ReadAct

Alternate Reality, Serious Games for Reading-Acting to Engage Population and

Schools on Social Challenges

Marcelo Alves de Barros

1

, Valéria Andrade

2

, J. Antão B. Moura

1

, Laurent Borgmann

3

, Uwe Terton

4

,

Fátima Vieira

5

, Gabriel Cintra Alves da Costa

1

, Rafaela Lacerda Araújo

1

, Aline Oliveira Arruda

6

,

Sophie Naviner

7

and Jobson Silva

1

1

Systems and Computing Department, Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Brazil

2

Semiarid Development Center, Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Brazil

3

University of Applied Sciences Koblenz, RheinAhrCampus, Germany

4

University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

5

Universidade do Porto, Portugal

6

Master Program on Language and Learning, Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Brazil

7

Ecole de Hautes Etudes du Commerce-HEC Paris, France

uterton@usc.edu.au,vieira.mfatima@gmail.com, gabriel.cintra@ccc.ufcg.edu.br, rafaela.araujo@ccc.ufcg.edu.br,

alinearrudaufcg@gmail.com, sophie.naviner@hec.edu, jobson.silva@ccc.ufcg.edu.br

Keywords: Serious Games, Alternate Reality Games, Reading, Acting, Social Challenges.

Abstract: This paper presents a gamified empowerment approach to train future teachers. The approach aims to

innovate teaching strategies and to provide a system which motivates players to read and to apply acquired

knowledge towards actions to address social challenges within their community. The approach is supported

by an alternate reality serious game called “ReadAct” which blends reading instruction with opportunities to

act on social responsibility in the real world. Validation results are offered for experiments with the

ReadAct approach in different but related contexts of drama reading, environmental education and

introduction to computing. Results provide evidence that ReadAct motivates players (young readers) to

engage themselves and to attract their schools’ and families’ communities to act on social challenges. The

underlying challenges in the experiments are water conservation, urban violence and bullying at school. The

paper contributes to the literature on computer-based education by indicating how a ReadAct game may turn

the school community, where it is played out, into a community school with an integrated view of

academics and social services.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past, federal governments have had the

undisputed responsibility to resolve any serious

threats to society. In cases of earth quakes, flooding,

or terrorism, we still expect the state to come to the

rescue, and the heads of states “to find the right

tone” when they address the afflicted nation. The

government acts as this managerial monopoly

because it seems that in this battle, only the state has

sufficient power, infrastructure, resources, and

organizational authority to take the right decisions

and make a real difference. In these crisis scenarios

the population is mostly reduced to the role of

passive spectators where ordinary people tend to sit

back and observe. However, one can now read

stories about well-organized groups of ordinary

citizens who simply refuse to be reduced to

observers and, using social media, act to address

diverse problems, such as those discussed in

//chicagoscitizensforchange.wordpress.com.

Upon reading such stories, one may pose

intelligent questions like: Could such low-threshold

community networking also facilitate the

intercultural integration of refugees who have fled

from war zones or persecution and are now expected

to find a new orientation in their host countries? Or

could such spontaneous, private engagement of

citizens and communities in low-cost, networking

238

Barros, M., Andrade, V., B. Moura, J., Borgmann, L., Terton, U., Vieira, F., Cintra Alves da Costa, G., Lacerda Araújo, R., Oliveira Arruda, A., Naviner, S. and Silva, J.

ReadAct.

DOI: 10.5220/0006691102380245

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2018), pages 238-245

ISBN: 978-989-758-291-2

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

solutions be harnessed to tackle wider, more

complex social challenges - such as the spread of

endemic diseases (e.g., Zika, Dengue and Yellow

Fever), local water shortages, gender violence, or

even racism? In the past, these societal challenges

have been traditionally and mostly addressed by

governments and scientists, with little engagement

of the population, schools, or universities, even in

places which are near and dear to populations and

students within their own communities (see for

example, Eggers and MacMillian, 2013). This paper

attempts to provide preliminary answers to questions

like these – to the second one in particular.

