Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology

for Enterprise e-Recruitment

Saleh Alamro, Huseyin Dogan, Deniz Cetinkaya and Nan Jiang

Faculty of Science and Technology, Bournemouth University, U.K.

Keywords: Enterprise Recruitment, Problem Definition, e-Recruitment.

Abstract: Internet-led labour market has become so competitive forcing many organisations from different sectors to

embrace e-recruitment. However, realising the value of the e-recruitment from a Requirements Engineering

(RE) analysis perspective is challenging. The research is motivated by the results of a failed e-recruitment

project as a case study by focusing on the difficulty of scoping and representing recruitment problem

knowledge to systematically inform the RE process towards an e-recruitment solution specification. In this

paper, a Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model (POCM) supported by an Ontology for Recruitment Problem

Definition (Onto-RPD) for contextualisation of the enterprise e-recruitment problem space is presented.

Inspired by Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), the POCM and Onto-RPD are produced based on the

detailed analysis of three case studies: (1) Secureland Army Enlistment, (2) British Army Regular

Enlistment, and (3) UK Undergraduate Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS). The POCM

and the ontology are demonstrated and evaluated by a focus group against a set of criteria. The evaluation

showed a valuable contribution of the POCM in representing and understanding the recruitment problem

and its complexity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recruitment is a key strategic opportunity for

organisations to achieve a competitive advantage

over rivals (Bowen and Ostroff, 2004; Carless and

Wintle, 2007). Given talent is rare, valuable,

difficult to imitate, and hard to substitute,

organisations that better attract this talent to fill their

job vacancies should outperform those that do not

(Ray et al., 2007). Recruitment is the practice of

attracting sufficient numbers of qualified individuals

on a timely basis to fill job vacancies within an

organization (Ahamed and Adams, 2010). It ensures

the initial high quality abilities of recruits necessary

for work performance (Rynes and Cable, 2003). It

also supports a balanced diverse set of recruits to

meet organisation’s strategic, legal and social goals

in regards to the demographic composition of its

workforce (Gatewood et al., 2008).

The internet-driven global labour markets

become very competitive due to higher educational

level of the new generations, strong economic

situations and low unemployment rates (Tresch,

2008; Pfieffelmann et al., 2010). This, in turn, puts a

great deal of pressure on organisations from

different sectors to change their traditional

recruitment practices towards more innovative, high-

quality, customised, and timely e-recruitment

solutions (Pfieffelmann et al., 2010). In the military

sector, for instance, the migration from old

compulsory military recruitment to an all-volunteer

force relying on labour market has increasingly

pushed the military organisations to get into the

continuum (Tresh, 2008; Smaliukienė and

Trifonovas, 2012). E-recruiting is defined as any

recruitment practice that an organization conducts

using web-based solutions (Kim and O’Connor,

2009). Despite the different methods of e-recruiting,

web recruiting (i.e. use of corporate web site) is the

most commonly used e-recruiting method (Ahamed

and Adams, 2010). E-recruiting can bring value for

organisations including being reliable in attracting a

diverse and qualified group of job seekers, agility in

filling vacancies, cost-effectiveness, rapidly

response to job seekers’ changing needs and market

opportunities, and flexibility in normal and

exceptional circumstances (Alamro et al., 2015).

The current maturity of information and

communication technologies (ICTs) and the recent

developments in design processes have ensured a

280

Alamro, S., Dogan, H., Cetinkaya, D. and Jiang, N.

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment.

DOI: 10.5220/0006702902800289

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2018), pages 280-289

ISBN: 978-989-758-298-1

Copyright

c

2019 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

relatively simple and reliable transforming of the

conventional recruitment practice into e-recruitment

solution (Smaliukienė and Trifonovas, 2012).

However, to be innovative, the focus should be

shifted from the e-solution space into the problem

space where the desired effects (i.e. requirements)

that an organisation wishes to be brought by the e-

solution in the recruitment practice exist (Bray,

2002). With the help of Requirements Engineering

(RE), the RE activities of the e-solution must be

anchored to the domain knowledge of real-world

recruitment problem so that the quality of the e-

solution to be delivered can then be analysed

(Martin and Sommerville, 2004; Siegemund, 2014).

