Internet Interventions for Family Caregivers of People with

Neurocognitive Disorder

A Literature Review

Audrey Duceppe, Caroline Camateros and Jean Vézina

Department of Psychology, Laval University, 2325 allée des bilbiothèques, Quebec, Canada

Keywords: Family Caregiver, Dementia, Neurocognitive Disorder, Internet, Technology, Web, Literature Review.

Abstract: Taking care of a loved one can be a new, yet challenging role for caregivers. However, these caregivers are

usually overbooked and do not have the time needed to reach for help. Internet interventions are a great way

to offer psychoeducation, support and tools for caregivers, in the comfort of their home. This literature review

explores the impact of internet intervention programs. Twenty-two studies were found in PsychNet, Medline

and Google scholar using "family caregiver, dementia, neurocognitive disorder, internet, technology, web" as

keywords. A review of these studies showed that internet intervention for caregivers have an impact on the

caregiver’s psychological health (e.g. feeling of burden, stress, depression, anxiety, etc.), on their relation to

the care receiver (reaction to disruptive behaviors, self efficacy, positive aspects of caregiving, better

understanding of the illness, etc.) and even of the care receiver himself (disruptive behaviors occurrence and

severity). However, internet intervention programs for caregivers show a great versatility in their effectivity

results, but they still appear to be a good way to provide psychoeducation on neurocognitive disorder, to

reduce negative emotion associated with caregiving and improve the caregiving relationship itself.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is well-known that caring for a loved one affected

by a neurocognitive disorder can lead to negative

consequences for the caregiver, such as a feeling of

burden (Glueckauf, Ketterson, Loomis and Dages,

2004; Griffiths, Whitney, Kovaleva and Hepburn,

2016; Lorig et al., 2016), depression (Blom, Zarit,

Groot Zwaaftink, Cuijpers and Pot, 2015; Griffiths et

al., 2016) and anxiety (Beauchamp, Irvine, Seeley,

and Johnson, 2005; Griffiths et al., 2016). Caregivers

often feel lost and overwhelmed with this new role

(Collins and Swartz, 2011). In addition to memory

and functional loss associated with neurocognitive

disorder, caregivers also have to deal with disruptive

behavior like aggression, agitation, wandering, etc.

(Kamiya, Sakurai, Ogama, Maki and Toba, 2014).

These behaviors appear to be the most distressing for

caregivers, contributing to the feeling of burden and

depression symptoms (e.g. Brodaty Woodward,

Boundy, Ames, Balshaw and PRIME Study Group,

2014; Kamiya et al., 2014).

Many interventions type exist to reduce the

burden of care, like respite, support groups or

psychoeducation or internet intervention programs.

Interventions designed for caregivers have multiple

benefits. In addition to improving the caregiver’s

well-being, this kind of intervention can help them

offer a better care for their loved one and delay their

institutionalization, which is very costly in terms of

quality of life and healthcare costs (Keefe and

Manning, 2005). In this sense, these positive

outcomes are not limited to the caregivers and their

loved one, but also offer an economic and

personalized solution for society (Åkerborg et al.,

2016; Keefe and Manning, 2005).

Among all intervention aimed to reduce negative

consequences of caregiving, internet intervention

programs appear to be the ones most suited for the

caregiver’s reality. In fact, with all the tasks and

responsibilities associated with care, caregivers often

do not have the time needed to seek for help. The lack

of accessibility of interventions is an obstacle to the

participation of caregivers. One study reported that up

to 60% of caregivers contacted for an intervention

refused to participate because of the time required

(Wiprzycka, Mackenzie, Khatri, and Cheng, 2011).

With internet intervention, they have the

opportunity to choose the service and use it at their

96

Duceppe, A., Camateros, C. and Vézina, J.

Internet Interventions for Family Caregivers of People with Neurocognitive Disorder.

DOI: 10.5220/0006671700960102

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2018), pages 96-102

ISBN: 978-989-758-299-8

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

suitability. Internet interventions reduce time travel,

they are adapted to the caregiver schedule and allow

caregivers to select the types of services they need

(Blom, Bosmans, Cuijpers, Zarit, and Pot, 2013).

Studies show that the majority of participants are

comfortable with computers and appreciate their

virtual participation in the group. The majority of

participants say the web sessions are comparable to

traditional face-to-face meetings and would recom-

mend the intervention to their friends (Chiu et al.,

2009; Finkel et al., 2007).

