Teachers’ Perception and Attitude in Using Corrective Feedback

Associated with Character Education

Izef Puspadani Damanik, Arif Husein Lubis, Gilang Rajasa, and Dida Firman Hidayat

Department of English Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Setiabudhi 229, Bandung, Indonesia

{puspadani, husein.lubis07, rajasa7, raja.mahaputra08}@student.upi.edu

Keywords: Teacher’s perception, attitude, written corrective feedback, oral corrective feedback, character education.

Abstract: Recent developments in the field of corrective feedback have managed to a renewed interest that corrective

feedback might be interrelated with attitudinal development. Nonetheless, its appearance might be still vague

in Indonesian educational setting which emphasizes character education as the foremost foundation of

teaching and learning. This article seeks to capture Indonesian English teacher’s perception and attitude on

the use of corrective feedback and its association with character education. Employing a descriptive study,

this paper elaborates nineteen English teachers’ responses using open-ended questionnaire and interview. The

findings support the idea that implicit corrective feedback is preferable to the teachers rather than the explicit

one in delivering characters to their students. In addition, the study also highlighted some positive characters

taken from the teachers’ perspective. However, the result should be interpreted with caution since there are

some limitations this study could not provide.

1 INTRODUCTION

Feedback is one of the interactions mostly used by

teachers in the class. Hattie and Timperley (2007)

clearly state feedback as a ‘consequence of

performance’ that could be used explicitly or

implicitly. An abundance of study has exposed that

feedback implementation could improve student’s

cognitive (Al-Bashir, Kabir, and Rahman, 2016),

affective (Grawemeyer et al., 2015), and

psychomotor (Milde, 1988). Even so, the study done

by Karanezi and Rapti (2015) signaled some

differences in teachers' perception and attitude over

traditional and modern teaching method with positive

and negative results at their own classes. Another

study concluded by Halimi (2008) who found that

most teachers employ CF as a constructive means of

providing guidance for students to get them familiar

with grammatical and lexical patterns of good

English. However, most of the respondents prefer

explicit strategy to correct the students’ work by

crossing out the incorrect form and giving the correct

form. In contrast with Halimi, Mendez and Cruz

(2012) noted that most teachers believe that implicit

strategy was more preferred to use in correcting the

students’ errors compared to explicit one. Supported

by Park (2010), the implicit error correction would

likely influence student’s affective skills related to

character building such as autonomy and confidence.

Furthermore, Basalama and Machmud (2014) also

concluded the development of character building

could be facilitated by implementing corrective

feedback.

Reflected from the previous studies, there seems

no clear-cut evidence found regarding the concurrent

relationship between the preferences and types of

corrective feedback associated to the promotion of

character education in the process of students’ writing

and speaking assignment. Under those circumstances,

this study was aimed at seeking the perception and

attitude of Indonesian English teachers on corrective

feedback associated with character education.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Broadly speaking, corrective feedback (CF) is

defined as any strategy used by the teacher to ask for,

indirectly demand, students’ improvement on their

language awareness and language proficiency

(Chaudron, 1977). Therefore, two major strategies of

CF based on its form are written and oral corrective

feedback.

Written corrective feedback consists of six types:

direct, indirect, metalinguistic, unfocused, focused,

206

Damanik, I., Lubis, A., Rajasa, G. and Hidayat, D.

Teachers’ Perception and Attitude in Using Corrective Feedback Associated with Character Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0007164602060212

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 206-212

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

and reformulation. Meanwhile, oral corrective

feedback consists of six types: recast, repetition,

clarification, explicit, elicitation, and paralinguistic

signal. The description of each type of both corrective

feedbacks is provided in the following tables (Halimi,

2008).

