French Où-relatives and Que-relatives Expressing Time Produced by

Indonesian Students Learning French at B1 Level

Tri Indri Hardini and Dudung Gumilar

Departement of French Education, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudhi No. 229, Bandung, Indonesia

dudunggumilar@upi.edu

Keywords: Interlanguage, French, Relative Clauses, Indonesian Students.

Abstract: This paper aims to analyse French interlanguage occurrence of 63 French language students at Universitas

Pendidikan Indonesia. The purpose of this research especially to describe the interlanguage phenomenon

that occurs in the acquisition process of French où-relative and que-relative expressing time. The method

used in this study is qualitative descriptive method. The data collected through a test which consists of

productive and receptive questions. The results showed that the interlanguage occurrence can be explained,

and most students ability in forming ou-relative and que-relative for expressing time were high and close to

native speakers’.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper discusses interlanguage in French. The

topic discussed here is the acquisition of French

relative clauses focussing on investigating the

competence of the formation of relative clauses

owned by French learners who are at level B1 at a

state university in West Java Indonesia. The data in

this study were (1) où-relative where où means yang

in Indonesian and when in English, and (2) que-

relative where que also means yang in Indonesian

but that in English. Both clauses above state the

time. An example of que-relative is (1) Un jour que

je sortais. ‘One day when I was going out’ and an

où-relative example is l'hiver où vous détestez. The

winter that you hate.

The main difference between (1) and (2) above,

according to Hawkins and Towell (2007) using

Grammar Usage approach, is that où-relative is

formed when the head is a definite element (eg the

head le moment ‘the time’) whereas que-relative is

made when the head is indefinite (eg. the head un

jour). But unfortunately, Hawkins and Towell

(2007) do not provide underlying structure that can

distinguish the position of où ‘when’ and que ‘that’

in the constructions. Therefore, this paper adopts the

structure of French où-relative and que-relative

form, in particular (Prevost, 2009; Chomsky, 1995;

Jones, 1996; Benţea, 2010; Prentza, 2012;

Huhmarniemi and Brattico, 2013; Fiorentino, 2007;

Koenig and Lambrecht, 1999; Gallego, 2005).

Figure 1: The structure of French où-relative and que-

relative form.

According to Figure 1, the position of où-relative

occupied by the question word où is SpecCP

whereas in que-relative, the position taken by que is

under the C(omplementizer). Based on Prevost's

proposal, learners who have competencies to form

où-relative and que-relative formation are those who

have mastered some assumptions of relative clause

formations. First, French relative clause behaves

like embedded wh-questions. Second, relative

clauses involve C element that has a strong [+ wh]

feature not interpretable by semantics; (b) feature

[+wh] of C must be removed by involving wh-

movement word question où (also has [+ wh] ) and

Operator movement (also has features [+ wh]) for

que-relative. Thirdly, in où-relative, the question

754

Hardini, T. and Gumilar, D.

French Où-relatives and Que-relatives Expressing Time Produced by Indonesian Students Learning French at B1 Level.

DOI: 10.5220/0007174507540757

In Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference

on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education (CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017) - Literacy, Culture, and Technology in Language Pedagogy and Use, pages 754-757

ISBN: 978-989-758-332-2

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

word où moves from IP to SpecCP to remove the

feature of [+ wh] belonging to C marked by co-

indexed between l'hiver ‘winter’ (definite DP) with

the question word où and finally formed où-relative

where DP l'hiver ‘winter’ has a predicate où voùs

detestez ‘that you hate’. Fourthly, in que-relative,

Operator moves from IP t (indefinite DP) and OP

and finally forms que-relative where DP un jour

‘one day’ has predicate que je sortais ‘that I left’.

Finally, in the IP structures, the subject DP of Je ‘I’

and Vous ‘you’ occupy the SpecIP to obtain

Nominative Case and all verbs under I to have

agreement between subject and verbs for example

Tense [± Past] and Agreement [+ Number, +

Gender, + Person]. The structure in (1) will be used

as French representation of the où-relative and que-

relative that the students must master. In the context

of interlanguage, this paper aims at describing the

students level of interlanguage in mastering French

relative clauses, in particular où-relative and que-

relative relative.

