How to Improve Business Performance: A Financial Analysis on

Micro Tapioca Industry

Febtri Wijayanti, Fithria Novianti, Mirwan A Karim, Arie Sudaryanto, Carolina Carolina

Center for Appropriate Technology Development - Indonesian Institute of Sciences

Keywords: Tapioca, market collaboration, delayed sales, working capital, small scale producer.

Abstract: Village tapioca starch production is an important economic activity in cassava value chain benefitting

manufacturers and cassava farmers. There are 6 small units actively running in Subang West Java Indonesia

capable to produce only 15 ton/month of tapioca. The limited capacity causes them to face stuck in sales

situation from time to time, since marketing is performed individually and it makes them difficult to meet

required quantity of product procurement fixed by middlemen. This problem remains for decades and makes

it difficult for small tapioca producers to grow competitively. In order to find appropriate solution, a case study

was conducted to reveal the underlying predicament. Based on financial analysis to the processing technology,

it can be concluded that tapioca producer with the capacity less than 1 ton a day is burdened by high production

cost. To meet the requirement fixed by middleman who procure minimum quantity of 2 tons tapioca, the best

approach to solve this problem is by establishing a marketing collective action. The scenario shall be to create

groups enabling them to sell the product as frequent as once in every 2 days to improve conversion rate. Most

effective system would be a group of 5 to 7 tapioca small scale producers, providing they agree upon group’s

mission benefitting all members. The tapioca producers group will enable them to also obtain not only market

access, but also access to technology, finance and other supporting policy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cassava has an important role in agriculture

commodity in Indonesia. It has second biggest

productivity beside rice. Not only used for food, but

also to feed and bioenergy. With the extent of use of

cassava, it should be able to become an agro industry

commodity to increase society welfare, especially for

cassava farmers. The added value of agricultural

commodity should become the source of just and fair

prosperity gain for those who are involve in the

activity (Wilkinson; Dongan, Mior, 2011). This study

explores cassava potential as one of important

commodity for agricultural community in providing

prospective value add as tapioca starch. The

production process of which could be performed by

various level technology and scale as well. Making it

one of a potential agro industrial activity to support.

Gandhi, Kumar, and Marsh (2001) stated that in

order to achieve successful agro industry, at least

there are 6 prerequisites to fulfill, i.e. 1) incentive for

farmers as main producer, 2) provision of agriculture

input and determine who will bear the loss, 3) access

to technology 4) visionary consumer behavior

relevant to market effectiveness, 5) attractiveness of

investment 6) attention to organization, asset

ownership, business management, and quality

control. As a business unit, small scale tapioca

industry are inflicted with those problems. More

specific venture tribulations are: 1) lack of

appropriate drying technology, 2) irregular raw

material supply, 3) low efficiency due to the business

scale, 4) market limited option.

Agroindustry development requires effective

business association between farmers and

manufacturers regardless of the size (Rebeca,

Jonsson, Knutsson, 2013). It commonly found that

position of agriculture based small industry in the

supply chain management is weak. Unequality in

socioeconomic status resulted in failure to create

business linkage among potential actors. In reference

to latter, this study focuses on business management

of small scale tapioca industry in Tanjungsiang

Subdistrict of Subang District to unearth the causal

factor of low conversion rate of product into cash

experienced by them. Revealing the case will direct

us to discover strategic solution of the problem to

productively trigger achievement of improved

business performance which the source of income for

those who are involved in cassava value chain

240

Wijayanti, F., Novianti, F., Karim, M., Sudaryanto, A. and Carolina, C.

How to Improve Business Performance: A Financial Analysis on Micro Tapioca Industry.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship (ICEEE 2017), pages 240-246

ISBN: 978-989-758-308-7

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

The research about the dependency of SMEs to

market provider (middleman) has been done by many

researcher. Chau, Goto, Kanbur (2001) conducted a

study about the role of middleman as a bridge to reach

consumers more widely, despite the negative stigma

that middleman considered taking profit too much.