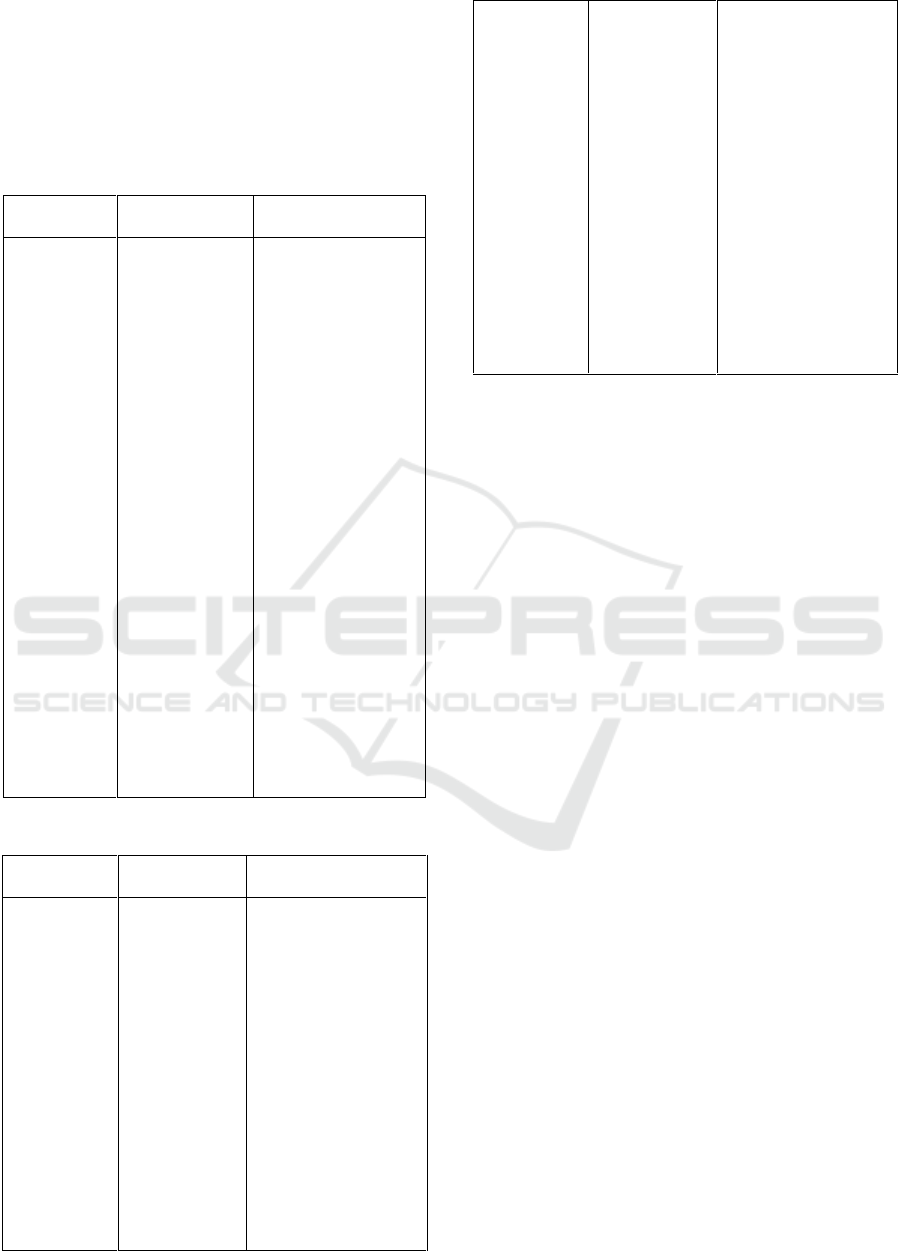

Table 1: Types of written corrective feedback.

Corrective

feedback

Type

Description

Written

Direct

Indirect

Metalinguistic

Unfocused

.

Focused

Reformulation

Teacher provides the

correct form.

Teacher indicates

that an error exists,

but no explanation.

It can be indicating

or plus locating the

error.

Teacher provides a

clue or code as the

helpful point to

correct the errors.

Teacher concerns to

most or all of the

errors identified.

Teacher concerns to

specific types of

errors only.

Teacher urges

students to rework

the content or

meaning of the text.

Table 2: Types of oral corrective feedback.

Corrective

feedback

Types

Description

Oral

Recast

Repetition

Clarification

Teacher incorporates

the content words of

the preceding

incorrect part and

changes and corrects

the error directly.

Teacher repeats the

expression and

highlights the error by

using emphatic stress.

Teacher questions

back the student

indicating that he/she

has not understood

the expression.

Explicit

Elicitation

Paralinguistic

signal

Teacher tells there has

been an error and

provides the

correction.

Teacher repeats some

parts of the

expression, but not

the erroneous part and

uses rising intonation

to signal that the

following part is the

erroneous one.

Teacher uses gesture

or facial expression to

indicate that there is

an error.

