A Simple and Practical Sensorimotor EEG Device for Recording in

Patients with Special Needs

Stefan Ehrlich

1

, Ana Alves-Pinto

2

, Ren

´

ee Lampe

2,3

and Gordon Cheng

1

1

Chair for Cognitive Systems, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Technical University of Munich,

Karlstr 45/II, 80333 Munich, Germany

2

Research Unit for Paediatric Neuroorthopaedics and Cerebral Palsy of the Buhl-Strohmaier Foundation, Orthopedic

Department, Klinikum Rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Ismaninger Str. 22, 81675 Munich, Germany

3

Markus W

¨

urth Stiftungsprofessur for Cerebral Palsy and Paediatric Neuroorthopaedics, Technical University of Munich,

Munich, Germany

Keywords:

Electroencephalography (EEG), Portable EEG, Sensorimotor Rhythms, Event-related (de-)Synchronization

(ERD/ERS), Sensorimotor Disorders, Cerebral Palsy (CP).

Abstract:

In studies involving patients with special needs, the use of electroencephalography (EEG) recordings is among

the most delicate measurement modalities. The quietness needed and the long preparation time can be chal-

lenging especially in young ages. Furthermore, the invasive appearance of the instrumentation involved is not

appealing and can raise distrust in patients. We developed a customized EEG device which adresses these

issues by merging commercially available EEG hardware with an unobtrusive headphones design. The result-

ing device has very short preparation times, non-clinical appearance, and delivers adequate data quality with

respect to recording of sensorimotor rhythms. Our device was employed in a study investigating sensorimotor-

related brain activity in adolescents and adults with cerebral palsy (CP) conducted at a day-care center. Ex-

perimenters reported convenient data collection and overall acceptance of the system among patients. The

changes in sensorimotor rhythms over time during a hand motor task meet the observations described in the

literature, supporting the functionality of our EEG device for the assessment of sensorimotor-related measures

of brain activity in patients with sensorimotor disorders of neuronal origin.

1 INTRODUCTION

In clinical studies, researchers need to be aware not

only of the underlying (neuro)physiology specific to

a clinical group but also of how experimental data

can be successfully collected in patients with special

needs (Vuckovic et al., 2015). This is particularly ev-

ident in patient groups involving children or elderly

population, but also in individuals suffering from be-

havioral and developmental disorders, such as autism,

cerebral palsy (CP), and sensorimotor disorders in

general. Several issues are common among these pa-

tient groups: (1) reduced attention span and highly

fluctuating concentration (2) impaired motor function

and consequent inability to execute some experimen-

tal tests, (3) cognitive and sensory impairment (4) mo-

toric restlessness and sudden involuntary movements

typical for dyskinetic cerebral palsy, (5) worry about

obtrusive measurement equipment that is associated

to earlier clinical examinations and negative and un-

pleasant experiences, especially in patients that went

through long medical treatment.

In most cases a careful tradeoff between what the

patients can bear and the amount, type as well as

quality of collected data has to be made. In this re-

gard, whilst electroencephalography can be a valu-

able primary or complementary experimental modal-

ity, it is often declined as: (1) EEG equipment used

in experimental studies can look obtrusive and raise

distrust amongst patients. Researchers risk there-

fore that patients decline to participate in the study.

(2) Proband preparation exceeds at least 15 minutes

which is above endurance of many individuals from

above mentioned patient groups. (3) The data col-

lected can be strongly affected by different types of

artifacts (e.g. muscular interference due to restless-

ness) and cannot be considered in the evaluation.

When looking at commercially available EEG

systems, currently the market offers four established

categories: (I) medical systems for clinical monitor-

ing and diagnosis, (II) scientific systems for experi-

mental research and Brain-Computer Interfaces, (III)

Ehrlich S., Alves-Pinto A., Lampe R. and Cheng G.

A Simple and Practical Sensorimotor EEG Device for Recording in Patients with Special Needs.

DOI: 10.5220/0006559100730079

In Proceedings of the 5th Inter national Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics (NEUROTECHNIX 2017), pages 73-79

