On the Use of Classroom Response Systems

as an Integral Part of the Classroom

Jalal Kawash

1

and Robert Collier

2

1

Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary, 2500 University Dr. NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

2

School of Computer Science, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Dr., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Keywords:

Classroom Response Systems, Student Engagement, Lecture Design.

Abstract:

Classroom response systems are a great technology for enhancing the student classroom experience, and in

recent years they have been shown to improve student engagement, aid in knowledge retention, and provide

crucial formative feedback for students and educators alike. Unfortunately, it has been suggested that the

use of a classroom response system may introduce learning obstructions as well, specifically by confusing

participants or distracting students from the material. The authors advocate for a full integration approach of

classroom response systems in post-secondary classrooms as a way to preserve the well established benefits

while removing the perceived dangers. Such a full integration make use of such systems, not merely as an

“accessory” to lectures, but as part of the lecture flow. This full integration allows educators to use classroom

response systems throughout the stages of a lecture, but it requires educators to design their lectures utilizing

and exploiting the full potential of a classroom response system. The authors’ experience with such an ap-

proach shows that students highly appreciate it, fully recognize its value, and believe that it enhances their

learning experience, all without the perceived threats of distraction or confusion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Classroom response systems (CRS) present an excel-

lent opportunity for instructors to integrate techno-

logy into the classroom, and it is widely recogni-

zed that these systems can improve student learning

and increase student engagement. With the arrival

of many new CRS that require only the now ubiqui-

tous smartphone for participation, it is easier than ever

to bring CRS into the classroom. Furthermore, with

class sizes increasing (due to budget constraints in

many educational institutions), finding creative met-

hods to increase student engagement and motivation

has become even more important. CRS represent a

potential solution - these systems facilitate student

participation and provide numerous formative feed-

back opportunities, students and educators alike. CRS

are typically used by posing a question to the entire

class and then using the system to record and com-

pile the solutions submitted by the participants. The

authors’ personal practice also exploits the element of

surprise; students need not know when a question will

be posed or what the question might entail.

Although the body of literature on CRS presents

results that support the use of CRS in the classroom,

there are some studies that maintain that the use of

CRS in the classroom can present a distraction or ot-

herwise be a barrier to student learning. The aut-

hors’ thesis is that if CRS are carefully woven into the

fabric of a course, these dangers can be eliminated.

Such careful integration requires the use of CRS as

an integral part of the lecture flow, rather than as sup-

plemental “accessory”. The authors believe that lectu-

res present several opportunities into which CRS can

be integrated. The systems can be used as a warm-up

exercise, a review of or bridge with a previous lecture,

an activity for introducing or reinforcing new mate-

rial, an opportunity for interaction and discussion, etc.

It is also worth noting that it is not necessary to in-

clude CRS questions at every stage - CRS need not be

overused in order to successfully integrate them into

the classroom.

The authors have successfully used CRS as an in-

tegral part of several different courses, at all levels of

an undergraduate program in computer science, on to-

pics ranging from operating system design and com-

puter architecture to discrete mathematics and intro-

ductory programming. The CRS questions the aut-

hors used were inseparable from the lecture plan and

flow, and the authors integrated these questions in a

38

Kawash, J. and Collier, R.

On the Use of Classroom Response Systems as an Integral Part of the Classroom.

DOI: 10.5220/0006668500380046

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 38-46

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

wide variety of approaches. The authors have iden-

tified ten different categories of questions (albeit not

mutually exclusive) that can each be used to design

more engaging and interactive lectures, regardless of

the classroom size, and with this paper the authors

will explore how this deep integration of CRS into the

classroom addresses many of the concerns that might

prevent other educators from doing the same.

The remainder of this paper is organized as fol-

lows. Section 2 discusses related work in the con-

text of the use of CRS. The categories of CRS que-

stions that the authors have identified are discussed

in Section 3 and an example CRS is discussed in

Section 4. Section 5 examines one of the authors’

courses (into which a CRS was integrated) and criti-

cally reflects on the student feedback that was recei-

ved. Section 6 reviews and concludes the paper.

