Becoming Autonomous Parents in Giving Intervention to Children

with Autism

Is It Possible?

Herlina Herlina and Rudi Susilana

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

herlinahasan_psi@upi.edu

Keywords: Independent Intervention Program, Parent Training, Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Abstract: Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) need intervention to deal with social interaction difficulties.

However, the fact that intervention may cost a lot of money on the one hand and that parents have potentials

to overcome their difficulties on the other hand has inspired initiative to involve parents in giving intervention

to children with ASD. Studies have shown that parent training, social skill training group, and cognitive

behavioral therapy are useful and promising intervention strategies for improving children's social skills. This

study was aimed at studying the effectiveness of parent training in improving of parents’ skills and

independence in designing and implementing the individualized social skills intervention program and the

effectiveness of parental independent intervention in improving children with ASD. This study was carried

out in two phases involving two group of subjects: parents in the training phase and children in the intervention

phase. The results showed that the independent intervention program was effective in improving the parents’

skills and independence in designing and implementing the individualized social skill intervention program

and that parental intervention was effective in improving the social skills of his child diagnosed with ASD.

1 INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently affect

negatively social skills. This has caused children

diagnosed with ASD a lot of problems in their school,

social, and work environments. As a result, they lack

confidence, have low self-esteem, feel anxious and

depressed, and have mental difficulties. Low social

skills also make them prone to bullying. Therefore,

children with ASD need early and intensive

intervention. Early, intensive, and proper intervention

will help them improve social skills (Stone and

DiGeromino, 2014). However, therapy may cost them

a lot of money. Jarbrink et al. (2006) suggest that

autism intervention requires substantial amount of

money. Similarly, according to Wang et al. (2013),

children with ASD need an intensive and long-term

treatment, so the cost becomes greater than that of

other disorder intervention. In this regard, Poling and

Edwards (2014) said that in developed countries

expensive education is often protested because it only

benefits some children. Many advocacy groups, such

as Autism Speaks, The Autism Advocacy Network,

Autism One, Moms on a Mission for Autism, and

Unlocking Autism, are lobbying for politicians to

provide financial support for research and autism

treatment.

A study conducted by Kim et al. (2011) in South

Korea showed that two-third of ASD cases of

research sample taken from a population in general

schools were undiagnosed and untreated. A study by

Salomone et al. (2015) on parents in 18 European

countries showed that in several countries 64% of

children with ASD had never received intervention at

all, 64% received speech and language intervention,

and 55% received intervention of relationship,

development, and behavior. Howell, Lauderdale-

Littin, and Blacher’s (2015) study revealed that 94%

of parents who became the respondents were helpless

in finding intervention for their children because their

ignorance of the availability of such services.

In Indonesia, autism therapies are not affordable

by all. As suggested by the chair of Indonesia Autism

Foundation, Melly Budhiman, a one hour autism

therapy costs about IDR 50K to 250K. Ideally,

autistic children need a four hour therapy a day.

Assuming that a one hour therapy costs IDR 75K, a

month of therapy will cost IDR 7.5 million or around

USD 555 (Media Indonesia Epaper, 2014).

218

Herlina, H. and Susilana, R.

Becoming Autonomous Parents in Giving Intervention to Children with Autism - Is It Possible?.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences (ICES 2017) - Volume 1, pages 218-224

ISBN: 978-989-758-314-8

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

The above explanation shows that it is not easy for

children with ASD to get intervention, but there is no

excuse for not giving them early intervention.

2 PREVIOUS STUDIES

Previous studies showed that parents could be a

reliable resource for early intervention. Parent

participation plays an important role in the giving of

intervention to children with ASD (Negri and

Castorina, 2014; Elder, 2013; Shie and Wang, 2007)

and makes therapy effective and low-cost (Rudy,

2013). The philosophy of treatment in the family

context is to develop the children optimally by giving

them family-centered early intervention (Iversen, et

al., 2003). The family-centered early intervention

aims at improving baby and early childhood

development and minimizing the potentials for

developmental delays through increasing family

capacity in dealing with baby and children with

special needs (Dunst, Bruder, and Espe-Sherwindt,

2014). This aim indicates that parents should be

sufficiently competent in giving effective early

intervention.

