A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process

Management in Small Medium Enterprises

Dina Jacobs

1

, Paula Kotzé

2,3

and Alta van der Merwe

3

1

triVector, Centurion, South Africa

2

CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa

3

Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Keywords: Growth Stage Models, Growth State Transition Models, Small and Medium Enterprises, Business Process

Management.

Abstract: A key constraint for growing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in South Africa is the business skills

required to grow the enterprises through the stages of transformation. Business process management (BPM)

is one of the skills that could add value during transformation. Understanding the stages of transformation

during SME growth would assist to position BPM as an instrument of value for SMEs. These stages of SME

growth are typically defined as part of the SME growth stage models. However, criticism against SME

growth stage models is of concern. In this article, we propose the 5S SME Growth State Transition Model in

order to counteract some of the criticisms. The value contribution of the Model lies in defining typical states

associated with SME growth that can be used as input in research to position BPM as management approach

during SME growth.

1 INTRODUCTION

Growing small enterprises to become medium

enterprises, with the objective of job creation, is a

top priority in South Africa (DTI, 1995). However,

over and above resource poverty, a key constraint is

the business skills required to grow the small

enterprises through the various stages of

transformation. This lack of business skills as a

constraint, is confirmed from a global perspective by

Jones (2009) in his recommendation for training for

all small and medium enterprise (SME)

entrepreneurs to prepare them for their journey and

the challenges and crises that they will encounter

along the way. Hanks et al. (1993) also refer to the

lack of business skills and the formidable challenge

of guiding an organisation through the growth

process. In our wider research, on the possible use of

business process management (BPM) as a

management approach to assist SME managers, who

operate under the constraint of resources poverty,

through the transitions of growth, we again realised

the need to address the stage-state issue in SME

growth. Our view of BPM is guided by the Forrester

Research definition of BPM (Miers, 2011), which

positions BPM as a management approach,

including support of organisational change, value

optimisation and ongoing performance

improvement. We argue that the understanding of

the typical stages of transformation during SME

growth would assist to position BPM as suitable

management approach during SME growth. The

initial argument may be that there are consolidated

growth stage models available for SMEs to define

the typical stages of transformation. However, in a

review of relevant material on growth stage models

(Davidsson et al., 2005, Hanks et al., 1993, Jones,

2009, McMahon, 1998, Miller, 1987, Perenyi et al.,

2008, Jacobs et al., 2011), evidence was found that

this argument might be questionable, specifically

due to the status of such growth stage models for

SME’s. A review of the work done by , Davidsson

et al. (2005), McMahon (1998) and Hanks et al.

(1993), for example, revealed criticisms regarding

over-determinism and questionable empirical

support. Another of the critiques revealed, which is

addressed in this paper, is that the growth stage

models tend to assume that all SMEs pass

inexorably through each stage of the model.

In our earlier work, we investigated the

enhancement of growth stage models with enterprise

architecture principles, with the objective of

Jacobs, D., Kotzé, P. and Merwe, A.

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises.

DOI: 10.5220/0006385305070519

In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2017) - Volume 3, pages 507-519

ISBN: 978-989-758-249-3

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

507

providing guidance to SME managers during the

transformation process from being a small enterprise

to becoming a big enterprise (Jacobs et al., 2011).

One of the suggestions from this work was to

consider replacing the stage concept with a ‘current

to future state transition’ approach.

Following up on this suggestion, the focus of this

paper is the development of an SME growth state

transition model, called the 5S SME Growth State

Transition Model, aimed also at counteracting the

identified critique against growth stage models. The

intention is, as part of our wider research to position

BPM as management approach for SME growth, to

use this Model to enrich/adapt BPM approaches to

assist SME managers through transitions of growth.

The Model is not a proposed alternative for SME

growth stage models as such; its aim is specific to

identifying transitions as input towards our

mentioned research.

Section 2 describes the background to this paper

with reference to SME growth and SME growth

stage models. The research method is described in

section 3. Section 4 elaborates on the problems

identified with growth stage models for SMEs. The

proposed 5S SME Growth State Transition Model is

presented in section 5, with an overview of a

demonstration of the applicability of the 5S SME

Growth State Transition Model discussed in section

6. Section 7 concludes with a discussion of the value

of the 5S SME Growth State Transition Model and a

reference to future research.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 SME Growth

The definition of SMEs in South African legislation

makes provision for SME growth with reference to

micro, very small, small and medium enterprises. In

South Africa a small business is defined, per sector,

by the number of employees and/or turnover and/or

assets as defined in the National Small Business Act

of 1996 (DTI, 2008). As an example, the criteria for

a medium enterprise vary per sector from 100 to 200

employees, with a turnover of between R5 million

and R64 million, and assets with a value of between

R3 million and R23 million.

SME growth is associated with a change in status

of the SME through various transitions. The South

African Department of Trade and Industry (DTI)

defines the transition cycle associated with SME

growth from an informal to a formal business as: (1)

seed stage, (2) operational, (3) registration for VAT

(value added tax), (4) permanent employment, and

(5) registration as a legal entity (DTI, 2008).

2.2 SME Growth Stage Models

Davidsson et al. (2005) and McMahon (1998) refer

to the seminal book by Penrose (1959) explaining

the two different connotations of growth, namely the

amount of growth versus the process of growth.

SME growth stage models are related to the process

of growth. SME growth is viewed as a series of

phases or stages of development through which the

business may pass during an enterprise life cycle. In

their review of research on small firm growth,

Davidsson et al. (2005) define growth stage models

as a description of the distinct stages of SME

growth, as well as the set of typical problems and

organisational responses associated with each stage.

A large number of SME growth stage models exist.

The SME growth stage models that focus on

generic problems that organisations may encounter

during growth are valuable from various

perspectives:

• From a management perspective, for the

definition of SME operating models and helping

SME managers to make important decisions

(Jones, 2009).

• From the prediction perspective, one of the

objectives of the model by Greiner (1972) is to

create awareness among entrepreneurs of

possible crises and solutions as part of the

transformation through the different stages.

• From the understanding perspective, Massey et

al. (2006) confirm that the life-cycle

phenomenon has been found meaningful by

SME managers.

Concerning growth itself, SME growth stage

models can provide value:

• To identify critical organisational transitions, as

well as pitfalls the organisation should seek to

avoid as it grows in size and complexity (Hanks

et al., 1993).

