Hidden within a Group of People

Mental Models of Privacy Protection

Eva-Maria Schomakers, Chantal Lidynia and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52072 Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Privacy, Privacy Protection, Mental Models, User Interface Design, Privacy Literacy, k-anonymity.

Abstract: Mental models are simplified representations of the reality that help users to interact with complex systems.

In our digitized world in which data is collected everywhere, most users feel overtaxed by the demands for

privacy protection. Designing systems along the language of the users and their mental models, is a key

heuristic for understandable design. In an explorative approach, focus groups and interviews with 18

participants were conducted to elicit mental models of internet users for privacy protection. Privacy protection

is perceived as complex and exhausting. The protection of one’s identity and, correspondingly, anonymity are

central aspects. One research question is how scalable privacy protection can be visualized. Physical concepts,

like walls and locks, are not applicable to the idea of adjustable privacy protection. The concept of k-

anonymity – visualized by a group of people from which the user is not distinguishable – can be related to by

most of the participants and seems to work well as symbolization, but it is not yet internalized as mental

model. Initially, users see privacy protection as binary – either one is protected or not. Thus, the concept of

adjustable privacy protection is new to lay-people and no mental models exist, yet.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today, online services and internet usage, be it via

desktop computer, laptop, or mobile devices such as

tablet PCs or smartphones, are integral parts of every-

day life. The World Wide Web is used to search for

information, to stay in touch with friends and family,

to work, to play, and pass the time, to name but a few

options. And especially smartphones are ubiquitous.

With all of these online services available, every

user creates data that they leave or actively publish

on the Internet. Search histories, posts on social

networks, visits on e-commerce sites, they all

generate digital data, so-called digital footprints. And

today’s users are well aware and oftentimes opposed

to and concerned about the collection of that data and

the associated risks. Therefore, users try to protect

their privacy as best as possible: they use fake

accounts, pseudonyms, and try to not have photos

with their faces online (cf., Vervier et al. 2017; Ziefle

et al. 2016).

Different spheres require different definitions of

privacy. Burgoon (1982) distinguishes between

physical, social, psychological, and informational

privacy. Physical privacy can be protected by means

of closed doors, curtains, and garden fences, all of

which are easy to relate to as the results (not being

visible or viewed anymore) can be directly controlled.

When dealing with the online environment, it is

especially users’ information privacy at stake, and the

protection of that is growing increasingly complex as

more and more technical threats exist.

Users try to protect their online privacy but often

they do not know how to do so effectively. Privacy

protection is perceived as too complex to be able to

do so, and also as not operative anymore (Zeissig et

al. 2017). Therefore, most online users are concerned

about their privacy (European Commission 2015).

Within the research project myneData (funded by

the German Ministry of Education and Research),

academics from different disciplines (communication

science, law, computer science, etc.) are looking for a

way of providing adequate protection of one’s own

data while at the same time offering the benefits of

data analysis to trustworthy data processors by

developing a user-controlled ecosystem for sharing

personal data. The main idea is a platform in which

users can provide data they are willing to share and

offer this to data processors, for example, researchers,

for free or in return for a compensation. Depending

on each user’s privacy settings, previously specified

data is aggregated from many different users and the

resulting data set is anonymized and made available

to the data processors. For a more detailed depiction

Schomakers, E., Lidynia, C. and Ziefle, M.

Hidden within a Group of People.

DOI: 10.5220/0006678700850094

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS 2018), pages 85-94

ISBN: 978-989-758-296-7

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

85

of that project, see Matzutt et al. (2017). One vital

aspect, especially in myneData, is the comprehensible

visualization of privacy protection and security, so

that every user can understand and interact with the

system. To do so, it is invaluable to know the ideas

and pre-existing notions users have of privacy

protection and to integrate these notions and users’

knowledge into the system and interface design. A

possible and promising approach is the use of mental

models (Coopamootoo & Groß 2014a; Coopamootoo

& Groß 2014c).

In line with Gentner & Stevens (2014), mental

models refer to the cognitive representations of how

technical systems or interfaces might work, thereby

including persons’ beliefs, cognitive and affective

expectations about the functions and the consequences

regarding implementation procedures or personal use

(Zaunbrecher et al., 2016).

Especially in the context of risk and risk

perception, the study of users’ mental representations

has been used extensively in order to best

communicate potential risks (Raja et al. 2011).

Although mental models are not necessarily true

representations of the real world, they facilitate the

understanding of complex or abstract issues (e.g.,

Morgan et al. 2002; Asgharpour et al. 2007). Thus,

they help users to interact with complex systems.

Mental models concerning risks and risk

perception in the online environment have been

studied and described by Camp (2009). She has found

five predominant mental models, namely physical

security, medical security, criminal behavior,

warfare, and economic failure that depict the most

common associations of how online risks are

perceived or visualized by people.

Physical security means the risk is linked to a

break-in in your home. Therefore, obvious depictions

are open and closed (pad)locks. Medical security

means infecting the computer or smartphone with a

virus. Criminal behavior is what, for example, hackers

are thought to do. Here the associated threats are data

theft but also vandalism in the vein of destroying the

functionality of the computer. Warfare as mental

model for online security risks is based on fast response

times that are needed and the huge potential losses of

resources that follow an attack. Economic failure

encompasses financial losses by illicit access to one’s

online bank-accounts or payment options.