2 RELATED WORK

Many educators first consider the inclusion of CRS

activities in their courses as opportunities to improve

student engagement, particularly in courses with very

large class sizes. This significant application notwit-

hstanding, CRS systems offer another, unique oppor-

tunity for formative feedback that can be generated

immediately, even in large populations. The feedback

provided by CRS can be used by students to discre-

tely self-assess themselves on a specific facet of a lar-

ger topic by comparing their own performance against

that of the rest of the class. Simultaneously, the in-

structor can review the performance of all participants

and assess how well the corresponding material has

been understood by the class, adjusting the pace of

the lecture to match the immediate learning needs of

the participants.

The effectiveness of CRS in delivering these in-

valuable opportunities is supported by several exten-

sive studies (Boscardin and Penuel, 2012; Moss and

Crowley, 2011; Kay and LeSage, 2009; Bruff, 2009;

Moredich and Moore, 2007), and nearly all of the sur-

veyed literature supports the claim that participants

are satisfied with the CRS activities themselves. That

said, on more than one occasion (Blasco-Arcas et al.,

2013; Webb and Carnaghan, 2006), it has been sugge-

sted that benefits attributed to CRS by these research

studies might simply be the result of improving inte-

ractivity in the classroom. Nevertheless, since CRS

represent an interactive activity that can be used with

a class of virtually any size, it is not unreasonable to

state that this application of CRS is almost universally

accepted. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that

CRS activity performance is a good predictor of over-

all performance (Porter et al., 2014), and that, with

no additional effort, CRS can be used to identify par-

ticipants that might be struggling (Liao et al., 2016).

Others (Porter and Simon, 2013; Simon et al., 2010)

also indicated that they used CRS as one of their best

practices for student retention.

The effective use of CRS has been shown to bene-

fit student performance as well. Simon et al. (2013)

contrasted the performance of students instructed tra-

ditionally against a peer-instructed offering, finding

that the peer-instructed subjects (that made extensive

use of CRS) outperformed those who were instructed

in a more traditional manner. Similarly, Steven Huss-

Lederman (2016) reported on a 2-year experiment in

which first-year students showed better learning gains

as a result of using a CRS. More recently, Collier

and Kawash (2017) presented quantitative evidence

that CRS questions can be structured and presented

in such a way as to improve a participants ability to

retain content, by allowing students to revisit content

that has already passed from short-term memory.

In contrast with these results, some studies have

suggested that the inclusion of CRS activities may not

yield any benefits and could in fact actually create a

barrier for some students. Robert Vinaja presented

(2014) the results of an experiment where the use of

a CRS (alongside recorded lectures, videos, and ot-

her electronic materials) did not result in a perfor-

mance improvement. In a broader criticism of in-

class discussion in general, Kay and Lesage (2009)

discussed how exposure to differing perspectives (that

could potentially arise during the discussion follo-

wing a CRS question) might cause confusion. Simi-

larly, Draper and Brown (2004) suggested that CRS

activities might distract students from their actual le-

arning outcomes.

Although those findings are not consistent with

the authors’ own experiences, CRS do require an in-

vestment (with respect to both lecture time and prepa-

ration time) and the concern that the activity might be

confusing or distracting cannot be summarily dismis-

sed. Nevertheless, the authors believe that the con-

cerns about CRS activities being disruptive or confu-

sing can be addressed by an integrated approach. The

authors conjecture that, when a CRS is carefully in-

tegrated into the classroom flow (as opposed to being

treated as a novel but disjoint activity) these potential

barriers will no longer exist.

On the Use of Classroom Response Systems as an Integral Part of the Classroom

39

3 CATEGORIZATION OF CRS

QUESTIONS

The exposure to a different perspective a student

might receive notwithstanding, for a CRS itself to be

considered confusing it would have to represent an

activity that was unfamiliar to the class. This concern

can be easily addressed by increasing the frequency

with which CRS activities appear in the classroom,

and since the investment associated with the use of

CRS can be weighed against the potential benefits

previous noted, the greatest barrier to an education

choosing to employ a CRS may be the perception

that the system itself might be a distraction. The

authors believe this concern can be addressed as

well, but in order to properly integrate CRS activities

in such a way as they are neither distracting nor

disruptive, it must first be recognized that a single

CRS activity can take many different forms and

address many different needs. By recognizing the

role of a question (and answering the question “what

do I expect to gain from this activity?” ) an educator

is able to integrate that question into the lecture such

that it will not present a distraction. To this end the

authors have established a collection of categories for

the different classes of questions that can be asked

using a CRS. It should be noted that these categories

are not necessarily mutually exclusive – an indivi-

dual question could belong to more than one category.