This front-end part of RE is called problem

definition (Jackson, 2001; Fouad, 2011). However,

in large-scale, trans-national and multi-

demographical organisations that are engineering-

focused and need reliable and long-lasting e-

solutions, the problem definition is very complex

and prone to failure (Kossmann and Odeh, 2010;

Siegemund, 2014). The research was originally

driven by the challenges faced in realising the value

of a real e-recruitment project from the military

sector referred to as Secureland Army Enlistment.

Three main challenges that are related to some

knowledge gaps in the research literature can be

summarised as:

The difficulty in scoping recruitment problem

(Saks, 2005; Breaugh, 2012);

The difficulty in representing and

understanding of real-world recruitment

problem (Ployhart, 2006; Gatewood et al.,

2008); and

The difficulty in systematically transforming

the problem domain knowledge into the

specification of e-recruitment (Martin and

Sommerville, 2004; Siegemund, 2014).

The practical problem addressed in this paper is

that the ill-representation and understanding of

recruitment problem impedes the realisation of the

value of e-recruitment. Therefore, the paper

proposes a Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model

(POCM) for conceptualising the recruitment

problem space from an enterprise perspective

supported by an Ontology for Recruitment Problem

Definition (Onto-RPD). During this study, three case

studies, including the Secureland Army Enlistment,

are analysed, and various problems are identified to

develop the conceptual model and the corresponding

ontology. This work provides a valuable

contribution into the understanding of recruitment

problem from different perspectives, and can deliver

guidance in a systematic manner to inform the

requirements elicitation and analysis towards e-

recruitment solutions.

The paper is organised as follows: this section

presents an introduction to the research study. The

literature review and background information are

presented in Section 2. The case studies are

explained and analysed in Section 3. Based on these

case studies, the POCM and Onto-RPD are proposed

in Section 4. The integration of the model into the

recruitment RE process and the results are discussed

in Section 5. Finally, conclusions are drawn and

future work is suggested in Section 6.

2 RECRUITMENT AND

e-RECRUITMENT

A great deal of research from both Human

Resources (HR) and Industrial and Organisational

(I/O) psychology domains has been conducted to

define recruitment. However, there has been no

consensus on its definition. Randall (1987) states

that recruitment is “the set of activities through

which the people and the organisations can select

each other based on their own best short and long

term interests”. This definition highlights

recruitment from the perspectives of the two key

players: organisation (i.e. employer) and people (i.e.

job seekers). However, from an organisation-based

perspective, Barber (1998) defines recruitment as

“the practices and activities carried on by the

organization with the primary purpose of identifying

and attracting potential employees”. He delineated

three phases of recruitment: (a) generating

applicants, (b) maintaining applicant status, and (c)

influencing job choice decisions.

Looking to recruitment from a broad sense,

Philips and Gully (2015) define strategic recruitment

as “the practices that are connected across the

various level of analysis and aligned with firm goals,

strategies, context, and characteristics”. They

suggest that strategic recruitment overlaps with four

complex disciplines: Resource-Based Theory

(RBT); Strategic Human Resources Management

(SHRM); Human Capital; and levels of analysis

(Philips and Gully, 2015). This work highlights the

need to extend the focus on recruitment from a

higher level of analysis as same as the SHRM

approach.

E-recruitment is defined as the use of the internet

to attract potential employees to an organization and

hire them. According to (Ahamed and Adams,

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment

281

2010), E-recruitment is “the practice whereby the

online technology is used particularly websites as a

means of attracting, assessing, interviewing, and

hiring personnel”. E-recruitment could be defined as

any recruiting process that an organization conducts

using Web-based tools (Kim and O’Connor, 2009).

2.1 Problem-Oriented RE

The concept of problem is central in research on

systems and software engineering (Jackson, 2001).

A problem is an undesirable situation that is

significant to and may be solvable by some agent,

although probably with difficulty (Smith, 1989). A

problem-oriented view of RE namely problem

definition refers to how problems or concerns are

represented: what problem elements should be

included, what relationships among these elements

are, and how these selections might vary over

problem types (Smith, 1989; Jackson, 2001).