And while not exhaustive and always applicable,

these associations with the real world to make

sense of the virtual world are the quintessential

idea of mental models (e.g., Asgharpour et al. 2007;

Coopamootoo & Groß 2014a; Coopamootoo & Groß

2014b).

Asgharpour et al. (2007) have also found that

especially physical security – meaning the idea of

people physically entering your private space or

breaking your locks – is the best way to describe the

risks prevalent in the online environment. Seeing an

open or closed lock is an image that most people can

easily reconcile with protecting their goods, material

or virtual. In the same vein, Dourish et al. (2003) have

found that security is often seen as a barrier, locking

someone out and preventing access to private

information.

Motti and Caine (2016) offer a “visual vocabulary

for privacy concepts” but deal mostly with four main

aspects of privacy: data collection, data transmission,

data storage, and data sharing and access control.

Although helpful, this does not necessarily suggest a

mental model for the protection of one’s privacy.

However, imagery such as shields, keys, and locks are

oftentimes associated with privacy control and

therefore security (Motti & Caine 2016).

Still, a visual vocabulary is not necessarily the

only way to find out what people think the protection

of their information privacy may look like. For

example, Prettyman et al. (2015) have found that

many users hold the belief that they have nothing of

value, so protection is not as important and therefore

neglected. Another common association is that

keeping up protection is a lot of hard work and takes

time and effort, so oftentimes it is outsourced to

people perceived as experts – either a professional or

computer-savvy friend or relative. Also, studies have

found a fatalistic attitude as putting all that effort into

privacy protection is useless because who gets access

to the data is not in the users’ hands anyway (e.g.,

Zeissig et al. 2017; Prettyman et al. 2015).

2 RESEARCH DESIGN

The aim of this study is to (a) identify mental models

of privacy protection and to (b) discuss options to

visualize comprehensible control elements for adjust-

able privacy protection that match these mental models.

To do so, an explorative approach is needed as

there is no previous knowledge about the nature of the

mental models in this context. Next, a short overview

about methods to identify mental models and their

(dis)advantages is given, before we describe the

empirical procedure, analysis, and the sample.

2.1 Eliciting Mental Models

Mental models can be compared to the lenses through

which individuals see the object, concept, or topic in

IoTBDS 2018 - 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

86

questions (Coopamootoo & Groß 2014c). They are

internalized and may not be conscious, as one is not

aware of the type of glass one looks through. Several

methods for identifying or eliciting mental models

have been proposed in research. They are

distinguished as either direct or indirect.

Direct elicitation approaches, in which the

participants are asked directly to explain or draw the

concept in question and all their associations with it,

rely on the ability of the subjects to report and

articulate their understanding of the concept (Olson &

Biolsi 1991; Ziefle & Bay 2004; Zaunbrecher et al.

2016). In contrast, indirect elicitation extracts mental

models from written documents or verbal texts about

the topic in questions and, thus, rely mostly on the

interpretation of the interviewer (Jones et al. 2011).

Grenier and Dudzinska-Presmitzki (2015) point

out that, as cognition is not only based on language

but also on images, verbal as well as graphical

techniques can be used to elicit mental models. They

caution that strictly verbal accounts run the risk of

being incomplete, given that participants are not

always conscious of their thought structures.

Therefore, a mix of verbal and graphical techniques,

in which the participants are asked to draw their

representation of the concept, gives the opportunity to

generate a more holistic presentation (Grenier &

Dudzinska-Przesmitzki 2015).

Focus groups have the advantage that the

discussion between the participants is encouraged and

different opinions and ideas stimulate a broad

examination of the topic, as, for example, Courage

and Baxter (2005) described. But there are also

possible drawbacks as some participants may hold

back their ideas or are very much influenced by the

other opinions. In this regard, interviews promote

more detailed insights into participants’ opinions and

ideas. The participants are not interrupted and judged

by other participants and are thus encouraged to

express themselves freely and elaborate on the topic

(Courage & Baxter 2005).

In this explorative approach, identifying all

existing mental models and associations was

paramount. Thus, a mixture between the techniques is

chosen that combines their respective advantages.

Three focus groups are supplemented with five

interviews, all of which followed the same procedural

guide. Both verbal and graphical tasks were mixed.

The participants were not only encouraged to define

privacy protection directly but also to talk about the

topic in general, which was used in the analysis to

identify and confirm mental models and associations

indirectly from their reasoning.

2.2 The Sample

The sample was composed of 11 men and 7 women

between the age of 17 and 57 years (M=32.6, SD=

13.5). Three focus groups with overall 13 participants

were conducted, which were replenished by five

individual interviews. The participants were recruited

through personal contacts in the wider social network

of the interviewer with the goal to include people of

differing level of privacy knowledge and digital

skills. A privacy literacy test was applied after the

interviews (adopted from Trepte et al., 2015) in which

the participants reached between 7 and 16 points of

18 maximum points (M=11.4, SD=2.6). More than

half of the sample were students, some majoring in

computer science. Those majoring in computer

science, who also all reached a very high score in the

privacy literacy test, are considered as expert

participants especially for their knowledge about

anonymization algorithms.

