Evaluating Health Insurance Inequality in Indonesia using

Concentration Curve and Index

Muryani Muryani, R. Dimas Bagas Herlambang, Nurul Aini

Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Airlangga St, Surabaya, Indonesia

muryani2008@yahoo.co.id

Keywords: Health insurance, Concentration index, Kakwani index, National health insurance.

Abstract: Equality in access to health services is one of main concerns in improving the public’s well-being. In

Indonesia, the public administration has tried to achieve this equality by establishing National Health

Insurance (NHI) in early 2014, replacing the older system of public health insurance. The data used in this

study is the Indonesian Family Life Survey, which took place 1 year after NHI implementation. This study

has assessed the inequality in public and private health insurance for public and private health using a

Concentration and Kakwani Index. Furthermore, the sample used was decomposed in to a sub-sample to get

more detailed information. This study found that there is some degree of inequality in public health

insurance, but it is more pro-poor than private health insurance. However, there is evidence from the

decomposed results that shows that there is some room for improving the inequality.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2005, 58

th

World Health Assembly underlines the

need of Universal Health Coverage, to ensure health

financing for every people. Indonesian government

already reach out this issue a year before, by

enacting Law No. 40/2004 about National Social

Security System. This law is the very foundation to

achieve NHI (National Health Insurance) in

Indonesia. The Indonesian government choose

insurance approach rather than market one, prior to

the experiences in cross-country that successfully

implemented in United States of America and China

(World Health Organization, 2010)

In 2014, the Indonesian government’s effort

towards achieving universal coverage in health

insurance has entered a new stage in the

implementation of NHI. It is now in the first stage of

managing the participants, giving priority to

important elements of the public worker sector

including people who already have Health Insurance

and Workers Social Insurance, and the poor. The

next stage is to give access to all people in

Indonesia, which is targeted to be achieved in 2019

(Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2013).

Earlier evaluations of Indonesian health

insurance have already been conducted by Hidayat,

Thabrany (2004) and Pradhan, Saadah (2007) for the

period of crisis from 1997-1998. Another evaluation

was conducted by Vidyattama, Miranti (2014) post-

NHI implementation. These works used the same

factor to assess inequality, which is the access and

utilization for health insurance. The results from

these works show that the access for health

insurance is already pro-poor, but there is some

degree of leakage for public health insurance

utilisation.

This implementation of NHI surely helps the

poor in Indonesia. However, it still needs further

evaluation. One way to do this evaluation is using a

concentration curve and index. Kakwani (1977) used

this method to assess the progressivity of tax. Later

on, these methods were implemented in the health

economics context by Wagstaff, Paci (1991) and

Kakwani, Wagstaff (1997), which together with the

Kakwani index is handy for evaluating progressivity.

Why do the evaluation? Does it help to make a

change to inequality? These questions have been

answered by Wagstaff van Doorslaer (2003) using

the decomposition method. In their works, they

noted that the decomposing method could answer

the three problems that arise in health inequality.

First, the inequality of some of the variables might

stem from inequality in the other variables. Second,

there is evidence that inequality is changing over

time (Victoria, et al., 2000; Schalick, et al., 2000),

and one should answer to the factors driving this.

Muryani, ., Herlambang, R. and Aini, N.

Evaluating Health Insurance Inequality in Indonesia using Concentration Curve and Index.

In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association (INAHEA 2017), pages 213-217

ISBN: 978-989-758-335-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

213

The third the most obvious problem in relation to the

evaluation is that we need more information to make

a better-designed policy.

Two decomposing factors that are relevant to

inequality are the health care type and health care

provider type. Between public and private health

care providers, Gertler (2007) noted that there is

evidence of inequality that stems from different

access to high-quality outpatient care caused by

different treatments from the public and private

health care providers. An important factor that needs

to be taken note of in relation to this problem is the

preference of the poor. It was noted by Gertler

(2007) that they prefer public-provided health care.

As for health care type, we began with a price

comparison between inpatient and outpatient care.

Adam and Evans (2006) worked out that when

comparing between the two, the results show that the

ratio between inpatient cost compared to outpatient

cost could range from 2 to 12 times higher. This

suggests that the inequality might be more severe in

inpatient care than outpatient care. But in the same

study, Adam and Evans (2006) also showed that this

factor might be related to the facilities in the

hospital. If the hospital could afford more

technology that would make for better outpatient

care, this would generate a higher outpatient cost.

From that point of view, this article will evaluate

inequality using a concentration curve, concentration

index, and Kakwani index. Using data from the fifth

wave of IFLS (Indonesian Family Life Survey), this

article evaluates the inequality approximately 1 year

after entering the first stage of NHI. Later, this

article decomposed the obtained concentration index

to get more detailed information. The decomposing

factor used has also been provided in this data set.

