Motivation in Physical Education among Filipino High School

Students

James V. Bailon, Erwin M. Blancaflor, Ma. Joannes Kevin B. Datu-Puda, Karen Jade Dabu, Romeo

R. Rioflorido, and Jonathan Cagas

Philippine Normal University

University of the Philippines Diliman

vergara.la@pnu.edu.ph

Keywords: Autonomy Support, Gender Differences, Motivation, Physical Education.

Abstract: Motivating students to participate actively in physical education (PE) is often major concern for physical

education teachers. As physical ability, interest levels, and effortful investment of students within PE classes

can vary among students, understanding the motivational issues in this setting is particularly interesting to

researchers and practitioners alike. One line of research has examined the antecedents of three broad teacher

behaviors, namely provision of autonomy support, structure (i.e. clear expectations and guidelines), and

involvement (i.e. personal interest in students (Ntoumanis, & Standage, 2009). Therefore, the objectives of

this study are: (1) to test the hypothesis that perceived autonomy support from teachers influences students’

motivation in PE, and (2) to examine gender differences in the perceived autonomy support from the teachers.

Two hundred seventy nine (n = 279) students from two public high schools participated. Results of Pearson

R indicated that perceived autonomy support from teacher affects students’ intrinsic motivation, and identified

regulation. In terms of gender differences, results showed that they are no significant differences in the

Perceived Autonomy Support in Physical Education. Overall, results suggest that providing autonomy

supportive learning environment in PE is beneficial in terms of developing more autonomous forms of

motivation in students.

1 INTRODUCTION

Motivating students to participate actively in physical

education (PE) is often major concern for physical

education teachers. The physical ability, interest

levels, and effortful of students within PE classes can

be different among students, understanding the

motivational issues in this setting is particularly

interesting to researchers and practitioners in the field

of teaching. Teachers’ interpersonal style has been

shown to influence students’ motivation in PE

(Reeve, Jang, Carrell, & Barch, 2004). Physical

Education (PE) is significant setting where youth are

taught about lifelong physical activities (Bocarro,

Kanters, Casper, & Forrester, 2008) and it has the

potential to provide children and adolescents with

opportunities to meet the recommended amount of

health-enhancing physical activity to promote

students participation in PE (Trudeau & Sheppard,

2008). With physical inactivity among school

children becoming a health concern worldwide based

on the research of Guthold, Cowan, Autenrieth, Kann,

& Riley, 2010. According to Barkoukis, Hagger,

Lambropoulos, and Tsorbatzoudis (2010),

understanding how to enhance young people’s

motivation in PE is an important research area.

Research suggests that students who are motivated in

PE are most likely to feel motivated in becoming

physically active during their leisure-time as well.

The study aims to examine how a teacher’s

motivational style can affect students’ motivation in

physical education classes. Specifically, it had the

following statement of purposes:

1. to determine how the perceived autonomy

support of teachers is related to high school

student’s motivation in PE;

2. to test if there is a difference in the perceived

autonomy support based on students’ gender.

1.1 Motivation in Physical Education

According to Ryan and Deci (2002), Self-

determination theory proposes that there are three

basic psychological needs which are essential

364

Bailon, J., Blancaflor, E., Datu-Puda, M., Dabu, K., Rioflorido, R. and Cagas, J.

Motivation in Physical Education among Filipino High School Students.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sports Science, Health and Physical Education (ICSSHPE 2017) - Volume 1, pages 364-369

ISBN: 978-989-758-317-9

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

rudiments for optimal motivation and well-being.

These psychological needs are the need for

competence (belief in one’s ability to perform a

certain task efficiently and effectively), relatedness

(feeling of belongingness or being connected with

others), and autonomy (perception of being the

initiator and source of one’s behavior). Fulfillment of

experiencing these psychological needs can lead to

cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes in PE

(Ntoumanis & Standage, 2009). The research of Ryan

and Deci (2000) says that the failure to address these

needs may lead to decreased motivation and

experience of ill-being or boredom. One way in which

these needs are fulfilled is when the PE teacher

creates an autonomy-supportive learning

environment that proves by the research of Bryan and

Solmon, (2007), and it also promotes self-

development, and exhibits compassion and

consideration towards the students. Specifically, says

that needs fulfillment plays a mediating role in the

relationship between perceived teacher autonomy-

support and students’ self-determined motivation as

agreed on the research of Barkoukis, Hagger,

Lambropoulos, & Tsorbatzoudis, (2010) and

subjective vitality resulted on the research of Taylor

and Lonsdale, (2010). Various studies have examined

the effects of needs fulfillment on students’

motivation and other essential outcomes in PE. One

of the studies from Barkoukis, Hagger,

Lambropoulos, & Tsorbatzoudis (2010) tested the

role of needs fulfillment in the formation of self-

determined motivation in PE and leisure time

contexts.

