SME Managers´ Causal Beliefs of the Role of Inter-organizational

Learning in Supply Chain: An Empirical Study

Anne Söderman, Anni Rajala and Anne-Maria Holma

University of Vaasa, Department of Management, Wolffintie 34, 65100 Vaasa, Finland

Keywords: Inter-organizational Learning, Managerial Cognition, Performance, Supply Chain.

Abstract: This study answers the call for empirical research on how managers´ perceive their business network. Here

we focus on SME managers´ reasoning regarding inter-organizational learning. We combine the concept of

managerial cognition with inter-organizational learning (IOL) theories, and study CEOs´ cognitive maps to

find out how managers deduce the effects of learning to their company´s performance and success. The data

consists of interviews of five CEOs of small and medium sized companies (SMEs) representing technology

industries in Finland. The SMEs also represented different positions in their supply chains: one

subcontractor, one hub, and three companies in the middle of the supply chain. Interviews with the CEOs

revealed strong learning intent with effects of relational learning and interactive learning. Learning was

described to occur both upstream and downstream of the supply chain, and the CEOs perceived the effects

of learning to be beneficial both for the relationships and for the individual companies. We contribute to the

knowledge of the role of IOL and CEOs´ cognitive reasoning paths concerning its effects on company´s

performance. By using laddering, a rarely used interview technique in management and organization

research, together with managerial cognitive maps, our study provides also methodological contributions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Inter-organizational relationships (IOR) and

networking have attracted researchers´ interest for

decades. IOR research has argued that competition is

no longer among companies but among supply

chains (e.g. Hernández-Espallardo, Rodríguez-

Orejuela and Sánchez-Pérez, 2010; Wowak,

Craighead, Ketchen and Hult, 2013). Thus, among

scholars there is a growing interest towards inter-

organizational learning and knowledge sharing that

are seen as important avenues for improving

performance in supply chains (e.g. Hernández-

Espallardo et al., 2010). Moreover, it has been

acknowledged that CEOs have a key role in the

development of IORs. This paper aligns with the

growing stream of research in managerial cognitive

processes, sense-making, and network pictures

connected with decision-making in the context of

business networks (Henneberg, Mouzas and Naudé,

2006; Ramos, Henneberg and Naudé, 2012).

However, a number of questions still need to be

investigated. For example, Möller (2010:366) calls

for research on actor´s sense-making processes,

which are seen to be conditioned by the company´s

position and role in the network. Corsaro, Ramos,

Henneberg and Naudé (2011) highlight the need for

more empirical research on the area of how

managers´ perceive their network, and what is the

effect on their actions (also Roseira, Brito and Ford,

2013).

In this paper, we aim to contribute to prior

research by studying managers´ causal beliefs, i.e.

cognitions, concerning the role of learning in supply

networks. Researchers have agreed that managers´

cognitive models are important to strategic decision-

making, and they have an influence on the actors´

behavior (Daniels, Johnson and de Chernatony,

1994; Kor and Mesko, 2013). The cognitions allow

an individual to store information, interpret it, make

decisions and guide his/her actions. However, these

mostly subjectively constructed views are influenced

also by different views of other practitioners and

researchers. Our empirical study addresses SME

managers’ cognitive models of the role of inter-

organizational learning in relation to the

performance and success of the company.

Underlying this interest are assumptions that

cognition is a key factor in purposive social action

and performance (Axelrod, 1976).

SÃ˝uderman A., Rajala A. and Holma A.

SME ManagersÂt’ Causal Beliefs of the Role of Inter-organizational Learning in Supply Chain: An Empirical Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0006492801140120

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (KMIS 2017), pages 114-120

ISBN: 978-989-758-273-8

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Inter-organizational learning (IOL) literature has

confirmed the positive effects of learning on

different performance outcomes, and also confirmed

the important role of learning intent in realization of

IOL. However, prior research of IOL is mainly

focused on relationship and organizational level

studies and there is scarce research focusing on

individual level investigations (Werr and Runsten,

2012), even though prior research has acknowledged

that individuals hold key roles when it comes to

knowledge exchange and learning in IORs. Our

intention is to fill this gap by focusing on SME

managers´ reasoning regarding IOL. More precisely,

we are interested in investigating how IOL emerges

in managers´ knowledge structures, and how

managers see the effects of IOL on the company´s

performance.