Recently, Indonesia has developed character

education to promote their students’ ability in life

skill and manner because Indonesia has several

diversities that should be united by tolerant behavior.

In 2004, Elkind and Sweet stated that character

education is a deliberate effort to help people

understand, care about, and act upon core ethical

values. Following Josephson's (2002) six pillars of

character education, as follows trustworthiness which

also concerns a variety of qualities such as honesty,

integrity, reliability, and loyalty, respect in all

situations, even when dealing with unpleasant people,

responsibility of being in charge of our choices and

being accountable for what we do and who we are,

fairness which probably more subject to legitimate

debate and interpretation than any other ethical value,

caring which is an honest expression of benevolence,

or altruism, and citizenship which includes civic

virtues and duties that prescribe how we ought to

behave as part of a community.

According to Indonesian Government Decree No.

20 in 2003, there are eighteen character values that

teachers should teach to the learners. The characters

are religious, honest, tolerant, discipline, hard work,

creative, independent, democratic, curious,

nationality passionate, loyalty to the nation, respect to

achievement, communicative, love peace, love to

read, care to the environment, social care, and

responsible.

3 METHODOLOGY

This study employed descriptive qualitative design

using an open- and close-ended questionnaire and an

interview protocol to gain teacher’s perception on and

attitudes toward corrective feedback. The

Teachers’ Perception and Attitude in Using Corrective Feedback Associated with Character Education

207

questionnaire was distributed to thirty teachers

purposively since they have more than five years

teaching experiences. However, only nineteen

teachers returned the questionnaire. They are

enrolling their Master degree at one state university

in Bandung, Indonesia, and at the same time teaching

at schools from different levels (elementary, junior

high, and senior high). Four teachers then volunteered

to be interviewed to further notice the belief of the

teachers.

The questionnaire is adapted from (Ellis, 2009);

Halimi (2008); and Kartchava (2016), with specific

adjustments to the need for the research. The

interview protocol was created based on the

questionnaire to obtain the respondents’ supporting

reasons or explanations. The former consists of four

parts. Part 1 consists of four questions used to obtain

information related to the personal background of the

respondents. Part 2 consists of eight questions used to

obtain information about their attitude toward

corrective feedback in students’ writing work: 4

multiple choice questions and 4 short essay questions.

Part 3 consists of eight questions concerning that on

using corrective feedback to students’ speaking

performance: 4 multiple choice questions and 4 short

essay questions. Part 4 consists of three questions

concerning their perception on using corrective

feedback in general in the forms of Likert-scale and

short-essay questions.

Meanwhile, the interview protocol was used to

obtain the respondents' reasons or explanations about

the preference and process of corrective feedback

practice in the classroom they have provided in the

questionnaire. It is intended to recognize what

characters are encouraged as the costs of their

preference on using a particular type of CF. The

interview protocol consists of three parts. Part A

consists of 5 questions used to obtain information

about their general perception and attitude on

students' errors and feedback. Part B and C consist of

6 questions respectively used to obtain information

about their perception of and attitude towards oral and

written corrective feedback.

The raw data gained were analyzed qualitatively

by employing Miles and Huberman (1994) four-step

data analysis model. The questionnaire results were

classified into two major themes: perception on and

attitudes toward corrective feedback within each oral

and written feedbacks are covered. Meanwhile, the

interview transcripts were firstly read and discussed

by each researcher regarding the emerging codes.

Then, the recurrent codes were classified into some

categories, i.e., perception, belief, attitudes,

preferences, and process. Lastly, these categories are

associated with the main themes, i.e., oral and written

corrective feedbacks that will directly address the

research question.

To gain data trustworthiness, the interview

transcript was distributed to the respective participant

to proofread any mistyped words. Besides, each

researcher re-checked the transcript for any

grammatical errors.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Teachers’ Perception of the Use of

Written and Oral Corrective

Feedback Strategies

The findings were aimed at addressing the first

research question, “how are the perception and

attitude of Indonesian English teacher on the use of

corrective feedback regarding the students’ writing

work and speaking performance?”

Furthermore, the open-ended questionnaire

indicated teacher's perception on the benefits of CF

implementation in English teaching and learning

process. It classified 3 different benefits – students,

teachers, and both – related to enhancement. In terms

of student's enhancement, 5 teachers perceived that

CF can help students to correct and minimize their

own errors as well as their motivation and knowledge

skill. In terms of teachers' enhancement, 5 teachers

believed that CF eased them to measure student's

achievement and progress. Eight (8) teachers believed

both sides were benefited from the use of CF in

classroom evaluation and teaching quality.

