Common Information Sharing on Maritime Domain

A Qualitative Study on European Maritime Authorities’ Cooperation

Ilkka Tikanmäki

Research, Development and Innovations, Laurea University of Applied Scienses, Vanha maantie 9, Espoo, Finland

Keywords: Information Sharing, Authorities’ Interaction, Cooperation, Maritime Surveillance, Maritime Safety,

Common Information Sharing Environment.

Abstract: The most important element of the Common Information Sharing Environment (CISE) is to allow the data

collected by the maritime authority to be available for specific purposes by the other maritime authorities.

Different actors collect data on a number of occasions and CISE allows for cross-border and cross-sector

information exchange. Compliance with the European Maritime Security Strategy and CISE model maximises

interoperability with other already existing and functioning Maritime Safety Authorities’ (MSA) entities. This

qualitative study brings out European Union projects FiNCISE, EUCISE and MARISA together with

authorities’ cooperation in maritime domain. A response to security challenges and improving safety requires

the cooperation of all administrative sectors, other actors, and close interaction. The action of authorities needs

to be more strongly aimed at common goals. Authorities will contribute to a stronger position to act together

culture and a strong commitment to common goals. The challenges are not solvable by a single administrative

sector or a single actor alone posed by the complex global environment. Cooperation insist deep and

committed cooperation between the authorities and other actors.

1 INTRODUCTION

EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy (IMP) focus on

issues that are common for cross-sector and/or cross-

border. These crosscutting policies are; Blue Growth,

marine data and knowledge, maritime spatial

planning, integrated maritime surveillance, and sea

basin strategies. IMP is a framework with objectives

to maximise the sustainable use of seas and oceans

with intention to increase maritime and coastal

region’s growth, to build a knowledge and innovation

base for maritime policy, to improve quality of life in

coastal areas, to promote EU leadership in

international maritime affairs, to raise a visibility of

European maritime, and to create international

coordinating structures for maritime affairs and to

define responsibilities and competencies of coastal

areas (European Commission, 2017).

On 2005 the European Commission forwarded a

Communication on an Integrated Maritime Policy for

setting planned objectives for a Green Paper. On 2006

a Green Paper “A Future Maritime Policy for the

Union: a European Vision of the Oceans and Seas”

was published (Commission of the European

Communities, 2006). Commission of the European

Communities communication COM(2007) 575 was a

proposal for IMP: “An integrated Maritime Policy for

the European Union”. This communication is known

as the Blue Paper and it gives outlines for an

Integration of Maritime Surveillance for enhanced

and coherent sharing of information. The European

Commission published on 2010 a Communication “A

Draft Roadmap towards establishing the Common

Information Sharing Environment for the

surveillance of the EU maritime domain” (European

Commission, 2010a). The objective of the IMP is to

“foster coordinated and coherent decision-making to

maximise the sustainable development, economic

growth and social cohesion of the Member States, in

particular with regard to coastal, insular and

outermost regions in the Union, as well as maritime

sectors, through coherent maritime-related policies

and relevant international cooperation” (European

Parlament, 2011).

The study concentrates on European Maritime

Authorities' cooperation on surveillance and

information sharing cross-border and cross-sector.

Due to the fact that numerous systems are not yet

interconnected and operate simultaneously, the

authorities shall contribute to a stronger position to

TikanmÃd’ki I.

Common Information Sharing on Maritime Domain - A Qualitative Study on European Maritime Authoritiesâ

˘

A

´

Z Cooperation.

DOI: 10.5220/0006582502830290

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (KMIS 2017), pages 283-290

ISBN: 978-989-758-273-8

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

act together culture and a strong commitment to

common goals. The research question of this study is:

How to respond to security challenges and improve

cooperation and interaction between different

administrative sectors?

1.1 Structure of This Paper

The second chapter of this study concerns

methodology used, the third chapter presents the

factors affecting the European Union's maritime

policy, and is divided into sections; CISE program,

EUCISE-, FiNCISE- and MARISA projects and

maritime security-related cooperation FIMAC

organization. The fourth chapter discusses the

findings of the study, and finally the fifth chapter

includes a discussion and conclusions of the study.