The paper has several contributions. Firstly, it

increases knowledge about the role of IOL, focusing

particularly on relationship learning and interactive

learning in supply chain context. Secondly, this

paper shows the CEOs´ cognitive reasoning paths

concerning network relationships and their strategic

and operational effects on company´s performance.

In addition, our study has methodological

contributions. We used laddering, a rarely used

interview technique in management and organization

research, and managerial cognitive maps, which are

seldom applied in business relationship research.

The paper is structured in the following way.

The next section presents a brief literature review.

Second, the methodological premises of the study

are explained, following the presentation of the main

findings. Finally, we conclude the study and discuss

its managerial implications.

2 MANAGERIAL COGNITION

AND COGNITIVE MAPS

Due to the growing complexity in business

environment, managers employ their internal

knowledge structures and develop new structures in

order to make sense of their environment (Day and

Nedungadi, 1994). Sense-making is a complex

individual and also collective phenomenon. It refers

to an actor´s ability to perceive, interpret, and

construct meaning of the world around him/her

(Weick, 1995). Through sense-making, actors

construe individual cognition, or ways of reasoning

about current or emerging issues and phenomena.

Much of interest has been paid to interpretation

and sense-making of events, problem-solving, and

decision-making. Underlying this interest in

studying management and organization cognition is

a general agreement among researchers that

cognition is a key factor in purposive social action,

performance (Axelrod, 1976), and managers´

decision-making (Daniels et al., 1994; Eden and

Spender, 1998; Huff, 1990; Walsh, 1995). Cognition

refers to individual, group, or organization

phenomena related to knowing, i.e. questions

relating to the types or use of human knowledge.

Cognitive maps are seen as representations of

relevant characteristics in the management of

companies, internalized through the thinking of

managers or other involved actors (Huff, 1990;

Brown, 1992). Two basic elements of cognitive

maps are concepts and causal beliefs. Concepts

define some aspect of the issue under analysis, while

causal beliefs describe the relationships linking

concepts within maps (Axelrod, 1976).

Recently, the concept of network pictures has

been widely used to study phenomena related to

business networking and actors´ views about their

surrounding networks. However, there are still

different interpretations of the concept and how to

understand its contents (Ramos et al., 2012:952).

Therefore, in this study we use the concept of

managerial cognition.

3 INTER-ORGANIZATIONAL

LEARNING

Prior research has viewed inter-organizational

learning (IOL) from different perspectives. One of

the perspectives that is widely used in business

relationship research (see e.g. Cheung, Myers and

Mentzer, 2011; Jean, Kim and Sinkovics, 2012) is

relationship learning. Selnes and Sallis, 2003 (p. 86)

define relationship learning as “a joint activity

between a supplier and a customer in which the two

parties share information, which is then jointly

interpreted and integrated into shared relationship-

domain-specific memory that changes the range or

likelihood of potential relationship-domain-specific

behavior”. Relationship learning involves three sub

processes: information sharing, joint sense-making,

and knowledge integration (Selnes and Sallis, 2003).

Knowledge sharing is required in order to coordinate

collaboration and achieve operational efficiency,

however, each organization has different ability to

acquire information and thus joint sense-making

varies across organizations. In order to complete

IOL process, acquired knowledge is integrated into

relationship-specific memory (Selnes and Sallis,

2003), which is essential in bringing the new

knowledge into use and delivering the expected

performance benefits (Kohtamäki and Partanen,

2016). Another widely used perspective of IOL is

interactive learning, which also occurs between two

companies and is based on an assumption that

acquisition of new knowledge occurs through

interaction between members from different

organization (Huang and Chu, 2010; Lane and

Lubatkin, 1998). Interactive learning view holds

that knowledge is shared and transferred at the

relationship level, but assimilation or interpretation

of the acquired knowledge occurs within

organizations, which also means that applying

knowledge in practice also occurs within

organizations. Moreover, Huang and Chu (2010)

state that interactive learning can be viewed as a

catalyst for internalized learning, while relationship

learning perspective states that learning occurs at the

relationship level.

