Self-assessment of Higher Online Education Programmes

Renata Marciniak

Department of Applied Pedagogy, Autonomous University of Barcelona, UAB, Bellaterra-Cerdanyola del Vallés, Spain

Keywords: Higher Online Education, Online Education Programme, Quality, Self-assessment, Model.

Abstract: This paper presents a PhD project which purpose is to design a model to be applied in the self-assessment of

online education programmes. The starting point of the design is a bibliographical-documental analysis of

the elements of online education programmes as well as a specific bibliographical study of the standards,

models and tools created in order to evaluate the quality of online education. Based on the results of the said

analysis, a model for the self-assessment of higher online education programmes is created, composed of

two variables, fourteen dimensions and one hundred eleven indicators. Before creating the definitive model,

two drafts were created and subject to the validation by international online education experts and discussed

in two discussion groups: one composed of experts in online education and the other one composed of

online students. Nevertheless, in order to verify the total utility of the designed model it should be applied in

the self-assessment of various online programmes in different countries.

1 RESEARCH PROBLEM

In order to improve the quality of online

programmes, persons in charge of implementing the

said programmes require, apart from the point of

view offered by external assessments, their own

point of view regarding the condition of the

program, its strengths, weaknesses and improvement

opportunities. This approach is made possible

through self-assessment, which is the first step of the

ongoing improvement process carried out when:

“An academic unit, seeking to create quality control and

guarantee mechanisms, collects substantial information

regarding the achievement of its objectives and analyses

it, based on previously defined criteria and indicators in

order to make decisions that will guide its future actions,

selecting and proposing improving plans” (CNAP

, 2001,

p.10).

As a matter of fact, self-assessment provides

information regarding the modifications that should

be introduced in the learning program in order to

improve it. This means that self-assessment should

always precede any decision or action to be taken by

the university to improve its learning programmes.

Nevertheless, in order for self-assessment to be

an useful tool for the review of online programmes

and introduction of necessary modifications or

improvement actions, it should be conducted

according to a model that takes into consideration

the specific contexts of the online education, as

postulated by Veytia & Chao (2013): “Assessing the

traditional and online education requires different

parameters and models, that respond to the

pedagogical model, upon which they are based on,

as well as to its objectives and student admittance

and graduation profiles” (p. 12).

However, as shown by practice, the current trend

in self-assessing online education programmes,

especially when it comes to universities that offer

both traditional and virtual education programmes, is

to perceive them as a series of activities

complementary to traditional education programmes.

As a result, the quality of online programmes is

assessed in the same manner as traditional education

programmes, that is, by using the criteria and

indicators designed for assessing the quality of

traditional education without applying quality

dimensions specifically designed for virtual

education (Chmielewski, 2013).

At this point, it is worth noting that accreditation

organizations assess and certify online programmes

by applying the same models as the ones applied to

traditional education programmes, as shown by the

results of the research conducted by the Polish

National Centre for Supporting Vocational and

Continuing Education within the project “Diagnosis

of the current situation of distance learning in

Poland and other European countries” cofounded by

Marciniak R.

Self-assessment of Higher Online Education Programmes.

In Doctoral Consortium (CSEDU 2017), pages 3-10

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

the European Union. In the report of the said

research we can read, among others:

“All higher education programmes in European Union

receive their accreditation based on the same principles

and criteria. This refers both to online and traditional

education programmes. The same applies to countries

with specific proceedings for the accreditation of higher

education online programmes (Germany, Spain and

Norway). Even though, each country has its own system

for the accreditation and monitoring of the quality of

higher education, higher education online programmes

are assessed in the same manner as traditional education

programmes”. (Chmielewski, 2013, p. 49,)

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that we

can encounter several models developed to assess

virtual education, such as those mentioned by Hilera

(2010) or Motz (2013). Nevertheless, the said

models combine a variety of approaches and,

sometimes, respond to contradictory paradigms and,

thus, propose divergent dimensions and meanings

assigned to these dimensions to assess the quality of

virtual education. The indicators proposed by the

said models rarely underline the need to assess the

quality of the program itself, as well as of its

planning, application and impact (ongoing

assessment), as postulated by Martínez (2013), who

states that:

“Program evaluation is the systematic collection of

information regarding a program in order to meet specific

needs, that is focused on 1) the quality of the program

itself, its basic elements, structure and coherence; 2) the

planning of its putting into action, taking into

consideration human, material and organizational

resources, 3) the development of the program and 4) the

program results in the immediate, medium and long term

in order to verify and assess the degree and quality with

which the needs have been met and the problems have

been solved (Martínez, 2013, p. 197).