Ice Breakers: Ice breaker questions are intended to

change or influence the classroom social atmosphere

in a positive way. These are especially important in

the first lecture of a course but can be useful at ot-

her times as well. Icebreaker questions can be used

to address any stereotypes and misconceptions about

the course, the instructor, and the students themsel-

ves. In the authors’ respective courses, for instance,

the authors have used icebreaker questions to address

misconceptions about the difficulty of a subject or the

importance and relevance of a particular topic.

Being aware and addressing social dynamics

in the classroom is crucial. The use of power by

educators in learning environments necessitates

continued attention because it strongly influences

educator-student relationships, students’ motivation

to learn, and the extent to which learning goals are

met. Icebreaker questions can be used to reinforce

positive powers (such as reward and expert powers)

and avoid the use of negative powers (such as

coercive power).

Material Reinforcement / Content Retention:

Questions in this category typically include variations

of the material being discussed and directly apply the

content most recently presented to the students. The

interval between the delivery of the CRS question and

the presentation of the corresponding material can

determine how useful a question can be in improving

content retention. The most common practice is to

pose CRS questions during or immediately after the

presentation of the corresponding material and, in so

doing, the CRS question becomes a reinforcing acti-

vity (e.g., an additional example), albeit one where

student engagement is improved by transitioning

students from a passive recipient role into an active

participant role. Alternatively, this type of question

can be posed after a significant period of time

(typically at the beginning of the following lecture).

This interval entails that the relevant knowledge has

passed out of the short-term memory of the students,

and, as a result, the question becomes an opportunity

to revisit and review the corresponding content,

improving the likelihood that it will be retained.

Feedback: Questions in this category are designed

to provide immediate and formative feedback to the

students and/or the instructors. Students can use their

performance (relative to the other participants in the

class) to self-assess their knowledge in the topics

being presented, identify gaps that may exist in their

current understanding, and even respond immediately

to fill those gaps. With CRS systems that allow stu-

dents to revisit past questions outside of the lectures,

student can also review their performance over a par-

ticular set of questions, seeking out further resources

or assistance as warranted.

The feedback from a CRS activity can also be

important to the instructor, since it allows for the

immediate assessment of the understanding of the

class, providing information on whether and where

a specific subject needs reinforcement. If the class

(as a whole) under-performs on a particular question,

the instructor can respond immediately by providing

more examples or by approaching the subject from

different angles. Instructor feedback questions can

also help in identifying student pitfalls in certain

subjects, which can be invaluable in future course

development.

Bridging: Often the best way to transition between

one subject to another in the classroom is through a

problem or discussion and these transitions can be

accomplished using CRS questions. While students

may not score well on these questions (as they do

not reference specific material that has already been

presented), they provide an opportunity for students

to be challenged by thinking “outside the box” and/or

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

40

trying to relate different concepts together. These

bridging questions can be designed to motivate the

inclusion of the next topic in the course, while, at the

same time, relating it to the material most recently

presented.

Reflection: After a lecture, The authors often

challenge their students to apply their knowledge

using higher-level thinking problems. CRS questions

can be readily used at the end of a lecture, where

the questions are discussed and left with students as

homework to answer until the following lecture.

Review: The use of CRS questions in review ses-

sions can make these sessions more engaging and

beneficial to students. The authors were able to

organize review sessions that required little or no

lecturing, and these sessions were highly welcomed

by the students. The authors would typically provide

students with a practice set of problems in advance

and then, during the review session, the students were

given a series of quizzes (to be completed in small

groups). Each of these quizzes ended in at least one

CRS question, testing certain critical aspects of that

particular quiz.

