Comparing National Health Financing Strategies Amidst Increasing

Mobility Within ASEAN: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia

Jaifred Christian F. Lopez

1

, Ryan Rachmad Nugraha

2

, Don Eliseo Lucero Prisno III

3

1

Associate, Office of Research and Innovation,

San Beda College, 638 Mendiola St. San Miguel, Manila, Philippines 1005

2

Researcher, Center for Health Economics and Policy Studies, School of Public Health,

Universitas Indonesia, Depok City, West Java, Indonesia

3

Associate Professor, Xi’an Jiao Tong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, China

jaifredlopez@gmail.com

Keywords: ASEAN integration, Health financing strategy, Migrant health, Philippines, Indonesia.

Abstract: Health needs within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are expected to become more

mobile as a result of regional integration, thus highlighting the need for a regional consensus on providing

health services to migrants, the need to equip health systems, and the need to harmonize national health

financing strategies. We propose that this harmonization can be facilitated by a contextual comparison of

national health financing strategies, guided by the framework promoted by the World Health Organization.

Using an analysis matrix that synthesized insights generated from literature, we compared the health

financing strategies of the Philippines and Indonesia, two countries with important political and

socioeconomic similarities. Results show that the strategies are predominantly inward-looking, which focus

more on providing various levels of health coverage depending on socioeconomic status and employment,

while lacking mechanisms and a program framework to cover migrants. Thus, while considering the

diversity of government structures and health system capacities within the region, there is a need to develop

a common framework for universal health coverage for migrants, which has to be included in national

health financing strategies within ASEAN.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mobility across the members of the Association of

Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), specifically the

free movement of migrant workers and people

engaged in business, is now at its highest and is

expected to rise further. In 2015, the number of

international migrant workers coming from within

the region amounted to 6.78 million, an increase

from 6.5 million documented in 2013 (ILO, 2015).

This development may be attributed to policy

reforms liberalizing and harmonizing the conduct of

business, trade, education, and employment in the

region, amidst efforts among the ASEAN countries

towards economic integration (ASEAN, 2016a).

Accompanying this development is the need to

plan for emerging health concerns, and achieve

universal health care (UHC), a goal that is consistent

with a strategic measure to “promote strong health

insurance systems in the region (ASEAN,. 2016b).”

In view of the regional goal to facilitate mobility,

this goal implies that ASEAN citizens can freely

move between the member countries with assurance

that their health needs are covered anywhere within

ASEAN. Confirming this implied vision is the

ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint,

which highlights regional strategies for

socioeconomic development, and specifically

mentions the need to “provide guidelines for quality

care and support” for migrants (ASEAN, 2016b).

Difficulty in developing such guidelines is expected,

however, in view of the diversity existing among the

ASEAN countries in terms of economic

development, healthcare situation, and existing

welfare systems for migrants as shown in Table 1,

thus complicating regional efforts.

222

Lopez, J., Nugraha, R. and Prisno III, D.

Comparing National Health Financing Strategies Amidst Increasing Mobility Within ASEAN: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia.

In Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association (INAHEA 2017), pages 222-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-335-3