Such a problem representation is created for

structuring problem domain knowledge and

orienting it towards RE in a systematic manner

(Martin and Sommerville, 2004; Kossmann and

Odeh, 2010). Hence, it offers an established problem

definition and serves as a basis for eliciting and

reasoning about requirements from different

stakeholders perspectives (Martin and Sommerville,

2004; Zachman, 2008). Given the complexity of a

real-world problem, there is no representation model

by which the various elements that constitute a

problem can be comprehensively included (Pedell et

al., 2014). Hence, each model has some advantages

and limitations.

One key example of problem representation

techniques is goal modelling (Kavakli, 2004). Goal

modelling is based on the premise that in

collaborative work situations, people are aware of

and share common goals and act towards their

fulfilment (Fouad, 2011). Hence, the problems

associated with business structure, resources,

processes, and their supporting systems that inhibit

the achievement of these goals can be defined

(Kavakli, 2004). However, a real-world problem

concerns the goals of humans which are not simple

to model for several reasons: (a) they are not known

in advance; (b) they are often abstract and imprecise

and can evolve during the life of a project; and (c)

the means that lead to goal achievement are not

known beforehand. Another example is the problem

frames (Jackson, 2001), in which frequently

occurring problem structures are identified and

related to a problem frame. This frame captures the

characteristics and relationships of the parts of the

world it is concerned with, and the concerns and

difficulties that are likely to arise. This helps to

focus on the problem space instead of moving into

the solution space. However, it is criticised being

limited in scope focusing on the objective aspects of

software problems (Hall et al., 2008).

A third problem representation technique is

Enterprise Architecture (EA). An EA, e.g. Zachman

Framework (Zachman, 2008), provides a structure

(i.e. representation) that establishes a reference of

problem definition and guides the transformation

process (i.e. methodology) towards the solution.

However, they are built on a faulty argument that a

real-world problem can be analogously represented

using the conventional architecture representations

of the manufacturing and constructions, which make

the social and subtle features often neglected or

trivialised (Pedell et al., 2014).

2.2 Representation of the Recruitment

Problem

There are a number of descriptive and prescriptive

recruitment models proposed for conceptualising

recruitment problem. The most cited ones are Rynes

and Cable’s (2003) model for future recruitment

research, Saks’s (2005) dual-stage model of the

recruitment process, and Breaugh and Starke’s

(2008) model for the organizational recruitment

process. While these models address some aspects of

recruitment problems, they are strongly solution-

oriented, focusing on what and how rather than why.

Ployhart (2006) comments on the research-practice

gap of recruitment saying “it seems organisational

decision makers do not understand staffing

(recruitment) or use it optimally”. It has been widely

suggested that a better representation of the

recruitment problem relies in the first instance on an

appreciation of its complexity (Rynes and Cable,

2003; Saks, 2005; Breaugh and Starke, 2008). This

complexity stems from a set of cognitive, social and

organisational variables involved and the nature of

their relationships (Breaugh, 2012).

This paper proposes an established

conceptualisation of recruitment problem that

describes the various problem elements and their

relationships, and shows how these problem

concepts might vary over different types of

recruitment problems. Hence, the depiction of the

constituent elements of recruitment problem and

their overlapping relationships is the essence of the

representation of recruitment problem. This

representation will help closing the gap in different

ways. It will support delaying of solution

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

282

consideration until a good understanding of the

problem space is gained. It will also provide a means

of analysing and decomposing problems into simpler

sub-problems that can be readily addressed. It will

also help stakeholders to capture and share the

necessary problem domain knowledge, and this will

be driven into the negotiation over trade-offs and

consideration of details of the solution support.

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research method used is design science.

According to (Hevner et al., 2004), design science

creates new artefacts for solving practical problems.

These artefacts can be methods, models, constructs,

frameworks, prototypes or IT systems, which are

“introduced into the world to make it different, to

make it better” (Johannesson and Perjons, 2014).

The design science research process carried out in

this research included five research activities as

defined by the design science method framework of

(Johannesson and Perjons, 2014). These activities

and their application are presented below.

3.1 Problem Explication

The first activity in the design science process is to

explicate the practical problem that motivates why

the artefacts, in our case the POCM (Problem-

Oriented Conceptual Model) and the corresponding

Onto-RPD (Ontology for Recruitment Problem

Definition, need to be designed and developed. The

practical problem is the ill-representation and

understanding of recruitment problem impedes the

realisation of the value of e-recruitment. This

problem has been faced in Secureland Army

Enlistment project which denotes a knowledge gap

in the literature. Hence, the abovementioned

artefacts are designed to solve this problem.