Fun Injection: Fun injection is a common technique

used to keep a relaxed atmosphere in the classroom,

balance the serious tone of the lectures, and give

the students the opportunity to stay engaged. CRS

questions can be used to occasionally inject fun

and these questions need not be orthogonal to the

lecture (i.e., there need not be an abrupt transition

from a serious topic into a fun injection question).

As a clarifying example, a multiple-choice question

for which all of the answers are correct can spark

an engaging and entertaining discussion, while still

focussing on the corresponding material! It should

be noted that a question from virtually any other

category can be restructured such that it belongs to

the fun injection category as well.

Polling: Since most CRS questions can be configured

such that the collection of responses can be reviewed

anonymously, students can participate in polls to

assess their learning, preferred delivery styles, etc.

without discomfort. Polling students on the pacing

of the lectures or the difficulty of the exams, for

instance, can grant students a safe way to voice their

concerns without sacrificing the feedback for the

instructors.

Attendance: It is worth noting that, in institutions

or settings where attendance is a requirement, atten-

dance questions can be easily incorporated into CRS,

avoiding the overhead associated with keeping an

attendance tally at the beginning of every lecture.

Series: While some may argue that the nature of

CRS does not allow working on complex problems

and thorough problem-solving techniques, the aut-

hors have used CRS to solve complex problems by

presenting them as a series of interrelated questions.

The step-by-step solution to a complex problem can

be converted to a relevant series of CRS questions

that will ultimately form a complete solution to the

problem. This is, in fact, a very practical and ef-

fective approach for teaching students the “divide-

and-conquer” problem solving technique.

4 EXAMPLE CRS: “Tophat”

There are a number of different CRS solutions avai-

lable for instructors seeking to include this activity in

their courses. Different solutions offer different fea-

tures (in terms of data collection, statistics, learning

management system integration, etc.) but many of

the most recently introduced options allow students

to respond with laptops or smartphones (eliminating

the need for a separate dedicated “clicker” device).

For this paper, the authors have decided to present re-

sults from a course into which the Tophat classroom

response had been integrated, and the authors’ expe-

rience shows that most students (by far) prefer to in-

teract with this system using their smartphone and a

mobile app.