Despite the ease of access to internet

interventions, recent studies show conflicting results

on the efficacy of these programs. This article

proposes a review of the literature of the

characteristics of internet intervention programs and

their impacts on caregivers. This article may help

researchers in creating effective internet interventions

for caregivers. Clinicians seeking evidence on which

to build treatment may also draw on the findings of

this article.

2 METHOD

The search for this review was made mainly though

PsychNet Medline and Google Scholar. We used

"family caregiver, dementia, neurocognitive disorder,

the internet, technology, web" as keywords. These are

the combinations used: Family caregivers, dementia,

and technology; family caregivers, dementia and

internet, family caregivers, dementia and web-

conference; family caregivers, intervention, dementia

and internet. The snowball method was used to

identify articles from the reference list of articles

already included in the review.

2.1 Inclusion Criteria

The selected studies needed to be aimed at family

caregivers of individuals affected by a major

neurocognitive disorder and use computers to offer an

intervention program. They also had to be written in

French or English.

There was no limit on the age of articles, however,

articles were closely analyzed to ensure their

technological methods were still relevant, for

example a study using videophones or VHS was

excluded (studies using smartphones were

included).

2.2 Exclusion Criteria

Studies with no use of computers (traditional face-to-

face meetings or telephone calls), studies that

included caregivers of all older adults with no

specification concerning the presence of major

neurocognitive disorder were excluded. We also

excluded studies with attrition superior to 45% were

excluded.