Different from the previous works, the factors

evaluated in this article relate to the claimed benefit

of insurance. It is used for the claimed benefit to get

a better insight in to the benefit value of insurance. It

is also extending the utilisation findings in the

previous works that still use the number of insurance

claims, and not the value of them.

2 METHODS

Different to the Lorenz curve, the concentration

curve could explain the inequality by connecting

economic inequality with other living standard

variables (O' Donnell, 2008). In this article, the

living standard variable is the claimed benefits of

health insurance. The claimed benefit will be plotted

against the cumulative population proportion in

they-axis and cumulative wealth proportion in the x-

axis sorted from poor to rich. In the Lorenz curve, it

plots the shares of the claimed benefit against

quantiles of the living standards variable.

From the obtained concentration curve, the

concentration index was calculated. The

concentration index formally could be defined as

being twice the area of the concentration curve and

line of equality. A convenient regression to calculate

concentration index was demonstrated by Kakwani,

Wagstaff (1997) obtained by the following formula:

2

ℎ

=+

+

(1)

where

is variance of the rank used,ℎ is claimed

benefit, and is the rank obtained from the wealth

ranking which could be easily obtained through the

computation of the concentration curve.

To obtain the standard error of the concentration

index, Kakwani (1997) derived the standard error for

the individual level data. Their formula resulted

from applying the delta method used by Rao (1965).

Specifically, the formula used was:

=

1

1

−(1−)

(2)

for

=

(

2

−1−

)

+2−

−

, and

=

∑

ℎ

, where is the sample size, and is

the concentration curve ordinate.

After the concentration index was obtained, we

calculated the Kakwani index. This index is useful to

see whether or not the variable is progressive or

regressive in respect to its ATP (Ability to Pay)

measurement. In this case, we will use the Lorenz

curve (O'Donnell, 2008). As used by Kakwani

(1977), the Kakwani index in this article has been

formulated as:

=

−

(3)

where shows the Gini index which representing

ATP.

To obtain a more detailed result, the samples

were decomposed using a method demonstrated by

Wagstaff, van Doorslaer (2003). The decomposing

factor used in this article is the type of health care

(outpatient or inpatient) and the type of healthcare

centre provider (public or private healthcare centre).

Technically, the formula used for decomposing is to

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

214

treat the concentration index for claimed benefit as

having a linear relationship to the concentration

index of the regressor. Specifically:

ℎ=+

+

(4)

where ℎ is the claimed benefit, and represents the

number of regressors used. From this linear relation,

the concentration index can be written as:

=(

̅

/

)

+

/

(5)

where residual component captured by .

The data used in this article is the fifth wave of

IFLS. This survey was conducted in 16,204

households in Indonesia, representing 83% of the

Indonesian population (Strauss, 2016). This dataset

is useful when explaining the claimed benefit of

health insurance, complemented with other

information about health insurance, which is not

provided by other datasets for Indonesia.