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

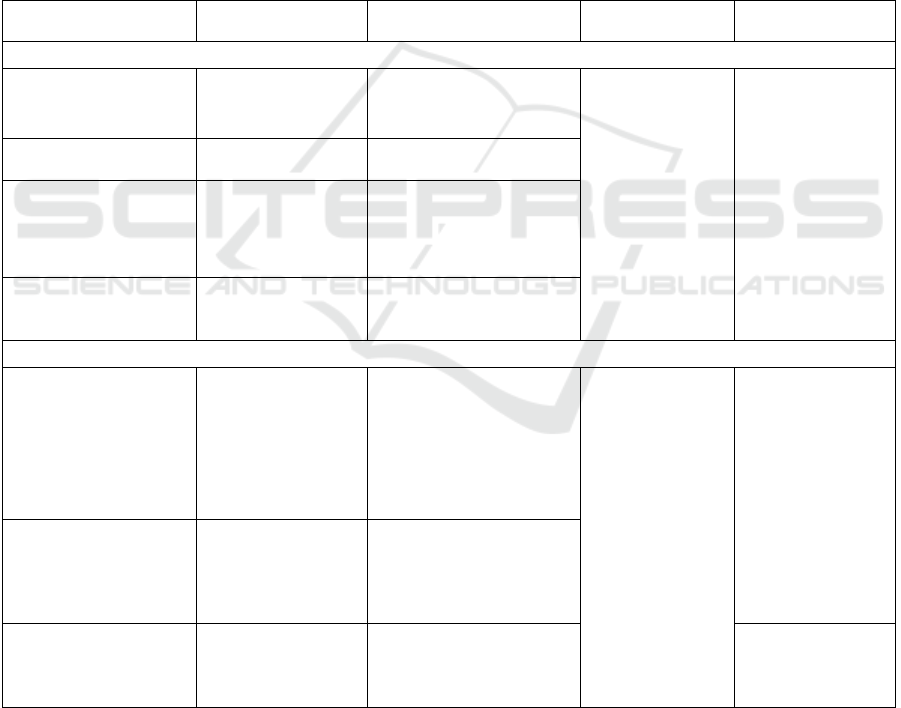

Table 1: Socioeconomic and health indicators of ASEAN member countries (Minh et al., 2014; ILO, 2015)

Population (000s),

2015

Gross National

Income per

capita, 2016*

Total government

expenditure on health as

% of general

government

expenditure, 2015

Out-of-pocket as %

total expenditure on

health, 2014^

Brunei 423 38 520 6.5 6.0

Cambodia 15 578 1 140 6.1 74.2

Indonesia 257 56

4

3 400 5.7 46.9

Lao PDR 6 802 2 150 3.4 39.0

Mala

y

sia 30 331 9 850 6.4 35.3

Myanma

r

53 897 1 190 3.6 50.7

Philippines 100 699 3 580 10.0 53.7

Sin

g

a

p

ore 5 604 51 880 14.1 54.8

Thailan

d

67 959 5 640 13.3 11.9

Vietna

m

93 448 2 050 14.2 36.8

*Determined through Atlas method, World Bank

At the national level, plans for funding UHC are

supposedly included in national health financing

strategies, which are documents that propose policy

directions and plans towards financing the health

needs of the population while preventing widespread

catastrophic health spending (Kutzin et al., 2017). In

keeping with the regional thrust to “provide

guidelines for quality care and support” for

migrants, ideally, national health financing strategies

should pave the way for providing health coverage

for outbound citizens in other ASEAN countries, as

well as addressing the health needs of incoming

ASEAN citizens. Since priority for addressing the

health needs of specific segments of the population

is most clearly manifested by how these are

considered in health policies, analyzing the national

health financing strategies of individual ASEAN

countries can provide valuable insights on

socioeconomic and political contexts that affect the

level of commitment of each member country to a

common UHC regional framework, and thus

facilitate consensus building and implementation.

However, in view of challenges present in the

region, among them the wide disparity of

socioeconomic status and the state of health care

services, this therefore leads to a hypothesis that

policies governing health needs of migrants within

the region only offer a semblance of protection

within the jurisdiction of the home country, without

considering the possibility of a region-wide scope of

health coverage.

With the aim to gather evidence on whether

national health financing strategies envisioned

region-wide coverage for migrants within the

ASEAN region in keeping with the shared goals of

“promoting strong health insurance systems in the

region,” and “providing care and support for

migrants,” this study therefore compared the

national health financing strategies of two ASEAN

countries, the Philippines and Indonesia. These

countries are the primary sources of migrants within

the region, with the aim to identify aspects that can

facilitate the implementation of a regional UHC

framework for the benefit of migrant workers and

persons engaged in business and trade. This study

also reviewed published studies and grey literature

documenting current efforts towards a regional UHC

in both countries and in the region.

2 METHODS

In comparing the two countries, we retrieved the

national health financing strategy documents

published by the Philippine Department of Health

(DOH) and the Government of Indonesia, and used

the guide for developing national health financing

strategies endorsed by the World Health

Organization (WHO) as analytical framework, from

which a comparison matrix was developed. The

WHO guide focused on the following aspects: 1)

strategic interventions, which included revenue

raising, pooling revenues, purchasing services,

benefit design, rationing and entitlement basis, and

alignment issues; and 2) governance-related

concerns, which included implementation

arrangements, evaluation and monitoring plans and

capacity building (Kutzin et al., 2017). Special

attention was given to any provision that intended to

cover migrants and other outbound citizens.