Shorten the chain is one of alternative solution. The

other problem of SMEs are selling. In the tapioca

micro industry, time required to sell the product

approximately 1 month. During the time, they should

provide production cost. Provide operational cost for

1 month is being their problem.

Cooperation and collaboration concept by

Schutze, Baum, GanB, Ivanova, Muller (2011) as a

success solution for SMEs. Ignatiadis, Briggs,

Svirskas, Bougiouklis, Koumpi (2007) introduce a

collaborative business model for the (European) ERP

industry of SMEs through PANDA project. In

reference to latter, this study focuses on business

management of small scale tapioca industry in

Tanjungsiang village of Subang District to unearth

the causal factor of low conversion rate of product

into cash experienced by them.

2 METHODS

2.1 Time and Location

The study was conducted in Tanjungsiang Subdistrict

which administratively is part of Subang District of

West Java Province. The area selected is well known

for its cassava agro ecosystem owned and managed

by local farmers. Field observation was carried out in

2 periods i.e. July-September 2014, and February to

July 2016.

2.2 Method

In order to achieve the objective, this study was

arranged to use a case study approach. Case study

allows us to reveal a complex phenomenon in a

limited observation space (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Quantitative data was collected by a survey to 6

tapioca industries as listed on official Village Data,

followed by qualitative data collection to 2

representative small scale industries in study location.

Technique used in primary data collection was in

depth interview utilizing guided questions and direct

field observation. Quantitative data was then used to

construct financial analysis of the venture.

Descriptive analysis was employed to further

elucidate the phenomenon, specifically relevant to

tapioca production technology and the business

activity.

Analysis Approach using financial analysis,

which data and information of production process in

Tapioca industries processed into balance sheet. From

financial report it can be seen the weakness from the

production system and the cycle of sales of tapioca.

Based on it, the strategic recommendation is made.

The discussion is focused on the problem of

capital utilization which effectiveness is indicated by

business cash flow. Assuming there is not much

change in productivity except price of raw materials

during high and low session, depiction of 12 months

production activity is projected to 5 year. Looking at

the cash flow will enable us to depict and predict the

prospect of capitalization; and further recommend a

strategy to improve the business performance.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Local Trade System of Tapioca

Tanjungsiang Sub District in Subang Area is known

for its cassava production. Supported by its agro

ecosystem, Gandasoli, together with Rancamanggung

village in Tanjungsiang become prominent cassava

cluster. Cassava harvested area in Tanjungsiang

District reach almost 500 hectares, and the land

productivity about 20 tonns per hectare

(Tanjungsiang SubDistrict Profile, 2012). Most of the

cassava is used as raw material for food processing,

i.e chips and “peuyeum” or fermented cassava.

Important to mention, is utilization of small size

cassava tuber called “sampeububuk” for tapioca

production.

In Tanjung Siang Subdistrict of Subang, there are

6 tapioca producers. As a village popularly known for

its good quality of cassava produced by local farmers,

tapioca producers becomes an important part of the

product’s supply chain. Tapioca producers absorb

smallsize cassava or “sampeububuk”, a low valued

product that is not utilized by other food processing

units. The price of smallsize cassava, the main raw

material for tapioca producers, is around IDR600 to

IDR1000/kg. Price fluctuates depend on the season.

The quantity of raw material input differs among

producers. It depends on the amount of money readily

utilized as business capital. From 1 ton of raw

material, they can produce 220250 kgs of tapioca.

The process of tapioca production from peeling,

washing, grinding and milling takes only 5 hours. The

crucial time required in traditional tapioca production

system is drying which depends on climate. During

How to Improve Business Performance: A Financial Analysis on Micro Tapioca Industry

241

dry season, it will take 2 days in average; and

eventually longer in rainy season. Dry starch is then

stored, and it will be sold when the quantity reaches 2

tons. The minimum quantity fixed by middleman for

he utilizes truck capacity as standard. For small scale

tapioca producers, the minimum quantity of tapioca

collection to sell means prolonged time to store and

worst of all, low conversion rate of product into cash.