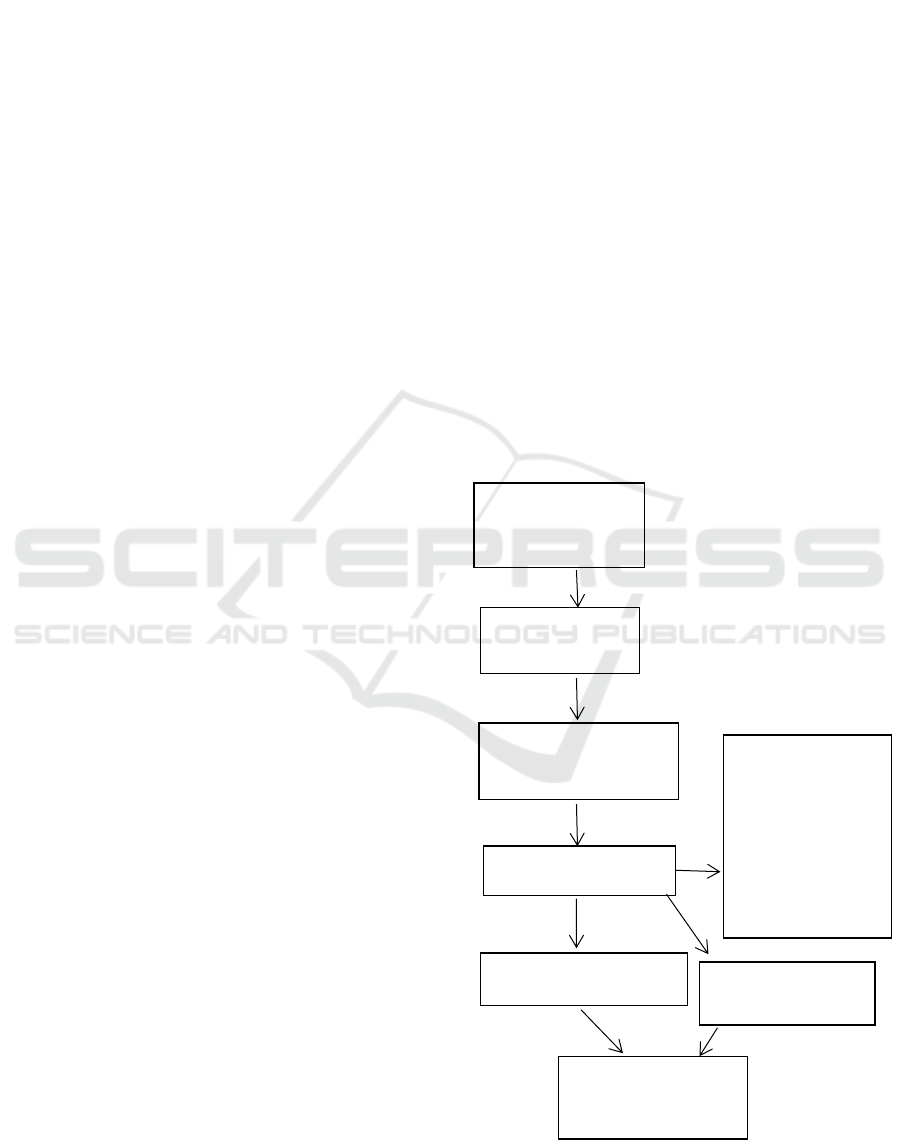

2.3 Selection of the Studies

When we searched through the databases,

1725 articles were found. There were 1096 articles

left after removing duplicates. Then, 574 articles were

excluded after reading the title and abstract.

Among the 55 articles fully red, 36 papers were

excluded because they did not meet the inclusion

criteria or covered additional facets of studies already

included in the review. In the end, 19 articles were

selected from a database and three more were added

from the articles reference list, for a total of 22

articles.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of article selection process.

1725 papers found

in initial searches

1096 duplicates

removed

574 excluded after title

and abstract were read

.

55 papers read in full

19 papers were eligible

3 papers added from

reference lists

22 papers were

included in the review

36 papers were

excluded because

they did not meet

inclusion criteria

or covered

additional facets of

studies already

included in review.

Internet Interventions for Family Caregivers of People with Neurocognitive Disorder

97

2.4 Studies’ Description

We identified 22 studies of internet intervention for

caregivers of a person affected by a neurocognitive

disorder. These studies were published between 1995

and 2017. These studies are specific to internet

intervention programs designed to reduce the

negative impact of caring, improve the caregiving

relationship or reduce the disruptive behaviors. The

passive intervention includes a website, video capsule

or for psychoeducation. Interventions could also be

active like group meetings by web conference

forums, emails or even web support groups to

encourage communication between caregivers or

caregivers and resources. Certain studies may include

multiple intervention types (Bass, Mcclendon,

Brennan, and Mccarthy, 1998; Blom et al., 2015;

Boots, de Vugt, Withagen, Kempen and Verhey,

2016; Chiu et al., 2009; Glueckauf et al., 2004 ;

Kelly, 2003; Lai, Wong, Liu, Lui, Chan and Yap.,

2013; Lorig et al., 2010; Marziali, Damianakis and

Donahue, 2006)

In this sample, twelve studies used a randomized

protocol, eight had a pre-experimental protocol (of

which three are pilot studies), one used a qualitative

methodology (O'Connell et al., 2014) and an other

used a mixted method (Kelly 2003). Control groups

included routine care (Cristancho-Lacroix, Wrobel,

Cantegreil-Kallen, Dub, Rouquette and Rigaud,

2015; van der Roest, Meiland, Jonker and Dröes,

2010), waiting lists (Beauchamp et al., 2005) leaflets

with various information (Blom et al., 2015; Finkel et

al., 2007, Hicken, Daniel, Luptak, Grant, Kilian and

Rupper, 2016; Lai et al., 2013; Marziali and Garcia,

2011) and a placebo website (Brennan, Moore, and

Smyth, 1995). Sample sizes of intervention groups

varied widely from 3 (Lai et al., 2013) to 700 (Kelly,

2003) with an average of 71,36 caregivers. The

control groups, meanwhile, had an average of 57,15

caregivers (8 to 149). Attrition also varied from 0%

(Torkamani et al., 2014) to 41% (Boots et al., 2016),

with a mean of 19.4%. Attrition was not mentioned in

four of the 22 studies.

Where possible, studies were compared using the

effect sizes (Cohen's d). Among the randomized

studies, this was done with the following formula

(mean of post-test control group - mean of the

experimental group at post-test) / common standard

deviation. For single-group protocols, the following

formula was used; (mean pre-test - mean post-test) /

common standard deviation.)

3 RESULTS

3.1 Intervention’s Modality

Most aid programs used several modalities to reach

caregivers. The most popular method was the

interactive website, used in 18 studies. In general,

websites were used to facilitate psychoeducation and

participants visit the site individually, where

appropriate. The material was accessible for 6 weeks

(Lorig et al., 2010) and one year (Bass et al., 1998;

Brennan et al., 1995), depending on the study. Web

sites generally offered information on neurocognitive

disorder and on various care skills. In addition, some

offered more specialized tools, for example, to

facilitate decision-making (Brennan et al., 1995), to

help the caregiver better identify their needs (van der

Roest et al., 2010) or to teach emotional management

strategies (Beauchamp et al., 2005).