2.3 The Procedure

After introducing the general topic of digitization and

online privacy, the group discussions were initiated

with the question “What do you do online?” as intro-

ductory part. The goal of this question was for the

participants to delve into the topic with all its facets.

Then, the questions were raised what privacy

protection is to the participants and how they try to

protect their data. Every participant completed the

sentence “Privacy protection to me is (like)…” at the

beginning of the discussion.

After this abstract part, a specific scenario was

introduced that provided a similar decision situation

as in the myneData ecosystem, without explaining

this complex concept. In this scenario, data was

requested by a research institute for a medical study

and the participants were able to choose what data

they are willing to provide and to adjust the level of

privacy protection that is given to this information.

Again, the question was asked “What does data

protection mean to you in this scenario?” The

participants should discuss how levels of protection

differ and what the upper and lower limits are.

Then they were asked to draw control elements

for privacy protection. After the discussion of their

own drawings, pictures of different control elements

and possible metaphors for privacy protection were

presented as stimulator for the discussion. The

pictures featured scales from other contexts, e.g., a

speedometer, thermometer, as well as simple slide

switches, rating mechanisms like thumbs-up and

downs and smileys, and, furthermore, symbols for

Hidden within a Group of People

87

protection in other contexts, e.g., a wall, a garden

fence, and a padlock, that match the mental models

that Dourish et al. 2003 and Asgharpour et al. 2007

found. The participants were asked to discuss the

advantages and disadvantages of those visualizations.

At the end, every participant was asked to summarize

what they deem important concerning privacy

protection.

After the focus groups and interviews, a short

questionnaire was handed out to collect demographic

data (age, gender, occupation, etc.). Additionally, the

questionnaire contained a short privacy literacy test

that was adapted and abbreviated from Trepte et al.

(2015). The test included very simple to very

advanced multiple-choice questions about digital

knowledge (“What is a cookie?”), privacy rights

(“What rights do you have online?”), technical

privacy protection methods (“How can users protect

their online privacy?”), and data collection methods

(“What technical options exist for data collection?”).

2.4 Data Analysis

The interviews and focus groups were audiotaped and

transcribed verbatim. A conventional content analysis

(cf. Hsieh & Shannan 2005) was conducted to derive

categories from the data. Two coders worked through

the material several times and settled all differences

in coding through discussions.

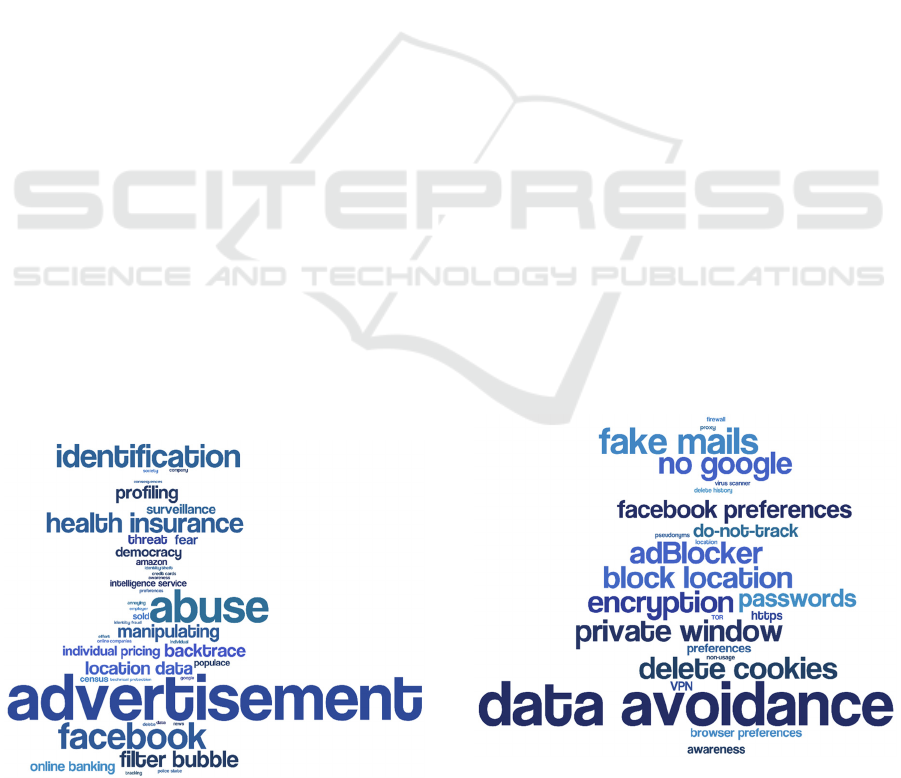

Word clouds were generated at the website

wordle.net (Feinberg 2014). To do so, each quote in

an individual category was assigned one or several

keywords, thus all interviews and focus groups are

included. The font size is proportionate to the number

of mentions, in order to allow for a direct evaluation

of the most frequent (and important) mentions. The

study took part in Germany with German native

speakers. For this publication, quotations and

keywords were translated to English.

Figure 1: Topics and associations participants link to

privacy protection.

