressing

aspects related to demonstrating the best uses of

standards in the public and private sectors to achieve

technical, semantic, syntactic, organisational, legal

and political interoperability (iGov Philippines,

2016c, United Nations Development Programme,

2007).

3.4 Conceptual Framework for e-GIF

Implementation

Based on the various aims, principles and levels of

interoperability required, a conceptual framework

for the implementation of an e-GIF to support

interoperable e-Government in South Africa is

proposed. Each of the key components of the

framework, as illustrated in Figure 3, is briefly

introduced in the sections below.

3.4.1.1 Basic e-Government Services

The top layer refers to the basic government services

and registries. Delivering services to citizens is at

the core of what most government entities do, or is

supposed to do, and is critical in shaping trust in and

perceptions of the public sector. Tasks like paying

taxes, renewing drivers licenses, and applying for

social benefits are often the most tangible

interactions citizens have with their government

(Dudley et al., 2016). Following a citizen-centric

approach to services design and delivery is at the

centre of successful e-Government. This is in

contrast to the development of services based on the

government entity’s own requirements and processes

(Dudley et al., 2016).

As a minimum, base registries are required to

uniquely identify individuals and organisations (e.g.

government departments, businesses, etc.) (National

Department of Health, 2014, European Commission,

2010b). Base registries are under the legal control of

public administrations and maintained by them.

The digital identity registry may, for example, be

owned and controlled by DHA, but shared with

other services providers, enabling unique and

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

501

consistent identification of individuals across all e-

Government services. The digital identity registry

may contain identity numbers (or passport numbers),

digital addresses, names, surnames and other

demographic information related to individuals. The

same type of information will be required for

organisations. An example of other possible

registries is the vehicle registry containing vehicle

register numbers, vehicle identification numbers and

other identifying information for a particular vehicle

(for example, an interoperable implementation of the

identification register for eNaTiS (2011)).

The data repositories contain the repositories of

services and data offered by various agencies and

government departments (National Department of

Health, 2014). These services and data can only be

accessed and updated by accredited consumer

applications through the secure data exchange layer.

Figure 3: Conceptual e-GIF implementation framework for South Africa.

Data services may also include services provided by

external parties, for example payment services

provided by financial institutions and connectivity

services provided by telecommunication providers.

Designing basic e-Government services,

however, involves considerably more than merely

designing the technical / ICT systems to offer the

services. Each service will have to consider, and

take cognisance of, the various political, legal and

organisational aspects that might affect the design

and delivery of a service across various government

entities and within the boundaries of relevant

legislation that applies, as indicated in section 3.3.

3.4.1.2 Secure Data Exchange and Security

Layer

The secure data exchange layer is central to the e-

Government conceptual model and implementation

framework since all access to e-Government

services passes through it. It allows for a secure

exchange of certified messages, records, forms and

other kinds of information between different

systems. This layer also handles specific security

requirements such as electronic signatures,

certification, encryption and time stamping. The

security and audit services cut across all technical

interoperability layers. The secure data exchange

layer should therefore be a secure, managed,

harmonised and controlled layer, allowing data

exchanges between government administrations,

citizen and business that are (United Nations

Development Programme, 2007, European

Commission, 2010b, Department of Public Services

and Administration, 2011):

• Signed and certified: Both the sender and

receiver must be identified and

authenticated through agreed

mechanisms.

• Encrypted: The confidentiality of the data

exchanged must be ensured.

• Logged: All electronic transactions are

logged and archived to ensure a legal

audit trial.

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

502

Some of the technical elements incorporated in

this layer are (United Nations Development

Programme, 2007, European Commission, 2010b,

National Department of Health, 2014, German

Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2008):

• Interoperability facilitators: Providing

services such as translation of protocols,

formats and languages and acting as

information brokers. Effective e-

Government in a multi-lingual society

requires standardization of spellings,

word use, and support for languages in

which citizens are comfortable

communicating.

• Content management services: Pertaining

to (open) standards for retrieving and

managing government information.

• Data integration services: Containing

(open) standards for the description of

data that enable data exchange between

disparate systems.

• Standards based interfaces or

interconnection: Enabling the

communication between systems through

consistent interfaces.

• Orchestration: The process that involves

the invocation of the appropriate services

and the manipulation of data according to

agreed workflows and supporting

organisational (business) processes.