2 METHODOLOGY

The research is qualitative in nature, and the purpose

of the study is to find the entities to examine and to

understand their meanings. The study is a qualitative

study of the characteristic description of the real life

(Hirsjärvi, Remes & Sajavaara, 2007). An inductive

content analysis of results indicates the

generalizations and conclusions drawn from the facts

that emerge from the source material to show

consistency (Alasuutari, 1995). Earlier knowledge

and practical experiences raise the researcher's

preconceptions and the assumed starting points for

concept formation, although the researcher is ready to

overcome it.

Dubé and Pare (2003) claim that “Case study

research offers the opportunity to use many different

sources of evidence”. There are weaknesses and

strengths in all case study sources and therefore, it is

advisable to use several sources of evidence in a case

study. The main asset of the case study is the ability

to make different kinds of evidence sources to get

more information about issues than any single

method. (Yin, 2009.) The research material was

acquired by participatory observing, scientific

reports, collected articles, and literary review. The

main sources of the research are the regulations of the

EU's Integrated Maritime Policy, public material

relating to EU projects, a public material of the

Border Guard and theme related Valtonen’s and

Vuorisalo’s dissertations. Participating and observing

project meetings, workshops and discussions with

other participants were beneficial source material.

Observation in data collection method is used in

conjunction with another method because it is

challenging to analyse the material obtained solely

from observation. Observation is a method for

verification of conflicts between the experimental

data and the reality. (Tuomi & Sarajärvi, 2004;

Järvinen & Järvinen, 2004). The observation as a

method allows for the creation of an immediate

relationship in the natural conditions to the

observable objects. However, the presence of the

observer may have an impact on the results, as

observation may cause suspicion, resistance and

abnormal behaviour among the group to be

investigated. (Saaranen-Kauppinen & Puusniekka,

2009). The study was done as a qualitative study

where the results are based on the researcher’s

inference ( Huttunen & Metteri, 2008).

3 COMMON INFORMATION

SHARING IN MARITIME

DOMAIN

The main guiding factor for the Common Information

Sharing Environment (CISE) mechanism is to permit

that information collected for the specific purpose by

a maritime authority is available to other maritime

authorities. Information is collected multiple times by

different actors and CISE allows cross-border and

cross-sector information exchanges. (European

Commission, 2014a).

3.1 CISE

Currently, there are seven maritime surveillance user

communities, referred also as sectors: maritime

safety, General Law enforcement, border control,

customs, fisheries control, marine environment, and

defence. EU-wide information exchange

environment allows automatic and seamless

information exchange among over 300 public

maritime authorities at EU and national level

(European Commission, 2010a). CISE Technology

Advisory Group’s (TAG) gap analysis in 2012

showed that only 30% of the collected and relevant

data to other authorities is shared (European

Commission, 2014b). However, aforementioned does

not mean that there should be one common maritime

picture, but that the authorities should have the

opportunity to form the desired maritime picture for

their purposes.

Test Project on cooperation in executing various

maritime functionalities at sub-regional or sea-basin

level in the field of integrated maritime surveillance

(CoopP) was a test project that investigated needs,

barriers, benefits and technologies for information

exchange. The CoopP project’s aim was to enhance

the development of CISE. CoopP had 31 partners

from ten Member States, seven EU agencies and

international organisations and approximately 40

maritime authorities involved in the project. CoopP

project described three High- Level Use Cases 1)

Baseline operations, 2) Targeted operations, and 3)

Response operations. The baseline operations’

purpose was to ensure the lawful, safe and secure

performance of maritime activities. The aim of the

targeted operations was to react to specific threats to

sectoral responsibilities and to give support to

operational decision making. The response

operations’ intent was to respond to events affecting

several actors, cross-sector and cross-border. During

the project was analysed nine Use Cases. Criteria for

selected Use Cases was to ensure that selected cases

cover all user communities. (Finnish Border Guard,

2014.)

Policy-oriented marine Environmental Research

in the Southern European Seas (PERSEUS) was a

four-year (2012 - 2015) European Union’s Seventh

Framework Programme (FP7) for research,

technological development and demonstration. The

project’s aims were to develop and test European

maritime surveillance system by integrating existing

national and European level systems, and by

upgrading and improving them and thereby

supporting the creation of CISE. The PERSEUS

Demonstration Project was implemented through live

exercises in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy and Greece.

Exercises showed that legacy systems can

interoperate and the authorities of the Member States

can cooperate seamlessly. (PERSEUS, 2015.)