Seven authors pointed out that some of the

material was presented via video capsules

(Beauchamp et al., 2005; Glueckauf et al., 2004;

Griffiths, Whitney, Kovaleva and Hepburn, 2016;

Hicken et al., 2016; Jajor et al., 2016; Kajiyama et al.,

2013; Lorig et al., 2010; Torkamani et al., 2014).

Sometimes, asynchronous communication modalities

were also added to the website to encourage sharing

between caregivers. A forum or the option to

communicate with other participants via emails was

present on 12 websites (Bass et al., 1998; Brennan et

al., 1995, Blom et al., 2015; Boots et al., 2016;

Glueckauf et al., 2004; Jajor et al., 2016; Kelly, 2003;

Lai et al., 2013; Lorig et al., 2010; Marziali et al.,

2006; O'Connor, Arizmendi et Kaszniak, 2014;

Torkamani et al., 2014). With the use of email

between the participant and a health professional, the

studies of Chiu et al. (2009) and Kwok et al. (2014)

also provided individual psychotherapy sessions at a

distance. Finally, the assistance program of Marziali

et al. (2006) included 12 group meetings with web

conference to encourage social support. The 4 studies

that do not use a website offered psychoeducation via

audio conferences (Finkel et al., 2007) and web

conferencing (Griffiths et al., 2016) or social support

groups via audio conferencing (O'Connell et al.,

2014) or with a virtual reality tool (O'Connor et al.,

2014). These authors emphasized that these modes of

communication are synchronous, which facilitates

exchanges between the participants.

Overall, the majority of studies offered complex

assistance programs that address a variety of needs

and use several modalities. Their results were mixed.

As noted in Boots, Vugt, van Knippenberg, Kempen,

and Verhey (2014), it is difficult to interpret the

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

98

specific effects of each study since the characteristics

of the programs are not always well detailed. In

addition, data on usage rates and adhesion are rare.

Some of the findings from the meta-analyzes of

traditional caregiver programs can still inform

programs remotely. For example, it appeared that the

studies which target specific difficulties also have

encouraging results when offered at a distance. In

fact, the aid program of Glueckauf et al. (2004), by

web site and audio conference, led to significant

changes in perceived personal effectiveness for

different caring activities.

3.2 Intervention’s Utilization

Among the studies included in this review, 10 offered

information on participation rate or rates of use. In

synchronized interventions, the numbers of sessions

attended are one way to convey participation rate. For

example, in Finkel and colleagues’ study, 94% of

participants attended 7 or more out of a possibility of

8 sessions (2007). An other study also mentions high

participation rates but fail to provide them (O'Connell

et al., 2014) . Web site based programs reported using

in different ways. Some authors report the number of

visits; websites were consulted on average between

5.14 and 6.98 times per month (Bass et al., 1998;

Kajiyama et al., 2013; van der Roest et al., 2010).

Others report the average amount of time spent

consulting the web-site, they ranged from 14:36 min

to 106.41 minutes (Bass et al., 1998; Beauchamp et

al., 2005; van der Roest et al., 2010). The number of

modules or sessions completed are also reported, they

ranged from 70 to 83% of participants completing

sections (Cristancho-Lacroix et al., 2015). Finally,

studies with forums did report the number of posts by

participants, with a mean of 36.9 (Lorig et al., 2010).

3.3 Intervention’s Content

The intervention’s structure was missing in most of

the studies and protocol’s description was missing in

all of the studies. Therefore, some studies shared the

themes discussed in their intervention.

Most studies included an educational theme on

neurocognitive illness and/or caregiving role (e.g.

Bass et al., 1998; Beauchamp et al., 2005; Blom et al.,

2013; Brennan et al., 1995; Chiu et al., 2009;

Cristancho-Lacroix et al., 2015; Glueckauf et al.,

2016; Griffith et al., 2016; Hockem et al., 2016;

Kajiyama et al., 2013; Kwok et al., 2014; Lorig et al.,

2010; O’Connell et al., 2014; O’Connor et al., 2014).