Another equally relevant issue is the scarce literature

regarding the self-assessment of higher online

education programmes. Neither Spanish, nor English

and Polish literature mention the aforementioned

self-assessment. We do not encounter results

regarding the said self-assessment in any of the

searched databases (ERIC, Francis, Eudised,

Eurybase and Teseo).

The lack of knowledge of the universities when it

comes to the correct self-assessment of higher online

education programmes, the lack of models that

contribute to the said self-assessment and the lack of

detailed bibliography in this area inspired us to

conduct our own research.

2 OUTLINE OF OBJECTIVES

The general objective of the thesis is to design and

validate a model to be applied by universities in the

assessment of online education programmes, which

includes assessment of the quality of the program

itself, as well as its continuous assessment. This way

the model is expected to become an useful tool in

order to evaluate and improve all the elements of

online education programmes, as well as the three

phases of its existence, that is, the initial phase, the

development phase and the final phase.

In the context of the general objective, the

following specific objective have been formulated:

- In the Area of Bibliography:

• To identify and describe, through

bibliographical and documentary revision, all

the elements of a higher education online

program that define its quality and can

constitute the dimensions of a self-assessment

model for the said program.

• To characterize the assessment of online

programmes.

• To identify and analyse different standards,

models and tools developed to assess the

quality of online education that can be used in

the self-assessment of higher online education

programmes.

- In the Area of Empirical Research:

• To design a model applicable to the self-

assessment of higher online education

programmes, that integrates the assessing of

the quality of the program itself, as well as the

ongoing assessment of the program.

• To validate the model by different audiences

and analytical proceedings.

• To verify the utility of the designed model by

applying it in the self-assessment of different

online programmes.

- In the Area of the Proposed Own Solution:

• To present the model of self-assessment of

higher online education programmes.

• To make different proposals in order to

facilitate the implementation of the model.

3 STATE OF THE ART

Currently, there are many models that can be used to

assess online programmes. These models can be

divided in two groups:

1) Traditional models created to assess traditional

education programmes and adapted to assess

online education programmes and

2) Models developed with the purpose of assessing

online education in general which are used as

reference to assess educational online

programmes.

As for the models of the first group, among the

traditional models recommended by many authors

(Bieliukas and Ornes, 2014; Díaz-Maroto, 2009;

Ruhne and Zumbo, 2009) for its use in the

assessment of online programmes, we encounter:

Tyler’s Objective Model, Stake´s Respondent

Assessment Model, Scriven’s Goal-free Assessment

Model, Kirkpatrick’s Four Level Assessment Model,

Stufflebeam’s CIPP Model and Pérez Juste’s

Integrated Assessment Model.

When it comes to the models developed to assess the

quality of online education, Rubio (2003) divides

them in two types, which, though different, can be

complementary:

3.1 Models with a Partial Approach

These models are focused on the following

assessments:

a) Models focused on assessing the educational

activity

These models are focused on assessing a

particular online educational action, such as a course

or a programme. The purpose of this assessment is

based on three main aspects: verification of the

degree of fulfilment of the educational goals, the

improvement of the educational action itself and the

determination of the return of the investment (Rubio,

2003). The assessment should be applied to all the

elements of the educational action. According to

García Aretio (2014), among others, it is important

to assess the following aspects of the said action:

educational goals, contents, activities,

documentation and materials, the activity of the

online teacher, online methodology, technological

environment (virtual platform).

Nevertheless, we encounter models for the

assessment of online educational actions which

present an approach differing from the one presented

by the aforementioned author (OLC, 2002;

Rekkedal, 2006; Attwell, 2006; Díaz-Maroto, 2009;

Lam & McNaught, 2007; University of Wiscosin,

2008; Giorgetti et al., 2013; Ajmera &

Dharamdasani, 2014; Marshall & ,

Mitchell 2006).

b) Models focused on assessing the materials for

online education

These models are focused on determining to

what extent the materials have characteristics that

are considered desirables and that have been

specified based on previously established criteria

(Opdenacker et al., 2007; Morales, 2010; Fernández-

Pampillón et al., 2013). In general terms, these

models indicate different contextual dimensions that

should be taken into consideration when it comes to

assessing or designing teaching materials for online

education programmes. Among other dimensions,

we would like to highlight: the suitability in terms of

the receivers of the programme, the coherence of the

curriculum, the pedagogical and graphic design, the

quality of the contents, the suitability of the learning

activities, the facility of use, the style and language

used and the flexibility and efficiency.