3.2 EUCISE

A European test-bed for the Maritime Common

Information Sharing Environment in the 2020

perspective (EUCISE 2020) project’s general

objective is to develop European maritime safety by

building a common information sharing environment

for the maritime surveillance. The project is

coordinated by Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI) with

40 partners from the European Union and European

Economic Area (EEA). EUCISE 2020 combines

existing control systems and networks and provides

the authorities the necessary information on maritime

surveillance. The objective is to allocate maritime

information to all maritime sectors of the EU and the

EEA in the future. EUCISE 2020 is based on

voluntary cooperation between the authorities

involved in the European maritime surveillance.

EUCISE 2020 is based on existing information

exchange systems and does not replace them. The aim

of the EUCISE project is to share the collected

information with other maritime operators to the

extent that several authorities collect and process the

same information. (EUCISE, 2015a.)

Maritime tracking data, which will be shared

within EUCISE 2020 project partners, include

information such as vessel locations, routes, freight,

maps, and weather and sea conditions. (EUCISE,

2015b.) The pilot project CoopP defined nine

significant use cases. These use cases are used in the

EUCISE 2020 project as they present several sectors

of maritime authorities.

3.3 FIMAC

Finnish Maritime Authorities Cooperation (FIMAC)

has its roots back in 1994 when the ministerial

committee for administration development published

a report on the rationalization of maritime functions.

Cooperation parties are; Finnish Transport Agency,

Finnish Transport Safety Agency, Finnish Border

Guard and Finnish Navy. FIMAC’s strategic goals

are; increasing maritime safety, development of data

management and information exchange, international

influence, and joint use of capacity (FIMAC, 2014).

Co-operation promotes risk management and

provides a common sense of awareness for maritime

safety, which makes efficient and flexible use of

public resources. The actors jointly utilize their

experts, information obtained and research data from

sea areas. The common information exchange

environment is developed according to user needs. In

international relations, FIMAC works actively and

systematically to achieve common national goals.

National co-operation will ensure effectiveness in

issues important to Finland. Infrastructure, resources,

expertise, and procurement coordination are

increasingly utilized to improve efficiency and to

minimize total costs. Since the cooperation

foundation, authorities have saved funds over 50

million euros by investments on data transmission

networks, sensors, and radio networks (FIMAC,

2014).

Cooperation today is routine co-operation, which

automatically searches for common solutions that

benefit both society and maritime safety. Finland has

always had a desire for cooperation between the

authorities (Luokkala, 2009). The need for

cooperation between the authorities in Finland is due

the limited resources of the public authorities and the

convergence of the authorities’ organizations,

especially on knowledge management (Tuohimaa,

Tikanmäki & Rajamäki, 2011). Even though the tasks

of the authorities are different, there is congruence in

the various tasks required the necessary awareness. In

addition, the tasks and resources of gathering

information can be shared cost-effectively between

the various public authorities.

3.4 FINCISE and National CISEs

Finnish National Common Information Sharing

Environment for Maritime Surveillance (FiNCISE) is

a European Union’s European Maritime and Fisheries

Fund (EMFF) programme. Duration of the project is

two years from November 2015 to November 2017.

The project consortium consists of Finnish Maritime

Authorities Cooperation (FIMAC) that has as

partners; Border Guard, Navy, Traffic Safety Agency

and Traffic Agency. FiNCISE has also as a partner

Finnish Environment Institute to test external services

with other authorities. (FiNCISE, 2015.)

The aim of the FiNCISE project is to support the

cooperation in the framework of FIMAC to create a

maritime situational picture and distribute it to the

cooperative parties to support their activities. Another

goal of the project is to promote the well-functioning

FIMAC operations model in national and

international projects and forums and thus to improve

maritime safety in the Baltic Sea. The technical

objective of the FiNCISE project is to improve the

interoperability of national maritime surveillance

systems across sectors and across borders within the

European Union. (FiNCISE, 2017.)

The focus is system-to-system information

exchange. Specific objectives for FiNCISE project

are to develop a national enterprise architecture

description related production and to share National

Maritime Surveillance Picture (NMSP), Maritime

resource situation picture (MRSP), and other

Maritime Situation Awareness (MSA) information.

FiNCISE expects following operational benefits:

More cost-efficient maritime surveillance and

maritime operations;

Improved data quality, description, system-to-

system sharing architecture, and enhanced

interoperability;

Added value services and advanced

understanding of the maritime situation in

various sectors. (Laaksonen, 2017.)