• To provide a better understanding of the growth

process of small firm development as input for

research and policy-making (McMahon, 1998).

• To assist with managerial growth problems and

internal processes, such as growth state

transitions, managerial consequences and

solutions (Davidsson et al., 2005).

• To assist with the management of key transition

points (Phelps et al., 2007).

• To assist in periods of change after operating for

some period of time in a definable state that then

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

508

changes, sometimes incrementally and other times

dramatically (Levie and Lichtenstein, 2010).

Although a wide variety of SME growth stage

models were published over the years, these SME

growth stage models, as indicated in the

introduction, did not escape criticism. It is important

to address such concerns, as SME growth stage

models are important for SME managers in order to

understand, manage and predict problems that are

likely to arise during SME growth.

This paper addresses one of these criticisms by

proposing an alternative solution to understand

typical transitions associated with SME growth.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

As part of our wider research project to position

BPM as management approach for SME growth,

design science research, following the process

suggested by Vaishnavi and Kuechler (2013), was

used to guide our research process. For the part of

the wider research presented in this paper, a

literature review of growth stage models was

conducted as first step. Based on the literature

review and the analysis of SME growth stages, it

became clear that a number of challenges exist with

SME growth stage models. One of the problems,

namely that stage models and life-cycle theories do

not accurately represent the growth of SMEs, was

identified as the focus of the problem to be

addressed in this paper. In addition, an analysis of

the corporate records of an actual SME was used to

confirm the criticisms of SME growth stage models

associated with the stages specifically. As outcome

of the two studies, a suggestion was made to

investigate whether a state transition model

approach could be an alternative to address this

problem. The development of the proposed model

involved an analysis of a representative set of

growth stage models, to identify state transitions,

and to define an SME growth state transition

classification framework. Mapping the state

transitions to the classification framework resulted

in the 5S SME Growth State Transition Model. To

demonstrate whether the SME Growth State

Transition Model addressed the concern that SME

growth stage models did not accurately represent the

growth of SMEs, the use of the model was

demonstrated by again applying it to the actual

SME. Further evaluation was done as part of the

wider research to position BPM as management

approach for SME growth.

4 ELABORATION OF THE

IDENTIFIED PROBLEM

4.1 Criticism of SME Growth Stage

Models

In the introduction, we mentioned the criticisms of

over-determinism, questionable empirical support

for growth stage models, and the fact that the stage

models tend to assume that all SMEs pass

inexorably through each phase of a growth stage

model. In addition, the following is a summary of

the criticisms identified based on the content of

reviews of SME growth stage models by Hanks et

al. (1993), McMahon (1998), Davidsson et al.

(2005), Massey et al. (2006), Phelps et al. (2007)

and Levie and Lichtenstein (2010):

• SME growth stage models are conceptually

rather than empirically based: There is a lack of

empirical validation of the proposed SME

growth stage models and even if empirical

studies were carried out, the outcome did not

favour the SME growth stage model theory

(Levie and Lichtenstein, 2010, Churchill and

Lewis, 1983).

• The definition of a stage is vague and too

general and the terminology is not explicitly

defined: Not only does the vague definition of a

stage make it difficult for the SME manager to

apply the model, but it also results in disparities

between models.

• The number of stages varies from between two

and eleven and the transition through the stages

result in variations: There is no consensus on

how many stages there are in SME growth stage

models, and whether organisations evolve

through the same series of stages.

• Descriptive model versus explanatory or

predictive model: The models serve well for

descriptive purposes, but have limited

explanatory or predictive power.

• Stage models and life-cycle theories do not

accurately represent the growth of SMEs:

Whether a specific SME growth stage model

originated from evolution or revolution as its

foundation (Greiner, 1972), stages of corporate

development (Scott and Bruce, 1987),

morphogenesis (Kazanjian, 1988) or an

organisational life cycle (Lippitt and Schmidt,

1967), the SME growth stage models are all

based on the underpinning assumptions of an

organismic metaphor regarding growth. Such

assumptions typically include the assumptions

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

509

that growth is linear, sequential, deterministic

and invariant. Levie and Lichtenstein (2010)

reviewed more than 100 SME growth stage

models published over a period of more than 40

years and concluded that stage models and life-

cycle theories do not accurately represent the

growth of SMEs.

Although all these criticisms are important, this

paper specifically addresses the last one related to

the stages of growth stage models.

4.2 Analysis of an Actual SME

An analysis of the corporate records of an actual

SME, company SME X, growing from a small

enterprise into a medium enterprise was used to

confirm the criticisms of SME growth stage models

associated with the stages specifically. The nature of

the underlying business of the small enterprise was

that of a consulting practice with a narrowly defined

service range. During the 2011/2012 financial year,

the number of full time employees was around 35

and the number of subcontractors varied between 10

and 20. The SME’s management wanted to

understand the areas of concern and wished to

identify the initiatives to be included in the business

plan to deliberately manage the growth from a small

to a medium enterprise.

During 2010, SME X developed an operating

model with one of the objectives being the growth of

the enterprise from a small into a medium enterprise.

The growth model for 2011/2012 financial year was

based on the replication of new pipelines. The

replication model (Ross et al., 2006) was therefore a

good fit to describe the growth model.