3 RESULTS

Our analysis showed that privacy protection is

perceived as multi-layered and complex, and that the

participants differ in their understanding of the topic.

There are various parties of responsibility for privacy

protection, different perceived threats, and, thus,

different options for protection. Figure 1 shows this

factor space of topics and associations related to the

concept.

The adjustable privacy protection addressed in the

scenario in the second part of the interviews and focus

groups is a special case in which the participants

applied a different focus.

Thus, in the following section, first the results

regarding privacy protection as broad concept are

presented. Afterwards, we focus on privacy

protection as the participants define it in the scenario

of providing a data set. In this course, we will also

discuss visualization options of privacy protection.

3.1 Who Is Responsible for Privacy

Protection?

“On the one hand, there is one aspect of self-

determination, where you can decide when using a

service what you want to divulge. […] And data

security is the aspect of technical protection, as in how

do companies and other parties that store my data,

ensure that it is safe. And there is a third aspect of how

it is regulated by the law” (P17).

This quote from one of our participants shows the

threefold division that permeates the discussions.

There is a personal responsibility to avoid generating

data in the first place and to protect privacy by

technical means. One participant even sees this as the

only responsibility:

“The protection of my data lies in my own

responsibility. I have to take care of it myself. If I don’t

I mustn’t complain” (P15).

Other participants emphasize that control and self-

determination are preconditions for this personal

privacy protection and that, at the very least,

transparency is needed:

“Data protection is at least the attempt to make the

data flow transparent and, also, an obligation that the

individual can keep track and keep control about her

own data” (P9).

As for the second level, only a few participants

reported to be aware that data which is stored by

companies and other data collectors is protected from

IoTBDS 2018 - 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

88

third parties. The third aspect of legal regulations are,

on the other hand, mentioned quite often:

“[…] privacy protection is the right to decide where

my data goes” (P2).

“[…] privacy protection is like a statute book or a

duties record book, in which it is regulated what

practices are allowed – or just what is not allowed.

And there are some things that are only allowed under

specific restrictions […]” (P6).

3.1.1 From What Do You Want to Be

Protected?

When asked to define privacy protection, many

participants started by listing from what they want to

be protected. Some participants even define privacy

protection as the absence of negative consequences:

“Privacy protection is for me, for example, if I

wouldn’t get any more unwanted promotional emails”

(P12).

The word cloud in Figure 2 shows the perceived

threats. These threats include most of the risk

associations found by Camp (2009). One focus lies on

the criminal behavior and illicit abuse of data. Also

financial risks are addressed. But the participants in

this study address additional threats to privacy.

One threat is already seen in the data collection

itself, e.g., the collection of location data and data

from social networks. Additionally, they want to be

protected against personal consequences, but not only

illicit ones. Targeted advertisement and individual

pricing have been named often throughout the

discussions. Moreover, some participants see a threat

for society and democracy, e.g., because of

manipulation possibilities and filter bubbles.

Figure 2: Word cloud of perceived threats to online privacy.

Font sizes reflect the frequency of mentions.

One conceptual threat is addressed very often

throughout the discussion and interviews: identifica-

tion. Participants oppose the notion that others can

“form a picture of themselves” (P2) (a German idiom

meaning to form an opinion about themselves), that

“apps can identify yourself,” that “data is traced

back to yourself,” and that “data is combined to

individual profiles” (P6). Apart from the abstract

threats for democracy and society that are only

mentioned by few participants, it is their identity and

the “me” that participants want to protect. Their

verbalizations suggest that they see identification as

the key problem and not being identified as the one

mechanism that can protect them from all threats,

e.g., “privacy protection is the security of my

identity” (P16) or “privacy protection is the

protection of being identified” (P10).

The different types of threats can also be

recognized in how the participants currently manage

their privacy protection (cf. Figure 3). Some of the

options for online privacy protection aim at

disguising the identity while using the internet (TOR,

VPN) or try to revoke tracking itself (do-not-track

and deletion of cookies). Others block the

consequences of data collection (Ad blocker, fake

email addresses). Firewalls, virus-scanners as well as

passwords aim at protecting data from access by third

parties that try to use data illegally.

But most participants also use a rather

straightforward approach by trying to avoid the

generation of data in the first place (data avoidance).

Services that are well-known for collecting a lot of

data are not used, the GPS signal of the smart phone

is switched off, and only information that is essential

is provided in online forms (e.g., the address for

online purchases).

Figure 3: Word cloud of measures of privacy protection.

Font sizes reflect the frequency of mentions.

Hidden within a Group of People

89

One participant states that “privacy protection

means that no other person but myself has access to

my data” (P8).

This raises the question against whom privacy

protection is needed. The participants name online

companies, (health) insurance companies, hackers,

intelligence services, and other users. Some

differentiate between the intended communication

partner and “unauthorized listeners.”

3.1.2 Complex, Exhausting, and Almost

Impossible

When asked about privacy protection, several

participants emphasized the complexity and lack of

clarity of technical privacy protection procedures.

Another characteristic is the effort that privacy

protection takes, as was also described by Prettyman

et al. (2015). For example, one participant says:

„Privacy protection is like a heavy tome about

advanced mathematics. I would need to work through

it before I could understand it” (P16).