FiNCISE will implement following technical

solutions: 1) describe an enterprise architecture with

processes, 2) define requirements for a national

solution, 3) define a service channel to connect

databases, 4) produce a description of the concept of

interface solutions to system-to-system sharing, 5)

connects at least one concrete pilot-case from the

legal system to another, both nationally and EUCISE

interface, and, 6) study possibilities to use open

source technology. (Laaksonen, 2017.)

In addition to FiNCISE, there are interoperability

projects ongoing in other member states funded by

European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) and

managed by the European Commission’s European

Agency for Small and Medium Enterprises

(EASME). In Spain, Finland, Greece, Portugal,

Romania, Bulgaria and Cyprus, a total of 10 ongoing

projects are going on in the period from January 2016

to December 2018. The objective of these projects is

to “foster the information exchange across sectors and

borders by supporting the improvement of IT

interoperability between national authorities’

systems” (JRC, 2017).

3.5 MARISA

Maritime Integrated Surveillance Awareness

(MARISA) project aims to provide a more

informative and synthetic information on the design,

development, improvement and testing of new

functionalities, services and co-operation, and to

improve the validity of available information for

decision-making. Data fusions utilize information

from a variety of sources of information, such as

radar, infrared, camera, satellite, AIS, positioning

system, social media, or observation system. In

addition to the numerous sources of information from

the authorities, social media is a mechanism for the

communication of citizens by the public, where

everyone has the ability to be an active observer and

messenger, as well as a content provider in addition

to receiving information. The objectives of the

MARISA project are to: create an improved situation

awareness, support maritime professionals

throughout the life cycle, facilitate cooperation

between adjacent and cross-border agencies and

promote the dynamic ecosystem of users and service

providers, and enable stakeholder enrichment of

situation awareness by integrating their own

knowledge by creating locally enriched status

knowledge and sharing centralized awareness.

(MARISA, 2017.)

Compliance with the European Maritime Security

Strategy and CISE model maximises interoperability

with other already existing and functioning MSA

entities. The MARISA toolkit is designed to

streamline integration with existing and future MSA

operating systems to enable different configurations

and recovery levels. This ensures full compatibility

with the CISE and European policies, facilitating the

interagency interoperability and cooperation, and

thereby allowing each Member State to decide when

and whether or not additional sources of information

are relevant to its operation. (MARISA, 2017.)

MARISA enables Design Science Research

Methodology (DSRM), user-centred methods for

designing and implementing information systems.

“MARISA therefore focuses on taking these benefits

to the next level, while remaining completely

integrated in the current European policy” as stated in

MARISA Grant Agreement. (MARISA, 2017.)

MARISA project will benefit previous EU

projects, such as CoopP and PERSEUS, operational

scenarios referred to as use cases and their

descriptions. Use cases and trials in MARISA project

will use five use cases (UC) that are based on CoopP

project. Use cases are: 1) UC 13b: Inquiry on a

specific suspicious vessel (cargo related), 2) UC 37:

Monitoring of all events at sea in order to create

conditions for decision making on interventions, 3)