The approach proposed here assumes that

community members have three major resources that

could be put to use in dealing with a critical social

scenario in their region:

1) Insider knowledge - about the scenario itself

and appropriate solutions (e.g. from previous

experiences of similar crises in the same region);

2) Energy for social activity - to help solve

problems (when they or their communities are

afflicted themselves); and,

3) Large numbers of flexible actors who could be

fielded to alleviate symptoms or implement

solutions - as compared to government agents who

get paid by the hours and are subject to their strict

work regulations.

However, in spite of the magnitude and cost of

the social challenges which modern communities

face, their members often do not display initiative:

these powers appear to be latent, and have yet to be

harnessed and applied efficiently. One effective way

to change attitudes is to educate multipliers to assess

a crisis and immediately initiate solutions within

their communities. Instead of passively observing a

crisis develop and leaving it to be resolved by the

centralized authorities, multipliers need to read and

act (“ReadAct”), to do research about the problems

and then motivate themselves and others into action.

Reading and writing form the foundation that is

the base of any educational process for the

empowerment of both individuals and entire

communities. An educational approach that couples

reading to acting (e.g. teaching reading at school is

made relevant to the daily experiences students have

in the community), could prove effective and

efficient in helping communities address their own

social challenges. At the same time, an approach

which motivates youngsters to read about local

challenges could also help address a more general

dilemma: young people’s growing incapability or

unwillingness to read literature.

Data from the 2015 Program for International

Students Assessment (PISA) indicated that 20% of

youngsters averaging 15 years in age fail to reach

minimal reading capacity in OECD countries

(Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development). The situation in Brazil – where part

of the research reported in this paper was carried out

is no exception (FAILLA, 2016). Even in Germany

(Kote, Lietz and Lopez, 2005) where the results of

the present research are planned to be implemented

in the future, the percentage of 15-year-olds without

minimal reading capacity is reported to be as high as

16%. These students do not reach level 2 (“baseline

level of reading” which enables a person to lead a

normal life and participate in society) - a statistic

which must alarm teachers and authorities in atleast

one of the richer countries of the OECD. These

findings can be partly explained with a high influx

of refugees in Germany because the majority of

them have not even studied in the regular school

system yet. However, once they begin, many of

them will still fall short of the baseline level of

reading simply because they have not had much

contact with the German culture and language yet,

even if in their countries of origin they may have

belonged to the 80% of the population with enough

reading skills to lead successful lives. It is thus

important to empower students and teachers to

develop and improve their reading abilities by

motivating them to act on solutions to problems in

their own social context.

This paper presents a gamified empowerment

approach to train future teachers. This approach

aims to innovate teaching strategies and provide a

system to motivate young readers to apply acquired

knowledge towards acting on social challenges

within their community. The approach is supported

by an alternate reality serious game (called

“ReadAct”) which blends reading instruction with

opportunities to act on social responsibility in the

real world. Players use reading to investigate

problems and to do research in order to find

resolutions to real challenges to the community. It is

expected that ReadAct will motivate players to read

because they are interested in real-life challenges to

their own community and are additionally motivated

by new information technologies such as serious

games.

The ReadAct approach was successfully tried out

in a serious game concerning water conservation,

called AquaGuardians (Barros et al. 2017). In the

present paper, however, the approach is described in

more detail and elevated to a meta-level in order to

promote a more general, common design in the

ReadAct

239

development of related serious games. The paper

reviews the ReadAct approach in three different, but

related contexts, to allow for a wider range of

preliminary validation scenarios:

1) Teacher training for drama reading

2) Environmental education

3) Introduction to computing

The research involved more than 160

stakeholders. Results indicate that the ReadAct

approach may contribute to the improved design of

serious games as support tools for reading education

motivated by social responsibility and serious

games.

