Teachers’ and Students’ Judgment of Grammaticality of Sentences

Clara Herlina Karjo

English Language Department, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia

clara2666@binus.ac.id, claraherlina@yahoo.com

Keywords: Grammaticality judgment test, grammatical, ungrammatical, construction.

Abstract: Understanding a language includes the ability to assess whether a construction in that language is grammatical

or ungrammatical. To determine whether a construction is well-formed, a standard grammaticality judgment

test can be used. In such test, participants make an intuitive judgment on the accuracy of form and structure

in individual decontextualized sentences. This study involved 20 students and 20 teachers of English in Bina

Nusantara University who were instructed to rate the grammaticality of twenty individual sentences. To

justify their decision, the participants were also instructed to correct the ungrammatical sentences. The degree

of dissimilarity of answers was evaluated by looking at internal linguistic criteria and usage of such

construction. The results varied from unanimous decision on ungrammaticality for sentence like She aren’t

care for me, and a divided response on others, such as Which man did Bill go to Rome to visit? However,

teachers tend to decide more sentences as ungrammatical, while the students considered more sentences as

grammatical.

1 INTRODUCTION

What is a grammatical sentence? Fromkin, Rodman,

Hyams (2017) say that a sentence is grammatical

when it conforms to the rules of both grammars;

conversely, an ungrammatical sentence deviates in

some way from these rules. Both grammars, in their

sense, are the mental grammar that speakers have in

their mind and descriptive grammar, which is the

linguists’ description of the grammar and the

language itself.

In the field of second language acquisition, these

two kinds of grammar are termed as implicit and

explicit knowledge (Ellis, 2009). Implicit knowledge

is unconscious knowledge that speakers are not aware

of possessing, while explicit knowledge is conscious

knowledge that speakers are aware of possessing,

although they might still not be able to verbalize it

(Rebuschat & Williams, 2012). Therefore, sometimes

people can be very confident when deciding the

grammaticality of a sentence but they cannot explain

why Dienes & Scott (2005).

To illustrate, let’s see the following sentences:

1. Colorless green ideas sleep furiously

2. Furiously sleep ideas green colorless.

Sentence (1) though illogical, is grammatical,

while sentence (2) is ungrammatical. The first

sentence is considered as grammatical because it

follows the syntactic rule of an English sentence that

a sentence should consist of an NP as subject and a

VP as predicate. Thus, the sentence can be analysed

as:

NP (colorless green ideas) + VP (sleep furiously).

Conversely, the second sentence violates the

prescriptive syntactic rule of a good sentence since it

begins with a VP (furiously sleep). However, the first

sentence, although it is grammatical, is unacceptable

because it is semantically anomalous. Anomaly is the

phenomenon that a sentence, though grammatical is

meaningless because there is an incompatibility in the

meaning of the words. Several semantic anomalies

are found in this sentence. The NP colorless green

ideas is unacceptable because ideas is an abstract

word that does not have color. Moreover, colorless

and green are also contradictory, because something

cannot be green as well as colorless at the same time.

Besides being semantically anomalous, there are

other reasons for speakers to reject perfectly

grammatical sentences. Dabrowska (2010) notes

several reasons such as violation of some prescriptive

notions (This is something I will not put up with) and

difficulty of processing (The horse raced past the

barn fell). On the contrary, a sentence could be

acceptable but ungrammatical (ex. Watched some TV,

then went to bed as an answer to the question What

did you do last night). The notion of grammaticality

and acceptability of a sentence is introduced by

Chomsky (1965) He posits that a grammatical

sentence is generated by the speaker’s grammar,

Karjo, C.

Teachers’ and Students’ Judgment of Grammaticality of Sentences.

DOI: 10.5220/0007161900530057

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 53-57

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

53

which is part of the language as delineated by his or

her competence. On the contrary, an acceptable

sentence is consciously accepted by a speaker as part

of his or her performance. Grammaticalness is only

one of the many factors that interact to determine

acceptability. Schütze, (1996) summarizes that

grammaticality judgment is a product of performance

and intuition is part of competence.