The initial interaction point with Tophat is the

Web site www.tophat.com. Users (students and in-

structors) create accounts and, as a part of a user pro-

file, specify a mobile phone number if the user would

like to exploit a text messaging interaction method

with the system. Instructors can further organize their

Tophat account into separate courses. Once a course

is created, invitations can be broadcast to populations

of students to allow them to join the course. Tophat

also has a mechanism to automatically synchronize

with class lists on some learning management systems

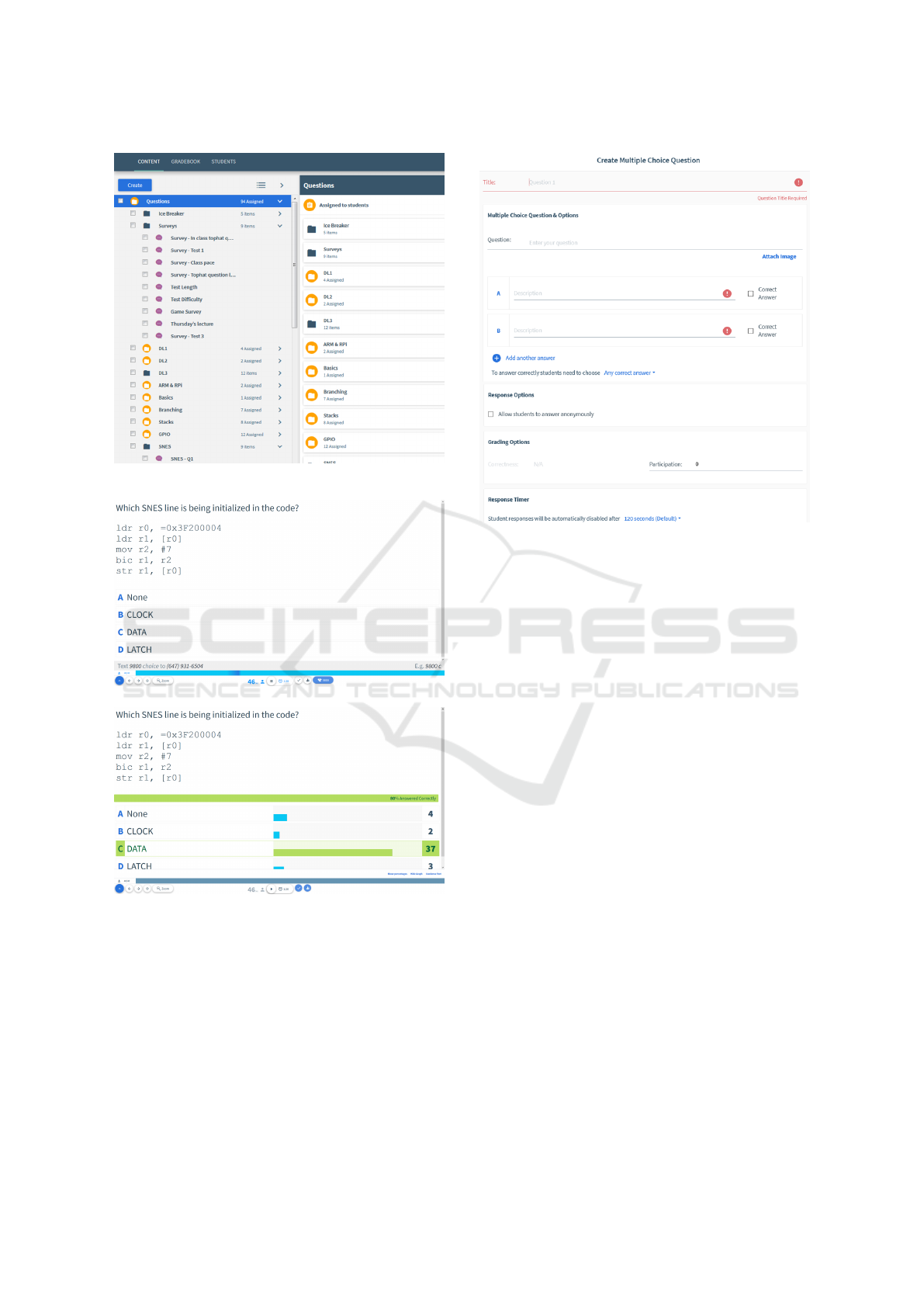

(LMS). Figure 1 shows the main course screen for an

example course in Tophat.

Figure 2(a) shows an example CRS question as it

appears to students; Figure 2(b) also shows the ques-

tion the class response statistics screen with the high-

lighted correct answer.

Each course has three main areas:

• Content: where questions and other content are

created

On the Use of Classroom Response Systems as an Integral Part of the Classroom

41

Figure 1: Main course screen in Tophat.

(a)

(b)

Figure 2: Asking a question in Tophat (a) Question screen

(b) Class responses and correct answer.

• Gradebook: a database of student activity regar-

ding answering questions. This activity can be do-

wnloaded as a spreadsheet or synchronized with

student records on a LMS.

• Students: A list of enrolled students and a mecha-

nism to invite more students

Submissions can be evaluated using a combina-

tion of participation and correctness, with the instruc-

Figure 3: Creating a multiple-choice question in Tophat.

tor also specifying the relative weight of each ques-

tion and the relative weights of the participation and

correctness components. Instructors can also specify

the duration of the question (with students being al-

lowed to submit and re-submit their answers as many

times as they wish while the question is active).

Many modern CRS offer a variety of question

types, taking full advantage of the different ways

a participant can interact with their smartphone or

laptop computer. For the Tophat CRS, there are six

question formats that can be created:

Multiple-Choice: Although the practices (and best

practices) associated with multiple-choice item

creation is a topic that is actively and thoroughly

investigated, Tophat allows instructors to pose any

type or question (supported by imagery if neces-

sary) with any number of possible answers and no

restrictions on how many answers can be considered

correct. It is the authors’ suspicion that this is the

most commonly used question format, both for the

simplicity with which they can be constructed and

the existing familiarity many students already have

with multiple-choice questions.