Regarding the learning experience, major

respondents (11) indicated that CF would provide

students with the information about the errors that

contribute to the student's language proficiency and

learning achievement. Further, it could be an

indicator of student's achievement in the classroom.

Taken from the interview dataset, teachers clarified

that CF may affect both teachers’ teaching quality and

students’ learning motivation.

4.2 Teachers’ Perception and Attitudes

on Corrective Feedback Associated

with Character Building

These findings were aimed to answer the second

research question "How are the teachers' perception

and attitude on corrective feedback associated with

character education?". Explicitly stated before, there

are 18 types of national character education in

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

208

character building development; Religious, Honest,

Tolerance, Discipline, Hard work, Creative,

Independent, Democracy, Curiosity, Nationality

Spirit, Nationality Loyalty, Achievement

Appreciation, Friendly or Communicative, Love

Peace, Love Reading, Environment Caring, Social

Caring, Responsibility. Other perceptions not related

to the aim of the study will be included at the end of

the chapter.

4.2.1 Written Corrective Feedback

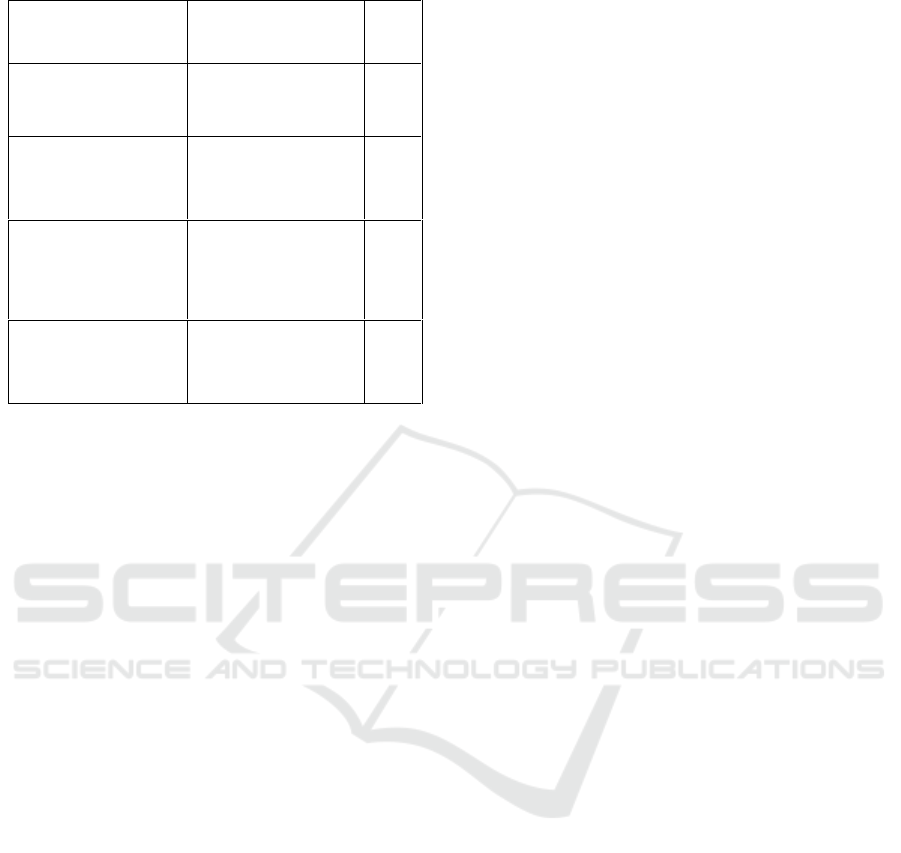

Table 3: Questionnaire result.

WCF Types

Types of corrective

feedback on writing

Tick

()

Direct

Crossing out the error

and providing the

correct form.

8

Indirect

Showing the error

and giving a

clue/editing symbol

to correct it.

6

Underlining or

circling the error.

2

Indirect + verbal

explanation

Putting a sign on the

incorrect parts and

providing oral

feedback as well.

1

Focused + verbal

explanation

Providing general

feedback in class on

common errors

2

Referring to the WCF typology, several types of

WCF were detected; direct, indirect, and focused.