Researches on grammaticality judgment have

been extensively done in recent years. Rimmer (2006)

mentioned that a grammaticality judgment test (GJT)

is a standard method of determining whether a

construction is well-formed or not. (Tremblay, 2005)

claimed that GJT is one of the most widespread data

collection methods that linguists use to test their

theoretical claims. Yet, the use of GJTs has become

quite controversial (Riemer, 2009) because of the

absence of clear criteria to determine the exact nature

of grammaticality. Tabatabaei & Dehghani (2012)

also questioned the reliability of GJT as a means for

measuring learners’ linguistic competence (e.g.

knowledge about syntactic structures and rules).

Another issue is regarding the informants or subjects

of the study. Rimmer (2006) employed English

teachers in Russia which he termed as expert users.

Similarly, Dabrowska (2010) compared the linguists

and non-linguists’ judgment ability.

Following the previous studies, this study uses

GJT to measure the grammatical knowledge of the

participants. However, unlike the other studies, the

participants of this research are EFL university

students and teachers.

There are three research questions which are

discussed in this study:

1. To what extent do students and teachers

perceive the grammaticality of the sentences?

2. Which sentences are considered the most

ungrammatical by each group of participants?

3. What causes such different perception of

grammaticality?

2 METHODOLOGY

The subjects for this research were twenty lecturers

and twenty students from English Department Bina

Nusantara University. All of the lecturers have at least

master degree in English language or literature. While

the students ranged from semester five to eight.

Subjects were presented with a list of twenty

sentences. The instructions were to mark each

sentence as grammatically “correct” or “incorrect”

based on their intuition and knowledge. The

researcher also asked the subjects to give suggestions

of the “correct” or grammatical sentence for the

incorrect ones.

The results were processed by calculating a ratio

for each sentence between “correct” and “incorrect”

judgment and also by comparing the rank of

grammaticality judgment by students and teachers.

The twenty sentences are presented below:

1. Who did you quit college because you hated?

2. She aren’t care about me.

3. Either you or I are wrong

4. Which book would you recommend reading?

5. John angered while Susan amused the woman.

6. Who did John invite?

7. What did you bring that book to be read out

for to?

8. The plane that the pilot that the police

questioned flew crashed

9. John was bought the book

10. Bill sent London a package

11. John announced a plan to steal Bill’s car late

tomorrow.

12. The woman sitting next to the door’s shoes are

like mine.

13. You should lay down on the bed.

14. I wonder whether John can solve the problem

15. John teached me how tie my shoes.

16. I bought three mouses at the computer store

17. There’s only one person who thinks of

themself.

18. That is the sort of up with which will not put I.

19. Which man did Bill go to Rome to visit?

20. Susan trained like she’d never done before.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Teachers and students showed different perception

regarding the grammaticality of all the sentences.

However only one sentence that gained unanimous

opinion from all the participants, i.e. She aren’t care

about me (rejected by 100% of the subjects). The total

results are presented in Table 1 in which the raw

numbers of participants’ responses were converted

into percentages. The table only displays the

percentages of the participants’ responses who

considered the sentences as grammatical. Thus, for

sentence number 1, 15 % of the teachers considered

the sentence as grammatical, while none of the

students (0 %) considered it as “correct”. However,

the percentage obtained for each sentence does not

signify a degree of grammaticality, nor does it

indicate the correctness of their judgment. So, if a

student judged a sentence as grammatical while a

teacher judged the same sentence as ungrammatical,

that does not mean that the student made incorrect

judgment and the teacher made correct judgment.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