Meanwhile, using PubMed and Google Scholar, we

searched the literature for any supporting studies on

the efforts of both countries in providing health

Comparing National Health Financing Strategies Amidst Increasing Mobility Within ASEAN: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia

223

coverage to their outbound citizens, as well as

similar efforts in other countries within the region.

For the purposes of this review, only English

documents were analyzed.

3 RESULTS

Generally, official documents, published data and

supporting literature showed that the national health

financing strategies of both countries confirmed the

hypothesis that policies for health insurance among

migrants are predominantly inward-looking, in that

the strategies focus on expanding coverage for the

uninsured, providing benefits for dependents of

migrants, and improving the system of

reimbursements and the implementation of benefit

packages and case rates. These efforts have been

spearheaded by the Philippine Health Insurance

Corporation (Philhealth) and the Badan

Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial (BPJS Kesehatan),

which manages the Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional

(JKN, National Health Insurance). Membership

categories exist in both countries as shown in Table

2. This is in addition to the various private health

maintenance organizations (HMOs) in both

countries that offer health services in private

facilities.

Table 2: Public health insurance membership categories in the Philippines and Indonesia (DOH, 2010; JLN, 2017; Pisani,

Kok and Nugroho, 2017)

Membership category Eligibility criteria Contribution Benefits Providers

Philippines

Formal sector (casual

and contractual)

Civil servants,

private employees,

military and police

Payroll contributions

Outpatient and

maternal care

benefit packages

(availed primarily

in accredited

facilities)

Inpatient case

rates

Philhealth-

accredited public

and private

facilities

Overseas Filipino

workers

Registered migrant

workers

Fixed premium

Informal sector

Informal workers,

independent

professionals,

foreign citizens

Voluntary payment of

fixed premium

Indigents (sponsored

program)

Certified poor

households based on

social welfare data

Shared subsidy between

local government unit and

national

g

overnment

Indonesia

Employees:

government/ private

sector

Civil servants,

entrepreneurs,

military, police

Salary deduction.

Government employees:

3% paid by employer, 2%

by employee

Private sector: 4% paid by

employer, 0.5% by

employee

Comprehensive

coverage of

outpatient and

inpatient services

Public and selected

private facilities.

Options vary

according to

premium paid

Self-employed

members

Non-poor self-

employed

Monthly premium paid by

members

Class 1: IDR 25 500

Class 2: IDR 51 500 Class

3: IDR 80 000

Subsidized members

Poor and near-poor

classified by

Ministry of Social

Affairs

Fully subsidized by

national government

Public/select

private facilities

An important difference between the two

countries is how the Philippine national health

financing strategy document specifically mentions

the importance of covering the migrant worker

population, and how the DOH acknowledges the

need to expand benefits afforded them. Meanwhile,

roadmap documents produced by the Government of

Indonesia in partnership with third-party

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

224

development agencies show that while there is an

effort in including the Ministry of Manpower and

Transmigration in consultation meetings, there is no

directly stated goal or aspiration to cover for the

health needs of migrants (JLN, 2017). Thus, for the

purposes of this study, information on covering

Indonesian migrants was retrieved from other

published studies.

In both countries, revenue raising has been

carried out through collection of premiums, either

deducted from regular salaries or voluntarily

contributed, depending on status of employment. In

all these efforts, migrants have been included

through compulsory premium payments, as in the

case of the Philhealth Overseas Filipino Program

and the Indonesian Migrant Worker Insurance

Program (Guinto et al., 2015). Moreover, risk

pooling, which affects revenue raising and the

ability of the health insurance system to purchase

health services, is affected by the fragmentation of

revenue schemes in the two countries, but strategies

have been proposed in both countries to consolidate

these schemes into a unified health insurance fund,

thus reducing fragmentation (DOH, 2010; Pisani,

Kok and Nugroho, 2017).

Additionally, in the Philippines, entitlements

have been limited in a way that prevents the

depletion of pooled funds, thus leading to the

development of benefit packages. Unfortunately,

such limitations have led to insufficient payment for

health services rendered, thus requiring out-of-

pocket payment to cover for the remaining cost. This

is in contrast to a comprehensive coverage being

offered in Indonesia, but provided in specific

facilities depending on the amount of premium paid.