3.2 Requirements Definition

The second activity in the design science process is

to define the requirements of the POCM and its

detailed Onto-RPD. These requirements will be used

as a basis to evaluate the resulting artefacts and

guide the construction process of them in addition to

any refinement steps. Based on the literature review,

the following requirements are selected:

The artefact(s) should be comprehensive.

Comprehensiveness is the degree to which the

artefact(s) offers complete knowledge (Viller

and Sommerville, 2000; Fox et al., 1998).

Osada et al. (2007) refer to this as the amount

of suitable information.

The artefact(s) should be generic. Generality

is the degree to which the artefact(s) is shared

and sector/domain-independent (Fox et al.,

1998). The artefact(s) should be shared

between diverse stakeholders and activities

and not specific to a sector (Vesely, 2011).

The artefact(s) should be precise. Precision is

the degree to which the artefact(s) has correct

and accurate definitions compared to the

existing domain knowledge (Fox et al., 1998;

Osada et al., 2007).

The artefact(s) should be abstract / granular.

Abstraction or granularity is the degree to

which the artefact(s) represents a core set of

primitives that are partitionable in different

levels (Viller and Sommerville, 2000; Fox et

al., 1998; Osada et al., 2007).

The artefact(s) should be perspicacious.

Perspicacity is the degree to which the

artefact(s) is easily understood by the

practitioners so that it can be consistently

interpreted across the enterprise (Fox et al.,

1998).

3.3 Design and Development

This third activity is to design and develop the

artefacts that address the explicated problem and

fulfils the defined requirements, in this case design

and develop the POCM and Onto-RPD. The design

and development is described in section 4.

3.4 Demonstration and Evaluation

This activity is to use and assess how well the

artefacts solve the practical problem taking into

account the previously identified requirements. We

have evaluated the POCM and Onto-RPD by

conducting a focus group of experts from

heterogeneous recruitment-related domains. The

results are presented in section 5.

4 DEVELOPMENT OF POCM

AND ONTO-RPD

The POCM and Onto-RPD were developed by

means of applying Soft Systems Methodology

(SSM) (Checkland and Poulter, 2010) as an

approach upon three case studies to capture the

different problem-oriented worldviews and develop

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment

283

root problem definitions. The artefacts were not

simply developed by a matter of consolidating

partial vocabularies from the literature, but through

bottom-up analysis of data using many techniques

associated with the development of grounded theory.