3 RESULTS

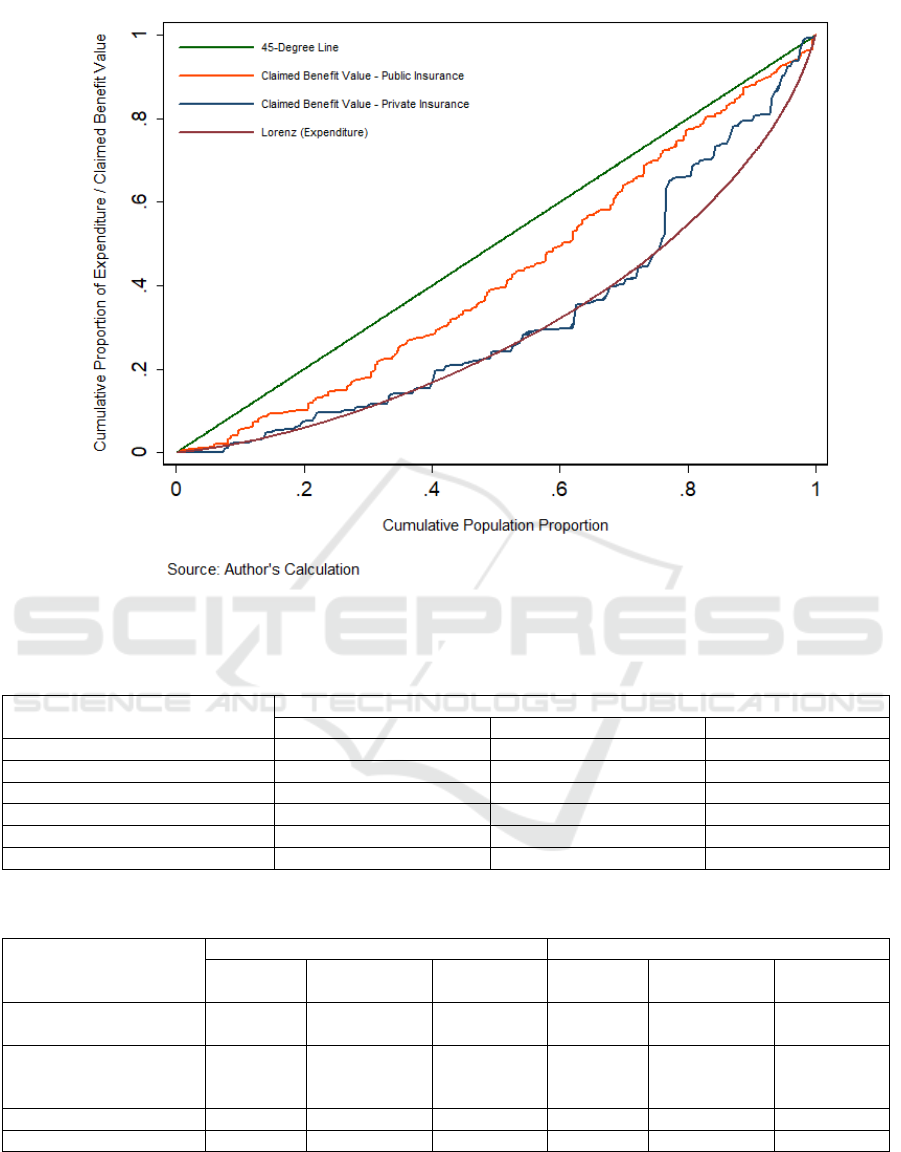

Figure 1 and Table 1 (see Appendix) show the

results for the total and sub-sample of the claimed

benefit. The results of the total sample show that

there is a moderate value of inequality. However, the

results from the sub-sample show the inequality

difference between public and private insurance. It

shows that the inequality between public insurance

is lower than that of the private insurance. These

results are also consistent with the Kakwani index,

which shows that public insurance is more

regressive than private insurance.

Results from the decomposition show that the

type of healthcare is more elastic in public

insurance. In public insurance, the type of health

care contributes a positive concentration to the total

value. This means that outpatient care creates more

inequality than inpatient care. This result also

happens in private insurance, but with a higher

contribution to inequality.

The results also show that the type of healthcare

provider is more elastic in private insurance than in

public insurance. In public insurance, the type of

healthcare provider contributes a negative

concentration to the total value. This means that

publicly-provided health care creates more equality

than privately provided care. The magnitude of this

“pro-poor” result is very low. Different results

happen in private insurance, which shows that public

health care centres treat private insurance in a “pro-

rich” way.

4 DISCUSSION

Public insurance shows lower inequality than private

insurance. This result immediately suggests that

public insurance is not implemented as intended, but

if we compare it to the results in private insurance,

then it is more pro-poor. The Kakwani index for

either of the sub-samples also supports this finding.

Public insurance is more regressive than private

insurance, which means that it is more pro-poor in

the perspective of ATP.

Evaluating Health Insurance Inequality in Indonesia using Concentration Curve and Index

215

Figure 1: Concentration Curve of Claimed Insurance Benefit and Lorenz Curve in Indonesia

Table 1: Concentration and Kakwani Index

Insurance Provide

r

Total Public Private

Gini Index 0.3893 0.3799 0.3817

(

0.0078

)

(

.0094

)

(

0.0142

)

Concentration Index 0.2314 0.1439 0.3449

(0.0398) (0.0437) (0.0523)

Kakwani Index -0.1579 -0.2360 -0.0368

N 1203 954 249

Table 2: Decomposition of The Concentration Index

Public Insurance Private Insurance

Elasticities

Concentration

Index

Contribution Elasticities

Concentration

Index

Contribution

Type of Health Care

(Outpatient = 1)

-1.9199 -0.0161 0.0309 -1.4340 -0.0590 0.0846

Type of Health Care

Center (Public Health

Care Center = 1

)

0.0900 -0.0649 -0.0058 -0.1217 -0.1696 0.0206

Residual - - 0.1188 - - 0.2397

Total - - 0.1439 - - 0.3449

Findings from the decomposition method show

that outpatient care is one of the sources of

inequality that happens in public insurance

implementation in Indonesia. This inequality could

be caused by the growing service of healthcare as

noted by Adam and Evans (2006), which expands

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

216

the choice to use inpatient service in-house.