ISBN: 978-989-758-270-7

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

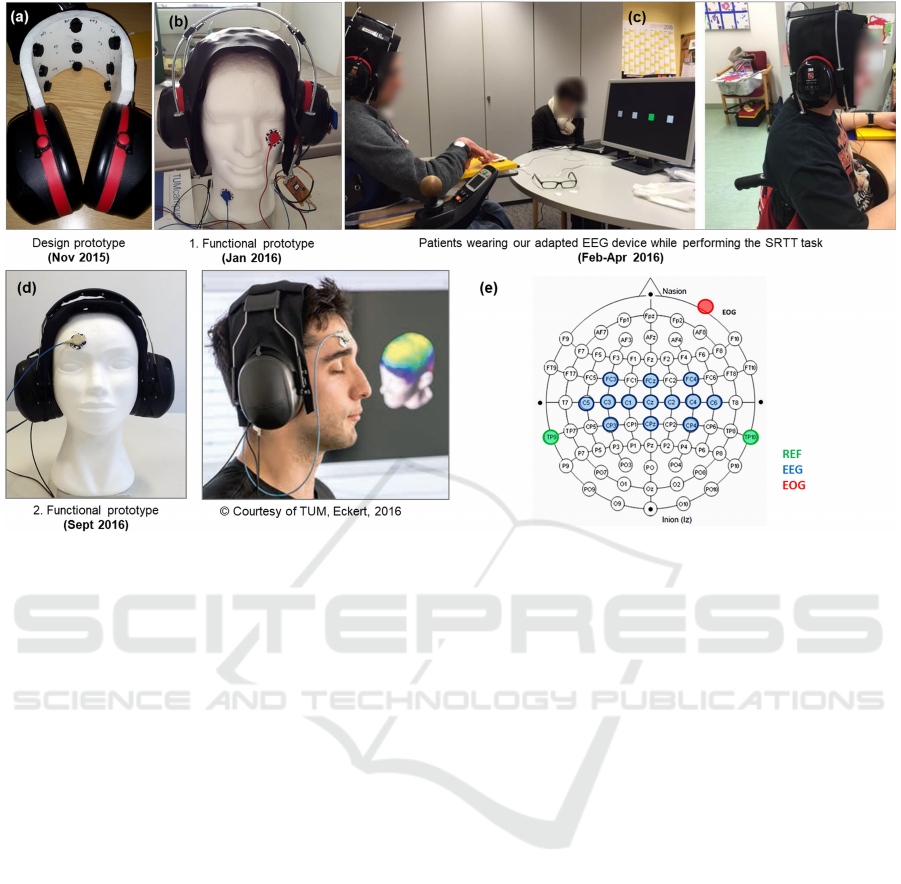

Figure 1: History of development of our adapted EEG device. 13 semi-dry EEG channels covering sensorimotor areas are

embedded into the elastic sheet between the earpieces. Note the optional electrooculogram (EOG) channel attached to the

cheek or forehead for capturing vertical or horizontal eye movements. (a) Design prototype; (b) 1. functional prototype used

in the studies described in this paper; (c) patients wearing our EEG device while performing the SRTT task in the first data

collection session; (d) 2. functional prototype, developed in follow-up work; (e) Electrodes positioning of our adapted EEG

device according to the international 10-20 system (Homan et al., 1987).

consumer systems for gaming and entertainment, and

(IV) open-source Do-it-Yourself (DIY) setups. A

fifth category is currently gaining increasing atten-

tion. These systems aim to close the gap between sci-

entific and consumer systems and focus on easy han-

dling, short preparation times, portability, and high

wearing comfort.

This paper aims at making a contribution in line

with this new category of EEG systems. In col-

laboration with the medical faculty we developed

an ease-of-use, unobtrusive EEG device to be em-

ployed in the study of sensorimotor disabilities in

patients with motor disorders. Envisaged in partic-

ular were adults and adolescents with a diagnosis

of CP, a medical condition characterized by motor

deficits caused by damage to the developing brain

pre-, peri- or post-natal. Event-related synchro-

nization/desynchronization (ERS/ERD) of the brain

mu- and beta rhythm constitutes a neuronal correlate

of motor action (Pfurtscheller and Da Silva, 1999).

ERS/ERD may constitute a useful measure in the

study of motor disorders of neuronal origin as well

on the evaluation of therapy efficacy. Measurement

of ERS/ERD was here measured during the execution

of a hand motor task adapted from the Serial Reaction

Time Task (SRTT) (Robertson, 2007).

2 CONCEPT, TECHNICAL

REALIZATION, AND

HANDLING

2.1 Requirements

As mentioned above the device here described was

developed having in view the investigation of sen-

sorimotor deficits in patients with CP. These present

impaired muscular imbalance and increased muscu-

lar tonus that results from neuronal damage during

brain development (Rosenbaum et al., 2007). Deficits

are not progressive but persist throughout the pa-

tients’ life. The degree of impairment varies depend-

ing on the brain areas affected and motor limitations

are often accompanied by learning difficulties, atten-

tion problems, perceptual impairments, speaking dif-

ficulties and/or epilepsy. The multi-symptomatology

in CP makes it a challenging condition to research

and demands a multidisciplinary approach when in-

vestigating possible rehabilitation strategies. From

the lifelong medical follow up of patients it becomes

clear that, whilst primary medical care provides vi-

tal treatment, patients need for inclusion is likely to

benefit strongly also from the collaboration between

medical expertise, neuroscience and advances in neu-

rotechnology.