In order to actively learn from supplier

relationships, a firm needs to have learning intent,

which is a firm’s tendency to treat cooperation as a

learning opportunity (Fang, Fang, Chou, Yang and

Tsai, 2011; Huang and Chu, 2010; Johnson and

Sohi, 2003). IOL requires resources and might have

high costs and thus not all companies intend to learn

from their business relationships, or some companies

maintain purely transactional relationships without

any learning intent (Huang and Chu, 2010).

Therefore, learning intent can be seen as a kind of

strategic decision to invest resources in learning

(Johnson and Sohi, 2003). Further, it is argued that

managers with strong learning intent would attempt

to remove barriers of IOL, and would more likely

invest resources to establish a formal system or

routine for the purpose of learning (Fang et al.,

2011). Thus, prior research has confirmed the role of

learning intent as an important antecedent of IOL

(e.g. Liu, 2012). Moreover, prior studies have

confirmed the positive performance effects of IOL

on relationship performance (e.g. Johnson and Sohi,

2003; Selnes and Sallis, 2003), on operational

performance (e.g. Cheung, Myers and Mentzer,

2010; Hernández-Espallardo et al., 2010), on market

performance (e.g. Chang and Gotcher, 2010; Jean,

Sinkovics and Kim, 2010), and on innovation

performance (e.g. Chen, Lin and Chang, 2009; Fang

et al., 2011).

In sum, prior research has shown the positive

effects of IOL on performance and has stated that

learning intent is an important antecedent of IOL. As

well as prior research has emphasized the important

roles of individuals and their behavior in IOL (Werr

and Runsten, 2012). However, the IOL research has

mainly focused on organizational and relationship

level investigations and there is a need for further

research of the roles of individuals in IOL processes

(see e.g. Werr and Runsten, 2012). Thus, the current

paper focuses on the role of IOL in managers’

knowledge structures, i.e. cognition, and further in

their cognition of doing successful business and

creating competitive advantages. In addition, we

focus on how managers perceive the effect of IOL

on their business.

4 METHODOLOGY

To collect data, we conducted open-ended in-depth

interviews with the CEOs of five SME companies

representing technology industries in Finland. The

SMEs were selected using purposeful sampling

(Eisenhardt, 1989) to obtain data, which is rich of

information. We selected companies in different

positions in different supply chains (table 1) to

obtain and contrast the views from the buyer and the

supplier companies. Three of the SMEs were “in the

middle” of their supply chain and, thus, had both

upstream suppliers and downstream customers (B,

C, D). One of the SMEs was a subcontractor (A),

and one of the SMEs was a hub company (E), the

former having mainly upstream customers, and the

latter mainly downstream customers.

During the interviews, respondents were asked to

describe key elements of their thinking about the

company´s profitable performance. Laddering,

which is rarely used in management and

organization research (Bourne and Jenkins, 2005:

411; for example Brown, 1992; Langerak, Peelen

and Nijssen, 1999), was used as an interview

method. Laddering involves tailored interviewing

with repeatedly asked probing questions, such as

“how does it affect”, “why is it important”, which

represents an interviewing protocol known

laddering-down to antecedent conditions and

laddering-up to anticipated effects (Bourne and

Jenkins, 2005; Brown, 1992; Grunert and Grunert,

1995). The interviews lasted between 50 and 90

minutes, and were audio-recorded and transcribed

with the permission of the interviewees.