Section 2 discusses related work. Section 3

describes the ReadAct approach in detail and how it

was implemented in practice. Section 4 presents

results from validity experiments for the proposed

approach, and Section 5 offers analyses and

considerations on design aspects and on potential

applications of the ReadAct approach to social

challenges in the areas of intercultural integration of

refugees in our societies.

2 RELATED WORK

This work relates to theatrical reading of multimedia

texts to “transform readers into actors.” “Dramatic

Wednesdays” is a Literature and Scenic Arts project

at the University of Brasília, Brazil where

participants proceed from individual and silent

reading to collective reading using oral and body

languages. Readers and spectators may take part in

the play “to reflect on the scenic reading towards

transforming society” (Gomes, 2012). Similarly, the

“Reading in Scene” from the Federal University of

Alagoas, Brazil reading is taken up as a performance

activity through which the reader, in contact with the

intended sensorial interactions embedded in the

written word, experiences possibilities of education,

transformation and reconfiguration of perceptions

about him/herself and about the world (Oliveira,

2010). These projects however, do not address

specific social challenges, and they are intentionally

derived actions coordinated with the support of a

serious game as the ReadAct approach does. Serious

games use intrinsic incentives – such as conquests,

social responsibility and ability building – and

extrinsic incentives – such as points, proactive

feedback and (game proficiency) levels – to

maintain players’ interest in learning a given content

and to motivate them to attain a desired proficiency

level in the activities that may be proposed in the

game story (Kankaanranta; Neittaanmki, 2008).

Alternate reality games can aim to make the player

cross borders of the magic circle of the game

experience and bring the player to act in some useful

way in the real world (Huizinga, 2014). Such games,

as proposed by Jane McGonigal (2011), explore

everyday experiences and cultural settings.

However, these approaches often do not incorporate

new teaching-learning management paradigms and

tools to engage players in addressing community

challenges despite breaking new ground in game

research, Other games, such as AquaGuardians

(Barros et al., 2017), do address complex, important

social problems and also use “reading or writing

missions” to educate players on a given social

problem (sustainable water management, in this

case). Here, the ReadAct approach is used to define

reading missions in serious, alternate reality games

which may be applied to motivate engagement of

communities to address challenges in a wider

spectrum of social contexts.

3 THE READ & ACT APPROACH

ReadAct is an innovative approach to teaching and

learning that uses alternate reality and serious games

in schools, including the reading and production of

theatrical texts in order to develop reading and

writing abilities, improve performance in

interdisciplinary subjects, and increase engagement

of teachers and students in social actions within their

students’ communities.

ReadAct games revolve around missions which

are run partly in the virtual world and are made up in

the context of the reference story (i.e.: gameplay in

computers and on mobile devices); and partly in

three real world settings where students can practice

applying knowledge acquired from curriculum and

theatrical texts to address real world social

challenges within their communities. There are 3

performing stages:

1) At school (educational space)

2) On the Web (online game space), and

3) In the community (real world space).

As the game proceeds, players’ (students’)

awareness of the social challenge of interest spirals

up like in a vortex whose height and width represent

the accumulation of knowledge and the potential

benefit for the community (Figure 1).

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

240

Figure 1: ReadAct spiral for growing knowledge (z axis),

organization (stage size) and initiative for action (x, y).

By performing on the three stages - which also

represents the players’ world (school, virtual world

in the web, and community), knowledge about the

social challenge of interest is built by the readers-

players through educational ReadAct missions under

the leadership of a mentor who is meant to inspire

others. This knowledge will be successively

converted and articulated to become part of the

knowledge base of each player. The spiral starts

again after being completed once (in different

missions in the game) at higher levels of players’

capacity, amplifying the application of acquired

knowledge about the social challenge of interest to

society’s other “problematic” areas. In these

progressive cycles of the spiral, with knowledge

conversion and multiplication, players (students who

are changing into social actors) teach new players

and function as multipliers and mentors.