Technical adaptations were performed in a commer-

cially available EEG system to conform to the follow-

ing requirements:

• unobtrusive visual appearance that is not imme-

diately associated with a clinical examination de-

vice.

• short preparation time: < 5 minutes.

• comfortable wearing for up to 30 minutes.

• easily adapted to different head sizes (from chil-

dren to adults).

• electrodes positioning according to the 10-20 sys-

tem (Homan et al., 1987) and covering the major-

ity of sensorimotor areas.

• resistance to hygienic treatment.

• positive reception/good acceptance of the device

by the participants.

2.2 Design Concept and Realization

Standard EEG recording equipment for scientific and

medical purposes usually consist of a cap of flexi-

ble fabric with electrode placeholders, an amplifier

connected to the electrodes via cables, and a com-

puter connected to the amplifier recording and stor-

ing the data (e.g. BrainProducts actiChamp). The cap

setup allows for flexible and precise positioning of the

electrodes and is comfortable to wear. However, de-

spite the high data precision achieved with these sys-

tems, some technical aspects make them non-optimal

for recordings in some clinical populations. Most

such systems use gel-based electrodes which require

long setup times, exceeding the patient’s endurance,

and are as such not usable. Alternative systems use

dry electrodes (e.g. Guger Technologies g.Nautilus)

which significantly reduce preparation time. How-

ever, dry electrodes require firm contact pressure of

the electrode on the scalp to yield good conductiv-

ity and as such significantly reduce wearing com-

fort. Moreover, dry electrodes are more susceptible to

noise and measurement artifacts than gel-based elec-

trodes. At last, the chin strap for closing and tight-

ening the cap can cause feelings of suffocation and

might not be tolerated by some patients. Also, the

chin-strap makes signal acquisition prone to artifacts

resulting from head and face movements as well as

talking. Patients with CP, especially adolescents, are

unlikely to sit still for long time. Some systems do not

make use of a cap setup, but rather a frame or flexi-

ble headband design, such as the Quasar HMS, or the

emotiv EPOC. These systems however were also in-

adequate for the envisaged group, partially because of

their obtrusive appearance, partially because of lim-

ited flexibility for electrode positioning. None of the

commercially available systems fullfilled all require-

ments which motivated the need for a costumized de-

sign.

As a compromise between flexible cap and stiff

frame setup which does not require a chin strap we

decided for a design mimicking headphones (see Fig-

ure 1). Headphones have natural unobtrusive appear-

ance as people are familiar with using them for mu-

sic listening. Furthermore, headphones apply contact

pressure around the ears which has proven comfort-

able to wear and allow for tight sit. In addition, the

headphones allow the recording electrodes to be em-

bedded within their headband and consequently to be

naturally positioned over motor areas, necessary to as-

sess sensorimotor-related brain activity.

As for sensors and electronics we decided to re-

use a worn-off emotiv EPOC device. Despite the orig-

inal purpose of the emotiv EPOC for gaming and en-

tertainment, there have been numerous scientific pa-

pers making use of the system. The system has sys-

tematically been validated with regard to the use for

scientific purposes, e.g. in (Hairston et al., 2014) and

(Debener et al., 2012). This shows that despite lower

signal quality, the system delivers usable data in a

wide spectrum of applications. The emotiv EPOC

sensor technology makes use of a semi-dry solution,

namely felt pads soaked with saline solution estab-

lishing conductivity between the proband’s scalp and

the gold-coated electrodes. The electrodes require a

certain contact pressure but the soft felt pads allow

for comfortable wearing. The emotiv EPOC headset

is a one-size for all frame with a fixed positioning of

the electrodes. Its original layout has mainly channels

over the pre-frontal areas.

We freed sensors and electronics from the original

plastic frame and included the raw modules into our

headphones setup. A flexible two-layer sheet made of

washable fabric was mounted in between the left and

right earpiece, which are held together by two curved

threaded metal bars. The two-layer sheet embeds and

hides 13 (of original 14) EEG electrodes and the con-

necting cables to the electronics. One channel was

spared for capturing vertical eye-movement via elec-

trooculogram (EOG) signals (see Figure 1). This al-

lows for either online or post-hoc eye-movement ar-

tifact reduction. The right earpiece was used as the

housing for electronics, leaving enough space to fill

it with rubber foam for sustaining sound insulation

and ensuring no contact of the proband’s ear with the

electronics. The electronics communicates wirelessly

with a transceiver connected via USB to a recording

computer. The original reference channels were re-

placed by longer cables connectable to the proband’s

left and right mastoids via electrocardiogram (ECG)

patches. Miscellaneous parts to assemble the whole

system were 3D-printed.