The data were analyzed applying content

analysis techniques (Miles and Huberman, 1992)

and cognitive mapping with Decision Explorer®

Software. Consequently, we could present separate

cognitive maps of each interview for further

analysis. Cognitive mapping has been widely used in

the field of management and organization research

(for example Calori, Johnson and Sarnin, 1992;

Daniels et al., 1994; Jenkins and Johnson, 1997), but

it is very rare especially in the research on business

relationships. Cognitive mapping techniques refer to

methods that are used to explore subjective beliefs,

i.e. the structure and content of individuals´

cognition (mental models) of given issues (Axelrod,

1976; Spender, 1998), and the way in which

individuals organize their thoughts. These visual

representations (Chaney, 2010; Clarke and

Mackaness, 2011) helped the researchers to work

through analysis process identifying important issues

and to discuss them further. The coding and the

cognitive maps were then compared. During the

analysis, the information was processed by moving

back and forth between the data (Dubois and Gadde,

2002), the framework of the study, and the tentative

findings (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007).

5 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

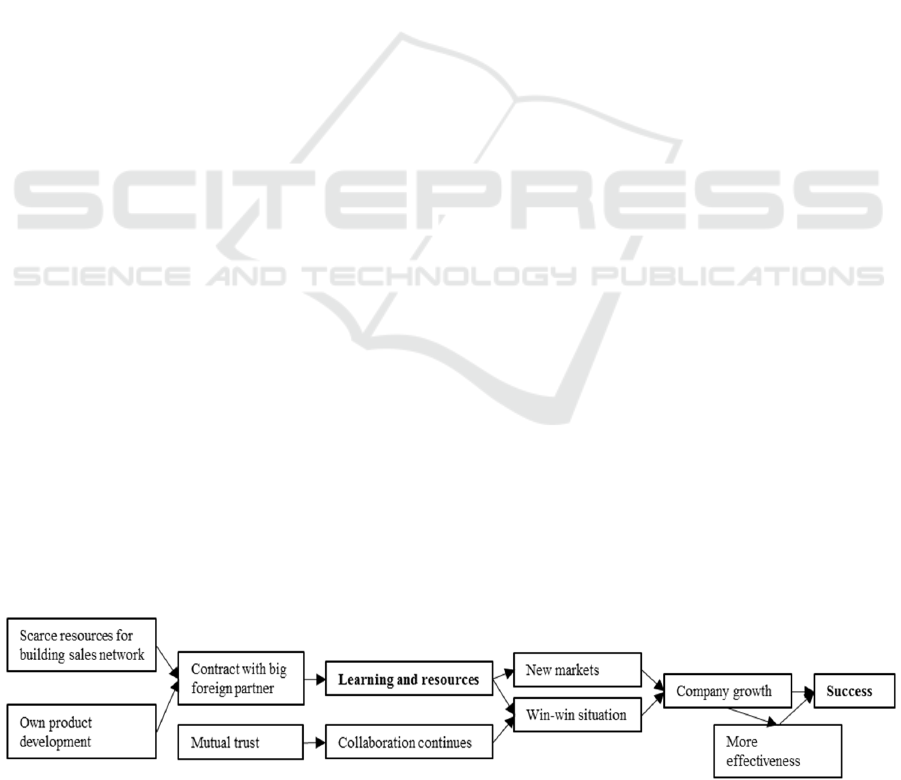

The CEOs perceived IOL to be important for the

company’s success, showing thus strong learning

intent (Fang et al., 2011). Figure 1 demonstrates a

simplified example of the cognitive map, i.e. how

IOL emerges in one of the CEOs (D; see table 1)

knowledge structures, introducing the antecedents

for learning and effects of learning for the SME he

represented. The appearance of IOL in CEO’s

cognitive map reflects the learning intent of a

company.

According to the CEO (D) it was “impossible for

the company (D) to build an international sales

network without the resources and connections

provided by a large partner”. In order to attract and

convince this large partner about company D’s

capabilities, the company D had made strong

investments in product development. These

investments proved to be fruitful, and a contract was

established between company D and the large

partner. In their relationship, these partner

companies shared information, and combined their

knowledge to learn aiming to develop the business

further. Learning, mutual trust, and continuing

relationship resulted in win-win situation for the two

companies. Further, new markets and growth of the

business were materialized, which was experienced

as a success for the company D.