Word Answer: This is typically used for questions

that require a single word or a short phrase response.

Although the fact that the student must generate

a response (and not just select it from a list of

options) may be interpreted as a positive aspect, an

unfortunate shortcoming is that student answers that

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

42

do not conform to the expected “model solution”

might not be considered correct.

Numeric Answer: A numeric answer question

requires students to enter a single number as a

response. While obviously very useful for testing a

students ability to complete accurate calculations,

the instructor can specify a tolerance range to make

questions for other areas as well. As a clarifying

example, a tolerance of 1 and a correct answer of

50 would mean the values 49, 50, and 51 would all

be accepted as correct, making this question type

suitable for asking students to estimate a particular

time-frame, value, or statistic.

Matching: For this format the instructor specifies a

list of ordered pairs (e.g., corresponding elements,

numerical values, etc.) and Tophat shuffles the

elements before presenting. It is then the task of

the students to reassemble each ordered pair. Figure

4 shows an example matching question with more

responses than premises.

Sorting: Similar to the matching format above, for

this format the instructor provides a sorted list of

items that is shuffled before presentation. Students

are then expected to resort the elements of the list

before proceeding. Figure 5 shows an example

sorting question.

Click-on-Target: For these questions an image is

uploaded and students click on certain parts of the

image. The system would then track where each of

the students clicked.

It is worth noting that the wide variety of ques-

tion types is potentially useful for ensuring a learner-

centered approach, because students of different lear-

ning styles may find some types of questions easier

to process (and thus more useful) that others. Were

verbal learners, for instance, may be well-served by

a body of multiple-choice questions, visual learners

might be better served by questions with the matching

or click-on-target styles.

Tophat has also other features such as discussion

forums and a space for uploading slides and files.

These are beyond the scope of this paper.

5 STUDENT FEEDBACK

Both authors of this paper have used CRS as an inte-

gral part of most of their courses, and in the authors’

experiences, it was only rarely encountered that CRS

were distracting, confusing, or unhelpful. Although

(a)

(b)

Figure 4: A matching question in Tophat (a) Creating the

question (b) Students’ view.

Figure 5: A sorting question in Tophat.

it is not unusual for a student to become confused by

a particular question (which is obviously something

that can occur regardless of how the question was pre-

sented) it is virtually always confusion surrounding

the material, and not the interface to the CRS. Furt-

hermore, since the authors integrate CRS into their

courses very early in the semester, the activity beco-

mes a familiar component of the classroom and is not

typically considered a distraction.

In supporting the authors’ claims that an integra-

ted approach addresses concerns about confusion and

distraction, this section presents data collected from

one of the authors’ courses into which CRS was fully

integrated. This is a second-year, required course in

Computer Science dealing with computer architecture

and low-level programming. This data was collected

over a period of two years from 2015 to 2016 and in-

volved 292 surveyed students - a survey participation

On the Use of Classroom Response Systems as an Integral Part of the Classroom

43

Figure 6: Summary of student feedback.

rate of 64%. During this 2-year period, the course

was offered six times: four offerings during regular

terms (one offering per term) and two accelerated of-

ferings in during summer terms. The total number of

students registered in this course during that period

was 459, with class sizes ranging between 43 and 131

students. All offerings of the course during this pe-

riod were taught by the same instructor and Tophat

was integrated into all the lectures in every offerings.

Students voluntarily participate in anonymous sur-

veys required by the university at the end of each

term. In these surveys, students were asked about

what the instructor did to help their learning and were

given the chance to name one aspect that was especi-

ally effective in supporting their learning. No options

were presented to the students - the question was en-

tirely free-form. 292 valid surveys were received and

an overwhelming 77% of the surveyed students men-

tioned CRS (specifically, Tophat) as the most effective

aspect in the course that helped their learning. The

remaining 33% mentioned visual aids used by the in-

structor, group work activities, open-book exams, and

the lab assignments. Figure 6 clearly shows that the

CRS dominated the survey participant responses con-

cerning especially effective supports for each of the

six semesters (which have been arranging according

to class size, from lowest to highest).

