Towards a Cyber Security Label for SMEs: A European Perspective

Christophe Ponsard, Jeremy Grandclaudon and Gautier Dallons

CETIC Research Centre, Charleroi, Belgium

Keywords:

Cyber Security, SME, Security Controls, Information Security Management System.

Abstract:

Most SMEs underestimate or minimize the cyber security risks they have to face. Moreover, they are not

aware that the security context is changing rapidly at different levels. At legislative level, new reference

frameworks are created such as the GDPR. At normative level, security standards are evolving and increasingly

required. At technical level, threats and technologies are progressing in parallel making security control and

management a complex task. This position paper presents our approach and current progress in developing a

cyber security label for SMEs supported by accredited third party companies expert in this field. The pursued

goal is to raise the awareness of SMEs w.r.t. cyber security and to help them achieving and maintaining

an adequate level of protection. We position our work in the landscape of existing frameworks and similar

labelling initiatives developed in other European countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Our world is now hyper-connected with new tech-

nologies like Cloud, Internet of Things, Big Data de-

veloping at a fast pace. Many companies are eager to

adopt them given the high potential of value creation

through new business models (e.g. SaaS) or simpli-

fied IT management (e.g. Cloud hosted IT infrastruc-

ture). In this evolution, cyber security is often over-

looked while at the same time it involves new security

threats and ever increasing exposure to attacks. The

2016 report of the US-CERT to congress shows that

over the past ten years, reported incidents have been

multiplied by 14 with a double digit annual grow of

roughly 30% (Slye, 2016) (Donovan, 2016).

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are

known to play a key role in the worldwide economy.

In European countries they employ 2/3 of the work-

force and generate about 60% of the total added value

(Muller et al., 2015). SMEs are characterised by a

high degree of flexibility, a multitasking staff, a fo-

cus on the innovative development of a limited num-

ber of products or services and a low adherence to

procedures and standards. Regarding cyber security,

SMEs might just not be aware of the threats on their

business or think they are not worth being tackled.

Many also just have a false sense of security. This was

true to some extend in the past but the situation has

completely changed over the past few years (Smith,

2016). Different sources report that about half of cy-

ber attacks actually target SMEs (Symantec, 2017).

The main reasons is that SMEs are easy targets with

a good value vs risk ratio: most of the time, they un-

derestimate their data value (e.g. high-tech start-up)

(Hayes and Bodhani, 2013). SMEs can also be used

as relays towards bigger targets (Osborn et al., 2015).

Unfortunately most don’t get a second chance, as an

estimated 60% of companies go out of business within

a semester after being attacked (Leclair, 2015).

To face this evolution the market has already re-

acted and it becomes more and more frequent for

SMEs to be questioned about their cyber security pre-

caution in a call for tender process or to have spe-

cific clauses added to their contracts (CybSafe, 2017).

Public authorities are also reacting and have identi-

fied the need to help but also to force SMEs to adopt

a mature approach to face cyber security threats. At

European level, the main on-going initiatives are:

• The European Union Agency for Network and In-

formation Security (ENISA) is conducting sur-

veys and publishing specific guides addressing

SMEs cyber security needs. ENISA also issued a

number of recommendations to increase the level

of adoption of security standards by SMEs. In ad-

dition to easing the access to knowledge and in-

cluding SMEs in the standard development and

review process, it also proposes the definition of

certification schemes and the creation of standards

specifically tailored for SMEs. It stresses the need

of low cost and lightweight approaches that can fit

426

Ponsard, C., Grandclaudon, J. and Dallons, G.

Towards a Cyber Security Label for SMEs: A European Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0006657604260431

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018), pages 426-431

ISBN: 978-989-758-282-0

Copyright © 2018 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

SMEs capabilities (ENISA, 2015).

• The European Digital SME Alliance fosters the

SME ecosystem by developing a “EU trusted so-

lution” label that would stress European qualities

like data protection and high security standards.

It would also accelerate the development process

across the ecosystem and act as a differentiator es-

pecially to increase the international visibility of

European SMEs (Digital SME Alliance, 2017).