c) Models focused on assessing virtual platforms

These models are focused on assessing the quality of

the virtual platform used in the implementation of

the online programme (ISO/IEC 9126:2000;

Zaharias & Poylymenakou, 2009; Giannakos, 2010;

Al-Ajlan, 2012; Abdulaziz et al., 2014). A more

detailed analysis of the models proposed by the

aforementioned authors shows that, in general terms,

the assessment of a virtual platform is carried out by

analyzing different dimensions of its quality, such

as, administrative tools, tools for the course

management by users, synchronous and

asynchronous communication tools, assessment,

monitoring and self-assessment tools and

compliance with standards.

3.2 Models with a Global Approach

These models includes two kind of models:

a) Models and/or standards of total quality.

These systems include standards, ISO norms and

assessment models of TQM (Total Quality

Management). Currently, work is carried out in

order to introduce TQM in online education. García

Aretio (2014) states that a large share of the quality

proposals and quality models for online education is

based on the TQM model, as they are focused,

mainly, on customer satisfaction. The customer

satisfaction, in turn, depends on the continuous

improvement, measurements and utmost attention to

processes, teamwork and individual responsibility.

Regarding this point, apart from the existing ISO

norms and quality standards (ISO/IEC 19796-

1:2005, CWA 15660:2007, CWA 15661:2007,

UNIQUe, EFMD CEL, UNE 66181:2012, PAS

1032-1, BP Z 76-001, BCTD Quality Mark, ICT

Mark Standard, NADE's Quality Standards for

Distance Education), we can highlight the model

designed by the European Foundation for Quality

Management (EFQM) and the Balanced Scorecard

Model, as confirmed by Ehlers (2012). This author

states that more than 600 models used across Europe

were encountered within the project titled “European

Quality Observatory carried out in 2005. The most

widely used were the following: ISO norms, EFQM

model, Balanced Scorecard Model and the SCORM

standard.

b) Models based on benchmarking practice.

The purpose of these assessment models is to

identify the key factors that lead online programmes

to success. Recently, we can observe that the

relevance of benchmarking in online education is

rapidly growing, as confirmed by various authors

(Devedžić et al., 2011; Keppell et al., 2011; Op de

Beeck et al., 2012; Marciniak, 2015, 2017) and

different benchmarking projects, such as BENVIC,

CHIRON, ELTI, ACODE, MASSIVE, MIT90s,

PICK&MIX, OBHE, OpenECB, eMM, E-

xcellence+, SEVAQ+ and others. Among these

projects we encounter the BENVIC project

(Benchmarking of Virtual Campus) focused on the

development and application of assessment criteria

in order to promote quality standards in online

education in particular and distance learning in

general. The main areas or dimensions of online

education taken into consideration are: institutional

basis and mission when it comes to student service,

learning resources, teacher support, assessment,

accessibility, effectiveness (related to the financial

aspects), technological resources and institutional

execution.

Each of the aforementioned models seeks to

assist universities to improve the quality of their

online education. Nevertheless, these models do

present certain limitations, as great majority of them

do not duly focus on the assessment of the

educational programmes which the education is

based on. The dimensions and indicators proposed

by these models rarely respond to the need of

assessing the pedagogical-didactic and technological

elements of the programme, as well as its planning,

application and results. To fill this void, the project

will propose an integrated model that allows to

assess in a complex manner all of the

aforementioned elements of the programme, while

also allowing to carry out its ongoing assessment.

4 METHODOLOGY

According to Hernández et al. (1991), a research can

include different types of study methods at the

various stages of its development. Accordingly, in

this research we encounter:

4.1 In the Area of Bibliography

• Bibliographical and documentary analysis of

online higher education and higher online education

programmes. The main emphasis is set on the

elements that compose the said programmes, as well

as on the assessment of their quality.

• Documentary study regarding different

initiatives designed worldwide to assess the

quality of online education in order to identify

which of them provide indications and

suggestions regarding the process of self-

assessment of higher online education

programmes. The said initiatives are:

standards, models and tools designed by

researchers, universities and accreditation

organizations.

4.2 In the Area of Empirical Research

• Validation of the model by international expert

judgment.

• Quantitative validity of the model by

calculating the facial validity index, the

contents validity index and the interjudge

reliability index for all the indicators

composing the model.