The authors should note that in Canadian univer-

sities, the Fall semester spans September to Decem-

ber, the Winter Semester covers January to April, and

the Spring semester consists of May and June (there is

also a second short Summer semester in July-August.)

A full table of the values used to create the pre-

vious chart is presented in Table 1. In this table, the

Table 1: Student feedback details.

Semester Course Survey Participants

Enrollment Participants citing CRS

Specifically

Winter 120 79 58

2015 (73.4%)

Spring 43 33 26

2015 (78.8%)

Fall 50 35 30

2015 (86%)

Winter 131 89 68

2016 (76%)

Spring 45 25 19

2016 (76%)

Fall 70 33 26

2016 (79%)

Total 459 292 224

(77%)

rows correspond to the semesters (listed in chronolo-

gical order) and each row shows the class size, num-

ber of students participating in the survey, and the

number of survey participants mentioning the CRS as

an effective learning support. The fact that the num-

ber of students that mentioned CRS specifically ne-

ver dropped below 73% of the total number of survey

participants is a testament to how well the CRS was

integrated into this course.

The surveys also included questions where partici-

pants could specify what they believe should be chan-

ged in order to improve future offerings. Only 2 out

of the 292 survey participants complained about the

CRS - one student considered it to be a distraction,

and the other, while openly recognizing the value of

CRS, believed the number of CRS questions presen-

ted could be reduced. This means that less than 0.35%

of the participants considered the use of a CRS as

a distraction, in stark contrast with some of the ear-

lier studies mentioned in Section 2. Furthermore, less

than 0.70% of the subjects had anything negative to

say about the use of CRS. The authors attribute this

overwhelming positive response to the fact that the in-

tegrated approach has made the activity familiar and

non-disruptive, without sacrificing its effectiveness as

an engagement and feedback tool. Digging deeper

into the student free-form written comments, many

students thought the use of Tophat CRS was engaging.

As one student put it:

“Tophat kept me motivated to come to class

and made the class fun.”

The students also praised the usage of the CRS

for its ability to reinforce the material. Some of the

student comments included:

“Tophat clarified confusing concepts.”

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

44

“Tophat cements the knowledge in your

head.”

“The Tophat questions worked great and

help ensure you actually understood what you

though you understood.”

It is obvious from these comments that well-

crafted questions, when properly integrated into the

lectures, can help alleviate the illusion of understan-

ding and deal with learning uncertainties by providing

an opportunity to practice material and receive imme-

diate, formative feedback. Other participants added:

“Tophat ironed out pretty much all mid-

lecture uncertainties.”

“The feedback from the Tophat questions al-

lowed you to adjust your focus to areas of

need.”

Properly integrated questions can help the instruc-

tor better explain difficult concepts, by deconstructing

the problem into smaller pieces and giving the stu-

dents the chance to actively work on these problems,

rather than turning the students to passive recipients

of information. In support of this claim, the authors

received the following participant comments:

“Tophat was particularly helpful in under-

standing tricky concepts.”

“Tophat questions were very effective in pro-

viding a chance for students to try out new

concepts.”

“The Tophat questions basically forced you

to focus and apply the knowledge.”

It is clear that many of these comments echo the

well-established benefits associated with the use of

CRS. The authors also believe that the results of this

two-year investigation provide strong support to the

claim that a full integration of CRS into the classroom

addresses virtually every concern an instructor might

have about adding CRS to their own courses. Alt-

hough effective CRS integration represents the same

kind of investment of time and effort that would be ex-

pected of any best practice, the authors believe this in-

vestigation has clearly demonstrated that the barriers

can be addressed without sacrificing any of the bene-

fits.