UC 44: Request any information confirming the

identification, position and activity of a vessel of

interest, 4) UC 70: Suspect Fishing vessel/small boat

is cooperating with other type of vessels (m/v,

Container vessel etc.), and 5) UC 93: Detection and

behaviour monitoring of IUU (Illegal, Unreported

and Unregulated fishing) listed vessels. (MARISA,

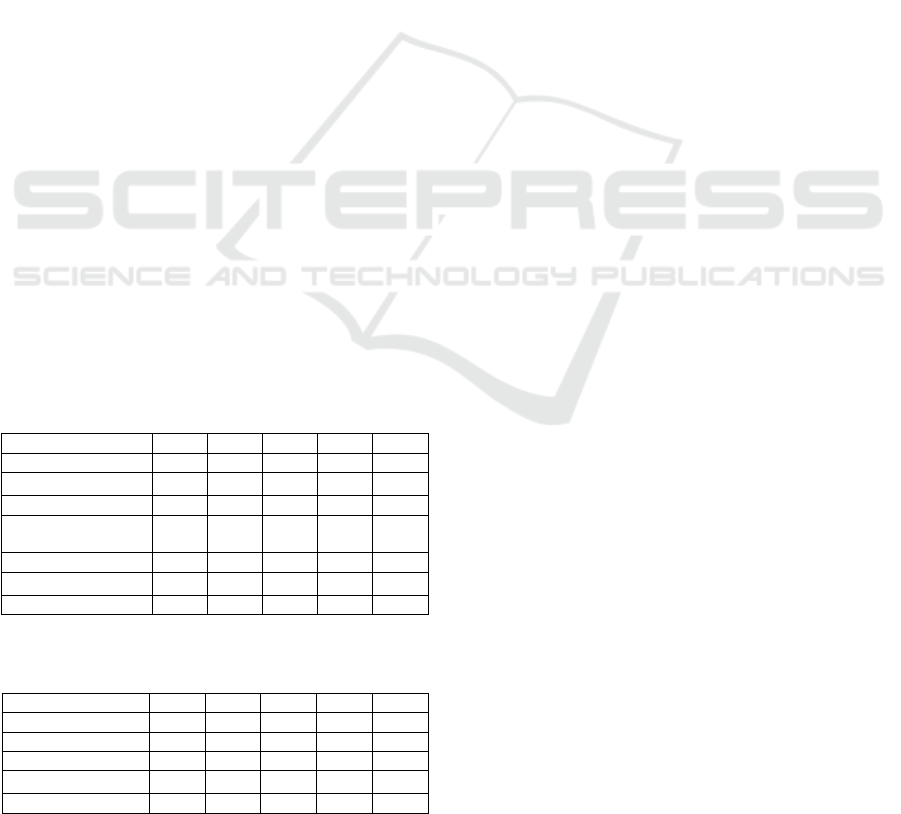

2017.) Table 1 presents potential User Communities

interested in Use Cases. Use cases will be exercised

in five different areas as Operational Trials. Table 2

clarifies premeditated Operational Trial areas and use

cases. These trials are exercised on North Sea, Iberian

Sea, Strait of Bonifacio, Ionian Sea, and the Aegean

Sea.

Table 1: User Communities and Use Cases (Adopted from

MARISA, 2017).

13b

37

44

70

93

Border Control

X

X

X

Customs

X

X

X

X

Defence

X

X

X

X

General Law

Enforcement

X

X

X

X

Marine Environment

X

X

X

X

Fisheries Control

X

X

X

X

Maritime Safety

X

X

X

Table 2: Operational Trials and Use Cases (Adopted from

MARISA, 2017).

13b

37

44

70

93

Northern Sea

X

X

X

X

X

Iberian Sea

X

X

Strait of Bonifacio

X

X

X

Ionian Sea

X

X

X

X

Aegean Sea

X

X

X

X

4 RESEARCH FINDINGS

Data from sensors of different authorities are

combined, thereby enabling the analysis of

information and, consequently, the most accurate

maritime picture. The information obtained in the

operating environment is necessary to form a

comprehensive maritime picture. Operation

environmental information needed is, such as

geographic information, oceanography research data

and weather conditions. The technique ensures the

use of common information only for the desired

organisations and the intended purpose. In connection

with the introduction of technical solutions, a

standardised approach will be implemented to ensure

the exchange of information. (Vuorisalo, 2012.)

According to Vuorisalo (2012) identification of

abnormal functions is hampered by:

decision-makers lack sufficient and

necessary information

problems arising from the

incompatibility of technical standards

between systems

lack of information due to the limited

number of sensors

customer orientation is attractive in

business and sustainable solutions

the excessive amount of information

The actors involved in the dissemination of

information should prepare for the harmonization of

information. By influencing political decision-

making, favorable conditions for sharing information

are created. Mutual benefit and interdependencies, as

well as networking and its benefits in information

sharing, must be understood. Such cooperation will

facilitate the introduction of new technologies in the

maritime community. (Vuorisalo, 2012.)

Interoperability plays an important role in

collaborative multi-agency and multinational action.

IEEE defines interoperability as “the ability of two or

more systems to exchange data and to mutually

understand the information which has been

exchanged” (IEEE, 1990). Interoperability can be

defined as the ability to communicate and share

information in public security organizations' systems

and it includes internetworking functionality

(European Commission, 2010b). Interoperability

requires co-operation, compatible systems, training

co-operation, and collaborative capability.

In order to ensure effective co-operation, all

stakeholders need to share visions, agree on

objectives and target priorities. Actions at a cross-

border level can be successful if all the Member

States concerned give adequate priorities and

resources to meet their own interoperability goals in

order to reach the agreed targets within the agreed

timetable. The European Union (EU) share

interoperability to four layers and political context as

outlined in the following paragraphs.