1.2 Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

and Learning

Intrinsic motivation refers to behaviors done in the

absence of external impetus that are inherently

interesting and enjoyable which is according to the

research of Ryan and Deci (2000a). Based on

deCharms (1968), when people are intrinsically

motivated they play, explore, and engage in activities

for the inherent fun, challenge, and excitement of

doing so. Such behaviors have an internal perceived

locus of causality. Proven to the research of Deci and

Ryan, 1985, they are experienced as emanating from

the self rather than from external sources, and are

accompanied by feelings of curiosity and interest.

To support the definition of Extrinsic motivation,

according to the research of Ryan and Deci (2000a),

refers to behaviors performed to obtain some outcome

separable from the activity itself. SDT specifies four

distinctive types of extrinsic motivation that vary in

the degree to which they are experienced as

autonomous and that are differentially associated

with classroom practices (e.g. autonomy supportive

versus controlling instruction) and learning outcomes

(e.g. conceptual learning versus rote memorization)

The least autonomous type of extrinsic motivation is

external regulation, whereby behaviors are enacted to

obtain a reward or to avoid a punishment. It was

proven from the research of Vansteenkiste, Ryan, and

Deci (2008), that such behaviors are poorly

maintained once the controlling contingencies (e.g.

grades) have been removed. The next type of extrinsic

motivation is introjected regulation, whereby

behaviors are enacted to satisfy internal

contingencies, such as self-aggrandizement or the

avoidance of self-derogation. It is say in the research

of Nicholls (1984) and Ryan (1982) with introjected

regulation, the student who studied to perform well

on the exam now studies to feel pride or to avoid

feeling guilty for not having studied enough. One

particular type of introjected regulation is ego

involvement, which refers to one’s self-esteem being

contingent on one’s performance. When ego is

involved, a student feels internal pressure to learn so

as to avoid shame or to feel worthy (Niemiec, Ryan,

& Brown, 2008). The most autonomous type of

extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation, whereby

those identified regulations have been produced with

other aspects of the self.

1.3 Self Determination Theory

Based on the research of Deci and Ryan (2000),

Niemiec, Ryan, and Deci (2010), and Ryan and Deci

(2000b), Self Determination Theory is a macro-

theory of human motivation, emotion, and

development that takes interest in factors that either

facilitate or forestall the assimilative and growth-

oriented processes in people.

One of the principles of SDT is that there are three

basic psychological needs namely, universal across

cultures, gender, and developmental stage. According

to Deci & Ryan, 2000, the basic needs are vital for

continuous psychological growth, integrity, and well-

being. Based on the studies of Taylor and Lonsdale

(2010) to observe SDT’s universality hypotheses in

the PE context, the study compared the relationships

between perceived autonomy support, needs

fulfillment, and subjective vitality in individualistic

(UK) and collectivistic (Hong Kong, China) cultures.

Motivation in Physical Education among Filipino High School Students

365

1.4 The Basic Psychological Needs in

Physical Education Scale

In the year 2011, Vlachopoulos, Katarzi and Kontou

research about the Basic Psychological Needs in

Physical Education Scale (BPNPE) Scale; where it is

defined as a short context-specific instrument

designed to measure fulfillment of students’ basic

psychological needs in PE. The said instrument was

anchored to SDT and has only been validated

recently. The instrument has been translated to

German (Heckmann, 2013) and Filipino (Cagas &

Hassandra, 2014) which the researcher has used for

the studies.

1.5 Perceived Autonomy Support of

Teachers

In the field of teaching the practices does not come in

empty. Based on the research of (Ryan & Brown,

2005) one major reason teachers use controlling,

rather than autonomy-supportive, strategies in the

classroom is that external pressures are placed on

them, and this idea has been supported in a growing

number of studies in accordance with SDT. Same as

with the study of Pelletier Séguin-Lévesque &

Legault. (2002) they examined 1st to 12th grade

Canadian teachers and have observed that the more

teachers perceive pressure from above (e.g. having to

comply with an imposed curriculum, pressure toward

performance standards), the less autonomous they are

toward teaching, which in turn was connected with

teachers being more controlling with students.

2 METHOD

Participant were 279 students (105 boys, 174 girls)

from two public high schools. They completed a two-

page questionnaire assessing their perceived levels of

needs fulfillment, autonomy support, and vitality.