Effective early intervention has encouraged

parent training so that the parents can treat their

children at home. Studies have shown that parent

training, social skill training group, and cognitive

behavioral therapy are useful and promising

intervention strategies for improving children's social

skills (Autism Ontario, 2012). Some studies have

shown the advantages of empowering parents in

giving autism intervention; among others are:

facilitating generalization and skill maintenance and

cost-cutting (Relate to Autism, 2010), decreasing

parents’ stressor and increasing optimism

(McConachie and Diggle, 2007), parents can manage

their life, solve problems, and make decisions

effectively (Shie and Wang, 2007), parents become

skillful in implementing their newly learned skills

(Beaudoin, Sébire, and Couture, 2014), and providing

prognosis and better long-term quality of life (Elder,

2013; de Bruin et al., 2015).

However, the common weakness of the

implementation of the offered training programs is

that the parents are only trained to implement

intervention program designed by professional

therapists. Studies have revealed that: 1) the

professionals in parent training program is frequently

viewed as well-trained experts in giving intervention,

so they act as the decision makers in designing

education for children with special needs, and the

parents only act as passive information receivers, 2)

the professionals are too dominant in the parent

empowering program, 3) the program is clinician-

oriented and sometimes does not meet the family

needs, 4) some parents find difficulties in giving

intervention to their children (Shie and Wang, 2007).

Korfmacher et al. (in Dunst, Bruder, and Espe-

Scherwindt, 2014) suggest that many models and

approaches to engage parents in early intervention

program are done as a part of home visit program of

professionals who provide support and training to

parents in improving their children development.

Özdemir (2007) argues that to consistently focus on

parent participation, family service, and early

intervention outcomes, early intervention

practitioners should apply theories and home visit

practice better.

Based on the aforesaid description, it could be

said that in the existing intervention training, parents

still rely on professional therapists in designing

intervention program/curriculum and professional

home visit plays an important role in the

sustainability and the effectiveness of intervention.

When confronted with the limited availability of

professional therapists and the high cost of

curriculum designing, this reliance will potentially

hamper the sustainability of the intervention. On the

other hand, there is no scientific evidence that parents

can be sole intensive behavioral intervention

providers for children with ASD (Tomaino,

Miltenberger, and Charlop, 2014).

Therefore, it is necessary to design an intervention

program that is not only beneficial for children

development, but also can train parents’ self-reliance

in developing, implementing, and evaluation an

intervention program. The self-reliance, the

researchers assume, not only can make intervention

effective and efficient, but also sustainable and

responsive to the progress of the children.

The solution is to empower parents’ self-reliance

in designing and giving intervention to the children

with ASD. There are two major things to train to the

parents: conceptual understanding about ASD, social

skills, intervention, and individual intervention

program and practical skills in designing the program

and techniques of individualized intervention. And

the professionals train the parents’ self-reliance

through training, workshop, mentoring, and

monitoring the implementation of intervention. In

addition, parent empowerment should take into

account the following aspects of adult people: (1) the

need of parents to know what to train, why they

should participate in the training, and how the training

is implemented, (2) parents’ concepts about their self-

reliance and skills in the training, (3) parents’

Becoming Autonomous Parents in Giving Intervention to Children with Autism - Is It Possible?

219

background experience, (4) parents’ readiness to

participate in the training, (5) parents’ motives in their

participating in the training, and (6) parents’ learning

motivation (Knowles, Holton, and Swanson, 2005).

A well-designed and well-implemented

empowerment program is expected to improve

parents’ self-reliance in designing, implementing,

and evaluating social skill intervention program for

their children in accordance with the natural condition

of their children and family. That way, the

intervention will continue be sustainable and develop

in accordance with increasing environmental demand

for children. As a result, children’s social skill will

continue to develop in accordance with their needs.