• The European Commission is investigating the

possibility of creating a framework for certifi-

cation of relevant ICT products and services.

It would be complemented by a voluntary and

lightweight labelling scheme for the security of

ICT products (EU, 2016).

• To improve the protection of personal data, the EU

has issued a new General Data Protection Regula-

tion (GDPR). (EU, 2016). It will be enforced in

May 2018 and comes at the price of a strict data

protection compliance regime with severe penal-

ties. Demonstrating cybersecurity maturity will

thus be part of measures to avoid data breaches.

While the idea of some form of labelling is clearly in

the air, the following caveats should be avoided, as

stressed by Digital Europe (Alex Whalen, 2017):

• As cyber security has no border, EU should take

into account the existing international ecosystem.

• A new EU certification scheme cannot be the

unique answer in a complex cyberspace.

• False sense of security possibly induced by la-

belling should be complemented e.g. by bench-

marking of security practices

• Avoid rigid and costly schemes: the approach

should be affordable by SMEs and allow some

form of voluntary and agile self-certification.

As many other countries, the need to better sup-

port SMEs has also triggered an initiative to define

and deploy a cyber security labelling scheme oper-

ated by a network of third party expert companies,

supported by specific public funding (e.g. cyber se-

curity vouchers). As highlighted above, such a work

should not be done in isolation but as much as pos-

sible aligned with strategic directions. It should also

rely on similar existing or on-going work carried out

in other countries having progressed on this topic.

The aim of this position paper is therefore to out-

line the main directions to build a realistic cyber secu-

rity labelling approach addressing the needs of SMEs.

Its overall goals should include raising awareness and

helping them reach a first level of assurance and matu-

rity. The process followed was to perform an in-depth

review of existing frameworks and emerging national

labels. Those were ranked against a number of re-

quired criteria for their adoption by SMEs. We also

collected existing feedback, especially about specific

barriers reported to deploy a specific approach.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 iden-

tifies relevant constraints and needs SMEs have to

face when dealing with cyber security. Section 3 gives

an overview of the existing approaches in the light of

those needs. In this light, Section 4 highlights a pro-

posed realistic approach. Finally, Section 5 describes

our roadmap to implement such a label in Belgium.

2 SMEs NEEDS ABOUT

INFORMATION/CYBER

SECURITY

A survey made in 2014 among UK SMEs shows

some interesting findings about their perception and

approach of cyber security (Osborn et al., 2015):

1. Only 21% of the respondents have shown a low

awareness about basic security guidelines.

2. One of the main reported barriers is the lack of

trust and quality regarding available information,

amongst others such as the lack of resources or

knowledge.

3. 39% have done an in-depth risk analysis including

cyber security and 48% keep the company’s risk

analysis, policies and backups up to date.

4. Most SMEs are aware of the reasons why cyber

security measures are necessary.

5. The cost is still the main barrier for implementing

cyber security solutions and standards, as those

are designed for bigger companies.

The bottom line is that most SMEs already have

a good level of awareness and are ready to devote re-

sources to cyber security. However they lack “simple

effective measures that are not too time-consuming

and require a great in depth knowledge of IT sys-

tems”. This lack of reliable sources of truth and guid-

ance is a huge hindrance for them and the perceived

incentives are not sufficient to break that barrier.

Given the limited space, we just give an overview

of the main requirements gathered from different

surveys (Boateng and Osei, 2013)(Osborn et al.,

2015)(Padfield, 2015) and our own interactions with

local SMEs. They are structured according to the

FFIEC Cybersecurity Domains:

• Management and oversight: the whole organisa-

tion should be committed with management sup-

port. A dedicated person should be identified and

given resources. Roles could be aligned with risk

management process to make the link with the

Towards a Cyber Security Label for SMEs: A European Perspective

427

company assets. Some internal training/aware-

ness should be organised. A plan-do-check-act

type of governance should be set up.

• Intelligence and collaboration: guidelines should

be available for classical SME network architec-

ture (e.g. with/without central office).