Ages ranged from 11 to 19 years. Participants also

indicated their primary spoken language. Three

hundred fifty one answered only one primary

language, 351 of which speaks Filipino (91.88%),

3 MEASURES

Perceived Autonomy Support. Students’ perceptions

of the level of autonomy support provided by their

teacher in physical education classes were measured

using the 15-item; e.g., “I feel that my PE teacher

provides me choices and options”) translated in

Filipino which is Learning Climate Questionnaire

(LCQ; Williams & Deci, 1996).

The Motivation was measured using the

Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC; Goudas,

Biddle, & Fox, 1994) was employed to assess four

types of behavioral regulation in the physical

education context. All items were rated on a 7-point

Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree)

to 7 (strongly agree).

4 PROCEDURE

The data gathering of the researchers was first to get

permit to collect data from the principal of the two

public schools. Then questionnaire were administered

to the participants and data was collected during their

free time. The purpose of the research was explained

to the participants before the questionnaires were

administered. Consent form was also given to the

students that their participation is voluntarily. The

participants were also told that their answers would

not affect their grades, remain confidential unless

requested by the participants and their principal, and

be accessible only to the researchers.

5 DATA ANALYSIS

The statistical analysis that was used to get the

correlational of the types of motivation to perceived

autonomy support of teachers is through Pearson R.

Same as with the students’ gender difference in terms

of motivation in physical education and independent

t-test sample was also used.

6 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section presents the correlational results

between the types of motivation and perceived

autonomy support of teachers. This shows also

difference in motivation based on student’s gender.

ICSSHPE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sports Science, Health and Physical Education

366

6.1 Perceived Autonomy Support of

Teachers and Students’ Motivation

in Physical Education

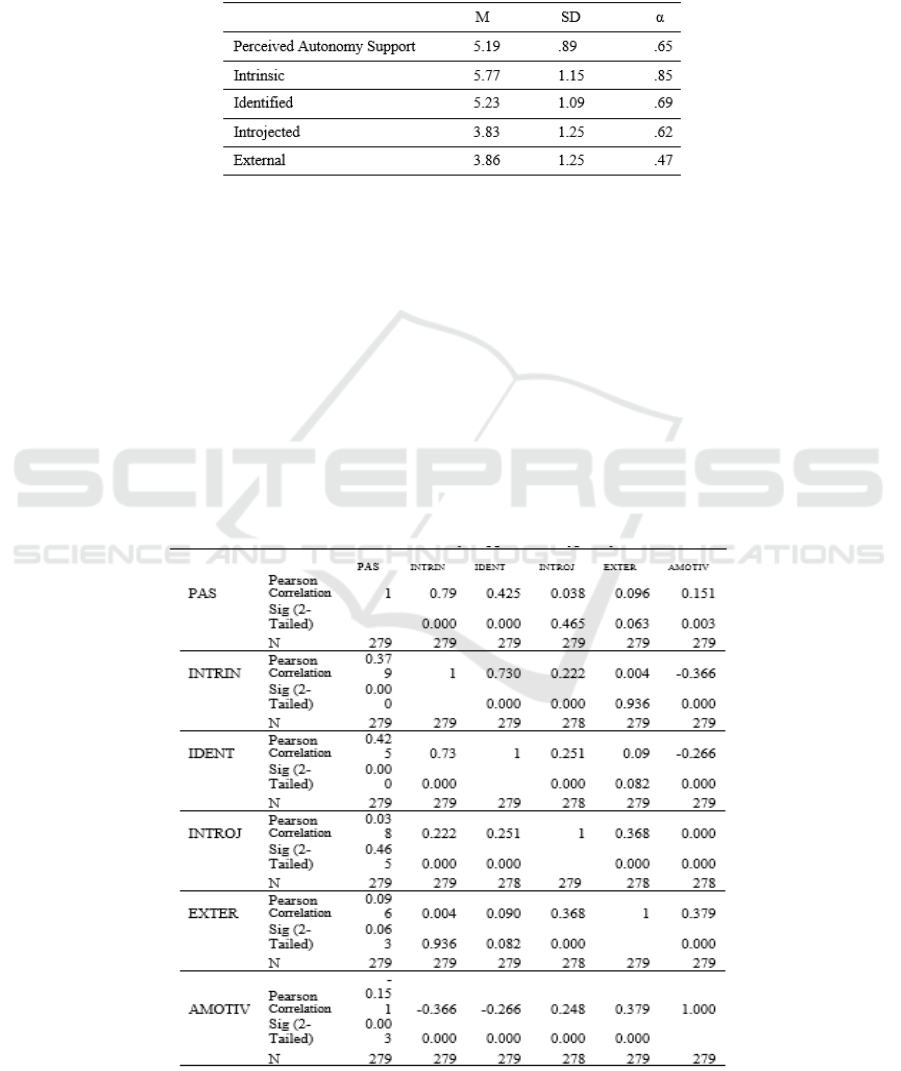

Table 1: Mean Score And Response on The Perceived Autonomy Support And Types of Motivation.