EU describes the political context as follows:

“The establishment of a new European public service

is the result of direct or indirect action at the political

level, i.e. new bilateral, multilateral or European

agreements”. However, political support and

assistance are needed when new services are not

directly linked to new legislation, such as CISE's

case, but they are created to provide better public

services. Moreover, political support is necessary for

cross-border interoperability efforts in order to

facilitate cooperation between public administrations.

(European Union, 2011.)

At the point of view of legal interoperability,

every public administration involved in the provision

of a European public service work within its own

national legislation. Sometimes incompatibility of

the laws of the various Member States makes it more

complicated or even impossible to cooperate. When

exchanging information for the provision of

European public services, the legal validity of data

must be maintained across borders and data

protection legislation must be respected. (European

Union, 2011; EUCISE, 2015c.)

The organisational interoperability aspect

addresses cooperation between organisations, such as

public administrations in different Member States, to

reach their commonly agreed goals. Organisational

interoperability signifies in practice the integrated

business processes and related data exchange, and

also tends to respond user community by making

services available, easily identifiable, easy to use, and

user-specific. (European Union, 2011; EUCISE,

2015c.)

Semantic interoperability enables organisations to

process data from external sources in an appropriate

manner and ensures that the precise meaning of the

information exchanged is understood and maintained

in the exchange between the parties. The various

linguistic, cultural, legal and administrative

circumstances of the Member States pose major

challenges. Multilingualism in the EU adds to the

complexity of the problem. (European Union, 2011;

EUCISE, 2015c.)

Technical interoperability covers the technical

aspects of the integration of information systems and

includes, such as user interface specifications,

interconnection services, data integration services,

data presentation and information exchange.

Although the public administration has its own

specific characteristics at a political, legal,

organisational and semantic level, interoperability at

the technical level is not particularly relevant to

public administration. Therefore, technical

interoperability must be ensured through official

requirements and standards. (European Union, 2011;

EUCISE, 2015c.)

The necessary confidence is built on a stable and

long-term cooperation. A broad cooperation network

can be used to develop and exploit of all partners

involved in the network. Multinational cooperation

develops technical and operational solutions that

enable the integration of systems in different

countries. The integrated security operating model

provides a cross-sectoral basis for managing large-

scale security threats. (Prime Minister’s Office,

2017.)

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Broad collaboration between partners improves the

Maritime Awareness and safety. Interagency

cooperation is essential for the various actors in order

to have sufficient knowledge of other concepts,

measures, resources and plans. Interagency

cooperation aims at a cost savings to increase

efficiency (Tikanmäki, Tuohimaa & Ruoslahti,

2012). Good cooperation is a prerequisite for proper

functioning (Taitto, 2007).

In the area of maritime surveillance, there is no

inherent complexity, which is due to the fact that

numerous systems are not yet interconnected and

operate simultaneously. It is therefore recommended

adopting common definitions for the different

categories and levels of information management in

the field of maritime surveillance.

Collaboration and cooperation are based on a trust

in all joint operations and actions (Rajamäki and

Knuuttila, 2015). Trust and knowledge sharing are

identified as a key part of cross-border cooperation

(Luis, Derrick, Langhals, and Nunamaker, 2013). At

operative-strategic level, safety and security co-

operation are based on effective cooperation between

authorities and effective cooperation solutions.

Participation in international cooperation and the

ability to manage the domestic security contexts will

support the effectiveness of cooperation. At a tactical

level, a security actor is primarily required for

professionalism and reliability. The most important

development target for security cooperation at all

levels is the ability to cooperate. Contributing factors

to the development of cooperation skills are

developing cooperation processes, measurement,

feedback system, and a common terminology

(Valtonen, 2010).

The Internal Security authorities take advantage

of new technologies and monitor actively its

development. A technological development opens the

means to curb the rise in costs. The authorities are

required to utilize modern resources and cost-

effective use. The actions of the authorities should in

future be stronger than before, as well as common

goals aimed for new approaches rely on pioneering.

The authorities must be able to anticipate better the

changes in the operating environment; operational

authorities are required to act as an example in

developing their own services. The aim is to develop

a user-driven, together with productivity and

profitability, increasing digital public services and

policies. The government requires in its report a

modern and cost-effective use of resources from

internal security authorities. (Ministry of the Interior,

2016).