First, the Secureland Army enlistment case study

(case 1) was analysed using many problem analysis

techniques (e.g. Rich Picture, CATWOE, 5 Whys,

and Cause-Effect analysis). The first version of the

POCM was developed in (Alamro et al., 2014). This

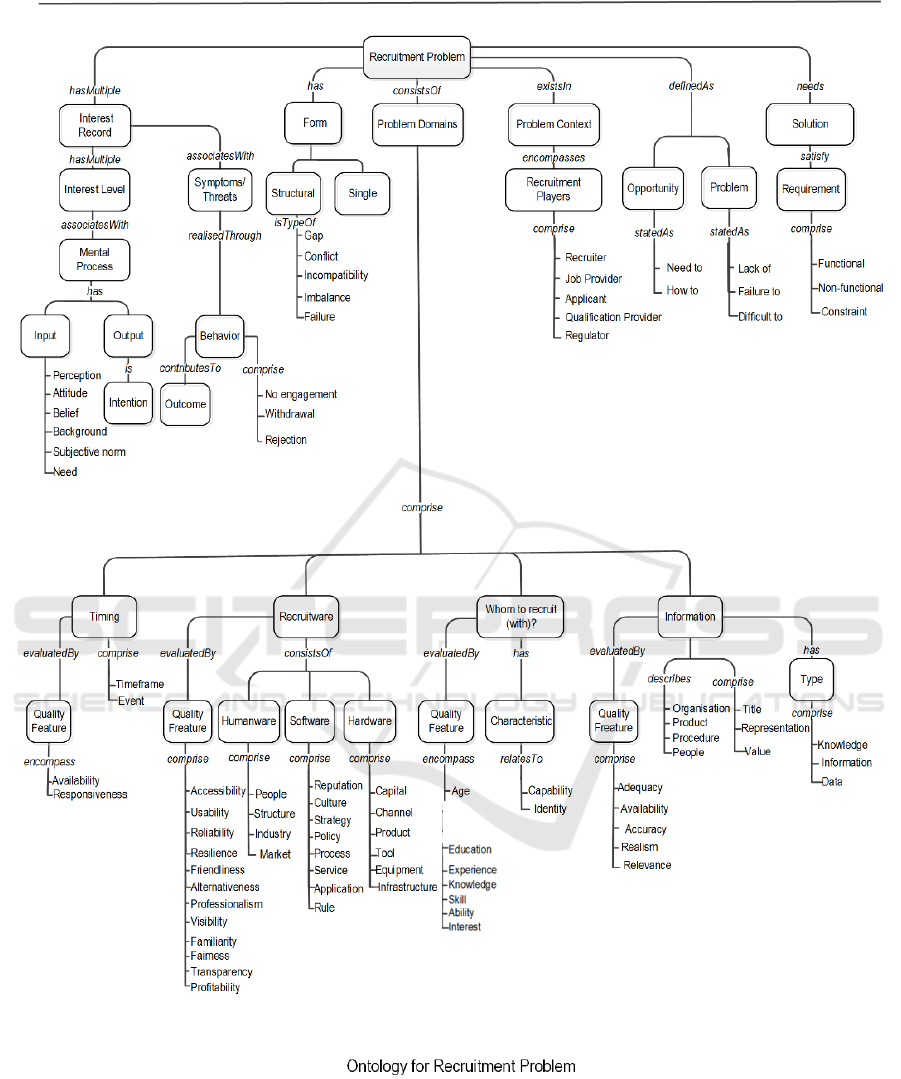

version, Figure 1, was later refined and supported by

a corresponding Onto-RPD, Figure 2, for more

elaboration using text analysis from the other case

studies: British Army Regular Enlistment (case 2)

and UK Undergraduate Universities and Colleges

Admissions Service (UCAS) (case 3) respectively.

The final POCM, Onto-RPD, root problem

definitions are described briefly below. The POCM

is illustrated in Figure 1. The problem types

extracted from the three case studies to develop the

conceptual model are explained in Table 1. Figure 2

represents the ontology of recruitment problem

definition.

5 DEMONSTRATION AND

EVALUATION OF POCM AND

ONTO-RPD

In this section, the demonstration and evaluation of

the POCM and Onto-RPD are presented.

5.1 Evaluation

The evaluation of the POCM and Onto-RPD was

carried out with a focus group consisting of 10

experts from different recruitment-related domains

(e.g. HR, marketing, psychology, and management).

These experts were academic staff and research

students from a university in the UK. As an

assignment, subjects were required to write a

description of a recruitment-related problem

situation they faced during the focus group. These

descriptions were revised with the corresponding

subjects and then circulated to others being asked to

carefully state and define the central and primary

problem in each case from their perspectives. The

answers were collected and prepared for the focus

group meeting. A package including the POCM and

Onto-RPD, a list of defined terminologies, and a

questionnaire with instructions of use were sent to

the participants prior to the meeting. The experts

were asked upon each case study to discuss the

recruitment problems, their relationships, and

mapping to the resulting concepts and sub-concepts

as incorporated into the POCM and Onto-RPD. A

questionnaire was then completed by each expert

after the discussion. Root problem definitions with

definition of key concepts are elaborated below.

Hardware. A general term that includes the

physical elements (i.e. tangible assets) used or

produced by a recruitment actor that can be seen,

touched, and controlled.

Humanware. A general term that includes all

human-related activities carried out by a recruitment

actor such as roles, responsibilities, relationships,

etc.

Information (Conveyed): Described as a

problem owned by all recruitment actors in which

their own information (including all types of

information) cause an impact on the others’ interests

assessed by a set of quality features (e.g. availability,

adequacy, relevance, etc.) taking into account all

influences of other problem domains.

Information (Received): Described as a

problem owned by all recruitment actors in which

the received information (including all types of

information) cause an impact on the other problem

domains e.g. whom to recruit, recruitware, and

timings assessed by a set of quality features (e.g.

availability, adequacy, relevance, etc.) taking into

account all influences of other problem domains.