However, the data also suggested that there is also a

verbal explanation or communication between the

teacher and the students in order to clarify the errors

and the feedback. Besides, the aforementioned

typology (Table 1) seems not clear enough to classify

the types of WCF since there is a possible relationship

in each type of WCF. It means, in a logical sense,

while direct and direct CF focus on the procedure of

providing the feedback, focused and unfocused CF

deal with the frequency of errors occurrence.

Meanwhile, reformulation CF concerns about the

coverage of the whole content. In contrast with the

literature, this article claims that there must be a

preceding classification which explains the

discrepancy of these types. Thus, focused, unfocused,

and reformulation types were not detected on the data.

Regarding the character education, the answers

expressed by the respondents were specified as

building awareness from the students’ errors. Some

respondents agree that by marking or pointing out the

error (indirect), the students would directly recognize

the error and the way to correct the error. Moreover,

one respondent claimed, with error correction

provision, students would be able to imitate the

correct answer. Also mentioned by one respondent, a

clue-type correction will trigger the students’ to be

more enthusiastic and thorough in doing their

assignments. Further, Sally, who prefers clue-type

written feedback, said:

“Some of the students really reflect it. I mean

that high-level students will tend to correct

themselves right away, but other students just

neglect it. Some try to consult it with me whether

the feedback is really helpful or not.” (Sally,

R9)

Based on Sally’s explanation, there is a

classification of students’ reflection based on their

level. According to her statement, while high-level

students would use CF in leading them to find the

correct answer, low-level students might ignore the

CF. By looking what Sally implied, a clue-type

correction will lead to a possible connection between

students’ types and self-understanding. R19 also

suggested that ‘teachers should not directly provide

the correct answer but let students repair the incorrect

one’. This type of CF creates a demanding situation

where the clues will lead students to be curious and

seeking the right answer and responsible at the same

time.

Two teachers believed the best way of giving

WCF is by signaling the error. They chose to provide

a signal (e.g., underlines or circles) on the error

without any note. To them students will be able to

think critically by asking the teacher of the error,

therefore teacher could provide detail feedback to the

students. Ward also argued:

“…with circling or underlining to the error (the

sentences or words), without providing any

note, would stimulate students’ curiosity to ask

questions to the teacher. Lastly, I explain their

errors one by one.” (Ward, R13)

Logically, types of WCF could be used as a tool

to promote character education in learning context

consciously or unconsciously. Conscious character

education means teachers would deliberately build

their students’ character with a demanding situation.

The demanding situation then could increase

students’ curiosity to seek correction of their errors.

An unconscious character education means teachers

are actually focused on the learning content but

indirectly lead the students to build their own

Teachers’ Perception and Attitude in Using Corrective Feedback Associated with Character Education

209

character. Thus, it will draw students’ consideration

by paying attention to the errors and the correction

(awareness) and being responsible to correct the

errors (responsibility). Most of the respondents in the

present study agree that character education would

possibly occur during their WCF implementation.

However, this perception might interfere with the

instruments used in this study since there is no

obvious explanation whether or not character

education is deliberately conducted.

In general, most teachers in the present study have

a similar perception that CF is used to avoid students’

confusion and create a motivational learning

atmosphere. It is because some students may lack

understanding of what should be done with the errors

(R17) or feeling demotivated to join the cause.

Therefore, these perceptions may result in building

students’ awareness. The awareness will then lead the

students to be more careful and pay attention to their

next performance. In other words, judging from

teachers’ perspective, while students’ awareness of

their error is already maintained, it might probably

lead them to be responsible for their later

performance.

Regarding the approach used in the process of

providing corrective feedback on the students’

written works, explicit explanation and direct error

corrections were the most preferred ways represented

by 10 respondents. Two (2) respondents did not

provide any explanation about the rationale of their

using in which it becomes quite ambiguous to reflect

on whether character education is asserted in the

learning process. On the other hand, 7 other

respondents argued that they preferred to employ

strategies emphasizing student-centeredness. They

mostly concerned to the students’ responsibility in

which direct guidance and guided clues were

employed.

It is in line with the interview results suggesting

that by providing notes on the correction would

encourage the students to figure out how to correct

the errors under their guidance. In contrast, providing

clues (e.g., circles or underlines), without any notes,

would stimulate their curiosity. These perspectives,

eventually, have a similar result in nature. It reflects

that even though the participants are different in ways

of addressing their feedback, however, the expected

result is actually to take over students’ awareness and

curiosity in the learning process.