Moreover, it is described as “a Sisyphean task, it

is never finished” (P13), which again underlines the

complexity of the topic to the user. One participant

with a lower score in the privacy literacy test even

describes privacy protection as impossible:

“Privacy protection is for me as impossible as hiding

a diary from curious eyes. In the moment that the diary

is written, the threat exists that it is read. The only

protection would be not to write a diary” (P12).

All participants see importance in privacy

protection.

“Privacy protection to me is like digestion:

exhausting, unappetizing, and one does not reflect

enough about it, although it is a very important topic”

(P11).

3.2 Privacy Protection in the Scenario

With the introduction of the scenario, the focus

shifted towards privacy protection when providing a

specific data set. Some of the variables in the factor

space of privacy protection as discussed before are

now predetermined.

In the scenario, privacy protection is narrowed

down to a case in which data is requested by a

research institute for the purpose of a medical study.

1

If the information for each person within a dataset cannot be

distinguished from at least k-1 other persons whose information

Either Protected or Not: Initially, some participants

describe privacy protection as an absolute, binary

characteristic: “Privacy protection is something

absolute, data is either protected or not” (P18). But

after delving deeper into the topic, these opinions

changed

Anonymity: Most participants put their focus on

anonymity (or rather, not being identified as

individual) as the key aspect of privacy protection

within this scenario: “The most important thing for

me would be anonymity” (P11).

But the understanding of anonymity differs very

much, also depending on the technical knowledge.

Some participants state that anonymity means “one

cannot match a person to the data anymore” (P8) and

participants with technical background refer to the

concept of k-anonymity

1

.

Others only want information to be deleted that

identifies them directly: “that my name is replaced

with participant number X” (P18). The same

participant comments that “anonymity is sometimes

only that someone just doesn’t use the data in any way

although it would be possible.” Thus, she does not

even request technical protection.

Transparency, Benefits, Trust: The participants

address multiple factors that influence their

willingness to provide data in this scenario. These

factors also show inversely what is important

regarding privacy protection. Of great importance is

the type of data that is requested, the data collector,

and the purpose of the collection. A key criterion is

that they can understand why this type of data is

relevant for the analysis. How the data is collected

and stored, the benefit for the individual and the

society, and transparency about the data use are

additional influences. Another very important aspect

is the trust into the data collector and their good will

not to identify the person or do any harm even if

technically possible.

3.3 How to Visualize Adjustable

Privacy Protection

The participants were asked to draw adjustable

privacy protection freehand. Additionally, control

elements and visualization from other contexts were

presented as stimulus for further discussion.

Half of the participants felt privacy protection to

be so abstract and far-fetched, they felt incapable of

drawing a picture. Most of the pictures included

is in this data set, the data set provides k-anonymity protection

(Sweeney 2002).

IoTBDS 2018 - 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

90

mainly text and no symbols. It seems that no visual

representation for privacy protection is obvious or

retrievable.

The remaining drawings and the discussion of the

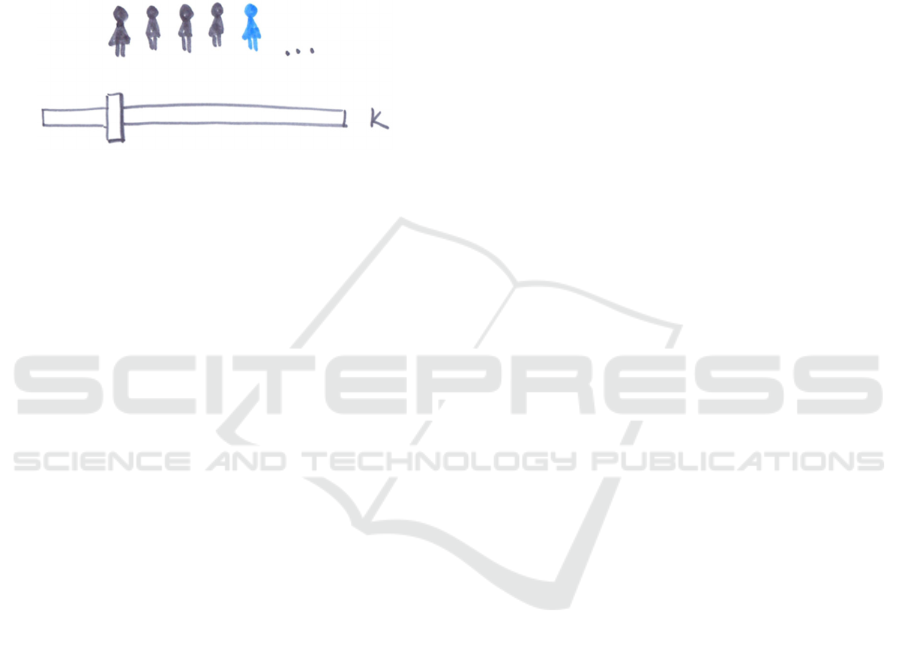

stimulus material revolved around the idea of k-

anonymity that some participants introduced to the

others. For example, one participant drew a picture of

a slide control and “the group in which I am hidden,

that becomes smaller or larger with the slider” (P18)

(see Figure 4).