Interest. Described as a problem owned by all

recruitment actors in which their perceptions of the

recruitware, information, and timing influence their

intentions to react assessed by a set of factors (e.g.

value/expectancy and background factors).

Offer Rejection / Withdrawal / No Engagement.

Described as problem owned by all recruitment

actors in which their behaviours influence the

outcomes.

Problem Context. The area in which a problem

exists.

Problem Domain. A way of considering or

conceptualising problem.

Recruitment. An enterprise system in which

different players interact according to their interests

to fill a job vacancy.

Recruitment Problem. A problematic situation

with a recruitment practice regarded as undesired

that needs to be defined to overcome.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

284

Figure 1: Problem-oriented conceptual model (POCM) for recruitment problem.

Recruitware. Described as a problem owned by all

recruitment actors in which their own attributes,

shaped by a number of elements (including

humanware, software, and hardware), cause an

impact on the others’ interests assessed by a set of

quality features (e.g. visibility, usability, fairness,

etc.) within the constraints of other problem

domains.

Timing. Described as a problem owned by all

recruitment actors in which their timings of events

cause an impact on the others’ interests assessed by

a set of quality features (e.g. availability and

responsiveness) taking into account all influences of

other problem domains.

Whom to Recruit (with). Described as a problem

owned by all recruitment actors in which their

decisions in regard to the optimum recruitment

partner to recruit with to fill a specific vacancy

influence/influenced by recruitware, information,

and timing taken into account the external factors

e.g. social, economic, political, technological, legal,

and environmental.

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment

285

Table 1: Mapping the types of problems from different case studies into the POCM.

Category Case 1 Case 2 Case 3

Recruitware-

Information

Paper-based

announcement restricts

availability of

information

Less visibility of armed

forces needs much

information be disclosed

Different tools with

different modes of

information delivery

Recruitware-

Whom to recruit

Job locations are remote

from local applicants.

We try to minimise the

impact of mobility on

applicants.

Improved reach of UCAS

services across social

classes

Recruitware-

Timing

Hard to build a strong

relationship in a short

time.

Loss of timely support

needed by other partners.

Possible adjustment after

exam results (Adjust

service).

Timing-

Information

Less time to explore job

opportunities.

Successive provision of

job characteristics offered

during recruitment

process.

Up-to-date information,

advice and guidance

(IAG).

Whom to recruit-

Information

High probability of being

offered undesired job

because of diversity

considerations.

Some information that

might persuade potential

recruits to enlisting is not

routinely volunteered.

Undesirable divide

between those applicants

who receive effective

advice and those who do

not.

Whom to recruit-

Timing

Extra time must be

available for remote

applicants.

Ongoing marketing

campaigns for different

categories of applicant.

Predefined deadlines for

different applicants to

apply and reply.

Information-

Interest

Only those who are well-

informed about the army

and its structure can

predict the location of job

The terms of service are

extremely confusing and

subject to many

probabilities

Clear entry requirements

Recruitware-

Interest

Conceived interest in

defending the country

needs to be met by

reliable enlisting

practices

Negative publicity from

Afghanistan and Iraq

might not persuade

potential recruits to

enlisting

Apply with 5 course

options

Timing-Interest Post-result recruitment

does not allow much time

to decide

Career appeals

progressively less as

potential recruits grow

into adulthood

Many applicants were

happy with pre-result

application (using

predicted grades)

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

286

Figure 2: The ontology of recruitment problem definition (Onto-RPD).

5.2 Key Findings from the Evaluation

The key findings from the evaluation that is centred

on the requirements and characteristics of the model

are presented in section 3.2, are as follows:

Comprehensiveness: three experts clearly

confirmed that the POCM and Onto-RPD are

complete covering the required knowledge of

recruitment domain. For instance, one expert

stated “it is impressive, I can say that your

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment

287

models (i.e. POCM and Onto-RPD) are quite

full”. In contrast, one expert stated that “the

two models in addition to the glossary shall be

used together for complete knowledge, the

POCM was little vague until I referred to the

Onto-RPD and glossary”.