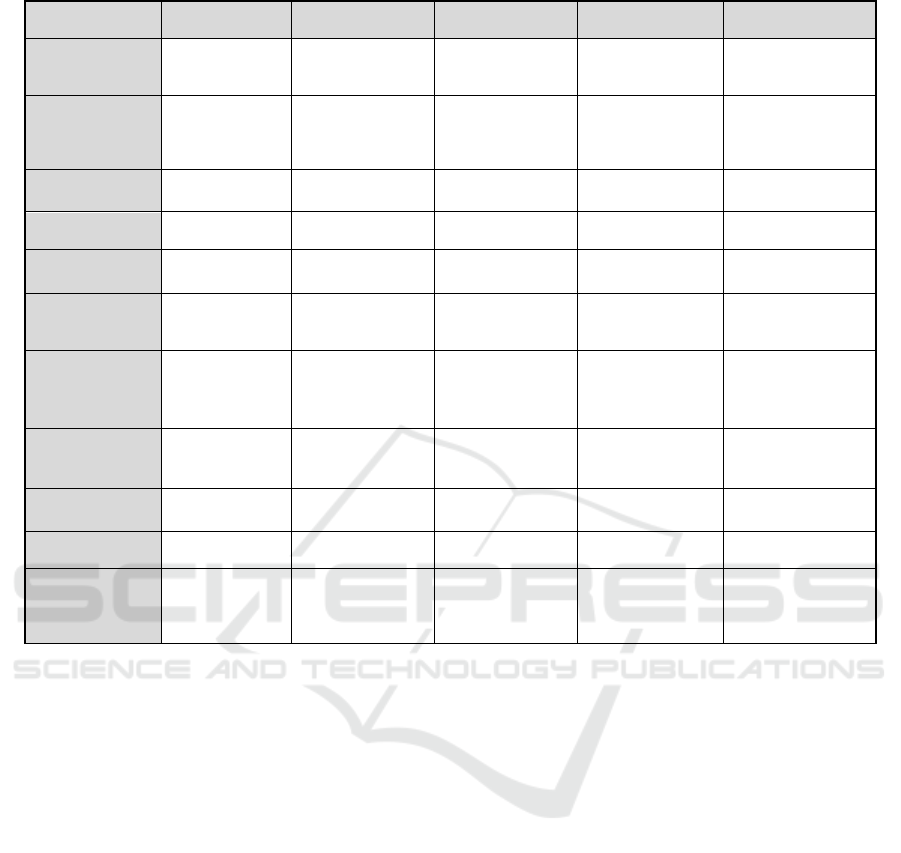

The Model for Small Business Growth (Scott

and Bruce, 1987) was used in the analysis of

company SME X. The Model consists of five stages

as illustrated in Table 1. The principles of the

Evolution of Five Phases of Growth (Greiner, 1972)

were the foundation of the Model for Small Business

Growth (Scott and Bruce, 1987). The Evolution of

Five Phases of Growth highlighted typical crises and

solutions as part of the transformation through the

different stages of SME growth. In the Model for

Small Business Growth, the different criteria, such

as the stage of the industry and key issues, were

presented in relation to each stage, from the

Inception stage (Stage 1) through to the Maturity

stage (Stage 5). For example, in Stage 1, Inception,

the key issues were those of obtaining customers and

economic production, which changed in Stage 5,

Maturity, to those of expense control, productivity,

and niche marketing if the industry was declining.

Using the 2010 operating model of company

SME X, the current and future states of the SME

were mapped according to the Model for Small

Business Growth (Scott and Bruce, 1987). The

outcome of this mapping of SME X is illustrated in

Figure 1

. Based on the SME growth stage model

principles, the expectation was that there would be a

single value for all areas of concern, e.g. for all areas

of concern the stage would be Stage 3, an indication

that the company was in that specific stage of

growth. A second expectation was that for all areas

of concern the future state would be the next stage,

for example Stage 4, indicating that the company

was moving to the expansion stage.

Figure 1: Current and Future States of Company SME X

based on 2010 information.

This mapping of the current and future states of

the company illustrated the challenges faced by the

company in determining its current and future stage

according to the guidelines of growth stage models.

For the product and market research as well as major

investments, the current state of company SME X

was still Stage 2, but for management style, systems

and controls and cash generation, the current states

were associated with Stage 4. For the other six areas

of concern, the current state of company SME X was

indicated as Stage 3. Regarding moving to the future

state the intent, for the majority of the areas of

concern, was to move to the next stage. However,

for three of the areas of concern, namely

management style, systems and controls as well as

major source of finance, there was no business value

in moving to the next stage.

Whether the observation, that an enterprise is not

necessarily in the same stage for all areas of

concern, was contributing towards, or was a result

of, the criticism of SME growth stage models, was

not clear.

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

510

Table 1: Model for Small Business Growth (Scott and Bruce, 1987).

Stage 1

Inception

Stage 2

Survival

Stage 3

Growth

Stage 4

Expansion

Stage 5

Maturity

Stage of Industry Emerging,

fragmented

Emerging,

fragmented

Growth, some larger

competitors, new

entries

Growth, shakeout Growth/ shakeout or

mature/ declining

Key Issues Obtaining

customers,

economic

production

Revenues and

expenses

Managed growth,

ensuring resources

Financial growth,

maintaining control

Expense control,

productivity, niche

marketing if industry

declining

Top Management

Role

Direct supervision Supervised

supervision

Delegation,

coordination

Decentralisation Decentralisation

Management Style Entrepreneurial,

individualistic

Entrepreneurial,

administrative

Entrepreneurial,

coordinated

Professional,

administrative

Watchdog

Organisation

Structure

Unstructured Simple Functional,

centralised

Functional,

decentralised

Decentralised

functional/product

Product and Market

Research

None Little Some new product

development

New product,

innovation, market

research

Production innovation

Systems and

Controls

Simple

bookkeeping,

eyeball control

Simple bookkeeping,

personal control

Accounting systems,

simple control

reports

Budgeting systems,

monthly sales and

production reports,

delegated control

Formal control,

systems management

by objectives

Major Source of

Finance

Owners, friends

and relatives,

suppliers leasing

Owners, suppliers,

banks

Banks, new partners,

retained earnings

Retained earnings,

new partners, secured

long-term debt

Retained earnings,

long-term debt

Cash Generation Negative Negative / breakeven Positive but

reinvested

Positive with small

dividend

Cash generator, higher

dividend

Major Investments Plant and

equipment

Working capital Working capital,

extended plant

New operating units Maintenance of plant

and market position

Product and Market Single line and

limited channels

and market

Single line and

market but

increasing scale and

channels

Broadened but

limited line, single

market, multiple

channels

Extended range,

increased markets

and channels

Contained lines.

Multiple markets and

channels

What was, however, confirmed with this analysis

of company SME X, is that the typical SME growth

stage model may be value adding to create

awareness of concepts related to growth. It also,

however, revealed that a new approach is required in

order to understand typical transitions during SME

growth, which can affect how to position BPM as

management approach for SMEs.

5 PROPOSED 5S SME GROWTH

STATE TRANSITION MODEL

The development of the proposed 5S SME Growth

State Transition Model involved five steps, starting

with the identification of a list of SME growth stage

models to consider, followed by the selection of a

list of ten representative SME growth stage models

to analyse in order to derive possible SME growth

state transitions. The terminology used in the ten

SME growth stage models was used to define an

SME growth state transition classification

framework. The detailed SME growth state

transitions were mapped against the SME growth

state transition classification framework, resulting in

the consolidated 5S SME Growth State Transition

Model.