The emotiv EPOC hardware is compatible with

open source recording software, such as the Open-

Vibe framework (Renard et al., 2010). This allows for

convenient access to raw signals and high flexibility

in experiment design and implementation. Proband

preparation takes < 5 min.; after initial preparation,

electrode impedances stay stable for at least 30 min.

A simple mechanism allows for quick (< 5 min.)

adaptation of the headset to different headsizes (˜52-

58 cm diameter). For hygienic reasons, felt pads can

be replaced and the electrode sheet as well as the ear-

pieces be sanitized. More technical details are listed

in Table 1.

3 EVALUATION AND RESULTS

3.1 Data Quality Evaluation in SRTT

Task Protocol

For signal quality evaluation, data was collected from

one healthy subject performing the SRTT task in two

separate sessions. In the experiment, the participant

was presented 1 out of 4 possible targets on a com-

puter screen and had to respond with a corresponding

right hand key press. In total 40 trials were collected

per data set with an inter-trial pause of 10 seconds.

Each trial consisted of the visual cue presentation and

the subsequent participant response. The first session

was recorded using a Brain Products actiChamp 32-

channel gel-based active electrodes setup with 500 Hz

sampling rate. All leads were referenced to the aver-

age of left and right mastoid and impedances were

kept below 5kΩ. The second session took place on

a different day and was recorded using our adapted

EEG device with 128 Hz sampling rate. Also here,

all leads were referenced to the average of the left

and right mastoid; electrode connectivity was tested

using the Emotiv TestBench Software. Sensors were

adjusted until connectivity reached the ’green’ level

(corresponds to an impedance of <220kΩ according

to a test performed by Badcock et al. (Badcock et al.,

2015)).

1

https://emotiv.com/store/compare/

Table 1: Facts and figures. Some figures (*) were taken

from the emotiv EPOC specification

1

.

Sensors and channels

Number of channels 18 (13 EEG, 1 EOG, 2

Reference + 2 axis gy-

rometer)

Sensor technology* Semi-dry saline soaked

felt pads

EEG channel labels

(10-20 system)

FCz, Cz, CPz, FC3,

C1, C3, C5, CP3, CP5,

C2, C4, C6, CP4, EOG,

REF1, REF2

Electronics and signal acquisition

Sampling rate* 2048 Hz internal, fil-

tered and downsampled

to 128 Hz

Frequency response* 0.16 - 43 Hz

Resolution* 14 bit per channel (0.51

µV )

Wireless data trans-

mission*

emotiv proprietary

2.4GHz wireless (cus-

tom USB receiver)

Usability

Internal battery

power*

Li-poly battery, 680

mAh, > 12 hours

Maximum distance to

wireless transceiver

up to 10 meters, 1 meter

recommended to avoid

data packet loss

Stability of electrode

conductivity

tested up to 30 minutes

without re-applying

saline solution

Proband preparation

time

approx. 5 minutes

Applicability with re-

spect to head size

approx. 52-58cm diam-

eter

Adjustment to differ-

ent head sizes

< 5 minutes

Price per device in total approx. US$799

(emotiv EPOC US$ 699

+ <US$100 miscella-

neous)

Costs for spare parts

per data recording /

proband

approx. US$1 (3 single

use ECG patches, 13 felt

pads)