Consumer applications usually access the data

exchange and security layer through middleware

services, for example replication, distributed

transaction management, personalization,

internationalization, messaging, etc. (German

Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2008).

3.4.1.3 Consumer Applications

Consumer applications refer to the various e-

Government applications used to access the services

and data through the secure data exchange layer. The

key to good e-Government services is understanding

the user’s perspective. The applications can be

unique to a specific government department, or

aggregated. Aggregated applications appears to a

user as a single service, but are constructed by

grouping a number of public services according to

certain specific business requirements.

The German SAGA document (German Federal

Ministry of the Interior, 2008), as example, provides

guidelines for client applications, which make use of

a service offered by middleware, barrier-free

presentation, etc.

3.4.1.4 End-user Devices

End-user devices refer to the various electronic

channels that can be used by citizens, business and

government employees to access the e-Government

services or data, or provide data towards the

repositories. The White Paper on the National

Integrated ICT Policy, applicable to all digital

government solutions (Department of

Telecommunications and Postal Services, 2016),

calls for both online and offline access to

government services, and access to services desks

for human-human interaction should therefore also

be catered for.

In alignment with citizen’s digital preferences

and behaviours, there is currently a worldwide move

to providing services on mobile platforms and

through the use of smart devices (Corydon et al.,

2016, Thomas and Rosewell, 2016). With the

proliferation of mobile and smart device use in

South Africa, opportunities provided by all-round

mobility and internet of things (IoT) devices /

applications should be seized, but without

marginalising citizens that do not have access to

such technology.

3.5 Interoperability Governance

The final element required in any e-GIF model is

governance. The implementation of any e-GIF

requires proper governance and continuous

interoperability maintenance to keep the e-GIF up to

date and relevant. Interoperability governance is also

about ensuring the e-GIFs proper implementation

(United Nations Development Programme, 2007),

and would require the establishment of one or more

agencies to specifically deal with certain aspects of

the implementation of the e-GIF across

administrative levels. Such an agency should be

(United Nations Development Programme, 2007,

Lallana, 2008, European Commission, 2010b,

National Department of Health, 2014, German

Federal Ministry of the Interior, 2008):

• Primarily focus on standardising and

ensuring interoperability on a national,

provincial and/or local government level,

as appropriate.

• Separate from the sectoral domains to

ensure independence and impartiality.

• Capable of working as a collaboration

partner with the sectors.

• Seen as experts in the field of

interoperability and government services

to engender trust.

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

503

• Capable in the selection of appropriate

standards.

• Capable of guiding the development of

implementation guidelines based on the

selected standards to ensure

interoperability.

• Pro-active in the proclamation and

promotion of standards and their use.

• Responsible for monitoring the use of

standards and the adherence to standards,

policies and guidelines.

• Acting as an advisory body in developing

strategies and implementing solutions,

coordinating cross-agency aggregated

services, and to community of practice in

setting and publishing standards.

• Acting as accreditation authority for

certifying consumer applications that

access and update the data repositories in

order to provide e-Government services.

The German SAGA document (German Federal

Ministry of the Interior, 2008), as example, provides

an in-depth overview of how interoperability

governance can be approached.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Enterprise modelling, in general, provides a

structured and diagrammatic “framework for

depicting the myriad interconnected and changing

components addressed in large scale change”

(Whitman and Gibson, 1996: 64). This paper

proposed a conceptual model for the development of

an e-GIF for South Africa that can serve as guideline

in drafting enterprise models for enterprises

involved in, and moving towards, e-Government

activities. The model suggests what enterprise

models have to deal with to ensure enterprise

interoperability in e-Government. To implement the

proposed conceptual model, the various components

must be modelled and populated by defining or

developing policies, guidelines, principles,

standards, vocabularies, concepts, recommendations,

etc. To ensure interoperability and consistency, it is

also recommended that implementation guidelines

be developed, similar in nature to the IHE profiles

(IHE International, 2015) used in e-Health. It is also

recommended that an agency be established to guide

and govern the implementation of an e-GIF across

various regional, provincial and national contexts,

and coordinate the integration of information

required on national (or provincial or local level).

REFERENCES

Australian Government. (2005). Australian Government

Technical Interoperability Framework. Australian

Government Information Management Office.