The identification of an inventory of existing

SME growth stage models is discussed in section

5.1. The selection of a representative set of SME

growth stage models is described in section 5.2. The

set of SME growth state transitions derived from

these selected SME growth stage models is

described in section 5.3. In order to consolidate the

derived SME growth state transitions in section 5.5,

a classification framework is defined in section 5.4.

5.1 Identification of SME Growth

Stage Models

The literature review of SME growth stage models

by Levie and Lichtenstein (2010) included

references to 104 distinct articles referencing SME

growth stage models published during the period

1962 to 2006. Ten SME growth stage models,

representing the majority of concepts found in the

104 growth stage models, were identified for

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

511

inclusion in the detailed state transition analysis. An

in-depth analysis of all 104 models is identified as

further research.

The identification of articles describing SME

growth stage models, as candidates for selection of

one of the ten representative models, focused on two

periods, namely articles published in the period 1962

to 2006 and articles published during the period after

2006. For the period 1962 to 2006, candidates were

identified by cross-mapping the references of the

following literature reviews:

• Hanks et al. (1993) include references to eleven

articles describing SME growth stage models.

• McMahon (1998) refers to 31 articles describing

SME growth stage models.

• Davidsson et al. (2005) refer to nine articles

describing SME growth stage models.

• Phelps et al. (2007) include 33 different

references in their SME life cycle literature

review.

• Levie and Lichtenstein (2010) cite 104 articles

describing SME growth stage models. For the

purpose of the identification of ten

acknowledged references to SME growth stage

models, only references also listed by one of the

other literature reviews or references that were

cited four or more times were considered,

resulting in 28 of the 104 articles being included

in the candidate list of SME growth stage model

references.

For the period after 2006, a review of literature

resulted in the identification of an additional seven

references to SME growth stage models.

5.2 Selection of Representative SME

Growth Stage Models

The selection of the ten representative SME growth

stage models from the identified publications of

SME growth stage models was done by applying the

following criteria:

• A reference to an SME growth stage model was

included if the reference was referenced by at

least four of the five literature reviews.

• As an additional test it was checked that the

references most cited, according to Levie and

Lichtenstein (2010), were all included for

consideration as a representative SME growth

stage model.

• The SME growth stage models were further

examined to determine if the description of an

SME growth stage model in literature was

sufficient to derive SME growth state

transitions.

The seven references published after 2006 were

also considered as candidate sources. Only three of

these seven references included enough detail to

derive transitions. The SME growth stage models

described by Phelps et al. (2007), Lester and Parnell

(2008) and Levie and Lichtenstein (2010) were

consequently included in the final list of references

of SME growth stage models.

The final selection of ten representative

references used as sources to derive SME growth

state transitions from SME growth stage models is

listed in Table 2. The name used to identify a

specific SME growth stage model was derived from

the content of the published article.

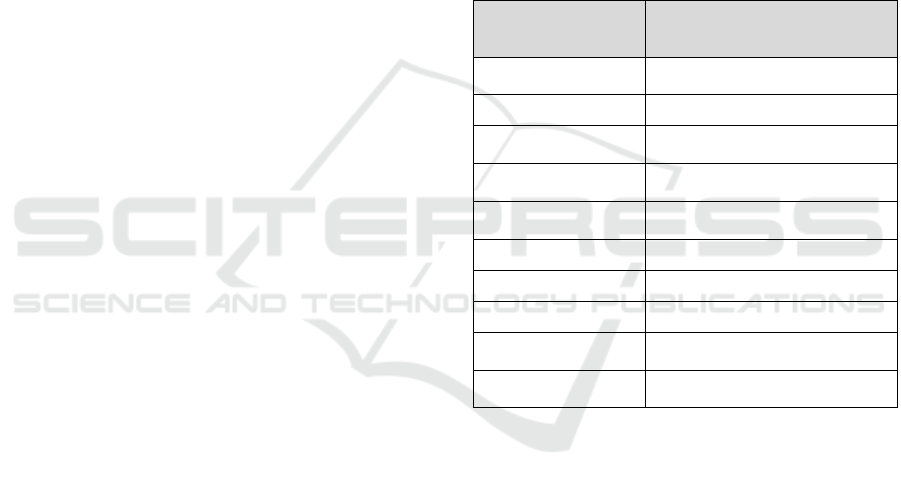

Table 2: Representative References to SME growth stage

models.

Representative List of

References to SME

Growth Stage Models

Name of the SME Growth Stage

Model

Greiner (1972) Evolution in Five Phases of Growth

Model

Adizes (1979) Organisational Passages Model

Churchill and Lewis

(1983)

Stages of Small Business Growth

Model

Quinn and Cameron

(1983)

Integrated Life Cycle Model

Miller and Friesen

(1984)

Corporate Life Cycle Model

Scott and Bruce (1987) Model for Small Business Growth

Hanks et al. (1993) Structural Variable Model

Phelps et al. (2007) Tipping Point Framework

Lester and Parnell

(2008)

Organisational Life Cycle Scale

Levie and Lichtenstein

(2010)

Stage Categories Model

5.3 Deriving SME Growth State

Transitions

Each of the SME growth stage models, listed in

Table 2, was analysed and the SME growth state

transitions were derived for use in the development

of the 5S SME Growth State Transition Model. The

focus of this activity was to determine whether it

was possible to derive the states as the result of a

transition from the SME growth stage models.

As example, the result of deriving the growth

state transitions from the study by Hanks et al.

(1993) is included in this paper. In the Structural

Variable Model (Hanks et al., 1993), it is proposed

that each life cycle stage of an enterprise consists of

an unique configuration of variables related to the

organisation context and structure. Two sets of

variables are used to measure the context and the

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

512

structure of the enterprise. The contextual variables

include measures such as age, size and rate of

growth, and were not used to derive states related to

SME growth. The structural variables, which were

used to derive states related to SME growth, include

measures of vertical differentiation, structural form,

formalisation, decision-making, specialisation and

centralisation. The states derived from the Structural

Variable Model are listed in Table 3.

A similar process was followed to identify

growth state transitions from the other nine

representative SME growth stage models.

5.4 Proposed 5S Classification

Framework for SME Growth State

Transitions

The first step towards the definition of the 5S

Classification Framework was the consolidation of

all the states from the analysis of the ten selected

SME growth stage models.