On stage, players, presented with a sequence of

situations previously programmed by the teacher,

play the role of persons who had problematic

experiences related to the social challenge of

interest. Orally or in writing they must describe their

experiences to other groups of actors of the same

situation, to gain intercultural awareness and

collaboratively find a solution to a social issue by

applying information from the curriculum and from

the theatrical text used to seed missions of the game.

Missions cover specific, interdependent activities

of leadership, research, teaching and extension for

the creation of multimedia textual work pieces on a

social theme whose value is acknowledged by the

game community. These work themes come out of a

knowledge management experience of a small group

and are based on the reading of a multimedia

document (text, audio, video, etc…) that relates to a

social challenge of players’ interest. The player or

the group of players may add to the document,

becoming its co-author. Missions require theatrical

readings when the player or group must

contextualize the contents and recreate the document

(writing assignments).

A set of missions defined by a specially

appointed tutor or by government (social) agents,

corresponds to one ReadAct session. A ReadAct

session may be divided into sub sessions to

contemplate the priorities in the school curriculum

and operating agendas and thus synchronizing with

cultural agendas of players’ communities and with

interested government agencies’ agendas.

3.1 Meta Game and Major

Components

ReadAct is conceived as a design framework for

serious games or as a meta-game which in the hands

of the teacher transforms itself into a specific,

alternate reality serious game addressing community

challenges. In practice, the approach consists of

three major, interacting components: a gamified

Mobile App, a Web Georeferenced Information

System (GIS), and a Marketplace.

A ReadAct game is played on two

complementary technological platforms. On the

Mobile Platform, the players have 5 resources do

play with:

1) Alternate Reality Game Missions (ARG

Missions) where they may geo-reference their real-

world activities using the GPS facility and

registering and uploading multimedia files,

2) Read-Write tools where they may report on

their reading and writing missions in the real world,

3) Theme oriented mini-games,

4) Quizzes, and

5) Online marketplace to commercialize works

they coauthored in the missions.

On the Web Platform, teachers, specially

appointed student-tutors and government agents who

play the game as instructors or tutors may:

1) Assign missions to students in the virtual and

real worlds;

2) Access a control panel for monitoring (with

graphs, statistics or reports on the gaming

experience);

ReadAct

241

3) Access a geo-referenced information system

to manage students’ activities and teaching/learning

indicators;

4) Use pedagogical tools to train players;

5) Be a part of a closed ReadAct social network

or connect to major open networks such as Facebook

and Instagran or,

6) Take part in transactions in the marketplace.

The integrated marketplace may help

sustainability by merchandising ReadAct game

artifacts; it also offers players a venue for

commercializing co-authored works with points or

virtual money awarded for accomplished missions.

Virtual money may be exchanged for real goods

(e.g.: a ReadAct T-shirt) or services (a movie ticket)

in the real world with the help of participating

ReadAct business partners. As partners contribute to

the expansion and sustainability of a ReadAct game

by providing goods and services in the marketplace,

they also improve their social responsibility image

as perceived by the game community.

For the initial versions of the ReadAct games

considered here, the mobile component was

implemented for the Android platform, with Google

maps native GPS and MySQL database. The Web

component was implemented as a Restful Web

Service using JAXRS and/or Unity. For simplicity

of these initial versions, the marketplace was

implemented offline and it was not integrated to the

other components.

3.2 A ReadAct Game Example

Figure 2 shows some mobile app screens of the

ChangeTrees game which follows the ReadAct-

functioning principles to engage tutors and students

of computer science in activities to prevent urban

violence.

By completing each of the three steps needed to

advance to the next level of the spiral, players

elevate themselves by readings on topics such as

mathematics and literature (height of the spiral - z

axis) and the level of impact that their organization

and initiative have on the urban violence social

problem (vortex diameter – axes x and y).

The game starts with the teacher or master tutor

facilitating the group processes of

1) Selection of an existing social challenge (e.g.

urban violence),

2) Creation of groups of readers,

3) Definition of success indicators and

4) Definition of the pedagogical project.