All data processing was carried out in MATLAB,

in part using functions provided by the EEGLAB tool-

box (Delorme and Makeig, 2004). First, the data from

the actiChamp device was downsampled to 128 Hz

to make it comparable to the data collected with the

adapted device. Then, each dataset was high-pass fil-

tered using a zero phase Hamming Windowed sinc

finite impulse response (FIR) filter with cutoff fre-

quency of 0.5 Hz. The data was then segmented into

epochs, time-locked to the moment of key-press. No

epochs were rejected for further analyses. For com-

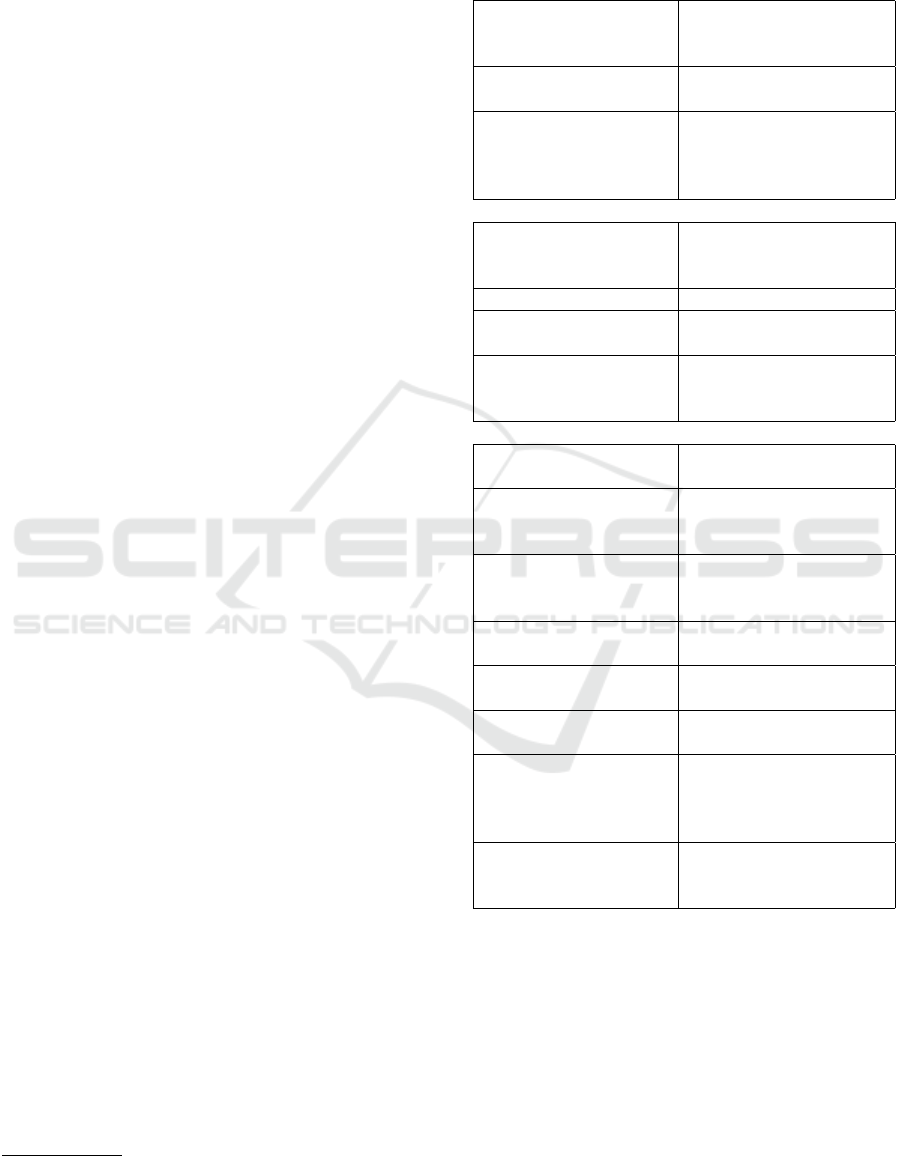

Figure 2: Panels (a): Depiction of bandpass-filtered (8-13 Hz) signal recorded at position C3 for trial 10, for both datasets

(actiChamp in upper panel, adapted device in lower panel). Panels (b): Power spectrum of channel C3 separately computed

on 2 seconds before and 2 seconds after the key-press. Thick lines represent the average power spectra across trials (n=40);

shaded backgrounds represent the single standard deviation across trials. Panel (c): Comparison of average power spectra of

both devices.

parisons we focused on channel C3, located approxi-

mately over the right-hand related contralateral mo-

tor cortex, and which therefore we expect to show

a strong sensorimotor effect (mu-power suppression,

see (Pfurtscheller and Da Silva, 1999)). Figure 2 (a)

shows the mu-bandpass-filtered signals (zero phase

Hamming Windowed sinc FIR filter with cutoff fre-

quencies 8-13 Hz) of channel C3 exemplarily from

one single trial. In both datasets suppression of mu-

power around the time of key-press can be observed.

In panel (b) the power spectra of channel C3 are de-

picted, both for the period of 2 seconds before and

2 seconds after the key-press. The spectra show that

power suppression is mainly concentrated on the mu-

band. The amount of suppression is quantitatively

similar in both datasets. Also, the standard deviation

of trial-to-trial power spectra does not differ signif-

icantly across the two devices. Panel (c) shows the

comparison of average power spectra of both devices.

We observe approximate 5dB difference between the

power spectrum of the actiChamp and the adapted de-

vice which is relatively uniform across the relevant

spectrum (0-40Hz). We interpret this as added white

noise in the adapted device due to lower electrode

conductivity.