Generally, resources were allocated to common

workshops and product development (Fang et al.,

2011). Typically, the CEOs referred to interaction,

open dialogue and joint activities (Selnes and Sallis,

2003; Huang and Chu, 2010) as the means of

learning, and trust was seen as an important pre-

requisite for learning (Håkansson, Havila and

Pedersen, 1999). Regular discussions and workshops

as well as meetings for product or service

development were discovered as platforms for open

information sharing, joint sense-making, and

knowledge integration between companies in their

relationhips (Selnes and Sallis, 2003).

Both relationship learning and interactive

learning were discovered in CEOs´ perceptions;

learning was suggested to have been applied to

develop activities and resources to benefit the

company itself and its cooperating partners, specific

relationships (relationship learning), and the

company’s processes (interactive learning).

Relationship learning was found to have an

influence on, for example, customer satisfaction,

relationship continuity, (supplier chain) efficiency

and effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and quality

improvement. The perceived learning was also seen

to have an impact on the company’s growth, brand

image, internationalization, profitability and

competitiveness. However, for example profitability

and competitiveness, albeit primarily connected to

the focal company, can have effects on both sides of

a buyer-supplier relationship.

The company´s position in the supply chain was

noticed to have an effect on CEOs´ cognitive models

related to IOL, although interactive learning and

learning effects were also discussed by all the CEOs.

The CEO of the hub company (E) at the end of the

supply chain reflected more to relationship learning

related issues, meanwhile at the other end of the

Figure 1: A simplified visualization of a CEO’s cognitive map.

Table 1: Selected examples of CEOs’ perceptions of learning and its effects.

supply chain, the CEO´s (A) perceptions were

related more to interactive learning. However, joint

activities and IOL was described occurring both in

upstream and in downstream supply chain. As well

as customers and suppliers both can be regarded as

sources of information and new knowledge. The

supplier responded to the customer’s complaining by

suggesting improvements, which were then planned

and realized in cooperation. Respectively, when the

customer demanded better quality and fluent

processes, the supplier developed them together with

the customer. The supplier was also able to learn

through the requirements of the customer’s

customer, and adapt its services accordingly.

The motivation for companies C, D and E to

build relationships was strategic meanwhile

companies A and B built their relationships mainly

through transactions (see table 1). We found that in

these strategically important relationships (C, D and

E), the CEOs referred more often, and discussed

more broadly issues related to relationship learning

and the effects of learning than in mainly

transaction-oriented relationships (A and B).

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, using laddering techniques we

interviewed the CEOs of five SMEs in technology

companies in Finland to analyze the CEOs´

perceptions of inter-organizational learning. We

applied cognitive mapping to analyze how managers

construe the effects of learning to their company’s

performance and success. Due to the limitation in

the length of the paper, we provided a simplified

example of a CEO’s cognitive map, and an example

how each of the five companies´ CEOs perceived

learning, and the effects of learning on the

company’s performance. We noticed that the CEOs

invested resources to enhance learning, and we also

registered a number of positive learning outcomes.

This paper contributes to the IOL research by

showing that the existence of IOL in CEO’s

cognitive map reflects a company’s learning intent.

Moreover, we found that different types of learning

emerge in supply relationships in accordance with its

strategic importance.

Prior research (e.g. Axelrod, 1976; Huff, 1990)

has confirmed that cognitive maps affect decision

making. Therefore, we recommend that managers

should be aware of their cognitions, personally as

well as understanding that cognitions may often

differ, for example between team or board members

in a company, or between different network partners.

In supply chain relationships, learning is expected to

result also in changes in managers´, or other related

persons´ cognitive maps, as an outcome of

information sharing and mutual sense-making. Since

IOL has proofed to be an important source of

competitive advantages (Spekman, Spear and

Kamauff, 2002), managers should consider in which

position IOL emerge in their cognitive maps of

company performance and if there is room for

improvements.