Many studies also added problem solving skills or

decision-making, especially oriented towards

behavioral problems (Blom et al., 2013; Cristancho-

Lacroix et al., 2015; Kajiyama et al., 2013; Kwok et

al., 2014; Lorig et al., 2010), daily difficulties

(Beauchamp et al., 2005; Brennan et al., 1995; Chiu

et al., 2009; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., 2015) or to

enhance communication with the care receiver (Blom

et al., 2013; Hicken et al., 2016). Dealing with

emotions or even their care receiver’s emotions were

frequent themes too (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Chiu et

al., 2009; Hicken et al., 2016; Kajiyama et al., 2013;

Lorig et al., 2010). Some studies added a self-care

theme (Griffith et al., 2016; Hicken et al., 2016;

Kajiyama et al., 2013), which could contain sleeping

habits, alimentation habits (Lorig et al., 2010),

pleasant activities (Kajiyama et al., 2013) and

physical exercise (Lorig et al., 2010). Three studies

included information and exercises about relaxation

(Blom et al., 2013; Hicken et al., 2016; Kajiyama et

al., 2013). Planning the future also seemed to be a

recurrent theme (Kajiyama et al., 2013; Lorig et al.,

2010). In addition to these more frequent themes,

some studies included education or discussion on

seeking help (Blom et al., 2013; Cristancho-Lacroix

et al., 2015; Lorig et al., 2010), respite (Cristancho-

Lacroix et al., 20015), social and\or financial support

(Cristancho-Lacroix et al., 2015), pharmacotherapy,

non-pharmacotherapy and avoiding falls (Cristancho-

Lacroix et al., 2015).

Finally, most studies included emotional support,

by other caregivers or by health professionals, which

emerges to be central for caregivers, (Hicken et al.,

2016; Kajiyama et al., 2013) even when the study’s

results were inconclusive. This support could be

offered by email (Chiu et al., 2009) or telephone

(Hicken et al., 2016). One study also mentioned that

participants needed more dynamic interactions

(Cristancho-Lacroix et al., 2015).

Even though most studies showed great

acceptability of the internet format, one study showed

that man might have more positive feedback for

online intervention than women (Cristancho-Lacroix

et al., 2015). Furthermore, Bass and colleagues found

that online intervention is more effective if the

caregiver has a larger informal support network is

caring for a spouse or did not live alone with the care

receiver (1998), supposing that isolation might an

important issue for caregivers. In Kajiyama and

collegues’ study, caregivers mentioned they would

need more contacts with other caregivers and the

health professionals (2014).

Internet Interventions for Family Caregivers of People with Neurocognitive Disorder

99

3.4 Effect of Internet Interventions

Variables used to measure the effectiveness of aid

programs are also varied. These studies measured one

or many of those variables: feeling of burden,

depression, anxiety, stress, self-efficacy, fatigue,

distress, ability to reach objectives, confidence in

decision, ability to ask for help, positive aspects of

caregiving, perception of caregiving, occurrence and

severity of disruptive behaviors, reaction to disruptive

behaviors and distress related to disruptive behaviors.

Significant results were obtained in 12 of the 21

quantitative studies.

Three out of 12 studies (25%) identified a

significant reduction in the emotional burden, 60% (3

out of 5) decreased stress, 25% (3 out of 12)

decreased depressive symptoms, 100% anxiety (3 out

of 3), 67% (4 out of 6) showed an increase in self-

efficacy, 50% (3 out of 6) showed a decrease of the

disruptive behaviors and 33% showed a decrease of

the caregiver’s reaction to disruptive behaviors (1 out

of 3). Beauchamp et al. (2005) also reported a

significant increase in the intention to seek help and

positive aspects of caregiving, while (Brennan et al.,

1995) obtain an increase in confidence in decision-

making. (Boots et al., 2016) reported that caregivers

increased their achievement of goals. (Van der Roest

et al., 2010) have also reported an increase in

perceived competence in their sample.