In table 1, it presents the result of the response of

students for the Perceived Autonomy Support (PAS)

and the types of motivation in Physical Education.

The Perceived Autonomy Support in general got a

mean score of 5.19 with a standard deviation of 0.89,

means that the students feel that the teachers are

supportive in teaching Physical Education. Then, the

first type of motivation is Intrinsic Motivation which

got a mean score of 5.77 with a standard deviation of

1.15 these means that the students wants to learn PE

because it’s enjoyable and fun, while the second type

of motivation which is Identified Regulation got a

mean score of 5.23 with a standard deviation of 1.09

it means that it is a need for them to learn Physical

Education because it will not only develop their

physical aspects but holistically. The other types of

motivation which are Introjected Regulation got a

mean score of 3.83, External Regulation got a mean

score of 3.86 and Amotivation got a mean score of

2.68. Those three types got a low mean score and it

means that students don’t use ego involvement for the

Introjected, rewards and punishment are not their

motivation in Physical Education for the External

Regulation.

Tabel 2: Correlations between Perceived Autonomy Support Types of Motivation.

Motivation in Physical Education among Filipino High School Students

367

Table 2 shows the result for the correlation

between Perceived Autonomy Support and Types of

Motivation (Intrinsic, Identified Regulation,

Introjected Regulation, External Regulation). It

shows that Perceived Autonomy Support is highly

related to Intrinsic with Pearson R value of 0.79,

p>0.05 and Identified regulation with Pearson r value

of 0.425, p>0.05 which means students have

motivation in PE when teacher makes the class fun

and enjoyable at the same time explained the

importance of PE in their lives. There is a High

Perceived Autonomy Support and Low Introjected

regulation (Pearson r value of 0.038, p<0.05) External

Regulation (Pearson r value of -0.096, p<0.05) which

means the motivation of students in PE is not because

of rewards and punishment.

Figure 1: Correlational Between PAS and Types of

Motivation Based on Students’ Gender.

Based on the figure above the results shows the

correlation of PAS and Types of Motivation based on

gender. The Perceived Autonomy Support with the

Pearson r value of 0.38, p<0.001 for Intrinsic

Motivation, 0.43, p<0.001 shows that the students

have motivation in PE based on their perception that

it’s fun and learning experience and at the same it’s

important for them to learn PE in their daily life which

promotes lifelong fitness while Amotivaton for -0.15,

p>0.001 means that the students are motivated in PE.

6.1.1 Gender Difference in Perceived

Autonomy Support

Based on Table 3 it shows the result of gender

differences on perceived autonomy support. The male

got a mean score of 5.30 while the female 5.25 it

means both are motivated in PE because of the

teachers support and style in teaching PE. Based on

the mean difference of 0.4947 it means that there is

no significant difference in the motivation in PE

based on gender.

Table 3: Group Statisties.

Gender N M SD df Sig.

Mean

Difference

PAS Male 105 5.3 0.861 277 0.662 0.494

Female 174 5.25 0.943

7 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Physical Education plays an important

role in promoting positive attitudes towards lifelong

physical activity. Our study concludes that Filipino

P.E teachers may use autonomy support strategies to

enhance students’ motivation in PE. It is also

concluded that students’ perception to autonomy

support based on gender signifies the important role

of teachers in PE and the students’ motivation in

promoting lifelong fitness.

REFERENCES

Barkoukis, V., Hagger, M. S., Lambropoulos, G.,

Tsorbatzoudis, H. 2010. Extending the trans-contextual

model in physical education and leisure-time contexts:

Examining the role of basic psychological needs

satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Psychology,

80, 647-670.

Bocarro, J., Kanter, M., Casper, J., Forrester, S. 2008.

School Physical Education, Extracurricular Sports, and

Lifelong Active Living. Journal of Teaching in Physical

Education, 27, 155-166.