• The qualitative validation of the model.

• Discussion group.

• Data triangulation.

• Pilot application of the model.

5 OUTCOMES

5.1 In the Area of Bibliography

The bibliographical revision shows that online

modality requires the educational program to be

composed of all the relevant pedagogical and

technological elements such as: program

justification, program objectives, student profile,

thematic contents, online teacher profile, learning

activities, teaching resources and materials, teaching

strategies, learning assessment strategies, tutoring

and virtual classroom. These elements describe the

quality of online programme itself, and for this

reason should be assessed constantly in order to

improve it.

The results of the bibliographical analysis

regarding assessment of the quality of online

programmes show that, apart from the elements of

the programme, the assessment of online

programmes should include the assessment of all the

stages the programme goes through during its

existence, that is, of its initial, development and final

stage. The purpose is to review what have been

planned, organized and prepared in order to know

whether the programme can be launched, as well as

how the programme has been developed and, finally,

whether the objectives of the programme have been

reached (measuring of the effects).

The results of the analysis of the scope of the

standards, rules and instructions for the self-

assessment of online programmes show that, even

though we encounter different standards applied to

virtual education, none of them has is focused on the

self-assessment of online higher education

programmes.

Once the main part of the existing guides and

tools to assess and improve online education has

been analysed, we can conclude that there is a

limited number of tools for the self-assessment of

this kind of education. This scarcity of literature

appears both at a national and international level.

Moreover, it can be concluded that there is no tool

that allows to assess both the quality of the

programme itself, as well as of each of the stages of

its existence (initial, development and final stage).

Different models seek to provide a response to

the issue of the assessment of the quality of virtual

higher education programmes. Some of them have

been adapted from models applied to traditional

education, while others developed with the purpose

of assessing virtual higher education programmes.

Nevertheless, so far none of the said models

manages to satisfy on its own all the educational

needs of the said programmes. Among these needs,

we encounter the need for the application of

different dimensions and indicators allowing the

persons in charge of the programme and/or the

universities to measure the quality of the programme

itself and of each of the three stages of its existence

(initial, development and final stage) in order to

verify the degree and the quality with which the

programme has been planned and implemented, as

well as to evaluate the results of the programme,

according to the set goals.

5.2 In the Area of Empirical Research

The documentary and bibliographical revision has

made it possible to determine the variables of the

first draft of our model and its dimensions, as well as

to determine its operative definitions presented in

table 1.