In the case of migrant workers from the Philippines,

while Philhealth provides a mechanism for revenue

collection and health insurance coverage for

dependents remaining in the country and even an

expense reimbursement system for overseas health

facilities, its coverage is mostly insufficient, thus

pushing affected migrants towards catastrophic

health spending, repatriation, and eventual

impoverishment (DOH, 2010) Amidst these

emerging problems, the governments of both

countries have entered into agreements with selected

destination countries to ensure that the health needs

of migrant workers are addressed (Guinto et al.,

2015).

In summary, a system for overseas health

expense reimbursement exists for Philippine migrant

workers enrolled in the national health insurance

program while a similar program is being developed

in Indonesia, but the reality of insufficient

reimbursements highlights the need for a more

effective health financing framework that is also

funded sustainably and sufficiently.

4 DISCUSSION

Though limited by a lack of economic evaluation

and modeling, which may be the topic of a future

study, the study nonetheless presents two lessons for

discussion: 1) that the development of an effective

and sustainable regional UHC framework needs to

consider how it should equitably cover all citizens,

regardless of the economic status of their countries

of origin; and 2) that such a framework may follow

various health financing schemes adopted by similar

international and regional organizations. These

lessons lead to a common message: the need to

develop a common framework to be integrated in

national health financing strategies.

Designing a regional framework that covers both

industrialized and economically disadvantaged

countries must innovate ways to collect sufficient

revenue, create an equitable risk pool, and purchase

health services sufficiently, all while transcending

national boundaries. This leads to asking the classic

question on what kind of health financing system

should be adopted at the regional level: a “socialized

medicine” approach (Beveridge model) financed

through tax payments; a health insurance scheme

funded through salary deductions (Bismarck model);

or the National Health Insurance (NHI) model,

which combines elements of the two aforementioned

models by instituting a single payer mechanism

funded either by taxes or premiums (Wallace. As a

supranational entity, the ASEAN does not have any

authority to collect taxes, thus significantly limiting

the prospects of a socialized regional health care

financing system.

Another possibility is adopting models utilized

by international organizations for field employees.

Particularly, the United Nations offers its employees

a medical insurance plan implemented by a private

HMO through its network of accredited health care

facilities (United Nations, 2017). The ASEAN

Economic Community Blueprint seems to support

this direction as it advocated the involvement of the

private healthcare sector in efforts towards UHC and

the brokering of public-private partnerships for

health (ASEAN, 2016a).

Meanwhile, the European Union (EU), whose

model of economic integration serves as a pattern

for ASEAN, has developed a human rights-based

regional health services framework for migrants,

Comparing National Health Financing Strategies Amidst Increasing Mobility Within ASEAN: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia

225

guided by principles of “availability, accessibility,

acceptability and quality,” through the health-related

provisions of the 2007 Lisbon Treaty and the EU

Consolidated Treaty. These provisions encouraged

EU states to implement policies that are in keeping

with their respective interpretations of the rights

enshrined in the aforementioned treaties, while

preserving “complementarity of health services in

cross-border areas.” While these rights are upheld in

laws in both countries that implement health

insurance systems (DOH, 2010), at the regional

level, the ASEAN itself has developed a strategic

framework on health development where the health

of migrants was stated as a priority, though

regrettably this has not been translated to policy

reforms in all of the ASEAN countries (ASEAN,

2016a; Guinto et al., 2015; Government of

Indonesia, 2017; Fernando, 2011).

Given these considerations, it may thus be

appropriate that an insurance scheme similar to the

National Health Insurance model be considered as a

platform for complementarity between the health

systems of ASEAN countries, while agreeing on a

rights-based framework. The possibility of rolling

out a similar regional scheme may only be realized

through harmonized policy interventions that may

either establish a new system specifically for

ASEAN citizens, or integrate flexibly within the

existing system of the country of destination

(Nodzenski, Phua and Bacolod, 2016).

5 CONCLUSION

Therefore, considering the significant percentage of

migrant workers in ASEAN and the importance of

health coverage in ensuring sustainable economic

productivity, it is in the best interest of the region if

a regional UHC framework can be developed and

adopted, informed by a balance of economic

evaluation, consideration of how health financing

functions can be optimally implemented, and utmost

regard for human rights. Because these

considerations require substantial political will in

each of the ASEAN countries, these factors must be

made part of national-level policy discussions,

integrated in national health financing strategies for

further consideration of national level policy makers,

and included in the agenda for ministerial meetings

and in declarations being adopted in the ASEAN.