Figure 2: ReadAct approach-based ChangeTrees game

mobile app screens (available from Playstore).

Theatrical readings follow under the lead of the

appointed group tutor (one of the group’s students).

The group tutor also supervises research on the

chosen topic, training which the group may need and

interactions with the target audience of the social

actions associated with the game missions (the local

community outside the school).

Examples of dynamics and characteristics such

as missions for other ReadAct games, may be found

in (Barros et al., 2017). For instance in a ReadAct

game for water preservation and management, a

mission may include challenges to go out and

register examples of water wastage or saving or a

combination of all that (a notification of a problem

in need of attention).

In any ReadAct game, missions involve

creativity in multimedia reading-writing, using an

existing multimedia product (theme mini-games, a

quiz challenge, a leader board game or other digital

game), or the teacher may also embed teaching-

learning indicators and assign weights to work to be

produced by the students according to objectives of

the pedagogical process, and manage these

indicators by means of graphs, statistics and reports

that support continuing evaluation and planning of

this process.

4 PRELIMINARY VALIDATION

The ReadAct approach and associated gamification

were subject to preliminary validation studies in a

setting of teacher education in 3 contexts at the

Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG):

Edgies – teacher training in the graduate program of

literature and pedagogy; AquaGuardians –

environmental education in the computer science

undergraduate program; and, ChangeTrees –

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

242

introduction to computing and literature in the

Computer Science tutoring program and introduction

to programming in the electrical engineering

undergraduate program.

In the Edgies game, players chose to work on the

problem of violence at school (bullying). In

AquaGuardians players chose to work on the

problem of water waste. In ChangeTrees players

chose to work on the problem of urban violence.

In this context “teacher” is any person trained in

the ReadAct approach to be a “volunteer tutor”. In

this sense, a teacher may be any professional trainer,

including those in the area of education or already

certified teachers themselves. This situation is

representative of many real scenarios where

professionals from different areas volunteer to help

with a solution to a social problem whose

complexity may increase due to cultural barriers or

speech or writing limitations in a given language.

The validation studies discussed here are

preliminary and based on the principles of

experiment observer reliability (LITWIN, 1995).

The studies were carried out to verify whether

ReadAct would positively impact for the two

following success indicators:

A) Level of reading motivation and

B) Engagement in social activities related to

violence at school (bullying), to water waste and to

urban violence.

Various validation experiments were performed

with a total of 145 “teachers” (19 to 35 years old,

23.5% male and 76.5% female) from primary and

secondary schools for a duration of 4 months in

2017. Nineteen were “teachers” of Portuguese (13

played at UFCG and 6 played at primary and

secondary schools in the city of Sumé, state of

Paraíba, Brazil); 32 “taught” environmental

education at UFCG; and, 94 were teachers of

introduction to computing (31 played at the tutored

education program in the computer science course at

UFCG and 63 in the electrical engineering course at

the same university); and 2 functioned as “teacher

training agents” in preparing 4 missions in the real

world besides text, audio, video and HQ assignments

and orchestrating social actions in the players

communities.

All the players played the same ReadAct game

composed by 4 read-writing-acting missions

embedded in the 3 games (Edgies, AquaGuardians

and ChangeTrees). All participants in the

experiment were trained in the 5 ReadAct resources

and facilities available in the 3 used games (Edgies,

AquaGuardians and ChangeTrees) to play the

mobile or the Web app of each game as student or

teacher. Only the multimedia seed texts were

different. Each game was played for 4 weeks with

players free to play the theatrical mini-games but

obliged to run the 4 real-world missions together

with their students at the schools where they work.

Figure 3 shows scenes of ReadAct being played at

schools.

Figure 3: Playing ReadAct games.

After the intervention period at the schools

revolving around the missions, the participants were

asked to opine on the influence of each of the 5

resources and facilities of ReadAct game embedded

in the 3 games on two indicators. The considered

indicators were:

A) Influence of the 5 ReadAct games’ resources

on increased motivation to (continued) reading and

B) Influence of the 5 ReadAct games’ resources

on increased motivation to initiate social activities in

the real world by using knowledge embedded in

theatrical texts they had read.