They will keep the milled produce in “sedimentation

ponds” or the dry flakes in their storage for one month

before they finally have sufficient quantity

The existing marketing systems only provide sale

opportunity once in every 2 weeks. The average sale

frequency of twice in a month allows them to gain

approximately IDR28.000.000, from selling tapioca

and its waste that still bear economic value. On the

other hand, they still have to keep producing tapioca

and this situation is a heavy burden for small scale

industry with low capital. In short, they must have

sufficient cash to support monthly production activity

(Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Production, Stock, and Sales of Tapioca Product

It is shown that every month, sales are always

lower than production. This situation indicates a high

cost of production for conversion rate of product into

cash is low due to the imbalance of production and

sales.

This condition has been going a long time, from

the beginning they start to produce tapioca. Many

times, producer complained about lack of capital,

while, it happen in the situation when fresh cassava

as main raw material is cheap. It could happen

because of no sales activity. It means they have no

cash to finance their production. It could happen

because of their sales set to quota of middleman.

Those situations make the stock accumulation in

sedimentation ponds or in warehouse. This

accumulation has a risk of damage.

Despite their high dependency to the middlemen

negatively affects productivity, being independent is

not bearable for marketing cost for small scale tapioca

producers to include transportation are not affordable.

It is therefore the main reason of why they have no

other choice than being controlled by middlemen.

3.2 Investment and Cost of Production

Initial investment or fixed cost is the amount of

money need to be spent to start a business. Based on

financial analysis of small scale tapioca with a

production capacity of one ton a day, initial cost of

IDR 74.325.000 is needed to construct production

facilities, provide tools and equipment and also to

obtain legal business.

In many cases, producer is not count their asset

such as land, house, and water installation as their

initial investment. In the traditional industry, it could

happen. But, in order to this study, we insert it to their

initial investment for analysis. As well as legal

business. In many producer, especially micro small

scale industry, legal business is a things that they

ignored. They worry if they have legal business, they

have to pay the tax. But, without legal business, they

will easily being victimized of “informal tax”, or

being criminalized.

Table 1 below indicates amount of money they

should provide to start the business. In general,

tapioca producer should provide three things, there

are: legal business, unit production, and

machinery/equipment.

Table 1: Initial Infestation of Tapioca Small Scale Industry

No

Description

Unit

Total (IDR)

Lifetime

(Month)

1.

License

1.200.000

2.

Unit Production

Land Rent

1

3.000.000

12

Production Room

1

3.000.000

12

Electricity

Installation

1

1.500.000

12

Water Installation

1

2.500.000

12

Water Pump

1

2.500.000

24

Precipitation Pool

3

22.500.000

60

3.

Equipment and Machinery

Gauze

2

2.000.000

12

Drying Rack

25

5.000.000

12

Bamboo Woven

Tray

800

16.000.000

12

Grater

50

1.125.000

24

Filter

1

8.000.000

24

Washer

1

6.000.000

60

Total Infestation Cost

74.325.000

Source: Primary Data, Processed

On the other hand, cost of production for tapioca

business with the capacity of 600 quintal a day is

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

242

approximately IDR20 million depends on raw

material price. The amount of money sufficient to

provide raw material, workers, other supporting

materials and utilities. Raw material cost takes about

78,3% of overall cost. It indicates in Table 2.

Table 2: Production Cost of Small Scale Tapioca Industry

(600kw/batch)

No

Description

Total Cost/Month

(IDR)

%

1.

Raw Material (Cassava)

12.800.000

62.64 %

2.

Packaging

416.000

2.04%

3.

Labor

3.320.000

16.25%

4.

Utility

50.000

0.24%

5.