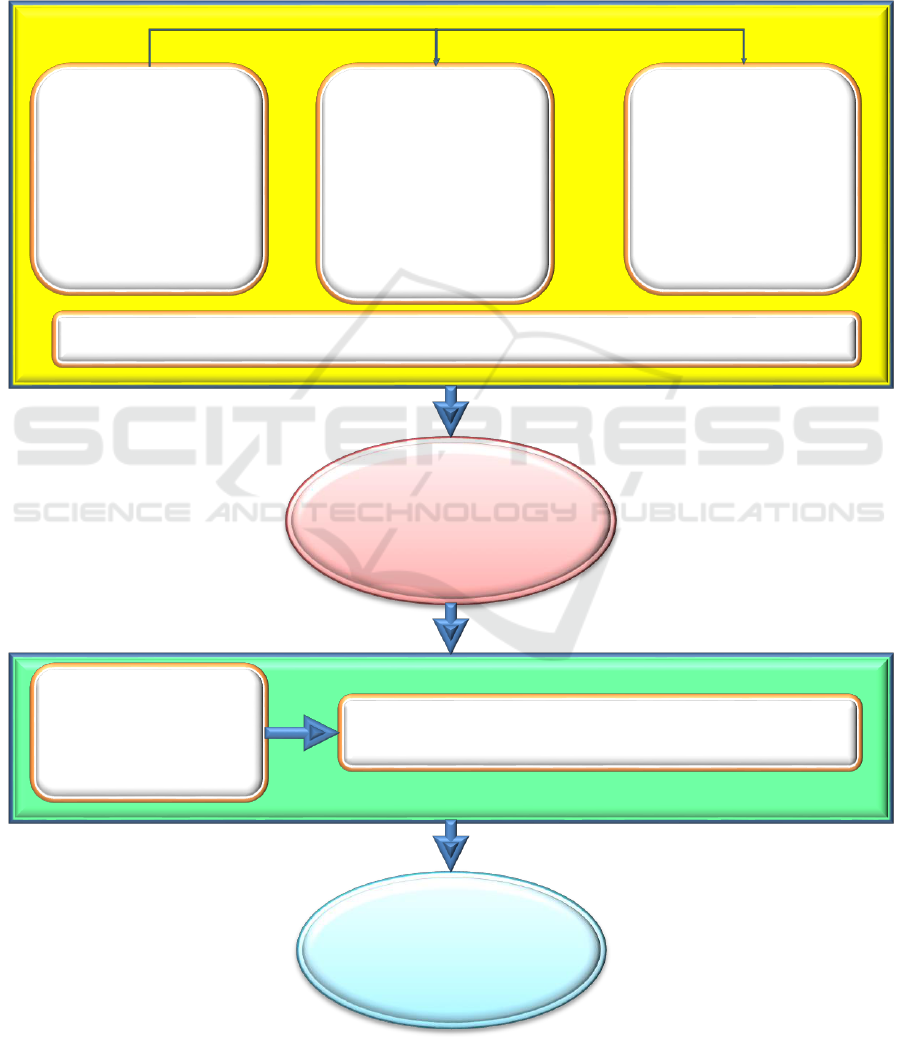

In brief, the research framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research framework.

Parents of children with

ASD who have

limitation in knowledge

and skills about ASD

intervention

Training for prarents of

children with ASD:

Concepts aboutf ASD,

Concepts about Social

skills, Concepts about

ASD intervention,

Concepts about

individualized

intervention program

Workshop for parents of

children with ASD:

•

Design the

Individualized

Intervention

Program

•

Practice the

intervention

techniques

STAGE I ACTIVITY: TRAINING AND WORKSHOP FOR PARENTS OF CHILDREN WITH ASD

Parents of children with

ASD who are able to give

intervention independently

Children with ASD who

have limitation in social

skills

STAGE 2 ACTIVITY: PARENTS INTERVENTION TO

CHILDREN

The social skills of

children with ASD

increase

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

220

3 METHODS

The study was carried out using a quasi-experimental

design. The use of this this design was: 1) test the

effectiveness of training to improve parents’

capability in designing individualized social skill

intervention program for their ASD children and 1) to

test the effectiveness of parental intervention to

improve their ASD children’s social skills.

The research subjects were 6 parents and their

ASD children. The parents were chosen as the

subjects based on the following criteria: 1) to have an

ASD child, 2) to be able to read and write, and 3) to

be willing to participate in the research. And the

children were chosen as the subjects based on the

following criteria: 1) to suffer from ASD with low

and moderate severity and 1) to be 5-7 years old.

The research instruments were: 1) parents’ self-

evaluation questionnaire on their capability in

designing the intervention program before and after

the training, 2) assessment sheets of the intervention

program contents prepared by the parents, and 3)

observation sheets used by the parents to assess their

children’s social skills after the parental intervention.

The children’s social skills assessment was carried

out every week during six weeks.