When the intervention had a significant effect on

caregivers, Cohen’s d were calculated to ease the

comparison of studies. Caregiver’s feeling of burden

is a recurrent variable. In three studies found Cohen’s

d between 0.43 (Griffiths et al., 2016) and 0.57

(Torkamani et al., 2014) with a mean of 0.49. Self-

efficacy is also frequently measured and in two

studies the Cohen’s d found are between 0.28

(Beauchamp et al., 2005) and 0.77 (Lorig et al., 2010)

with a mean of 0.52. Cohen’s d for stress in present

in three studies and is between 0.13 (Beauchamp et

al., 2005) and 0.5 (Lorig et al., 2010), with a mean of

0.24. For anxiety, Cohen’s d is between 0.15

(Beauchamp et al., 2005) and 0.51 (Griffiths et al.,

2016) with a mean of 0.38 in three studies. Cohen’s d

for depression is measured by two studies and the

result found was 0.26 (Blom et al., 2015) and 0.52

(Griffiths et al., 2016), with a mean of 0.39. The

Cohen’s d was also available for four studies on

disruptive behavior studies. The Cohen’s d was

between 0.11 (Kajiyama et al., 2013) and 0.71 (Kwok

et al., 2014), with a mean of 0.49. Single studies also

provides Cohen’s d for many variables. Internet

intervention seems to have a small effect on fatigue

(0.08; Beauchamp et al., 2005), depressive symptoms

(0.10; Beauchamp et al., 2005), trust in decision

(0.31; Brennan et al., 1995), asking for help (0.25:

(Beauchamp et al., 2005), positive aspects of

caregiving (0.25; Beauchamp et al., 2005), reaction

(0.43; Griffiths et al., 2016) and distress (0.47; Kwok

et al., 2014) associated with disruptive behaviors.

Moderate Cohen’s d was found in the perception of

caregiving demands (0.49), obtaining respite (0.59)

and cognition with caregiving role (0.52; Glueckauf

et al., 2004).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Conclusions of This Review

In conclusion, this review presented an overlook of

22 studies measuring the effectivity of internet

interventions for caregivers. It showed that internet

interventions include a large diversity of intentions,

from synchronous psychoeducation to web therapy.

The variables used to measure the effectiveness of

these programs also differ from one to another. Some

studies focused on caregiver variable (ex. feeling of

burden, stress, depression, anxiety, etc.), on their

relation to the care receiver (ex. reaction to disruptive

behaviors, self-efficacy, positive aspects of

caregiving, better understanding of the illness, etc.)

and even of the care receiver himself (disruptive

behaviors occurrence and severity).

Theses internet intervention programs showed

their versatility with their improvement of the

caregiver’s psychological well-being (Blom et al.,

2015; Glueckauf et al., 2004; Griffiths et al., 2016;

Lorig and al., 2010), with promoting tools to improve

the caregiving relationship (Beauchamp et al., 2005;

Boots et al., 2016; Glueckauf et al., 2004; Griffiths et

al., 2016; Lorig et al., 2010) and even with improving

the care receiver’s behavior (Griffiths et al., 2016;

Kajiyama et al., 2013; Kwok et al., 2014). However,

we found a great variability in the effectivity

measured. In fact, 57% of the studies showed a

significant impact of the program on the caregivers.

Even if a majority of studies showed significant

impact on stress, anxiety and self-efficacy, more

studies are needed to measure the impact of these

programs on the burden, depressive symptoms and

reaction to disruptive behaviors. As internet

intervention programs will probably increase in the

next years, further studies will need to document the

effect of these kinds of interventions with a larger

number of studies to compare and less variability in

the programs assessed and variables measured.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

100

4.2 Reflexion on Internet Intervention

In a larger view, literature shows issues with the

description and classification of interventions. In fact,

the authors differ in their way of describing their

interventions, so what ones consider psychoeducation

can be considered therapy by one another. This

therefore brings an important limitation in the

comparison of studies.

A standardization proposing clear descriptions for

each type of intervention would be preferred in order

to unify the literature. It would also be appropriate to

encourage authors to provide a more detailed

description of the intervention delivered. This

description is unfortunately missing in most of the

articles (Gaugler, Jutkowitz, Shippee and Brasure,

2017). Moreover, the complexity of the interventions

offered complicates the interpretation of the results.

In fact, the majority of studies combine several

modalities of intervention (e.g. a website and a

forum). It is therefore difficult to identify which

modality has beneficial results for caregivers. New

studies aiming at isolating the active agent from the

treatments offered would therefore be necessary in

order to clarify the conclusions on the interventions

by the Internet.

Finally, the increasing popularity of Internet

interventions brings some challenges with updating

the knowledge of caregivers. In this sense, studies are

rapidly outdated due to technological advances.

Therefore, new updates will always be required.

REFERENCES

Åkerborg, Ö., Lang, A., Wimo, A., Sköldunger, A.,

Fratiglioni, L., Gaudig, M., and Rosenlund, M., 2016.