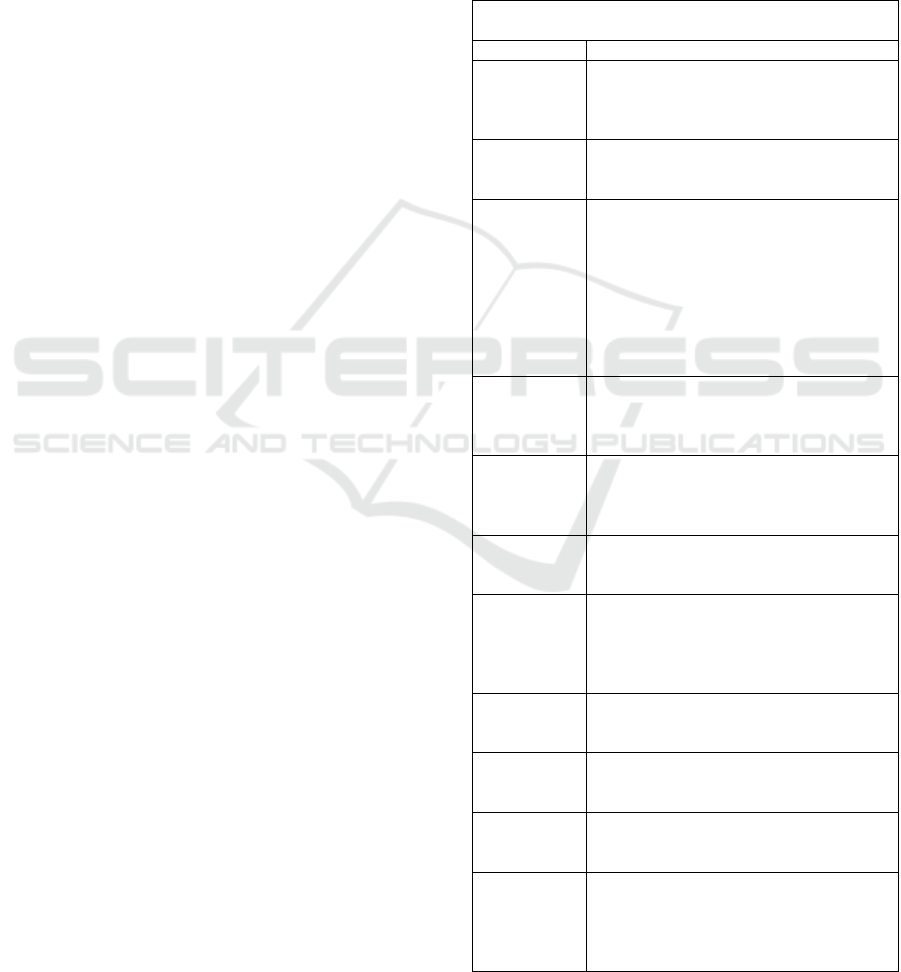

Table 1: Operative definitions of the dimensions o the

model for the self-assessment of higher education online

programmes.

Variable 1: The assessment of the quality of the online

education program itself

Dimension Operative definition

Online

Program

Justification

It determines the reason for the existence

of the online program, by making

reference to why the student should

participate in the program.

Online

program

objectives

It describes the objectives that are aimed

to be reached through the online program.

Access and

graduation

profile

Access profile should be understood as a

set of knowledge, skills and attitudes that

the person willing to take part in the

program should possess in order to

complete it in the most successful way

possible. Graduation profile defines the

skills that the student should develop and

acquire thanks to participating in the

program.

Thematic

contents of

the online

program

It presents the themes and topics that

constitute the program in order for the

student to address, in general terms, the

issue presented by the virtual program.

Learning

activities

It refers to the different tasks through

which the teacher applies teaching

methods, strategies and techniques in

order to facilitate the learning process.

Online

teacher

profile

A set of particular features that

characterize the person who teaches the

virtual program.

Educational

resources

Any resource that provides the students

with all the necessary information in order

to carry out the learning activities, as well

as the resources used by the teacher in the

teaching process.

Educational

strategies

Strategies and technologies used by the

online teacher in order to support the

teaching-learning processes.

Tutoring Coaching process during the learning

process carried out by the online teacher

through individual attention.

Assessment

of learning

Procedures related to how or whether the

university assesses the student's learning

experience.

Quality of

the virtual

classroom

Technological tools that work as a support

for virtual education, that is, a software

that allows educational contents to be

distributed and to carry out online

educational programmes.

Table 1: Operative definitions of the dimensions o the

model for the self-assessment of higher education online

programmes (Cont.).

Variable 2: Ongoing assessment of the online program

Dimension Operative definition

Initial

assessment

of the

programme

It allows to verify what has been planned,

organized and prepared in order to know

whether the programme can be launched.

The assessment of this stage should be

carried out one week before the planned

start of the programme online.

Processual

Assessment

of the Online

Programme

The second stage of the programme. It

allows to verify how the programme has

been developed. The assessment of this

stage should be carried out in the medium

stage of its realization.

Final

assessment

of the online

programme

The last stage of the programme. It allows

to verify, among others, whether the

educational objectives have been

achieved. The assessment of this stage

should be carried out immediately after

the completion of the online programme.

The first draft of the model was validated by 23

international experts, who validated the model when

it comes to its univocality, suitability and relevance

of each of the indicators composing the model, as

well as the suitability of the calculation formula of

the indicator and the relevance of the evidence

required to assess the degree of its fulfilment.

Based on the results of the said validations, the

quantitative and qualitative validity of the model

was verified. The quantitative validity was verified

by calculating the facial validity index, the contents

validity index and the interjudge reliability index for

all the indicators composing the model. The

qualitative validation of the model was verified by

collecting all the comments made by the experts to

justify their answers, as well as their suggestions for

the improvement of the model.

In general terms, the results of the quantitative

validity show that the model is a tool with good

psychometric properties, that is, that it is valid and

reliable when it comes to the assessment of the

quality of online programmes, given that E:

- Its facial validity with experts is high with an

acceptability index of 0.91;

- The validity of the contents of the model based

on the Lawshed Method modified by Tristán

shows that, in general, the indicators are typical

of theoretical domain as their Global Validity

Index is of 0.92.

- The reliability determined by the Kappa de Fleiss

(k) index shows a global index of k=0,73, which

shows a good concordance among the experts,

according to the Altman classification, under the

five criteria assessed by them.