A response to security challenges and improving

safety requires the cooperation of all administrative

sectors, other actors, and close interaction. The action

of authorities needs to be more strongly aimed at

common goals. Authorities will contribute to a

stronger position to act together culture and a strong

commitment to common goals. The challenges are

not solvable by a single administrative sector or a

single actor alone posed by the complex global

environment. Cooperation insists deep and

committed cooperation between the various

authorities and numerous other actors. Technical

infrastructure, data networks and systems are closely

linked.

Changes in the mind-set and breach of

geographical and operational obstacles are the

prerequisites for cooperation on the marine

environment. Enhancing the understanding of the

various sectors of the horizontal exchange of

information will remove one of the obstacles. The

challenge of sharing information is not the

technology, but trust and ownership of information.

Researchers further research concentrates in the

area of semantic interoperability in the organisation

and individual point of view; how individuals from

different authorities and organisations understand

semantic interoperability and how to improve it?

Another point of interest is validation process; how to

validate the European Union funded projects’

processes and what kind of framework should it be?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project has received funding from the European

Union’s EMFF programme under grant agreement

No EASME/EMFF/2014/1.2.1.2/5/SI2.715264.

Study to promote Finnish National Common

Information Sharing Environment for Maritime

Surveillance (FiN-CISE).

REFERENCES

Alasuutari, P. (1995). Research Culture. Qualitative

Method and Cultural Studies. London: Sage.

Commission of the European Communities. (2006). Green

Paper: “Towards a future Maritime Policy for the

Union: A European vision for the oceans and seas”.

COM(2006) 275 final. Brussels 7.6.2006 Volume II –

Annex.

Dubé, L. and Paré, G. (2003). “Rigor in Information

Systems Positivist Care Research: Current Practices,

Trends and Recommendations”. MIS Quarterly, Vol. 4,

No.27, pp. 597 – 635.

EUCISE 2020. 2(015a). Project meeting: “EUCISE 2020,

European testbed for maritime common information

sharing environment in the 2020 perspective”.

EUCISE 2020, European Test bed for the Maritime

Common Information Sharing Environment in the 2020

perspective. (2015b). Project Grant Agreement.

EUCISE 2020. (2015c). Work Package 3: Deliverable

D3.1: Partners Cooperative plan pp. 11 – 15.

European Commission. (2010a). Communication from the

Commission to the Council and the European

Parliament on a Draft Roadmap towards establishing

the Common Information Sharing Environment for the

surveillance of the EU maritime domain. COM(2010)

584 Final. Brussels 20.10.2010.

European Commission. (2010b). Report of the workshop on

“Interoperable communications for Safety and

Security”. Gianmarco Baldini. 28-29 June 2010.

European Commission. (2014a). Communication from the

Commission to the European Parliament and the

Council, Better situational awareness by enhanced

cooperation across maritime surveillance authorities:

next steps within the Common Information Sharing

Environment for the EU maritime domain, Report

COM(2014) 451 final.

European Commission. (2014b). The development of the

CISE for the surveillance of the EU maritime domain

and related Impact Assesment. Part2: Combined

Analysis, viewed 25 July 2017, <

https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/sites/maritimeaffai

rs/files/docs/body/cise-ia-study-part2-combined-

analysis-final_en.pdf>.

European Commission. (2017). Maritime Affairs,

Integrated Maritime Policy, vieved 10 June 2017,

<https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/policy_en>

European Parliament. (2011). Regulation (EU) No

1255/2011 of the European Parliament and of the

Council. Official Journal of the European Union.

European Union. 2011. European Interoperability

Framework (EIF); Towards Interoperability for

European Public Services. ISBN 978-92-79-21515-5.

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European

Union.

FIMAC. (2014). Finnish Maritime Authorities Cooperation

leaflet.

FiNCISE. (2015). Study to Promote Finnish National

Common Information Sharing Environment

Surveillance. FiNCISE consortium kick-off meeting

memo.

Finnish Border Guard. (2014). Test Project on cooperation

in executing various maritime functionalities at sub-

regional or sea-basin level in the field of integrated

maritime surveillance (CoopP). Final Report, March

2014. Paris: Elan Graphic. ISBN: 978-952-491-901- 2.

Finnish Border Guard. (2015). FiN-CISE application form

to European Commission, European Agency for Small

and Medium Enterprises (EASME).

Hirsjärvi, S., Remes, P. and Sajavaara, P. (2007). Tutki ja

kirjoita. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Tammi.