54

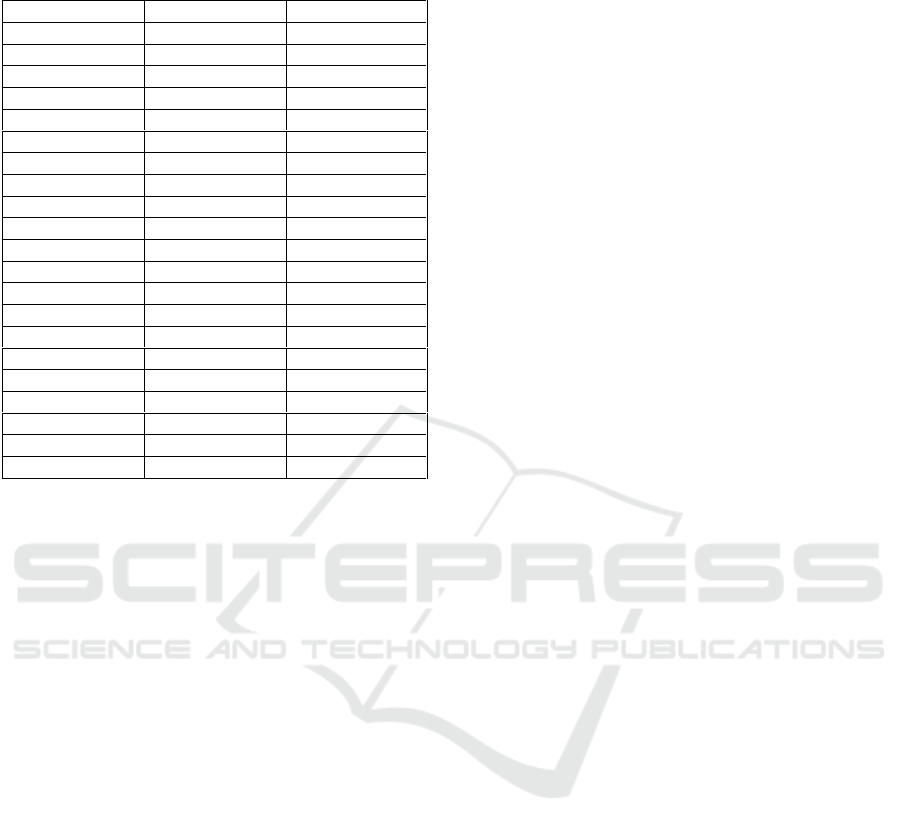

Table 1: Grammaticality judgment by teachers and

students.

Sentences

Teachers

Students

1

15 %

0 %

2

0%

0 %

3

45 %

35 %

4

50 %

30 %

5

30 %

60 %

6

70 %

65 %

7

10 %

45 %

8

20 %

10 %

9

15 %

45 %

10

20 %

35 %

11

50 %

50 %

12

15 %

30 %

13

90 %

95 %

14

60 %

80 %

15

0 %

30 %

16

35 %

80 %

17

20 %

65 %

18

15 %

10 %

19

40 %

35 %

20

60 %

75 %

Total

31.43%

44 %

The numbers shown in table 1 denote the

percentages of the number of teachers or students

who perceived that the sentences correct or

grammatical. Thus, for sentence number 2, for

example, none of the teachers or students thought that

the sentence is grammatical. They all agreed that

sentence number 2 She aren’t care about me is

ungrammatical. On the other hand, for sentence

number 5 John angered while Susan amused the

woman, as many as 30 % of the teachers agreed that

this sentence is grammatical; while 60 % of the

students thought that this sentence is grammatical. In

total, the teacher group judged only 31.43% sentences

are grammatical; on the contrary, the student group

judge 44 % of the sentences as grammatical. This

result shows that teachers can find more

grammaticality issues in the given sentences. These

findings can be similarized to Dabrowska (2010)

regarding the comparison of linguists’ and non-

linguists’ judgements of grammaticality. She found

that linguists’ judgments are sensitive to grammatical

structure and relatively insensitive to lexical content;

while non-linguists’ judgement show clear

interactions between lexical content and grammatical

structure. In summary, teachers, who can be

categorized as linguists, are more aware of

grammatical rules while the students focus more on

their intuition when judging the grammaticality of

sentences.

From Table 1, it can be seen that for the teachers,

the three most ungrammatical sentences are number

2, 15 and 7. The level of ungrammaticality for these

sentences is shown by the low percentage gained for

each sentence, i.e. 0%, 10 % and 0%. On the other

hand, the students chose sentences number 1, 2 and 8,

which gained 0 %, 0% and 10 %. Meanwhile, the

sentences which caused different judgment between

teachers and students are sentences number 16 and

17. Sentence number 16 was judged correct by 35%

of the teachers but 80% of the students judged it

correct. Similarly, sentence number 17 was judged

correct by 20 % of the teacher but it was judged

correct by 65 % of the students. The discussion for

the grammaticality or ungrammaticality of these

sentences is outlined below.

Sentence 1 : Who did you quit college because you

hated? (15 % of teachers and 0% of students judged

correct). The pronoun ‘who’ is used to ask questions

about a person’s identity. ‘Who’ can be the subject or

object of a verb, but ‘whom’ is sometimes used in

formal English instead of ‘who’ as the object of verb

(Cobuild, 1992:200). While the use of pronoun ‘who’

should not be problematic, the adverbial clause

because you hated present processing problem. The

clause because you hated should not be included in

the question because as (Biber, et al. ( 2000) said,

questions are typically expressed by full independent

clauses in the written register. Thus, questions

consisting of two different clauses are uncommon.