The ten selected SME growth stage models did

not use the same classification scheme to group the

different states. A prerequisite for the consolidation

of the states was therefore the development of a

classification framework to group the different

states, resulting in the 5S SME Growth State

Classification Framework. Based on the principle

that seven plus/minus two elements are easier to

process and to remember, the objective was to group

the identified states into a framework with a

maximum of nine elements.

The resulting 5S SME Growth State

Classification Framework, as presented in Table 4,

includes five classes as well as sub-classes. The

names of derived classes each starts with the letter S,

namely Strategy, Structure, Systems, Style of

Management and Staff. As a way of verifying the

classification, it was compared with other SME

growth stage models. The classes of the 5S SME

Growth State Classification Framework was similar

to the categories of attributes as described by Levie

and Lichtenstein (2010).

5.5 Consolidation into 5S SME Growth

State Transition Model

The consolidated list of states derived from the

representative set of growth stage models was

thereafter mapped to the 5S SME Growth State

Classification Framework, as presented in Table 5 to

Table 12 (see Appendix). The content of these tables

was determined through synthesis.

Table 3: States derived from Structural Variable Model

(Hanks et al., 1993).

Context

State Description

Formalisation

Formal policies and procedures guide most decisions.

Important communication between departments is

documented by memo.

Formal job descriptions are maintained for each

position.

The top management team is comprised of specialists

from each functional area.

Reporting relationships are formally defined.

Lines of authority are specified in a formal organisation

chart.

Rewards and incentives are administered by objective

and systematic criteria.

Capital expenditures are planned well in advance.

Plans tend to be formal and written.

Formal operating budgets guide day-to-day decisions.

Organisation

(Structure)

Simple (Owner/Manager assisted by individuals with

varying responsibilities. No divisions or functional

departments)

Function (Separate departments or functions (i.e.

engineering, marketing, production, personnel)

Division (Separate groups for similar products, markets

or geographic regions)

Top

management

dec

i

s

i

o

n

Entrepreneurial (One individual makes decisions based

on personal judgment)

Professional (Functional specialists make decisions

based on expertise and analytical tools)

Centralisation

Who is the last person whose permission must be

obtained before legitimate actions may be taken in the

following areas?

Promotion of a direct worker

Addition of a new product /service

Unbudgeted expenditure ($500-$1000 in 1994)

Selection of type or brand of new equipment

Dismissal or firing of a direct worker

Specialisation (Responsible person per area)

Public/shareholder relations

Shipping and receiving

Building maintenance

Customer/Product service

Production planning / scheduling

Personnel

Advertising

Legal affairs

Purchasing

Sales

Quality control

Employee training

Market research

Accounting

Inventory control

Industrial engineering

Research and development

Safety / security

Payroll

Finance

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

513

Table 4: 5S Growth State Classification Framework.

Class Sub-Classes

Strategy

• Product leadership

• Operational excellence

• Market share

• Customer focus

Structure

Systems

• Process

• Information systems

• Controls

• Planning

Style of

Management

• Delegation of authority

• Decision-making style

Staff

The consolidation was based on the classes and sub-

classes as defined by the 5S State Growth

Classification Framework. This final deliverable is

referred to as the 5S SME Growth State Transition

Model and is collectively represented by the content

of Table 5 to Table 12.

The 5S SME Growth State Transition Model is

structured in such a way that it can be used as an

assessment sheet, by adding three columns (current

state, future state and not applicable), allowing the

SME manager to indicate the current state as well as

the future state, or whether the statement is not

applicable to the specific SME. The future state

column would indicate the list of transitions to be

managed for the specific SME. If the current state is

also the future state, both cells should be selected.

5.5.1 SME Assessment of the Strategy as

Differentiator in the Market

The consolidation of the states associated with the

Strategy (S1) class is grouped in Table 5 (see

Appendix) according to the following four

strategies: product leadership, operational

excellence, marketing or distribution channels and

customer focus.

5.5.2 SME Assessment of Structure

SME growth results in a transition from an informal

structure to a more formal Structure (S2), with a

number of options, as presented in Table 6 (see

Appendix).

5.5.3 SME Assessment of the SME as a

System

Within the context of an SME as a system, a

‘system’ is referring to a set of distinct parts that

interact to form a complex whole. The four distinct

parts of the Systems (S3) class are the processes,

enabling information systems, controls and

specifically the concept of planning as part of the

SME as a system. These sub-classes of states are

included in Table 7 to Table 10 (see Appendix).

5.5.4 SME Assessment of the Style of

Management

The style of management matures as the SME

growths. Within the 5S SME Growth State

Transition Framework the Style of Management (S4)

has two concepts related to the SME assessment,

namely the delegation of authority and the decision

making style. The sets of state statements are

included in Table 11 (see Appendix).

5.5.5 SME Assessment of the Staff

Component

The state descriptions that form part of the Staff (S5)

component is included in Table 12 (see Appendix).

6 DEMONSTRATION OF THE

APPLICABILITY OF THE 5S

SME GROWTH STATE

TRANSITION MODEL

The applicability of the proposed 5S SME Growth

State Transition Model was illustrated by again

studying company SME X to demonstrate that the

identified growth state transitions are indeed

applicable to SMEs.

The study was based on the historical records of

company SME X. The states were mapped to four

major periods in the growth of the company. The

growth was defined by the number of staff and

contractors in that specific period. These periods can

be summarised as:

• 2002 - 2005: This period was associated with

early establishment, initially with four founders,

and ending with seven permanent staff members

and five contractors.

• 2006 - 2009: This period was related to

partnering with a Broad-Based Black Economic

Empowerment partner as well as a product

vendor. The staff numbers grew to fifteen

permanent staff members, and the number of

contractors varied between five and ten.

• 2010 - 2013: This was a period of growth with a

well-defined business model, restructuring of

the shareholders model, and a maximum of just

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

514

over fifty staff members and close to twenty

contractors.

• 2014: This year was a period of transformation

and diversification in order to adapt to market

conditions. The number of staff members

declined and the use of contractors was

minimal. The period associated with a specific

growth state transition statement is indicated in

Table 5 to Table 12 (see Appendix).

The demonstration of the 5S SME Growth State

Transition Model as applied to the history of

company SME X highlighted the following:

• The Model would mature by use with the

addition, deletion and consolidation of growth

state transitions.

• Some of the growth state transitions may be

industry-specific.