REFERENCES

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). 2016.

The ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint.

Available at:

http://www.asean.org/storage/images/2015/November/

aec-page/AEC-Blueprint-2025-FINAL.pdf [Accessed

30 Aug. 2017].

ASEAN. ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint.

2016. Available at:

http://asean.org/storage/2016/01/ASCC-Blueprint-

2025.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug. 2017].

Department of Health, Philippines (DOH). 2010 Toward

Financial Risk Protection:Health Care Financing

Strategy of the Philippines 2010-2020. Health Sector

Reform Agenda – Monographs. Manila, Republic of

the Philippines - Department of Health..(DOH HSRA

Monograph No. 10)[Accessed 30 August 2017].

Fernando F. 2011. ASEAN Strategic Framework on Health

Development (2010-2015): Increase Access to Health

Services for ASEAN People. Available

at:http://www.searo.who.int/thailand/news/asean_healt

h_cooperation_increasing_access_to_health_people_d

r_ferdinal.pdf[cited 30 August 2017].

Government of Indonesia. 2017. Roadmap toward the

National Health Insurance of Indonesa (Ina

Medicare). Available

at:http://www.health.bmz.de/events/In_focus/Indonesi

a_roadmap_to_universal_health_coverage/THE_BRIE

F_EDITION_Roadmap_toward_INA_Medicare.pdf

[Accessed 30 August 2017].

Guinto R, Curran U, Suphanchaimat R, Pocock N. 2015.

Universal health coverage in ‘One ASEAN’: are

migrants included?Glob Health Action8:25749.

doi:10.3402/gha.v8.25749 [Accessed 30 August

2017].

International Labour Organization. 2015. Migration in

ASEAN in figures: the international labour statistics

(ILMS) database in ASEAN [online]. Available at:

http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---

ro-bangkok/---sro-

bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_420203.pdf[cit

ed 30 August 2017].

Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage.

2017. Indonesia: Approaches to covering poor,

vulnerable, and informal populations to achieve

universal health coverage. Available at:

http://www.jointlearningnetwork.org/resources/downl

oad/get_file/ZW50cnlfaWQ6MzU0M3xmaWVsZF9u

YW1lOnJlc291cmNlX2ZpbGV8dHlwZTpmaWxl

[Accessed 30 August 2017].

Kutzin J, Witter S, Jowett M, Bayarsikhan D. 2017.

Developing a national health nancing strategy: a

reference guide. Geneva: World Health Organization;.

(Health Financing Guidance No 3) Available

at:.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254757/1/9

789241512107-eng.pdf [Accessed 30 August 2017].

Minh H, Pocock N, Chaiyakunapruk N, Chhorvann C,

Duc H, Hanyoravongchai P, Lim J, Lucero-Prisno D,

Ng N, Phaholyothin N, Phonvisay A, Soe K,

INAHEA 2017 - 4th Annual Meeting of the Indonesian Health Economics Association

226

Sychareum V. 2014. Progress toward universal health

coverage in ASEAN. Glob Health Action [online], 7:

25856.doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25856. [Accessed 30

August 2017].

Nodzenski M, Phua K, Bacolod N. 2016. New Prospects

in Regional Health Governance: Migrant Workers’

Health in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies [online];3(2): 336–

350. doi:10.1002/app5.113 [Accessed 30 August

2017].

Pisani E, Kok M, Nugroho K. 2017. Indonesia’s road to

universal health coverage: a political journey. Health

Policy and Planning; 32:267–276.doi:

10.1093/heapol/czw120 [Accessed 30 August 2017].

United Nations. 2017. The UN Worldwide Health

Insurance Plan. [online]. Available at:

http://www.un.org/insurance/plans/un-worldwide-

health-insurance-plan[Accessed 30 August 2017].

Wallace L., 2013 .A view of health care around the world.

Ann Fam Med.; 11(1): 84. doi: 10.1370/afm.1484

[Accessed 30 August 2017].

Comparing National Health Financing Strategies Amidst Increasing Mobility Within ASEAN: Lessons from the Philippines and Indonesia

227