Moreover, there is a semantic anomaly in the first part

of the sentence. The question word ‘who’ does not

collocate with the verb ‘quit college’. ‘Who’ is

supposed to relate to the second part ‘Who did you

hate?”

Sentence 2: She aren’t care about me. (0 % of

teachers and students judged correct). This sentence

is unanimously judged as incorrect by all participants

because of the violation of grammatical rules. In

particular, ‘she’ is a third person singular pronoun

which should take a singular verb. In this case, ‘she’

should be followed by a singular auxiliary ‘is’. Both

teachers and students seem to have internalised this

rule, so they can decide correctly that aren’t is

incorrect.

Sentence 7: What did you bring that book to be

read out for to? (10 % of teachers and 45 % of

students judged correct). This sentence is problematic

because it contains three stranded prepositions at the

end of the question. A preposition is said to be

stranded if it is not followed by its complement and it

is chiefly found in interrogative clauses (Bieber, et al.,

2000: 105). Prescriptive grammarians have often

claimed that stranded prepositions are unacceptable

Teachers’ and Students’ Judgment of Grammaticality of Sentences

55

and should be avoided. However, in some cases,

stranded prepositions are normal where there is a

close relation between the preposition and the

preceding word, as in: Who are you looking for? Yet,

in sentence 7, the antecedents for the prepositions are

relatively far (what…for, bring…out, to be read…to).

Also, a single question usually uses one stranded

preposition, not three in a row.

Sentence 8: The plane that the pilot that the police

questioned flew crashed. (20% of teachers and 10 %

of students judged correct). This sentence is complex

because it contains center-embedding of relative

clauses. This sentence consists of three clauses that

can be written as:

[The plane [that the pilot (that the police

questioned) flew]] crashed.

Center-embedding poses an extreme processing

load for English speakers (Comrie, 1989: 27; Odlin,

1989: 97). However, processing difficulty does not

entail that his construction is ungrammatical.

Sentence 15: Susan trained like she’d never

done before. (0% of the teachers and 30% of the

students judged correct). The problem in this

sentence is the preposition like. Like in this case

functions as a preposition denoting a comparison,

similar to the preposition as. Following the

prescriptive grammars, as should link the first clause

Susan trained, with the comparative second clause

She’s never done before. The second clause is a

comparative clause marked by the use of present

perfect tense she had never done and the time signal

before. (Cobuild, 2005) describes that preposition

‘like’ and ‘as’ can be used to say that someone or

something is treated in a similar way to someone or

something else. (Huddleston & Pullum (2005) say

that like + finite clause is relatively informal but it

cannot be regarded as deviant. Most participants

focused on the use of different tenses in the first and

second clause so they judged this sentence as

incorrect.

Meanwhile the sentences that show the biggest

difference in perception are sentences number 16 and

17.

Sentence 16: I bought three mouses at the

computer stores. (35 % of the teachers and 80 % of

the students judged correct). ‘Mouse’ is a countable

noun which has an irregular plural form, i.e. mice,

instead of mouses. However, recently, the word

mouse is used as a technical term for computer

appliance. Oxford dictionary defines it as ‘a small

handheld device which is moved across a mat or flat

surface to move the cursor on a computer screen’. So,

the question is whether the plural of mouse in the

computing sense ‘mice’ or ‘mouses’? People often

feel that this sense needs its own distinctive plural,

but in fact the ordinary plural ‘mice’ is more

common, and the first recorded use of the term in the

plural (1984) is ‘mice’.

Sentence 17: There is only one person who thinks

of themself. The use of they/them/their to refer to a

singular person whose gender is unknown is

controversial (Leech & Svartvik, 2002: 58) Yet, the

pronouns they or them can be used for indefinite

pronouns such as someone or anyone (Cobuild,

2005). Some people say it is wrong to use them for

singular but clumsy to use him or her because it only

suggest that the person is a male or a female. Another

problem is the reflexive form themself. In themselves,

the plurality is double-marked (them+selves), while

the noun is singular (one person), so the term themself

is used. Biber, et al. (2000:343) note that the form

themself sometimes occurs in the news corpus to fill

the need for a dual gender singular reflexive pronoun.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study show that students and

teachers have different perceptions regarding the

grammaticality of sentences. In general, the teachers

found more ungrammatical sentences than the

students. The teacher group only judged 31.43 % of

the sentences as correct or grammatical; while the

student group judged 44 % of the sentences as

grammatical. The results indicate that teachers were

able to find more ‘mistakes’ in the sentences given. It

is possible that the teachers are ‘rules sensitive’

meaning that they can spot irregularities immediately.