“...I provide the feedback by writing it down on

each student’s paper. After that, I invite all

students to discuss it together focusing only on

the repeated errors.” (Eddie, R19: L44, 45)

Additionally, related to the teacher’s attitude

towards the same context, the datasets deduced the

use of WCF would trigger to be autonomous and

responsible at the same time. However, teachers’

holistic correction such as clues, editing symbols,

direct correction, explicit correction still become the

major reasons for such attitudes. By far, according to

the teachers, students are still dependent on it.

4.2.2 Oral Corrective Feedback

Before elaborating the data, the article would

underline the context of speaking performance. Since

the performance might be, to some extent, interpreted

as a daily interaction between the teacher and the

students, the activities emphasized in this article are

students' interaction e.g. telling stories, debating,

transactional and interpersonal dialogue.

Table 4: While-perform corrective feedback.

OCF Types

Types of corrective

feedback on speaking

Tick

()

Clarification

By directly

interrupting and

asking for

clarification what has

the student said

3

Explicit

By directly

interrupting, telling

the incorrect part(s),

and giving the correct

form

4

Elicitation

By directly

interrupting and

repeating some parts

of the utterance

before the incorrect

part(s) by rising the

intonation on the last

word before the

incorrect part(s)

2

Sign paralinguistic

By directly

interrupting through

the use of gestures or

fingers to show the

incorrect part(s)

1

The data also disclosed another possibility in

providing the feedback. Nine respondents would

imply that feedback should be given at the end of the

performance (post-perform), while the others in the

middle of the performance (while-perform).

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

210

Table 5: Post-perform corrective feedback.

OCF Types

Types of corrective

feedback on

speaking

Tick

()

Waiting (Without

notes)

Feedback provided at

the end of the

performance

3

Waiting (without

notes + reward)

Give reward and

provide feedback at

the end of the

performance.

1

Waiting + with notes

Make a note of the

errors and provide

feedback at the end of

the performance.

4

Unclassified

(Indecisive)

Collect the students’

errors and provide

feedback at the end of

the lesson.

1

Four of nine respondents preferred taking notes of

the errors before providing the feedback. The other

three respondents would give feedback at the end of

the performance without preparing any notes. In a

similar way, the other one would firstly give rewards

before feedback is given. However, one indecisive

response was detected since there was no clear

explanation whether the notes were prepared.

Seeing the perspective of the teacher, there are two

types of oral corrective feedback; while-perform type

and post-perform type. While the former is given in

the middle of speaking performance, the latter is

given at the end of student’s speaking performance.

To some respondents, the perception of the use of

post-perform type correction would not distract the

students’ concentration span and maintain students’

motivation in generating ideas of their talking.

Suggested by interview datasets, some interviewees

believe post-perform type would maintain students’

confidence, carefulness, and precision. Moreover, as

a respondent noticed, giving correction after the

students’ speaking performance would initiate

students’ acceptance towards the correction.

On the contrary, a different perception was

gained. The interruption in while-perform type is a

short-intervention feedback which is more positive

than a long-intervention feedback. Within this type,

the respondents believed students being accustomed

to critical thinking and thoroughness could be

maintained. To some other proponents, awareness

could be perceived as soon as students commit errors

while they perform.

Towards the attitude on the use of oral corrective

feedback, some teachers were positively

(consciously) slipping character education while they

used corrective feedback. The intention of it was to

make the students responsible and autonomy of their

errors. To the others, teachers negatively

(unconsciously) slipping character education on their

correction. However, the teachers agreed on

interruption on students' speaking performance will

lead to losing concentration and decrease in terms of

motivation; therefore, taking notes was preferable to

do.

5 CONCLUSION

This article has reached the conclusion that there were

several types of WCF and OCF. Regarding the

former, there is a limitation of a theory that could

explain all types of WCF mentioned by the

respondents. It would likely happen since there is an

overlapping feature of each type that could not be

properly interpreted on the result of the study.

Regarding the latter, there should be an additional

classification which explains how the feedback is

given (whether in the middle or at the end of the

performance). Therefore, this article would eagerly

suggest that the existing literature should be expanded

in terms of the classification of types of WCF and

OCF.