The results of the qualitative validation of the model

carried out by a group of experts show that all the

proposed indicators were assessed as univocal or

appropriate to the dimensions under which they were

included and relevant to assess higher education

online programmes, with the exception of the

indicator “Variety of Teaching Materials and

Resources” which, according to the experts, does not

affect the quality of the assessed programme.

As for the assessment criteria “Suitability of the

calculation formula”, even though all the formula

were considered appropriate by the experts,

according to their comments, some of them should

be modified in order to improve them. According to

the said comments, the required evidences for some

of the indicators should be reformulated, even

though all of them were considered relevant or

highly relevant.

Once the qualitative validation was completed,

the results were triangulated with the results of the

quantitative validation and specialized literature,

which allowed us to make decisions regarding the

maintenance, modification or removal of an

indicator and, as a result, to create the provisional

model II (second draft) for the self-assessment of

higher education e-learning programmes. According

to the results of the carried out triangulation, the

number of indicators was reduced to a total of 118

(two indicators less than the total number of

indicators of the provisional model I).

The second draft of the model was validated by

two discussion groups: one composed by seven

experts from the Universidad Virtual de la

Universidad de Guadalajara (México), and another

one composed by five Spanish users (students) of

online education. The validation carried out by the

persons participating in the two discussion groups

has allowed us to adjust and improve the model

according to the comments made by them. These

comments, which were incorporated in the model,

were applied to draft the definitive model for the

self-assessment of higher online education

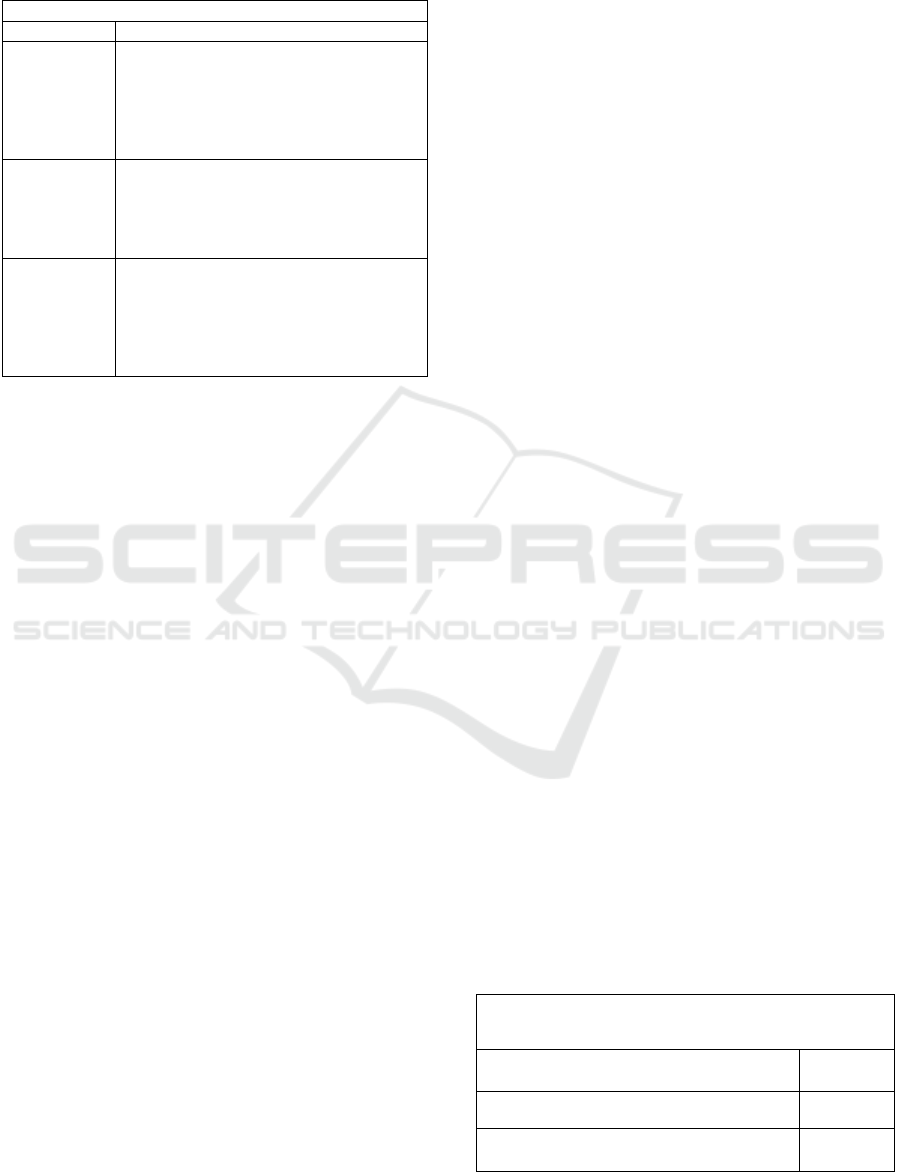

programmes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: The structure of the definitive Model for the Self-

assessment of Higher Online Education Programmes.