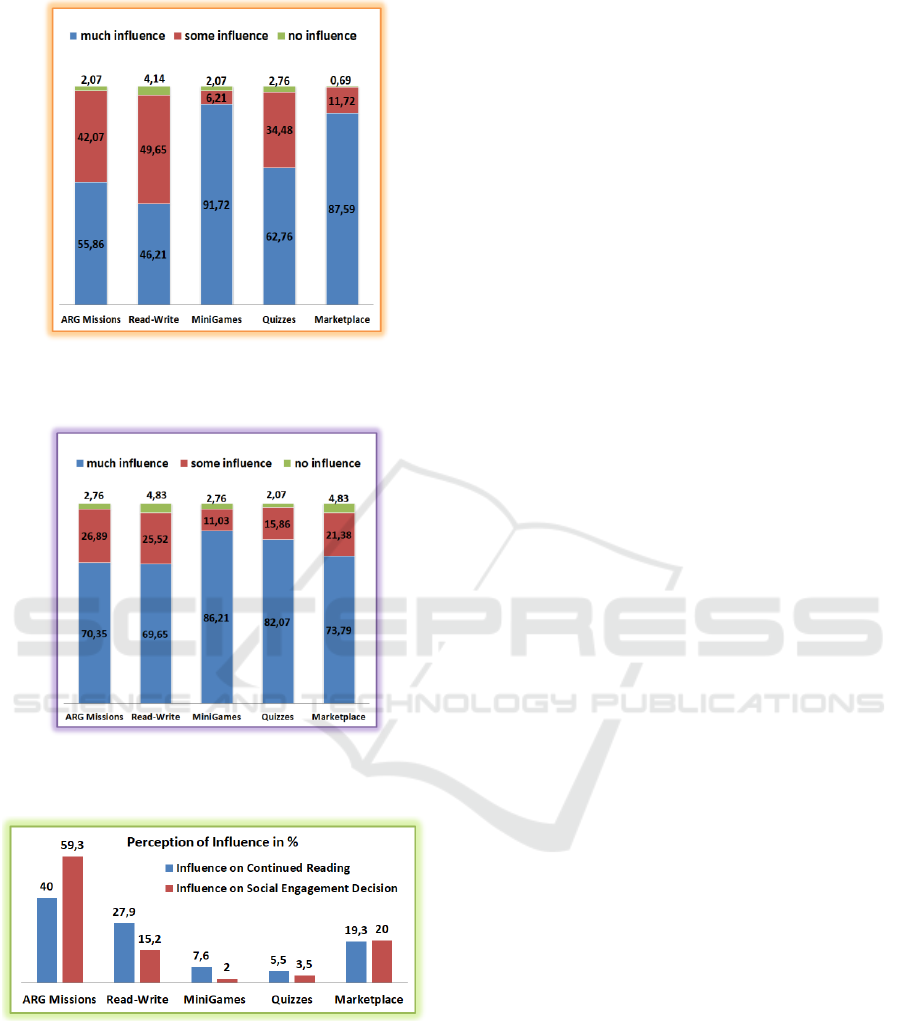

Graphs 1, 2 and 3 present results. On the

average, 97,65% (={[(42,07+55,86) + (49,65+46,21)

+ (6,21+91,72) + (34,48+62,76) +

(11,72+87,59)]/5}) of the overall opinions in Graph

1 are that the 5 resources and facilities of the

ReadAct game (much or somewhat) influence the

increase of players’ motivation to (continued)

reading. From Graph 2, the overall average of

96,56% (={[(26,89+70,35) + (25,52+69,65) +

(11,03+86,21) + (15,86+82,07) + (21,38+73,79)]/5})

of the opinions point towards the conclusion that the

5 resources and facilities of the ReadAct game are of

much influence on players’ decisions to engage in

real-world social activities (utility).