The findings of the paper indicate that strategic

importance has an influence on the type of learning

that exists in managers´ cognitions. Strategic

importance can also reflect dependence between the

customer and the suppliers. Thus, future research

could investigate the effects of dependence on

managers´ cognitions concerning IOL. Moreover, it

would be interesting to compare cognitions of

managers in matcher dyadic and triadic network

relationships.

REFERENCES

Axelrod, R. (Ed.) 1976. Structure of decision. The

cognitive maps of political elites. Princeton. New

Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Bourne, H., Jenkins, M., 2005. Eliciting managers´

personal values: An adaptation of the laddering

interview method. Organizational Research Methods,

8(4), 410–428.

Brown, S., 1992. Cognitive mapping and repertory grids

for qualitative survey research: some comparative

observations. Journal of Management Studies, 29(3),

287–307.

Calori, R., Johnson, G., Sarnin, P., 1992. French and

British top managers´ understanding of the structure

and the dynamics of their industries: a cognitive

analysis and comparison. British Journal of

Management, 3(2), 61–78.

Chaney, D., 2010. Analyzing mental representations: The

contribution of cognitive maps. Recherche et

Applications en Marketing, 25(2), 93–115.

Chang, K.-H., Gotcher, D., 2010. Conflict-coordination

learning in marketing channel relationships: The

distributor view. Industrial Marketing Management,

39(2), 287–297.

Chen, Y.-S., Lin, M.-J., Chang, C.-H., 2009. The positive

effects of relationship learning and absorptive capacity

on innovation performance and competitive advantage

in industrial markets. Industrial Marketing

Management, 38(2), 152–158.

Cheung, M.-S., Myers, M., Mentzer, J., 2010. Does

relationship learning lead to relationship value? A

cross-national supply chain investigation. Journal of

Operations Management, 28(6), 472–487.

Cheung, M.-S., Myers, M., Mentzer, J., 2011. The value of

relational learning in global buyer-supplier exchanges:

A dyadic perspective and test of the pie-sharing

premise. Strategic Management Journal, 32(10),

1061–1082.

Clarke, I., Mackaness, W., 2001. Management “intuition”:

An interpretative account of structure and content of

decision schemas using cognitive maps. Journal of

Management Studies, 38(2), 147–172.

Corsaro, D., Ramos, C., Henneberg, S., Naudé, P., 2011.

Actor network pictures and networking activities in

business networks: An experimental study. Industrial

Marketing Management Special Issue, 40(6), 919–

932.

Daniels, K., Johnson, G., de Chernatory, L., 1994.

Differences in managerial cognitions of competition.

British Journal of Management, 5(1), 21–29.

Day, G., Nedungadi, P., 1994. Managerial representations

of competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing,

58(2), 31–44.

Dubois, A., Gadde, L.-E., 2002. Systematic combining:

and abductive approach to case research.

Journal of

Business Research, 55(7), 553–560.

Eden, C., Spender, J.-C., 1998. Managerial and

organizational cognition. Theory, methods and

research. London: Sage Publications.

Eisenhardt, K., Graebner, M., 2007. Theory building from

cases. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Fang, S.-R., Fang, S.-C., Chou, C.-H., Yang, S.-M., Tsai,

F.-S., 2011. Relationship learning and innovation: The

role of relationship-specific memory. Industrial

Marketing Management, 40(5), 743–753.

Grunert, K., Grunert, S., 1995. Measuring subjective

meaning structures by the laddering method:

Theoretical considerations and methodological

problems. International Journal of Research in

Marketing, 12(3), 209–225.

Henneberg, S. C., Mouzas, S., Naudé, P., 2006. Network

pictures – concepts and representation. European

Journal of Marketing, 40(3/4), 408–429.

Hernández-Espallardo, M., Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.,

Sánchez-Pérez, M., 2010. Inter-organizational

governance, learning and performance in supply

chains. Supply Chain Management: An International

Journal, 15(2), 101–114.