Bryan, C. L., Solmon, M. A. 2007. Self-determination in

physical education: Designing class environments to

promote active lifestyles. Journal of Teaching in

Physical Education, 26, 260- 278.

deCharms, R. 1968. Personal Causation. New York:

Academic Press

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and

Self-determination inHuman Behavior. New York:

Plenum.

Deci, E.L. and Ryan, R.M. 2000. The “what” and “why” of

goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination

of behavior, Psychological Inquiry 11:227–68.

ICSSHPE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Sports Science, Health and Physical Education

368

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. 2002. The paradox of

achievement: The harder you push, the worse it gets, in

J. Aronson (ed.), Improving Academic Achievement:

Contributions of Social Psychology, pp. 59–85. New

York: Academic Press.

Flavell, J. H. 1999. Cognitive development: Children’s

knowledge about the mind, in J.T. Spence (ed.), Annual

Review of Psychology, Vol. 50, pp. 21–45. Palo Alto,

CA: Annual Reviews, Inc.

Gagne, M. 2003. The role of autonomy support and

autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior

engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 199–223.

Gagne, M., Ryan, R. M., Bargmann, K. 2003. Autonomy

support and need satisfaction in the motivation and well-

being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport

Psychology, 15, 372–390.

Goudas, M., Biddle, S., Fox, K. 1994. Perceived locus of

causality, goal orientations and perceived competence in

school physical education classes. The British Journal

of Educational Psychology, 64, 453–463. PubMed.

Guthold, R., Cowan, M. J., Autenrieth, C. S., Kann, L.,

Riley, L. M. 2010. Physical activity and sedentary

behavior among schoolchildren: A 34-country

comparison. The Journal of Pediatrics, 157, 43-49.

Nicholls, J.G. 1984. Achievement motivation: Conceptions

of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and

performance, Psychological Review 91: 328–46.

Niemiec, C.P., Ryan, R.M., Brown, K.W. 2008. The role of

awareness and autonomy in quieting the ego: A self-

determination theory perspective, in H.A.

Niemiec, C.P., Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. 2010. Self-

determination theory and the relation of autonomy to

self-regulatory processes and personality development’,

in R. H. Hoyle (ed.), Handbook of Personality and Self-

regulation. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Ntoumanis, N., Standage, M. 2009. Motivation in physical

education classes: A self-determination perspective.

Theory and Research in Education, 7, 194-202.

Pelletier, L.G., Séguin-Lévesque, C. and Legault, L. 2002.

Pressure from above and pressure from below as

determinants of teachers’ motivation and teaching

behaviors’, Journal of Educational Psychology 94: 186–

196.

Ryan, R.M. and Brown, K.W. 2005. Legislating

competence: High-stakes testing policies and their

relations with psychological theories and research, in

A.J. Elliot and C.S. Dweck (eds), Handbook of

Competence and Motivation, pp. 354–72. New York:

Guilford Publications.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. 2002. Overview of self-

determination theory: An organismic dialectical

perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.),

Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3-33).

Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. 2000. Self-determination theory

and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social

development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist,

55(1), 68-78.

Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. 2000a. Intrinsic and extrinsic

motivations: Classic definitions and new directions,

Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 54–67.

Ryan, R.M. 1982. Control and information in the

intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive

evaluation theory, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology 43: 450–61.

Ryan, R.M., Connell, J.P. 1989. Perceived locus of

causality and internalization: Examining reasons for

acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 57, 749–761. PubMed.

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Hardre, P. and Omura, M. 2002.

Providing a rationale in an autonomy-supportive way as

a strategy to motivate others during an uninteresting

activity, Motivation and Emotion 26: 183–207.

Taylor, I. M., Lonsdale, C. 2010. Cultural differences in the

relationships among autonomy support, psychological

need satisfaction, subjective vitality, and effort in

British and Chinese physical education. Journal of Sport

& Exercise Psychology, 32, 655-673.

Trudeau, F., Sheppard, R. J. 2008. Physical education,

school physical activity, school sports, and academic

performance. International Journal of Behavioral

Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5(10).

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L. 2008. Self-

determination theory and the explanatory role of

psychological needs in human well-being, in L. Bruni,

F. Comin and M. Pugno (eds), Capabilities and

Happiness, pp. 187-223. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Vlachopoulos, S. P. 2012. The role of self-determination

theory variables in predicting middle school students’

subjective vitality in physical education. Hellenic

Journal of Psychology, 9, 179-204.

Williams, G., Deci, E. 1996. Internalization of

biopsychological values by medical students: A test of

selfdetermination theory. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 70, 767–779. PubMed.

Motivation in Physical Education among Filipino High School Students

369