2 METHODS

This study used qualitative approach. The subjects

are 63 students learning French at B1 level. The

object of this paper is the grammatical competence

owned by those students. The data used to explain

the grammatical competence is où-relative and que-

relative. This study used theoretical syntax of the

Minimalist Program of Generative Grammar to gain

the underlying structure and grammatical

competence needed to form où-relative and que-

relative. The instrument to collect data is test which

consists of productive and receptive tests. Students

are declared to be successful if they reach 75% of

each test. The data analysis is to compare between

the results of the tests against the assumptions

imposed to form où-relative and que-relative.

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

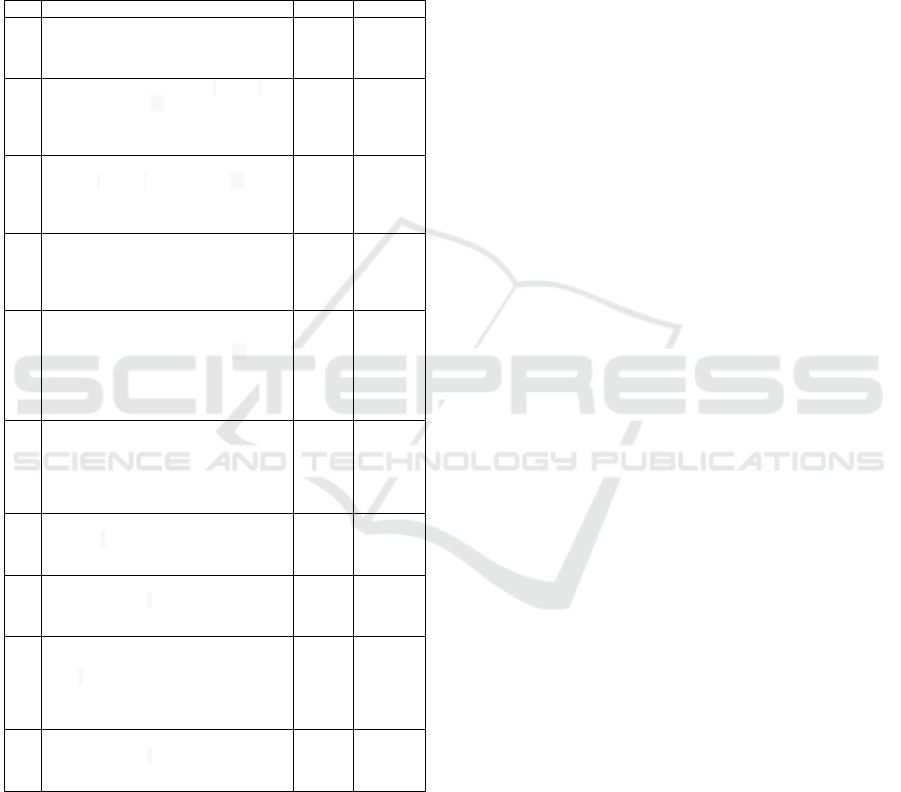

The results of the productive test in table 1 and

receptive test in table 2 show that the majority of

learners have had the competency to form où-

relative and que-relative. They have reached the

level of near native speakers of French. The students

who make mistakes are caused by their inability to

compose où-relative and que-relative. In table 1 it

can be seen that the item test consists of 6 items of

où-relative and 4 items of que-relative.

Table 1: Productive Test.