Generality: six experts acknowledged that the

POCM and Onto-RPD are quite generic but

with some comments. One stated “some

specificity would be helpful especially with

selection and interview processes”. Another

stated “information domain could be clearer

with more specific attributes e.g. job

attributes”. One also argued “the goal (fill

vacancy) needs to be expanded where many

stakeholders’ goals may exist”. However,

from an enterprise perspective, we focus on

the ultimate shared goal for which all

enterprise actors shall cooperate to achieve in

order to increase labour market share. While

also defining all difficulties and constraints

that impede the achievement of this goal from

problem-oriented perspective.

Precision: most of experts agreed that the

terms used in the models were quite common

and the definitions provided are relatively

accurate. However, one expert stated “the

term of recruitware is new, it would be better

to use more common one”. However, the term

has been used in the literature and the

definition has been agreed on.

Abstraction / granularity: three experts

confirmed that the POCM is abstract and can

be applied for problem definition in different

level of analysis. One stated “I think this is the

best part of the POCM which accounts for

why the POCM has been made too generic”.

Another stated “the core elements of the

POCM can be instantiated in different abstra-

ction levels”. In contrast, some argue “the

POCM is good for management problems”.

Perspicaciousness: five experts confirmed that

the POCM and Onto-RPD were easy to

understand and promoting problem analysis.

One expert commented “many problem

scenarios have been applied which makes

clear that the POCM and Onto-RPD are very

effective in this part”. Another stated “I can

understand where the conflicts might happen”.

Moreover, one stated “The POCM and Onto-

RPD help pose questions that may have been

forgotten by a stakeholder”. Some argue that it

lacks a step-by-step method to define the

problem.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, a high-level Problem-Oriented

Conceptual Model (POCM) is proposed for

conceptualising and synthesizing various problem

concepts of the recruitment problem space. The

POCM and hence the corresponding Onto-RPD

provide a means to better understanding how

recruitment problem may emerge, develop, and

change over time. POCM also represent and reason

about possibly conflicting aspects of the recruitment

interests arising from different enterprise recruitment

entities. The future work will focus on developing a

systematic approach to transition the recruitment

problem knowledge that is embedded in the POCM

to an e-recruitment requirements specification.

REFERENCES

Ahamed, S., Adams, A., 2010. Web recruiting in

government organisations: A case study of the

Northern Kentucky / Greater Cincinnati Metropolitan

Region, Public Performance & Management.

Alamro S., Dogan H., Phalp K., 2015. Forming enterprise

recruitment pattern based on problem-oriented

conceptual model, Procedia Computer Science, 64, pp.

298-305.

Alamro S., Dogan H., Phalp K., 2014, E-military

recruitment: a conceptual model for contextualizing

the problem domain. Proceedings of the International

Conference on Information Systems Development:

Transforming Organisations and Society through

Information Systems.

Barber, A., 1998. Recruiting employees. Thousand Oaks,

Sage Publications, CA.

Bowen, D.E., Ostroff, C., 2004. Understanding HRM-firm

performance linkages: The role of the ‘strength’ of the

HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29

(2), pp. 203–221.

Bray, I., 2002. An introduction to requirements

engineering. England: Addison Wesley.

Breaugh, J. A., 2012. Employee recruitment: Current

knowledge and suggestions for future research. In N.

Schmitt (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of personnel

assessment and selection, Oxford University Press, pp.

68-87.

Breaugh, J., Starke, M., 2008. Research on employee

recruitment: so many studies, so many remaining

questions. Journal of Management, 26(3), pp.405-434.

Carless, S.A., Wintle, J., 2007. Applicant Attraction: The

role of recruiter function, work-life balance policies

and career salience. International Journal of Selection

and Assessment, 15(4), pp. 394-404.

Checkland, P., Poulter, J., 2010. Soft systems

methodology. Systems approaches to managing

change: A practical guide.

ICEIS 2018 - 20th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

288

Fouad, A., 2011. Embedding requirements within the

Model Driven Architecture. PhD Thesis, Bournemouth

University.

Fox, M., Barbuceanu, M., Gruninger, M., Lin, J., 1998. An

organization ontology for enterprise modelling. In

Prietula, M., Carley, L., Gasser, L. (Eds), Simulating

Organizations: Computational Models of Institutions

and Groups, AAAI/MIT Press, CA, pp. 131-152.