• Controls: easy to implement controls should be

available. They must be easy to operate internally

with limited amount of outside expertise (e.g. to

help select and install adequate controls).

• External Dependency Management: external in-

terfaces should be clearly identified and related to

the assets to help identifying the protection level.

• Incident management and resilience: basic busi-

ness continuity actions should be available (in-

cluding backup strategy, alternative processes,...)

3 EXISTING LABELS AND

FRAMEWORKS FOR SMEs

This section reviews a few emerging labels focusing

on SMEs and bigger frameworks that can be adapted

to the needs identified in the previous section. In the

process, we eliminated some approaches too domain-

specific (e.g.IEC-62443 for industrial automation) or

without any track records with SMEs.

3.1 CyberEssentials (UK)

Cyber Essentials is a UK government scheme

launched in 2014 to encourage organisations to adopt

good practices in information security (UK Govern-

ment, 2016). It includes an assurance framework and

a simple set of security controls to protect informa-

tion from threats coming from the internet. It was de-

veloped in collaboration with industry organisations

combining expertise in Information Security (ISF),

SMEs (IASME) and standardisation (BSI).

Figure 1: Self-assessment proposed by Cyber essentials.

There are two level of certification: a basic level

which is based on a self-assessment that can be in-

dependently verified and a ”plus” level featuring a

higher level of assurance through the external testing

of the organisation’s cyber security. Certifying Bodies

are licensed by 5 Accreditation Bodies which are cur-

rently appointed by UK government. Figure 1 shows

part of the proposed self-assessment questionnaire.

In order to support SMEs in adhering to the ap-

proach, the UK government has deployed a specific

voucher scheme including coaching, documentation

and certification. It was quite successful: more than

2000 Cyber Essentials and Cyber Essentials Plus cer-

tifications have been issued since the launch. Once

certified, the SME can also advertise about the fact it

takes cyber security seriously boosting its reputation

and providing a competitive selling point.

3.2 BSI and VDS (Germany)

A German cyber security act has been issued in 2010

to face the rise of cyber crime. A concern is the im-

pact of certification on companies. Compliance mea-

sures have to reflect the “current state of the technol-

ogy” and this work has to be carried out by the Federal

Office for Information Security (BSI) for each sector.

To our knowledge, initiatives for SMEs are origi-

nating from the private sector, e.g. by VdS which has

developed certifications targeting manufacturers, ser-

vice providers and end consumers. Their scheme has

four levels, starting from self-assessment (see Figure

2 to the full ISO27001. The certification body ap-

proves service providers for the consultancy of infor-

mation security/cyber security for a limited time.

Figure 2: Self-assessment proposed by VDS.

3.3 ANSSI Certification (France)

The French government announced in 2015 their

new digital security strategy, led by the ANSSI (The

French Network and Information Security Agency)

and designed to support the digital transition of

French society. The ANSSI certification process is

based on the Common Criteria.

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

428

A French cyber security label was also created in

the wake of this new strategy and aimed only French

products and companies (ANSSI, 2014).

3.4 Italian Cyber Security Framework

The Italian government has published their Frame-

work in 2015, largely inspired from the framework

for improving critical infrastructure cyber security

(NIST), targeted to critical infrastructures. Their main

modifications can be found in a strong focus on the

Italian economic context (large numbers of SMEs)

and a dedicated part on the contextualization. A com-

pany willing to use the document should first establish

its context before selecting the right subcategory and

Framework Core, as in the ”vanilla” NIST. This a not

a standard but a common reference.

3.5 ISO27001 for SMEs

The ISO standard sets out more than 130 individual

security controls grouped into 11 key areas. Not all

controls have to be implemented, as they can be se-

lected on the basis of a professional risk assessment.

A SME will find that such a standard contains many

controls that are not relevant or appropriate to their

circumstances, but might occasionally be required by

a large customer or business partner to demonstrate

their level of compliance.

ISO previously produced a guide which is now ob-

solete w.r.t. the last version of the standard. Criticism

have also been raised on the lack of value-driven ap-

proach of this standard (Lieberman, 2011).