No. Relative Clauses Ri

g

ht

1 regardais, / au / me / le /moment / dos / où-que / je /

vous / vous /tourniez

Le moment

i

[CP où

i

[IP je vous regardais vous me

tourniez le dos

ti

]]

The moment when I watched you, you turned your

b

ac

k

84,13 %

2 viendra / attend / on / où-que / le / la / pluie / jour

On attend le jour

i

[CP où

i

[IP la pluie viendra

ti

]]

We are waitin

g

for the da

y

when the rain will come

85,71

3 où-que / me souviens / rencontré / jour / du / je / je /

l’ai

Je me souviens du jour

i

[CP où

i

[IP je l'ai rencontré

ti

]]

I remember the da

y

when I met hi

m

96,83

4 le / hier / plus / c’était / j’aimais / où-que

C’était hier

i

[CP Op

i

que [IP j’aimais le plus

ti

]]

It was

y

esterda

y

that I loved the most.

90,48

5 détestent / où-que / lundi / certaines / le / est / jour

/personnes

Lundi est le jour

i

[CP où

i

[IP certaines personnes

détestent

ti

]].

Monda

y

is the da

y

that some

p

eo

p

le hate.

88,89

6 beaucoup / où-que / j’aime / hivers / les / neige / il

J'aime les jours de l’hiver

i

[CP où

i

[IP il neige

beaucoup

ti

]]

Ilike da

y

s of winter when it snowed a lot

87,3

7 jamais / jours / toi / avec / je / pourrais / ne / passé /

France / où-que / oublier / des / en / j’ai

Je ne pourrais jamais oublier des jours

i

[CP Op

i

que

[IP j’ai passé avec toi en France

ti

]].

I could never forget the days that I spent with you in

France

87,3

8 aimé / où-que / moment / jardin / des / ton / passé /

j’ai / avons / bien / nous / dans

J'ai bien aimé des moments

i

[CP Op

i

que [nous

avons passé dans ton jardin

ti

]].

I enjoyed the moment that we spent in your garden

79,4

9 où-que / temps / sérieusement / commences / il / tu /

serait / travailler / à

Il serait temps

i

[CP Op

i

que [tu commences à

travailler sérieusement

ti

]]

It is time that

y

ou start workin

g

seriousl

y

.

82,5

10 Détestez / j’attends / vous / l’hiver / où-que

J’attends le moment [CP où [IP Je peux vous

parler

ti

]]

I'm waiting for the moment when I can speak to yo

u

81

Based on data from table 1, the majority of

learners demonstrate their ownership of grammar

competence to form où-relative and que relative.

This is supported by the awareness of learner to

treats relative clauses as (1) embedded wh-questions,

(2) each relative clause invertigated has a C element

that hat features [+ wh], (3) to form où-relative, the

learner feels the necessity to replace the [+wh]

feature of C with the [+ wh] feature of the question

word où through wh-movement and put it in

SpecCP, (4) wh-movement creates the co-index

between the DP head with the où question and (5) to

form que-relative, the learner has an intuition to

remove the [+ wh] feature of C with the [+ wh]

French Où-relatives and Que-relatives Expressing Time Produced by Indonesian Students Learning French at B1 Level

755

feature of Operator through the Operator movement

and put the Operator in SpecCP, 6) all learners

know that all IPs as the predicates of the head

Determiner Phrase.

The result of receptive test supports the success

achieved by learners. The majority of students are

able to distinguish between où-relative and que-

relative.

Table 2: Productive Test.

No. Relative Clauses Ri

g

ht Wron

g

1

1 2010 est l'année

i

[CP où

i

[IPJérôme a

obtenu son diplôme

ti

]].

2010 is the

y

ear that Jerome

g

raduated.

90,48

2 Le printemps, c’est la saison

i

[CP où

i

[IP

tout recommence

ti

]].

Spring is the season when everything

starts a

g

ain.

90

3 La naissance de mon fils, c’est le grand

moment

i

[CP où

i

[IP j'attendais

ti

]].

The birth of my son is the big moment

that I was waitin

g

for.

83

4 Il est parti le jour [CP qu[IP ’il s'est mis

à faire du soleil

ti

]].

He left the day that he started to

sunbathe.

82,54

5 Lundi prochain, c’est le jour [CP que [IP

j’attends impatiemment parce que mon

ami français va v enir chez moi

ti

]].