Australian Government. (2006). The Australian

Government Information Interoperability Framework.

Australian Government Information Management

Office.

Australian Government. (2007). The Australian

Government Business Process Interoperability

Framework. Australian Government Information

Management Office.

Australian Government. (2008). Interoperability

Frameworks. Department of Finance. Available:

http://www.finance.gov.au/archive/policy-guides-

procurement/interoperability-frameworks/ [Accessed

24 January 2016].

Corydon, B., Ganesan, V. & Lundqvist, M. (2016).

Transforming Government Through Digitization.

Public Sector. McKinsey & Company.

Department of Arts and Culture. (2003). National

Language Policy Framework. South Africa.

Department of Finance and Administration. (2006).

Delivering Australian Government Services: Access

and Distribution Strategy, Canberra, Australian

Government.

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development.

(2015). Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity Bill. South

Africa.

Department of Public Services and Administration.

(2011). Minimum Interoperability Standards (MIOS)

for Government Information Systems Revision 5.0.

Pretoria: State Information Technology A and gency:

Standards and Certification Unit Government

Information Technology Officer Council.

Department of Telecommunications and Postal Services.

(2016). National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper.

South Africa.

Department of Transport. (2011). eNaTiS. Available:

http://www.enatis.com/ [Accessed 3 February 2017].

Dudley, E., Lin, D.-Y., Mancini, M. & Ng, J. (2016).

Implementing a Citizen-centric Approach to

Delivering Government Services. Public Sector.

McKinsey & Company.

E-Government Unit. (2002). A New Zealand

e_Government Interoperability Framework (e-GIF).

The New Zealand Government State Services

Commission.

e-Government Unit. (2006). e-Government

Interoperability Framework Vesion 6.1, London,

Cabinet Office.

European Commission. (2010a). Communication from the

Commission to the European Parliament, the Council,

the European Economic and Social Committee and the

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

504

Commttee of the Regions: Towards interoperability

for European public services. Brussels.

European Commission. (2010b). European Interoperability

Framework (EIF) for European public services.

Communication from the Commission to the European

Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and

Social Committee and the Commttee of the Regions:

Towards interoperability for European public services

- Annex 2. Brussels.

European Commission. (2010c). European Interoperability

Strategy (EIS) for European public services.

Communication from the Commission to the European

Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and

Social Committee and the Commttee of the Regions:

Towards interoperability for European public services

- Annex 1. Brussels.

European Commission. (2017). eGovernment & Digital

Public Services Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-

single-market/en/public-services-egovernment

[Accessed 17 January 2017].

European Union. (2011). European Interoperability

Framework (EIF): Towards Interoperability for

European Public Services, Luxembourg, Publications

Office of the European Union.

Film and Publication Boad. (2014). Classification

Guidelines for the Classification of Films, Interactive

Computer Games and Certain Publications. South

Africa.

Frank, U. (2009). Enterprise Modelling. Universität

Duisburg-Essen - Information Systems and Enterprise

Modelling Available: https://www.wi-inf.uni-

due.de/FGFrank/index.php?lang=en&&groupId=1&&

contentType=ResearchInterest&&topicId=14

[Accessed 3 March 2017].

German Federal Ministry of the Interior. (2008). SAGA:

Standards and Architectures for eGovernment

Applications Version 4.0.

IDABC. (2004). Europen Interoperability Framework for

Pan-European eGovernment Services Version 1.0,

luxemborg, European Commission.

iGov Philippines. (2016a). Information Interoperability

Framework (PeGIF Part 2). Available:

http://i.gov.ph/policies/information-interoperability-

framework/ [Accessed 19 December 2016].

iGov Philippines. (2016b). Philippine eGovernment

Interoperability Framework (PeGIF). Available:

http://i.gov.ph/pegif/ [Accessed 19 December 2016].

iGov Philippines. (2016c). Technical Interoperability

Framework. Available:

http://i.gov.ph/policies/technical-interoperability-

framework/ [Accessed 19 December 2016].

IHE International. (2015). IHE Profiles. Integrating the

Healthcare Enterprise. Available:

http://www.ihe.net/profiles/index.cfm [Accessed 25

May 2016].

Jaeger, P. (2003). The endless wire: E-government as

global phenomenon. Government Information

Quaterly, 20, 323 - 331.