Other Expenses

3.848.802

18.83%

Total Production Cost

20.434.802

100.00%

To be able to have a continuous production

activity, a business entity should provide enough

money to cover several activities in a row. In the case

of small scale tapioca producer in Tanjungsiang

Subdistrict, when sales can only be done once a

month, the amount of working capital should then be

provided to support 4 production activities. To have

sufficient amount of money, they usually use the help

of money lenders; and paying it back when the

product is successfully sold.

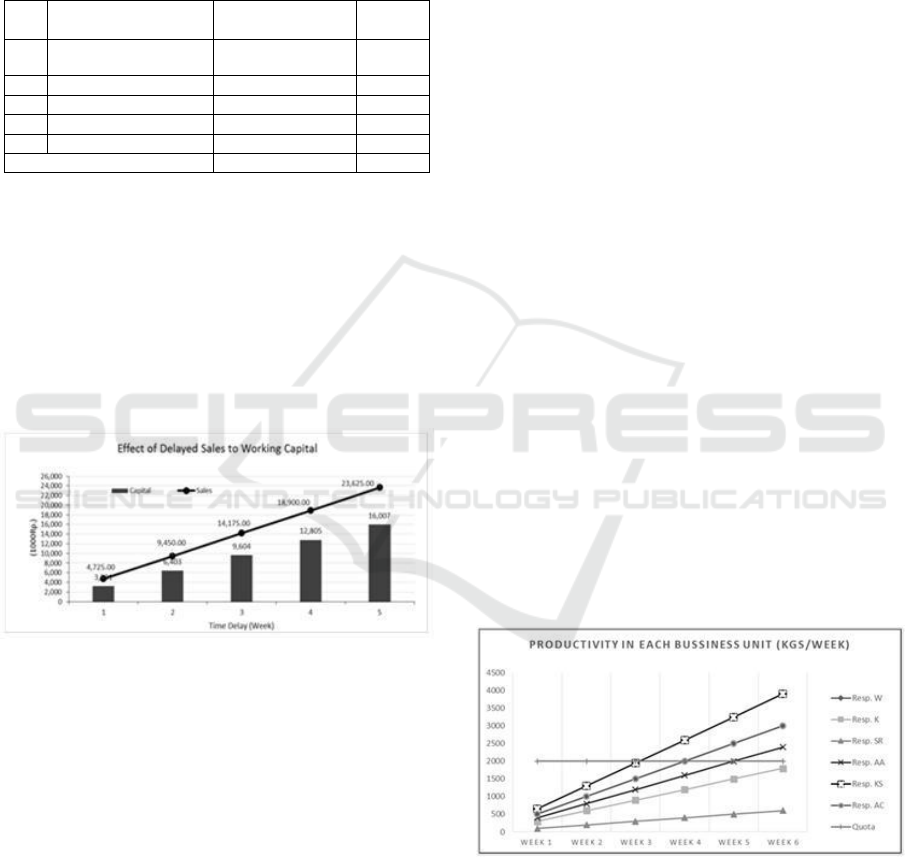

Figure 2: Effect of Sales Delay to Working Capital

The graph in Figure 2 indicates the amount of

money needed by the small scale tapioca producer to

have continuous activity. Present situation in which

sales is only achieved in delayed time, the amount of

capital needed becomes higher. Two week delay will

cost them Rp. 6,403,000, and the more delayed time

of sale, the more money required for them to support

production activity.

Because working capital is usually obtained from

the middlemen, the consequences is they have to pay

higher price of money. The business relationship cost

them a low bargaining power in product marketing in

which standard price is usually determined by the

middlemen. In the long run, this condition limits

tapioca producers to gain sufficient profit and benefit

as they are supposed to earn.

3.3 Collaboration as Strategic

Recommendation

Lack of capital is one of problem of the small scale

tapioca producer. They don’t realize that their lack of

capital are happened because of the sales system,

which occur from time to time. Entrepeneurs

knowledge traditionally cause small scale tapioca

producers do not accustomed to recording their

expenses and sales in detail, doing market research,

and making sales plan.