• Application of the Model could result in various

outcomes, such as not being applicable, single

occurrence, multiple occurrences and repetitive

occurrences.

The most important awareness was that the

Model successfully eliminated the constraint of

stages associated with SME growth stage models.

7 CONCLUSION

The research objective of the work presented in this

paper was to develop an SME growth state transition

model that can be used as input to our research to

position BPM a management approach for SMEs.

The requirement was for such a model to address the

criticism regarding the sequential nature of the

existing SME growth stage models. The

development of the 5S Growth State Transition

Model included: (1) the identification of SME

growth state transitions as defined in existing SME

growth stage models, (2) the definition of a 5S SME

Growth State Classification Framework for the

classification of the growth state transitions, and (3)

the consolidation of the identified growth state

transitions by mapping them to the 5S SME Growth

State Classification Framework.

A study based on information from company

SME X demonstrated that the 5S Growth State

Transition Model is a fair representation of the SME

growth state transitions. These state transitions

identified potential changes and transformations in

the organisation.

BPM is typically a discipline that adds value

during changes and/or transformations. The value

contribution of the 5S SME Growth State Transition

Model can be summarised as a better understanding

of the transitions associated with SME growth,

making it possible to position BPM as a

management approach to manage change during

transformation. The next challenge is to develop a

BPM approach, supportive of self-sufficiency, which

can be used as input to the development of a BPM

approach to assist SME managers to manage a

specific growth state transition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work presented in this paper was conceptualised

based on the research for the PhD Degree of Dina

Jacobs, completed in 2016, at the Vaal Triangle

Campus of North-West University, South Africa.

Paula Kotzé and Alta van der Merwe were her PhD

promotors.

REFERENCES

Adizes, I. (1979). Organizational Passages--Diagnosing

and Treating Lifecycle Problems of Organizations.

Organizational Dynamics, 8, 3-25.

Churchill, N. C. & Lewis, V. (1983). The five stages of

small business growth. Harvard Business Review, 61,

30-50.

Davidsson, P., Achtenhagen, L. & Naldi, L. (2005).

Research on Small Firm Growth: A Review.

DTI. (1995). National Strategy for the Development and

Promotion of Small Business in South Africa. In:

Insutry, D. O. T. A. (ed.).

DTI. (2008). Annual Review of Small Business in South

Africa 2005-2007.

Greiner, L. E. (1972). Evolution and revolution as

organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 50, 37-

46.

Hanks, S. H., Watson, C. J., Jansen, E. & Chandler, G. N.

(1993). Tightening the life-cycle construct: a

taxonomic study of growth stage configurations in

high-technology organizations. Entrepreneurship

Theory and Practice, 18, 5-29.

Jacobs, D., Kotzé, P., van der Merwe, A. & Gerber, A.

(2011). Enterprise Architecture for Small and Medium

Enterprise Growth. In: Albani, A., Dietz, L. & Verelst,

J. (eds.) Advances in Enterprise Engineering V - First

Enterprise Engineering Working Conference (EEWC

2011). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Jones, N. (2009). SMEs Life Cycle -- Steps to Failure or

Success? AU-GSB e-Journal, 2, 3-14.

Kazanjian, R. K. (1988). Relation of dominat problems to

stages gowth in technology-based new ventures.

Academy of Management Journal, 31, 257-279.

Lester, D. L. & Parnell, J. A. (2008). Firm size and

environmental scanning pursuits across organizational

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

515

cycle stages. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development, 15, 540-544.

Levie, J. & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2010). A Terminal

Assessment of Stages Theory: Introducing a Dynamic

States Approach to Entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34, 317-350.

Lippitt, G. L. & Schmidt, W. H. (1967). Crises in a

developing organization. Harvard Business Review,

47, 102-112

Massey, C., Lewis, K., Warriner, V., Harris, C., Tweed,

D., Cheyene, J. & Cameron, A. (2006). Exploring firm

development in the context of New Zealand SMEs.

Small Enterprise Research: The Journal of SEAANZ,,

14, 1-13.

McMahon, R. (1998). Stage Models of SME Growth

Reconsidered.

Miers, D. 2011). Scope of BPM Initiatives.].

Miller, D. (1987). The Genesis of Configuration.

Academy of Management Review, 12, 686-701.

Miller, D. & Friesen, P. H. (1984). A Longitudinal Study

of the Corporate Life Cycle. Management Science, 30,

1161-1183.

Penrose, E. (1959). The Theory Oxford, Oxford

University Press.

Perenyi, A., Selvarajah, C. & Muthaly, S. (2008). The

Stage Model of Firm Development: A

Conceptualization of SME Growth. Proceedings of

Regional Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research

2008: 5th International Australian Graduate School of

Entrepreneurship (AGSE) Entrepreneurship Research

Exchange. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Australian

Graduate School of Entrepreneurship, Swinburne

University of Technology.

Phelps, R., Adams, R. & Bessant, J. (2007). Life cycles of

growing organizations: A review with implications for

knowledge and learning. International Journal of

Management Reviews, 9, 1-30.

Quinn, R. E. & Cameron, K. (1983). Organizational life

cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some

preliminary evidence. Management Science, 29, 33.

Ross, J., Weill, P. & Robertson, D. (2006). Enterprise

Architecture as Strategy Creating a Foundation for

Business Execution, Boston, Harvard Business School

Publishing.

Scott, M. & Bruce, R. (1987). Five stages of growth in

small business. Long Range Planning, 20, 45-52.

Vaishnavi, V. & Kuechler, W. (2013). Design Research in

Information Systems. Available:

http:desrist.org/design-research-in-information-

systems [Accessed 18 July 2015 2015].

Zheltoukhova, K. & Suckley, L. (2014). Hands-on or

hands-off: effective leadership and management in

SME's. Chartered Institute of Personnel and

Development in collaboration with Sheffield Hallum

University.

APPENDIX

The transition period(s) for company SME X is

indicated in square brackets and colour blue after the

transition statement. Refer to section 6 for a

description of the transition periods.

Table 5: SME Assessment of the Strategy as Differentiator in the Market.

SME Assessment of the Strategy as Differentiator in the Market (S1)

S1.1 Product leadership as differentiator in the market The SME is offering a unique or superior product to the market. It is important for

the SME to gain and/or maintain the product leadership in the market.