Huttunen, M. and Metteri, J. (eds.). (2008). Thoughts on

qualitative research on operational skills and tactics.

Transl. Ajatuksia operaatiotaidon ja taktiikan

laadullisesta tutkimuksesta. The National Defence

University, Department of Warfare. Publication serie 2

no 1/2008. Helsinki: Edita Prima Oy.

IEEE, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

(1990). IEEE Standard Computer Dictionary: A

Compilation of IEEE Standard Computer Glossaries.

New York, NY.

JRC, Joint Research Centre. (2017). Status of the

Interoperability Projects under the 2014 Call.

Coordination meeting for the Projects funded under the

call “Interoperability improvements in Member States

to enhance information sharing for maritime

surveillance” March 14, 2017, Brussels.

Järvinen, P. and Järvinen, A. (2004). On research Methods,

Tampere: Opinpajan kirja.

Laaksonen, A. (2017, June 28). FiNCISE project: Goals and

objectives. Presentation at Laurea University of

Applied Sciences on Maritime Integrated Surveillance

Services (MARISA) User Community and Innovation

Management Meeting.

Luis, FL, Derrick DC, Langhals B, and Nunamaker JF.

(2013). Collaborative cross-border security

infrastructure and systems: Identifying policy,

managerial and technological challenges. International

Journal of E-Politics (IJEP). 4(2), 21-38.

Luokkala, P. (2009). Shared Contexts in METO – co-

operation. Master’s Thesis. Helsinki University of

Technology, viewed 10 July 2017,

<builtenv.aalto.fi/fi/midcom-

serveattachmentguid.../2009_luokkala_p.pdf>.

MARISA, Maritime Integrated Surveillance Awareness.

2017. Grant Agreement: 740698 – MARISA - H2020-

SEC-2016-2017/H2020-SEC-2016-2017-1.

Ministry of the Interior. (2016). Government report on

Internal Security. Publication 8/2016. In Finnish.

ISBN: 978-952-324-084-1. Helsinki: Lönnberg Print &

Promo.

PERSEUS. (2015). Protection of European Seas and

Borders through the Intelligent Use of Surveillance.

Final report, July 2015.

Prime Minister’s Office. (2017). Government Defence

Report. Publication 5/2017. In Finnish. ISBN: 978-952-

287-370-9. Helsinki: Lönnberg Print & Promo.

Rajamäki J. and Knuuttila J. (2015). Cyber Security and

Trust - Tools for Multi-agency Cooperation between

Public Authorities. In Proceedings of the 7th

International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management (IC3K 2015), pp. 397-404. DOI:

10.5220/0005628803970404.

Saaranen-Kauppinen, A. & Puusniekka, A. (2009).

Methodological Education Data Survey – Qualitative

Methods in Network Textbook . Menetelmäopetuksen

tietovaranto – Kvalitatiivisten menetelmien verkko-

oppikirja. In Finnish, viewed 12 July 2017,

<http://www.fsd.uta.fi/menetelmaopetus/>.

Taitto, P. (2007). In Taitto, P., Heusala, A-L. & Aaltonen,

V. Authorities cooperation: Good practises. Transl.

Viranomaisyhteistyö – hyvät käytännöt.

Pelastusopiston julkaisu 1/2007. ISBN 978-952-5515-

37-4.

Tikanmäki, I., Tuohimaa, T. & Ruoslahti, H. (2012),

Developing a Service Innovation Utilizing Remotely

Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS), International Journal

of Systems Applications, Engineering & Development,

Issue 4, Volume 6, 2012.

Tuohimaa, T., Tikanmäki, I., and Rajamäki, J. (2011).

Cooperation challenges to public safety organizations

on the use of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS),

International Journal of Systems Applications,

Engineering and Development, Issue 5, Volume 5,

2011 pp. 610-617.

Tuomi, J. and Sarajärvi, A. (2004). Qualitative research

and Content Analysis. Jyväskylä: Gummerus 0y.

Valtonen, V. 2010. Collaboration of Security Actors – an

Operational-Tactical Perspective. National Defence

University, Department of tactics. Dissertation.

Helsinki: Edita Prima Oy.

Vuorisalo, V. (2012). Developing Future Crisis

Management - An Ethnographic Journey into the

Community and Practice of Multinational

Experimentation. Dissertation. University of Tampere.

Juvenes Print: Tampere.

Yin, R. (2009). Case Study Research. Design and Methods,

London: SAGE Publications.