3.6 NIST Cyber Security Framework

The NIST Cyber Security Framework (NIST CSF) is

a US policy framework providing computer security

guidance for helping organizations to assess and im-

prove their ability to prevent, detect, and respond to

cyber attacks (NIST, 2014). It is not a prescriptive

standard but aims at defining a common language and

systematic methodology for managing cyber risk. It

is supposed to give a broad and stable base in cyber

security and the users have to adapt it to their needs.

It will not give to the board the acceptable amount of

cyber risks the company can tolerate or not, neither a

mythical ”all in one” formula to banish cyber attacks.

But it sure will enable best practices to become stan-

dard practices for everyone, via a common lexicon to

enable actions across diverse stakeholders.

The framework is organised around a sound set

of five concurrent and continuous functions address-

ing different steps to process cyber threats: Identify,

Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover. It also provides

progressive implementation tiers depicted in Figure

3. The framework can realistically be used by SMEs

(Sage, 2015) and is actually used by the Italian frame-

work described in Section 3.4.

Figure 3: NIST cyber security Framework Tiers.

3.7 ISSA5173 (UK)

The ISSA 5173 aims is to encourage SMEs to take

steps to secure their customers and employees data,

and raise awareness of the relevant legislation that ap-

plies to them regarding data security. Although the

standard does not seem to be actively developed, it

defines an interesting prioritization scheme depicted

in Figure 4 (ISSA, 2011).

Figure 4: Prioritization of security measures in ISSA5173.

3.8 Top 20 Critical Security Controls

In 2008, a consensus of defensive and offensive secu-

rity practitioners developed guidelines consisting of

20 key actions, called critical security controls that

organizations should take to block or mitigate known

attacks. Those controls support automated means to

implement, enforce and monitor them. They are also

expressed in terms easily understood by IT staff. Spe-

cific guides are also available to help SMEs imple-

ment them with low budget (Eubanks, 2011).

Initially developed by the SANS Institute, those

controls are now maintained by the Center for Internet

Security to keep addressing the highest threats. They

are organised in two progressive sets: the first 5 con-

trols focus on inventory and configuration manage-

ment and help eliminating most of the vulnerabilities

while the additional 15 controls help securing against

today’s most pervasive threats (CIS, 2016).