S1.1.1 Diversification by acquisition is a strategy to gain and/or maintain product leadership in the market. [2006-2009]

S1.1.2 Major and frequent product/service innovations is a strategy to gain and/or maintain product leadership in the market through new

products. [2014]

S1.1.3 Small and incremental product/service modifications is a strategy to gain and/or maintain product leadership in the market. [2006-

2009; 2010-2013; 2014]

S1.2 Operational excellence as differentiator in the market

The SME is differentiated by operational excellence in the market. The differentiator may be based on price, reliability, flexibility and/or

responsiveness. The reliability is referring to quality and/or on time delivery. It is important for the SME to gain and/or maintain the

competitive advantage in the market based on operational excellence.

S1.2.1 Managing the supply-chain upstream and/or downstream is a strategy to gain and/or maintain a competitive advantage in the market.

Working closely with suppliers and the distribution network enables an integrated end-to-end service as part of operational excellence. [Not

applicable]

S1.2.2 Identification of a niche product/service to close a gap in the end-to-end supply-chain delivered is a strategy to gain and/or maintain a

competitive advantage in the market. [2014]

S1.2.3 Economic production is a strategy to gain/or maintain a competitive advantage in the market. The focus is on efficiency, improving

the production/service delivery process, to eliminate rework and to cut cost. [2014]

S1.3 Marketing / distribution channels as differentiator in the market

The strategy is to establish the brand in the market and/or to create a network of distribution channels for the SME to gain and/or maintain

market share.

S1.3.1 Expansion of market and distribution channels is a strategy to ensure dominance of distribution channels and the associated

competitive advantage in the market. [2014]

S1.3.2 Geographical expansion is a strategy towards diversification and getting entry to new markets. [2006-2009]

S1.3.3 Market segmentation with different lines of products/services per market is a strategy for the SME to gain and/or maintain a

competitive advantage in the market. [2006-2009; 2010-2013; 2014]

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

516

Table 5: SME Assessment of the Strategy as Differentiator in the Market. (Cont.)

S1.4 Customer focus as differentiator in the market

The SME creates and maintains strong customer relationships and the strategy is to ensure that the SME is the preferred product or service

provider of the customer.

S1.4.1 Customer preference requires diversification of marketing, products and administrative practices, Scanning customer preference and

acting on it is a strategy to gain and maintain the competitive advantage in the market. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S1.4.2 High performance enterprises have a stronger awareness of customers and customer needs and it is a strategy of the SME to know

and obtain customers to become/remain a high performance enterprise. [2014]

Table 6: SME Assessment of Structure.

SME Assessment of the Structure (S2)

It is possible to select more than one option for example decentralised geographically (S2.4) as well as shared services (S2.6).

S2.1 Simple informal structure

The owner or manager is assisted by individuals with varying responsibilities. There are no divisions or functional departments.

An informal structure is built around the owner manager and it is typical of small companies in the early stages of their development.

The entrepreneur often has specialist knowledge of the product or service. [2002-2005]

S2.2 Functional structure

There are separate departments or functions (i.e. engineering, marketing, production, personnel). It is most appropriate to small

companies which have few products and locations and which exist in a relatively stable environment.

• Product based departments: Structuring by product involves organising the business into departments, each of which focuses on

a different product.

• Customer based departments: A business may be divided by the type of customer (e.g. public sector or private sector customers).

[Not applicable]

S2.3 Decentralised by geographical area

Some businesses organise their activity according to geographical area. This is common in large multinational companies but it might

also be appropriate for medium-sized businesses, for example a group of taxi firms, a small retail chain or a fast-food chain with several

branches. Organising by area means each site can operate according to local demand

b

ut still be directed by business policy. Sometimes

logistics relating to shipping, resources and staff make geographical structure the best choice. [2006-2009]

S2.4 Divisional structure

There are separate groups for similar products, markets or geographic regions. There is a degree of difference among organisational

divisions in terms of their overall goals, marketing and production methods and decision-making styles. Managers who are responsible

for their own resources head them. Divisions are likely to be seen as profit centres and may be seen as strategic business units for

planning and control purposes. [2014]

S2.5 Shared services structure

Shared services is the provision of a service by one part of an organisation or group where that service had previously been found in

more than one part of the organisation or group. Thus the funding and resourcing of the service is shared and the providing

department/division effectively becomes an internal service provider. [2006-2009]

Table 7: SME Assessment of the Processes as part of the SME as System.

SME Assessment of the Processes as part of the SME as System (S3.1)

S3.1 Processes

A business process describes the work that is being done in a business. As the SME grows it is important to define, standardise, align and

optimise the processes overtime. In order to identify opportunities for optimisation the initial step is to measure the performance of the

processes.

S3.1.1 The record keeping processes to keep record of all transactions as well as all communications are defined and implemented.

[Since 2002-2005 part of operations]

S3.1.2 The way of work to eliminate inefficiencies and to improve productivity is reviewed. Redundant activities are identified and

removed. The level of standardisation of the process is monitored with the objective to reduce rework over time. Note: Efficiency is

referring to how work is being done. [2006-2009; 2010-2013;2014]

S3.1.3 The way of work is reviewed to ensure all processes are effective, i.e. that what is being done and the outcome of a process is

adding value. Note: Ensure that you do not increase the efficiency of a process that is not effective. [2010-2013; 2014]

S3.1.4 Processes to consider for specialisation are identified. At the early stages of the SME the owner(s) is filling all the roles. As the

SME grows specialised processes are allocated to specialists or outsourced to a third party. The following are examples of processes to

be considered for specialisation: public/shareholders relations, shipping and receiving, building maintenance, customer/product service,

production planning/scheduling, personnel, advertising, legal affairs, purchasing, sales, quality control, employee training, market

research, accounting, inventory control, industrial engineering, research and development, safety/security, payroll, finance. [Since 2006-

2009 part of operations]

S3.1.5 The performance of a business process is monitored, starting with the selection of a key performance indicator (KPI) and

measurement of this one KPI. An example is to measure on time delivery or another example is to monitor the number of rework

requests as a result of quality deviations. KPIs are often related to time, cost or quality. [2010-2013; 2014]

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

517

Table 8: SME Assessment of the Information Systems as part of the SME as System.

SME Assessment of the Information Systems as part of the SME as System (S3.2)

S3.2 Information Systems

Information systems are referring to technology that is enabling the business process. Examples are spreadsheets, cloud based

information systems or even mobile applications.