Data of parents’ capability in designing the

intervention program were analyzed quantitatively

using Wilcoxon Signed Rank with significance level

(α) of 0.05. The result of analysis of parents’ self-

evaluation data was used to figure out the

effectiveness of training in improving parents’

capability in designing the intervention program. The

assessment by the researchers used a 1-3 scoring

scale: 1 if the content of the program is not

appropriate, 2 if less appropriate, and 3 if appropriate.

Parents’ mean scores were grouped into three: “Not

Capable” if the mean score <1, “Quite Capable” if the

mean score = 1-1.49, and “Capable” if the mean score

= 1.5-2. The result of researchers’ assessment was

used to enrich the data of parents’ self-evaluation.

Data on children’s social skills after parental

intervention were analyzed qualitatively by seeing the

frequency of social skills consistently displayed by

the children per se every week. The assessment was

conducted for six weeks. The social skill display

frequency was divided into four, from the lowest to

the highest: “Almost Never” if the children almost

never displayed social skills trained by their parents,

“Occasionally” if they displayed them at times,

“Often” if they frequently displayed them in multiple

places or occasions to certain people, and “Almost

Always” if they consistently displayed them in

multiple places and occasions to many people. The

success of parental intervention to their children was

seen from the consistent frequency of social skills

displayed by the children.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Results

Based on parents’ self-evaluation result, the parents’

capability in designing the intervention program pre-

and post-training can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Mean score of parents’ capability in designing the

intervention program pre- and post-training.

PRE

POST

GAIN

2.86

6.57

3.71

Table 1 shows that parents’ capability in

designing the intervention program improved after

the training. Based on the non-parametric Wilcoxon

Signed Rank test using the significance level of 0.05

by means of SPSS version 20, the difference was

significant, 0.017 (p<0.05). Since p<0.05, so H0 was

rejected. In other words, the parents’ capability in

designing the intervention program improved

significantly after the training. Therefore, it can be

said that the training was proven to be effectively

improve parents’ capability in designing intervention

program for their ASD children.

Table 2 presents the researchers’ assessment score

of the content of the intervention program.

Table 2: Mean score of parents’ capability in designing

intervention program based on researchers’ assessment.

Subject

Mean

Score

Category

of

Capability

1.

1.97

Capable

2.

2

Capable

3.

1.71

Capable

4.

2

Capable

5.

1.66

Capable

6.

1.8

Capable

Table 2 shows that all parents were capable of

designing the intervention program appropriately.

Assessment of the effectiveness of parental

intervention is based on a parents’ weekly assessment

after the children received the intervention. The

intervention data were obtained after the parents gave

Becoming Autonomous Parents in Giving Intervention to Children with Autism - Is It Possible?

221

interventions at least within 6 weeks. The parents

recorded the consistent frequency of social skills

displayed by their children by providing qualitative

assessment: Almost Never, Occasionally, Often, and

Almost Always. Table 3 shows that all children, on

every aspect of social skills, displayed improved

frequency of social skills despite that the

improvement took place in different weeks.

Table 3: Consistent frequency of social skills displayed by the children.

SUBJECT

SOCIAL SKILL ASPECTS

WEEK

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1

Conversational skills

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

OF

-

Play skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Understanding emotion

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Dealing with conflict

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Friendship skills

AN

AN

AN

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

2

Conversational skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

-

Play skills

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

OC

-

Understanding emotion

OC

OC

OF

OF

AA

AA

AA

-

Dealing with conflict

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

-

Friendship skills

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

-

3

Conversational skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Play skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Understanding emotion

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

-

Dealing with conflict

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

-

Friendship skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

-

4

Conversational skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

AA

Play skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

-

Understanding emotion

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Dealing with conflict

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

Friendship skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

5

Conversational skills

OC

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

OF

-

Play skills

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

OF

OF

-

Understanding emotion

AN

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

OC

-

Dealing with conflict

AN

AN

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

-

Friendship skills

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

AN

-

6

Conversational skills

AN

AN

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

-

Play skills

AN

AN

AN

OC

AN

AN

OC

-

Understanding emotion

AN

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

OC

-

Dealing with conflict

AN

AN

AN

AN

OC

OC

OC

-

Friendship skills

AN

AN

AN

OC

AN

OC

OC

-

Note:

AN = Child almost never shows social skills behavior

OC = Child occasionally shows social skills behavior

OF = Child often shows social skills behavior

AA = Child almost always shows social skills behavior

Week-0 = social skills before intervention

Week-1 etc. = social skills after intervention

4.2 Discussion

Based on Table 4.1 and 4.2, it could be said that the

training effectively improve the parents’ capability in

designing the intervention program in accordance

with the needs and condition of their respective child

and family. The parents were trained to design the

individualized social skill intervention program by

taking into account the factual condition and needs of

their children and family. The parents also received

feedbacks about their prepared intervention program

and were given opportunity to propose improvements

to the program format so as to make it appropriate and

easy to do. According to Kolb (2007), an effective

training has several characteristics; among others are:

to begin with assessment of parents’ needs about

training, parents are given opportunity to practice

what they learn from training in a natural family

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

222

setting, parents get regular feedback from the trainer

during the exercise, and parents are given opportunity

to develop the skills acquired during the training.

Referring to these characteristics, the training could

be said effective to improve parents’ capability in

designing the individualized social skill intervention

program. It was understandable that the parents found

some difficulties at the early stage since they were not

used to designing an intervention program for their

own children. This is in line with the result of Shie

and Wang’s (2007) research that in parent

empowerment training, the professional therapists are

usually dominant in designing and developing an

intervention program, and the parents act as passive

information receivers.

Based on Table 4.3, it could be concluded that

overall the parental intervention improved social

skills of the children with both low and moderate

ASD, and the improvement occurred in different

periods among them. The result of this research is in

agreement with that of Dunst, Bruder, and Espe-

Sherwindt’s (2014) research that parent participation

in an intervention is a very important component in

enhancing children’s learning and development. In

addition, this research also confirms the statement of

Nefdt et al. (2010) that a natural intervention

procedure is easy to be understood by the parents. A

natural intervention procedure is an intervention

procedure designed in such a way that it is relevant to

family habits and values, done in an environment that

the parents and children are familiar with, and using

daily media and activities.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study has concluded that generally the

independent intervention program has successfully

empowered parents in providing intervention to their

children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

Elaborately, this study has concluded the followings:

First, the independent intervention program was

effective in improving parents’ understanding about

ASD, social skills, intervention, and individualized

social skills intervention program for children with

ASD.

Second, independent intervention training and

workshop program was effective in improving the

affective function of parents of children with ASD.

Third, independent intervention workshop

program was effective in improving parents’ skills in

designing individualized social skills intervention

program for their children diagnosed with ASD.

Fourth, generally the parents were quite

independent in designing the individualized social

skills intervention program for children with ASD.

Fifth, generally the training and workshop

improved the parents’ skills in implementing the

social skill intervention for their children diagnosed

with ASD.

Sixth, the parental intervention with reference to

the individualized social skills intervention program

developed by the parents was effective in improving

the social skills of children with ASD.

REFERENCES

Autism Ontario. 2012. What to look for when choosing

social skills programs for people with ASD. Social

matters: Improving social skills intervention for

Ontarians with ASD, no 42, September 2012. Retrieved

from:

www.autismontario.com/Client/ASO/AO.nsf/object/S

ocialMatters/$file/Social+Matters.pdf.

Beaudoin, A. J., Sébire, G., Couture, M. 2014. Parent

training interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum

disorder. Autism Research and Treatment, vol, 2014.

Article ID 839890, 15 pages, 2014.

doi:10.1155/2014/839890

De Bruin, E. I., Blom, R., Smit, F. M., van Steensel, F. J.,

Bögels, S. M. 2014. MY mind: Mindfulness Training

for Youngsters with Autism Spectrum Disorders and

Their Parents. Autism: The International Journal of

Research and Practice, 19, 906-914

Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Espe-Sherwindt, M. 2014.

Family capacity-building in early childhood

intervention: Do context and setting matter? School

Community Journal, 2014, 241, 37-48.

Elder, J. 2013. Empowering Families in the Treatment of

Autism. Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum

Disorder, vol.1.

Howell E, Lauderdale-Littin S., Blacher J. 2015. Family

impact of children with Autism and Asperger

Syndrome: A case for attention and intervention. Austin

J Autism and Relat Disabil. 2015; 12: 1008

Iversen et al. 2003. Creating a Family-Centerd Approach to

early intervention services: perceptions of parents and

professionals. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2003

Spring, 151, 23-31.