The problematic delayed sale is a decade long

problem encountered by small scale tapioca producer

in Tanjungsiang Subdistrict. Their limited working

capital and storage space causing have placed them

into a situation which hamper their business growth.

There are cases of business closure due to this

unsolved situation. This is the underlying reason of

stagnant quantity of tapioca producers in

Tanjungsiang Subdistrict. Practically there is no

supporting scheme implemented to solve this

particular problem.

Six tapioca producers in Tanjungsiang Subdistrict

are able to survive despite many limiting factors.

Maximum production capacity performed by this

study respondent, KS, is 650 kgs dry tapioca/week.

Smaller scale, owned by SR, is able to produce only

100 kg tapioca/week. Based on the sale pattern

determined by 2 tons quota set by middlemen, KS

suffer delayed sale for 3 weeks and worst case may

reach 10 weeks. Figure 3 depicts the dynamics of

productivity contrasted with sale quota.

Figure 3: Productivity Each Responden (Kgs/week)

SMEs are in need of marketing knowhow to

determine proper markets and customers for their

products and to improve design and quality

parameters (Aykan;Aksoy;Sonmez, 2013). For SMEs

the best way for them to enter new markets is to

establish alliances with other SMEs - or with larger

How to Improve Business Performance: A Financial Analysis on Micro Tapioca Industry

243

firms (Robson & Bennet, 2000). In the case of small

scale tapioca producer who have no other option or

more appropriately said is lacking access to

alternative market has caused placed them on

stagnation. Individual marketing effort is eventually

cost them more and the situation makes lower profit

gain; but it seems that they do not have a proper

solution.

Marketing collaboration can become a proper

solution for small scale tapioca businesses. Although

not a new concept, networking could be the most

appropriate strategy for small scale industries to

develop strong business capable to compete.

Collaboration allows business to manage risk through

sharing scheme, provide access to resources so that

improvement of business performance can be

achieved (Chakraborty; Bhattacharya;

Dobrzykowski, 2014). Collaboration will help small

scale businesses like the tapioca industries in

Tanjungsiang Subdistrict to have competitive

advantage. Financial analysis indicates that

collaborative scheme implementation will help them

to gain more profit and benefit as well, among others

broader market option and higher bargaining position.

No delay sales can be achieved, and thus, cash

availability could be better due to improved

conversion rate.

Collaboration is a process in which those who are

involved share information, resources and other

responsibilities to plan, implement and evaluate the

activity; in other word, collaboration is an

arrangement to work together

(Camarinha&Afsarmanesh, 2006). Collaboration

among tapioca producers in Tanjungsiang Subdistrict

is prospective to be established. Economically the

strategy is advantageous because: Sales can be

performed in a shorter period or higher sale frequency

is obtained, Higher sale frequency means faster

turnover rate, turn the product into cash, Less

working capital is needed

It is shown in Figure 3 that is sales can be done

every week, working capital needed is only

IDR3.201.000,- depend on the capacity, which can be

used to cover the cost of the week after production

activity. Through collaboration, sales period can be

shortened to become 1 week only rather than 2 weeks.

Collaboration scenario based on each tapioca

producer capacity. For the information, in

Tanjungsiang Subdistrict, 6 unit small scale tapioca

industry have different capacity depends on their

ability to provide initial investment. The idea of

collaboration can be done without limiting their

production capacity. Based on the producers

information, we account that with the average of their

productivity, the group can collecting and selling

tapioca to middleman in every 1 week as shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Small Scale Industry Collaboration in Market

According to Coulter (2007), collaboration of

small development, however there are drawbacks that

should be anticipated as mentioned by Jonathan

(2007) as “hidden cost” i.e. : Lost of autonomy to buy

and sell certain quality of product, as well as decision

to choose buyer and selling time; Lost of time for

groups meetings and consolidation; Cost of

establishing same perspective, principle and behavior

among members; and also to construct and implement

rewards and punishment system as a commitment.