Variable 1: The assessment of the quality of the

online education program itself

Dimensions and sub-dimensions

Nr of

indicators

1. Justification of the online programme 3

2. Educational objectives of the online

programme

5

Table 2: The structure of the definitive Model for the Self-

assessment of Higher Online Education Programmes

(Cont.).

Variable 1: The assessment of the quality of the

online education program itself

Dimensions and sub-dimensions

Nr of

indicators

3. Student profile 7

3.1. Access profile 3

3.2. Graduation profile 4

4. Thematic contents/Syllabus of the

online programme

5

5. Learning activities 8

6. Online teacher profile 3

7. Teaching materials and resources 38

7.1. Teaching unit 23

7.1.1. Name of the teaching unit 2

7.1.2. Index of the teaching unit 2

7.1.3. Introduction to the teaching unit 3

7.1.4. Educational objectives of the

teaching unit

2

7.1.5. Development of the contents of

the teaching unit

7

7.1.6. Bibliography of the teaching

unit

3

7.1.7. Other elements of the learning

support

4

7.2: Teaching Guide 11

7.3: Other teaching materials and

resources

4

8. Teaching strategies 3

9. Tutoring 7

10. Assessment of the learning progress 4

11. Quality of the virtual classroom of

the programme

9

Variable 2: Ongoing assessment of the online

programme

12. Assessment of the initial stage of the

programme

4

13. Assessment of the development stage

of the programme

7

14. Assessment of the final stage of the

programme

8

Total indicators 111

6 STAGE OF THE RESEARCH

The definitive model for self-assessment of higher

online education programmes was designed. It was

validated by different audiences and analytical

proceedings. It was also applied in the self-

assessment of four online programmes. However, it

is still necessary to carry out the following activities

in order to increase the utility of the model and

facilitate its implementation at the universities in

different countries:

• To apply the model to a selected sample of

online education programmes offered by

universities in different countries in order to

identify their stable elements and the elements

that can be adjusted to the specific context of

each university.

• To design a “Guide” for the correct

understanding and use of the model by the

persons interested in its use. The “Guide” should

include the self-assessment methodology, the

vocabulary and various illustrative annexes of

the self-assessment process.

• To design and apply the online self-assessment

protocol which would facilitate the said process.

• To design and validate a questionnaire in order to

obtain knowledge regarding the students’

satisfaction with the online program in its

processual and final stages.

7 CONCLUSIONS

It is too early to make final conclusions. It is

necessary to complete the planned research, but the

pilot application of the model in the self-assessment

of four virtual programmes allowed to verify its

potential while assessing the quality of the said

programmes through the detection of their strengths

and weaknesses in order to design an action plan for

their improvement.

REFERENCES

Ajmera, R., Dharamdasani, D. (2014). E-Learning Quality

Criteria and Aspects. IJCTT 12(2), 90-93.

Attwell, G. (2006). Evaluating e-learning A guide to the

evaluation of e-learning. Bremen: Perspective-Offset-

Druck.

Bieliukas, Y., Ornes, C. (2014). Modelos de evaluación de

programas de formación en la modalidad de educación

a distancia: estudio comparativo. Revista de

Tecnología de Información y Comunicación en

Educación 8(2), 55-67.

Chmielewski, K. (2013). Diagnoza stanu kształcenia na

odległość w Polsce i wybranych krajach UE.

Warszawa: Demos Polska.

CNAP (Comisión Nacional de Acreditación de Pregrado).

(2001). Manual para el Desarrollo de Procesos de

Autoevaluación. Santiago de Chile: CNAP.

Devedžić, V., Šćepanović, S., Kraljevski, I. (2011). E-

Learning benchmarking. Methodology and tools

review. Retrieved from http://www.dlweb.kg.ac.rs/

files/DEV1.3%20EN.pdf.

Díaz-Maroto, I. (2009). Formación a través de internet:

evaluación de la calidad. Barcelona: UOC.