6 CONCLUSION

The use of CRS in the classroom has been proven to

be beneficial to students since it improves their lear-

ning experience in general. The authors advocate for

a classroom within which a CRS is fully integrated

into the lecture plan. In such a classroom, CRS is

not a superfluous accessory to the lecture, but an in-

tegral part of it — CRS is used to warm-up, bridge,

introduce, reinforce, and review material throughout

the entire course. In this paper, the authors have pro-

posed a collection of categories for the different CRS

questions that the authors believe clarifies how these

activities can be fully integrated. The authors have

also discussed a well-known CRS system, called Top-

hat, exploring how it can be effectively used as more

than just a supplementary activity. Finally, the aut-

hors have shared feedback, collected from hundreds

of students subjected to this integrated CRS appro-

ach, over 6 offerings of a single course over the pe-

riod of 2 years. This feedback overwhelmingly sup-

ports the claim that CRS, more than any of the many

other activities, was the most effective feature that en-

hanced student learning. Only a single student from a

population of 292 considered CRS to be a distraction

for learning, so the authors believe that the call for

the full integration of CRS will obliterate the percei-

ved dangers associated with their introduction into the

classroom.

REFERENCES

Blasco-Arcas, L., Buil, I., Hernandez-Ortega, B., and Sese,

F. J. (2013). Using clickers in class. the role of in-

teractivity, active collaborative learning and engage-

ment in learning performance. Computers & Educa-

tion, 62:102–110.

Boscardin, C. and Penuel, W. (2012). Exploring benefits of

audience-response systems on learning: a review of

the literature. Academic Psychiatry, 36(5):401–407.

Bruff, D. (2009). Teaching with Classroom Response

Systems: Creating Active Learning Environments.

Jossey-Bass.

Collier, R. D. and Kawash, J. (2017). Improving student

content retention using a classroom response system.

In CSEDU 2017 - Proceedings of the 9th Internati-

onal Conference on Computer Supported Education,

Volume 1, Porto, Portugal, April 21-23, 2017., pages

17–24.

Draper, S. W. and Brown, I. M. (2004). Increasing inte-

ractivity in lectures using an electronic voting system.

Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 20:81–94.

Huss-Lederman, S. (2016). The impact on student learning

and satisfaction when a cs2 course became interactive

(abstract only). In Proceedings of the 47th ACM

Technical Symposium on Computing Science Educa-

tion, SIGCSE ’16, pages 687–687, New York, NY,

USA. ACM.

Kay, R. H. and LeSage, A. (2009). Examining the benefits

and challenges of using audience response systems:

On the Use of Classroom Response Systems as an Integral Part of the Classroom

45

A review of the literature. Computers & Education,

53(3):819–827.

Liao, S. N., Zingaro, D., Laurenzano, M. A., Griswold,

W. G., and Porter, L. (2016). Lightweight, early iden-

tification of at-risk cs1 students. In Proceedings of

the 2016 ACM Conference on International Compu-

ting Education Research, ICER’16, pages 123–131,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Moredich, C. and Moore, E. (2007). Engaging students

through the use of classroom response systems. Nurse

Education, 32(3):113–116.

Moss, K. and Crowley, M. (2011). Effective learning in

science: The use of personal response systems with

a wide range of audiences. Computers & Education,

56(1):36–43.

Porter, L. and Simon, B. (2013). Retaining nearly one-third

more majors with a trio of instructional best practi-

ces in cs1. In Proceeding of the 44th ACM Technical

Symposium on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE

’13, pages 165–170, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Porter, L., Zingaro, D., and Lister, R. (2014). Predicting stu-

dent success using fine grain clicker data. In Procee-

dings of the Tenth Annual Conference on International

Computing Education Research, ICER ’14, pages 51–

58, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Simon, B., Kinnunen, P., Porter, L., and Zazkis, D. (2010).

Experience report: Cs1 for majors with media com-

putation. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Con-

ference on Innovation and Technology in Computer

Science Education, ITiCSE ’10, pages 214–218, New

York, NY, USA. ACM.

Simon, B., Parris, J., and Spacco, J. (2013). How we teach

impacts student learning: Peer instruction vs. lecture

in cs0. In Proceeding of the 44th ACM Technical Sym-

posium on Computer Science Education, SIGCSE ’13,

pages 41–46, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Vinaja, R. (2014). The use of lecture videos, ebooks, and

clickers in computer courses. J. Comput. Sci. Coll.,

30(2):23–32.

Webb, A. and Carnaghan, C. (2006). Investigating the

effects of group response systems on student satis-

faction, learning and engagement in accounting edu-

cation. Issues in Accounting Education, 22(3).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

46