Gatewood, R., Field, H., Barrick, M., 2008. Human

resource selection. 6

th

Edition, South-Western College

Pub.

Hall, J. G., Rapanotti, L. Jackson, M.., 2008. Problem

oriented software engineering: solving the package

router control problem. IEEE Transactions on

Software Engineering, 34(2), pp. 226-241.

Hevner A., March S., Park J., 2004. Design science in

information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28 (1),

p.75-105.

Jackson, M., 2001. Problem frames: analysing and

structuring software development problems. Addison-

Wesley.

Johannesson P., Perjons E., 2014. An introduction to

design science. Springer International Publishing,

Switzerland.

Kavakli, E., 2004. Modelling organizational goals:

Analysis of current methods. ACM symposium on

Applied Computing, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Kim, S., O’Connor, J., 2009. Assessing electronic-

recruitment implementation in state governments:

Issues and challenges. Public Personnel Management,

35(1), pp. 47–66.

Kossmann, M., Odeh, M., 2010. Ontology-driven

requirements engineering a case study of OntoREM in

the aerospace context. In INCOSE Conference,

Chicago, USA.

Martin, D., Sommerville I., 2014. Patterns of cooperative

interaction: linking ethnomethodology and design.

ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction,

11(1), pp. 59–89.

Osada, A., Ozawa, D., Kaiya, H., Kaijiri, K., 2007. The

role of domain knowledge representation in

requirements elicitation, 25

th

IASTED International

Multi-Conference Software Engineering, Innsbruck,

Austria, pp. 84-92.

Pedell, S., Miller, T., Vetere, F., Sterling, L., Howard, S.,

2014. Socially-oriented requirements engineering:

software engineering meets ethnography. In V.

Dignum and F. Dignum (eds.), Perspectives on

Culture and Agent-based Simulations, Studies in the

Philosophy of Sociality 3, Springer Switzerland.

Pfieffelmann, B., Wagner, S., Libkuman, T., 2010.

Recruiting on corporate web sites: Perceptions of fit

and attraction. International Journal of Selection and

Assessment, vol. 18, pp. 40-47.

Phillips, J., Gully, S., 2015. Multilevel and strategic

recruiting where have we been, where can we go from

here. Journal of Management, 41(5), pp. 1416-1445.

Ployhart, R., 2006. Staffing in the 21

st

century: New

challenges and strategic opportunities. Journal of

Management, 32, pp. 868−897.

Randall, S., 1987. Personnel and human resource

management. 3

rd

Edition, West Pub. Co.

Ray, G., Muhanna, W., Barney, J., 2007. Competing with

IT: The role of shared IT-business understanding.

Communications of the ACM, 50(12), pp. 87–91.

Rynes, S., Cable, D., 2003. Recruitment research in the

twenty first century. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, et

al. (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and

organizational psychology, vol. 12, pp. 55–76, Wiley.

Saks, A. M., 2005. The impracticality of recruitment

research. In A. Evers, O. Smit-Voskuyl, & N.

Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of personnel selection,

Basil Blackwell, pp. 47-72.

Siegemund, K., 2014. Contributions to ontology-driven

requirements engineering, PhD Thesis, Technische

Universität Dresden.

Smaliukienė, R., Trifonovas, S., 2012. E-recruitment in

the military: challenges and opportunities for

development, Journal of Security and Sustainability

Issues, 1(4), pp. 299–307.

Smith, G., 1989. Defining managerial problems: A

Framework for Prescriptive Theorizing. Management

Science, vol. 8, pp. 963-981.

Tresch, T., 2008. Challenges in the recruitment of

professional soldiers in Europe. In: Vasile, P., Corina,

V.,George, R. (eds). Strategic Impact, Romania,

National Defence University, vol. 3, pp. 76-86.

Vesely A. Theory and methodology of best practice

research: A critical review of the current state. Central

European Journal of Public Policy, vol. 2; p. 98-117.

Viller, S., Sommerville, I., 2000. Ethnographically

informed analysis for software engineers. IJHCS,

53(1), pp. 169–196.

Zachman, J., 2008. The concise definition of the Zachman

framework, link: https://www.zachman.com/about-

the-zachman-framework.

Problem-Oriented Conceptual Model and Ontology for Enterprise e-Recruitment

289