Ehlers, U. (2012). Quality Assurance Policies and

Guidelines in European Distance and e-Learning. En:

I. Jung, & C. Latchem (Eds.). (2012). Quality

assurance and accreditation in distance education and

e- learning: models, policies and research, 79-90.

New York: Routledge.

García Aretio, L. (2014). Bases, mediaciones y futuro de

la educación a distancia en la sociedad digital.

Madrid: Sintesis.

Giannakos, M. (2010). The evaluation of an e-learning

web-based platform. In Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education, pp. 433-438. CSEDU ’10. INSTICC Press.

Giorgetti, C., Romero, L., Vera, M. (2013). Design of a

specific quality assessment model for distance

education. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education,10(2), 54-68.

Hilera González, J., Hoya Marín, R. (2010). Estándares de

e-learning: Guía de consulta. Madrid: Universidad de

Alcalá.

ISO/IEC. (2000). ISO/IEC 9126-1 Information technology

— Software product quality — Part 1: Quality model.

Geneva: ISO.

Keppell, M., Suddaby, G., Hard, N. (2015). Ensuring best

practice in technology-enhanced learning

environments. The journal of the Association for

Learning Technology (ALT), 23(1), 1-13.

Lam, P., McNaught, C. (2007). Management of an

eLearning Evaluation Project: The e3Learning Model.

Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 18(3), 365-

380.

Marciniak, R. (2017). Benchmarking como herramienta de

mejora de la calidad de la educación universitaria

virtual. Ejemplo de una experiencia polaca. Revista

EDUCAR, 53(1), 171-207. Doi:

http://educar.uab.cat/article/view/v53-n1-marciniak.

Marciniak, R. (2015). A methodological proposal for

applying international benchmarking to evaluating the

quality of higher virtual education. RUSC.

Universities and Knowledge Society Journal, 12(2),

46-60.

Marshall. S., Mitchell, G. (2006) Assessing sector e-

learning capability with an elearning maturity model.

Proceedings of ALT-C 2006, Edinburgh, UK.

Martínez Mediano, C. (2013). Evaluación de programas.

Modelos y procedimientos. Madrid: UNED.

Marzal, M., Calzada-Prado, J., Vianello, M. (2008).

Criterios para la evaluación de la usabilidad de los

recursos educativos virtuales: un análisis desde la

alfabetización en información. Information Research,

13(4) paper 387.

Morales Morgado, E. (2010). Gestión del conocimiento en

sistemas e-learning, basado en objetos de aprendizaje,

cualitativa y pedagógicamente definidos. Salamanca:

Universidad de Salamanca.

Motz, R. (coord.). (2013). Informe de análisis de

estándares, normas y modelos de capacidad de

madurez relacionados con la calidad y accesibilidad de

la educación virtual. Retrieved from

http://www.esvial.org.

OLC (Online Learning Consortium). (2002). Five Pillars

of Quality Online Education. Retrieved from:

http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/5-pillars/

Opdenacker, L., Stassen, I., Vaes,S., Waes, L., Jacobs, G.

(Eds.). (2007). Manual for the quality assessment of

digital educational material. Belgium: University of

Antwerp.

Op De Beeck, I., Camilleri, A., Bijnens, M. (2012).

Research results on European and international e-

learning quality, certification and benchmarking

schemes and methodologies. Belgium: VISCED

Consortium.

Rekkedal, T. (2006). Criteria for Evaluating Quality in e-

Learning. Norway: NKI.

Rubio Gómez, M. (2003). Enfoques y modelos de

evaluación del e-learning. Revista Electrónica de

Investigación y Evaluación, 9(2), 1-12. Retrieved from

http://www.uv.es/relieve/v9n2/RELIEVEv9n2_1.htm.

Ruhne, V., Zumbo, B. (2009). Evaluation in Distance

Education and E-learning: The Unfolding Model. New

York: Guilford Press.

Veytia Bucheli, M., Chao González, M. (2013). Las

competencias como eje rector de la calidad educativa.

Revista electrónica de Divulgación de la

Investigación, 4. Retrieved from http://portales.

sabes.edu.mx/redi/4/

University of Wiscosin. (2008). Logic Model. Retrieved

from http://www.uwex.edu/ces/pdande/evaluation/

evallogicmodel.html.

Zaharias, P., Poylymenakou, A. (2009). Developing a

Usability Evaluation Method for e-Learning

Applications: Beyond Functional Usability.

International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction

25(1), 75-98.