In order to reduce high cost of proposed

collaboration system, social capital becomes an

important key element to humanistic economic

development. Important factors embedded in social

capital are among others valuable social relation,

plausible social transformation and established social

network. Due to its significance role in improving

economic achievement, it is therefore important to

gain thorough understanding of human interaction

complexity (Vallejos; Macke; Olea; Toss, 2008).

Villagers in general, still hold the principle of

social interaction in which family relation becomes

valuable bond. And this is found in Tanjungsiang

Subdistrict, especially among farmers where

collective action is still performed in many

agricultural management activities (Carolina

&Novianti, 2016). This is a strong foundation for

Tanjungsiang Subdistrict community to establish a

collaborative network for economic purposes.

Reinforced by a good institutional development,

collaboration among small scale tapioca producers is

a prospective proposal.

Figure 4. Small Scale Industry Collaboration in

Market

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

244

It is expected that collaboration will be

established not only for product marketing, but also

include the whole production system. As part of the

supply chain, small scale tapioca production unit

should possess better bargaining position in cassava

industry. Collaboration will enable them to be

exposed to a broader market, and other benefits such

as possibility to cost share and opportunity to

technology transfer in order to improve productivity

and business performance. However, collaborative

network will not be achieved without trust among

members (Petrescu; cRuz; Negrusa, 2014). An

important point which possible to attain in a

community with strong social capital.

It is fair to conclude that the character of small

scale enterprise in rural area is traditional in which

their natural resource base activity is heavily depend

on raw material availability and local market system.

In globalization era, holding to that principle will

place them into a vulnerable position. It is important

to strengthen them with relevant entrepreneurial skill

and knowledge to help them survive by increasing

their competitiveness. This will require a collective

action and institutional approach to shift the paradigm

from traditionally managed small scale enterprise to

collaborative network. The collaboration of which

will enable them to strengthen their bargaining

position, solving problem collectively, which at the

end creating a more efficient and effective marketing

system (Barham &Chitemi, 2009). Proper support is

required to increase the capacity and capability of

small scale industries to adapt well into meeting

market demand and thus establish sustainable

business activity they could rely upon (Aykan;

Aksoy; Sonmez, 2013).

Of course, to realize the idea of collaboration,

there should be one of tapioca producer who

pioneered. Communication between producers is

absolutely necessary. Intensive communication and

meetings required to equalize perception and group

purpose. In this part, the role of facilitator is

necessary. Facilitator has an important role to be a

mediator to make similarity understanding.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Delayed sales is one of the problem of small scale

tapioca producer, especially in Subang Region. It is

need problem solver to cope that condition.

Collaborations could become a prospective

alternative to support the business performance of

small scale tapioca industry. Collaboration can

strengthen them in bargaining power, technology

innovation, and market share. They growth together,

and create an social ties more closely. The existing

social capital plays an important role to establish an

effective knot of collaboration which function not

only to improve marketing system, but also to gain

better access to technology, capital and supporting

policy they deserve.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Center of Appropriate

Technology Development Indonesian Institute of

Science for supporting this study. We also extend our

gratitude to all respondents’ tapioca manufacturers in

Tanjungsiang subdistrict for being diligently

accommodating us with data and information; also to

Hari SiswoyoAji, Abah Cumid and all tapioca

producer in Subang, who have contributed in many

aspects of the research.

REFERENCES

Aykan, Ebru; Aksoy, Semra; Sonmez, Ebru. 2013. Effects

of Support Programs on Corporate Strategies of Small

and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences 99 pp. 938 – 946, Elsevier, 9th

International Strategic Management Conference.

Barham, James, and Chitemi, Clarence. 2009. Collective

action initiatives to improve Marketing performance:

Lessons from farmer groups in Tanzania.Food Policy

34, pp. 53–59. Elsevier.

Baxter, P, and Jack, S. 2008. Qualitative Case Study

Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for

Novice Researchers. The Qualitative Report Journal,

No. 4, Vol. 13, pp. 544-559.