Figure 4: A participant’s attempt at visualizing controllable

privacy protection.

This idea is also mentioned in other interviews

and focus groups. But it seems that this focus is

artificially developed by the framing through the

discussion about k-anonymity. This was the only

concept that was explained for anonymity and was,

thus, adopted by the other participants. It can also be

surmised that not all participants fully understood the

concept. For example, one participants stated:

“You could for example depict the sample as small

people and then you can explain that this is the group

within which you are not identifiable” (P2).

Equating “the sample” with “the group within which

you are not identifiable” suggests a misunderstanding

of the concept.

The idea of privacy protection as a physical

barrier was introduced to the participants with the

stimulus material in which both a brick wall and a

wooden fence were included. Those ideas were

picked up by two participants:

“Privacy protection is like a garden fence, it protects

my privacy” (P10) and

“Privacy protection is like a semi-permeable wall,

that when it gets denser, doesn’t allow any more data

to go through. And when you scale it to be less dense,

up to absolute permeability, it allows all data to flow

through” (P6).

Also, the idea of a padlock was introduced and

some participants liked this from the get-go:

“I like the visualization of the padlock, because you

can see that if it is open, you want to provide the data,

instead of checkboxes. If it is closed it means that you

do not want to provide the data” (P2).

Note that those metaphors were mentioned after

the stimuli were introduced. Thus, they did not come

spontaneously from the participants and were taken

up, as was the idea of k-anonymity. But most

participants criticized these symbols as too simple.

This is a criterion that was often mentioned in the

evaluation of the stimulus material: most

visualizations were perceived as not able to cover the

complexity of the topic.

“For me, it is important to read a text, what is done in

detail, because visualizations do not reach the

necessary level of detail” (P7).

Some participants stated that they would not feel

taken seriously when such “childish” visualizations

would be used in this serious context. Based on this,

they would lose their trust in such a user interface.

In this scenario, in which the participants are

offered actual control over their data – something

they currently do not have in most online situations –

this power is received with open arms.

Correspondingly, being able to set privacy

protection in just two or three levels is no longer

enough, e.g.: “I want to see that there are several

increments and that I can set them as I wish” (P18).

The symbols proposed by other authors, e.g., barriers

or locks, do not offer scaling options and, thus, were

rejected by the participants.

The mental model of medical security, which was

also identified by Camp 2009 as an associated risk,

was similarly addressed by one participant at the end

of the discussion. She compared privacy protection to

a vaccination but emphasized mostly the idea of

personal responsibility:

“

I would compare it to a vaccination. It is something

you have to take care of and that protects you, but only

if you have taken care of it” (P18).

4 CONCLUSION

Mental models are simplified representations derived

from the physical world that people use to understand

and interact with complex or abstract topics and

issues. They have been found very helpful to

understand and communicate risk perception

(Coopamootoo & Groß 2014a). Also privacy research

has seen merit in using this approach to understand

computer users and their online behavior better (e.g.,

Asgharpour et al. 2007; Camp et al. 2007;

Coopamootoo & Groß 2014b; Wash 2010). In the

Hidden within a Group of People

91

present study, five interviews and three focus groups

with overall 18 participants were carried out to

identify mental models and possible visualizations of

privacy protection. Participants with differing

technical knowledge about online privacy were

included in the study, as it was hypothesized that their

mental models differ in level of detail and accuracy,

based on, e.g., (Coopamootoo & Groß 2014a).

The analysis showed that privacy protection is

perceived as a complex concept with many

influencing factors. No simplistic, easy to use mental

model was identified in our sample, but clues for

some useful models were extracted. It was hard for

the participants to directly define privacy protection

but many related topics were discussed: Who is

responsible for privacy protection? Against what and

whom is protection needed or wanted? How is

privacy protection currently managed? What are

preconditions for successful privacy protection?

Those different topics show that privacy protection is

context-dependent: It can be the protection of the

individual against targeted advertising by online

companies, or, it is the protection of stored data by

online companies against hackers. And it should also

always be somehow supported by law and

regulations.

Complex is the attribute that all participants

agreed upon for privacy protection. Also, the results

of Prettyman et al. 2015, namely that one important

perception is that privacy protection takes much

effort, are mirrored in this study. However, her

findings that privacy protection is perceived as

irrelevant because users have nothing to hide was not

replicated, at least not in this German sample. In our

sample, the participants emphasized the importance

of privacy protection. As this is a qualitative study

with a very small sample size, we cannot generalize

these findings. Still, they could be, in fact, culturally

sensitive. Studies dealing with international

differences regarding information privacy show that

there are large differences across nations in this

regard (cf. Culnan & Armstrong 1999; Trepte &

Masur 2016).

The risk associations found by Camp (2009) were

mostly also present in our study. Many participants

described privacy protection as the absence of

negative consequences and listed those threats.

Especially criminal behavior and financial losses

were addressed often. But we found another focus: At

its core, our analysis showed privacy to be understood

as the protection of the individual and his or her

identity. Additionally, data collection itself, the

“annoying” targeted advertising and “unfair”

individual pricing, and also the protection from

manipulation of society and democracy were

addressed.