Graph 3 illustrates the perceived contribution of

the five ReadAct resources and facilities to the

results in Graphs 1 and 2. The ARG Missions

facility was considered by 40 % of players as having

the most influence on the first indicator above, and

by 59,3 % of players as having the most influence on

the second one.

ReadAct

243

Graph 1: Evaluation results for indicator A: motivation to

(continued) reading.

Graph 2: Evaluation results for indicator B: motivation to

initiate social activities in the real world.

Graph 3: Ranking influence of the 5 ReadAct resources

and facilities (% of players’ evaluation).

Each of the ReadAct games examined here is in

its first limited version (e.g., it has no embedded

marketplace facility) and was applied to one context

only. Consequently, the validation results discussed

in this section are still preliminary and limited in

scope. Participating validators, however, provide

evidence the ReadAct approach seems to motivate

players to engage in actions to deal with social

challenges. As such, one may say that such evidence

supports “face validity” of the approach (Gravetter

and Forzano, 2012).

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented the ReadAct approach to build

alternate-reality serious games which blend tutorial-

based education and theatrical reading (and writing)

of multimedia contents about a given social

problem. The approach seeks to empower teachers

and students of a school to take individual or

collective action to solve the given problem in the

context of their community. Essentially then, a

ReadAct game aims at turning the school

community into a community school with an

integrated view of academics and social services.

Besides gamification techniques of conventional

games that are used in its mobile app, the proposed

ReadAct game also offers a Web geo-referenced

information system for teachers and specially

appointed tutors to create, dispatch and manage

geo-referenced missions for the players (individuals

or groups of students) in the real world in addition

to reading assignments that explore principles of

crowd sourcing, utopia, incentives engineering,

knowledge management, trust verification, and

entrepreneurship and e-commerce (as implemented

in the marketplace component).

Validation studies were carried out with 3

ReadAct games (Edgies, AquaGuardians and

ChangeTrees) over a period of 4 months, involving

145 participants. Results were collected through a

post-use survey and suggest that the ReadAct

games’ facilities and resources motivate players to

transcend their original roles as students, teachers

and appointed tutors towards the role of voluntary

social actors, and they also positively influence

success indicators defined for reading and social

activities. It should be noted however, that the

presented results serve only to support face validity

– i.e., that the approach seems to spur desired social

actions; further work is required to really ascertain

that the approach will be useful in spurring social

activism of the type required by the specifics of

crises or problems at hand.

Ongoing work includes experiments with longer

term usage of ReadAct games, larger player

communities, and some selected social challenges in

the areas of violence against women, child obesity,

homophobia, dengue fever, and unemployment, to

produce statistically more significant results and to

CSEDU 2018 - 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

244

evaluate influence on other indicators related to

respective social problems. The University of

Applied Sciences Koblenz, RheinAhrCampus has

expressed the wish to try out the ReadAct approach

for their courses in Social Entrepreneurship and

wants to co-author a specially designed serious game

for the intercultural integration and inclusion of

refugees in rural communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the students and teachers of the

graduate programs of literature and pedagogy of

UFCG, and the Secretariat of Education of the cities

of Campina Grande and Sumé for their active

participation as well as Katherine Denning from the

University of Applied Sciences Koblenz for proof-

reading. They also thank the Brazilian National

Water Agency (ANA), the Brazilian Fund for

Education Development (FNDE), the Coordination

for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel

(CAPES), Paraiba state's Foundation for Research

Support (FAPESQ-PB), and the Ministry of

Communications for the financial support to this

project.

REFERENCES

Barros, M. et al., AquaGuardians - A Tutorial-based

Education Game for Population Engagement in

Water Management, In Proceedings of the 9th

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education - Volume 2: CSEDU 2017, 146-

153, 2017, Porto, Portugal

Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon

Books, 1949.

Candido, Antonio. O direito à literatura: Vários escritos.