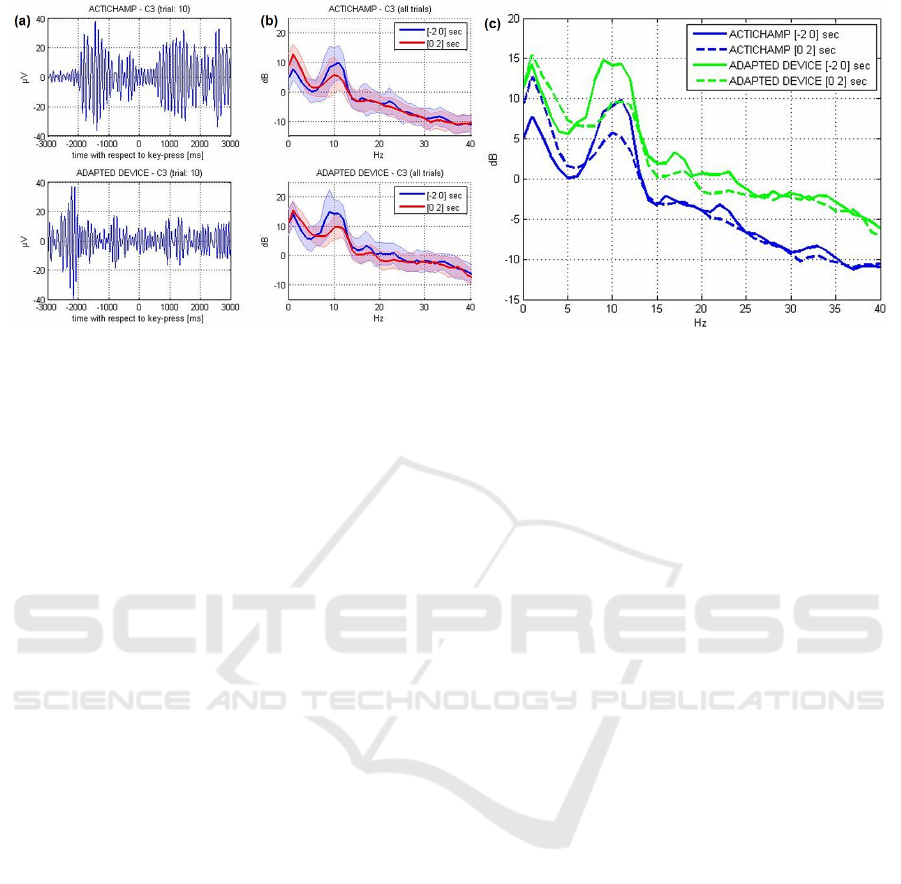

ERD/ERS was computed from the mu-bandpass

and beta-bandpass filtered signals according to

Pfurtscheller’s method (Pfurtscheller and Da Silva,

1999). The upper panels of Figure 3 show the aver-

age ERD/ERS time-courses of channel C3 compar-

ing both recording sessions. Furthermore, we per-

formed a time-frequency analysis of channel C3 us-

ing the wavelet-based event-related spectral perturba-

tion (ERSP) technique (Makeig et al., 2004), see Fig-

ure 3, middle panels. The lower panel of Figure 3

shows that the power modulations in the respective

time-frequency bins are statistically significant across

trials (p<0.05, FDR-corrected). For ERSP computa-

tion we used the epoch [-3 3] seconds with respect

to key press. Wavelet parametrization was set to 3 cy-

cles for the lowest frequency (2 Hz) expanding gradu-

ally towards half of the number of cycles for the high-

est frequency (30 Hz). As a result, we observe clear

mu-power suppression and traces of beta-power sup-

pression in both datasets. There are two main differ-

ences between the two datasets: (1) Motor prepara-

tion related ERD onset with respect to the movement

onset appeared earlier in the first dataset compared

to the second data set. (2) The recovery time (ERS

after motor execution) is longer in the second data

set (around 1500 ms) compared to the first data set

(around 1000 ms). Whether or not these variations re-

sult from the different measurement setups or rather

the daily constitution of the subject cannot be stated

with certainty. In any case, the reduction in mu power

derived from signals collected over motor areas that

is expected to occur during preparation of movement

is visible in both data sets. This observation, together

with the practical advantages of the new EEG system

described above, validates and supports the use of the

new adapted EEG system to assess changes in mu-

power ERD/ERS over motor areas.