Initially, privacy protection is felt to exist only on

a binary level – either one’s privacy is protected or it

is not. This approach is revised by the participants

once they delved deeper into the topic, its complexity,

and the idea of adjustable privacy.

The central point of identity is also focused in the

understanding of privacy protection in a scenario of

data provision. The scenario introduced the idea that

when data is voluntarily provided to a data collector,

the user can decide on a level of privacy protection

that is given to that data. Here, the participants

interpret privacy protection as anonymization and the

level of privacy protection as proportionate to the k-

anonymity in a data set. This idea is also then merged

into the visual representation and control elements for

privacy protection. The participants wish to see the

group of people among which they would not be

distinguishable anymore.

This focus on the concept of k-anonymity may

show that this is the mental model the participants

have for privacy protection. On the other hand, the

discussion could also have taken this focus, because

no alternative concept was available and this one was

easy to relate to. In such a qualitative approach, the

framing due to the questions asked by the interviewer

as well as the answers of other focus group attendees

influence the participants. Thus, we cannot claim that

this is a pre-existing mental model.

Other concepts, like privacy protection as a

barrier or lock (cf. Dourish et al. 2003, Asgharpour et

al. 2007), were not well applicable in the scenario

because they offer only two states: protected or not.

When given the choice, the participants wanted more

control and, thus, more nuances or gradations in the

setting. Still, the models of physical privacy

protection by a fence, wall, or padlock are matched

by the initial evaluation of some participants, namely

that privacy protection is binary, and were initially

preferred by some participants. In other privacy

contexts, physical privacy, psychological, and social

privacy, protective means are often binary, such as

shutting a door or refusing to speak to a person. These

measures have been known to people for centuries.

But the complexity of the online world is still new and

always changing. The idea of scalable privacy

protection may not be obvious to users and, hence,

does not fit existing mental models.

Within the research project myneData, the idea of

adjustable privacy protection is one central element.

If it is indeed the case that the only existing mental

models of privacy protection are binary, these models

cannot be used. To the concept of k-anonymity –

IoTBDS 2018 - 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

92

visualized with a group of people – all participants

were able to relate. But as we have seen, the concept

may not be understood correctly by all and would

need a good textual explanation to avoid or remove

ambiguity.

That all participants were able to answer at least

one third of the questions in the privacy literacy test

correctly shows that we did not include participants

with very little knowledge about online privacy

aspects in our sample. We saw differences in the

understanding of the concept privacy protection and

also of the concept of anonymity. The participants in

our sample could relate to the concept of k-anonymity

in most parts. But the question remains, whether all

users, including those with low technical knowledge,

can do so. Concerning the intended myneData

platform, every user, independent from the technical

knowledge, is meant to be able to interact with the

interface. Therefore, a universally comprehensible

visualization is needed that is intuitively understood,

or at least simply learnable for users with little as well

as for users with much knowledge and understanding

about the technical background. More details can

always be given in a multi-layered information

design, e.g., with using tool-tips. But every user

should be able to understand the general concept

without reading background details. Mental models

need not cover the complexity of the concept, after all

they are simplified representations and can, thus, be

imperfect (Jones et al. 2011). Hence, even if they do

not cover the area of adjustable privacy, locks, walls,

and fences are good representations for protection in

other digital contexts.

The relatively small sample size and way of

participant acquisition does not lend itself to

generalizability of the results. However, it was useful

to gain insights into possible factors and ideas

concerning privacy and privacy protection that should

be validated with a quantitative study.

In the context of the research project myneData

and the development of a user-friendly interface for

adjustable privacy protection, perhaps a conjoint

study to understand which aspects have the most

influence on privacy protection behavior might yield

good results as the visual representation of different

privacy aspects have to be incorporated into the actual

study. Moreover, mental models could differ between

users. A quantitative analysis whether mental models

differ between user groups, for example, depending

on privacy knowledge, internet experience, or age,

could provide interesting insights and enhance the

results by Coopamootoo & Groß (2014a).

The present study again showed that privacy

protection is perceived as complex and exhausting.

Most users are concerned about their online privacy

and try to protect themselves – but they do not know

how to accomplish that. Comprehensible measures

for protecting privacy and easy to use interfaces are

needed that speak the users’ language and adopt

users’ mental models.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants of the focus groups and

interviews for their willingness to share their thoughts

and opinions about privacy and its protection. We

also thank Benedikt Allendorf for his research

support. Parts of this work have been funded by the

German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF)

under the project MyneData (KIS1DSD045).

REFERENCES

Asgharpour, F., Liu, D. & Camp, L.J., 2007. Mental Models

of Security Risks. In S. Dietrich & R. Dhamija, eds.

Financial Cryptography and Data Security: 11th

International Conference, FC 2007, and 1st

International Workshop on Usable Security, USEC

2007. Revised Selected Papers. Berlin, Heidelberg:

Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 367–377.

Burgoon, J., 1982. Privacy and communication. Annals of

the International Communication Association, 6(1),

pp.206–249.

Camp, J., Asgharpour, F. & Liu, D., 2007. Experimental

Evaluations of Expert and Non-expert Computer Users’

Mental Models of Security Risks. Proceedings of WEIS

2007.