Camarinha-Matos, Luis, M., Afsarmanesh, Hamideh. 2006.

Knowledge Enterprise: Intelligent Strategies In Product

Desain, Manufacturing, and Management.International

Federation for information Processing (IFIP), Volume

207, eds. K. Wang, Kovacs G., Wozny M., Fang M.,

(Boston: Springer), pp.26-40.

Carolina, Novianti, Fithria. 2016.Farmers Coadaptation in

Agroecosytem Management of Cassava Cultivation in

Rancamanggung Village – Subang District.

JurnalManusiadanLingkungan, Vol.23, No. 2, pp.241-

248.

Chakraborty, Samyadip., Bhattacharya, Sourab.,

Dobrzykowski, David.D. 2014. Impact of Suplly Chain

Collaboration on Value Co-Creation and Firm

Performance: A Healthcare Service Sector Perspective.

Procedia Economics and Finance 11 pp 676-694.

Chau, Nancy H., Goto, Hideaki., Kanbur, Ravi. (2016)

Middleman, Fair Trade, and Poverty. The Journal of

Economic Inequality. Vol. 14 issue 1, pp 81-108

How to Improve Business Performance: A Financial Analysis on Micro Tapioca Industry

245

Coulter, Jonathan. 2007. Farmer Groups Enterprises and the

Marketing of Staple Food Commodities in

Africa.CAPRiWorking Paper No 72.

Gandhi, Vasant., Kumar, Gauri., Marsh, Robin. 2001.

Agroindustry for Rural and Small Farmer

Development: Issues and Lessons from India.

International Food and Agribusiness Management

Review, 2(3/4): 331–344, Elsevier Science Inc.: 1096-

7508.

Ignatiadis I., Briggs J., Svirskas A., Bougiouklis K.,

Koumpis A. (2007) Introducing a Collaborative

Business Model for European ERP Value Chains of

SMEs. In: Camarinha-Matos L.M., Afsarmanesh H.,

Novais P., Analide C. (eds) Establishing the Foundation

of Collaborative Networks. IFIP — The International

Federation for Information Processing, vol 243. pp

505-512. Springer, Boston, MA.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73798-0_54

Petrescu, Dacinia, Crina; cRus, Veronica, Rozalia;

Negrusa, Letitia, Adina. 2014. Attitude of Companies:

Network Collaboration vs. Competition.(Sciencedirect)

Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 148, pp

596-603.

Dare, Rebecca;Jnsson,Hkan;Knutsson,Hans (2013).

Adding Value in Food Production, Food Industry, Dr.

InnocenzoMuzzalupo (Ed.), InTech, DOI:

10.5772/53174. Available from:

https://www.intechopen.com/books/food-

industry/adding-value-in-food-production

Robson, A, J, Paul; Bennett, J, Robert. 2000. SME Growth:

The Relationship with Business Advice and External

Collaboration. (Springer) Small Business Economics,

Vol. 15, No. 3 pp. 193-208.

Schutze, Jens., Baum Heiko., Ganb, Martina., Ivanova,

Ralica., Muller, Egon. (2011) Cooperation of SMEs –

Empirical evidence After The Crisis. Working

Conference on Virtual Enterprises. PROVE:

Adaptation and Value Creating Collaboration

Networks. Pp 257-534. © IFIP International Federation

for Information Processing 2011.

Vallejos,R.V., Macke, J., Olea, P.M., and Toss, E. 2008.

Pervasive Collaboration Networks.IFIP International

federation for Information Processing, Volume 283,

Luis M. Camarinha-Matos, Willy Picard; (Boston:

Springer), pp 43-52.

Wilkinson, John; Dorigon, Clovis; Mior, Luiz, Carloz.

2011. The Emergence of SME Agroindustry Networks

in The Shadow of Agribusiness Contract Farming, A

Case Study From The South of Brazil (Chapter 5).

Innovative Policies and Institution to Support Agro

Industries Development. FAO. Rome. ISBN: 978-92-5-

107036-9

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

246