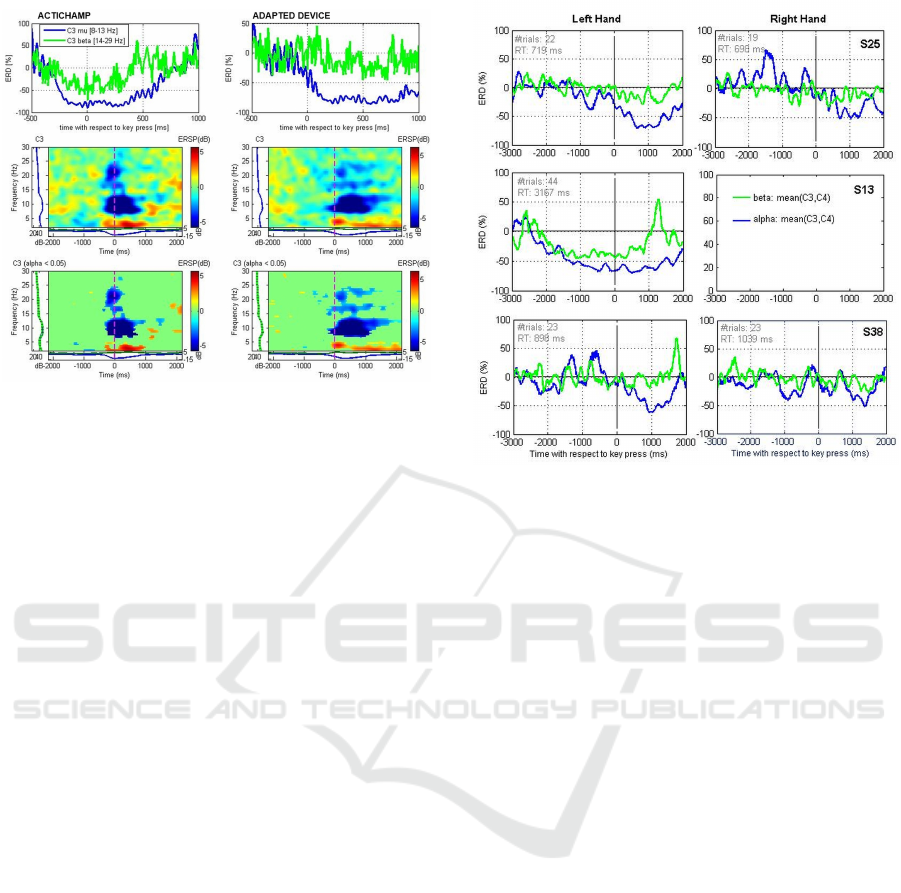

3.2 Analysis of Patient Data

The same adapted SRTT task was employed to assess,

with the adapted device, hand motor-related ERD in

adolescents and adults with and without a diagnosis

of CP. Example ERD measures are illustrated in Fig-

ure 4 for three participants: S25 (upper panel, 13

Figure 3: Upper panels: Analysis of mu- and beta-power

event-related desynchronization (ERD) in channel C3 ac-

cording to [2]. Middle panels: Time-frequency represen-

tation of channel C3 time-locked to the participant’s key

press using the wavelet-based event-related spectral pertur-

bation (ERSP) technique. Lower panels: show only those

time-frequency bins which were found statistically signifi-

cant across trials (p<0.05, FDR-corrected).

years old, healthy, best hand: right), S13 (middle

panel, 45 years, CP with hemiparesis, best hand: left),

S38 (lower panel, 15 years old, ataxic CP, best hand:

right). Measurements were performed in a normal of-

fice at the day rehabilitation centers attended by the

patients (participant S25, though not attending any re-

habilitation center, was also tested in the same center).

ERD is illustrated for both left and right hands, ex-

cept for participant S13. This patient has a hemipare-

sis that prevents any movement of the right arm/hand,

and therefore he performed the SRTT task with the

left hand only. The ERD measures shown were av-

eraged from mu- and beta- bandpass filtered signals

recorded from channels C3 and C4. Reductions in

mu-power (blue lines) are visible for all cases except

for participant S38 with the right hand. Even though

signal preprocessing included the removal of epochs

containing artifacts (by automatic and visual assess-

ment), these may still have affected the quality of

the data and decreased the amount of mu-suppression

computed. Participant S38 (middle panel) shows a

strong ERD effect, especially for the mu-rhythm. The

fact that the reaction time recorded for this participant

was much longer than for the other participants (aver-

age Reaction Time (RT) of 3167-ms in comparison to

719-ms and 898-ms for participants S25 and S38 re-

spectively) may have facilitated the development of a

visible change in mu power with time. It should also

be noted that this participant is an adult and that, un-

like adolescent participants, was able to remain quiet

Figure 4: Hand motor-related ERD in three adolescents and

adults with and without a diagnosis of CP.

during the recording. This was observed to be impor-

tant to increase the number of artifact-free epochs and

the probability of capturing a motor-associated sup-

pression of mu power.