4a. ed. reorganizada pelo autor. São Paulo: Duas

Cidades, 2004. p. 169-191.

Castellani, et al. Game Mechanics in Support of

Production Environments. CHI’13, ACM Press, 2013.

Delwiche, A. Massively multiplayer online games

(MMOs) in the new media classroom. Educational

Technology & Society, 9 (3), 2006, p. 160-172.

Eggers, W.D. and McMillan, P. Government Alone Can’t

Solve Society’s Biggest Problems, Harvard Business

Review, Economy, September 2013.

https://hbr.org/2013/09/government-alone-cant-solve-

societys-biggest-problems. Accessed 1st January

2018.

Failla, Zoara. Leitura dos “retratos”: o comportamento

leitor do brasileiro. In: _. Retratos da leitura no Brasil

3. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São

Paulo, 2012. p. 19-54.

Geraldi, João Wanderley. Portos de passagem. 4 ed. São

Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2003.

Gomes, André Luiz. “Lei(a)tores” em processo coletivo e

colaborativo no Quartas Dramáticas. Pitágoras, 500 –

V. 2, abr. 2012. Disponível em:

http://www.publionline.iar.unicamp.br/index.php/pit50

0/article/viewFile/21/44. Acessed: 30 December 2017.

Gravetter, F. J. and Forzano L. A. B. Research Methods

for the Behavioral Sciences. 4th edition. Belmont, CA:

Wadsworth 78 (2012).

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: Homo ludens; a study of

the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press,

1955.

Kankaanranta, M. H. and Neittaanmki, P. Design and Use

of Serious Games, Springer, 2009.

Koch, Ingedore. Inter-ação pela linguagem. São Paulo:

Contexto, 1992.

Kote, D., Lietz, P. and Lopez, M. M. Factors Influencing

Reading Achievement in Germany and Spain:

Evidence from PISA 2000, International Education

Journal, v6 n1 p113-124 Mar 2005.

Lajolo, Marisa. O texto não é pretexto. In: Zilberman,

Regina (org.). Leitura em crise na escola: as

alternativas do professor. Porto Alegre: Mercado

Aberto, 1988. (In Portuguese)

Litwin, M. How to Measure Survey Reliability and

Validity. Los Angeles: Sage, 1995.

McConigal, Jane. Reality Is Broken. Why Games Make

Us Better and How They Can Change the World.

Penguin Press HC, 2011.

More, Thomas. (1985). Utopia. Dent, Everyman [1516].

Oliveira, Eliana. Leitura, voz e performance no ensino de

literatura. Signótica, v. 22, n. 2, 2010. From

http://www.revistas.ufg.br/sig/article/view/13609/8736

Accessed 10 October 2016.

Pennac, D. Como um romance. Tradução de Leny

Werneck. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1993.

Petit, Michèle. A arte de ler: ou como resistir à

adversidade. São Paulo: 34, 2009.

Rojo, R. H. R.; Cordeiro, G. S.; Schneuwly, B.; Dolz, J.

(Orgs.). Gêneros Orais e Escritos na Escola. Tradução

de trabalhos de Bernard Schneuwly, Joaquim Dolz e

colaboradores. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2004. v.

1.

Rouxel, Annie. Ensino da literatura: experiência estética e

formação do leitor (sobre a importância da experiência

estética na formação do leitor). In: ALVES, José

Hélder Pinheiro (org.). Memórias da Borborema 4:

discutindo a literatura e seu ensino. Campina Grande:

ABRALIC, 2014. p. 19-35.

Stephani, Adriana D.; Tinoco, Robson C. A formação dos

professores mediadores de leitura literária: os desafios

atuais. Anais. Simpósio Internacional de Ensino da

Língua Portuguesa-SIELP. V. 3, N. 1. Uberlândia,

EDUFU, 2014. Available from: http://www.ileel.ufu.

br/anaisdosielp/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1045.pd.

Acessed: 25 March 2016.

ReadAct

245