Experience from Vietnam in 1998 also shows that

outpatient care subsidies tend to be more inequal

than the inpatient one (O'Donnell, 2008). Diseases

that are included in this category also usually happen

to charge at very high price, which normally can

only be accessed by the rich.

Results from the decomposition also show that

public healthcare centres could reduce inequality in

their insurance benefits. The low magnitude suggests

that public healthcare centres are still not significant

in relation to reducing inequality. This needs to be

evaluated since the poor prefer to use public

healthcare centres, rather than private healthcare

centres (Barber, 2007). Still, results from the private

insurance sample show that public healthcare centres

are more pro-poor while treating public insurance

holders more than the private ones.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The overall results show that 1 year after NHI

implementation, the public insurance shows a lower

degree of inequality compared to the private one.

This has made public insurance a pro-poor

instrument for health equality, but contribution of

outpatient care as a possible source of inequality in

public insurance should be regulated by the

government.

The decomposition result from the healthcare

provider shows that public healthcare centres are

more pro-poor when treating via public insurance.

This result supports the preference of the poor that

they would rather choose public healthcare centres

over a private one. Since the magnitude of “pro-

poor” is still low, there is still some room for public

healthcare centres to improve the service to public

insurance holders.

Although there is still some room for

improvement, if these results already show that

public insurance are implemented as intended, and

showing a good promise. These results need to be

monitored after full universal coverage takes place

to prepare for any changes in future condition.

REFERENCES

Adam, T., Evans, DB., 2006. Determinants of variation in

the cost of inpatient stays versus outpatient visits in

hospitals: A multi-country analysis. Social Science &

Medicine. 63(7):1700-10.

Barber, SL, Gertler, PJ., Harimurti, P., 2007. Differences

In Access To High-Quality Outpatient Care In

Indonesia. Health Affairs. 26(3):w352-w66.

Hidayat, B., Thabrany, H., Dong, H., Sauerborn, R., 2004.

The effects of mandatory health insurance on equity in

access to outpatient care in Indonesia. Health Policy

and Planning. 19(5):322-35.

Indonesia Ministry of Health 2013. Socialization of

National Health Insurance (NHI) in Social Insurance

National System Handbook. Jakarta: Indonesia

Ministry of Health.

Kakwani, N., Wagstaff, A., van Doorslaer, E., 1997.

Socioeconomic inequalities in health: Measurement,

computation, and statistical inference. Journal of

Econometrics. 77(1):87-103.

Kakwani, NC., 1977. Measurement of Tax Progressivity:

An International Comparison. The Economic Journal.

87(345):71-80.

O'Donnell, O., Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A., Lindelow,

M., 2008. Analyzing health equity using household

survey data: a guide to techniques and their

implementation. World Bank. Washington DC.

Pradhan, M., Saadah, F., Sparrow, R., 2007. Did the health

card program ensure access to medical care for the

poor during Indonesia's economic crisis? The World

Bank Economic Review. 21(1):125-50.

Rao, CR., 1965. Linear Statistical Inference and its

Applications. Wiley. New York.

Schalick, LM., Hadden, WC., Pamuk, E., Navarro, V.,

Pappas, G., 2000. The widening gap in death rates

among income groups in the United States from 1967

to 1986. International journal of health services :

planning, administration, evaluation. 30(1):13-26.

Strauss, J., Witoelar, F., Sikoki, B., 2016. The Fifth Wave

of the Indonesia Family Life Survey: Overview and

Field Report.

Victora, C.G., Vaughan, JP., Barros, FC., Silva, AC.,

Tomasi, E., 2000. Explaining trends in inequities:

evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet.

356(9235):1093-8.

Vidyattama, Y., Miranti, R., Resosudarmo, BP.. 2014. The

Role of Health Insurance Membership in Health

Service Utilisation in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies. 50(3):393-413.

Wagstaff, A., Paci, P., van Doorslaer, E., 1991. On the

measurement of inequalities in health. Social Science

& Medicine. 33(5):545-57.

Wagstaff, A., van Doorslaer, E., Watanabe. N,. 2003. On

decomposing the causes of health sector inequalities

with an application to malnutrition inequalities in

Vietnam. Journal of Econometrics. 112(1):207-23.

World Health Organization, 2010. World Health Report,

2010: health systems financing the path to universal

coverage. World Health Organization. Geneva.

Evaluating Health Insurance Inequality in Indonesia using Concentration Curve and Index

217