For example, when they see the word ‘mouses’, most

of the teachers consider this word as incorrect. On the

contrary, some of the students might be ignorant of

the grammatical rules. Thus, they tend to judge the

sentences as grammatical rather than finding the

irregularity in the sentences.

The findings of this study confirm Rimmer's

(2006) indication that there are three competing

motivations for rating the sentences as grammatical

or ungrammatical. Those are: (1) appeal to usage; (2)

appeal to rules; and (3) ignorance. In the case of the

teacher participants, the first and second motivations

apply to them. On the contrary, the most of the

students show the ignorance to the rules.

Finally, the question of which sentence is

grammatical and which is ungrammatical cannot be

answered in a clear-cut fashion. Rimmer (2006)

claimed that grammaticality judgment tests do not

offer conclusive evidence to support the legitimacy of

a specific construction. There is also no simple

answer to the question posed by Han & Ellis (1998)

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

56

what are the grammaticality tests measuring? The

results of this study cannot be taken as a proof of the

grammaticality of sentences. Yet, they can be used as

the basis for further studies. Thus, how do the results

of this study affect the teaching of grammar for

foreign language learners?

First of all, grammar is not at all chaotic. There

are many very strong grammatical rules that can

inform learners which can be taken from prominent

grammar references (Oxford, Cambridge, Longman,

Collins Cobuild, etc.). In case of disputed usage,

teachers as well as students can turn into corpus for

practical reference (Vickers & Morgan, 2005).

REFERENCES

Biber, D., Johansen, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., Finegan, E.

2000. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written

English. Essex: Pearson Education.

Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (Vol.

11). Massachussetts: MIT Press.

Cobuild, C. 2005. Collins Cobuild English Grammar. New

York: Harper Collins.

Comrie, B. 1989. Language Universal and Linguistic

Typologie. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Dabrowska, E. 2010. Naive v. expert intuitions: An

empirical study of acceptability judgments. Linguistic

Review, 27(1), 1–23.

Dienes, Z., Scott, R. 2005. Measuring unconscious

knowledge: Distinguishing structural knowledge and

judgment knowledge. Psychological Research, 69(5–

6), 338–351.

Ellis, R. 2009. Implicit and explicit knowledge in second

language learning, testing and teaching (Vol. 42).

Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., Hyams, N. 2017. An

Introduction to Language (11th ed.). Boston: Cengage.

Han, Y., Ellis, R. 1998. Implicit knowledge, explicit

knowledge and general language proficiency.

Language Testing Research, 2(1), 1–23.

Huddleston, R., Pullum, G. 2005. A Student’s Introduction

to English Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Leech, G., Svartvik, J. 2002. A communicative grammar of

English. Essex: Pearson Education.

Odlin, T. 1989. Language Transfer. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Rebuschat, P., Williams, J. N. 2012. Implicit and explicit

knowledge in second language acquisition. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 33, 829–856.

Riemer, N. 2009. Grammaticality as evidence and as

prediction in a Galilean linguistics. Language Sciences,

31, 612–633.

Rimmer, W. 2006. Grammaticality judgment tests: trial by

error. Journal of Language and Linguistics, 5(2), 246–

261. Retrieved from

http://www.jllonline.co.uk/journal/5_2/LING 6.pdf

Schütze, C. T. 1996. The Empirical Base of Linguistics.

University of Chicago Press.

http://doi.org/10.17169/langsci.b89.101

Tabatabaei, O., Dehghani, M. 2012. Assessing the

reliability of grammaticality judgment tests. Procedia -

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31(2011), 173–182.

Tremblay, A. 2005. Theoretical and methodological

perspectives on the use of grammaticality judgment

tasks in linguistic theory. Second Language Studies, 24,

129–167.

Vickers, C., Morgan, S. 2005. Incorporating Corpora.

English Teaching Professional, 41, 29–31.

Teachers’ and Students’ Judgment of Grammaticality of Sentences

57