Jaeger, P. & Thompson, K. (2003). E-government around

the world: lessons, challenges, and future directions.

Government Information Quaterly, 20, 389 -394.

Kotzé, P. (2012). Keynote Address: Technical and Socio-

technical Approaches to Health Informatics in Africa.

IASTED Health Informatics 2012 Conference.

Gaborone, Botswana.

Kotzé, P. & Neaga, I. (2010). Towards an Enterprise

Interoperability Framework. In: Ly, L., Thom, L.,

Rindele-Ma, S., Gerber, A., Hinkelman, K., Kotzé, P.,

Reimer, U., Van Der Merwe, A., Mansoor, W.,

Elnaffar, S. & Monfort, V. (eds.) Proceedings of the

International Joint Workshop on Technologies for

Context-Aware Business Process Management,

Advanced Enterprise Architecture and Repositories

and Recent Trends in SOA Based Information Systems.

Portugal: SciTe Press.

Kuk, G. (2003). The digital divide and the quality of

electronic service delivery in local government in the

United Kingdom. Government Information Quaterly,

20, 353 - 363.

Lallana, E. (2008). e-Government Interoperability: Guide,

Bangkok, United Nations Development Programme.

Lisboa, A. & Soares, D. (2014). e-Government

interoperability frameworks: a worldwide inventory.

Procedia Technology, 16 (2014), 638 -648.

National Department of Health. (2014). National Health

Normative Standards Framework for Interoperability

in eHealth in South Africa, Version 2.0. Pretoria:

CSIR and NDoH.

National Information Technology Agency. (2010). Ghana

e-Government Interoperability Framework. Ghana.

Available:

http://www.nita.gov.gh/sites/default/files/resources/E

A%20&%20eGIF%20Main%20Doc/eGovernment%2

0Interoperability%20Framework.pdf [Accessed 19

December 2016].

National Planning Commission. (2012). National

Development Plan 2030: Our Future - Make it Work.

Pretoria: The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

Available:

http://www.poa.gov.za/news/Documents/NPC%20Nat

ional%20Development%20Plan%20Vision%202030%

20-lo-res.pdf [Accessed].

Republic of South Africa. (2002a). Electronic

Communications and Transactions Act. Government

Gazette Vol. 446, No. 23707, 2 August 2002.

Republic of South Africa. (2002b). State Information

Technology Agency Amendment Act, 2002.:

Government Gazette Vol. 449, No.24029, 7 November

2002.

Republic of South Africa. (2004). The National Health

Act, 2004. Government Gazette Vol.469, No. 26595,

23 July 2004.

Republic of South Africa. (2008). Consumer Protection

Act. Government Gazette Vol. 526, No. 321867, 29

April 2009.

Republic of South Africa. (2013). Protection of Personal

Information Act. Government Gazette Vol.581, No.

37067, 26 November 2013.

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

505

Republic of South Africa. (2014). Public Administration

Management Act. Government Gazette Vol. 594, No.

38374, 22 december 2014.

Scholl, H. (2005). Interoperability in e-Government: More

than Just Smart Middleware. Proceedings of the 38th

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences -

2005. IEEE.

South African Government. (2016). About SA. Available:

http://www.gov.za/about-sa [Accessed 23 January

2017].

State Security Agency. (2015). The National

Cybersecurity Policy Framework (NCPF). South

Africa.

Tadjeddine, K. & Lundqvist, M. (2016). Policy in the Data

Age: Data Enablement for the Common Good. Digital

McKinsey. McKinsey & Company.

The World Bank. (2012). Innovations in Retail Payments

Worldwide – A Snapshot. In: Payment Systems and

Policy Research (ed.) Financial Infrastructure Series.

Thomas, I. & Rosewell, D. (2016). The Four Essential

Pillars of Digital Transformation. RunMyProcess.

United Nations Development Programme. (2007). e-

Government Interoperability: Guide, Bangkok, United

Nations Development Programme.

Whitman, M. & Gibson, M. (1996). Enterprise modelling

for strategic support. Information Systems

Management, 13, 64-72.

Wolmarans, M., Tanna, G., Dombo, M., Prasons, A.,

Solomon, W., Chetty, M. & Venter, J. (2015). eHealth

Programme reference implementation in primary

health care facilities. South African Health Review,

2014/15, 35 - 43.

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

506