S3.2.1 Reporting is enabled by an information system to track revenue and expenses on a monthly basis. [Since 2002-2005 part of

operations]

S3.2.2 A financial system is implemented to automate the financial transactions including invoicing and management of expenses

together with the management of creditors and debtors. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S3.2.3 A marketing system is implemented to manage customer information and lead management. [2014]

S3.2.4 A production system or professional services system is implemented with a time sheet system playing an important role in

professional services and the management of raw material and batches in production. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S3.2.5 A human resource management system is implemented to manage human resources, payroll and compliance with labour

legislation. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S3.2.6 A logistics or distribution system is implemented to manage delivery of products. [Not applicable]

S3.2.7 A management information system is implemented for information dissemination and retrieval. Relevant and undistorted

information reach decision makers on time. [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S3.2.8 Coordination of diverse activities is enabled through inter alia collaboration systems, document management or enterprise content

management and workflow. [2014]

S3.2.9 Information systems is used to better serve markets. Examples are online trading, tracking of orders, social media for marketing

and process execution (using workflow, business rule engine and an integration platform). [2014]

Table 9: SME Assessment of Controls as part of the SME as System.

SME Assessment of the Controls as part of the SME as System (S3.3)

S3.3 Controls

Controls are defined and implemented in order to limit or rule actions or behaviour. Controls are embedded in the processes and to

implement controls it is important to measure compliance to these controls.

S3.3.1 Rules (policies, procedures and standards) are formalised and institutionalised.. SME growth is often associated with an increase in

staff, and it is important to set the rules and apply the rules consistently to all staff. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S3.3.2 Operational controls such as the control of stock are implemented. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S3.3.3 Financial controls including the performance of sub-units, departments, divisions and products are monitored.[Since 2010-2013

part of operations]

S3.3.4 The compliance to regulations and quality standards is monitored. [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S3.3.5 The SME is always ready for a due diligence appraisal whether it is to support a business plan to attract funding, whether it is

undertaken by a prospective shareholder or whether it is part of the evaluation of the SME as a supplier on a large contract. A due

diligence appraisal establishes the assets and liabilities of a company and evaluate its commercial potential. Well-established policies,

procedures and rules as well as operational and financial controls contribute towards a positive outcome of a due diligence appraisal.

[2010-2013]

Table 10: SME Assessment of Planning as part of the SME as System.

SME Assessment of Planning as part of the SME as System (S3.4)

S3.4 Planning

Planning is the process of predicting how the future should look like to achieve effectiveness and efficiency in a company. Planning

follows a specific process. In order to manage the performance of a business it is important to monitor the progress against a plan such as

the financial budget.

S3.4.1 Cash is managed to make provision for the investments required to enable growth. Cash forecasting is based on the financial plan

(the budget) as well as the actual financial results. [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S3.4.2 The processes for planning, scheduling and coordination are defined and implemented. The allocation of resources to complete

specific work is known as scheduling. Coordination is the synchronisation and integration of activities, responsibilities, and command and

control structures to ensure efficient completion of work. [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S3.4.3 A long-term vision is in place to ensure that the tactical and operational plans are driven by the strategic vision. [2006-2009; 2010-

2013; 2014]

S3.4.4 Both operational and strategic plans are defined for marketing, production, human resources and finance. [Since 2010-2013 part of

operations]

S3.4.5 An operating budget to support strategies is in place and is used to manage operations. [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S3.4.6 Capital expenditure is planned well in advance. [2014]

S3.4.7 A marketing forecast is available. [2014]

AEM 2017 - 1st International Workshop on Advanced Enterprise Modelling

518

Table 11: SME Assessment of Style of Management.

SME Assessment of Style of Management

S4.1 Delegation of Authority

Delegation of authority in the context of SME growth means that the SME manager (often then owner) is entrusting someone else to do

parts of the job on the SME manager. The state transitions associated with the delegation of authority are grouped as level of delegation,

management of the delegation of authority and the authority associated with the delegation.

Note: Level of Delegation

S4.1.1 The SME manager is supervising the employees directly. [2002-2005]

S4.1.2 Supervisors are responsible for the supervision of employees. According to Zheltoukhova and Suckley (2014) only 12% of

employees of small enterprises (10-49 employees) report to a manager with a span of control larger than ten. [2010-2013]

S4.1.3 A functional structure results in delegation of authority to functional managers. [Not applicable]

S4.1.4 A divisional structure results in delegation of authority to divisional managers. [2010-2013]

Note: Management of the Delegation of Authority

S4.1.5 Delegation of authority is managed by setting objectives for managers and measure performance against the objectives.[Since

2010-2013 part of operations]

S4.1.6 Delegation of authority is managed by putting a process in place to escalate exceptions to the SME manager. [Since 2010-2013 part

of operations]

Note: Authority associated with the Delegation

S4.1.7 Delegation of authority includes authority to promote direct workers, dismiss direct workers, add new products or services, select

new equipment and approve unbudgeted expenditure. [Not applicable]

S4.1.8 Delegation of day-to-day operating authority. [2010-2013]

S4.1.9 Centralisation of strategy-making power (acquisitions, diversification and vision). [Since 2010-2013 part of operations]

S4.1.10 Formal definition of reporting relationships. Lines of authority specified in organisation chart. [2002-2005]

S4.2 Decision making Style

Decision making style is providing insight on how a manager is making decisions.

S4.2.1 Intuitive decision making is replaced with an understanding of the decision making process to make more informed decision.

[2002-2005]

S4.2.2 Specialists are appointed to make decisions on the basis of expertise and analysis of information. [Since 2010-2013 part of

operations]

S4.2.3 Participation of employees in the decision making process is promoted with an associated increase in the level of motivation of

employees. [2014]

Table 12: SME Assessment of the States Associated with the Staff Component.

SME Assessment of the Staff Component (S5)

S5.1 An incentive scheme is included as part of the remuneration package. [2010-2013]

S5.2 A performance management process is defined and implemented. [2006-2009]

S5.3 Job descriptions are based on the processes and clear role clarification is ensured. [2006-2009]

S5.4 A training and development programme is implemented for employees. [Since 2006-2009 part of operations]

S5.5 Communication and change management are in place. [2006-2009]

S5.6 The culture and values of the SME are protected as the SME grows. [2014]

A Growth State Transition Model as Driver for Business Process Management in Small Medium Enterprises

519