Towards a Cyber Security Label for SMEs: A European Perspective

429

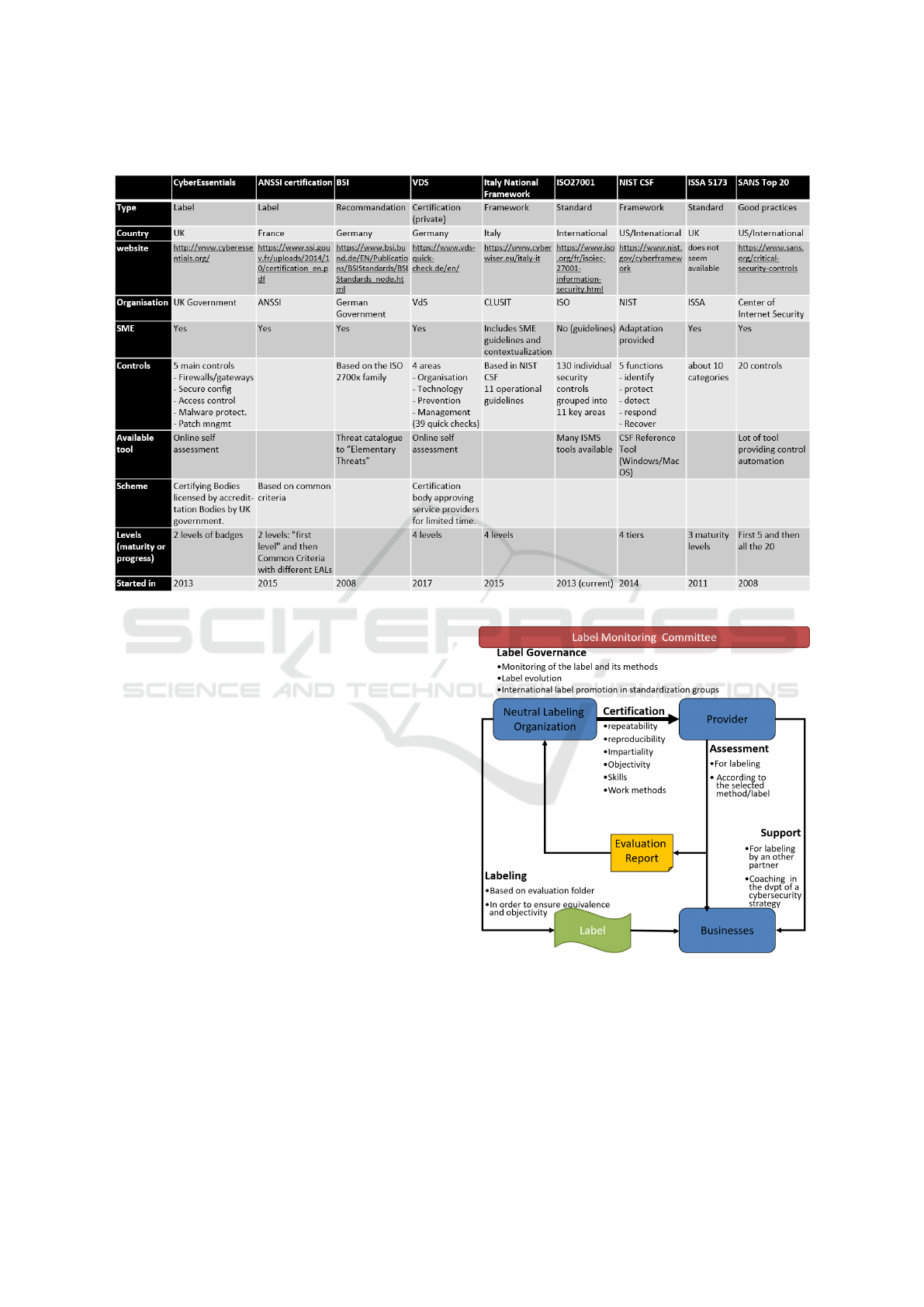

Table 1: Possible prioritization of security measures.

3.9 Comparison Summary

Table 1 summarises previous approaches. It eases

comparing and combining them to help with build-

ing our own approach without reinventing the wheel

and staying aligned with existing works.

4 OUR EMERGING APPROACH

Our label is aimed at any SME wishing to demon-

strate a level of maturity in information security. Its

purpose is to define the level of cyber security matu-

rity for an enterprise on a relevant scale. It would re-

flect a level reached by the company in terms of cyber

security and could be used by actors outside the com-

pany such as customers, suppliers, subcontractors, in-

surers or even computer crime investigators.

The envisioned approach is based on a framework

both strong and adaptable to SME needs like the NIST

CSF, similarly to the Italian approach. It would rely

on the five NIST categories and for each category use

the Tier approach as detailed in Section 3.6 which en-

ables a maturity scale. The global organisation is de-

picted in Figure 5, it includes both the certification

of provider that will be allowed to deliver the label.

To encourage SME to better protect themselves and

Figure 5: Proposed Labelling Scheme.

engage in the label, the public authorities have also

launched cyber security vouchers that can be used for

consultancy and labelling by certified companies.

The combination of these categories and tiers in

the label will give a clear overview for the SMEs situ-

ation and its context. This is the real challenge in the

galaxy of existing frameworks, recommendations and

ICISSP 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

430

controls. The label has to be smart and flexible, de-

signed and/or adapted for tight resources and budget.

A small bakery and a sensible data processing com-

pany do not have the same budget and are not con-

fronted to the same threats, the approach obviously

has to be tailored without sacrificing the security.