Huang, Y.-T., Chu, W., 2010. Enhancement of product

development capabilities of OEM suppliers: inter- and

intra-organisational learning. Journal of Business &

Industrial Marketing, 25(2), 147–158.

Huff, A., 1990. Mapping strategic thought. Chichester:

John Wiley & Sons.

Håkansson, H., Havila, V., Pedersen, A.-C., 1999.

Learning in Networks. Industrial Marketing

Management, 28(5), 443–452.

Jean, R.-J., Kim, D., Sinkovics, R., 2012. Drivers and

Performance Outcomes of Supplier Innovation

Generation in Customer-Supplier Relationships: The

Role of Power-Dependence. Decision Sciences, 43(6),

1003–1038.

Jean, R.-J., Sinkovics, R., Kim, D., 2010. Drivers and

Performance Outcomes of Relationship Learning for

Suppliers in Cross-Border Customer–Supplier

Relationships: The Role of Communication Culture.

Journal of International Marketing, 18(1), 63–85.

Jenkins, M., Johnson, G., 1997. Entrepreneurial intentions

and outcomes: a comparative causal mapping study.

Journal of Management Studies, 34(6), 895–920.

Johnson, J., Sohi, R., 2003. The development of interfirm

partnering competence: Platforms for learning,

learning activities, and consequences of learning.

Journal of Business Research, 56(9), 757–766.

Kohtamäki, M., Partanen, J., 2016. Co-creating value from

knowledge-intensive business services in manufactur-

ing firms: The moderating role of relationship learning

in supplier–customer interactions. Journal of Business

Research, 69(7), 2498–2506.

Kor, Y., Mesko, A., 2013. Dynamic managerial

capabilities: configuration and orchestration of top

executives´ capabilities and the firm´s dominant logic.

Strategic Management Journal, 34(2), 233–244.

Lane, P., Lubatkin, M., 1998. Relative absorptive capacity

and interorganization learning. Strategic Management

Journal, 19(5), 461–477.

Langerak, F., Peelen, E., Nijssen, E., 1999. A laddering

approach to the use of methods and techniques to

reduce the cycle time of new-to-the-firm products.

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(2),

173–182.

Liu, C.-L., 2012. An investigation of relationship learning

in cross-border buyer-supplier relationships: The role

of trust. International Business Review, 21(3),

311–327.

Miles, M., Huberman, A., 1992. Qualitative Data

Analysis. Sage: London.

Möller, K., 2010. Sense-making and agenda construction

in emerging business networks – How to direct radical

innovation. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(3),

361–371.

Ramos, C., Henneberg, S., Naudé, P., 2012.

Understanding network picture complexity: an

empirical analysis of contextual factors. Industrial

Marketing Management, 41(6), 951–972.

Roseira, C., Brito, C., Ford, D., 2013. Network pictures

and supplier management: An empirical study.

Industrial Marketing Management, 42(2), 234–247.

Selnes, F., Sallis, J., 2003. Promoting relationship

learning. Journal of Marketing, 67(3), 80–95.

Spekman, R., Spear, J., Kamauff, J., 2002. Supply chain

competency: learning as a key component. Supply

Chain Management: An International Journal, 7(1),

41–55.

Spender, J.-C., 1989. Industry Recipes: An Enquiry into

the Nature and Sources of Managerial Judgement.

Blackwell. Oxford.

Walsh, J., 1995. Managerial and organizational cognition:

notes from a trip down memory lane. Organization

Science, 6(3), 280–321.

Weick, K., 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand

Oaks, CA:Sage.

Werr, A., Runsten, P., 2012. Understanding the role of

representation in interorganizational know-ledge

integration: A case study of an IT outsourcing project.

The Learning Organization, 20(2), 118–133.

Wowak, K., Craighead, C., Ketchen, D, Hult, G., 2013.

Supply chain knowledge and performance: A meta-

analysis. Decision Sciences, 44(5), 843–875.