Jarbrink, K. et al. 2007. Cost-impact of young adults with

high-functioning autistic spectrum disorder, in

Research in Developmental Disabilities, 2007 Jan-Feb,

281, 94-104.

Kim, Y.S, et al. 2011. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum

Disorder in a Total Population Sample, dalam

American Journal of Psychiatry, 168 9, 904-12.

Knowles, M.S., Holton, E.F., Swanson, R.A. 2005. The

adult learner: The definitive classic in education and

human resource development, 6th ed. California, USA:

Elsevier, Inc.

Becoming Autonomous Parents in Giving Intervention to Children with Autism - Is It Possible?

223

McConachie, H., Diggle, T. 2007. Parent Implemented

Early Intervention for young children with Autism

Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review. Journal of

Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13, 120–129.

Media Indonesia Epaper 2014. Terapi Autisme Masuk

Tanggungan JKN, dalam JAMSOS.com INDONESIA

edisi 3 April 2014. Retrieved from:

http://www.jamsosindonesia.com/cetak/print_externall

ink/7939/ 24 November 2014

Negri, L.M., Castorina, L.L. 2014. Family Adaptation to a

Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dalam

Tarbox, et al. Editors. Handbook of early intervention

for Autism Spectrum Disorders: Research, Policy, and

Practice. Hlm. 149-174. New York: Springer Science

Business Media.

Özdemir, S. 2007. A paradigm shift in early intervention

services: from child-centeredness to family

centeredness. Ankara Universities Dil ve Tarih-

Coğrafya Fakültesi Dergisi, 2007, 472, 13-25.

Poling, A., Edwards, T.L. 2014. Ethical Issues in Early

Intervention. Dalam Tarbox, J., Dixon, D.R., and

Sturmey, P. Editors. Handbook of early intervention for

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Research, policy, and

practice. pp. 177-206. New York: Springer Science

Business Media.

Relate to Autism. 2010. Why Add Parent-implemented

Component to Autism Treatment Programs?. Retrieved

from:

http://www.google.co.id/url?sa=tandrct=jandq=andesr

c=sandsource=webandcd=14andved=0CC8QFjADOA

oandurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.autism-

community.com%2Fwp-

content%2Fuploads%2F2010%2F11%2FParent-

Implemented-

Programs.pdfandei=h3oqVJm7GpDluQTxgoK4DAan

dusg=AFQjCNF21VvyC_ugWwlDsUCXcOJebyU78

wandbvm=bv.76477589,d.c2E 30 September 2014

Rudy, L.J. 2013. Should parents provide their own

children’s autism therapy?. Retrieved from:

http://autism.about.com/od/treatmentoptions/p/Should-

Parents-Provide-Their-Own-Childrens-Autism-

Therapy.htm 11 November 2014

Salomone, E., et al. 2016. Use of early intervention for

young children with autism spectrum disorder across

Europe. Autism. 2016, 202, 233-249.

Shie, J., Wang, T. 2007. Using Parent Empowerment in

Parenting Program for a Young Child with Autism.

Department of Special Education, the National Taiwan

Normal University. Retrieved from:

http://www.google.com/url?sa=tandrct=jandq=andesrc

=sandsource=webandcd=13andved=0CDcQFjACOAo

andurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ntnu.edu.tw%2Facad

%2Frep%2Fr97%2Fa5%2Fa501-

1.docandei=Tyg3VI3qN5KSuASEhYD4DQandusg=A

FQjCNHC_M4h1oYh7an04HV28JYvCwNsdA 10

October 2014

Stone, W., DiGeromino, T.F. 2014. Does my child have

Autism?, dalam 100 Day Kit, For Newly Diagnosed

Families of Young Children. Autism Speaks, Inc.

Tomaino, M.E., Miltenberger, C.A., Charlop, M.H. 2014.

Social skills and play in children with autism. Dalam

Tarbox, J., Dixon, D.R., and Sturmey, P. Editors.

Handbook of early intervention for Autism Spectrum

Disorder: Research, policy, and practice. pp. 437-452.

Wang, L. et al. 2013. Healthcare Service Use and Costs for

Autism Spectrum Disorder, A Comparison between

Medicaid and Private Insurance, dalam Journal of

Autism Developmental Disorder, 2013, 43:1057–1064.

ICES 2017 - 1st International Conference on Educational Sciences

224