Next Monday is the day that I look

forward to because my French friend is

comin

g

to m

y

p

lace.

84.13

6 Dimache, c’est le jour [CP que [IP

j’adore car toute la famille se réunit chez

moi

ti

]].

Sunday is the day that I love because

the whole famil

y

meets at m

y

p

lace.

87,3

7 1999 c’est l’année [CP où [IP j’etais

heureux

ti

]]

1999 is the

y

ear when I was ha

ppy

.

85,71

8 Octobre, c'est le mois [CP que [IP les

feuilles tombent

ti

]].

October is the month that leaves fall.

85,71

9 Je me souviens toujours les jours [CP où

[IP mes parents sont passés à Bali sans

moi

ti

]].

I always remember the days when my

p

arents went to Bali without me.

82,54

10 Dimanche, c’est le jour [CP qu’[on

attend ensemble

ti

]].

Sunda

y

is the da

y

that we wait to

g

ether.

87,78

1

According to French grammar taught in the teaching of grammar

although Hawkins and Towell claimed that it is acceptable by French

native s

p

eakers.

Based on data from Table 2, the grammatical

competence to form où relative and que-relative is

generally acquired by the majority of learners

because students know that, (1) the clause structure

is relatively similar to embedded wh-questions, (2)

the C element in the structure contains [ + wh]

feature, (3) où-relative formation involves overt wh-

movement because the [+ wh] feature of C must be

deleted by the feature [+ wh] belonging to the

question word où and places it in SpecCP, (4) the

coindex determines the relationship between the

head DP forming the head and predicate relationship

and (5) in que-relative, the learner must remove the

[+ wh] feature C with the feature of [+ wh] of

Operator through the Operator movement and place

the Op in SpecCP so that the co-index between the

head DP and the element que is established and (6)

all relative clauses are acceptable because each

consists of head DPs and its predicates.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The approaches of Grammar Usage and the

Minimalist Program provide description of semantic

and structural differences between où-relative and

que-relative. Both relative clauses are successfully

acquired by average more than 80% of subjects who

have near native level of French interlanguage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writers would like to thank the head of French

Language Education Department of Indonesia

University of Education who has assisted this study.

REFERENCES

Jones, M. A., 1996. Foundations of French syntax.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hawkins, R., and Towell, R., 2007. French Grammar and

Usage. London: Edward Arnold.

Prevost, P., 2009. The Acquisition of French. The

Development of Inflectional Morphology and Syntax

in L1, Bilingualism adn L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins B.V.

Prentza, A. I., 2012. Second Language Acquisition of

Complex Structures: The Case of English Restrictive

Relative Clauses. Theory and Practice in Language

Studies, 2(7), pp. 1330-1340.

Huhmarniemi, S., and Brattico, P., 2013. The Structure of

Finnish Relatíve Clause Finno-Ugric. Languages and

Linguistics, 2(1), pp.53-88.

Fiorentino, G., 2007. European relative clauses and the

uniqueness of the Relative Pronoun Type Rivista.

Linguistica, 19(2), pp. 263-291.

Koenig, J., Lambrecht, 1999. French Relative Clauses as

Secondary Predicates: A case study in Construction

Theory. Center for Cognitive University of Texas at

CONAPLIN and ICOLLITE 2017 - Tenth Conference on Applied Linguistics and the Second English Language Teaching and Technology

Conference in collaboration with the First International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education

756

Austin Science and Linguistics Department, SUNY at

Buffalo.

Gallego, A. J., 2005. T-to-C Movement in Relative

Clauses. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de

Barcelona.

Benţea, A., 2010. On Restrictive Relatives In Romanian:

Towards A Head-Raising Analysis. Retrieved on 3

October 2017 from:

http://www.unige.ch/lettres/linge/syntaxe/journal/Volu

me6/anamaria_final.

Chomsky, N., 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge:

The MIT Press.

French Où-relatives and Que-relatives Expressing Time Produced by Indonesian Students Learning French at B1 Level

757