3.3 Patient and Experimenter Feedback

The healthy participant tested for the system evalu-

ation described the system as comfortable and not

heavy. This initial feedback has been confirmed by

the patients and participants of the main experimen-

tal study. A short questionnaire has been delivered

to some of the participants after the EEG recordings

to collect the first impressions on the device. Most

patients reported the device to be comfortable (5 out

of 5 persons), not heavy (3 out of 5) and not looking

harmful or dangerous (5 out of 5). None felt bothered

by the system but some were nevertheless aware of it

during the recordings (2 out of 5). Researchers on the

other hand were very pleased with the easy way the

system can be set up and with the short preparation

time required, an aspect that they found very help-

ful when testing all the patients, not only the younger

ones.

4 CONCLUSION

Research studies with children, adolescents, with per-

sons having a reduced attention span or with patients

receiving medical treatment for long periods of time,

demand a careful planning of the experimental tests.

Short experimental testing time, test equipment with

non-clinical appearance and/or that does not cause

discomfort are relevant factors that influence adher-

ence to participate and can also affect the quality of

the data collected. An ease-of-use, unobtrusive EEG

device is described in this paper having in view the

investigation of motor-related sensorimotor rhythms

in patients with cerebral palsy. Commercially avail-

able EEG devices have clinical appearance and re-

quire long preparation times. Our proposed EEG de-

vice addresses these issues. Experimenters reported

smooth data collection and overall acceptance of the

system among patients. The changes in ERD over

time during an adapted SRTT task meet the observa-

tions described in the literature (e.g. (Pfurtscheller

and Da Silva, 1999)) this way supporting the func-

tionality of our adapted EEG device for the assess-

ment of sensorimotor-related measures of brain activ-

ity in patients (adults and adolescents) with sensori-

motor disorders of neuronal origin.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to thank Claas Br

¨

uß for his con-

tributions and support during the development of the

system.

REFERENCES

Badcock, N. A., Preece, K. A., de Wit, B., Glenn, K.,

Fieder, N., Thie, J., and McArthur, G. (2015). Valida-

tion of the emotiv epoc eeg system for research quality

auditory event-related potentials in children. PeerJ,

3:e907.

Debener, S., Minow, F., Emkes, R., Gandras, K., and Vos,

M. (2012). How about taking a low-cost, small,

and wireless EEG for a walk? Psychophysiology,

49(11):1617–1621.

Delorme, A. and Makeig, S. (2004). EEGLAB: an open

source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dy-

namics including independent component analysis.

Journal of neuroscience methods, 134(1):9–21.

Hairston, W. D., Whitaker, K. W., Ries, A. J., Vettel,

J. M., Bradford, J. C., Kerick, S. E., and McDow-

ell, K. (2014). Usability of four commercially-

oriented EEG systems. Journal of neural engineering,

11(4):046018.

Homan, R. W., Herman, J., and Purdy, P. (1987). Cere-

bral location of international 10–20 system electrode

placement. Electroencephalography and clinical neu-

rophysiology, 66(4):376–382.

Makeig, S., Debener, S., Onton, J., and Delorme, A. (2004).

Mining event-related brain dynamics. Trends in cog-

nitive sciences, 8(5):204–210.

Pfurtscheller, G. and Da Silva, F. L. (1999). Event-

related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchro-

nization: basic principles. Clinical neurophysiology,

110(11):1842–1857.

Renard, Y., Lotte, F., Gibert, G., Congedo, M., Maby, E.,

Delannoy, V., Bertrand, O., and L

´

ecuyer, A. (2010).

OpenViBE: an open-source software platform to de-

sign, test, and use brain-computer interfaces in real

and virtual environments. Presence: teleoperators

and virtual environments, 19(1):35–53.

Robertson, E. M. (2007). The serial reaction time task: im-

plicit motor skill learning? The Journal of Neuro-

science, 27(38):10073–10075.

Rosenbaum, P., Paneth, N., Leviton, A., Goldstein, M., Bax,

M., Damiano, D., Dan, B., Jacobsson, B., et al. (2007).

A report: the definition and classification of cere-

bral palsy april 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl,

109(suppl 109):8–14.

Vuckovic, A., Pineda, J. A., LaMarca, K., Gupta, D., and

Guger, C. (2015). Interaction of BCI with the underly-

ing neurological conditions in patients: pros and cons.

Interaction of BCI with the underlying neurological

conditions in patients: pros and cons, page 5.