Cost of Dementia and Its Correlation with Dependence.

Journal of Aging and Health, 1–17.

Bass, D. M., McClendon, M. J., Brennan, P. F., and

McCarthy, C., 1998. The buffering effect of a computer

support network on caregiver strain. J Aging Health,

10(1), 20-43. doi:10.1177/089826439801000102.

Beauchamp, N., Irvine, A. B., Seeley, J., and Johnson, B.,

2005. Worksite-Based Internet Multimedia Program for

Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia.

Gerontologist, 45(6), 793-801. doi:10.1093/geront/45.

6.793.

Blom, M. M., Bosmans, J. E., Cuijpers, P., Zarit, S. H., and

Pot, A. M., 2013. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

of an internet intervention for family caregivers of

people with dementia: design of a randomized

controlled trial. BMC psychiatry, 13(1), 17.

Blom, M. M., Zarit, S. H., Groot Zwaaftink, R. B., Cuijpers,

P., and Pot, A. M., 2015. Effectiveness of an Internet

intervention for family caregivers of people with

dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial.

PLoS One, 10(2), e0116622. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.

0116622.

Boots, L. M. M., Vugt, M. E., Knippenberg, R. J. M.,

Kempen, G. I. J. M., & Verhey, F. R. J., 2014. A

systematic review of Internet‐ based supportive

interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia.

International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 29(4),

331-344.

Boots, L. M., de Vugt, M. E., Withagen, H. E., Kempen, G.

I., and Verhey, F. R., 2016. Development and initial

evaluation of the web-based self-management program

“partner in balance” for family caregivers of people

with early stage dementia: an exploratory mixed-

methods study. JMIR Res Protoc, 5(1).

Brennan, P. F., Moore, S. M., and Smyth, K. A., 1995. The

effects of a special computer network on caregivers of

persons with Alzheimer's disease. Nursing research,

44(3), 166-172.

Brodaty, H., Woodward, M., Boundy, K., Ames, D.,

Balshaw, R., and PRIME Study Group., 2014.

Prevalence and predictors of burden in caregivers of

people with dementia. The American Journal of

Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(8), 756-765.

Camateros, C., and Vézina, J., 2016. Évaluation d’une

intervention par conférence web à l’intention d’aidantes

d’un proche atteint d’un trouble neurocognitif sévère.

NPG Neurologie-Psychiatrie-Gériatrie, 16(96), 320-

325.

Chiu, T., Marziali, E., Colantonio, A., Carswell, A.,

Gruneir, M., Tang, M., and Eysenbach, G., 2009.

Internet-based caregiver support for Chinese Canadians

taking care of a family member with Alzheimer's

disease and related dementia. Can J Aging, 28(4), 323-

336. doi:10.1017/S0714980809990158.

Collins, L. G., & Swartz, K., 2011. Caregiver care.

American family physician, 83(11), 1309.

Cristancho-Lacroix, V., Wrobel, J., Cantegreil-Kallen, I.,

Dub, T., Rouquette, A., and Rigaud, A. S., 2015. A

web-based psychoeducational program for informal

caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease: a pilot

randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res, 17(5),

e117. doi:10.2196/jmir.3717.

Finkel, S., Czaja, S. J., Schulz, R., Martinovich, Z., Harris,

C., and Pezzuto, D., 2007. E-care: a telecommunica-

tions technology intervention for family caregivers of

dementia patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 15(5), 443-

448. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180437d87.

Gaugler, J. E., Kane, R. L., Kane, R. A., and Newcomer, R.,

2005. The longitudinal effects of early behaviour

problems in the dementia caregiving career. Psychol

Aging, 20(1), 100-116. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.

100.

Glueckauf, R. L., Ketterson, T. U., Loomis, J. S., and

Dages, P., 2004. Online support and education for

dementia caregivers: overview, utilization, and initial

program evaluation. Telemed J E Health, 10(2), 223-

232. doi:10.1089/tmj.2004.10.223.

Griffiths, P. C., Whitney, M. K., Kovaleva, M., and

Hepburn, K., 2016. Development and Implementation

Internet Interventions for Family Caregivers of People with Neurocognitive Disorder

101

of Tele-Savvy for Dementia Caregivers: A Department

of Veterans Affairs Clinical Demonstration Project.

Gerontologist, 56(1), 145-154. doi:10.1093/geront/

gnv123.