Based on the finding, there are three types of

character education displayed in implementing

corrective feedback; curiosity, responsibility, and

achievement appreciation. However, more positive

affection such as motivation, awareness, critical

thinking, and confidence are also presented in

corrective feedback.

Driving from WCF and OCF, there are types of

correction that could promote positive character

learning directly or indirectly and conscious and

unconsciously. Further, teacher’s perception may

influence the result of character learning in correction

feedback. Those lead to the process of

accommodating character education itself in using

either written or oral corrective feedback strategies.

Regarding the former, explicit CF strategy strongly

tends not to trigger students’ involvement from which

neglection and dependency were mostly indicated.

On the other hand, the teachers emphasizing student-

centeredness through implicit CF strategy conforms

to the promotion of character education, which

comprise; curiosity, autonomy, and carefulness.

Regarding the latter, the majority also confirmed

similar consideration that students’ involvement in

the process of providing the feedback becomes the

basis of their choosing implicit CF strategy. As a

Teachers’ Perception and Attitude in Using Corrective Feedback Associated with Character Education

211

result, self-confidence, bravery, and competence of

the students were majorly accommodated. Thus, the

choice of a particular strategy fundamentally

influences the students’ attitude toward the feedback

in which a revisit on the actual practices of providing

the feedback and actualizing sensitivity upon the

students’ circumstances might contribute to the better

quality of character education accommodation

through either written or oral CF strategies.

REFERENCES

Al-Bashir, M., Kabir, R. & Rahman, I., 2016, ‘The value

and effectiveness of feedback in improving students’

learning and professionalizing teaching in higher

education’, Journal of Education and Practice, 7(16),

pp. 38–41.

Basalama, N. & Machmud, K., 2014, Peran Role Model

dalam Pembelajaran Bahasa Inggris pada Konteks

‘Foreign Language': Suatu Penelitian Kualitatif

Tentang Identitas & Budaya dalam Pembangunan

Karakter Bangsa. Universitas Negeri Gorontalo.

Available at: http://repository.ung.ac.id

Chaudron, C., 1977, ‘A descriptive model of discourse in

the corrective treatment of learners’ errors’, Language

Learning, 27(1), pp. 29–46.

Elkind, D. H. & Sweet, F., 2004, ‘How to do character

education’, Live Wire Media. Available at:

http://www.goodcharacter.com/Article_4.html.

Ellis, R., 2009, ‘A typology of written corrective feedback

types’, ELT Journal, 63(2), pp. 97–107.

Grawemeyer, B. et al., 2015, ‘The impact of feedback on

students’ affective states’, CEUR Workshop

Proceedings, 1432, pp. 4–13.

Halimi, S. S., 2008, ‘Indonesian teachers’ and students’

preferences for error correction.’, WACANA, 10(1), pp.

50–71.

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H., 2007, ‘The power of feedback’,

Review of Educational Research, 77(1), pp. 81–112.

Josephson, M. S., 2002, Making Ethical Decisions. Los

Angeles: The Josephson Institute of Ethics.

Karanezi, X. & Rapti, E., 2015, ‘Teachers ’ attitudes and

perceptions : Association of teachers ’ attitudes toward

traditional and modern teaching methodology

according to RWCT as well as teachers ’ perceptions

for teaching as a profession’, Creative Education, 6, pp.

623–630.

Kartchava, E., 2016, ‘Learners’ beliefs about corrective

feedback in the language classroom: Perspectives from

two international contexts’, TESL Canada Journal,

33(2), pp. 19–45.

Mendez, E. H. & Cruz, M. del R. R., 2012, ‘Teachers’

perceptions about oral corrective feedback and their

practice in EFL classrooms’, Profile Issues in

Teachers’ Professional Development, 14(2), pp. 63–75.

Milde, F. K., 1988, ‘The function of feedback in

psychomotor-skill learning’, Western Journal of

Nursing Research, 10(4), pp. 425–434.

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M., 1994, Qualitative Data

Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks,

USA: Sage Publication, Inc.

Park, G., 2010, ‘Preference of corrective feedback

approaches perceived by native English teachers and

students', The Journal of Asia TEFL, 7(4), pp. 29–52.

Presiden Republik Indonesia, 2003, Undang-Undang

Republik Indonesia no 20 tentang Sistem Pendidikan

Nasional, Direktorat Pendidikan Menengah Umum.

Indonesia. Available at:

http://www.kelembagaan.ristekdikti.go.id.

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

212