5 STATUS AND ROADMAP

The problematic surrounding cyber security in the

context of SMEs is real and not new. The standards

and frameworks were first designed with large com-

panies in mind as they were the biggest targets. As

these actors are now becoming tougher, the attacks

have shifted to smaller and more vulnerable targets:

SMEs. Current effort by governments to help them

is currently more driven by best effort than concrete

solutions. SMEs are by definition very heterogeneous

and a single solution can’t fit all, while classic stan-

dards and frameworks are not tailored for them. The

need for a comprehensive, flexible and cost-minded

framework is clear hence main actors such as Euro-

pean union and major standards are beginning to work

on it. There is space for a more local and close-to-the-

market approach to start the process with SMEs and

prepare them when the classic behemoths will begin

to issue recommendations and regulations.

After having outlined our approach and engaged

with the relevant IT cluster and our public authorities,

our work is now to collaboratively refine the practical

label organisation and conduct first labelling pilots.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was partly funded by the DIGITRANS

and IDEES research projects of the Walloon Region.

We thanks Infopole and companies of the cyber secu-

rity cluster for their support.

REFERENCES

Alex Whalen (2017). Digital europe’s views on

cybersecurity certification and labelling schemes.

http://bit.ly/2m3dyLV.

ANSSI (2014). France Cybersecurity Label.

https://www.francecybersecurity.fr.

Boateng, Y. and Osei, E. (2013). Cyber-Security Challenges

with SMEs. Developing Economies: Issues of Confi-

dentiality, Integrity & Availability, Aalborg Univ.

CIS (2016). CIS Controls V6.1. https://www.cisecurity.

org/controls.

CybSafe (2017). Enterprise IT leaders demanding more

stringent cyber security from suppliers. http://bit.do/

cybsafe.

Digital SME Alliance (2017). European Cyberse-

curity Strategy: Fostering the SME Ecosystem.

http://bit.do/digital-europe.

Donovan, S. (2016). Annual Report to Congress, Fed-

eral Information Security Modernization Act. Office

of Management and Budget http://bit.do/fisma-report-

15.

ENISA (2015). Information security and privacy standards

for SMEs. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/

standardisation-for-smes.

EU (2016). General data protection regulation. http://eur-

lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj.

EU (2016). Strengthening Europe’s Cyber Resilience Sys-

tem and Fostering a Competitive and Innovative Cy-

bersecurity Industry. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2016%3A410%3AFIN.

Eubanks, R. (2011). A Small Business No Budget Imple-

mentation of the SANS 20 Security Controls. SANS

Institute InfoSec Reading Room.

Hayes, J. and Bodhani, A. (2013). Cyber security: small

firms under fire [information technology professional-

ism]. Engineering Technology, 8(6):80–83.

ISSA (2011). 5173 Security Standard for SMEs.

http://www.wlan-defence.com/wp/ISSA-UK.pdf.

Leclair, J. (2015). Testimony of Dr. Jane Leclair before the

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Small

Business. http://bit.do/sme-leclair.

Lieberman, D. (2011). Practical advice for smbs to use iso

27001. http://www.infosecisland.com.

Muller, P. et al. (2015). Annual Report on European SMEs

2014/2015. European Commission.

NIST (2014). Cybersecurity Framework. https://www.nist.

gov/cyberframework.

Osborn, E., Creese, S., and Upton, D. (2015). Business vs

Technology: Sources of the Perceived Lack of Cyber

Security in SMEs. In Proc. of the 1st Int. Conf. on

Cyber Security for Sustainable Society.

Padfield, C. (2015). Issues of IT Governance and Informa-

tion Security from an SME & Social Enterprise Per-

spective. MSc Edinburgh Napier University.

Sage, O. (2015). Every Small Business Should Use the

NIST CSF. https://cyber-rx.com.

Slye, J. (2016). Federal cybersecurity incidents contin-

ued double-digit growth. http://bit.do/cybersecurity-

incidents.

Smith, M. (2016). Huge rise in hack attacks as cyber-

criminals target small businesses. http://bit.do/sme-

attack-rise.

Symantec (2017). 2017 Internet Security Threat Report.

https://www.symantec.com/security-center.

UK Government (2016). Cyber essentials. https://www.

cyberaware.gov.uk/cyberessentials.

Towards a Cyber Security Label for SMEs: A European Perspective

431