Hicken, B. L., Daniel, C., Luptak, M., Grant, M., Kilian, S.,

and Rupper, R. W., 2016. Supporting Caregivers of

Rural Veterans Electronically (SCORE). The Journal of

Rural Health.

Jajor, J., Rosołek, M., Skorupska, E., Krawczyk-

Wasielewska, A., Lisiński, P., Mojs, E., and Samborski,

W., 2016. ''UnderstAID–a platform that helps informal

caregivers to understand and aid their demented

relatives”–assessment of informal caregivers–a pilot

study. Journal of Medical Science, 84(4), 229-234.

Kajiyama, B., Thompson, L. W., Eto-Iwase, T., Yamashita,

M., Di Mario, J., Marian Tzuang, Y., and Gallagher-

Thompson, D., 2013. Exploring the effectiveness of an

internet-based program for reducing caregiver distress

using the iCare Stress Management e-Training

Program. Aging Ment Health, 17(5), 544-554.

doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.775641.

Kamiya, M., Sakurai, T., Ogama, N., Maki, Y., and Toba,

K., 2014. Factors associated with increased caregiver’s

burden in several cognitive stages of Alzheimer ’ s

disease. Geriatric Gerontology, 14(Suppl. 2), 45–55.

http://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12260.

Keefe, J., and Manning, M. (2005). The Cost Effectiveness

of Respite: A Literature Review.

Kelly, K., 2003. Link2Care: Internet-based information and

support for caregivers. Generations, 27(4), 87-88.

Kwok, T., Au, A., Wong, B., Ip, I., Mak, V., and Ho, F.,

2014. Effectiveness of online cognitive behavioural

therapy on family caregivers of people with dementia.

Clin Interv Aging, 9, 631-636. doi:10.2147/CIA.

S56337.

Lai, C. K., Wong, L., Liu, K. H., Lui, W., Chan, M., and

Yap, L. S., 2013. Online and onsite training for family

caregivers of people with dementia: results from a pilot

study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 28(1), 107-108.

Lorig, K., Thompson-Gallagher, D., Traylor, L., Ritter, P.

L., Laurent, D. D., Plant, K., . . . Hahn, T. J., 2010.

Building Better Caregivers: A Pilot Online Support

Workshop for Family Caregivers of Cognitively

Impaired Adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology,

31(3), 423-437. doi:10.1177/0733464810389806.

Marziali, E., Damianakis, T., and Donahue, P., 2006.

Internet-Based Clinical Services: Virtual Support

Groups for Family Caregivers. Journal of Technology

in Human Services, 24(2-3), 39-54. doi:10.1300/

J017v24n02_03.

Marziali, E., and Garcia, L. J., 2011. Dementia caregivers'

responses to 2 Internet-based intervention programs.

Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 26(1), 36-43.

doi:10.1177/1533317510387586.

O'Connell, M. E., Crossley, M., Cammer, A., Morgan, D.,

Allingham, W., Cheavins, B., Morgan, E., 2014.

Development and evaluation of a telehealth

videoconferenced support group for rural spouses of

individuals diagnosed with atypical early-onset

dementias. Dementia (London), 13(3), 382-395.

doi:10.1177/1471301212474143.

O'Connor, M. F., Arizmendi, B. J., and Kaszniak, A. W.,

2014. Virtually supportive: a feasibility pilot study of

an online support group for dementia caregivers in a 3D

virtual environment. J Aging Stud, 30, 87-93.

doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.03.001.

Torkamani, M., McDonald, L., Aguayo, I. S., Kanios, C.,

Katsanou, M.-N., Madeley, L., Jahanshahi, M., 2014. A

randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate a

technology platform for the assisted living of people

with dementia and their carers. Journal of Alzheimer's

Disease, 41(2), 515-523.

van der Roest, Meiland, F. J., Jonker, C., and Droes, R. M.,

2010. User evaluation of the DEMentia-specific Digital

Interactive Social Chart (DEM-DISC). A pilot study

among informal carers on its impact, user friendliness

and, usefulness. Aging Ment Health, 14(4), 461-470.

doi:10.1080/13607860903311741.

Wiprzycka, U. J., Mackenzie, C. S., Khatri, N., and Cheng,

J. W., 2011. Feasibility of recruiting spouses with

DSM-IV diagnoses for caregiver interventions.

Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological

Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(3), 302-306.

ICT4AWE 2018 - 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

102