Camp, L. J., 2009. Mental models of privacy and security.

IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 28(3),

pp.37–46.

Coopamootoo, K.P.L. & Groß, T., 2014a. Mental Models:

An Approach to Identify Privacy Concern and

Behavior. Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security

(SOUPS).

Coopamootoo, K.P.L. & Groß, T., 2014b. Mental Models

for Usable Privacy: A Position Paper. In T. Tryfonas &

I. Askoxylakis, eds. Human Aspects of Information

Security, Privacy, and Trust: Second International

Conference, HAS 2014, Held as Part of HCI

International 2014, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, June 22-

27, 2014. Proceedings. Cham: Springer International

Publishing, pp. 410–421.

Coopamootoo, K.P.L. & Groß, T., 2014c. Mental Models

of Online Privacy: Structural Properties with Cognitive

Maps. In Proceedings of HCI. pp. 287–292.

Courage, C. & Baxter, K., 2005. Understanding Your

Users: A Practical Guide to User Requirements

Methods, Tools, and Techniques, Amsterdam: Gulf

Professional Publishing.

Hidden within a Group of People

93

Culnan, M. J., & Armstrong, P. K. (1999). Information

privacy concerns, procedural fairness, and impersonal

trust: An empirical investigation. Organization

science, 10(1), 104-115.

Dourish, P., Delgado De La Flor, J. & Joseph, M., 2003.

Security as a Practical Problem: Some Preliminary

Observations of Everyday Mental Models. Proceedings

of CHI 2003 Workshop on HCI and Security Systems.

European Commission, 2015. Data protection

Eurobarometer.

Feinberg, J., 2014. Wordle. Available at: www.wordle.net.

Gentner, D., & Stevens, A. L. (2014). Mental models.

Psychology Press.

Grenier, R.S. & Dudzinska-Przesmitzki, D., 2015. A

Conceptual Model for Eliciting Mental Models Using a

Composite Methodology. Human Resource

Development Review, 14(2), pp.163–184.

Hsieh, H.-F. & Shannan, S.E., 2005. Three Approaches to

Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health

Research, 15(9), pp.1277–1288.

Jones, N. a. et al., 2011. Mental Model an Interdisciplinary

Synthesis of Theory and Methods. Ecology and Society,

16(1), pp.46–46.

Matzutt, R. et al., 2017. myneData: Towards a Trusted and

User- controlled Ecosys-tem for Sharing Personal Data.

In Maximilian Eibl & Martin Gaedke, eds.

INFORMATIK 2017, Lecture Notes in Informatics

(LNI). pp. 1073–1084.

Morgan, M.G. et al., 2002. Risk communication: A mental

models approach, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Motti, V.G. & Caine, K., 2016. Towards a Visual

Vocabulary for Privacy Concepts. Proceedings of the

Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual

Meeting, 60(1), pp.1078–1082.

Olson, J.R. & Biolsi, K.J., 1991. 10 Techniques for

representing expert knowledge. In Toward a general

theory of expertise: Prospects and limits. p. 240.

Prettyman, S.S. et al., 2015. Privacy and Security in the

Brave New World: The Use of Multiple Mental

Models. In T. Tryfonas & I. Askoxylakis, eds. HAS

2015. Springer International Publishing, pp. 260–270.

Raja, F. et al., 2011. Promoting A Physical Security Mental

Model For Personal Firewall Warnings. CHI 2011.

Sweeney, L., 2002. k-Anonymity: A Model for Protecting

Privacy. International Journal of Uncertainty,

Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems, 10(5),

pp.557–570.

Trepte, S. et al., 2015. Do People Know About Privacy and

Data Protection Strategies? Towards the “Online

Privacy Literacy Scale” (OPLIS). Springer

Netherlands, pp. 333–365.

Trepte, S. & Masur, P.K., 2016. Cultural Differences in

Social Media Use, Privacy, and Self-Disclosure.

Research report on a multicultural survey study,

Germany: University of Hohenheim.

Vervier, L. et al., 2017. Perceptions of Digital Footprints

and the Value of Privacy. In International Conference

of Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS

2017). SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology

Publications, pp. 80–91.

Wash, R., 2010. Folk Models of Home Computer Security.

Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS)

2010.

Zaunbrecher, B. et al., 2016. What is Stored, Why and

How? Mental Models and Acceptance of Hydrogen

Storage Technologies. In 10th International Renewable

Energy Storage Conference (IRES 2016). Energy

Procedia, 99, pp. 108-119.

Zeissig, E.-M. et al., 2017. Online Privacy Perceptions of

Older Adults. Human Computer Interaction

International (HCI) 2017.

Ziefle, M., & Bay, S., 2004. Mental models of Cellular

Phones Menu. Comparing older and younger novice

users. In S. Brewster & M. Dunlop (eds.). Mobile

Human Computer Interaction (pp. 25-37). Berlin,

Heidelberg: Springer.

Ziefle, M.; Halbey, J. & Kowalewski, S., 2016. Users’

willingness to share data in the Internet: Perceived

benefits and caveats. In International Conference of

Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (IoTBDS

2016). SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology

Publications, pp. 255-265.

IoTBDS 2018 - 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security

94